6

Establishing an Evidence-Based Framework

OVERVIEW

The Committee’s review of Congress’ and the Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA’s) approach to establishing presumptions has identified multiple elements of the process for reconsideration. In the next four chapters, the Committee develops a conceptual foundation for implementing an evidence-based system for compensation and offers recommendations for future approaches in Chapter 12. This chapter serves as an introduction to this section of the report, offering general considerations on the basis for making presumptions and their role in compensation by VA.

There are two ideas that underpin these four chapters:

-

Decisions about presumptions should be grounded in a scientific evaluation of the full range of evidence that the exposure of interest causes the disease or disability.

-

If there is sufficient evidence to infer a causal relationship, the amount of disease attributable to the exposure should be estimated.

Chapters 7 and 8 address the first question of whether a causal relationship exists. Chapter 7 makes explicit what is meant by cause in contrast to statistical association and details the sources of evidence necessary to reach a conclusion as to whether there is a causal relationship. Chapter 8 then discusses quantitative and qualitative approaches for integrating epidemiological, laboratory, and other kinds of evidence to reach conclusions about the strength of evidence for association and causation. This background

provides a foundation for the Committee’s specific recommendations in Chapter 12, which outlines a classification system for characterizing the strength of evidence in support of a general causal relationship. Assuming that such a causal relationship has been established, Chapter 9 discusses how to quantify the strength of the causal effect, using measures most relevant to compensation decisions under the presumptive process: the attributable fraction for the population of exposed veterans, and the probability of causation for an individual. Chapter 10 covers the various types of data necessary to assess the existence of a causal relationship and to quantify the size of the causal effect. It proposes future comprehensive exposure and health data collection strategies for military personnel and veterans.

Provision of compensation to a veteran, or to any other individual who has been injured, on a presumptive basis requires a general decision as to whether the agent or exposure of concern has the potential to cause the condition or disease for which compensation is to be provided, in at least some individuals, and a specific decision as to whether the agent or exposure has caused the condition or disease in the particular individual or group of individuals. The determination of causation for veterans is based on review and evaluation of all relevant evidence including (1) measurements and estimates of exposures of military personnel during their service, if available; (2) direct evidence on risks for disease in relation to exposure from epidemiologic studies of military personnel; (3) other relevant evidence, including findings from epidemiologic studies of nonmilitary populations who have had exposure to the agent of interest or to similar agents; and (4) findings relevant to plausibility from experimental and laboratory research. Scientists and scientific organizations, such as the Institute of Medicine (IOM), have developed approaches for reviewing evidence and determining if causation can be inferred. Typically, these approaches involve a comprehensive review and the judgment of a panel of experts as to whether the evidence supports causation and with what degree of strength. The determination of causation for a particular veteran is based first on the general determination as to whether the exposure causes disease, and then on information on the exposures and possibly on clinical features of the individual being evaluated for compensation.

Compensation decisions critically depend on determinations of cause, but the information available for determining general or specific causation may be incomplete or inconclusive. For a group, the evidence may be insufficient or still evolving, and for an individual, information on exposure may be lacking, or there may be uncertainty as to the role of service-related factors versus the roles of other factors in causation. In the Agent Orange example, information on cancer risk in exposed veterans was not available until they had been followed for a sufficient time, reflective of the latency

between exposure and disease risk for carcinogens. For individual Vietnam veterans, exposure to Agent Orange cannot be estimated with any certainty, and VA has made a presumption with regard to exposure of Vietnam veterans to Agent Orange (VA, 2002). VA has also presumptively linked certain outcomes, such as prostate cancer and type 2 diabetes, based on evidence for association to Agent Orange exposure. By contrast, presumptions are not needed for combat-related casualties for which there is no uncertainty as to causation.

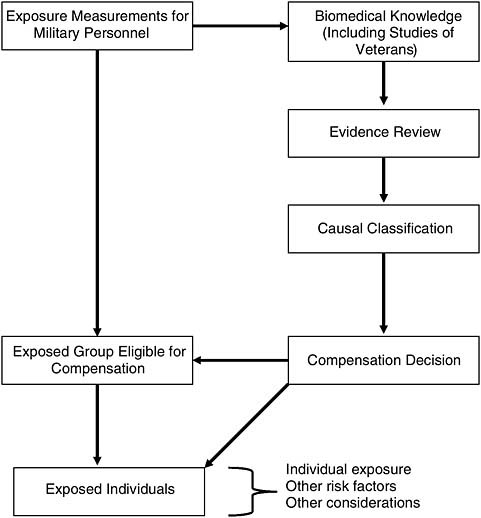

The role of presumptions becomes evident when the complete suite of information needed by VA for making compensation decisions for groups and for particular individuals is considered. Figure 6-1 describes information gathering and how information may be used for making general and specific judgments about causation and for making evidence-based decisions with regard to compensation. The schema in the figure assumes that the availability of information for making these determinations, as well as the roles of factors beyond the scientific evidence, such as costs and political considerations, are all figured into the process. Presumptions are made when there are gaps in the information related to exposure and causal classification. Factors other than the evidence relevant to the causal classification may affect the compensation decision.

If complete information were available, the process in the table could flow without presumptions, but the review of presumptions in Chapter 2 shows that this ideal has been infrequent and many presumptions have been made. The military workplace and particularly combat can lead to many exposures that may affect future health status and disease occurrence. Military personnel sustain a variety of exposures, some specific to the military and others not, that may increase risk for disease. If exposures of potential concern were tracked during military service and disease surveillance were in place and maintained, even for those who have left active duty, evidence could be generated directly relevant to the causation of disease in veterans. Disease rates could be compared in exposed and nonexposed veterans, for example. Lacking such evidence, reviewing groups turn to epidemiologic studies of other populations and gauge the relevance of the findings for the exposures of veterans. Such groups also give consideration to toxicological and other research information. For a specific individual, the determination of eligibility for compensation would be based ideally in full knowledge of that individual’s risk and an estimation of his or her probability of causation, given exposure history and observational information on the associated risk from similarly exposed people. However, this level of information and scientific understanding has not yet been fully achieved for individual causation for any agent.

FIGURE 6-1 Information gathering and its use in making general and specific compensation decisions.

A FRAMEWORK FOR PRESUMPTIONS

For all veterans or a particular group of veterans, the evidence may be sufficient to identify a causal relationship between an exposure and a health outcome. However, certainty as to whether an individual veteran’s service caused his or her disability or illness will vary depending on clinical characteristics and the availability of information on the veteran’s exposures during service.

In decisions to award compensation, two types of errors may occur: giving compensation to a veteran whose illness was not caused by the service-related factor (false positive) and denying compensation to a veteran whose illness was caused by the factor (false negative). These two types of errors need consideration in the design of compensation schemes.

This section establishes a framework for reasoning about compensation for service-attributable disability and illness and for making presumptions, and discusses the concept of a disability or illness being service attributable—that is, caused by a veteran’s service. (A more detailed discussion of models of causation is presented in Chapter 8 and Appendix J.) This section also describes the types of errors that can be made and the potential costs of each. It then addresses presumptions, viewed as one approach to completing gaps in the evidence needed for making decisions about compensation. The Committee emphasizes the need to address the false positive and false negative rates of particular decisions.

To simplify this chapter, the Committee considers the onset of a particular definable disease, a dichotomous outcome. Of course, some diseases are non-specific in their characteristics and the extent of disability associated with a particular disease may be a continuum from mild to very severe.

Service-Attributable Disease

In the circumstance that a veteran has a specific medical disease, the primary question for presumptive compensation is whether the disease is attributable, that is, caused by exposures during military service. We ask whether, absent service, the disease would have occurred at all or would have been less severe. The answer for any particular veteran can never be known exactly because it is not possible to observe the same person as exposed and non-exposed. The needed comparison for what would have happened to the exposed person, had they not been exposed, is referred to as the “counterfactual”—in other words, counter to the actual facts. We use information from unexposed but similar persons to describe the counterfactual. For example, the rate of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in former prisoners of war (POWs) could be compared to the rate in veterans with combat service who had not been POWs. There is an implicit assumption that the rate in non-POWs represents the rate in POWs, had they not been POWs. The excess in the POWs reflects the contribution of having been a POW.

The degree of certainty as to whether a disease is caused by service will vary substantially across different exposures and diseases. At one extreme, if the health problem is the direct result of an event during service, such as a battle wound, then full service attribution can be made with certainty. For chronic diseases with multiple causes there may be much less certainty. For example,

consider a Vietnam veteran who develops diabetes. His service has been established as a potential risk factor based on findings of epidemiologic studies and knowledge that some Vietnam veterans were exposed to Agent Orange, leading to a presumption of exposure of all Vietnam veterans. However, other factors, such as obesity and age, also contribute to the development of diabetes. Service attribution for diabetes in this particular veteran is much more uncertain than for disability from the battle wound. The uncertainty comes both from gaps in the general evidence linking Agent Orange to diabetes and from limitations of the information available on exposure and other relevant characteristics for the particular veteran.

In deciding whether to compensate a group of veterans on a presumptive basis, review is needed of all relevant data to assess if the disease is service attributable, including information about wartime exposures and other risk factors (such as obesity, age, and gender, in the example of diabetes). This information would then be used to estimate the likelihood, that is, the chance that exposure during military service contributed to the disease in the group. Currently, with the exception of radiation for which quantitative risk approaches are available, VA takes a more qualitative approach to determining service attribution, while using information about the exposure and other factors, as available. For some diseases of current concern with several causes, the causal agents contributing in a particular individual cannot be known with certainty so that presumptions will lead to false positive and negative errors.

Errors

The two possible errors that can be made in deciding service attribution (assuming knowledge of whether or not a veteran’s disease was caused by exposures during service) are summarized in Table 6-1. A false positive decision is made when the veteran’s disease is not caused by his or her service, but VA decides that it was. A false negative decision is made when the disease is caused by service, but VA does not determine it to be service attributable.

The rates of correct decisions are called the sensitivity or true positive rate (TPR) and the specificity or the true negative rate (TNR). In other words, the proportion of all truly service caused cases that are correctly classified as service attributable is called sensitivity, whereas the proportion of all truly non-service caused cases that are correctly judged not to be service attributable is called specificity. Sensitivity is the probability of correctly deciding that a person’s disease was caused by service. Specificity is the probability of correctly deciding that it was not.

The example above addresses the correct classification of veterans with regard to the causation of disease by exposures during military service. The

TABLE 6-1 Possible Decisions About Service-Attributable Diseases (SADs) with Associated Errors and Losses

|

Decision |

Truth |

Error |

Rate of Error |

Loss |

|

Disease NOT caused by service |

Disease NOT caused by service |

No error |

Specificity [True Negative Rate (TNR)] |

0 |

|

Disease NOT caused by service |

Disease IS caused by service |

Failure to attribute disease to service |

1-Specificity [False Negative Rate (FNR)] |

Failure to cover veteran with SAD

|

|

Disease IS caused by service |

Disease NOT caused by service |

False attribution of disease to service |

1-Sensitivity [False positive rate (FPR)] |

|

|

Disease IS caused by service |

Disease IS caused by service |

No error |

Sensitivity [True positive rate (TPR)] |

0 |

same concept and terminology is used with regard to classification of exposures and diseases. Exposure status is often classified on the basis of incomplete or imperfect information so that some persons designated as exposed were not (false positives) and some designated as non-exposed were (false negatives). The same considerations extend to disease classification. For some diseases, there are relatively specific and firm diagnostic criteria (e.g., type 2 diabetes), while for others, the diagnostic picture is more ambiguous, (e.g., some neuropsychiatric disorders), and both false positive and false negative errors of diagnostic classification may be made.

Losses

As is nearly always the case, errors of classification have associated costs or losses. False negative errors are readily understood: a veteran who should receive compensation does not. The consequences of false negative errors elicit strongly motivated responses from all parties: veterans, VA, Congress, and society in general. Because there is strong motivation to avoid false negative decisions, a compensation scheme may be constructed to minimize the risk of making them by maximizing sensitivity (the probability of deciding in favor of compensation when a service-attributable disease has

occurred). In avoiding false negatives, however, there is usually a trade-off with the numbers of false positives, as increasing sensitivity will generally reduce specificity. In other words, planning for as few false negatives as possible increases the number of false positives. In balancing the risks of false negative decisions against numbers of false positives, VA presenters and past congressional staffers at public Committee meetings indicated a strong motivation to compensate veterans who may have been harmed by their military service, even if false positives are incurred (as stated during Pamperin, 2006; as stated during Petrou, 2006; as stated during Ryan, 2006; as stated during Scott, 2006; as stated during Yoder, 2006).

However, false positive errors may also come with losses. These include the injustice of inappropriately awarding compensation to veterans not actually harmed by their service and the unnecessary expenditure of public funds. A compensation system that tends to have a high false positive rate may become generally suspect, particularly if compensation costs escalate rapidly. Uncompensated veterans may be troubled by the seemingly high rate of compensation among fellow veterans. Balancing the losses of false negatives and false positives is difficult, as the loss from a false negative is the injustice done to deserving but uncompensated veterans and that from false positives includes economic costs along with non-economic consequences of having a non-specific system.

Service-Attributable Fraction of Disease

In public health, calculations have long been made on the amount of disease caused by a factor. One well-known example is the number of deaths each year in the United States attributable to cigarette smoking. Similarly, it is possible to estimate the amount of disease among veterans with a given exposure and given risk profile that exceeds what is observed in otherwise similar, but unexposed persons. That is, one can compare the rate of disease in exposed veterans to the rate in otherwise similar persons who were known not to be exposed. If there is a difference between these two rates, and the assumption is that the difference is due to a causal effect of the exposure on disease occurrence, then the fraction of disease attributable to the exposure can be quantified. If for a subgroup of veterans with a homogeneous risk profile, the rates of disease among exposed and unexposed are r1 and r0, respectively, then the fraction of disease attributable to service is the relative increase associated with exposure expressed as a fraction of the rate among the exposed. That is, assuming causation, the service-attributable fraction (SAF) can be calculated by the following equation:

As r1—the additional risk from exposure—increases, the term r1 becomes smaller and the SAF increases towards 1.0. Consider again the examples of battle wounds and diabetes. Because all battle wounds occur only among those in combat, r0 = 0 so that the attributable fraction is 1.0 for battle wounds. For diabetes, however, the fraction of cases attributable to service in Vietnam is likely to be much smaller than 1.0, given the existence and strength of other factors (e.g., obesity) that contribute to its causation.

Rates of disease for exposed veterans and for otherwise similar veterans who were not exposed are required to estimate the SAF of disease for a population of exposed veterans. The rates are needed for each subgroup as defined by the exposure of interest, other risk factors, and perhaps other covariates. Of course, taking account of all the various subgroups defined by the resulting array of variables is likely to be difficult or even impossible in practice. If relevant data are available, an analytic approach using a statistical model can be used for taking the covariates into account so that the SAF can be calculated for each subgroup.

To illustrate the estimation of service-attributable disease, consider the hypothetical data in Table 6-2 showing diabetes occurrence in 5,000 veterans exposed to Agent Orange and 5,000 otherwise similar, but unexposed, persons in a particular stratum of demographic and other risk factors.

In this hypothetical example, 150 of the 10,000 veterans have diabetes. Again in this example, only 100 of the diabetics were exposed to the putative cause, and thus 100/150 = 67 percent of the total funds spent on diabetes are for exposed individuals. Even among the exposed veterans, not all cases of diabetes were caused by the exposure, as 50 would be expected absent exposure, based on the experience of the unexposed veterans of whom 50 of 5,000 developed diabetes. Therefore, we can assume, absent exposure (i.e., the counterfactual), that 50 of the 100 cases among the exposed veterans would have occurred, even if those veterans had not been exposed. Hence, only the remaining 50 or 50/100 = 50 percent are attributable to the exposure associated with service in Vietnam. In this example, providing compensation for all exposed veterans with diabetes means that the false positive rate is 50 percent.

TABLE 6-2 Hypothetical Example of the Estimation of Service-Attributable Disease

|

|

Diabetes |

No Diabetes |

Total |

|

Exposed veterans |

100 |

4,900 |

5,000 |

|

Unexposed veterans |

50 |

4,950 |

5,000 |

|

Total |

150 |

9,850 |

10,000 |

In this example, the costs of compensation can be apportioned between the true positives and false positives. Assume funds of $10,000 per person compensated and three scenarios: (1) knowledge of who is exposed and has disease caused by exposure, (2) knowledge of who is exposed and no knowledge of which cases were caused by exposure, and (3) no knowledge of who is exposed or which cases were caused by exposure. In the first situation, $500,000 would be awarded, only to true positives. In the second, if the exposure status of specific individuals were known but individual causation not known, $1,000,000 would be awarded. With a SAF of 50 percent, $500,000 would be for true positives and $500,000 for false positives. If exposure status were unknown for all individuals, then the compensation scheme would award $1,500,000 including $1,000,000 for false positives. Applying the SAF of 33 percent (67 × 50 percent) to the total disability costs (150 × $10,000) again gives $500,000 in costs attributable to the exposure. In the first situation, with known exposures and disease causation, only those exposed receive payment, while, in the third, all with disease receive payment.

This simple example shows that the attributable costs for a population with a given set of characteristics are determined by two fractions:

-

Probability that a veteran was actually exposed to the putative cause given that he or she has the disease and given his or her estimated or measured exposure data and information on other relevant factors

-

Probability that the disease in an exposed veteran was caused by his or her exposure given that the veteran has the disease, and given his or her estimated or measured exposure information and information on other relevant factors

These probabilities can be estimated, if the requisite data are available; otherwise, values must be assumed. Presumptions for exposure or causation, as currently implemented by VA, correspond to assuming that these probabilities are equal to 1.0. Service in a particular theater may lead to a presumption of exposure, an assumption meaning that the probability of exposure is 1.0; with regard to causation, there may be a further assumption that the disease is caused by the exposure, again acting as though the second probability is 1.0. If either of these two probabilities were assumed to be 0, then compensation would not be awarded.

In the illustration above, we calculated a single SAF from the rates of disease among exposed and otherwise similar unexposed veterans. This calculation is based upon the assumption that we are comparing like to like persons, except for the exposure. It can be difficult to form groups of exposed and unexposed veterans that are the same with respect to

other factors affecting the disease process. Typically, statistical methods for adjustment are used to attempt to achieve this comparability.

Statistical methods, however, are only as good as the data to which they are applied. Accurate and precise estimates of SAFs depend on detailed data on exposure, key covariates, and disease outcomes. Chapter 10 provides a detailed discussion of approaches to compiling such data as an element of surveillance of veterans. To the extent that data are incomplete, a frequent situation, the estimates of the SAF will be subject to uncertainty to a degree that will depend on the extent of missing data.

Making Presumptions

To this point, we have described the concept of service-attributable disease for a population and for an individual. We have indicated that application of a presumption can be thought of as equivalent to acting as though the probability of exposure and/or the probability that an exposed veteran’s disease is caused by his or her service are equal to 1.0. We show that any scheme may lead to two types of error and that avoiding false negatives, a desirable property of a compensation system, may increase the false positive rate. One key consideration is the basis for setting the sensitivity of the approach. We have set out the losses associated with each of the two types of error. When a veteran’s illness is not attributed to a service-related exposure when it should be, he or she is denied benefits to which entitled, and an injustice is rendered. When a veteran’s illness is attributed to a service-related exposure even when he or she was not exposed (or, if exposed, the disability was not caused by that exposure), compensation is provided that is not truly warranted.

Uncertainty

Uncertainty, lack of complete and perfect knowledge, inherently affects the presumptive disability decision-making process. Presumptions are needed because information is incomplete, in relation both to causation generally and to whether specific individuals have an illness caused by service in the military. Because uncertainty is inevitably present, a vocabulary to express its extent, including adjectives such as unknown, improbable, possible, likely, or certain is needed. In using uncertain scientific evidence for decision making, we depend upon quantification of uncertainty for guidance on how to weigh more and less certain evidence.

In attributing disease to military service, uncertainty may be unavoidable for some exposures, although obviously not for others, such as a wound and its consequences. As described in Chapters 7 and 8, one necessary step in the presumptive disability decision-making process is to determine whether a disease was caused by factors related to military service.

The counterfactual notion of cause compares disease occurrence in two worlds, one with and the other without the exposure. Because only one of these worlds is observable, the likelihood of an event in the other must be predicted, and the outcome of the prediction is inherently uncertain.

The determination of whether a particular military exposure has the potential to cause a disease or condition is often subject to substantial uncertainty. Experimental studies have the advantage of having an explicit comparison group selected at random so that the counterfactual state is experimentally established. However, data from controlled experiments in human populations are generally not available and would generally not be applicable to exposures that cause disease only after a substantial period of time, as is true for many chemicals and risk for cancer. Findings from observational or epidemiologic studies of risk in exposed compared to unexposed persons, while attempting to control for other factors, are often used instead. The effort to control for other factors and to thereby assure comparability of exposed and nonexposed persons may not be fully successful, and other sources of bias may also add to uncertainty in results of observational studies. Typically, results of in vitro and animal studies of biological mechanisms are also considered. However, in using the results of such research, uncertainty arises from the extrapolation of results from cells, animals, or other systems to humans. Approaches for quantifying these diverse sources of uncertainty about causation have been developed but do not fully reflect the scope of the uncertainty and its implications for decision making. Most often, judgment of expert panels to gauge the degree of uncertainty is used as a guide to decision making.

Even if general causation is established, assignment of causation in a particular veteran may still be subject to uncertainty. Limited or no information may be available on exposure. Exposures in a war theater may vary greatly over space and time, and without detailed information on the spatiotemporal profiles of exposure and on locations of individual Service members, exposure estimates will be imprecise and possibly invalid.

Uncertainty as to individual causation would not be eliminated by having “perfect” exposure data. Conditions and diseases often have multiple causes, each possibly causing some proportion of the observed cases. Absent some marker that indicates that a particular case of disease was attributable to a specific factor, uncertainty as to causation by military service, when other factors also contribute to etiology, is inherent. Variation in susceptibility to an exposure is a further source of uncertainty in considering causation in individuals.

Uncertainty also affects the SAF, a statistic recommended by the Committee as an index of the extent of disease that is attributable to an exposure. The attributable fraction is defined as the fraction of an exposed and diseased population whose disease was caused by the exposure, meaning it

is the fraction of the population who, but for the exposure, would not have developed the disease. The value of the attributable fraction may depend on multiple factors, including the level and the timing of exposure, the dose-response curve, the time since exposure, and the baseline susceptibility of the population. The true function relating the attributable fraction to exposure is unknown in terms of both its general form and its specific values. We estimate the function describing the attributable fraction from finite data that are subject to variability. Hence, there is typically uncertainty in estimates of the attributable fraction used to describe the burden of disease attributable to an exposure and to assess whether disease in an individual veteran was caused by service.

Scientists have constructed mathematical systems to quantify uncertainty; the theory of probability is the most widely applied. There are two distinct notions of probability: frequentist and subjectivist. In the former, probability represents the long-run frequency of events. For example, the probability of a heads or tails represents the fraction of heads or tails out of a large number of coin tosses. Subjectivist probability is instead an expression of belief about the likelihood of an event. For example, we represent an individual’s risk of disease as a probability between 0, indicating no chance, and 1, indicating certainty. For either notion, there is the same precise calculus for representing, combining, and manipulating probabilities as measures of uncertainty.

In subsequent chapters, the Committee sets out concepts related to general and specific causation that are critical for improving the current approach to making presumptions.

SUMMARY

This chapter introduces some of the key concepts involved in using scientific evidence as the basis for compensation of groups of exposed individuals. It sets out the need to determine general causation and to consider how much disease is attributable to exposure. These concepts are elaborated in subsequent chapters. Gaps in the scientific evidence on exposure and causation lead to a need for presumptions. Chapters 10 and 11 address how surveillance of exposures and disease among active duty personnel and veterans could reduce these gaps.

REFERENCES

Pamperin, T. J. 2006. An overview of the disability benefits program and presumptions affecting veterans’ benefits. Paper presented at the first meeting of the IOM’s Committee on the Evaluation of the Presumptive Disability Decision-Making Process for Veterans, Washington, DC.

Petrou, L. 2006. Statement presented at the third meeting of the IOM’s Committee on the Evaluation of the Presumptive Disability Decision-Making Process for Veterans. San Antonio, TX.

Ryan, P. 2006. Perspectives on veterans’ legislative disability presumptions. Paper presented at the third meeting of the IOM’s Committee on the Evaluation of the Presumptive Disability Decision-Making Process for Veterans, San Antonio, TX.

Scott, E. P. 2006. Statement presented at the third meeting of the IOM’s Committee on the Evaluation of the Presumptive Disability Decision-Making Process for Veterans. San Antonio, TX.

VA (Department of Veterans Affairs). 2002. Veterans health initiative. Independent study course. Vietnam veterans and Agent Orange exposure. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs. http://www1.va.gov/agentorange/docs/VHIagentorange.pdf (accessed May 12, 2007).

Yoder, C. 2006. Thoughts on presumptions of service-connection for veterans presumed to have been exposed to environmental hazards. Paper presented at the third meeting of the IOM’s Committee on the Evaluation of the Presumptive Disability Decision-Making Process for Veterans, San Antonio, TX.