|

2 The U.S. Global AIDS Initiative: Context and Background Summary of Key Points

|

2

The U.S. Global AIDS Initiative: Context and Background

The first half of this chapter provides a brief overview of the HIV/AIDS pandemic; identifies some of the key partners responding to the pandemic; and explores the global context for implementing HIV/AIDS programs, including challenges faced by all donor programs. The second half provides an introduction to the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) focus countries and describes the legislation that created the program.

THE HIV/AIDS PANDEMIC

The HIV/AIDS pandemic has already claimed more than 25 million lives. Cases have been reported in all regions of the world, but most people living with HIV/AIDS (95 percent) reside in low- and middle-income countries, where most new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths occur.

The year 2006 marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the description of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). AIDS was first recognized among gay men in the United States. By 1983, the etiological agent of the disease, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), had been identified. By 1985, at least one case of HIV infection had been reported in each region of the world (UNAIDS, 2006). The 1980s also marked the pandemic status of HIV/AIDS, which has been increasing in incidence and prevalence globally ever since. The nature of the virus is such that without intervention, only a minuscule proportion of HIV-positive individuals will not progress to AIDS, and predictably to death from AIDS and its complications. The twenty-fifth

anniversary of the identification of AIDS was marked by numerous histories, perspective reviews, and publications. Appendix D provides a short list of sources offering more detailed global overviews.

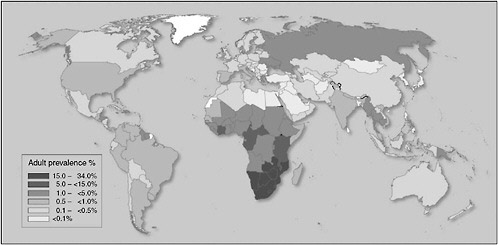

Figure 2-1 shows a global view of the prevalence of HIV/AIDS, with the majority of cases occurring in low- and middle-income countries (UNAIDS, 2006; WHO, 2006a). The nations of sub-Saharan Africa are the hardest hit, but concern is increasing about the next wave of the pandemic that is emerging in parts of Eastern Europe and Asia. AIDS is the leading cause of death worldwide among those aged 15 to 59 (UNAIDS, 2006). The pandemic is also considered a threat to the economic well-being and social and political stability of many nations (UN, 2003b; CSIS, 2005; Rice, 2006). The stark facts are these (UNAIDS, 2006):

-

More than 39 million people are living with HIV/AIDS worldwide, twice the number in 1995.

-

During 2006, more than 4 million people became infected with HIV, including more than half a million children.

-

Nearly 3 million people died of AIDS-related illnesses in 2006.

-

Worldwide, most people living with HIV are unaware that they are infected.

-

At any given time, many more people are infected—are HIV-positive—than are clinically ill with AIDS.

Although undeniably pandemic, HIV/AIDS can best be addressed if it is viewed as many separate epidemics with distinct origins and characteristics of spread. The epidemics can be described in terms of geography or of subpopulations affected within larger populations, and involve different transmission patterns that result from varying patterns of behaviors conducive to spread of the virus. The main methods of transmission are sexual contact, blood exposure from injecting drug use involving shared needles, and transmission from mother to child before or during childbirth. Other methods of transmission that may be especially important focally are blood transfusions from people who are HIV-positive, medical accidents, and unsafe medical injection practices. It is estimated that in sub-Saharan Africa, transmission through sexual contact, from mother to child, and via health care procedures (including blood transfusions and medical injections) account for 80–90 percent, 5–35 percent, and 5–10 percent of new infections, respectively, with regional variation (NAS, 1994; Quinn et al., 1994; Quinn, 1996, 2001; WHO, 2002b; Askew and Berer, 2003; Bertozzi et al., 2006).

Bertozzi and colleagues (2006) classified country-level AIDS epidemics into three states: low, concentrated, and generalized, with numeric indicators for HIV prevalence among populations (see Table 2-1). In the low state, HIV infection has not spread to significant levels in any subpopulation and

TABLE 2-1 Classification of Country-Level AIDS Epidemics

|

Extent of HIV Infection |

Highest Prevalence in a Key Population (percentage)* |

Prevalence in the General Population (percentage) |

|

Low |

<5 |

<1 |

|

Concentrated |

>5 |

<1 |

|

Generalized Low |

≥5 |

1–10 |

|

Generalized High |

≥5 |

≥10 |

|

*Key populations include sex workers, men who have sex with men, and people who use injecting drugs. SOURCE: Bertozzi et al., 2006. |

||

is largely confined to individuals with higher-risk behaviors, such as sex workers, people who use injecting drugs, and men who have sex with other men. This epidemic state suggests that networks of those at high risk are diffuse (that is, low levels of partner exchange or sharing of drug-injecting equipment) or that the virus has been introduced relatively recently. No focus country epidemic is characterized by this state.

In the concentrated state, HIV has spread rapidly in a defined subpopulation but is not well established in the general population. This state suggests active networks of risk within the subpopulation, and the future course of the epidemic is determined by the frequency and nature of links between the highly infected subpopulation and the general population.

In the generalized state, HIV is firmly established in the general population. Although subpopulations at high risk may continue to contribute disproportionately to the spread of HIV, sexual networking in the general population is sufficient to sustain an epidemic independent of subpopulations at higher risk of infection. Low and high subcategories of the generalized epidemic are recognized.

THE GLOBAL RESPONSE TO HIV/AIDS IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD

Major Funding Sources for HIV/AIDS Assistance

In response to the intensifying global HIV/AIDS crisis, international funding for HIV/AIDS programs has increased steadily since 2001. In 2005, commitments from donor governments to respond to HIV/AIDS rose to $4.3 billion, up from $3.6 billion in the previous year (Kates and Lief, 2006).

U.S. funding to combat global HIV/AIDS has steadily increased since 2001 (see Table 2-2). In 2006 PEPFAR contributed 26 percent of official

TABLE 2-2 Total U.S. Funding for Global HIV/AIDS for Fiscal Years 2001–2007 (in millions of U.S. dollars)

|

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008* |

|

785 |

1,083 |

1,540 |

2,311 |

2,719 |

3,290 |

4,556 |

5,400 |

|

*Proposed. SOURCE: OGAC, 2007a. |

|||||||

development assistance1 from donor governments for programs to address global HIV/AIDS (OGAC, 2005b, 2006a; Kates and Lief, 2006).

The U.S. Global AIDS Initiative is one of several significant sources of international HIV/AIDS assistance. Multilateral organizations—such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund); the World Bank; and UNAIDS, which coordinates the various United Nations (UN) agencies2—are also primary providers of international HIV/AIDS funding (UNAIDS, 2005b). These key global partners for the U.S. Global AIDS Initiative are briefly described in Box 2-1.

Governments of affected countries have also increased their spending, with amounts depending on, among other factors, gross national income, national debt, political stability, and the status of the working class (Kates and Lief, 2006). The private sector (including foundations, corporations, international nongovernmental organizations, and individuals) represent another vital funding stream for responses to HIV/AIDS. U.S.-based philanthropies committed an estimated $395 million in 2003 to HIV/AIDS activities in the United States and internationally, with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation making the greatest contribution. International development banks, including the Inter-American Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, and the African Development Bank, play contributory roles as well (Kates and Lief, 2006). The Joint United Nations Programme

|

BOX 2-1 Multilateral Organizations Contributing to Responses to Global HIV/AIDS The Global Fund was created in 2001 as an independent public–private partnership with the intent of providing grants to countries to finance programs targeting AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. As of July 2006, about $9 billion had been pledged to the Global Fund from all sources, and $5.5 billion had been committed to 132 countries. Fifty-seven percent of the funds had been allocated to HIV/AIDS (Global Fund, 2005, 2006). The World Bank began supporting HIV/AIDS programming in 1986, and has since launched major efforts in Africa (2000) and the Caribbean (2001) through its Multi-Country AIDS Program. The World Bank also offers financial assistance for HIV/AIDS programs through the Inter national Development Association, which provides grants and interest-free loans to the world’s poorest countries, and through the Inter national Bank for Reconstruction and Development, which offers nonconcessional loans to countries able to repay them. The majority of funds are derived directly from member country contributions, primarily from the G8. As of April 2006, the World Bank had committed a total of $2.6 billion to combat HIV/AIDS, approximately $1.9 billion of which was distributed through the International Development Association (Kates and Lief, 2006). UNAIDS, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, brings together the efforts and resources of 10 UN agencies to help the world prevent new HIV infections, care for those already infected, and mitigate the impact of the pandemic. UNAIDS is based in Geneva and works on the ground in more than 75 countries. Established in 1994 by a resolution of the UN Economic and Social Council and launched in January 1996, the organization is guided by a Programme Coordinating Board including representatives of 22 governments from all geographic regions; the UNAIDS Cosponsors; and five representatives of nongovernmental organizations, including associations of people living with HIV (UNAIDS, 2007). HIV/AIDS funding from the UN increased from $1.3 billion for 2004–2005 to $2.6 billion for the 2006–2007 budget (UNAIDS, 2003, 2005c). |

on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimates spending from all of these sources at approximately $2.1 billion for 2005.

Despite the large sums of money available, funding is far below what is needed (UNAIDS, 2006). A publication from the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation entitled International Assistance for HIV/AIDS in the Developing World: Taking Stock of the G8, Other Donor Governments and the European Commission, available at http://www.kff.org, provides an in-depth review of international donor assistance for HIV/AIDS efforts.

Global Efforts to Improve Coordination Among Donors

The scope and size of the U.S. Global AIDS Initiative are closer to the scale of a multilateral than a bilateral effort, and while the United States is not the only donor of funding for HIV/AIDS programs, in some countries its magnitude makes it a dominant source and thus influential in policy and program development. In 2005, the UNAIDS Secretariat convened leaders from governments and the civil sector, UN agencies, and other multinational and international organizations to review the global response to HIV/AIDS. Issues such as the absorptive capacity of developing countries, duplication of effort among donors, gaps in funding, and the burden on countries for reporting results and administering the funds were examined. The magnitude of PEPFAR and its contributions to the increase in funding were also recognized and considered. These examinations prompted the formation of the Global Task Team, whose primary purpose was to improve HIV/AIDS coordination among multilateral institutions and international donors. The ultimate goal was to accelerate global action to achieve significant progress toward international goals for the delivery of services to people affected by the epidemics in low- and middle-income countries by making recommendations for addressing the above issues (UNAIDS, 2005a). The Global Task Team comprised representatives from 24 countries and institutions, and its work was facilitated by three working groups. Officials from the Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator (OGAC) participated in the working group on harmonization of monitoring and evaluation, which made recommendations for improving policies, systems, and practices of multilateral institutions, as well as global initiatives to coordinate and improve monitoring and evaluation systems (UNAIDS, 2005a). The expectation for aligning the work of the Global Task Team with the Three Ones principles of harmonization (discussed further later in this chapter) was expressed early in the process (UNAIDS, 2005a).

To implement the recommendations of the Global Task Team, the Global Implementation Support Team was formed in July 2005. By November 2006, the Global Implementation Support Team had expanded and included additional representatives from the civil sector and bilateral donors, including the U.S. Global AIDS Initiative. The Global Implementation Support Team “centers on country-driven problem solving to unblock obstacles to accelerated grant implementation … [with] members meeting on a monthly basis to review immediate and medium-term technical support needs, make decisions on joint and coordinated technical support to be provided, evaluate progress and assess performance of such support, and look at ways to improve interaction between Global Implementation Support Team member organizations and countries” (GIST, 2006, p. 1).

HARMONIZATION IN THE GLOBAL RESPONSE TO HIV/AIDS

Evolution of the Three Ones Principles of Harmonization

Significant global events and economic development agreements were the precursors to the formal drafting of and commitment to what would become known as the Three Ones principles of harmonization (see Box 2-2). These principles were “specifically developed to cope with the urgency and need to ensure effective and efficient use of resources and focus on delivering results—in ways that will also enhance national capacity to deal with the AIDS crisis long-term” (UNAIDS, 2004b, p. 1). Though developed to foster improved coordination of HIV/AIDS responses, the principles were designed to be fully compatible with the guidelines of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee for “Harmonising Donor Practices for Effective Aid Delivery” and the February 2003 “The Rome Declaration on Harmonisation” by “accommodating different aid modalities while ensuring effective management procedures and reducing transaction costs for countries” (OECD, 2003; The Rome Declaration, 2003; UNAIDS, 2004b, p. 1), as well as with the concept of national ownership described in the “Monterrey Consensus,” which provides the framework for national ownership of social and economic development (UN, 2003a).

In April 2004, UNAIDS, the United Kingdom, and the United States co-hosted a high-level meeting at which all major donors and programs (including PEPFAR) formally endorsed the Three Ones principles of harmonization (UNAIDS, 2004a). A primary intent of harmonization is to reinforce the consistency and simplification of policies, practices, and procedures among donors (UNAIDS, 2004b).

|

BOX 2-2 The Three Ones Principles for the Harmonization of National HIV/AIDS Responses

SOURCE: UNAIDS, 2004a. |

One HIV/AIDS Action Framework

The first principle of harmonization requires broad participation in the development, review, and periodic update of the national framework for HIV/AIDS response, as well as in its successful implementation. Broad participation of key stakeholders in the governmental, private, civil, and international sectors is also expected to contribute to the quality and comprehensiveness of the framework (UNAIDS, 2005d). Stakeholder participation applies not only to implementation and innovation, but also to public policy, advocacy, and oversight functions such as monitoring and evaluation (UNAIDS, 2004b). National ownership of participatory planning and execution, which is becoming increasingly common, is critical. National ownership has many elements, but key is both the respect and continued support of donors for national governments, as well as strong leadership, governance, communication, and transparency on the part of both national entities and donors (UNAIDS, 2004a, 2005d). National frameworks require work plans and budgets that can be tracked, especially to coordinate the support of donors and other stakeholders (UNAIDS, 2005d). Frameworks that have these plans and budgets are often characterized as being prioritized and costed.

One National HIV/AIDS Coordinating Authority

UNAIDS has stated that developing, reviewing, and updating national plans requires human resource capacity for coordination and calls for strong leadership and commitment, which are ideally provided by the highest level of government. This highest level of government is also expected to delegate its authority to a national AIDS authority, which may include a governing council and a secretariat, that also has a mandate to broadly recruit other national, local, and international stakeholders from all sectors into the collaborative process and to coordinate all action related to that process. The complex dynamics seen in several countries among the various stakeholders have demonstrated the need for effective leadership and coordination to maximize the contributions made by all (UNAIDS, 2005d).

One Monitoring and Evaluation System

Monitoring and evaluation of activities can facilitate the allocation of limited resources to the best advantage and provide information needed for a country and its partners to respond to emerging trends in the epidemic in a timely manner. UNAIDS recommends that monitoring and evaluation occur in the context of a unified national strategic plan for these activities, with the country adopting a single set of standardized indicators endorsed

by all stakeholders and using a national information system that ensures the effective flow of information at all levels (UNAIDS, 2005d).

While they are essential activities, monitoring and evaluation pose a tremendous challenge. UNAIDS has described three directions of accountability—upward to donors of all types, downward to people directly affected by HIV/AIDS, and horizontally within and across partnerships and to the civil sector to encourage mutual accountability (UNAIDS, 2004b). According to UNAIDS, “a central focus for accountability in this situation is to strengthen partner countries’ capacity to manage and monitor so that reporting can be country-led and country-owned and reporting and monitoring should support the partner countries’ own needs. Credible monitoring and evaluation must serve two essential functions: to improve programme implementation, while also allowing donor sources to ensure that their funding is effectively spent” (UNAIDS, 2004b, p. 3). Follow-up to the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS has shown that among the challenges faced by countries and their partners are weak collaboration among stakeholders; shortages of monitoring and evaluation skills; insufficient resources to support the activities; and a lack of the strategic information systems needed to collect, analyze, and report the data (UNAIDS, 2005d).

Strategic Planning and Major Elements of HIV/AIDS Programs at the Country Level

As early as 1998, UNAIDS published a guide for countries to assist them in developing national strategic plans for their response to HIV/AIDS. The guidelines offer practical assistance for planning at the national, district, and community levels by governments, nongovernmental organizations, donors, and other agencies (UNAIDS, 1998). The major steps or strategic planning at the country level as outlined by UNAIDS are listed in Box 2-3.

Strategic planning may result in different priorities in different countries, but the major elements of all HIV/AIDS programs are similar (see Box 2-4). Interventions and services involve both help for those living with HIV/AIDS or otherwise affected by the epidemic (for example, children orphaned because of AIDS and family members of people who are HIV-positive) and efforts to curtail the spread of the virus through a variety of measures.

A Family-Centered and Community-Based Approach to HIV/AIDS

Programs can be offered in a variety of settings, but UNAIDS has urged that services be available in the communities where those affected live and

|

BOX 2-3 UNAIDS Guidelines on Major Steps of Strategic Planning at the Country Level

SOURCE: UNAIDS, 1998. |

to families, which are the main source of support and care for people with HIV/AIDS. With a few exceptions, however, community-based primary health care services are fragmented, have inadequate resources, and place “little emphasis on health promotion, prevention, and systematic screening and referrals” (WHO, 2002a, p. 1). Remedying this situation means supporting and strengthening local capacity to provide all necessary services (UNAIDS, 2001).

A healthy community has been described as “one that is continually creating and improving physical and social environments and expanding those community resources which enable people to mutually support each other in performing all the functions of life and developing to their maximum potential.” An empowered community must have both a system to provide help, including both formal and informal elements, and an empowered and mobilized citizenry (Kaye and Wolff, 2002, pp. 1–2). Local communities, even when composed mainly of people who are illiterate, have the capacity to work as partners with governments, with health and development agencies, and with nongovernmental organizations in identifying local priorities and implementing appropriate strategies (WHO, 2002a). These issues are discussed further in Chapter 6.

|

BOX 2-4 Major Elements of HIV/AIDS Programs Identified by UNAIDS

SOURCE: UNAIDS, 2005b. |

CHALLENGES TO HIV/AIDS PROGRAMS

Even assuming harmonization among stakeholders, countries and their assistance partners are faced with myriad challenges to successful implementation of HIV/AIDS programs. These challenges include economic and social conditions; the capacity of health care systems; the capacity of the health care workforce; competing health priorities, the increasing burden of HIV/AIDS on women and girls; growing numbers of orphans and other vulnerable children; the increasing need for children and grandmothers to serve as caregivers; stigma and discrimination; and gaps in the current evidence base for the prevention, care, and treatment of people with HIV/AIDS. These challenges are highlighted briefly here and discussed further in the subsequent chapters. With the levels of aid being provided and the infusion of commodities, the potential for corruption is another challenge countries face (Lyman, 2005). However, an examination of the kind necessary to detect corruption was beyond the scope of this study (see Chapter 1 and Appendix B for discussion of data and methods).

Economic and Social Conditions

The countries hardest hit by HIV/AIDS are among the poorest in the world. AIDS has been identified as a serious challenge to development, with both short- and long-term economic effects (UNAIDS, 2006). Because HIV/AIDS often hits working-age populations hardest, the workforces of many nations have been affected by the loss of skilled workers to the epidemic. This loss of skilled workers in turn affects nations’ ability to respond to their epidemics. (The special case of the health care workforce is discussed below.)

The education sector in many countries has been severely affected. A growing number of studies have been examining the impact of HIV/AIDS on education, including supply, demand, and quality. As early as December 1999, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) reported that the “educational systems of much of Eastern and Southern Africa were experiencing problems due to absenteeism and the loss of teachers, education officers, inspectors, and planning and management personnel” (Africa Renewal, 1999, p. 1). In some severely affected countries in Africa, the number of teachers dying of AIDS-related complications is higher than the number of new graduates produced by teacher-training colleges (Africa Renewal, 2007).

The demographic effects of the epidemic are significant, as it alters the population structure of hard-hit countries, affecting population growth and mortality rates and ultimately age and sex distributions. People die prematurely, during their most productive and reproductive years. One consequence of this is that fewer working-age people must support children

and the elderly. In parts of the world where women are disproportionately affected, HIV has changed the ratio of caregivers (mainly women) to those needing care.

Especially in sub-Saharan Africa, HIV is only one of several ongoing health crises, the most pressing being malaria, tuberculosis, pneumonia, and diseases of poor nutrition. These challenges are interrelated with HIV/AIDS, each intensifying and complicating the effects of the other. Abu-Raddad and colleagues (2006) found that repeated and transient increases in HIV viral load resulting from coinfection with malaria can amplify HIV prevalence, suggesting that malaria may be an important factor in the rapid spread of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa (see Chapter 6 for further discussion of this issue).

Poverty exacerbates all efforts to improve the well-being of populations, especially health. Often, there is a constellation of diseases that occur more consistently among the poor than among the more affluent. When health is viewed from a multiple-determinant model, such as that proposed by Evans and colleagues (Evans et al., 1994), it is clear that socioeconomic and physical environmental factors—including nutrition; housing; air, food, and water quality; waste disposal; injury control; infectious disease management; workplace and road safety; and issues concerning energy sources and use—play critical contributory roles in determining individual and population health outcomes, particularly in developing countries (Kindig, 1997). Poverty and environmental degradation are intricately linked, and their mutual reinforcement can have consequences that directly impact a country’s ability to meet the basic human needs (food, health, and education) of its population (UN, 2003b; Rice, 2006).

Capacity of Health Care Systems

An adequate health care infrastructure is critical to implementing efficient and effective HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment, and care programs. While this section focuses on the health sector, the Committee acknowledges that many other sectors, including education, agriculture, and transportation, also play a critical role in comprehensively addressing each country’s epidemic. Increasing demand for health care services is overwhelming the public health infrastructure in many developing countries. The health care system is central to surveillance, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of HIV/AIDS and related conditions. Some efforts have been made to build the capacity of health systems in developing countries, but donor support has not kept pace with the increasing demand for scale-up of the delivery of HIV/AIDS services (World Bank, 2006). Physical infrastructure, clinics, laboratories, the supply chain, and information systems all are stretched thin by the implementation of a national HIV/AIDS program.

On an operational level, the ability to implement programs effectively is often contingent on physical infrastructure, such as transportation routes, water and sanitation, schools, and other social resources. These elements of the health infrastructure are weakest in rural areas, where most people in the focus countries reside. Only about one-third of the population of the focus countries live in urban areas, although this varies widely among countries (U.S. DOS, 2006). Of the focus countries, Botswana and South Africa have the largest urban populations, documented at 54 percent and 53 percent, respectively; whereas Ethiopia and Uganda have the smallest—less than 15 percent in urban areas in both countries (UNAIDS, 2006).

The ability to procure HIV/AIDS drugs and supplies also affects the overall success of programs. Despite donor support, some existing procurement systems are fragile, lacking trained personnel, handicapped by antiquated technology, and limited in their forecasting ability. The capacity of smaller countries to negotiate successfully with manufacturers is also limited. Various procurement methods, including multicountry purchasing through organizations such as UNICEF, are currently in use. Group purchasing mechanisms are available through international partners, which supply many of the focus countries.

Capacity of the Health Care Workforce

Stephen Lewis, the UN Special Envoy for AIDS in Africa, remarked at the close of the 16th International AIDS Conference in 2006:

What has clearly emerged as the most difficult of issues, almost everywhere, certainly in Africa, is the loss of human capacity. In country after country, the response to the pandemic is sabotaged by the paucity of doctors, nurses, clinicians and community health workers. The shortages are overwhelming. Everyone is struggling. Most of the shortage stems from death and illness; some stems from brain-drain and poaching. But whatever the source, we have a problem of staggering dimensions.

The Institute of Medicine has previously reported that human resource capacity is very weak in resource-constrained settings, especially sub-Saharan Africa. Such limited capabilities pose a critical obstacle to providing access to antiretroviral therapy and prevention of mother-to-child transmission, particularly in rural settings (IOM, 2005). Policy makers and field staff in some of the most affected countries have identified the lack of human resources for health as the single most serious obstacle to scaling up treatment. The HIV/AIDS pandemic has exacerbated workforce shortages, as many countries lose large numbers of health care workers to AIDS. In some African countries, AIDS may be responsible for half of all deaths among employees in the public health sector.

Increasing Burden of HIV/AIDS on Women and Girls

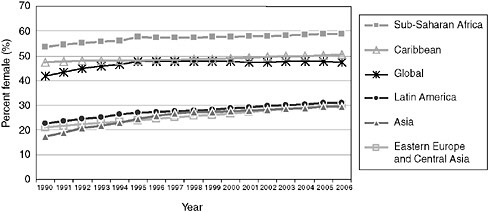

As of 2006, almost half of all people living worldwide with HIV/AIDS were women (UNAIDS, 2006). In sub-Saharan Africa, however, women now represent 59 percent of all people living with HIV/AIDS, and the proportion is growing (see Figure 2-2) (UNAIDS, 2006). Today’s statistics are the product of a trend toward increasing rates of infection among women, given that the pandemic started in men. The reasons underlying this trend include the inferior social and economic status of women in many countries, which affects their chances of gaining access to either means for prevention of or treatment for HIV/AIDS and related complications; violence against women and girls, including domestic, sexual, and war-related violence; and biological factors that increase the susceptibility of women to infection. UNAIDS has expressed concern about gender-based inequalities in access to treatment, with some evidence of women paying more for services and being hospitalized less frequently when clinically appropriate (UNAIDS, 2004b).

Teens and young adults (aged 15 to 24) continue to be at the center of the epidemic with heavy concentrations among those newly infected, accounting for more than 40 percent of new adult HIV infections in 2000. In sub-Saharan Africa, three young women are infected for every young man in this age group. The situation is similar in the Caribbean, where young women are about twice as likely as men their age to be infected with HIV (UNAIDS, 2006).

Biological characteristics place women at greater risk than men of contracting the virus from engaging in unprotected sex, but gender disparities

FIGURE 2-2 Percent of adults living with HIV who are female, 1990–2006.

SOURCE: Reprinted with the kind permission of UNAIDS, 2006.

and inequity are probably more responsible for rising infection rates in women. Even in the case of women who are married and engaging in intercourse only with their husbands, if their husbands have other sexual contacts, they are at increased risk of infection. For the past 5 years, HIV incidence has increased among married women and girls globally. In South Africa, infection rates have risen to more than 35 percent among pregnant women aged 25 to 29, and remain at more than 30 percent among pregnant women aged 30 to 34. At least in some places, women are aware of their vulnerability. In a 1999 national reproductive and child health survey in Tanzania, 62 percent of married women reported that they perceived the greatest risk factor for HIV infection to be their partners having other sexual contacts (National Bureau of Statistics Dar es Salaam, Tanzania and Macro International, 2000).

Most evidence suggests that women are at higher risk of infection from an infected male partner than vice versa. Although not entirely consistent, recent studies support an estimate that HIV is two to four times more transmissible to women than to men (NWHRC, 2006). Young girls whose reproductive systems are not fully developed are at even greater risk because of a higher propensity to develop microlesions and vaginal tearing, particularly in cases of sexual coercion (NWHRC, 2006). Women suffer from the same complications of AIDS that afflict men, but they also experience gender-specific manifestations of HIV infection that occur with less frequency or severity in HIV-negative women. These manifestations include recurrent vaginal yeast infections; severe pelvic inflammatory disease; and an increased risk of precancerous cervical lesions, which may indicate an increased risk of cervical cancer (NIAID/NIH, 2006).

Women are particularly vulnerable to HIV infection through heterosexual transmission because of substantial mucosal exposure to seminal fluids. This major biological factor of women’s susceptibility may be increased by the symptoms of sexually transmitted infections, especially those causing ulcerations of the vagina, such as genital herpes, syphilis, and chancroid, which increase the risk of transmission of HIV through sexual intercourse by two- to tenfold (Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, 2000; NIAID/NIH, 2006; NWHRC, 2006). Other infections can also increase a woman’s risk of contracting HIV. For example, although the specific bacteria involved have not been identified, bacterial vaginosis, the most prevalent vaginal infection in women of childbearing age, may double a woman’s susceptibility to HIV infection (Myer et al., 2005). The strategy of identifying and treating bacterial vaginosis has been proposed as a means of HIV prevention; however, the practicality of such an approach has yet to be demonstrated (Schwebke, 2005).

As the pandemic continues to take its toll on families and communities, the growing burden of caring for the sick, the dying, and those left behind

falls to women and girls. According to UNAIDS, most of the care for people living with HIV in the hardest-hit countries occurs at home, with up to 90 percent of such care being provided by women and girls (UNAIDS, 2006). According to UNAIDS, special attention should be paid to the difficulties women and children face as caregivers, including economic vulnerability due to widowhood and the lack of developmentally appropriate income-generating skills in the young, exacerbated by discrimination in property inheritance and employment. While they are caring for the sick and dying, they are also coping with the loss of their parents, siblings, other relatives, or adult children (UNAIDS, 2006). Elderly caregivers shoulder the additional concern of what will happen to the children for whom they are providing care when they themselves die. (See also the discussion of children and elderly women as caregivers below.)

Growing Numbers of Orphans and Other Vulnerable Children

The rising human cost of the pandemic can be measured not only by the rising toll of people losing their lives to the disease, but also by the escalating numbers of orphans and other vulnerable children. UNAIDS estimates that globally, more than 20 million children having lost at least one parent, will have been orphaned as a result of HIV/AIDS by 2010. This estimate does not include children who will have died (UNAIDS et al., 2002). In the 15 focus countries, the number of orphans due to all causes ranges from 33,000 in Guyana to an estimated 7 million in Nigeria (U.S. DOS, 2006). In 12 of the 15 focus countries, orphan populations due to all causes exceeding 500,000 have been reported (UNICEF, 2006a). Kenya, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda each have more than 1 million children orphaned because of AIDS. Namibia has reported the smallest population of children orphaned by AIDS in Africa, estimated at 85,000, which is slightly more than 4 percent of its total population of approximately 2 million people. No data are currently available for orphans due to AIDS for Ethiopia, Guyana, Haiti, and Vietnam (UNICEF, 2006a) (see Chapter 7). Estimates for children living with HIV/AIDS at the end of 2005 ranged from fewer than 1,000 in Guyana to 240,000 in both Nigeria and South Africa. Seven of the focus countries have reported more than 100,000 children living with HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS, 2006).

Attention to the needs of orphans and other vulnerable children is a critical element of a long-term HIV/AIDS strategy. While estimates of numbers of orphans do not include children made vulnerable by HIV/AIDS or any other health or social condition, they may well be the proverbial tip of the iceberg in terms of the visibility and extensive needs of children in these countries. These children become vulnerable not only to the risk of HIV infection, but also to a host of social and economic ills. Academic

performance may suffer or schooling may end prematurely because they must be caregivers or because family finances no longer allow them to be in school. The cascading effects of academic vulnerability often lead to economic vulnerability, including loss of income and/or property and lack of adequate shelter and food, which in turn may lead to increased risk of HIV exposure and infection through transactional or transgenerational sex in exchange for food, money, shelter, and other basic needs. Psychosocial vulnerability may develop from the need for emotional support due to HIV/AIDS from the individual child as well as the family and the burden of caregiving and guardianship for younger siblings. Survivor vulnerability may lead to poor nutrition, poor health, and lack of resources for basic care to meet the developmental needs of children. Finally, these children are vulnerable to exploitation and abuse when they have lost the protection of parents and the community (UNAIDS et al., 2004).

Children and Elderly Grandmothers as Caregivers

When young children (of any age up to 18) or elderly grandmothers are forced to head households, they face many challenges in terms of not only their ability to generate income, but also their own health and social service needs. Grandmothers are typically of the age at which physical labor, such as farming for subsistence or income generation, is difficult for them. They often need assistance themselves, even for chores such as carrying water and firewood. Many elderly grandmothers are concerned about what will happen to their grandchildren and other wards when they die. Succession planning and issues related to inheritance and property rights are crucial not only when the grandmothers die, but also during their caretaking years to ensure that there is a stable and physical environment in which the children can be raised and then assume caretaking responsibilities if they have no other extended family. Children whose parents have died or are too busy caring for a dying spouse or partner to pass on essential knowledge and skills (e.g., farming) are left behind their peers in preparing for adulthood (UNICEF, 2006b).

Elderly grandmothers and children are often framed as victims of the pandemic, but they appear to be forgotten in terms of their need for HIV/AIDS prevention information and education. Grandmothers are too often and incorrectly assumed to be sexually inactive, and children are not expected to engage in sex. If household and community safety nets fail, children are at risk for sexual and labor exploitation to meet their basic needs and thus are at risk for exposure to HIV. Children also have basic age-specific health needs for other common conditions (such as malaria and pneumonia), vaccinations against childhood diseases, and maintenance of hygienic conditions to prevent exposure to parasitic and other infections.

Children who are HIV-positive need a range of prevention, care, and treatment services (UNICEF, 2006b).

Stigma and Discrimination

Stigma and discrimination pose obstacles to responses to HIV/AIDS epidemics, but programs increasingly are addressing these issues and the challenges they present. Weiss and Ramakrishna (2001) make the point that for targeted strategies against stigma to be developed, the phenomenon needs to be better understood and measured. There is a need to understand the sociocultural context of stigma and its effects, to document its impact, to develop strategies needed to measure it, and to track its impact over time. While programs are focusing efforts on understanding and addressing stigma as well as monitoring these efforts, much of what has been reported about the effects of stigma and discrimination is anecdotal. That the effects are significant, however, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, is not doubted.

Stigma has been categorized for study as perceived, experienced, and internalized; and according to several domains—fear of casual transmission, values (shame, blame, and judgment), enacted stigma (discrimination), and disclosure (USAID, 2005). Common manifestations of stigma include social isolation or distancing in the community; family rejection; loss of respect; physical or verbal abuse or violence; expressed fear of casual transmission; feelings of shame and worthlessness for those infected with HIV and their family members; the experience of being blamed for contracting HIV; and denial of rights, education, employment, and health services. Moreover, health care workers may be stigmatized because they care for HIV patients (Project Siyam’kela, 2003; USAID, 2005). High levels of stigma have been associated with less willingness to care for a family member with HIV/AIDS (Letamo, 2003).

It has been reported that the availability of antiretroviral therapy has reduced the prevalence of AIDS-related stigma and resulted in increases in voluntary testing and counseling (Castro and Farmer, 2005); however, this phenomenon is not well documented. According to UNAIDS, reports from more than 30 countries indicate that stigma and discrimination against people with HIV remain pervasive (UNAIDS, 2006). Other researchers have reported that stigma has emerged as a major limiting factor in primary and secondary HIV/AIDS prevention and care by discouraging voluntary testing and counseling and care seeking, thus increasing suffering and shortening life (Weiss and Ramakrishna, 2001; Newman et al., 2002).

Few tested and validated indicators exist with which to measure stigma and efforts to reduce it (USAID, 2005). Stigma and its effects affect even the ability to gather HIV-related data. For example, individuals may misreport

(either way, in different circumstances) whether they have been tested (OGAC, 2005c) and certainly, if known, their HIV status. According to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), “current measures of stigma focusing on HIV/AIDS knowledge, fear of casual transmission, and social distancing often suffer from ambiguity and the inability to specify the underlying cause (motive) for the action” and are often presented with respect to hypothetical situations that may not accurately reflect people’s responses and actions in given situations (USAID, 2005, p. 5). Other difficulties associated with the study of stigma include very small samples that are not representative of the community or general population or large samples with few, ambiguous questions. One final challenge to understanding the complexity of stigma is the need to understand the motivation for such behavior in order to develop targeted interventions at the population level, including those to address “compound stigma,” defined as “HIV stigma that is layered on top of pre-existing stigmas, frequently toward homosexuals, commercial sex workers, injecting drug users, women, and youth” (USAID, 2005, p. 6).

Gaps in the Evidence Base

Planning and implementation of an integrated national HIV/AIDS program requires a reasonable base of evidence on the effectiveness and other characteristics of particular interventions and programs as applied in specific cultural, economic, and social contexts. However, significant gaps exist in understanding of the epidemic, how to best address it, and how to expand what is working. These gaps relate to every aspect of implementing an HIV/AIDS program, from precisely how HIV infections are spreading to how to assess clinical status without the capacity to measure viral load or CD4 (Bertozzi et al., 2006). As increasing amounts of HIV/AIDS funding are spent in the countries hardest hit by the pandemic, these gaps in the knowledge base will increasingly impair the ability of host countries and donors to achieve their HIV/AIDS control targets. Without this information, allocating the finite resources available is an even more difficult task (Grassly et al., 2001; Bollinger et al., 2004; Bertozzi et al., 2006).

A major research challenge in all areas is how to adapt strategies that originate mainly in wealthy countries to low-income, low-technology settings with low human resource capacity. As programs have been implemented, host countries, donors, and international organizations have been working to increase what is known about implementing a comprehensive HIV/AIDS program in a developing country (see, for example, the World Health Organization’s guidelines for antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings). But gaps in knowledge remain, and, as more is learned about combating HIV/AIDS in these settings, questions continue to arise.

THE PEPFAR FOCUS COUNTRIES

Funds from PEPFAR support HIV/AIDS relief in more than 120 countries, but two-thirds of the funds—$10 billion out of $15 billion over 5 years—is to be spent on the development of comprehensive and integrated prevention, treatment, and care programs in the 15 focus countries (OGAC, 2004, 2005b). PEPFAR has established 5-year targets for its prevention, treatment, and care programs in these countries to support prevention of 7 million new HIV infections; treatment of 2 million HIV-infected people with antiretroviral therapy; and care for 10 million people infected and affected by HIV/AIDS, including orphans and other vulnerable children.3

Among the 12 PEPFAR focus countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the adequacy of the health workforce varies considerably. For example, the average doctor-to-population ratio is 22 per 100,000 among the focus countries. Only South Africa and Vietnam report more than 50 doctors per 100,000; Ethiopia, Mozambique, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda report 5 or fewer. (By comparison, the United States has 256 physicians per 100,000 population.) Similar disparities exist for other types of health care workers (see Table 2-3).

The focus countries are among those nations with the lowest per capita incomes in the world, but important variations exist in their gross domestic product and unemployment rates (see Table 2-4). The average gross domestic product per capita for the 15 focus countries at the end of 2005 was approximately US$3,003 (UNAIDS, 2006). Among the focus countries, Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa have gross domestic products per capita greater than US$5,000. At US$10,960, South Africa has the highest per capita gross domestic product (CIA, 2006) At the other end of the spectrum, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Zambia have gross domestic products per capita of less than US$1,000. Tanzania has the lowest of all, at US$660 (UNAIDS, 2006). The World Bank has classified 9 of the focus countries—Ethiopia, Guyana, Mozambique, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Côte d’Ivoire, and Haiti—as “heavily indebted poor countries.” In 3 focus countries, half of the population lives on less than US$1 per day; in Nigeria, the proportion is 70 percent (UNDP, 2005). Unemployment rates in the focus countries are highly variable. Five have unemployment rates below 10 percent, with Nigeria having the lowest at 3 percent (World Bank, 2006). In contrast, Kenya, Namibia, South Africa, and Zambia all report unemployment rates higher than 25 percent. Zambia’s is highest, at 50 percent (World Bank, 2006).

The focus countries all are generally experiencing devastating HIV/

TABLE 2-3 Density of Selected Health Care Workers in the PEPFAR Focus Countries

|

Country (year represented by data) |

Health Care Workers (Total)a |

Physicians |

Nurses |

Midwives |

Other Health Workers |

Medical Assistants |

Community Health Workers |

|||||

|

Total |

Density Per 1000 |

Total |

Density Per 1000 |

Total |

Density Per 1000 |

Total |

Density Per 1000 |

(Total)c |

Total |

Density Per 1000 |

||

|

United States (2002) |

15,959,391 |

730,801 |

2.56 |

2,669,603 |

9.37 |

N/A |

N/A |

4,177,609 |

14.66 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Botswana (2004) |

7,117 |

715 |

0.40 |

4,753 |

2.65 |

N/A |

N/A |

829 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Côte d’Ivoire (2004) |

17,214 |

2,081 |

0.12 |

7,773 |

0.60 |

2,407 |

N/A |

147 |

0.01 |

25 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Ethiopia (2003) |

48,972 |

1,936 |

0.03 |

14,270 |

0.21 |

1,274 |

0.01 |

43 |

0.10 |

7,311 |

13,433 |

0.26 |

|

Guyana (2000) |

2,134 |

366 |

0.48 |

1,738 |

2.29 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Haiti (1998) |

2,877 |

1,949 |

0.25 |

834 |

0.11 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Kenya (2002/04) |

66,956 |

4,506b |

0.14 |

37,113b |

1.14 |

N/A |

N/A |

5,610 |

0.17 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Mozambique (2004) |

20,129 |

514 |

0.03 |

3,947 |

0.21 |

2,236 |

0.12 |

1,225 |

0.09 |

434 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Namibia (2004) |

16,244 |

598 |

0.30 |

6,145 |

3.06 |

N/A |

N/A |

597 |

0.30 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Nigeria (2003/04) |

371,726 |

34,923b |

0.28 |

127,580b |

1.70 |

82,726b |

N/A |

1,220 |

0.01 |

N/A |

115,761 |

0.91 |

|

Country (year represented by data) |

Health Care Workers (Total)a |

Physicians |

Nurses |

Midwives |

Other Health Workers |

Medical Assistants |

Community Health Workers |

|||||

|

Total |

Density Per 1000 |

Total |

Density Per 1000 |

Total |

Density Per 1000 |

Total |

Density Per 1000 |

(Total)c |

Total |

Density Per 1000 |

||

|

Rwanda (2004) |

18,427 |

401 |

0.05 |

3,570 |

0.42 |

77 |

0.01 |

446 |

0.06 |

75 |

12,557 |

1.41 |

|

South Africa (2004) |

319,992 |

34,829 |

0.77 |

184,459 |

4.08 |

N/A |

N/A |

40,479 |

0.90 |

13 |

14,306 |

0.20 |

|

Tanzania (2002) |

48,508 |

822 |

0.02 |

13,292 |

0.37 |

N/A |

N/A |

3,755 |

0.82 |

25,967 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Uganda (2004) |

35,445 |

2,209 |

0.08 |

15,161 |

0.61 |

4,164 |

0.12 |

3,772 |

0.14 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Vietnam (2001) |

107,505 |

42,327 |

0.53 |

44,539 |

0.56 |

14,662 |

0.19 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Zambia (2004) |

41,429 |

1,264 |

0.12 |

16,990 |

1.74 |

5,020 |

0.27 |

3,330 |

0.30 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

NOTE: N/A = Data not available. aEstimated number of total health care workers in each country including physicians, nurses, midwives, dentists, pharmacists, public and environmental health workers, community health workers, laboratory technicians, other health care workers, and health management and support workers. bThe data provided is only for the year 2004. cThe numbers provided for Medical Assistants are the total of assistants in each country. No density rates are available for this category of worker. SOURCE: Compiled from data from WHO, 2006b. |

||||||||||||

TABLE 2-4 Selected Economic and Health-Related Indicators of the PEPFAR Focus Countries

|

Country |

Populationa |

Income Statusb |

GDP per Capita (US$)a |

Life Expectancyc |

Adult HIV/AIDS Prevalence [Range] (ages 15–49)a |

Infant Mortality Rate (deaths/1,000 live births)d |

|

|

Botswana |

1,765,000 |

Upper middle |

8,920 |

35 |

24.1 |

[23.0–32.0] |

54.58 |

|

Côte D’Ivoire |

18,154,000 |

Low |

1,390 |

47 |

7.1 |

[4.3–9.7] |

90.83 |

|

Ethiopia |

77,431,000 |

Low |

810 |

48 |

|

[0.9–3.5] |

95.32 |

|

Guyana |

751,000 |

Lower middle |

4,110 |

63 |

2.4 |

[1.0–4.9] |

33.26 |

|

Haiti |

8,528,000 |

Low |

1,680 |

52 |

3.8 |

[2.2–5.4] |

73.45 |

|

Kenya |

34,256,000 |

Low |

1,050 |

47 |

6.1 |

[5.2–7.0] |

61.47 |

|

Mozambique |

19,792,000 |

Low |

1,160 |

42 |

16.1 |

[12.5–20.0] |

130.79 |

|

Namibia |

2,031,000 |

Lower middle |

6,960 |

46 |

19.6 |

[8.6–31.7] |

48.98 |

|

Nigeria |

131,530,000 |

Low |

930 |

44 |

3.9 |

[2.3–5.6] |

98.80 |

|

Rwanda |

9,038,000 |

Low |

1,300 |

44 |

3.1 |

[2.9–3.2] |

91.23 |

|

South Africa |

47,432,000 |

Upper middle |

10,960 |

52 |

18.8 |

[16.8–20.7] |

61.81 |

|

Tanzania |

38,329,000 |

Low |

660 |

44 |

6.5 |

[5.8–7.2] |

98.54 |

|

Uganda |

28,816,000 |

Low |

1,520 |

48 |

6.7 |

[5.7–7.6] |

67.83 |

|

Vietnam |

84,238,000 |

Low |

2,700 |

72 |

0.5 |

[0.3–0.9] |

25.95 |

|

Zambia |

11,668,000 |

Low |

890 |

37 |

17.0 |

[15.9–18.1] |

88.29 |

|

NOTE: GDP = gross domestic product. aUNAIDS, 2006. bWorld Bank, 2006. cPRB, 2005. dCIA, 2006. SOURCE: Compiled from data from CIA, 2006; PRB, 2005; UNAIDS, 2006; World Bank, 2006. |

|||||||

AIDS epidemics, but the specifics vary considerably by country. With reference to the classification of country-level epidemics in Table 2-1, except for Vietnam, the HIV/AIDS epidemic is generalized in all of the focus countries, with unprotected heterosexual intercourse remaining the most prevalent mode of HIV transmission and people at risk spanning all age groups and both sexes (UNAIDS, 2006). Adult prevalence is above 5 percent in Botswana, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia (UNAIDS, 2006). Adult prevalence is below 5 percent in Ethiopia, Guyana, Haiti, Nigeria, Rwanda, and Vietnam (UNAIDS, 2006). Vietnam is the only PEPFAR focus country whose epidemic is characterized as concentrated, with the lowest reported adult HIV prevalence rate of the focus countries at 0.5 percent (UNAIDS, 2006).

Underlying the common classification of generalized epidemic are 14 distinct epidemics occurring in 14 unique contexts. PEPFAR will succeed in reaching its stated targets only if programs are tailored to differences in the state of the epidemics, demographics, political and economic situations, health systems, and social structure (specifically regarding gender and equality). For example, differences in infrastructure affect drug delivery, a critical component of PEPFAR’s treatment arm. Each country has a different array of internal systems and external partners, which require coordination and communication. Physical infrastructure and human resource capacity also vary from country to country.

PEPFAR’S AUTHORIZING LEGISLATION: THE LEADERSHIP ACT

In early 2001, at the start of the 107th session of the U.S. Congress, two seminal bills were introduced in the Senate. The first, known as the International Infectious Diseases Control Act of 2001 (S.1032), called for an increase in funding of $200 million for the prevention of HIV transmission from mother to child (along with other provisions) through the establishment of a Global Fund to Fight Against HIV/AIDS, Malaria and Tuberculosis.4 The second was the Kerry-Frist Global AIDS bill (S.15), formally known as the U.S. Leadership against HIV/AIDS, TB and Malaria Act of 2002. This latter bill was the first coordinated effort by U.S. leadership to respond to the global AIDS pandemic.5 Although neither of these bills was

|

4 |

S.1032IS, International Infectious Diseases Control Act of 2002, accessed from http://thomas.loc.gov on September 11, 2006. |

|

5 |

Presentations by Allen Moore (former deputy chief of staff and policy director for Senator Bill Frist) and Dr. Nancy Stetson (senior foreign policy advisor to Senator John Kerry) to the Institute of Medicine’s PEPFAR Evaluation Committee’s Open Meeting, September 15, 2005, in Washington, DC. |

passed, elements of both were incorporated into what would become the Leadership Act that authorized PEPFAR.6

On January 28, 2003, President Bush delivered his State of the Union address, in which he proposed a 5-year, $15 billion initiative to treat and prevent HIV/AIDS in some of the world’s most affected countries. Legislation to enact this initiative was introduced in the House of Representatives on March 17, 2003, and in the Senate on May 7, 2003. Many amendments were introduced and debated, a few of which, related mainly to the focus countries, substantively changed the legislation. One amendment established priorities for the “distribution of resources based on factors such as the size and demographic characteristics of populations affected by HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria; the needs of that population; and the existing infrastructure or funding levels to cure, treat, and prevent HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria” (P.L. 108-25, §101). A further provision called for “[the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] in coordination with the Global [AIDS] Coordinator, [the National Institutes of Health, the World Health Organization], UNICEF, and national governments to develop and implement effective strategies to improve injection safety, including eliminating unnecessary injections, promoting sterile injection practices and technologies, strengthening the procedures for proper needle and syringe disposal, and improving the education and information provided to the public and to health professionals” (P.L. 108-25, §306).

Another amendment required “assistance for the purpose of encouraging men to be responsible in their sexual behavior, child rearing, and to respect women” (P.L. 108-25, §301, §104(d)(1)(c)). The next created a pilot program of assistance for children and families affected by HIV/AIDS to “ensure the importance of inheritance rights of women, particularly women in African countries, due to the exponential growth in the number of young widows, orphaned girls, and grandmothers becoming heads of households as a result of the HIV/AIDS pandemic” (P.L. 108-25, §314(b)(4)). An additional amendment required not less than 10 percent of appropriated PEPFAR funds to be allocated to programs that would serve orphans and other vulnerable children affected by HIV/AIDS, at least half of this 10 percent allotment being provided through nonprofit, nongovernmental organizations, including faith-based organizations, that would implement programs on the community level (P.L. 108-25, § 403(b)).

Several amendments added features to the legislation that have been the subject of ongoing debate. For example, the Leadership Act underscores the importance of involving faith-based organizations in the initiative and also exempts them from participating in activities to which they hold

|

6 |

S.1099, United States Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief Act of 2003 and HR 1298, United States Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief Act of 2003, accessed from http://thomas.loc.gov on September 11, 2006. |

religious or moral objection. The legislation states that “an organization that is otherwise eligible to receive assistance … to prevent, treat, or monitor HIV/AIDS shall not be required, as a condition of receiving the assistance, to endorse or utilize a multisectoral approach to combating HIV/AIDS, or to endorse, utilize, or participate in a prevention method or treatment program to which the organization has a religious or moral objection” (P.L. 108-25, p. 733). Further, the legislation states that “no funds made available to carry out this Act, or any amendment made by this Act, may be used to promote or advocate the legalization or practice of prostitution or sex trafficking. Nothing in the preceding sentence shall be construed to preclude the provision to individuals of palliative care, treatment, or postexposure pharmaceutical prophylaxis, and necessary pharmaceuticals and commodities, including test kits, condoms, and, when proven effective, microbicides. No funds made available to carry out this Act, or any amendment made by the Act, may be used to provide assistance to any group or organization that does not have a policy explicitly opposing prostitution and sex trafficking” (P.L. 108-25, pp. 733–734). Finally, the legislation required that of the amounts appropriated, “an effective distribution of such amounts would be 20 percent of such amounts for HIV/AIDS prevention … of which such amount at least 33 percent should be expended for abstinence-until-marriage programs” (P.L. 108-25, p. 746).

Congress passed the Leadership Act, and on May 27, 2003, the President signed it to become P.L. 108-25, The United States Leadership against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Act of 2003. The Leadership Act called for bold leadership by the United States in international HIV/AIDS programs; however, it stressed the overarching need to coordinate with local, national, and international partners. In particular, the act recognized that the new resources being provided could not meet all needs, and it sought to complement existing programs that might already be meeting some needs. The legislation stated that the Global AIDS Coordinator would collaborate and coordinate with civil sector organizations to plan, fund, implement, monitor, and evaluate all programs addressing HIV/AIDS.

Requirement for a Comprehensive 5-Year Strategy

The Leadership Act directed the President to submit a strategy meeting specified objectives (see Box 2-5) to the Committee on Foreign Relations of the Senate and the Committee on International Relations of the House of Representatives, the committees with jurisdiction over the legislation.

Specification of Focus Countries

The PEPFAR legislation named 14 focus countries, which at the time accounted for more than half of the world’s HIV/AIDS cases. These 14

|

BOX 2-5 Central Objectives of P.L. 108-25 for Strategy Development

SOURCE: P.L. 108-25. |

countries—12 in Africa and 2 in the Caribbean—had been named by President Bush in his 2003 State of the Union address. The law gave the President the authority to add focus countries, which he did, adding a 15th—Vietnam—in June 2004. The focus countries are the Republic of Botswana (Botswana), the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire (Côte d’Ivoire), the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (Ethiopia), the Cooperative Republic of Guyana (Guyana), the Republic of Haiti (Haiti), the Republic of Kenya (Kenya), the Republic of Mozambique (Mozambique), the Republic of Namibia (Namibia), the Federal Republic of Nigeria (Nigeria), the Republic of Rwanda (Rwanda), the Republic of South Africa (South Africa), the United Republic of Tanzania (Tanzania), the Republic of Uganda (Uganda), the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (Vietnam), and the Republic of Zambia (Zambia). The goal of concentrating the majority of the PEPFAR funds in selected focus countries is to scale up rapidly to have impact on their epidemics at the national level.

The U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator

The legislation established the position of a U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator to be appointed by the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate. The Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator (OGAC) was established within the Department of State. The Coordinator, who reports directly to the Secretary of State, has primary responsibility for oversight and coordination of all resources for the U.S. government’s international activities to combat the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

Reporting Requirements

In addition to other reports, the Leadership Act required the President to deliver annual reports to the committees with jurisdiction to describe progress, in particular to assess the impact of the program in reducing the spread of HIV/AIDS (particularly among women and girls and through mother-to-child transmission) and in

-

Providing treatment for HIV/AIDS

-

Improving health delivery systems

-

Treating and curing people with tuberculosis and malaria

As required, three annual reports have been submitted to date. The first, entitled Engendering Bold Leadership; the second, entitled Action Today: A Foundation for Tomorrow; and the third, entitled The Power of Partnerships; covered fiscal years 2004, 2005, and 2006, respectively (OGAC, 2005b, 2006a, 2007b). Many other reports have been submitted in response to requests on specific topics. In 2006, for example, OGAC

submitted reports on workforce capacity, food and nutrition, supplying antiretrovirals, primary and secondary education for children, and refugees and internally displaced persons (OGAC, 2006b–f).

Performance Targets

The Leadership Act did not provide a rationale for the derivation of the performance targets for prevention, treatment, and care. However, the Committee did learn at one of its public meetings that the prevention target represented roughly half of the expected new infections in the focus countries (Dybul, 2005). The Committee also learned that a group of economists with UNAIDS was consulted to help derive the targets (personal communication, Stefano Bertozzi).

Budget Allocations

The Leadership Act specified several budget allocations that were originally intended as guidance for the first 2 years of the legislation, but many became mandatory beginning in fiscal year 2006. They include the following:

-

55 percent for “therapeutic medical care of individuals infected with HIV, of which such amount at least 75 percent should be expended for the purchase and distribution of antiretroviral pharmaceuticals and at least 25 percent should be expended for related care”

-

20 percent for “HIV/AIDS prevention, of which such amount at least 33 percent should be expended for abstinence-until-marriage programs”

-

15 percent for “palliative care of individuals with HIV/AIDS”

-

Not less than 10 percent for “assistance for orphans and vulnerable children affected by HIV/AIDS, of which such amount at least 50 percent shall be provided through non-profit, nongovernmental organizations, including faith-based organizations, that implement programs on the community level”

THE 5-YEAR STRATEGY: THE PRESIDENT’S EMERGENCY PLAN FOR AIDS RELIEF

The Leadership Act required development of a comprehensive 5-year strategy, guided by the legislation (Box 2-3). The strategy (which includes elements cited in Box 2-4) was developed and presented to Congress by Ambassador Tobias, the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, on February 23, 2004, 9 months after the act had been signed into law. The Ambassador stressed that the strategy should be viewed as a “work in progress,” something that

could change in response to changes in the HIV/AIDS pandemic and the knowledge and tools available. The strategy has four main emphases: (1) rapidly expanding services, building on existing successful programs; (2) identifying new partners and building capacity for sustainable, effective, and widespread HIV/AIDS responses; (3) encouraging bold leadership and fostering a sound enabling policy environment for combating HIV/AIDS and mitigating its consequences; and (4) implementing strong strategic information systems that will contribute to continued learning and identification of best practices.

The strategy also stresses collaboration and coordination with a wide range of partners, including relevant parts of the U.S. government, nongovernmental organizations of all types, the private sector, and international organizations. Responsiveness to local needs as well as to national priorities and strategies is also key (OGAC, 2004).

As required, the strategy assigns priorities for and allocates resources to relevant executive branch agencies, including the Departments of State, Defense, Commerce, Labor, Health and Human Services (specifically, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and Health Resources Services Administration), the U.S. Agency for International Development, and the Peace Corps. Most of these agencies were already involved in global HIV/AIDS efforts prior to PEPFAR (OGAC, 2004) (see Box 2-6).

The PEPFAR strategy is responsive to legislative imperatives while containing the major elements of an HIV/AIDS strategy recommended by normative entities such as the World Health Organization and UNAIDS.

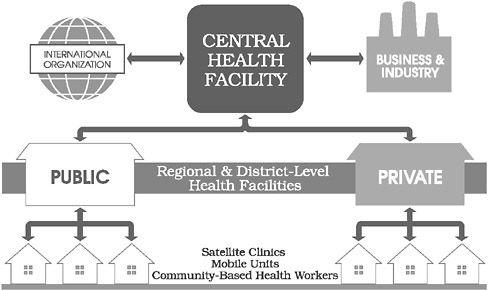

The Network Model

PEPFAR’s 5-year strategy describes a network model developed to deliver prevention, treatment, and care services for HIV/AIDS, consistent with the priorities and requirements of the Leadership Act. The basic design, adopted from a successfully implemented model in Uganda, relies on centralized, core facilities (staffed by different practitioners of varying skill) from which technical support and products flow to facilities in the periphery, especially to rural and underserved areas. In turn, facilities and staff at different points in the network identify and refer people needing more complex care to the more advanced central facilities (OGAC, 2004) (see Figure 2-3).

The model relies on existing medical facilities, such as district-level hospitals and local health clinics, for basic services. Private—often faith-based—medical facilities are relied upon to rapidly scale up existing palliative care services for adults and children with AIDS, with the aim of ensuring long-term sustainability. Finally, information systems are to be set

|

BOX 2-6 HIV/AIDS Activities of U.S. Government Agencies Implementing PEPFAR Department of State:

Department of Health and Human Services:

Department of Defense:

Department of Labor:

U.S. Agency for International Development:

Peace Corps:

SOURCE: OGAC, 2004. |

FIGURE 2-3 PEPFAR’s network model.

SOURCE: OGAC, 2004.

up to monitor progress and ensure that programs comply with PEPFAR’s stated policies and strategies (OGAC, 2004, 2006g). The network model envisions information systems in facilities at all levels, with links and regular feedback loops to provide information to health providers and policy makers (OGAC, 2006g). Recognizing the severe shortages of health care personnel in focus countries, the model includes training for community health workers to deliver routine care, manage symptoms, and monitor for treatment adherence.

The description of the network model focuses on medical services, with less attention to social services. The model states the intent to use and strengthen linkages among the levels of support, but does not explain how this will be accomplished. Home-based services, largely for palliative care, are acknowledged as important and cost-effective, but are otherwise not elaborated upon.

Organizational Structure

The U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator

The first U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, Randall Tobias, was sworn in with the rank of Ambassador on October 6, 2003; on February 23, 2004, he presented to Congress the U.S. 5-year global HIV/AIDS strategy. The Coordinator’s office, OGAC, is responsible for maintaining the focus of

PEPFAR by leading policy development, program oversight, and coordination both among U.S. government departments and agencies and with other donors and governments (Box 2-5). The Coordinator is responsible for the allocation of funds that are distributed through the U.S. government departments and agencies cited earlier.

Coordination and Support Within the Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator

Within OGAC, staff are organized into several groups, all of which include OGAC staff and representatives from the other U.S. government departments and agencies coordinated by OGAC (Table 2-5). These groups include the Policy Group, incorporating representation from the U.S. Agency for International Development, the Department of Health and Human Services, the White House, and the National Security Council; the Deputy Principals Group, handling program management and logistics, with representation from the majority of the government department and agencies cited above; and a Scientific Steering Committee, consisting of representatives from the two largest of the above implementing departments and agencies and the Department of Defense (Moloney-Kitts, 2005). Finally, Core and Technical Teams, which draw members from a wide range of U.S. government agencies, are responsible for supporting programs in PEPFAR countries in addressing specific technical and implementation issues.

PEPFAR Focus Country Teams

Each focus country has a U.S. Government Country Team that is responsible for coordinating PEPFAR-sponsored programs in the country. The Country Team is led by the U.S. ambassador to the country and includes representatives from all of the implementing departments and agencies. The staff of Country Teams serve in foreign-service posts. The Committee observed that the teams varied in size, expertise, and length of time served in the country.

The Country Team is supported by a core team at OGAC headquarters. Often, an ambassadorial steering committee works with the in-country team and the minister of health on HIV/AIDS efforts (in some countries this committee also serves as the Country Coordinating Mechanism for the Global Fund) (OGAC, 2005a).

Funding

The Leadership Act authorized $15 billion, including about $10 billion in new resources, for efforts to combat global HIV/AIDS. The majority of the funding is intended to be concentrated in the 15 focus countries.

TABLE 2-5 Structure for Coordination and Support Within the Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator

|

Group |

Responsibility |

Involved Agencies |

|

Ambassador |

Leadership of Initiative

|

U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, Ambassadors |

|

Agency Principals |

Policy |

Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, U.S. Agency for International Development, Department of Health and Human Services, National Security Council, White House |

|

Deputy Principals |

Management/Programs

|

Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, U.S. Agency for International Development, Department of Health and Human Services, Peace Corps, Department of Defense, Department of Labor |

|

Scientific Steering Committee |

Scientific Integrity

|

Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, U.S. Agency for International Development, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Defense |

|

Core Teams |

General Field Support

|

Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, U.S. Agency for International Development, Department of Health and Human Services, Peace Corps, Department of Defense, Department of State |

|

Technical Working Groups |

Technical Assistance and Review to Support the Field

|

Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, U.S. Agency for International Development, Department of Health and Human Services, Peace Corps, Department of Defense, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Agriculture |

|

SOURCE: Moloney-Kitts, 2005. |

||