4

The Operational Environment and Institutional Impediments

This chapter addresses the two overlapping contexts for using data to assess populations at risk: (1) the prevention context, where the need is to develop capacity to improve response over time and enhance the resilience of local populations; and (2) the response context, where short-term needs call for data to estimate damage and provide relief. A key issue to be taken into account is the fact that fundamental differences exist between the key actors and institutions in terms of their organizational structures and the contexts within which they operate, whether in times of emergency response or in the prevention-development context. These differences can function as obstacles to effective communication and resource use during times of disaster response or planning and executing a prevention project. In a disaster or humanitarian crisis, for example, the sheer number and variety of institutional actors is potentially confusing, necessitates strong coordination mechanisms at the field level, and should include provisions for population data management. This chapter recognizes and examines the organizational differences between the various actors, some of which are inherent in their predefined roles and some of which are affected by the scale and duration of the disaster or prevention scenario. Based on these observations, the chapter concludes with several recommendations designed to assist these varied institutions and organizations in linking their domains more efficiently to collect and use georeferenced population data in disaster response and development projects.

INSTITUTIONAL MILIEU

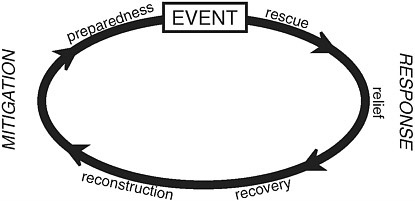

The organizational structure of international disaster response is consistent with the phases of the emergency management cycle (Figure 4.1), except that a wider array of governmental, nongovernmental, and intergovernmental entities is involved. There are many inherent dichotomies in how, when, where, and in what capacity organizations respond to disasters and humanitarian crises. First, fundamental differences exist between organizations that provide demographic data (which are usually aspatial) and those that provide spatial or geographic data (flood zones, urbanized areas), and rarely do the two work in concert to provide spatial demographic data (as noted in Chapter 2). Second, the distinction between the need for basic information technology (ability to communicate in the field and transmit data) and the equally important need for geospatial data (maps, aerial photography, geographic information systems) requires different organizational and technical approaches (Chapter 2). Finally, a dichotomy is evident between those organizations whose fundamental mission is development and those organizations whose primary concern is rescue and relief in the face of disasters and humanitarian crises. In the former, the perspective is to develop and nurture the capacity for future resilience over the long term (years to decades), while in the latter, the primary focus is immediate rescue and relief to reduce human suffering in the very short term (days to months). As might be expected, these differences reveal themselves in terms of conflicting visions and goals, the types of actors and resources involved, and organizational cultures.

As depicted schematically in Figure 4.2, while statistical and other data providers may overlap with development and response agencies, very little overlap exists between agencies engaged in development and those

FIGURE 4.1 Emergency response cycle.

FIGURE 4.2 Organization of international actors in disaster response and schematic depiction of overlapping areas of interest and activity.

engaged in response. For many years, attention has been drawn to the “gap” in post-conflict settings when humanitarian agencies are pulling out and development agencies have not yet arrived (Van Rooyen et al., 2001). Improved coordination and cooperation between these actors in post-conflict situations ought to be extended to include population and spatial data with the understanding that because the mandates of these actors are quite distinct, their data needs are likely to differ as well.

Development Organizations

Generally speaking, the primary vision of development organizations is to foster international trade, global monetary cooperation, and sustainable economic growth and practices and to reduce poverty. The vast majority of these efforts are designed to build or enhance capacity at the local level in many of the world’s less-developed regions. The provision of direct economic assistance for infrastructure, debt relief and restructuring, and assistance in reconstruction after disasters falls within the mandate of multilateral agencies such as the World Bank and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and bilateral actors such as the Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

Although highly centralized, many of the development institutions have shared the responsibility for program development between headquarters

and “in-country” personnel. While the financial assets may be controlled centrally, the available assets and infrastructure for emergency response operate at a more local level and are responsive to local needs. Development assistance organizations are also regional in scope, operating in conjunction with trade and economic alliances such as the Organization of American States (OAS).

Disaster and Humanitarian Crisis Response Agencies

Response agencies have, at the core of their missions, the desire and ability to respond to disasters or humanitarian crises anywhere in the world. This capability is in near real time, where the agency can mobilize rescue and relief resources immediately and move them into areas of need. With sudden-onset disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis, flooding, or refugee crises, relief agencies can mount a presence in the affected area within hours to days depending on the magnitude of the disaster and its location. For slower-onset humanitarian crises or ongoing pandemics (e.g., HIV/AIDS) assistance is readily available and assets are deployed when the situation worsens from a “normal” level to one that becomes critical.

Humanitarian actors include international organizations (e.g., UN High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR], UN Children’s Fund [UNICEF], World Health Organization [WHO], International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies [IFRC]), bilateral organizations (e.g., U.S. Agency for International Development [USAID], ODI), and national and local authorities and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), which can be either national or international (e.g., Save the Children, Médecins Sans Frontières [MSF], Oxfam). Some actors focus on operational activities whereas others specialize in advocacy. Most of the assistance is generally delivered by NGOs working at the grassroots level, while national authorities, assisted by the United Nations, have a coordinating function.

The role of the relief agency is to arrive with help and supplies in support of the rescue and relief operations. Once the emergency period has passed and the affected area is in a recovery phase, the services of relief agencies are generally no longer needed and they leave the area, ostensibly to prepare for the next disaster or humanitarian crisis. Relief organizations such as the IFRC, MSF, or Church World Services have both staff and resources pre-deployed and often on standby, waiting for mobilization.

Regionally based relief agencies include private-sector organizations. During the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, as a case in point (see Figure 1.1), more than 50 agencies and organizations were involved in disaster relief and recovery throughout the affected area. This aid did not include foreign direct investment from other nations (more than 50 nations

committed financially) or the millions of dollars raised by the private sector and donated to the relief efforts. The coordination and distribution of the aid created its own series of problems and issues, although amidst the grief over the scale of destruction there was also a sense of satisfaction with the overall outcome of the relief operation (UN, 2005). A longer discussion of the tsunami effort is provided in a summary discussion of the Medan Indonesia Workshop coordinated by the United Nations (UN, 2005).

Humanitarian situations of a chronic or protracted nature are often called “forgotten crises” because attention and resources tend to diminish quickly after the emergency phase of a crisis. In practice, millions of people are displaced for many years, often outside the attention of the media, with very few agencies providing assistance. Due to underfunding, such situations can escalate easily into new emergencies if, for example, food security becomes an issue and malnutrition levels rise or sanitation facilities and clean water cannot be maintained in camps or villages and lead to an increase in illness and disease.

Knowledge and Technology Institutions

A plethora of actors is involved in both disaster response and development capacity-building operations, including those who supply necessary population data. National statistical offices (NSOs) often collect, analyze, and house demographic (and other) data that are invaluable during disasters, but the extent of collaboration between NSOs and relief organizations is extremely limited. As outlined in Chapter 2, geographic information systems (GIS) and information technology (IT) are important elements in population estimation, and their use in emergency response is vital. Unfortunately, GIS have delivered less than they have promised because most uses of the tool continue to be related to the display of data rather than data analysis (Currion, 2006) (see Chapter 3).

The hindrances to integrating GIS and IT techniques in census operations are well known (Tripathi, 2001) and include continuing challenges in finding and retaining trained staff, inadequate financial resources, and inexperience with both outsourcing and inter- or intragovernmental cooperation. All of these are amplified greatly by the traditional “boom-bust” cycle of census operational funding, which inhibits the development of permanent editable census databases and the retention of staff with census-taking experience. Many of these challenges threaten the promise of technologies such as GIS, global positioning systems (GPS), mobile computing and data collection, and Internet dissemination of census results and analysis (see Chapter 3).

INSTITUTIONAL CHALLENGES

Management Vision and Complexities

Many international relief and development organizations have large bureaucracies and complex management structures. In some organizations the functions are vertically integrated or organized by sector or function, while others have horizontal structures that facilitate working across sectors. Some of the organizations have centralized staff and others have a decentralized management structure in which local offices have a large degree of autonomy at the individual country level. This allows the country office to be more responsive to the client government being served and to tailor assistance programs to the specific needs of the country. However, the decentralized management authority also adds to the complexity of disaster response capacity. An example from the World Bank (Box 4.1) illustrates some of these issues.

In view of the large number of actors or partners involved in humanitarian crises, coordination remains a critical precondition for effective response. Stephenson (2005) notes that no single agency, even those chartered to coordinate responses, enjoys a mandate to command national governments or NGOs to act in certain ways. Studies of information and communications systems in humanitarian relief NGOs found that field offices may operate autonomously from their headquarters and, potentially, from other organizations stationed in the same area; the field manager role is a critical one as the point of contact and coordination for local operations and support of an effective field team (Moore et al., 2003; Van Rooyen et

|

BOX 4.1 How Institutions Work: The World Bank In a large development organization such as the World Bank, the country office manages the response to a disaster emergency. Disaster management capacity is a small, centralized team located at headquarters. Country offices are not obliged to use the disaster management experts and in some cases may not be aware of the support available from this central capacity. Also, while a country office may have top experts in various sectors, they may not be experienced in operating in a post-disaster context, which implies time pressures, a greater need to coordinate with a large number of stakeholders, and specific tools and methods for gathering and sharing the data necessary for an effective response. If the country office does not utilize the central disaster management capacity available to it, the country team and hence, the assistance program are not informed by global experience and run the risk of “reinventing the wheel” or repeating mistakes committed in the past. |

al., 2001). A situation of concern was highlighted in the conclusions of a study of network coordination during the response to the flooding in Mozambique in 2000 wherein Moore et al. (2003) indicated that local NGOs, with ties to the local community, tended to function outside the central network of responders that included large, international NGOs. This study suggested that the influence of the international NGOs could function to foster undesired dependence of the local community on external assistance, instead of fostering self-reliance for communities to develop their own capacities to respond to future disasters. The international NGO role thus requires sensitive local management.

Working across sectors (water, food and nutrition, shelter, social services, protection, etc.) is a challenge for many large aid organizations, especially those that are structured vertically rather than horizontally. Cross-sector work requires taking a holistic view of development and making the linkages between a number of sectors or disciplines. Perhaps nowhere is this truer than in emergency response, which includes both disaster management and humanitarian assistance. Preparing for and responding to emergencies both require advanced planning on the part of aid agencies, governments, and local communities. Planning requires securing procedures, infrastructure, and agreements prior to a disaster event. The formalization of such institutional arrangements does enhance the financial and organizational capacity for effective response and recovery. Yet, oftentimes such institutional partnerships are lacking. In place of these partnerships is a set of informal, interpersonal relationships between key individuals within organizations who have worked with other key individuals in different organizations on prior projects. This informal network model transcends restrictive institutional boundaries and enables those closest to the scene to get the work done, rather than trying to work within the bounds of the formal institutional plans. While similar to the ad hoc response noted earlier, this adaptive or flexible operational environment has seen some success in disaster response (Stephenson and Schnitzer, 2006) although it does not necessarily reflect political will on the part of national-level actors.

Empowering National Statistical Offices

Although the past few years have clearly indicated the limitations of GIS in humanitarian crises, dedicated financial resources for the development of GIS databases would help ensure the timely delivery of spatially referenced population data in an emergency (Kaiser et al., 2003). This requires funding a permanent year-round or decade-round staff with dedicated field crews for updating spatial boundary files, and staffing GIS units within each agency not only with traditional cartographers but also with dedicated geographic analysts skilled in computer mapping, spatial

analysis, and database operations. These staff members would also need computers, other hardware such as scanners and plotters, and GPS units, which implies financial support from bilateral donors and international aid organizations.

Involving other national stakeholders and potential data users within a given country, ostensibly through an individual country’s national spatial data infrastructure (NSDI) effort, would help as well. An NSDI effort is marked by cooperation among national data-producing agencies, including the national mapping agency, which are empowered administratively to create and share boundary information and sometimes have geodetically corrected files that can be shared freely or for a small fee. When available, the sharing of data often does not occur because of competing bureaucratic jurisdictions or lack of recognition by the leaders of a given country. Lacking a sufficient level of support from national leaders, national statistical agencies often need either to recycle outdated maps from the previous census or to go about remapping the entire country on a tight schedule—neither of which is an acceptable option from the standpoint of accurate and up-to-date information. Far better would be the creation of a continuously maintained georeferenced database of administrative boundaries, point and line features, and locations of housing units and other structures. The use of innovative techniques (see Chapter 2) in an operational environment would help address some of the pressing needs for spatial population data (see Box 4.2), but undertaking this effort would require political will on the part of decision makers in the country and some reallocation of resources.

Elevating the NSOs to effective partners of first responders in national emergencies will require commitment, training, and reallocation of resources for this new role. The United Nations, disaster agencies, and the U.S. Census Bureau should convene a meeting of NSOs around the world to explore what this new responsibility will entail, what new training will be required to fulfill the new responsibilities, and how it could be implemented efficiently. NSOs should be encouraged to share local data with international humanitarian agencies and bilateral actors participating in the response (e.g., the U.S. Census Bureau) or with other organizations that then would share responsibility for getting the data into the field as rapidly as possible after a disaster and updating the data as the disaster and its aftermath unfold.

THE ETHOS AND CULTURE OF THE OPERATIONAL RESPONSE ENVIRONMENT

Political Challenges

The period immediately following a disaster event, particularly a sudden-onset disaster, can be extremely chaotic, with the many different

|

BOX 4.2 Spatially Enabled Demography: How We Will Estimate Populations at Risk in the Future To move forward training of the NSO staff in projecting local area census data and in digitizing the census will be needed. The largest training of NSO staff takes place at the International Programs Center (IPC) of the U.S. Census Bureau, paid for by USAID, Drylands Development Center (formerly UNDP Office to Combat Desertification and Drought [UNSO]), and other groups including national governments. This training should include both estimation and projection methodology in local areas and digitization of local maps and data. Institutions that want data available immediately after a disaster should be willing to pay for the training and data updating before the disaster since IPC operates on a strictly cost-reimbursable basis. Box 4.3 provides an overview of the structure and operations of the U.S. Census Bureau with particular focus on international operations in the context of population data acquisition, management, and training. Using hybrid analog-digital techniques would enable census practitioners to focus energies on high-priority areas such as fast-growing urban perimeters and transient populations. Mosaics of medium- and high-resolution satellite imagery could quickly and accurately locate 95 percent of the population, leaving to field crews the task of focusing on the remainder, as well as detection of errors in the field. A study conducted by UN-Habitat (Turkstra, 2006) in Hargeisa, Somaliland, explored the technical issues surrounding the use of high-resolution imagery to create a building database for tax purposes. The authors concluded that the technique represents a cost-effective and fast procedure to respond to urgent data needs in cities in developing countries and in post-conflict and disaster zones. However, decision makers need to be brought on board to endorse the efforts. |

types of actors responding to the emergency. UN agencies, humanitarian organizations (including the IFRC, large international NGOs, local groups), the military, census providers, and private-sector organizations, all have different mandates and organizational cultures, which can make sharing information difficult. Each of these organizations may have its own internal challenges to overcome in gathering and sharing data. The taxing nature of the situation is compounded further by the tensions, insecurities, and lack of mechanisms for organizations to share information with each other to produce the most accurate picture of the situation on the ground. Having said this, it is important to note that some humanitarian actors have coordination responsibilities (e.g., the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs [OCHA] for complex emergencies, UNHCR for refugee crises). Such coordination mandates should also officially include the coordination of georeferenced population data.

A major impediment is the time pressure faced by all actors—response agencies and governments alike—to produce assessment reports and relief or recovery plans based on very little information. Typically in developing

|

BOX 4.3 The U.S. Census Bureau: Mission, History, and Innovations; International Subnational Population Estimation The U.S. Census Bureau (http://www.census.gov) is the authoritative source of information on the population and economy of the United States. Part of the Commerce Department, the Census Bureau is tasked with conducting decennial population and housing censuses in years divisible by 10, and with fielding, analyzing, and disseminating results from numerous surveys and censuses on population, economy, and many other topics. Existing as a stand-alone agency for more than 100 years, the Census Bureau has a long history of scientific innovations, including:

The Census Bureau maps the territory and possessions of the United States in detail and makes its geographic products available to Congress, state legislatures (for redistricting), and the public. Its TIGER system was the progenitor of today’s Internet mapping sites such as MapQuest. The Census Bureau is also charged with providing data and analysis on countries worldwide. Existing under various names since the aftermath of World War II, the International Programs Center (IPC)—now part of the Census Bureau’s Population Division—studies foreign country populations and provides training and technical assistance to statisticians and demographers worldwide. The international technical assistance function is enshrined in the U.S. Census Bureau’s Mission Statement: The Census Bureau serves as the leading source of quality data about the nation’s people and economy. We honor privacy, protect confidentiality, share our expertise globally, and conduct our work openly. We are guided on this mission by our strong and capable workforce, our readiness to innovate, and our abiding commitment to our customers. In contrast to the domestic operations of the Census Bureau, the international programs in its Population Division are mainly externally funded by agencies such as USAID, U.S. military and intelligence agencies, and international organizations such as the United Nations. Staffed by statisticians, demographers, geographers, software programmers, and training specialists, international programs have catered to the training and technical assistance needs of more than 100 countries. Trainers and technical advisers have assisted thousands of national statistical organization professionals in survey methodology, sample and questionnaire |

|

design, census planning and publicity, cartography and GIS, and data collection, processing, analysis, and dissemination. International population estimation at the national level is conducted using published demographic data from NSOs worldwide and a variety of techniques including cohort-component and extrapolative methods. Such estimates and projections normally factor in changing birth, death, and migration rates and may be adjusted, for example, in countries with high HIV prevalence. National estimates and projections are disseminated through the International Database (http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idbnew.html). The collection of data maintained by the IPC tends to be coarser than the Census block data in the U.S. domestic collection. Another contrast with the domestic U.S. Census data is that the subnational data in the international collection are not disseminated. To acquire more finely resolved subnational population estimates, the Census Bureau assists Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s LandScan Global by supplying coarse population estimates for its ambient population data. More recently, new data sources including nighttime lights and high-resolution satellite imagery have been used with experimental methodology in a few test cases. The U.S. Census Bureau has collaborated with the U.S. Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (part of USAID), the U.S. Department of State, and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency to improve the accuracy and precision of populated place points and polygons to assist with the delivery of humanitarian relief supplies and in force protection. |

countries, poor baseline data are common at the outset and census data may also be poor or outdated (see Chapter 2). What few data are available may have been destroyed by disaster or conflict. Numerous examples of the unreliable nature of data are provided in the literature and in post-disaster agency reviews (Guha-Sapir et al., 2005; Van Rooyen et al., 2001; UNHCR, 1998). Although it is not easy to distinguish intentional overestimation of need from well-intentioned precautionary judgment based on limited data, these studies also emphasize that accurate data collection does not necessarily require more time and resources than the time and resource investment that can be saved by effective distribution of appropriate levels of aid to populations in need.

Despite the difficulties that organizations experience in obtaining access to accurate data, agencies and governments are under great pressure to produce needs assessments and reports based on scarce, perhaps unreliable data. In addition to the very real need for getting help to affected people to mitigate the impacts of a disaster, governments and the international community also have a political need to be perceived as responding quickly and generously. Governments and aid agencies should respond quickly with figures of damages and needs in order to capitalize on the fleeting global

attention that a major disaster brings and raise as much support as possible for relief and long-term recovery. For example, following the Indian Ocean tsunami, the government of Indonesia requested assistance from the World Bank to lead a damage and needs assessment mission of the affected areas of Aceh province in preparation for a donor meeting in mid-January 2005, four weeks after the event. The meeting of donors had been planned around other development issues prior to the tsunami, and the Indonesian government justifiably wanted to take advantage of this consultative opportunity to appeal for international assistance to support long-term reconstruction and recovery. However, this required undertaking a damage and needs assessment for reconstruction at a time when critical relief operations were getting under way to save lives and many communities still could not be reached due to destroyed transportation infrastructure. The existence of solid baseline data and satellite imagery to define the impact zone was critical to getting a preliminary assessment of the reconstruction needs. However, while Indonesia had complete digital maps at the lowest administrative level (Desa), inconsistent coding schemes made it difficult to link the digital maps with population census data, delaying the process of producing usable information by critical days and weeks.

Producing credible data is critical to advocating for and mobilizing international support for relief and reconstruction. While it is tempting to exaggerate figures to gain attention and garner a greater amount of support, unsubstantiated or exaggerated numbers can be discredited while accurate numbers can increase donor confidence in the missions of the organizations they support (Guha-Sapir et al., 2005; Van Rooyen et al., 2001; I. Bray, personal communication, January 2007). A study of recovery efforts following the 2000 floods in Mozambique attributed to the credibility of the damage and needs assessment document the 100 percent response rate of donors to the government’s appeal for $160 million in emergency assistance (Wiles et al., 2005).

There is also the issue of updating damage and needs assessments to capture the changing situation as more data become available. Unfortunately, damage and needs assessments are typically undertaken as “one-time” exercises that are not updated. It would be beneficial to establish mechanisms for periodic updating of assessments to ensure a better understanding of shifting needs and allow for adjustments in programming for more appropriate support.

Increased attention to monitoring needs would also allow for more meaningful consultation with affected communities to ensure that recovery programs truly reflect their needs and priorities. It is a challenge to balance the need for getting recovery programs up and running quickly against taking the necessary time to engage affected communities in the process of assessing damage and needs and designing recovery programs. However,

not taking the time to engage communities in a meaningful way can result in inappropriate and wasted efforts. For example, following the December 2004 tsunami in Aceh there was a major effort to replace lost fishing boats. A report on progress one year after the event found that while most of the need was met in terms of numbers, many boats were unsuitable in size, design, and durability. In many cases, fishermen were not consulted first, and those that were, sometimes ignored (UN, 2005). Initial damage and needs assessments, therefore, should serve as a baseline in the ongoing process of monitoring and implementation that allows for participatory planning.

In addition to the desire to increase visibility and raise as many resources as possible to assist affected communities, post-disaster and post-conflict situations engender a competitive environment in which all relief entities, including NGOs, governments, and international organizations maneuver for relief areas, opportunities, and resources. In a climate where the first responders to the scene of the disaster may attract media attention and potentially draw in new donors (Stephenson, 2005), a competitive environment may ensue among response entities and create an atmosphere of secrecy, in which players are less likely to share information, data, and resources.

Issues related to an agency’s protection of the relief area selected for concentrated attention and of the resource base are in no way limited to times of crisis. In a world of shrinking aid budgets, agencies are forced to compete for donor support, which further fuels the competitive atmosphere and does a disservice to the vulnerable populations they serve.

As the lack of willingness or ability of agencies to share data is overcome, there is also a need to improve the mechanisms for sharing data. Tools such as GPS, common formats for compiling data (e.g., the Research and Information System for Earthquakes-Pakistan; see http://www.risepak.com) and the aforementioned Humanitarian Data Model (Chapter 2) would go a long way toward equipping responders with critical information. This would help to avoid the common occurrence of communities being assessed time and time again, often without knowing why they are being assessed and what they can expect as a result in terms of aid. Government officials are also overburdened in the post-disaster phase with a steady stream of agencies demanding information on affected areas.

The Role of the Military in Disaster Response

The military has traditionally performed a vital role in disaster response, supplying the logistics and planning capacity to deal with large-scale crises both inside and outside the United States. This function shows signs of growing in the coming years (Mannion, 2006). Internationally, the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) in USAID routinely works

with military partners to ensure the delivery of supplies and information. The OFDA also houses experts from specific areas seconded from other offices. Different operations within government, both civilian and military, require the same kinds of information.

For large-scale mapping of population distribution worldwide, the U.S. Census Bureau contracted with the military for the purposes of logistical planning and ensuring compliance with Geneva Conventions regarding targeting civilian populations. The P-95 program began in the mid-1950s to delineate on a subnational scale the approximate locations of all population centers of 25,000 or greater. The rationale for the involvement of a civilian agency in this activity was that the U.S. Census Bureau housed demographic and geographic expertise not found elsewhere and provided the neutrality needed for detailed distribution of the population (U.S. Department of Defense, 1980). Such methodology, if updated and applied using new data sources, including remote sensing, GPS, and digital boundary and attribute data, could serve as a valuable resource for response efforts worldwide.

With increasing involvement of the military in civil affairs and disaster response in general, the firewall that has existed between civilian and military applications is eroding. This could potentially be a threat to the sense of trust that exists among statistical organizations, especially the bonds that have developed between the international training and technical assistance components of the U.S. Census Bureau and the countless NSOs that rely on assistance from the U.S. government. Involvement of the military and intelligence communities in demographic and geographic analysis has a long tradition; however, the relationship has maintained safeguards to ensure that sensitive or confidential information from censuses and surveys does not pass outside the civilian organization. It is essential that this firewall continue if the sense of trust among statistical organizations is to be maintained.

SUMMARY

A number of conclusions can be drawn from this chapter. First, data needs, operational plans, and response coordination are different depending on the phase of the disaster. In particular, information to enhance preparedness has often been neglected. Second, in general, while institutional actors compete for resources, coordination mechanisms exist and should be respected and enhanced. Third, no single coordinating entity exists in practice. As a consequence, a cacophony of voices and approaches can occur in the disaster response and can lead to a gap between the response and recovery phases of a humanitarian aid operation. Finally, much more could be done to integrate NSOs in all phases of preparedness and response.

Overall the problem can be distilled to a lack of leadership and a lack of awareness that information ought to be shared.

Every community needs accurate, place-specific population and population attribute data for improved disaster planning and response. The most critical data are total population and age-specific counts at the finest geographic scale possible. The level of geography (spatial resolution) is essential as well. While it may be impractical to get individual household data, aggregate counts by census tract or small enumeration area are key to effective disaster management. Equally important is the ability to aggregate these enumeration units into other geographies or spatial units, such as physical zones (e.g., coastal areas, steep slopes, floodplains) or social zones (e.g., urban areas). The enumeration unit must be georeferenced and provided in digital (polygon) form with hard-copy maps available for field responders. The georeferenced total population and age- and genderspecific counts are the minimum data sets required for disaster response. Population attribute data such as race or ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, and education are important as well and will improve the effectiveness of the response. It goes without saying that all data should be as accurate as possible and consistent with standard estimation methods and their statistical confidence.

Although the use of geographic information systems in humanitarian crises is still in its infancy, cases in which it has been used clearly demonstrate its benefits. NSOs need to commit financial resources to the development of GIS databases to ensure the timely delivery of spatially referenced population data in an emergency. This requires funding a permanent staff with field updating and spatial analysis capabilities, along with the necessary hardware and software, using resources from bilateral donors and the United Nations.

National stakeholders and potential data users within each country should be involved in national spatial data infrastructure efforts, in order to create and share boundary and attribute information. Creating a continuously maintained georeferenced database of administrative boundaries, point and line features, and locations of housing units and other structures would assist in humanitarian response efforts, but undertaking this will require political will on the part of decision makers in the country and reallocation of resources as well.

In its responses to humanitarian disasters worldwide, the U.S. government must command the efforts of many bureaus and agencies with different areas of expertise. However, for both population data and analysis, no single resource exists upon which the response community can rely for estimating populations at risk and populations affected by disasters. The U.S. Census Bureau has the international demographic and geographic

expertise to be the collaborator of first resort at the time of disaster. To perform this function, however, it needs adequate resources to permit it to organize itself bilaterally with other country governments and with the United Nations and humanitarian NGOs to develop capacity to estimate populations at risk.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the preceding discussion, the committee makes the following recommendations:

-

National and international disaster response and humanitarian agencies and organizations should elevate the importance of demographic and specifically spatial demographic training for staff members. Further, census staff and others working in NSOs throughout the world should be encouraged to undertake such training in order to promote the analysis and use of subnational data before, during, and after emergency response situations. [Report Recommendation 3]

-

Relief agencies should broaden their collaborative relationships with NSOs to ensure the acquisition of real- and near-real-time data that complement and are compatible with existing data used for disaster response. [Report Recommendation 7]

-

The U.S. Census Bureau should be given greater responsibility for understanding populations at risk and should be funded to do so. These responsibilities could include greater capacity and authority for training international demographic professionals in the tools and methods described in this report, and providing data and analytical capabilities to support the U.S. government in international disaster response and humanitarian assistance activities. The U.S. Census Bureau should also have an active research program in using and developing these tools and methods, including remotely sensed imagery and field surveys. Existing research support models that involve government-academic-private consortia could be explored to develop a framework for the U.S. Census Bureau to adopt these added responsibilities. [Report Recommendation 10]

REFERENCES

Currion, P., 2006. A little learning is a dangerous thing: Five years of information management for humanitarian operations. Humanitarian Exchange 33(March):37-39.

Guha-Sapir, D., 2005. Sensational numbers do not help the Darfur case. Financial Times, May 7.

Guha-Sapir, D., W.G. van Panhuls, O. Degomme, and V. Teran, 2005. Civil conflicts in four African countries: Five-year review of trends in nutrition and mortality. Epidemiological Reviews 27:67-77.

Kaiser, R., P.B. Speigel, A.K. Henderson, and M.L. Gerber, 2003. The application of geographic information systems and global positioning systems in humanitarian emergencies: Lessons learned, programme implications and future research. Disasters 27(2):127-140.

Mannion, J., 2006. Military to Plan for Larger Role in Disaster Relief. Available online at http://www.terradaily.com/reports/Military_To_Plan_For_Larger_Role_In_Disaster_Relief.html [accessed March 14, 2007].

Moore, S., E. Eng, and M. Daniel, 2003. International NGOs and the role of network centrality in humanitarian aid operations: A case study of coordination during the 2000 Mozambique floods. Disasters 27(4):305-318.

Stephenson, M., Jr., 2005. Making humanitarian relief networks more effective: Operational coordination, trust and sense making. Disasters 29(4):337-350.

Stephenson, M., Jr., and M.H., Schnitzer, 2006. Interorganizational trust, boundary spanning, and humanitarian relief coordination. Non-Profit Management and Leadership 17(2):211-233.

Tripathi, R., 2001. UN Statistics Division—Symposium on Population and Housing Censuses. (Issue Papers) No. 5. Identifying and resolving problems of census mapping. Mapping for the 2000 round of censuses: Issues and possible solutions. ESA/STAT/AC.84/11. July 13, 2001. Available online at http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/meetings/egm/Symposium2001/docs/symposium _08.htm [accessed December 4, 2006].

Turkstra, J. 2006. Better Information for Better Cities: the Case of Hargeisa, a Somali City. Interim Technical Report, May. UN Habitat.

UN (United Nations), 2005. Report and Summary of Main Conclusions. Regional Workshop on Lessons Learned and Best Practices in the Response to the Indian Ocean Tsunami, Medan, Indonesia, June 13-14, 2005. Available online at http://www.reliefweb.int/library/documents/2005/ocha-tsunami-05jul.pdf [accessed February 6, 2007].

UNHCR (United Nations High Commission for Refugees), 1998. Review of the Mali/Niger Repatriation and Reintegration Programme. Inspection and Evaluation Service. Available online at http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/publ/opendoc.pdf?tbl=RESEARCH&id=3ae6bd488&page=publ [accessed October 4, 2006].

U.S. Department of Defense, 1980. The Preparation of Urban (P-95) and Rural (Cell) Data; CCTC Population Data Methodology. Command and Control Technical Center, Technical Memorandum TM 16-90.

Van Rooyen, M. J., S. Hansch, D. Curtis, and G. Burnham, 2001. Emerging issues and future needs in humanitarian assistance. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 16(4):216-222.

Wiles, P., K. Selvester, and L. Fidalgo, 2005. Learning Lessons from Disaster Recovery: The Case of Mozambique. Disaster Risk Management Working Paper Series No. 12, World Bank.