1

Lessons in Quality Improvement*

This section includes discussions from a variety of perspectives: non-health care services, health plans, hospitals, and nursing. It was not possible, however, to include examples from all settings, such as smaller physician practice settings and long-term care settings.

NON-HEALTH CARE SERVICE SECTOR

Although improving quality requires the use of specific tools, developing these tools and putting them to use is only part of the challenge. As Scot Webster of Medtronic explained, the larger part of improvement is changing culture and driving change.

Webster offered Medtronic’s experience with quality improvement as an example. Medtronic manufactures a wide variety of medical devices, including pacemakers and insulin pumps. Every five seconds, Webster said, somewhere around the world a Medtronic device is implanted. In 2006 Medtronic’s net sales were $11.3 billion; the company spends approximately 10 percent to 15 percent of its revenue each year on research and development. The quality of its products is imperative, but as Medtronic is a high-volume company,

the efficiency of its operations and the flow of its processes are also critical factors in its success.

For these reasons Medtronic set itself the goals of assuring that it produced high-quality products while at the same time increasing efficiency and improving flow. Webster highlighted three issues that Medtronic found to be important in reaching these goals: lead time, external variability, and internal variability. Lead time is the period of time from the beginning to the end of a process. A patient who must sit in the waiting room of an emergency room for three hours is an example of a need to reduce lead time. Variability refers to differences in conditions or in how a process is performed; external variability refers to differences that cannot be controlled by the process’s operator, while internal variability refers to processes that can be. An epidemic would be an example of external variability, Webster said, while incorrect prescriptions would be an example of internal variability. If an organization can reduce lead time and internal variability, he said, it can gain the flexibility it needs to manage external variability, which in turn will lead to improved customer experiences and reduced costs. These three issues—lead time, external variability, and internal variability—are important not just in manufacturing, Webster said, but in health care as well.

There are a number of tools that can be used to improve quality and focus on the problems of lead time and variability, Webster said. In its efforts to maximize profits, Medtronic chose two: Six Sigma and Lean. In particular, Medtronic combined the two tools to create an innovative technique it called Lean Sigma. The company created Lean Sigma for three reasons, Webster said.

The first reason was that the goals of both of these tools are to decrease error and reduce waste from processes. Six Sigma focuses on the efficiency of a single process, using standard deviations as a measure to track performance. The methodology Six Sigma follows is called DMAIC, for Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, and Control. The first step is to characterize problems with products or outcomes by defining what the problems are and then finding ways to measure performance. After measuring performance, these resulting data undergo statistical analyses to identify the problem with the process. Only when the process problem is identified can the process be improved, whether through automation or perhaps by something as simple as turning off a knob. The last step of DMAIC is control, which refers to the need to sustain change so that the problem does not recur. Statistical testing and evidence are two essential components of Six Sigma, Webster noted.

Lean also follows the DMAIC methodology, Webster explained,

but its focus is on the flow of multiple processes as opposed to the efficiency of a single process. Lean is a tool for improving quality, as guided by customer demands and the desire to minimize waste, while also allowing for flexibility. A central part of Lean is the balancing of resources. In a hospital setting, for example, that could mean that when a nurse in one department has spare time, he can be retasked to help out in another area. In a factory, machines can be moved around so that the flow of parts from one machine to another may require less time. If each process in a system takes the same amount of time, Webster argued, patients would not wait unnecessarily in a hospital and inventory would not sit idle between processes in a factory. In Lean, Webster said, all inputs are measured so that customer requirements can be met with minimal wasted resources.

Webster estimated that Medtronic currently is running over 1,000 Lean Sigma projects, with some dramatic results. For example, a factory in Galway, Ireland that manufactures stents reduced its lead time from 17 hours to 1.7 hours and at the same time increased output from 500 units per shift to 800 units while using approximately the same number of employees. The factory used Lean to balance flow and production and Six Sigma to reduce variability in many of the processes.

The second reason Medtronic chose to use Lean Sigma, Webster said, is because Lean and Six Sigma complement each other well. Depending on the problem, either Lean or Six Sigma can be used, he said, and some situations will require the use of both.

The third reason Medtronic combined Lean and Six Sigma is because of their ability to form a science out of process. Analyzing processes in order to identify reasons for variability and to determine which processes statistically yield better outcomes requires that data be accumulated about those process, and through Lean Sigma, Medtronic has developed an evidence base that it uses for improvement. The DMAIC methodology and the science of Lean Sigma apply to all systems with processes, Webster said. In particular, they are not limited to the manufacturing world and would make sense to apply in health care.

But quality improvement is more than just tools, Webster said. Indeed, he estimated it to be only about 30 percent application of various tools and 70 percent working to create a culture of continual change. Once an improvement event has occurred, the operators have been equipped with the tools needed to improve, but sustaining the improvement demands that the operators incorporate quality improvement as part of their own culture. Medtronic has

experienced this transformation, as demonstrated by the thousands of employees who now focus on quality, Webster said. “You have to get it in the DNA. You have got to get it in the culture. It is not about being good at the projects. It is about having this as the way we lead.” Once quality improvement is embedded in the culture, Webster said, quality experts are no longer necessary because improvement is self-sustaining. By embedding quality improvement in its culture, Medtronic is developing its future leaders, he said.

At Medtronic, each business runs itself without a high level of corporate command, which has allowed each business to develop its own culture and its own priorities. Each business must then independently find the need to use tools such as Lean Sigma.

In offering advice to the health-care industry, Webster first cautioned that Lean Sigma should not be seen as the answer for all quality problems. There are many problems that require a “just do it” approach, for instance, smaller projects that do not require Lean Sigma. Webster suggested keeping the focus of quality improvement efforts small at first. Involvement in other operations could distract from the focus of process improvement, as the goal of improvement should not be to improve margins or technology, but to produce better outcomes. Lean Sigma should be used to support the creativity and experience of health care providers, not as a replacement.

INTEGRATED HEALTH CARE DELIVERY SYSTEM

As an integrated health care delivery system, Kaiser Permanente has a unique approach to quality improvement, said Scott Young of Kaiser’s Care Management Institute. The communities Kaiser serves and its 8.6 million members are at the center of Kaiser’s mission. Having an integrated delivery system means that Kaiser’s multi-specialty group practices, its hospitals, and its insurance are all affiliated. This allows the company to coordinate care across its members’ lives; to be accountable for the quality, cost, safety, and service of its members; to have a unified medical record that enables capabilities to measure and improve care; and to directly link coverage design and services rendered, Young said.

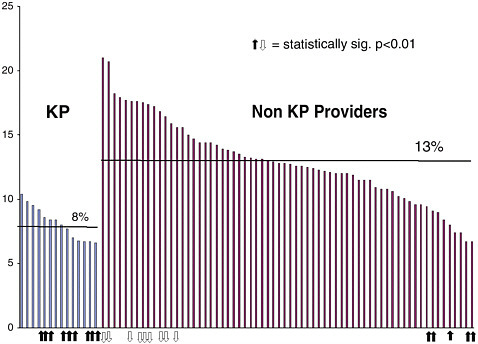

Quality is integrated into every level at Kaiser, from medical centers to the national program office, Young said. Kaiser views quality, safety, cost, and service as the four dimensions that lead to improvements in care. The quality of care received around the country is uneven, Young said, using a chart of 30-day mortality after acute heart attack (Figure 1) to demonstrate his point. The 30-day mortality of Kaiser patients averaged 8 percent, with values

FIGURE 1 Comparison of 30-day mortality rates after acute heart attack. Kaiser Permanente members have a significantly greater chance of survival from heart attacks than non-members. The study, released in February 2002, showed that the survival of heart attack patients at all Kaiser Permanente hospitals was better than the statewide average. Overall mortality was 8 percent versus the statewide average of 12 percent.

SOURCE: 2002 study by the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD).

ranging from 7 percent to 10 percent. This is in marked contrast to other providers, which had an average mortality rate of 13 percent and a much higher range.

Underlying this difference in outcomes, Young said, are uneven applications of evidence-based care, which result in unwanted variations. In particular, these variations can often be linked to missed opportunities to improve quality and—at the extreme—to safety issues, close calls, and near misses that occur every day. These safety issues and near misses can often result in poor outcomes and adverse events. These are the basis for what Young views to be the “iceberg of safety,” with increased morbidity and mortality and potential increased medical liability at the tip of the iceberg. Too often the underlying reasons for increased morbidity and mortality go unnoticed. Quality improvement programs can help prevent patient safety issues in health care.

At Kaiser, 1 percent of members are associated with approximately 30 percent of total costs, Young said. The majority of these high-cost individuals are members living with multiple chronic conditions. Service is the dimension supporting the other three dimensions of quality, safety, and cost. It is Kaiser’s belief that there is a need to make care patient-centric, to address critical needs for its communities, and to meet both member and purchaser expectations. Meeting goals in these four dimensions, Young said, is Kaiser’s key to improving the quality of care for patients.

The task of improving quality is made possible by support systems available throughout Kaiser, such as its electronic medical record system called KP HealthConnect, care management programs, KP Elder Care Network, and the use of evidence-based medicine. There are six components to the company’s approach to quality: measurement and evaluation, care management, evidence-based medicine, health information technology, innovative practice models, and team-based care.

Young noted that improvement can only be made in areas that can be measured. To evaluate its progress, Kaiser measures its performance with common metrics, such as the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS) and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), as well as tracks progress in safety, service, and efficiency. Data can be viewed nationally, by region, or by individual medical center.

Kaiser’s care management programs are focused on making the right thing to do the easy thing to do. Young described the need to use tools such as guidelines, effective and innovative care models, support teams of professionals, and technology. An important part of Kaiser’s care management programs is to provide care that is personal, effective, and efficient to members with chronic illness. An example Young used is an improvement program aimed at diabetic members and other members at risk for cardiovascular disease. Improvements were seen in those patients prescribed a specific drug regimen, including the use of aspirin, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), plus lipid-lowering drugs. The care these members received was noted in select provider panels, and the effect of the regimen was studied. Kaiser modeled the effects of the drug combination, which showed significant reductions in cardiovascular disease and lower costs. The drug regimen is currently being rolled out in all eight of Kaiser’s regions, noted Young.

Kaiser has invested heavily in its health information technology programs, which consist of an integrated electronic health record (KP

HealthConnect), kp.org (personal health record available to all members), and support tools to coordinate care for patients with ongoing and chronic illnesses. For the electronic health record alone, Kaiser will invest $4 billion. These programs have made possible more effective use of evidence, improved provider and member communication, and better support for providers in the delivery of care.

Evidence-based medicine is being embedded into KP HealthConnect to help integrate proven and effective care into the delivery systems in a real-time manner. Evidence-based medicine in this capacity exists in a variety of forms, such as clinical guidelines, preventive services, clinical libraries, outcomes reports, best practice alerts, and health maintenance reminders. These highly actionable tools are currently being integrated into clinical work streams and serve as a significant component in Kaiser’s quality improvement efforts, Young said. These implementation efforts involve providers and staff at all levels, from national guideline directors to frontline clinicians. However, gaps in the evidence base must be filled in order to produce better care, noted Young.

Team-based care has long been a fixture at Kaiser. The multi-specialty groups there strive to provide a host of physical and virtual services to best serve members’ needs. These capabilities now include email and virtual provider visits and electronic pharmacy and lab services. As health care shifts more toward the home, virtual, and self-care environments, more innovative care models will need to be developed, Young concluded.

HOSPITAL PERSPECTIVE

Craig Miller of Baptist Health Care System described how this particular hospital system changed its culture. Baptist is a four-hospital system in northern Florida and southern Alabama. In 1997, Miller said, Baptist was a place that provided poor quality care and had low employee morale, below-average physician satisfaction, and poor patient satisfaction. When the hospital leadership realized that change was necessary to improve employee satisfaction and to solve financial problems, Baptist began to focus its efforts on the people associated with the system—the patients and the employees. With this focus, Baptist transformed into a hospital system that now provides excellent quality care, as evidenced by the system winning the 2003 Baldrige Quality Award.

Baptist built its vision of change around five pillars of excellence, Miller said: people, service, quality, growth, and finance. In addition to these pillars, Baptist focused on the Baldrige criteria for excel-

lence to transform itself.1 To operationalize the changes required to achieve their vision, Baptist adopted five keys: create and maintain a great culture; select and retain great employees; commit to service excellence; continuously develop great leaders; and hardwire success with systems of accountability.

Miller said that the first key—create and maintain a great culture—is based on strong communication. This communication is enabled by involving all of Baptist’s employees in feedback, education, surveys, and employee forums. To make this meaningful and engaging, Baptist changed its culture and began in a structured manner to share stories about patients, innovations by individual providers, and patient-provider interactions.

Employees are the foundation of the organization, Miller said, and many improvements begin as innovations by employees. Therefore, Baptist’s second key to excellence is selecting and retaining great employees. Employees are given a sense of ownership over the selection process. For example, interviewees are asked questions by their potential peers during the interview process. Baptist also focused on retaining employees. Management personally recognizes those individuals who exemplify desired behaviors, and every quarter outstanding employees are acknowledged for being exceptional leaders by the company’s legends and champions program. One particular focus of this second key to excellence is engaging physicians. By making physicians a central part of the culture change, Baptist was able to improve both clinical aspects of care and employee morale. It was noted that although employee satisfaction does not necessarily result in delivery of high quality care, employee satisfaction is used as a quality indicator. Employee morale has improved tremendously and turnover has decreased, leading to cost savings at Baptist.

A commitment to service is the third key to excellence. An example Miller used here is a strategy called scripting, where employees are given scripts to follow during particular situations. By using scripting, a consistent level of service performance can be ensured, Miller said. Furthermore, hospital leaders are constantly going on rounds, making themselves available to their employees and patients so they can address problems firsthand. Apologizing for mistakes and then learning from them has become a large part of Baptist’s culture, Miller added.

The fourth key to excellence is continuous development of great leaders. Baptist puts a lot of effort into developing its leaders. “The big difference between winners and losers, whether they are organizations or individuals, is that winners understand that learning, teaching, and leading are inextricably intertwined,” Miller said, quoting Noel Tichy, director of Global Business Partnership at the University of Michigan. Baptist teaches its leaders how to learn and listen, skills that are disseminated to other employees through what Miller calls “cascade learnings.”

Hardwiring success through implementing systems of accountability is the fifth key. An important element of this is having 90 day-work plans that require action to help reach a system goal. These plans require each pillar of excellence to be addressed, establishing goals and objectives, identifying responsible individuals, and providing measurable outcomes for each. Transparency in communication and goals is critical, explained Miller.

Baptist’s focus on quality has led it to become one of Fortune’s 100 Best Companies to Work For for the sixth straight year. The quality of care provided has improved dramatically, Miller said. Its journey led it to the Baldrige National Quality Award. Its journey began by making changes within.

NURSING PERSPECTIVE

Nurses are central to improving the quality of health care delivery, said Marita Titler of the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. In her facility, the department of nursing has a quality management committee. The group has broad representation, bringing together nurses from each clinical division and from other areas of focus, such as infection control. Work groups have also been put in place that report to the quality-management committee to target specific, interdisciplinary issues, such as pain, skin care, fall prevention, and medication management.

Improvements are driven by data. Issues that data are collected on include medication errors, falls, pain indicators, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services indicators, such as discharge instructions for heart failure patients. Interdisciplinary approaches are often required to make improvements, Titler said.

The University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics bases its implementation of new processes and procedures on seven principles, Titler said. The first of these principles is that education is necessary but not sufficient in order to change practice behaviors. The second is that implementation is not necessarily sustainable; constant track-

ing and improvement is required to improve the likelihood that a change will be sustained. The third principle is to facilitate doing the right things. The fourth is that data need to be effectively transformed into useable and actionable information. The fifth principle is to have a clear focus for implementation. The sixth is coordination among all players, which is especially useful in complex interventions. And the seventh principle is to pilot or try the intervention prior to implementing the change systemwide.

Improving care requires a number of strategies that integrate these seven principles, and at the center of them is engaging the workforce, Titler said. Data are necessary for making care evidence based, and data should be collected not only for outcomes of care but also for the care processes that contribute to those outcomes. Data should be analyzed before, during, and following implementation of evidence-based practice changes to understand the impact of the improved care delivery.

Presenting data at the patient care unit or clinic level using statistical tools is helpful for nurse managers, and facilitates staff involvement in process improvements. Such tools include statistical process control charts, run charts, and Pareto charts. Other important strategies for improving care include listening to staff, presenting and discussing the evidence base for clinical practices such as fall prevention, and engaging unit-based change champions in process improvement and point-of-care coaching. The work of evidence-based practice improvement must be made visible through mechanisms such as internal newsletters, publications, and senior leadership reports. Interdisciplinary and interdepartmental collaboration are essential and the role of leaders is critical in engaging employees in change, Titler said. Leaders need to develop action plans to increase transparency, such as defining accountable persons, identifying an intervention’s effect on patient care, and making sure the plan for implementation is well understood. Without a leader’s vision and guidance, effective and well-planned practice improvements are unlikely to be sustained. Key questions for evaluating the success of quality improvement programs include: Have goals of the prior year been achieved? Are core metrics improving? Are people working collaboratively across departments and disciplines to improve patient care? Are staff seeking out quality improvement personnel for guidance? Challenges in improving quality of care, Titler said, include system issues such as using clinical documentation systems, competing demands by various external agencies, and using a mechanistic rather than a complex adaptive system approach. Improving systems and care processes is the role of all involved in health care.