10

Organization and Support of Disability Research

Previous chapters have discussed the scope and magnitude of the issues related to disability that are facing U.S. society. These issues present broad and costly challenges, but delays in tackling them will only exacerbate the challenges and increase the costs of action in the future. Although many steps suggested earlier can be taken on the basis of current knowledge or the analysis of existing data, further research on disability can help refine policies and practices and assess their relative costs and benefits. Research is also needed to generate new and more effective policies and practices based on a better understanding of the nature of disability; the factors that contribute to its creation or reversal over time; and the clinical, environmental, and other actions and interventions that can prevent or mitigate impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions.

Consistent with the charge to the Institute of Medicine (IOM), preceding chapters have proposed directions for research and conceptual clarification in several specific areas. Reflecting the complex, dynamic, and diverse nature of disability, the proposed research involves a wide range of clinical, health services, engineering, epidemiological, behavioral, and

environmental questions. In this chapter, the first section reviews the federal government’s major disability research programs and describes some developments related to these programs in the decade since publication of the IOM report Enabling America (IOM, 1997). The second section discusses a number of current and future challenges of organizing and conducting disability research. The last two sections present recommendations and concluding comments.

Unfortunately, although the committee’s review suggests that progress has been made since publication of the 1997 report, many of the same problems of limited visibility and poor coordination continue to characterize the organization and funding of federal disability research. The enterprise is still substantially underfunded, given the individual and population impact of disability in America, which will grow as the population of those most at risk of disability increases substantially in the next 30 years.

For purposes of this discussion, disability-related research is construed quite broadly to encompass research with the ultimate goals of restoring functioning, maintaining health and preventing secondary conditions, and understanding the factors that contribute to impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions.1 This research takes many forms, including classical clinical trials, observational and epidemiological studies, engineering research, health services research, survey research on many topics, other kinds of social science and behavioral studies, the development of measures and research tools, and research training and other capacity-building activities. Investment in each of these areas is important to guide clinicians, public agencies, private organizations, families, and individuals with disabilities in making and implementing choices that promote independence, productivity, and community participation.

|

1 |

The 1997 IOM report focused more specifically on rehabilitation research. It defined rehabilitation science as “the study of movement among states [that is, pathology, impairment, functional limitation, and disability] in the enabling-disabling process” (emphasis added) (IOM, 1997, p. 25). Such research involves “fundamental, basic, and applied aspects of the health sciences, social sciences, and engineering as they relate to (1) the restoration of functional capacity in a person and (2) the interaction of that person with the surrounding environment” (p. 25). The report defined rehabilitation engineering research as involving “devices or technologies applicable to one of the rehabilitation states” (p. 249). Disability research, as it is used in the 1997 IOM report, focused on the interaction between individual characteristics and environmental factors that influence whether a potentially disabling condition or impairment actually limits an individual’s participation in society. Consistent with the discussion in Chapter 2, this report uses “disability research” as an umbrella term for research related to impairment, activity limitations, and participation restrictions. It includes but is not limited to rehabilitation and rehabilitation engineering research. |

FEDERAL DISABILITY RESEARCH PROGRAMS

Developing a comprehensive and detailed picture of the changes in federally supported disability research that have occurred in the past decade is not an easy task. No agency within the federal government maintains a government-wide database on federally supported or federally conducted disability research (i.e., research that has been completed, that is in progress, or that is planned) or its funding. The committee could not identify any government-wide definition or categorization of the domain of disability research and could not always get information about the definitions of disability research that specific federal agencies use. The issue of defining and categorizing disability research is considered in the Recommendations section of this chapter.

One consequence of the broad scope and dispersed conduct of federal research and the lack of a database on federal research activities is that the committee often found it difficult to determine whether projects that might help answer some of the questions that it identified in other chapters of this report were under way. For example, research on sensory-related assistive technologies or environmental factors might be funded by units within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), the National Science Foundation (NSF), the U.S. Department of Education, the U.S. Department of Transportation, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), or the U.S. Department of Defense—and by other agencies as well.

Box 10-1 lists the three major federal agencies that have disability research as their primary missions: the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR), the National Center for Medical and Rehabilitation Research (NCMRR), and Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service (VA RR&D). It also lists several other agencies with broader research missions that include disability research. In the latter category are several units of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), in addition to NCMRR, that fund primarily biological and clinical research related to a wide range of health conditions that contribute to disability.

Overall, since the publication of the 1997 IOM report, the basic organization of federal disability and rehabilitation research appears to have remained largely the same. Funding levels for research have increased modestly in some agencies but are still inadequate to the need. Little has changed with respect to two of the 1997 report’s major critiques: the limited visibility that disability research programs have within their respective parent agencies in the federal government and the lack of coordination to set and assess the implementation of broad priorities for the productive use of limited research resources. The Recommendations section of this chapter returns to these concerns.

|

BOX 10-1 Federal Sponsors of Disability Research Major Disability-Focused Sponsors of Research

Selected Other Sponsors of Disability Research

|

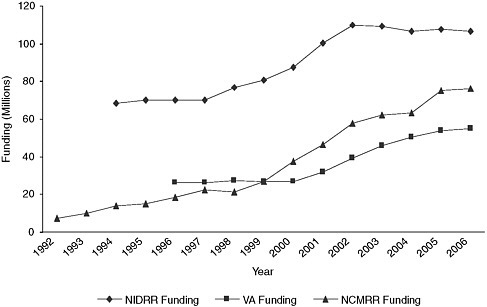

Figure 10-1 shows the funding trends for the three largest disability-focused research units in the federal government. The increase in funding during the late 1990s and early 2000s is encouraging, but the more recent leveling off of funding (except for a recent upturn for NCMRR) means that past gains will soon be dissipated by inflation.

FIGURE 10-1 Funding trends for NIDRR, NCMRR, and VA RR&D. The data are in real, not constant, dollars. The data for NCMRR do not include costs for grant administration and review, which are borne by its parent agency, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, or by the NIH Center for Scientific Review (Michael Weinrich, Director, NCMRR, personal communication, September 8, 2006). The data for VA RR&D are for direct costs only. About 20 percent of NIDRR’s budget is spent on knowledge translation and dissemination, capacity building, interagency activities, grant review, and other nonresearch purposes (Arthur Sherwood, Science and Technology Advisor, NIDRR, personal communication, September 5, 2006). The data for VA do not include rehabilitation research conducted elsewhere in the department.

SOURCES: for NCMRR through 2005, NCMRR, 2006; for NCMRR in 2006, Michael Weinrich, Director, NCMRR, personal communication, December 15, 2006; for NIDRR, Robert Jaeger, Executive Secretary, Interagency Committee on Disability Research, personal communication, February 27, 2006 (and confirmed by other NIDRR staff); for VA RR&D, Patricia Dorn, Deputy Directory, VA Rehabilitation Research and Development Service, personal communication, December 21, 2006.

Status of Federal Disability Research Efforts

National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research

NIDRR stands out among federal research agencies for its focus on research that addresses the activity and participation dimensions of disability and health. As directed by the U.S. Congress, NIDRR administers

research and related activities “to maximize the inclusion and social integration, employment, and independent living of individuals of all ages with disabilities,” with an emphasis on people with serious disabilities (NIDRR, 2006, p. 8168).2 The latest 5-year plan for fiscal years 2005 to 2009 (NIDRR, 2006) lists the emphases or major domains of the agency’s research program as

-

employment,

-

participation and community living,

-

health and function,

-

technology for access and function, and

-

disability demographics.

To build research capacity and innovation, NIDRR supports investigator-initiated projects, fellowships, rehabilitation research training, and small business projects. Beyond supporting research, the Congress also directed NIDRR to disseminate the knowledge generated by the research and provide practical information to professionals, consumers, and others; to promote technology transfer; and to increase opportunities for researchers with disabilities.3

After a period of budget stagnation in the mid-1990s, the agency saw moderate funding increases between 1998 and 2002, followed by slight reductions in funding in more recent years (Figure 10-1). This recent trend is particularly troubling because NIDRR is the primary base of federal support for research related to activity and participation. Again, taking inflation into account, even stable funding means an effective decrease in resources.

For the years from 1997 to 2004, approximately 80 percent of NIDRR funding supported research and research capacity building. Of this amount, approximately 92 percent was allocated for research, exclusive of training support (NIDRR, 2005). Approximately 19 percent supported model systems of care that are, to various degrees, involved in treatment-related research. More than 60 percent of the research spending was allocated to centers through the request for applications (RFA) mechanism. One char-

acteristic of the RFA strategy is that it helps develop over time knowledge in defined areas that reflect agency rather than investigator priorities.4

In 2006, NIDRR funded 27 Rehabilitation Research and Training Centers and 21 Rehabilitation Engineering Research Centers (Arthur Sherwood, Science and Technology Advisor, NIDRR, personal communication, March 19, 2007; see also NARIC [2006b,c]). (A few additional centers were operating on no-cost extensions of earlier awards.) These centers undertake projects in areas identified by the agency, such as community living, employment outcomes, universal design, disability statistics, personal assistance services, children’s mental health, rural communities, accessible medical instrumentation, cognitive technologies, wheeled mobility, and workplace accommodations. Some centers focus on specific health conditions, for example, multiple sclerosis and substance abuse. In addition to the centers, NIDRR supports 14 model programs for spinal cord injuries, 16 model programs for traumatic brain injuries, and 4 model programs for burns.

NIDRR engages in a small amount of collaborative research with other federal agencies. It has worked with the U.S. Department of Labor on employment research and has collaborated on various studies with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NIH, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and other components of DHHS. The amount of research funded through interagency agreements that transfer resources to or from NIDRR in support of these projects was approximately $3.8 million in fiscal year (FY) 2005 (Arthur Sherwood, Science and Technology Advisor, NIDRR, personal communication, September 5, 2006).

After acknowledging NIDRR’s unique focus on the interaction of the person and the environment as a strength of the agency, the 1997 IOM report on disability cited criticisms from past agency directors and staff and from the General Accounting Office (GAO; now the Government Accountability Office) related to agency operations. These criticisms focused

on poorly developed peer-review processes, insufficient personnel, and lack of authority. (Criticisms related to the coordinating role of Interagency Committee on Disability Research [ICDR], which NIDRR staffs, are discussed below.)

The GAO report (1989) attributed many of the agency’s problems to the policies and infrastructure of the parent department, the U.S. Department of Education. The IOM report stated that the U.S. Department of Education neglected NIDRR. With respect to review procedures specifically, the report noted criticisms that the review panels were too small, reviewed field initiated research only once a year, occasionally did not get grant applications in advance of meetings, and generally lacked the continuity of standing review panels or study sections.

The 1997 IOM report recommended that NIDRR be moved from the U.S. Department of Education to DHHS to serve as the foundation for the creation of a new agency, the Agency on Disability and Rehabilitation Research. It argued that the research activity would have a more nurturing environment at DHHS and that the move would make disability and rehabilitation research more visible and would also allow the better coordination of research activities. The recommendations section of this chapter revisits the proposal to relocate NIDRR.

Since publication of the 1997 report, NIDRR and the U.S. Department of Education have taken important steps to improve the agency’s peer-review processes, and additional planned changes are described in the agency’s current long-range plan (NIDRR, 2006a). NIDRR has created standing review panels for field-initiated proposals and the Small Business Innovation Research Program (SBIR) but not for the centers grants. Given the pattern of 5-year funding for centers-based grants and the large numbers of applicants for those grants, standing panels for that program may not be feasible because it would be difficult to predict which members of a standing committee would be from institutions that would not be applying for grants.

As part of its long-range plan, the agency “envisions a standardized peer review process across NIDRR’s research portfolio, with standing panels servicing many program funding mechanisms” (NIDRR, 2006a, p. 8178). The stated objective is to create a more consistent, higher-quality process that will, in turn, encourage the submission of stronger proposals with respect both to their substance and to their methodological rigor. In addition, the agency is implementing a fixed schedule for grant competitions that is intended to make it easier to recruit, train, use, and maintain review panel members. One stated objective of the panels continues to be the involvement of people with disabilities on the panels.

The committee believes that some additional measures could further strengthen the review process and help with capacity development. These

would include explicit consideration of the past performance of those submitting proposals in the evaluation criteria for new applications; the creation of a mechanism to allow revision and resubmission for investigator-initiated proposals; the assignment of proposal scores based on the quality of the entire proposal, similar to the approaches taken by NIH and NSF; limiting reviews by the lay consumer members of review panels to the non-technical aspects of proposals; and providing more educational feedback on the reviews, especially for young or first-time investigators. The committee understands the funding constraints and legislatively specified funding directives that influence NIDRR’s priorities, but it nonetheless believes that a larger field-initiated research program with possibly two review cycles per year might help develop new and younger researchers and open up new areas of research.

National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research

In 1990, the same year that it passed the Americans with Disabilities Act, the U.S. Congress created NCMRR as a unit within the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) at NIH. The legislation that created NCMRR also created an Advisory Council and a Medical Rehabilitation Coordinating Committee, which includes representatives from 12 other units within NIH. Although the U.S. Congress has established freestanding NIH centers, the legislative creation of a center within an NIH institute was unusual (Verville and DeLisa, 2003).

NCMRR describes its mission as supporting the “development of scientific knowledge needed to enhance the health, productivity, independence, and quality of life of persons with disabilities” through research focused on the “functioning of people with disabilities in daily life” (NCMRR, 2006, p. 2). Early in its existence, NCMRR established seven priority areas for research or the support of research (NIH, 1993). These areas, which still apply, are

-

improving functional mobility;

-

promoting behavioral adaptation to functional losses;

-

assessing the efficacy and outcomes of medical rehabilitation therapies and practices;

-

developing improved assistive technology;

-

understanding whole-body-system responses to physical impairments and functional changes;

-

developing more precise methods of measuring impairments, disabilities, and societal and functional limitations; and

-

training research scientists in the field of rehabilitation.

NCMRR administers programs in five areas: traumatic brain injury and stroke rehabilitation, biological science and career development, behavioral sciences and rehabilitation engineering technologies, spinal cord and musculoskeletal disorders and assistive devices, and pediatric critical care and rehabilitation.5 After comments about the important but seemingly peripheral relationship of the pediatric critical care research to the center’s research portfolio (NCMRR, 2002), the center pointed to the need for collaboration between pediatric critical care and pediatric rehabilitation because many critical care patients are children with disabilities.6

Recently, NCMRR defined the areas in which it saw the greatest opportunities for research in the next 5 years, given a more constrained future funding environment (NCMRR, 2006). For investigator-initiated research, the emphases are (1) translation research (from the laboratory bench to the community), (2) basic research to advance rehabilitation, (3) plasticity and adaptation of tissue in response to activities and the environment, and (4) the reintegration of people with disabilities into the community. It also defined what it described as cross-cutting objectives: developing mechanisms to support new investigators, enhancing consumer input and outreach, and extending the interdisciplinary model from basic research through applied research and community studies.

NCMRR has funded specific programs intended to develop technical expertise and infrastructure for rehabilitation research. Among other things, these programs are intended to attract basic scientists into the rehabilitation arena and promote greater communication between basic scientists and those studying applied rehabilitation topics. It will be important to gauge the impact of efforts such as these on the progress of rehabilitation research development.

Because NCMRR is not an independent center and does not have its own appropriation separate from NICHD, the amount of funding that is devoted to rehabilitation research primarily depends on how rehabilitation research proposals are scored in relation to proposals on other topics of interest to NICHD (e.g., prematurity and reproductive health). As shown

earlier in Figure 10-1, funding for NCMRR was very limited during its first few years of existence, amounting to less than $15 million in FY 1995. From FY 1999 through FY 2003, when the U.S. Congress doubled the budget of NIH overall, NCMRR funding more than doubled—from $26.8 million in FY 1999 to $62.5 million in FY 2003 (NCMRR, 2006). NCMRR saw a subsequent increase in funding to $75.4 million in FY 2005, but for FY 2006 the figure was almost the same, at $76.1 million. The funding trajectory for NCMRR before 2003 was encouraging, but the shift to essentially flat or slightly decreasing spending for NIH will mean a loss of the momentum achieved in earlier years.7 To put NCMRR’s program in context, the total FY 2005 NIH budget for research and development was almost $28 billion (AAAS, 2006c).

For FY 2004, about 65 percent of NCMRR’s total research and training budget was allocated to investigator-initiated research of various kinds (NCMRR, 2006). The remainder was devoted to training, career development, methods development, and other capacity-building activities. Among the priority areas for research, the largest shares of funding for the period from FY 2001 to FY 2005 went to assessing the efficacy and outcomes of rehabilitation therapies (22 percent) and developing improved assistive devices (17 percent). Thirty-five percent of the NCMRR research funding involved mobility limitations, 18 percent involved cognitive limitations, 18 percent involved bowel and bladder conditions, and 11 percent supported participation research or health services research.

The priorities and portfolios of NCMRR and NIDRR overlap in several areas. For example, both have made significant investments in medical rehabilitation research on spinal cord injuries and traumatic brain injuries, with minimal attempts to coordinate their activities, as described below.

The 1997 IOM report on disability observed that NCMRR’s medical orientation—a function of its organizational home in NIH—is perceived to be a strength by some but is perceived to be a potential weakness by those who contend that the medical theory of disability “frequently loses sight of the person” (IOM, 1997, p. 254). The report concluded that NCMRR—like NIDRR—suffered from its parent agency’s (in this case, NIH) inattention to disability research. One consequence of its organizational location within an institute of NIH is a limited ability to plan and set spending priorities strategically. For example, research proposals with the highest scores within

the various divisions of NICHD must be funded (within the available resources), even if they do not support NCMRR’s stated priorities. The report noted that the Medical Rehabilitation Coordinating Committee had “no effective mechanisms for tracking [rehabilitation-related research across NIH] or raising priorities within other Institutes, … [which results in] a discordant effort in which even the definitions of rehabilitation research vary among the Institutes” (IOM, 1997, p. 251). To provide NCMRR with more visibility and control over its planning and strategic priority setting, the 1997 IOM report proposed that NCMRR be elevated to the status of a freestanding center or institute within NIH. This recommendation is revisited later in this chapter.

The 1997 IOM report on disability viewed the rigor of the NIH peer-review process and the scientific standards for the conduct of research as strengths of NCMRR. It noted, however, that rehabilitation research lacked a dedicated application review study section. One benefit of making NCMRR a freestanding NIH institute was that it “could then form one or more special emphasis review committees managed by the Division of Research Grants” (IOM, 1997, p. 291). Such a group would review training grants, applications in response to RFAs, and certain other projects tightly linked to the agency’s missions.

The NCMRR review process has, however, changed since publication of the 1997 IOM report. All applications for training awards, major center grants, small grants (R03 grants), and awards for which applications have been requested are now reviewed by a peer review group constituted by NICHD (Michael Weinrich, Director, NCMRR,personal communication, November 9, 2006).8 Unsolicited applications for research project grants (R01 grants) go to the Center for Scientific Review (CSR).9 CSR manages the peer-review groups or study sections that evaluate the majority of NIH research grant applications. One question of concern to those involved in disability and rehabilitation research is whether CSR study sections tend to equate scientific rigor with a range of research designs that are more easily applied to medical and impairment interventions or studies than to psychosocial and participation research. A related and more general issue is whether the expertise represented in the study sections truly provides informed peer review of disability-related research proposals, especially those that focus more on psychosocial questions. In 2003, CSR created the

Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation Sciences study section, in which a majority of the members are rehabilitation and disability researchers.

VA Rehabilitation Research and Development Service

In 1948, the U.S. Congress authorized the Veterans Administration (now the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs) to undertake rehabilitation research and engineering projects with an initial emphasis on prosthetics (Reswick, 2002). Today, the mission of the VA RR&D is to support research relevant to veterans with chronic impairments that may lead to disability. Demands on the VA rehabilitation research program have recently increased as a result of the war in Iraq,10 and the system as a whole is facing significant financial challenges (see, e.g., Edsall [2005]).

Although veterans do not represent the full spectrum of people with disabilities or potentially disabling conditions (notably, children), nonveterans may also benefit from the knowledge generated by VA research. The areas of focus of the VA RR&D program include vocational, cognitive, visual, motor, sensory, amputation, cardiopulmonary, and general medical rehabilitation (VA, 2006b).

The VA RR&D program is one of four units in the Medical and Prosthetic Research program. The other units are the Clinical Science Research and Development Service, the Health Services Research and Development Service, and the Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service. (The funding for the Biomedical Laboratory Research program is larger than that for the first three programs combined [AAAS, 2006c].) Some disability-related research is undertaken in the Health Services Research and Development Service program.

VA RR&D is an intramural program, which means that it funds only the research conducted by VA employees (many of whom have joint appointments with academic institutions). VA scientists can, however, compete for research funding from NIH and other public and private sources. The program publishes the Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. The program supports 13 research centers of excellence. Some

are identified with health conditions (e.g., spinal cord injuries and brain injuries), whereas others are linked to assistive and other technologies (e.g., wheelchairs and functional electrical stimulation) (VA, 2006b). One center, which is sponsored jointly with the VA Health Services Research and Development Service program, focuses broadly on rehabilitation outcomes research for veterans with central nervous system damage.

One particular asset of the VA rehabilitation research program continues to be its association with a nationwide integrated health care system with strong patient and financial information systems (Perlin et al., 2004). The VA system can support large clinical trials involving multiple centers or sites across the country. The 1997 IOM report noted that “no other health care system, public or private, has a similar unified research program with the breadth and depth” of the VA program (p. 263). Because the VA combines a broad service mission and a research mission in a single agency and research is conducted by VA staff, the VA rehabilitation research program has a strong relationship with the population that it is intended to serve.

As Figure 10-1 shows, the budget for the VA rehabilitation research program was flat during the 1990s but increased from FY 2001 to FY 2005 as part of a general increase in agency spending on research and development. Investigator-initiated research projects account for about 54 percent of the total spending, and research centers account for about 27 percent (Ruff, 2006).

The 1997 IOM report noted no specific weakness in the VA rehabilitation research program and made no explicit recommendations for changes in the program. A 2004 Office of Management and Budget (OMB) review of the VA research and development overall described the research proposal review process as rigorous and managed “to assure scientific quality and fiscal soundness” (OMB, 2004, p. 38; see similar conclusions made by OMB [2005]). OMB (2004) also observed that the programs of research duplicated the activities of other public and private programs, but overall, it gave the VA research program good marks for research management and quality and compared it favorably with other similar programs. The committee is aware of criticisms of the research environment at VA, including excessive bureaucratic requirements, disincentives for outside researchers to collaborate with VA researchers, and workload concerns; but it was unable to investigate these issues.

Other Sponsors of Disability Research

As indicated above in Box 10-1, many federal agencies that do not have a specific mission to support disability do fund some disability research activities. The rest of this section briefly discusses a few of the more significant supporters of disability research among agencies that are not

primarily focused on such research. Other chapters have cited the research and data collection efforts supported by the U.S. Census Bureau, the U.S. Department of Transportation, the Social Security Administration, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the U.S. Department of Labor.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CDC is the federal government’s lead public health agency. In 1988, the U.S. Congress created the Disability and Health Program within the CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health and provided it with an appropriation of $3.8 million for activities related specifically to “the prevention of disabilities.” Today, the unit primarily responsible for broad disability issues, the Disability and Health Team, is lodged within the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities (NCBDDD), which, in turn, is part of Coordinating Center for Health Promotion.11

This placement represents a major organizational change since publication of the 1997 IOM report on disability. The change was required under the Children’s Health Act of 2000, which created NCBDDD and directed that it include, among other programs, the programs related to disability prevention that were formerly within the National Center for Environmental Health (42 U.S.C. 247b-4; CDC, 2001). Many of the staff and other resources were transferred from the Disabilities Prevention Program in the latter center. Because the Disability and Health Team is located within the CDC’s NCBDDD, no major CDC center or office currently focuses on disability across the life span as a primary topic.

Notwithstanding its location, the Disability and Health Team is concerned with the health of people with disabilities throughout the life span and gives its attention to health promotion, the prevention of secondary conditions, and access to preventive health care, as well as supports for family caregivers. It works with state health departments, universities, and national health and consumer organizations to develop and implement programs in these areas. For many years, it has particularly encouraged research and other attention to the understanding and prevention of secondary conditions as a source of increased disability and a target of rehabilitation interventions. The unit’s research also emphasizes health disparities among people with and without disabilities. It has funded re-

search to develop measures of environmental factors affecting people with disabilities, work that is consistent with efforts recommended in Chapters 2 and 5 of this report. CDC and NIDRR jointly support monitoring of the objectives in Healthy People 2010 related to disability and secondary conditions (DHHS, 2000a).

Core funding for the Disability and Health Team in FY 2006 totaled just under $10.6 million, down from $12.6 million in 1996 (John Crews, Lead Scientist, Disability & Health Program Team, personal communication, November 8, 2006).12 About $3 million was allocated for research specifically. Overall, the funds support program and scientific staff, 16 state programs, the American Association for Disability and Health, 11 research projects, and one information center. In addition to core funding, the unit is responsible for nearly $18 million to support several congressionally mandated programs, including the Amputee Coalition of America, the Special Olympics, and the Christopher and Dana Reeve Paralysis Resource Center.

For CDC as a whole, it is difficult to characterize research spending trends accurately or even to identify the total spending on disability research across all parts of the agency. Certainly, other parts of the agency support disability research. In any case, the level of funding for the research that is the focus of the Disability and Health Team has been and remains quite small.

Some other areas of CDC support research related to disability, most of which is focused on primary prevention. Within NCBDDD, the developmental disabilities program supports several centers of excellence for autism and developmental disabilities research. The Center for Injury Prevention and Control is funding a study of chronic pain prevention following spinal cord injury or limb loss (CDC, undated). Overall, CDC devotes about 8 percent of its funding to research of all kinds, about two-thirds of which supports extramural research (Spengler, 2005). (CDC’s total appropriation for FY 2006 was $6.2 billion, and funding from all sources was $8.5 billion, including funding from the U.S. Department of Defense for activities required to prepare for a possible influenza pandemic [CDC, 2006b].)

In report language for the 2005 appropriations bill for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and other agencies, the Senate Appropriations Committee urged “the CDC to significantly expand and strengthen its investment in the public health research, surveillance activities, and dissemination of scientific and programmatic health promotion and

wellness information for children and adults with disabilities” (U.S. Senate, Committee on Appropriations, 2004, p. 81). Unfortunately, the Congress did not allocate any funds specifically to support such an expansion.

As in 1997, the strengths of the Disability and Health Team remain its population-based approach to disability research and its persistence in directing attention to understanding and preventing secondary conditions. CDC overall continues to be a major actor in disability surveillance through the National Center for Health Statistics. Chapter 2 includes recommendations for improvements in this area.

The 1997 IOM report on disability noted that the Disability and Health Team’s lack of visibility within its parent organization was a weakness shared with other agencies. If anything, the organizational changes since 1997 appear to have further diminished the visibility of disability research within CDC or have at least obscured the unit’s concern with adult as well as childhood disability. The broader reorganization within CDC (e.g., the creation of four coordinating centers), whatever its merits, has in some respects further submerged chronic conditions and disabilities as areas of concern. The 1997 IOM report pointed to the need for more involvement in disability research by other parts of CDC, a view that this committee also supports.

National Science Foundation

NSF supports disability research in a number of areas, including assistive technologies, medical rehabilitation, prosthetic devices, universal access and universal design, sensory impairment, and mobility impairments (Devey, 2002; NSF, 2005). Within the Chemical, Bioengineering, Environmental, and Transport Systems Division, the Research to Aid Persons with Disabilities program specifically supports research and development that will lead to improved devices or software for people with physical or mental disabilities. It also funds projects that enlist students in the design of technologies to aid people with disabilities. The Research in Disabilities Education program, which is part of NSF’s Division of Human Resource Development, makes resources available to increase the levels of participation and achievement of people with disabilities in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education and careers. The program funds a broad range of projects to make education in these areas accessible and increase the quantity and quality of students with disabilities completing associate, baccalaureate, and graduate degrees in these fields.

Much of the research supported by NSF involves the development, evaluation, and refinement of both basic and sophisticated basic technologies. Examples of the latter include noise reduction techniques that may improve hearing aids, retinal prostheses for those with complete vision loss,

and “aware home” technologies that use sensors and sensor systems to support people with disabilities with independent living and the avoidance of institutionalization (Sanders, 2000; Devey, 2002, NSF, 2005).13

NSF did not supply yearly or trend data for disability research funding. A draft analysis prepared in 2002 by the NSF liaison to ICDR estimated that from FY 1998 to FY 2002, NSF supported 148 disability-related projects with funding of almost $73 million—an average of not quite $15 million per year (Devey, 2002). The Research in Disabilities Education program budget averaged $5 million per year from FY 2002 to FY 2006. For comparison purposes, the total NSF budget for FY 2002 was almost $4.8 billion (NSF, 2001).

The 1997 IOM report on disability noted a lack of coordination of NSF programs with other federal programs, “thus limiting the potential synergy among the projects being supported by other agencies” (p. 269). In the committee’s judgment, despite some improvement, this continues to be the case. The former executive secretary of ICDR recently moved to NSF, which could improve coordination.

Units of NIH Other than NCMRR

Beyond NCMRR, other institutes and centers of NIH support a range of disability research, although such research is not their primary focus. It is, however, difficult to identify the full array of disability and rehabilitation research funded throughout all the units of NIH. This may become easier in the future. The NIH Reform Act, which the U.S. Congress passed late in 2006, requires the NIH director to report to the Congress every 2 years on the state of biomedical and behavioral research. Among other information, the report is to include a catalog of research activities as well as a summary of research in several key areas, one of which is life stages, human development, and rehabilitation. In addition, the legislation provides for the creation of a research project data system that uniformly codes research grants and activities at NIH and that is searchable by public health area of interest.

NIH is also funding the development of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (generally referred to as PROMIS) to

|

13 |

NSF sponsors several Engineering Research Centers (ERCs) to promote interdisciplinary research and collaboration with industry (ERCA, 2006). The ERC for Biomimetic MicroElectronic Systems conducts research with the ultimate goal of developing implantable or portable microelectronic devices to treat blindness, paralysis, and memory loss. The mission of the ERC for Quality of Life Technology is improve quality of life by creating “a scientific and engineering knowledge base” for developing “human-centered intelligent systems that co-exist and co-work with people, particularly people with impairments” (Quality of Life Technology Center, 2006; see http://www.qolt.org/). |

improve measures of patient-reported symptoms and other health outcomes and make them more easily and widely used in clinical research and practice. For example, one goal is “to build an electronic Web-based resource for administering computerized adaptive tests, collecting self-report data, and reporting instant health assessments” (NIH, undated, unpaged; see also Fries et al. [2005]). The first areas identified for measurement development include pain, fatigue, emotional distress, physical functioning, and social role participation. (The initiative relied on the World Health Organization’s domains of physical, mental, and social health as its organizing framework.)

Several examples of important rehabilitation research at NIH outside NCMRR can be cited. Through its intramural Laboratory of Epidemiology, Demography and Biometry, the National Institute on Aging (NIA) has long supported research on the consequences of diseases on functioning and independence and the risk factors for disability, especially mobility disability (NIA, 2004; Guralnik, 2006). NIA’s extramural Behavioral and Social Science Research Program supports research and the collection of data on the individual and social dimensions of aging. It may be a model for supporting research within NIH that is not narrowly limited to a medical model of disability. The program funds research on the implications of population aging for health, retirement, disability, and families through its Centers on the Demography of Aging. It supports translational research on the health and well-being of older people and their families through its Roybal Centers. NIA has also funded national panel surveys related to disability, such as the National Long Term Care Survey and the Health and Retirement Study (see Chapter 2).

A number of other institutes also fund some disability research. A few additional examples include the following:

-

The National Institute of Nursing Research has funded research on formal and informal caregiving for people with chronic health conditions, and it sponsored a state-of-the-science meeting on informal caregiving in 2001 (NINR, 2001).

-

The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders supports work to develop assistive devices for people with impaired sensory and communications functions and to characterize and develop treatments for aphasia.

-

The National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering includes biomechanics and rehabilitation research among its extramural research program areas.

-

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke funds research on rehabilitation as well as research on the prevention and treatment of stroke, brain injuries, and various neuromuscular conditions.

-

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute has supported a number of clinical trials to test exercise training for cardiac rehabilitation.

Some NIH research, especially in the area of assistive technologies, is funded through the SBIR program, a competitive research award program that was created by the U.S. Congress in 1982 to stimulate technological innovation in the small business community (SBA, 2001). DHHS is 1 of 11 agencies that are required to have this kind of small business research support program. The U.S. Department of Education and NSF also participate. Another program, the Small Business Technology Transfer Program, emphasizes the successful movement of innovations from the research setting to the marketplace.

For the NIH overall, the NIH website reports that FY 2005 spending on rehabilitation research was $305 million of the total NIH budget for research and development of almost $28 billion (NIH, 2006a). (The NIH budget office did not respond to questions from the committee about how it developed these figures.) By way of additional context, NIH lists FY 2005 spending on aging at $2,415 million, spending on attention deficit disorder at $105 million, spending on multiple sclerosis at $110 million, and spending on obesity at $519 million NCMRR accounted for about a quarter of the 2005 NIH rehabilitation research spending.

In 1995, NIH identified that it spent $158 million on rehabilitation research. Given the amount of $305 million spent on rehabilitation research in FY 2005, the data suggest that, overall, rehabilitation research has not fully participated in the more than doubling of research funding that NIH has experienced since 1999.

The 1997 IOM report on disability developed an independent estimate of overall NIH funding of rehabilitation research.14 That estimate of $206 million for individual project funding was $46 million higher than the $158 million that NIH identified.15 This discrepancy likely reflects both the breadth and volume of NIH-sponsored research and the lack of a well-accepted and understood conceptualization of disability and rehabilita-

tion research within NIH. Some units of NIH may not have viewed their research projects as rehabilitation related. An appendix to the 1997 IOM report observed that “agencies seemed unsure of their own rehabilitation efforts, much less those of other agencies” (IOM, 1997, p. 326). Altogether, it is not possible to obtain a coherent picture of NIH disability research activities or trends, given the information currently available either from NIH itself or through ICDR (as discussed further below). This gap is addressed by the recommendations presented at the end of this chapter.

Other Units of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

A number of other units within DHHS undertake or support some disability research, although the committee found no systematic accounting of such work and was not able to assess the changes that have taken place since 1997. Examples of other units within DHHS that undertake or support disability research follow:

-

Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ). AHRQ funds health services and policy research, technology assessments, data collection, and other work in a variety of areas. When the agency was reauthorized in 1999, the U.S. Congress included, as a priority area for attention, individuals with special health care needs, including individuals with disabilities and individuals who need chronic care or end-of-life health care (Clancy and Andresen, 2002). Projects have included studies of the effects of managed care on children with chronic conditions, determinants of disability in people with chronic renal failure, and the levels of satisfaction with health care quality and access among people with disabilities. Several years of flat funding for this agency have limited its work in this and other priority areas.

-

Maternal and Child Health Bureau. This unit within the Health Resources and Services Administration funds data collection, research, and demonstration activities related, in particular, to children with special health care needs (see Chapter 4).

-

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chapters 8 and 9 described a number of this agency’s disability-related research projects.

-

Office of Disability, Aging, and Long-Term Care Policy in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. This office is responsible for a program of health services research and policy analysis to support the development and evolution of policies and programs that promote “the independence, productivity, health, and long-term care needs of children, working-age adults, and older persons with disabilities” (ASPE, 2005). The office supported the cash and counseling demonstration projects

-

discussed in Chapter 9. It recently funded an assessment of access to assistive technologies in long-term care facilities.

U.S. Department of Defense

The U.S. Department of Defense sponsors some research focused on the short- and long-term rehabilitation needs of military personnel, particularly those who have experienced spinal cord injuries, amputations, and traumatic brain injuries. For example, under the label “revolutionizing prosthetics,” the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency has initiated a project to “provide fully integrated limb replacements that enable victims of upper body limb loss to perform arm and hand tasks with [the] strength and dexterity of the natural limb,” based on advances in neural control, sensing, and other mechanisms that engage or mimic natural biological processes (Ling, 2005).

To cite another example, as part of a much broader portfolio of research, the Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center (TATRC), a unit of the United States Army Research and Materiel Command, manages several projects related to advanced prosthetics, orthotics, and rehabilitation through partnerships with federal agencies, academic institutions, and commercial firms (Kenneth Curley, Chief Scientist, TATRC, personal communication, November 8, 2006; see also http://www.tatrc.org). Projects range from a study of sports and quality of life for veterans with disabilities to an evaluation of amputee rehabilitation at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center to a more typical project on powered foot and ankle prostheses to improve maneuverability and reduce the effort required to operate the prostheses. The program recently assumed responsibilities for technology transfer to move program knowledge into the private sector.

CHALLENGES OF ORGANIZING AND COORDINATING DISABILITY RESEARCH

As illustrated throughout this report, disability is a broad domain ranging from physiological processes to social participation and government policies. Research on this domain cannot, therefore, realistically be within the purview of a single research funding agency. With so many agencies sponsoring some disability research, however, the lack of coordination in establishing and implementing priorities for the use of federal research resources is a continuing concern. The 1997 IOM report on disability argued that perhaps the single greatest consequence of disjointed federal research efforts was “the lack of an appropriate emphasis on disability research per se, that is, [research focused on] the interaction of the person and the physical and social environment” (p. 278).

Efforts to develop and coordinate a coherent program of disability research across federal agencies encounter a number of barriers. First, differences in agency missions and organizational cultures (e.g., the professional training and experience of staff and grantees) can make communication, cooperation, and priority setting difficult. The classic example of a culture gulf is between agencies informed by a medical model of disability and agencies informed by a social or environmentally determined model of disability.

Second, in advocating for research funding, sponsoring agencies typically “claim” the accomplishments of their particular research programs and projects. The competitive budget process thus provides incentives to maintain both the program applications and the funding within agency boundaries. In contrast, the incentives for productive coordination and collaboration are weak to nonexistent.

Third, the development and implementation of long-range strategic plans are, for the most part, conducted separately across agencies. In addition, research funding mechanisms, application deadlines, peer-review processes, and progress reporting and performance evaluation procedures differ across agencies. All of these differences make it complicated and frustrating to even attempt collaborative priority setting and to achieve adequate and timely funding of collaborative research initiatives.

In addition to coordination among research agencies that fund disability and rehabilitation research, coordination between agencies that fund disability and rehabilitation research and those that fund treatment and support services for individuals with disabilities is important if research that informs health care policy is to be planned and conducted efficiently. Although Medicare has adopted policies that allow it to pay for the routine clinical care provided during certain clinical trials,16 federal research agencies may still find it difficult to secure program payment for such care. For example, it may be difficult to coordinate coverage of routine care costs for a study that compares the care provided in a covered inpatient setting

with the care provided in an outpatient setting where the services would not normally be covered. Waivers have, however, been authorized for a number of demonstration projects testing payment mechanisms, coordinated care arrangements, and other purposes.17

Weak Coordinating Mechanisms

When the U.S. Congress created NIDRR, it also created ICDR, which had as its mission promoting the “coordination and cooperation among Federal departments and agencies conducting rehabilitation research programs” (ICDR, 2005). ICDR is housed within the U.S. Department of Education and is chaired by the director of NIDRR. It has 12 statutory members, including its chair, and representatives of 18 other agencies also attend meetings (ICDR, 2006).18 ICDR also has five subcommittees: Disability Statistics (1982), Technology (1996), Medical Rehabilitation (1997), Employment (2005), and New Freedom Initiative (2002). One goal of the medical rehabilitation subcommittee is to survey all federal medical rehabilitation projects, which would potentially help identify gaps in rehabilitation research and unproductive duplication.

The 1997 IOM report on disability noted “the ineffectiveness of ICDR as a federal coordinating body” (p. 259) and observed that it “has no staff, budget, or real control, and thus does not have the ability to carry out its stated mission” of coordinating federal disability research (p. 261). The Rehabilitation Act did not give ICDR the tools or the financial resources that it needs to compel or entice cooperation.

ICDR’s situation appears to have improved only modestly in recent years. Beginning in 2002, ICDR received funding for specific work to establish priorities for assistive and universally designed technologies and to promote collaborative public-private projects in these areas (ICDR, 2005). One product is the assistive technology report discussed in Chapter 7. In responses to questions from the committee, the director of NIDRR stated

that ICDR had produced more than 70 internal reports and literature reviews to assist its members in planning and coordinating priorities for their future research (Steven James Tingus, Chair, ICDR, and Director, NIDRR, personal communication, July 19, 2006.). In addition, ICDR is now meeting quarterly, and the level of attendance by member agencies has increased from an average of 13 per meeting from 1998 to 2003 to 17 per meeting from 2004 to 2006. The unit’s annual reports for the years 2004 and 2005 are, however, overdue, although the committee understands that the delay reflects, in part, clearance delays within the U.S. Department of Education.

In 2003, ICDR revised its administrative structure and resources (ICDR, 2005). For example, it created an internal website (an intranet) to support communications among committee and subcommittee members. It is also attempting to design an Internet-based system to simplify the collection of information from different federal agencies about their research portfolios that would help to identify research gaps and duplication and to coordinate research in different areas. This work is ongoing but has not reached the point of allowing ICDR to generate an accurate and comprehensive federal government-wide compilation of disability research and research funding. Nonetheless, although the work is only a small part of the larger problem of inadequate information and coordination, the movement is in the right direction.

Within NIH, the role of the NCMRR Medical Rehabilitation Coordinating Committee likewise does not match its title. A 1993 research plan for NCMRR said that the coordinating committee “will work to develop a method of reporting, coordinating and developing medical rehabilitation research initiatives at the NIH” (NICHD, 1993). That early objective has not been met. The 1997 IOM report stated that “meaningful coordination seems to be lacking” at NIH, resulting in “a discordant effort in which even the definitions of rehabilitation-related research vary among the institutes” (p. 251).

A few single or multiagency coordinating committees are concerned with particular health conditions, for example, autism and muscular dystrophy. The narrower focus of such groups might plausibly make their coordinating task somewhat easier, but this is speculative.

In the face of the barriers described above, ICDR fails as an instrument for coordinating disability research across federal agencies. As described above, it lacks the authority or incentives to command or entice attention and cooperation from powerful agencies such as NIH and VA. It serves largely as a communication conduit for agencies to learn more about each other’s research activities and areas of mutual interest or complementary expertise. This is a worthy function but a weak coordination tool. Within

NIH, the Medical Rehabilitation Coordinating Committee appears to be even less significant as a means of coordinating disability research.

ICDR’s recent acquisition of resources to undertake some data collection and analytical work is helpful. It is, however, likely to be useful mainly as an educational tool—absent any incentives for agencies to cooperate if problems of duplication or insufficient attention to research areas are identified. In this context of interdepartmental relationships, information does not equal power. One bright spot elsewhere is the recent legislative mandate described above for NIH to create an improved research database.

In discussing the advantages of the recommended move of NIDRR to DHHS, the 1997 IOM report noted that this step would move the program closer to NIH and CDC. The report also recommended the creation within the relocated agency of a “coordination and linkage division” that would assume the responsibilities of ICDR and that would also be funded and authorized to support collaborative research.

As discussed further below, the current committee recommends reinforcing ICDR’s responsibilities for collecting and analyzing information on the federal government-wide disability research portfolio. Additional information does nothing directly about the structural barriers to coordination, but it provides a basis for a more informed discussion about the appropriate distribution of the research effort.

A recent example may illustrate a lost opportunity for interagency collaboration and may suggest a strategy that could be used to enhance such collaboration in the future. For many years, NIDRR has funded the Traumatic Brain Injury Model System program, in which a set of centers collects longitudinal data on individuals with moderate and severe brain injuries. This program has gathered a cadre of investigators interested in the condition, has established a research and data collection infrastructure, and has developed a registry of affected individuals for whom a set of standardized severity information is available. Funding for these grants is, however, insufficient to support ambitious clinical trials. In 2001, NCMRR announced a competition for the Traumatic Brain Injury Clinical Trials Network (NCMRR, 2001). That program sought to establish a set of centers that could enroll individuals with moderate and severe brain injuries in clinical trials of acute care and rehabilitation. Its development and implementation included no systematic collaboration with NIDRR, even though five of the eight funded centers were also NIDRR-funded model systems. The NCMRR system developed a separate data collection infrastructure. The lack of collaboration meant that some institutions competed for patients for separately funded protocols and also had to support some redundancy in administrative infrastructure. Strategic collaboration and coordination could have yielded at least two more-efficient or productive alternative arrangements. For example, the two agencies could have agreed

that NIDRR would continue to fund the research infrastructure and that NCMRR funds would be used to support costly clinical trials conducted within the model system structure. Alternatively, the agencies could have agreed that the field needed a larger set of clinical trial sites with a different research focus, leading to specific efforts to fund appropriate sites that were not already model systems.

Continued Need for Capacity Building

As it is understood broadly, research capacity consists of several interrelated elements. They are (1) researchers in sufficient numbers and with appropriate experience and skills to conduct socially valued and ethically sound research, (2) educational programs that produce these researchers, (3) research and analytical methods and ethical standards suitable for the problems to be investigated, (4) institutional settings with the necessary administrative and physical resources to manage research and with the necessary leadership to stimulate good science and attract and retain good investigators, (5) mechanisms of accountability for research conduct, and (6) public and private funding and policies to support the enterprise. Given the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in disability research, mechanisms of support for such collaborative research can be viewed as another element of research capacity. The support for translational research mentioned at the end of this section is an example.

Although this committee did not have the resources required to update the work of the 1997 IOM committee on research capacity, a recent rehabilitation research summit identified a number of problems that echo many of those identified in the 1997 report and that are likewise consistent with this committee’s experience (Frontera et al., 2006). Summit participants, who included rehabilitation researchers, research funders, professional organizations, consumer representatives, and others, cited the following problems:

-

Insufficient numbers of adequately prepared rehabilitation researchers

-

Minimal recognition of the value of scientific research by relevant professional and clinical organizations and academic rehabilitation institutions

-

Inadequate funding to support superior rehabilitation research education programs and training opportunities

-

Limited models of interdisciplinary collaboration, which is important, given the diversity of people, interventions, and environments that are the subject of rehabilitation (disability) research

-

Weak partnerships with different professional and academic groups and consumer groups

-

A lack of an effective strategy of advocacy to build support for rehabilitation research from government agencies and academic institutions

Although the emphasis of the summit meeting was on rehabilitation research, many of the issues—including the continuing difficulties in defining disability and its dimensions—extend to other areas of disability research.

Implicit in much of the summit’s discussion of shortfalls was a concern that research on disability—especially research focused on social integration and participation—is not valued within the larger research and academic communities and is valued more in word than in deed by policy makers and the public. The latter gap shows itself in the public funding of disability research, which is dwarfed by the funding for basic and clinical research on medical conditions.

Although infrequently recognized as such, rehabilitation science is a fertile domain for translational research. The breadth of the domain, as described earlier, requires collaborative “team science” across the domains of disability. Advances in basic fields such as neuroscience and tissue engineering provide new tools, but the notion of “translation” needs to be broadened beyond molecular medicine to include the translation of basic research on learning processes, behavioral adaptation, and a variety of other domains into day-to-day clinical decision making and practice and into relevant public and private programs. Chapter 7 described the limitations of current translation research efforts related to assistive and accessible technologies.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Directions for Research

This chapter has focused on the organization and funding of disability research. Earlier chapters discussed research on topics covered in the committee’s charge.

The 1991 IOM report on disability presented a research agenda that emphasized the primary prevention of developmental, injury-related, and aging-related chronic conditions that contribute to disability. It also discussed research on the tertiary prevention of secondary health conditions related to chronic health conditions. Since publication of the 1991 report, research has advanced in these and other areas, including the understanding of risk factors related to the onset of disability at birth and throughout the life span.

For example, investigators have identified environmental risk factors—such as living in socioeconomically disadvantaged families and in households with exposures to environmental toxins—for childhood disability

(see, e.g., Hogan et al. [2000]). In late life, researchers have identified potentially modifiable risk factors for functional decline, including a low frequency of social contacts, a low level of physical activity, smoking, and vision impairment (see, e.g., Stuck et al. [1999]). Researchers have also identified some promising interventions to limit disability in late life, including chronic disease self-management programs, physical activity programs, and multifactor fall prevention interventions (Center for the Advancement of Health, 2000a,b).

Still, earlier chapters of this report make it clear that many gaps remain in the knowledge base for practices and programs that reduce environmental barriers that restrict the independence, productivity, and participation in community life of people with disabilities. In addition, translating the findings of social and behavioral research into practice remains a formidable challenge in this and other areas (IOM, 2000b). Determining how best to promote activity and participation for people of all ages and abilities will require resources to develop, test, and disseminate promising interventions, practices, and programs. Given the disincentives to private investment described in Chapter 7, the federal government has a central role to play in developing and implementing an intervention research agenda focused on activity limitations, participation restrictions, and quality of life for people with disabilities. It will be important for the process to involve people with disabilities as well as private companies and foundations.

Recommendation 10.1: Federal agencies should invest in a coordinated program to develop, test, and disseminate promising interventions, practices, and programs to minimize activity limitations and participations restrictions and improve the quality of life of people with disabilities.

Increasing the Funding and Visibility of Federal Disability Research

The 1997 IOM report on disability bluntly stated that the combined federal research effort was not adequate to address the needs of people with disabilities and that more funding would be required to expand research to meet these needs. Despite modest increases in funding during the late 1990s, the situation remains essentially the same 10 years later.

Disability research is a miniscule item in the federal government’s research budget; and the federal government’s funding for disability research is not in line with the current and, particularly, the future projected impact of disability on individuals, families, and American society. This committee reiterates the call in the 1997 IOM report for increased funding for disability research, which is becoming increasingly urgent in light of the

approaching large increase in the numbers of people at highest risk of disability, as described in Chapter 1.

An overarching recommendation—and appeal—in the 1997 IOM report was that “rehabilitation science and engineering should be more widely recognized and accepted as an academic and scientific field of study” (p. 297). The research funding provided by the federal government is a powerful indicator of a field’s recognition and acceptance. Since 1997, the field of rehabilitation research—and, more broadly, the field of disability research—has made a few gains in research funding at the federal level, but the overall federal funding picture remains as muddled and murky as it was in 1997.

Likewise, disability research still lacks adequate visibility and recognition within the federal bureaucracy. In fact, for most federal agencies, the committee discovered that it was extremely challenging to even identify the level and extent of disability research being supported by each agency. Therefore, this committee reiterates the call made in the 1997 IOM report for actions to be taken to increase the visibility of federal rehabilitation and disability research within federal research agencies. It again proposes that the U.S. Congress consider elevating NCMRR to the level of an independent center or freestanding institute within NIH. Doing so will create a much more visible entity within NIH that has disability and rehabilitation research as its primary mission and that appropriately occupies an organizational level that is comparable to that of the other institutes.

The committee is aware that the National Institutes of Health Reform Act of 2006, passed in December 2006 (3 months after the committee’s last meeting), capped the number of freestanding NIH institutes and centers at 27 (the existing number). Although the new legislation is understandable in the larger context of research policy, it places a powerful and discouraging constraint on efforts to give disability and rehabilitation research a greater presence and independence in NIH and in the larger research community as well.

The committee also reiterates the suggestion in the 1997 IOM report for the creation of an Office of Disability and Health (similar to the Office of Minority Health and the Office of Women’s Health) in the Director’s Office at CDC to promote integration of disability issues into all CDC programs. Disability is an issue that crosses all age, gender, racial, and geographic groups and all dimensions of public health, a reality that is confused by the current location of the Disability and Health Team within a center focused on birth defects and developmental disabilities. Creating a presence within the Director’s Office should help direct attention to disability issues across CDC and thereby support the Disability and Health Team.

As in 1997, the weak position of NIDRR in the U.S. Department of Education continues to be a source of concern. The committee considered

reiterating the recommendation made in the 1997 report that NIDRR be moved out of the U.S. Department of Education into DHHS (as the Agency on Disability and Rehabilitation Research). Still, the committee recognizes the improvements undertaken and planned in the NIDRR review process and encourages continued efforts to build on these improvements and address continuing shortcomings in the process. Given the constructive steps at NIDRR in its current location and given the agency’s unique focus on research that addresses the interaction of the person and the environment as strengths of the agency, the committee does not repeat the 1997 recommendation to move NIDRR out of the U.S. Department of Education. Rather, it calls for the department to support the agency’s efforts to strengthen the quality and scope of its research portfolio.

As in 1997, the committee does not recommend the creation of a new umbrella agency that consolidates all rehabilitation research. Such a step would now, as then, require “uprooting and displacing many meritorious programs” and would reduce the variety of perspectives and approaches to disability issues found in existing agencies (IOM, 1997, p. 280).

Recommendation 10.2: To support a program of disability research that is commensurate with the need for better knowledge about all aspects of disability at the individual and societal level, Congress should increase total public funding for disability research. To strengthen the management and raise the profile of this research, Congress should also consider

-

elevating the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research to the status of a full institute or free standing center within the National Institutes of Health with its own budget;

-

creating an Office of Disability and Health in the Directors Office at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to promote integration of disability issues into all CDC programs; and

-

directing the Department of Education to support the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research in continuing to upgrade its research review process and grants program administration.

Improving Disability Research Coordination and Collaboration

The inadequate coordination of disability research was highlighted in the 1997 IOM report on disability, and it remains a persistent problem today. With tightening federal budgets, the advantages of coordination—to avoid neglect or an insufficient emphasis on important issues, wasteful duplication, and the inefficient use of resources—are even more important today than they were in 1997. More than 30 years after amendments to the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 promoted the coordination of federal dis-

ability research, it is lamentable that it remains difficult to determine even the amount and the type of disability research being conducted by programs scattered across multiple federal departments.

It is also dismaying that the ICDR, which has the congressionally established responsibility of coordinating disability research, remains a weak instrument for this purpose. The U.S. Congress and the U.S. Department of Education have made some extra resources available to ICDR in recent years, and the unit is taking steps to identify and describe federal disability research activities in selected areas. Nonetheless, further action is needed to improve coordination.

The committee recognizes the challenges of coordination, especially coordination involving multiple federal departments and independent agencies with diverse missions. Indeed, coordination is difficult even within single agencies, especially those in large and complex organizations like NIH that have components with substantial independence. Like reorganization, coordination is not cost free. It is often (sometimes correctly) perceived as a largely symbolic or wishful exercise that absorbs time and energy with minimal benefit. The committee also acknowledges the lack of response to the 1997 IOM report’s recommendation to relocate NIDRR and strengthen the resources for coordination available to the relocated agency. Nonetheless, an adequately funded mechanism to undertake certain basic coordination tasks is important for the reasons outlined earlier in this chapter.

Recommendation 10.3: To facilitate cross agency strategic planning and priority setting around disability research and to expand efforts to reduce duplication across agencies engaged in disability research, Congress should authorize and fund the Interagency Committee on Disability Research to

-

undertake a government-wide inventory of disability research activities using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health;

-

identify underemphasized or duplicative areas of research;

-

develop priorities for research that would benefit from multiagency collaboration;

-

collaborate with individual agencies to review, fund, and administer this research portfolio; and

-

appoint a public-private advisory committee that actively involves people with disability and other relevant stakeholders to advise on the above activities.

As recommended above, one mundane but important task of a better-resourced ICDR would be to inventory and categorize government research activities and funding. One activity of the public-private advisory group