1

Populations at Risk: Local to Global Concerns

NATURE OF THE PROBLEM

The South Asian earthquake and tsunami of December 2004, the Pakistan earthquake and Hurricane Katrina in the latter part of 2005, and the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Darfur graphically illustrate the human toll of natural and human-induced disasters and the ongoing need for understanding the populations at risk from such events. Each year, millions of persons are affected. The global disaster death toll in 2004 and 2005 was higher than for any two-year period in the last decade, largely attributed to two singular, regionally significant events—the Indian Ocean earthquake-tsunami and the Pakistan earthquake.

Less frequent, sudden-onset natural events that trigger humanitarian disasters capture public attention and significantly underscore such critical outcomes as deaths and economic and livelihood losses. These events also involve the mass movement of groups of people away from their homes either as refugees to other countries or within their own borders, as internally displaced persons (IDPs). However, these types of disasters may mask the equally important consequences of more frequent or chronic events, such as flooding, tropical storms, drought, famine, and civil strife. Indeed, while the total number of refugees under the mandate of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) continues to fall, the total population “of concern” to UNHCR, including refugees, IDPs, returnees, and stateless persons, has remained fairly constant during the past 10 years (UNHCR, 2006).

With both sudden-onset and chronic events, the populations under consideration require humanitarian relief at the time of, or immediately following, the crisis, as well as in the post-disaster, recovery phase of the event. Development aid ideally serves as a preventive measure to increase the resistance of a particular group of people to the effects of a natural or human-induced event, thereby decreasing their vulnerability. Development aid is also an important element of the disaster cycle with a role in generating a sustainable foundation for a population to support itself. Considerations of populations at risk, therefore, ought to address chronic and sudden-onset events at local, regional, and national scales and in the disaster relief and recovery and the development phases.

CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

In May 2004, the Humanitarian Information Unit of the U.S. Department of State hosted a Workshop on Systematic Population Estimation together with the U.S. Census Bureau and the National Academy of Sciences. The workshop facilitated discussion of approaches to population estimation in regions of the world generally lacking in data and prone to experiencing human-induced or natural humanitarian crises. The workshop resulted in recognition of the need for a more systematic U.S. government approach to subnational population estimation.

This study was an outgrowth of the information gathered at that workshop and was conducted at the request of the U.S. Department of State, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), U.S. Census Bureau, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As a response to this request, the National Research Council (NRC) established the Committee on the Effective Use of Data, Methodologies, and Technologies to Estimate Subnational Populations at Risk to address the issues outlined in the study’s statement of task (Box 1.1). The committee consisted of 12 experts from academia; international organizations; and national bureaus with expertise in geography, demography, geographic information science and remote sensing, public health, natural disasters, environment and climate, sociology, humanitarian affairs, and economics; and individuals with experience in planning and delivering humanitarian assistance following natural and human-induced disasters (Appendix A).

COMPLEXITY OF THE SITUATION

A timely response and the delivery of humanitarian assistance in a disaster situation is challenging in and of itself (IFRC, 2005, 2006). Efficient coordination of various actors involved in disaster relief requires a well-

|

BOX 1.1 Statement of Task An ad hoc committee under the auspices of the Geographical Sciences Committee will conduct a study on improving demographic data, methods, and tools and their application (1) to better identify populations at risk—groups that are susceptible to the impact of natural or human-made disasters; and (2) to improve decisions on humanitarian intervention, disaster relief, development assistance, and security for those populations at subnational scales. The study will be organized around a workshop that will address the following tasks:

|

organized, cross-institutional, inter- and intragovernmental structure that transcends the international public and private sectors. These actors include local and national governments in the affected countries, international and national nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that offer relief, and governments that donate aid directly or through third parties. Coordination involves communication between these different actors in order to donate, receive, and distribute the appropriate aid to those most in need in a timely fashion. Recognizing that coordination is a critical factor in the successful response to disasters and emergencies, much attention has been given to the coordination of international relief efforts in recent years. At the international level, the role of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) has been expanded significantly, whereas UNHCR continues to be the lead agency for refugee situations.

Relief efforts may be particularly challenging if the transportation and electrical infrastructure are not functioning as a result of the disaster or

are not of a reliable standard due to the relative poverty of the country in question; similarly, the conditions for relief workers to operate safely and effectively may also be compromised. Regardless of the conditions that relief workers and agencies encounter in disaster response situations, the underlying theme of relief efforts is to give aid to affected populations and to assist these populations in their recovery following a disaster. Data considered fundamental to relief efforts include the total number of people affected by the disaster in any specific, affected (subnational) area and the characteristics, density, and vital statistics of that population subset. Often, however, decision makers lack the requisite population or demographic data for the affected area, and the deployment of emergency response teams without even rough estimates of the number and location of the people in the vicinity of a disaster is not uncommon. Even if data on the population at risk are available, their usefulness may be hampered by the impact of the disaster or conflict or by impediments engendered by inefficient coordination among responding agencies, government(s) of the affected nations, and organizational structures in place to provide relief to the people in crisis.

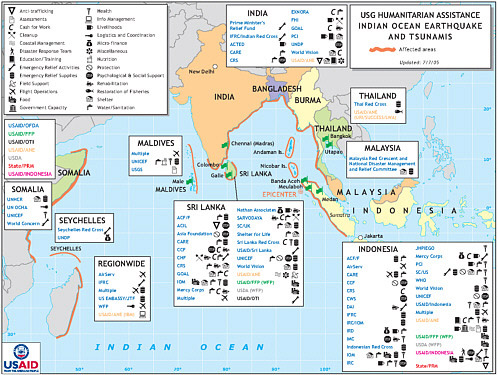

Increasingly, humanitarian relief for disasters has become international in scope, involving both international organizations and programs and country-to-country assistance. For example, the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami disaster saw assistance from dozens of NGOs and more than 50 countries not directly affected by the event (Figure 1.1). Thus, risk, vulnerability, and disaster planning and response transcend individual states and countries and point to a need for data that are global in reach in order for governments and intergovernmental programs to prepare and respond accordingly.

Decision makers need interpreted data in real time that can be visualized easily, such as those packaged in geographic information systems (GIS). Once the initial emergency period has passed, accurate data on the characteristics and size of the population are required for recovery, reconstruction, and resettlement of the displaced persons. For this succession of events to take place, information on the affected population ought to be collected and shared as soon as possible and provided to update existing national databases.

POPULATION DATA AND VULNERABILITY IN THE DISASTER AND DEVELOPMENT CONTEXT

Natural and human-induced disasters occur throughout the world but are often most felt by individuals living in impoverished communities or countries. Delivering effective emergency response and humanitarian and development aid to these populations at risk is part of the mandate for a variety of U.S. federal agencies (for example, Department of State, USAID), in-

ternational organizations (for example, World Health Organization, United Nations, World Bank, International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies), and nongovernmental organizations (for example, Veterans America [formerly Vietnam Veterans of America Foundation], CARE, Oxfam, Church World Service, and Médecins Sans Frontières). How many people, their characteristics, and where they are constitute critical information needed by agencies and organizations charged with disaster response. Inaccurate numbers and locations for populations can slow the relief effort and literally mean the difference between life and death. This report examines how these organizations might generate and receive information on where and which populations are most at risk and may be most affected by the disaster. Critical to the discussion is the ability to generate and use reliable georeferenced population data sets that allow population data to be linked directly with maps; this was a recurring theme expressed to the committee throughout this study process from a variety of crisis responders and development aid providers. Some of the basic terminology used in these discussions and applied in this report is reviewed below. Appendixes B and C contain a list of acronyms and a glossary of definitions.

This study focuses on the use of data, methodologies, and technologies to estimate populations at risk from or subjected to natural or human-induced disasters. A disaster is commonly defined as a singular, large, nonroutine event that overwhelms the local capacity to respond adequately (NRC, 2006). Natural or human-induced disasters often lead to massive displacement, creating a humanitarian crisis and triggering the need for material assistance, legal protection, and a search for durable solutions. Humanitarian response is generally organized according to sectors, such as health, shelter, sanitation, community services, and protection. Today, most population displacement occurs within national borders, creating so-called internal displacement (internally displaced persons). Refugees are victims of conflict, civil or ethnic strife, or persecution who flee across international borders and who are protected under international law.

Often, natural disasters are triggered by relatively short-lived events, but their impacts may necessitate longer periods of recovery and reconstruction (months to years) for communities to reestablish their livelihoods and to return displaced persons to their homes (Kates et al., 2006). Human-induced disasters, such as civil conflicts, are more likely to create protracted situations requiring long-term (years to decades) intervention and support before people can return. These protracted situations may constitute a complex emergency—“a humanitarian crisis in a country, region, or society where there is a total or considerable breakdown of authority resulting from internal or external conflict … which requires an international response that goes beyond the mandate or capacity of any single agency and/or the ongoing United Nations country program” (IASC, 2004). Response to com-

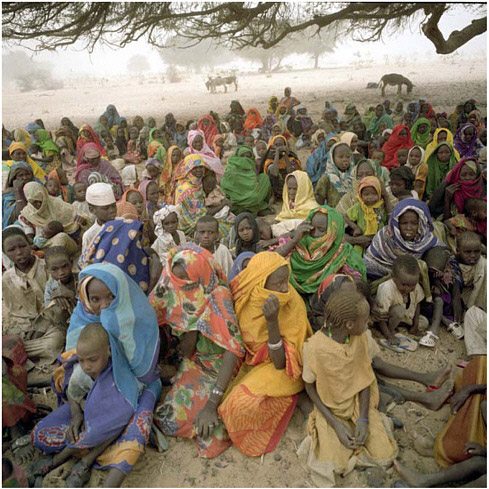

plex emergencies is often more difficult than response to natural disasters, given the potential for ongoing violence in the area, extensive loss of life, massive displacement of people, and widespread damage to livelihoods. Security risks for relief workers may slow the response further (Figure 1.2). Actors involved in all disaster relief efforts include national and local authorities, international agencies, and nongovernmental organizations. The degree of international assistance generally depends on the national capacity of the country to cope with the disaster.

A wide range of terminology is employed to describe these different types of risks, disasters, and responses. In this report, the term “disaster” is generally used to describe these different situations. Depending on the scenario, more specific terminology is used, such as natural disaster or humanitarian crisis.

The mere exposure of a population to a hazard does not create a disaster. Disasters follow from the severity or intensity of the hazard and the sensitivity and resilience of the system (population-place) exposed. This point led the expert community to enlarge the risk-hazard model to a vulnerability model (Wisner and Blaikie, 2004; Cutter, 1996), ultimately adding the environment itself to population and place in order to determine resilience (Adger et al., 2005; Turner et al., 2003) (Box 1.2).

With risk embedded in the vulnerability concept, a more vulnerable population is one that is frequently exposed to, is easily harmed by, and has low levels of recovery, buffering, and adaptation to a hazard. In this view, assessments of at-risk populations involve a linkage between population data by location (place or area), the frequency and severity of a specific kind of hazard or set of hazards acting on that location, and the resilience (coping capacity) of societal and environmental subsystems of that location.

NEEDS FOR DISASTER RESPONSE AND PREVENTION

Data

Two fundamental data needs in responding to population crises—whether disasters or complex emergencies—are where the event is occurring and how many people are likely to be affected. Inadequate spatial and temporal data of this kind during crises and emergencies significantly impair effective humanitarian response. This impediment is amplified for those countries that have poor and outdated censuses and incomplete demographic characteristics data at the local (subnational) level. While the focus on crisis response is time sensitive, data for longer-term disaster recovery, mitigation, and prevention are also important.

FIGURE 1.2 Internally displaced persons in Darfur, Birjaffa, exemplify the difficulties of responding to complex emergencies like the crisis in Darfur. Internal civil conflict and violence have led to forced movements of large numbers of the population to other areas of the country and outside the country as refugees. The mass, forced migrations of people disrupt normal agricultural growing practices, herding, and access to proper housing, clean water, sanitation, and food. Malnutrition and disease spread easily in these circumstances, and efficient supply of aid can be hampered by continuing civil conflict, heavy rainfall or drought, and continuous change in the number of people requiring assistance in a given area. Accurate counts of people and knowledge of some of their vital characteristics are important for effective and efficient delivery of needed aid. SOURCE: © Pierre Abensur, 06/04ref. sd-n-00220-19.

|

BOX 1.2 Populations at Risk and Vulnerable Populations A rich, inter- and multi-disciplinary tradition focuses on risk, hazards, and disasters (NRC, 2006; McDaniels and Small, 2004). Hazards arise from the interaction between society and natural systems (e.g., earthquakes, tsunamis, tropical storms), between society and technology (e.g., chemical accidents, nuclear power plant accidents), or within society itself (e.g., war, civil and ethnic strife, persecution, human rights violations). Hazards have the potential to harm people and places, including ecosystems. Risk, another widely used concept, is the likelihood of incurring harm—that is, the chance of injury or loss, in this case, from the hazard event. Over the last decade, the risk-hazards concept has given way to a more inclusive view of hazard and impact captured in the term “vulnerability.” Although there are numerous definitions of this concept (Wisner and Blaikie, 2004; Kasperson et al., 2005; Adger, 2006; Janssen et al., 2006), they tend to speak to the degree to which a system or unit (such as a population or a place) is likely to experience harm due to exposure to perturbations, stresses, or disturbances from natural, technological, or human-induced sources. In this case, risk is embedded in the three characteristics that comprise vulnerability:

This systemic view opens the possibility that the hazard may reside within or be strongly affected by the existing context of the exposure. The view also recognizes that both social and environmental conditions and their interactions strongly affect each of the essential elements: exposure, sensitivity, and resilience (Adger et al., 2005; Turner et al., 2003; Cutter et al., 2000). Two basic types of hazards are recognized—sudden-onset and chronic events—both of which can challenge the resilience of an exposed population. Sudden hazards tend to be “big-bang” events—earthquakes, industrial accidents, or surprise attacks—whose surprise and sheer magnitude over a very brief period overwhelm the exposed population. Persistent (or chronic) hazards, in contrast, affect the exposed population incrementally, perhaps imperceptibly at first, but they may ultimately push the resilience of the system to a tipping point and into a disaster phase. In many cases, society fails to respond to the incremental problem and thus becomes a factor in generating and accelerating the disaster. The 1930s Dust Bowl in the United States is exemplary of a chronic hazard event (Worster, 1979). An extended dry climate cycle developed over cultivation practices that were not suited for that type of climate and among a population that had minimal fiscal capacity to shift agricultural practices. Soil productivity declined, soil erosion increased, and farmers were no longer able to earn a living off the land. Ultimately, the southern Great Plains witnessed the largest out-migration of any region in U.S. history. |

Demographic Data

All disasters affect local places; and thus, the first responders to any crisis situation are the affected residents themselves. To prepare for and respond to crises adequately, subnational data on the population and its characteristics are required. Given the spatial variability in hazards, a need for spatially explicit demographic data is also evident. Typically, finer spatial resolution of data is better. For many countries, disaggregating national census data at subnational levels is difficult or impossible, even if the provision of national population censuses is possible. Haiti is a good example (see Chapter 5). Despite experiencing continuous civil strife and countless natural disasters, the first formal population census data since 1982 were released by the Haitian Institute of Statistics in May 2006 based on a national census conducted in 2003, with the support of the United Nations. In 2005, the Haitian government prepared an Emergency National Plan into which the new census data are being incorporated (H. Clavijo, personal communication, May 2006). These data, however, were not available to local or international responders during the crisis that followed the passage of Tropical Storm Jeanne over Haiti in September 2004 and added to the challenges experienced by relief workers in responding to the disaster (see also Chapter 5).

The population data needs are not only about the total number of people at risk, but also about their characteristics and the related vulnerability measures of their location. Yet, according to the UNHCR, data by gender are available for only half of the population under its mandate (11 million), while age breakdown is available for only a quarter of that population (UNHCR, 2006). UNHCR estimates that half of the population under its mandate is female, and 44 percent are under 18, yet these figures are not truly representative of the total population of concern to the organization. Ideally, finer-resolution, spatially explicit demographic data would be readily available to the disaster and relief communities. Because in many places, they are not, this committee explores alternatives.

Through extensive case studies, the vulnerability research literature has identified those factors that contribute to the vulnerability of people and the places in which they live (Bankoff et al., 2004; Birkman, 2006; Wisner and Blaikie, 2004; Pelling, 2003; Cutter et al., 2000, 2003; Heinz Center, 2002). Among these factors are health status; beliefs, customs, and social integration; racial, ethnic, and gender inequalities; wealth and poverty; access to information, knowledge, and resources; institutions; respect for human rights; good governance; and level of urbanization. Specific demographic and related variables have been identified as well, and these provide the baseline for understanding population vulnerability in both pre- and post-disaster contexts (see Box 1.3).

|

BOX 1.3 What Variables Measure Vulnerability? There are rich debates both nationally and internationally about the conceptual basis for measuring vulnerability and at what geographic scale (UNISDR, 2004). As part of the World Conference on Disaster Reduction, the Hyogo Framework of Action produced a blueprint for global disaster reduction from the local to the global (UNISDR, 2006). Despite this effort, consistent vulnerability metrics still do not exist. The United Nations Development Programme’s disaster risk index (DRI) (UNDP, 2004) and the Inter-American Development Bank’s Prevalent Vulnerability Index (PVI) (Inter-American Development Bank, 2005) have subindices that measure exposure in hazard-prone areas, socioeconomic fragility, and lack of social resilience. However, these are country-level assessments and, in the case of the DRI, focus on only a small number of hazards (earthquakes, tropical cyclones, and floods). Post-disaster field studies at the subnational level reveal that certain social, economic, and demographic characteristics influence the degree of harm to individuals or communities and their ability to recover from a hazard event or disaster. The Community Risk Assessment Toolkit developed by the ProVention Consortium (ProVention Consortium, 2006) uses a case study, mostly narrative in approach, in its community-based vulnerability assessments. However, to measure these concepts consistently across communities or at subnational levels, a set of specific variables is required. Those variables most often used are socioeconomic status (income, poverty); gender (male, female); race or ethnicity; age (number under 5, over 65); occupation and livelihood; households (size and composition); educational attainment; access to roads, rivers, airstrips; housing characteristics (owner or renter, building types); population growth; health status (mortality rates, infant mortality rates, HIV infection rates); access to medical services; social dependence (social security, welfare); and special needs populations (transients, infirmed, refugees) (Birkmann, 2006; Cutter et al., 2003; Heinz Center, 2002; Tierney et al., 2001). |

Geographic Data

Demographic data are inherently spatial; geographic data, however, are not inherently demographic. The geographic data needs in times of crises are just as important as demographic data (NRC, 2007). Disasters affect the totality of local places, so it is vital that geographic data have the requisite scale and resolution to facilitate a response. These requirements include political or administrative boundary delineations, adequate subnational maps with topographic features (rivers, lakes, mountains, coasts), land use/or land cover data, and spatial measures of existing environmental conditions. Such data could be complemented by infrastructural information (roads, waterways, airstrips, etc.) in order to deliver humanitarian assistance to the affected population. Most importantly, georeferenced data on demographic

characteristics are needed and preferably provided as anonymous individual census records so that data can be aggregated to any spatial scale. Geospatial data in emergencies can save lives by directing assistance immediately to those most in need (NRC, 2002, 2007).

In the absence of available subnational census data or population surveys to complement existing population data, proxy data can be used to match demographic characteristics to specific locations (NRC, 1998). For example, Earth observations can be used to distribute geographically the estimated daytime population from censuses to subnational levels using areal grids (Dobson et al., 2000; Harvey, 2002a,b) or census district levels (Chen, 2002). Overall estimates of population and dwelling units from satellite imagery work well at the macro level, but in areas of high population densities (e.g., cities) they may not be as reliable (Jensen and Cowen, 1999). Further, satellite measurements of nighttime lights may be used to model the distribution of the nighttime population into settlements (Sutton, 1997; Sutton et al., 2001).

Even in the presence of high-quality, fine-resolution census data, most censuses report nighttime (i.e., place of residence) population values only. The use of Earth observations from space and GIS modeling for differentiating daytime from nighttime populations (where people live versus where they work or attend school) or between residential and nonresidential populations is more difficult and somewhat experimental, but worth consideration (Sutton et al., 2003). The details of these aspects of estimating population are discussed in Chapter 2, so the emphasis here is that information about where people are (at home, at school, at work) when a disaster strikes can be of vital importance in gauging the level and directing the delivery of aid. While baseline geographic, infrastructural, and demographic information is essential for planning purposes during the first phases of the emergency, such data ought to be verified and updated at the local level as soon as possible following the disaster, particularly because any mass displacement will have rendered much of the pre-disaster information obsolete.

Operational Needs

Collection, maintenance, and use of population data will be most effective in the presence of a coordinated operational infrastructure during all phases of humanitarian relief response, recovery, and development. In the context of assisting populations at risk, during and after crises, demographic and geographic data will be most useful if their collection is timely, relative to the particular application for the data, and involves input from those groups involved in providing the requisite assistance—whether international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs), local nongovernmental

organizations, governments, or other relief and development groups. While it is challenging to quantify and analyze the degree to which individual aid and development agencies successfully function and interact either during or after the event in general, some literature has explored the factors leading to effective (or ineffective) coordination of relief, recovery, and development activities for particular disaster situations (Stephenson, 2005; Moore et al., 2003; Van Rooyen et al., 2001). Some agencies also provide public self-assessments, post-crisis, of their responses during crises (for example, UNHCR, 1998; see also Chapter 5). The challenges in providing evidence-based assessment of the “success” of an emergency response or development effort begin with defining the “success” of a relief or development operation. Perhaps more significantly, the inherent complexities of humanitarian disasters lead to difficulties in identifying one or more direct factors behind the success or lack of success of an operation. Attribution of those factors to the direct actions of one or more organizations, governments, or their operational structures proves difficult in a situation that probably involved numerous actors with various roles, interests, areas of expertise, and budgets.

The objective of this report is not to critique the actions of individual agencies or groups of agencies in responding to disasters, but rather to address the operational manner in which agencies might better collect, estimate, access, and use population data that are spatially and temporally defined and updated in the context of disaster response and recovery, as well as in development endeavors. In doing so, the committee has been guided by the premise that geographically referenced population data are a key component of relief, recovery, reconstruction, and development activities. The factors affecting the collection, analysis, and use of population data at the level of the institutions involved in responding to a crisis or its aftermath are distilled into three main categories: (1) the agency’s, organization’s, or government’s role—either as a data provider or user or as an emergency responder or development organization; (2) the capacity of the agency or organization to collect or use the data appropriately—including personnel qualifications and access to appropriate technology to collect and update the data; and (3) the agency’s or organization’s inherent administrative structure, size, and mode of operation in the aid or development situation.

These operational factors imply the need for an agency or organization to understand and implement its own role in the context of other actors. Appropriate funding for modern equipment and sustained training is also implicit in this set of factors that influence the ability to collect and use population data. The factor that is most difficult to identify and implement is the need for institutional structures that enable intra- and cross-agency or organization communication and coordination to put in place an efficient

work flow in situations that are often characterized by constant change, physical challenges, and disrupted infrastructure.

COMMITTEE PROCESS AND REPORT STRUCTURE

To address the statement of task and establish report recommendations, the committee reviewed relevant NRC reports; information submitted by external sources, including interviews, open meetings (see Appendix D), and technical papers submitted by some of the open meeting participants (Appendix E); other published reports and literature; and importantly, information from the committee’s own experience.

The committee held three open meetings in Washington, D.C., two at the National Academies’ Keck Center and one at the National Academy of Sciences Building. At its first meeting in November 2005, the committee heard from the federal sponsoring agencies and reviewed the statement of task and plans for the workshop. The second meeting consisted of a two-day workshop on the Effective Use of Data, Methodologies, and Technologies to Estimate Subnational Populations at Risk, which was held in March 2006 (Appendix D). This meeting comprised a spectrum of panelists representing practitioners, managers, and researchers in the fields of humanitarian and development aid, government, and research fields wherein demographic and geospatial information play coeval roles. Approximately half of the panel group had field experience in planning and delivering relief or development aid. Having focused some efforts to obtain access to individuals with geospatial knowledge, the committee was not surprised to hear repeatedly that access to regularly acquired, georeferenced population census and survey data was always desirable, but rarely available. Additional testimony was provided to the committee in an open session in April 2006. The final meeting of the committee was a closed session held in June 2006 at which time the recommendations were reviewed and finalized. Throughout the study process, the committee also received valuable input through informal interviews with various professionals associated with planning and delivery of humanitarian and development aid and their use and familiarity with population data to affect more efficient aid distribution.

This chapter has provided the framework and context for understanding populations at risk of disasters and humanitarian crises and the need for accurate, georeferenced data for disaster response and prevention. The chapter has emphasized the idea that population data are a fundamentally useful element of any relief or development activity, but that data alone are not enough to ensure efficient delivery of aid to those in need as the case of Hurricane Katrina shows. Chapter 2 examines the current status of techniques for estimating and analyzing at-risk populations, provides information on gaps in the coverage, and gives an overview of both contemporary methods

and proxy measures for making these population estimates. Chapter 3 is a bridge between the data issues discussed in Chapter 2 and the institutions and organizations employing the data in disaster response and development situations discussed in Chapter 4; Chapter 3 explores how demographic data are used pre- and post-event and some of the more important reasons why these data may be underutilized by decision makers during disasters. In Chapter 4, the inter- and intra-institutional challenges of data sharing and information management are described. Chapter 5 presents examples of the use of population data in response to natural and human-induced disasters in three countries—Mali, Mozambique, and Haiti—and analyzes the strengths, limitations, and possibilities for population data use and the approaches employed in situations where the existing population data were of varying quality. The real-world examples throughout the report provide lessons that can be used to improve decision making and disaster response. Each of Chapters 2 through 5 concludes with report recommendations supported by material in that particular chapter. The recommendations are collected in Chapter 6, which is a synopsis of the report’s main conclusions and recommendations for improving the capability of decision makers to identify populations at risk and, thereby, improve the effectiveness of humanitarian responses to aid these populations.

REFERENCES

Adger, W.N., 2006. Vulnerability. Global Environmental Change 16:268-281.

Adger, W.N., T.P. Hughes, C. Folke, S. Carpenter, and J. Rockström, 2005. Social-ecological resilience to coastal disasters. Science 309(5737):1036-1039.

Bankoff, G., G. Frerks, and D. Hilhorst (eds.), 2004. Mapping Vulnerability: Disasters, Development and People. Sterling: Earthscan, 236 pp.

Birkmann, J. (ed.), 2006. Measuring Vulnerability to Natural Hazards—Towards Disaster Resilient Societies. United Nations University Press, 400 pp.

Chen, K., 2002. An approach to linking remotely sensed data and areal census data. International Journal of Remote Sensing 23(1):37-48.

Cutter, S.L., 1996. Vulnerability to environmental hazards. Progress in Human Geography 20:529-539.

Cutter, S.L., J.T. Mitchell, and M.S. Scott, 2000. Revealing the vulnerability of people and places: A case study of Georgetown County, South Carolina. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90:713-737.

Cutter, S.L., B.J. Boruff, and W.L. Shirley, 2003. Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Social Science Quarterly 84(1):242-261.

Dobson, J.E., E.A. Bright, P.R. Coleman, R.C. Durfee, and B.A. Worley, 2000. LandScan: A global population database for estimating populations at risk. Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing 66(7):849-857.

Harvey, J.T., 2002a. Estimating census district populations from satellite imagery: Some approaches and limitations. International Journal of Remote Sensing 23(10):2071-2095.

Harvey, J.T., 2002b. Population estimation models based on individual TM pixels. Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing 68(11):1181-1192.

Heinz Center, 2002. Human Links to Coastal Disasters. Washington, D.C.: The H. John Heinz III Center for Science, Economics and the Environment, 156 pp.

IASC (Inter-Agency Standing Committee), 2004. Civil-Military Relationship in Complex Emergencies—An IASC Reference Paper. 57th Meeting of the IASC, Geneva, Switzerland, June 16-17. Available online at http://ochaonline.un.org/DocView.asp?DocID=1219 [accessed February 6, 2007].

IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies), 2005. World Disasters Report 2005: Focus on Information in Disasters. Bloomfield, Conn.: Kumarian Press, 251 pp.

IFRC, 2006. World Disasters Report 2006: Focus on Neglected Crises. Bloomfield, Conn: Kumarian Press, 242 pp.

Inter-American Development Bank, 2005. Indicators of Disaster Risk and Risk Management: Summary Report for World Conference on Disaster Reduction. Available online at http://idbdocs.iadb.org/wsdocs/getdocument.aspx?docnum=465922 [accessed December 2006]. http://www.iadb.org/exr/disaster/pvi.cfm?language=en&parid=4

Janssen, M.A., M.L. Schoon, W. Ke, and K. Börner, 2006. Scholarly networks on resilience, vulnerability and adaptation within the human dimensions of global environmental change. Global Environmental Change 16:240-252.

Jensen, J.R., and D.C. Cowen, 1999. Remote sensing of urban/suburban infrastructure and socio-economic attributes. Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing 65(5): 611-622.

Kasperson, J.X., R.E. Kasperson, B.L. Turner II, W. Hsieh, and A. Schiller, 2005. Vulnerability to global environmental change. In J.X. Kasperson and R.E. Kasperson (eds.). Social Contours of Risk, Vol. II. London: Earthscan, pp. 245-285.

Kates, R.W., C.E. Colten, S. Laska, and S.P. Leatherman, 2006. Reconstruction of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina: A research perspective. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 10.1073/pnas.0605726103.

McDaniels, T., and M.J. Small (eds.), 2004. Risk Analysis and Society: An Interdisciplinary Characterization of the Field. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 478 pp.

Moore, S., E. Eng, and M. Daniel, 2003. International NGOs and the role of network centrality in humanitarian aid operations: A case study of coordination during the 2000 Mozambique floods. Disasters 27(4):305-318.

NRC (National Research Council), 1998. People and Pixels—Linking Remote Sensing and Social Science. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

NRC, 2002. Down to Earth: Geographic Information for Sustainable Development in Africa. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

NRC, 2006. Facing Hazards and Disasters: Understanding Human Dimensions. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

NRC, 2007. Successful Response Starts with a Map: Improving GeoSpatial Support for Disaster Management. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

Pelling, M., 2003. The Vulnerability of Cities: Natural Disasters and Social Resilience. London: Earthscan, 256 pp.

ProVention Consortium, 2006. Community Risk Assessment Toolkit. Available online at http://www.proventionconsortium.org/?pageid=39/ [accessed October 3, 2006].

Stephenson, M., Jr., 2005. Making humanitarian relief networks more effective: Operational coordination, trust and sense making. Disasters 29(4):337-350.

Sutton, P., 1997. Modeling population density with night-time satellite imagery and GIS. Computers, Environment, and Urban Systems 21(3/4):227-244.

Sutton, P., D. Roberts, C. Elvidge, and K. Baugh, 2001. Census from heaven: An estimate of the global human population using night-time satellite imagery. International Journal of Remote Sensing 22(16):3061-3076.

Sutton, P., C. Elvidge, and T. Obremski, 2003. Building and evaluating models to estimate ambient population density. Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing 69(5): 545-553.

Tierney, K.J., M.K. Lindell, and R.W. Perry, 2001. Facing the Unexpected: Disaster Preparedness and Response in the United States. Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry Press, 318 pp.

Turner, B.L. II, R.E. Kasperson, P. Matson, J.J. McCarthy, R.W. Corell, L. Christensen, N. Eckley, J.X. Kasperson, A. Luers, M.L. Martello, C. Polsky, A. Pulsipher, and A. Schiller, 2003. Framework for vulnerability analysis in sustainability science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100:8074-8079.

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme), 2004. Reducing Disaster Risk: A Challenge for Development. Available online at http://www.undp.org/bcpr/disred/rdr.htm [accessed October 3, 2006].

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), 1998. Review of the Mali/Niger Repatriation and Reintegration Programme. Inspection and Evaluation Service. Available online at: http://www.unhcr.org/cgibin/texis/vtx/publ/opendoc.pdf?tbl= RESEARCH&id=3ae6bd488&page=publ [accessed October 4, 2006].

UNHCR, 2006. The 2005 Global Refugee Trends: Statistical overview of populations of refugees, asylum seekers, internally displaced persons, stateless persons, and other persons of concern to UNHCR. Available online at http://www.unhcr.org/statistics/ STATISTICS/4486ceb12.pdf [accessed July 5, 2006].

UNISDR (United Nations/International Strategy for Disaster Reduction), 2004. Living with Risk: A Global Review of Disaster Reduction Initiatives. New York and Geneva: United Nations, 584 pp.

UNISDR, 2006. Hyogo Framework for Action 2005-2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters. Available online at http://www.unisdr.org/eng/hfa/ hfa.htm [accessed December 2006].

Van Rooyen, M.J., S. Hansch, D. Curtis, and G. Burnham, 2001. Emerging issues and future needs in humanitarian assistance. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 16(4):216-222.

Wisner, B., and P.M. Blaikie, 2004. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disaster, 2nd edition. Oxford, United Kingdom: Routledge, 464 pp.

Worster, D., 1979. Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s. New York: Oxford University Press, 218 pp.