3

Models for NASA Astronomy Science Centers

There is a virtual continuum of models for NASA astronomy science centers, and NASA has tried several. The models can generally be characterized as “mission” centers, “science” centers, and “archival” centers, although the boundaries are not sharp. What is certainly true, however, is that centers are usually born with responsibilities for specific space-based astronomy missions.

This chapter discusses five models for science centers—traditional mission centers, Explorer-class mission centers, guest observer facilities, archival centers, and flagship mission centers—and the services they provide. Factors affecting the size and scale of the centers, as well as breakpoints in the level of service, are also discussed.

FIVE MODELS AND THE SERVICES THEY OFFER

Traditional Mission Centers

Traditional space-based astronomy mission centers are dedicated to a single mission. The simplest are exemplified by the centers for small principal investigator (PI)-class missions prior to about 1980. Such PI mission center functions included little more than PI activities that supported mission operations and data analysis, without any significant guest observer or archival research program. Although a NASA mission that does not provide some guest observer utilization is essentially a relic, there are still a few missions, such as the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe, for which it makes no sense to have a guest observer program during the mission’s operational phases.

The next step up in complexity for a mission center is for an Explorer-class mission with a guest investigator base that is likely to be limited to discipline experts. Recent examples include the Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer (FUSE), which is still operating, and the Extreme Ultraviolet Explorer (EUVE), which completed its operations in 2001. In both cases, the PI group can be contracted by a NASA center to operate the spacecraft; the PI group plans and carries out both the science and mission operations with minimal NASA oversight. NASA usually requires a formal guest investigator program and insists that the data be archivable in usable form, but the support for both these activities, FUSE

and EUVE, is relatively small. Swift is a current real-time mission that conforms to this general model. Swift science and mission operations are handled by the PI at the Goddard Space Flight Center, with substantial efforts in both mission and science operations contracted to coinvestigators at Pennsylvania State University. The Swift data are promptly available via the High Energy Astrophysics Science Archive Research Center (HEASARC), within seconds for the gamma-ray burst detections, and are quickly accessible and archivable for longer-term analyses.

Explorer-Class Mission Centers

Somewhat more complicated in their mission operations are those Explorer-class space astronomy missions that are expected to have significant guest investigator involvement. Operated out of the Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC), the Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer (RXTE) mission is an all-guest-investigator mission, without guaranteed observatory time for the scientific staff but with some guaranteed research time that a staff member can use to propose for observatory time. The RXTE science operations center is responsible for the detailed scientific planning of the mission operations, the coordination of the colocated contractor flight operations team, and postacquisition data processing. RXTE staff provide preproposal simulation software and proposal support, as well as data analysis software, to its guest investigator community.

The RXTE center also reviews proposals for guest investigations on behalf of NASA Headquarters. While NASA Headquarters has responsibility for approving the grants and contracts that are associated with guest investigations, the review of proposals (i.e., evaluating proposals for technical merit, convening teams of proposal reviewers from the scientific community for evaluating scientific merit, and making recommendations for proposal acceptance) has now been tasked to mission centers in the overall statement of work.

RXTE, much like other Explorer-class missions, is required to have an EPO plan and has a small budget and fractional staff time devoted to it.

Guest Observer Facilities

A variation on the small mission center described above is a guest observer facility (GOF). GOFs do not have mission operations responsibilities and provide only support to guest observers. A good example is the XMM–Newton GOF at the GSFC, which provides functions specifically associated with NASA support to U.S. guest observers since XMM–Newton is a mission of the European Space Agency, whose science and mission operations are conducted in Europe. Virtually all center-provided functions are now accessed remotely, so that the NASA-specific functions are related to value-added support for proposal preparation and data analysis for U.S. guest observers. GOF provides a user guide for XMM–Newton data analysis, manages the budget proposal process for U.S. guest observers, and provides preproposal support as well as a help desk, although the GOF budget limits the extent of the support that can be provided. But, since the scientists associated with the GOF and the HEASARC are XMM–Newton users, the help-desk support is expert and the standard HEASARC analysis tools1 for XMM–Newton data are well supported and effectively utilized by the U.S. guest observer community for XMM–Newton. Similar to the XMM–Newton/HEASARC relationship, the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center (IPAC) supports U.S. users of the European Space Agency’s Infrared Space Observatory.

Archival Centers

At the mid-range of complexity are archival centers, which provide an umbrella structure for continuing archival and support services after space-based astronomy missions reach the end of their operational lifetimes. The Multimission Archive at the Space Telescope Science Institute (MAST) is located at a mission-oriented center and therefore differs somewhat from HEASARC and IPAC. HEASARC, for example, provides access to ROSAT data and provides user support tools for retrieving and analyzing the data. Archival centers also provide archival services for operational missions such as Swift at HEASARC and the Wide Field Infrared Explorer at IPAC, which is the umbrella for the Spitzer Science Center (SSC) and the Michelson Science Center (MSC).

A practical advantage of associating archival functions with a science center is that the arrangement provides continuing support for at least a skeleton staff of expert users independent of mission requirements. HEASARC is a good example of how the same personnel, data management tools, and basic data analysis software have been used with multiple space-based astronomy mission GOFs operated in the HEASARC environment. The multiplexing of data users and scientific software developers is a win-win-win situation for the stability of center staff, for the efficient utilization of NASA resources, and for the benefit of the user community.

Much like other science centers, the archival centers provide EPO services, help-desk access, and other science support services to the community in addition to the EPO activities of the individual missions associated with the archive center.

Flagship Science Centers

At the high end of complexity for NASA astronomy science centers are those associated with flagship missions like the Hubble Space Telescope, the Chandra X-ray Observatory, and the Spitzer Space Telescope. These centers perform the same basic support functions for guest investigators as do the centers for Explorer missions, including help-desk services, proposal software and proposal preparation support, data archiving, and analysis software, but the scale of each support function is generally much larger. NASA clearly expects that the flagship centers will take extensive responsibility for NASA EPO activities (and will therefore have specialized staff). For example, the flagship centers provide extensive printed and multimedia products for schools and museums, press releases and information for the media, Web-based materials for Internet users, and formal educational products for K-14 curricula. In addition, the flagship centers have generally been given significant responsibilities in all three of the center functionalities just noted: mission operations, science support, and archiving.

There are, however, restrictions on the breadth of activities that NASA will allow the flagship centers to pursue. For example, the charter of STScI specifically precludes it from taking a leadership role in the engineering aspects of new instrument development.

FACTORS AFFECTING SERVICE AND SIZE OF CENTERS

The committee looked across the different kinds of astronomy science centers (in particular at the GOFs and flagship centers) in terms of their budgets, size and role of their staff, centralized or decentralized architectures, and governance structures and oversight, considering the disadvantages and advantages of the various models and approaches. These factors are compared in Appendix A and Table A.1 and are discussed below.

Budgets

It was apparent to the committee that differences between the cost of similar services at various centers could be attributed to specific contractual arrangements with NASA. (An investigation of such contractual details is beyond the scope of this study.) It was also apparent that science centers affiliated with nongovernmental entities and under contract to NASA benefit from a degree of resource stability, at least for the duration of the contract period. Their independence from the government also allows them to advocate for the science community and for their center and to seek sources of funding other than NASA.

Size, Role, and Status of Staff

Some centers have mission operations responsibilities, which automatically affects the size of their staff. All science centers, however, provide a high level of science support to the user community and employ research scientists who are themselves users of the mission data to facilitate the use of data from their particular mission.

The degree to which centers use scientists and the amount of time those scientists have available for independent research distinguishes one model from another. For Explorer-class missions, staff scientists may devote more than a decade of their careers to the mission. Even so, an Explorer mission may not support all of their time, even during its active phase, and not even a fraction of their time for the rest of their career. For longer-lasting centers, however, it is assumed that a center will not be able to attract excellent staff unless it provides guaranteed research support for virtually an entire career, and this assumption changes the scale of science support substantially.2 It can even be argued that the presence of excellent scientists who are free from support activities and free to pursue their own research serves to attract excellent support scientists. The presence of these scientists, provided through a visiting scientist program, elevates the intellectual atmosphere in which the support scientists perform their functions for the community.

The number of EPO staff also has an impact on the services a center is able to offer. The flagship mission centers have over 20 times as many staff for EPO as Explorer-class or GOF centers (see Appendix A), with NASA having intentionally requested and funded large EPO efforts at the flagship centers. Centers with larger EPO staff can offer a wider range of services and educational tools than the smaller centers. However, individual PI or Explorer-class missions leverage EPO products from their umbrella institutions, such as HEASARC, and are able to reach larger audiences and provide more EPO services than they would on their own.

Centralized Versus Distributed Architectures

Flagship centers such as STScI and the Chandra X-ray Center (CXC) conduct both mission operations and science operations at a central location; other centers follow a distributed approach. The SSC, for instance, handles science operations (e.g., scheduling of observatory sequences), and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and Lockheed Martin Astronautics manage spacecraft engineering operations. Explorer-class missions such as RXTE locate the science operations center and the guest observer facility in a building next to the mission operations center. Explorers such as Swift also use a distributed approach, with a university managing instrument operations, a NASA center operating the satellite, and the NASA archival center, HEASARC, providing archival services.

Several center staff members reported on the need for strong linkages among operations engineers, instrument teams, software developers, and support scientists. Locating mission operations and science support activities nearby may strengthen those linkages.

Governing Institution and Governance

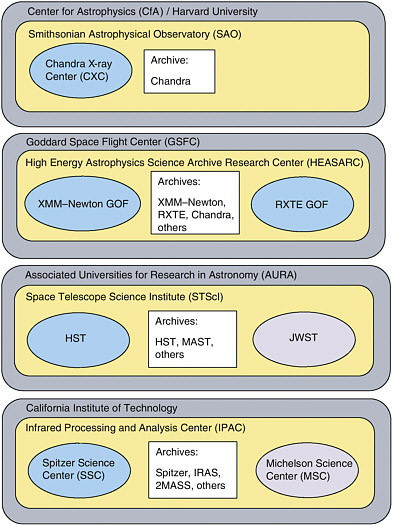

Science centers take a range of approaches to governance. Exercising a high level of independence, the STScI is governed by a separate association that holds the contract for the STScI, has responsibility for hiring the director and deputy director, and oversees the work of the STScI. SSC and MSC are governed by JPL program management; directorships of the centers are held by academics in the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) Division of Physics, Mathematics, and Astronomy. Caltech manages JPL, so all Caltech policies apply to SSC and MSC. The CXC is operated by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory as part of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. The NASA GOFs and HEASARC are government entities under the direction of NASA’s GSFC. Figure 3.1 depicts the science centers examined for this study, their host institutions, and the key archives held.

Oversight of Centers

Science centers undergo several types of formal reviews. NASA provides formal management targets that the science centers are obliged to meet and also convenes senior reviews,3 a means by which the community can help set priorities for the guest observer support associated with each mission. Centers under contract to NASA comply with formal processes such as quarterly reviews and Independent Implementation Reviews. In addition to the NASA reviews, the centers have devised their own performance measures, which often include tracking the number of proposals submitted and accepted for observations on the telescope or observatory, the data ingested and data accessed from the archive, the number of refereed papers published using data from the archive, and observing efficiency.

All centers reported on the user committees (committees of outside users) that provide feedback and direction to the center on its support services. Staff from the centers that were studied commented on the senior review process, finding it to be a form of performance review that ranks the center’s scientific contribution relative to that of other centers. Some centers also bring in outside experts to review their EPO activities; others cover EPO performance in the senior review.

SUMMARY

It was clear to the committee that all of the center models could provide valuable services to the community but that the smaller GOF and Explorer-science centers lack the resources and staff to offer a full range of science center services (see Chapter 2). Associating GOFs or Explorer centers with the larger archival centers or flagship mission centers, which have staff and infrastructure in place, enables the smaller centers to leverage skills and services and better serve their scientific constituents.

One benefit of the archival centers is their ability to accommodate mission centers at varying stages of operation and to move science staff among projects as missions start up or wind down, providing stability and flexibility. These archival centers also provide proposal and analysis software, search tools,

FIGURE 3.1 A guide to the institutional arrangements for the NASA astronomy science centers considered in this study (STScI, SSC, CXC, XMM–Newton guest observer facility, RXTE guest observer facility, and MSC). The largest boxes show the host institutions for the centers, the next-largest boxes (yellow) show the umbrella organizations, and the ovals show the NASA astronomy science centers. The blue ovals are operational centers and the screened ovals indicate missions/centers under development. The white squares show the missions whose data are archived at the umbrella organization. Only the NASA astronomy science centers and their archives considered for this study are included. Umbrella organizations such as HEASARC and IPAC encompass other NASA centers for both mission operations and archives, as described in the text. For definitions for acronyms, see Appendix D.

and other resources that users can apply to multiple databases held by the archive. Further benefits accrue in the knowledge base that staff acquire from one mission to the next, which allows for transferring best practices and lessons learned among missions.

The committee viewed the presence of research scientists and visiting scientists as a positive enhancement of a science center’s role and its ability to provide an exciting and intellectually rich environment. It was recognized that staff scientists can best serve the community if they are themselves involved in active research, so that some fraction of their salaried time should be allocated for their own research. The committee believes, however, that it is not necessary to have full-time researchers for a science center to serve the community effectively and that all the scientists at a center should be involved, at some level, in facilitating the mission.

The committee saw no evidence that the centers as a whole prefer one approach or the other—centralized or distributed. Several center staff members emphasized the need for strong linkages among operations engineers, instrument teams, software developers, and support scientists.

The committee does not view the differences in governance at the centers as having any effect on the services provided or on the ability of users to influence a center’s functions. The committee believes that oversight of the centers is sufficient. A center’s independence from NASA and an intermediate degree of governance structure, however, did appear to have advantages for the long-term security of a center. For example, STScI and CXC are under contract to NASA and are not dependent on annual appropriations in the NASA budget cycle, as are the GOFs and HEASARC. Centers that are not governmental can advocate for themselves and seek sources of funding other than NASA to support their activities. At the same time, the centers that have intermediate governance structures may take longer to respond to community input as a result of the additional layer of management in their systems.

FINDINGS

After visiting the centers and analyzing their activities—mission responsibilities, operations, personnel levels, help desk, archiving, and EPO activities—the committee discerned break points in service that, not surprisingly, correlate with levels of funding. These are readily deduced from an analysis of Tables A.1 and A.2 in Appendix A.

Seen from a broad perspective, Explorer-class missions and GOFs funded at less than $10 million per year struggle to supply basic services to the community. On the positive side, because these centers are embedded within larger NASA field centers, their staff can call on the time and expertise of a wide variety of people, an efficient way to accomplish an array of tasks. This access and the often-heroic efforts of very dedicated and highly motivated staff make these centers somewhat effective in serving the research community, but only minimally so, as the committee heard in testimony and learned from site visits. These centers simply do not have the funding to support a wide enough range of activities to move the scientific research crisply ahead and derive the full benefits of the observing facilities. Funding at $10 million or below does not allow for much, if any, instrument support and calibration, data analysis and Level 1 processing, software development, help-desk activities, user workshops, or symposia. EPO at these centers struggles to find a voice. Perhaps most important, research by center personnel, postdoctoral fellows, and visiting scientists, essential for deriving the maximum benefit from a facility because of its catalytic effect on flight operations, software development, help desk, and other services, cannot be funded. Despite the remarkable, even heroic, efforts of the staff at these facilities, the committee feels that the funding is insufficient to support the community as astronomy moves toward more and more multiwavelength research.

STScI, Chandra, and SSC/IPAC on the other hand, funded at several tens of millions of dollars per year, set the standards for the provision of services to the community.4 Clearly the research community has come to rely on the service these facilities provide. Also, as mentioned elsewhere in this report, the full complement of services and the integration of the continuum of expertise from flight operators, engineers, programmers, researchers, EPO specialists, and a variety of support personnel multiply the value of the space observatory and the scientific results that can be achieved beyond what could be achieved with a linear extrapolation of the funding.

Owing to the lack of models of intermediate size ($20 million to $30 million), the committee could not assess the potential efficacy of centers in this case. Where such centers would fall on the curve of funding versus service remains to be explored. However, one can posit that there must be a threshold level of service (and hence funding) below which the synergistic effects of the full complement of talent, activities, and services—and hence the overall value to the science and the nation—drop, most likely, rapidly.

After considering various models for NASA astronomy science centers and the factors affecting their size and utility to the community, the committee finds that CXC, STScI, and the science center complexes in Pasadena, California (JPL-Caltech) and Greenbelt, Maryland (GSFC) contain a number of activities that could (in principle, and often in practice) grow with respect to both personnel and physical plant resources. These science centers should become the natural hosts for continuing support of ongoing research that utilizes NASA’s data resources after individual mission centers have outlived their charters. They make up an effective infrastructure that could serve both existing and planned missions well. The committee recognizes, however, that missions such as the Terrestrial Planet Finder, Laser Interferometer Space Antenna, Space Interferometry Mission, and Constellation-X, if they are developed, might need more capabilities, expertise, and user support services than are provided by these four science center complexes and might even justify additional NASA astronomy science centers in the future.

Finding: Embedding guest observer facilities in existing science centers such as the High Energy Astrophysics Science Archive Research Center provides for efficient user support, especially when the scope of a space mission does not warrant a separate science center.

Finding: The Chandra X-ray Center, the Space Telescope Science Institute, the High Energy Astrophysics Science Archive Research Center, and the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center have sufficient scientific and programmatic expertise to manage NASA’s current science center responsibilities after the active phases of space astronomy missions are completed.

Finding: The ability of the Chandra X-ray Center, the Space Telescope Science Institute, the High Energy Astrophysics Science Archive Research Center, and the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center to provide the appropriate level of support to the scientific community depends critically on the extent to which they can attract, retain, and effectively deploy individuals with the mix of research and engineering skills necessary to maintain continuity of service.