2

Lessons from Electronic Services in Financial Institutions

Although much about the Social Security Administration (SSA) is distinctive, in some ways the SSA, its activities, its information technology (IT) needs, and its operational characteristics are analogous to other organizations outside the federal government. This chapter explores that premise and seeks to identify ways in which these organizations and institutions outside the federal government are dealing with some of the challenges that currently face the SSA in the realm of electronic services.

The committee recognizes that the SSA might not be able to—or want to—use “as is” all of the approaches and solutions pursued by other institutions. Some activities that citizens conduct with the SSA involve one-time, very personal, potentially traumatic events in their lives—at such times people desire the personal contact and support that traditional service-delivery options offer. Another stark distinguisher is the SSA’s funding model. The agency has a budget limited by the congressional appropriations process. It is required to balance its spending of the appropriated funds. Given the federal context in which it operates, it cannot, as a general rule, raise new funds by attracting more business, nor can it easily justify exploring, then abandoning new services on the basis of a trial offering of new services as the financial industry might do. In practice, new services must readily be demonstrable to be in the public interest, and the benefits of providing those services should outweigh the benefits of developing other services competing for the same limited pot of funds.

There is nonetheless substantial value in considering what might be learned and what might be adapted or applied as a result of studying organizations that only provide somewhat-analogous services—if more-routine and less-personal interactions can be accomplished efficiently and with less staff overhead through the use of electronic services, that could, as an additional benefit, help to make more resources available for when more-personal service is needed. This chapter examines large-scale financial institutions having high-volume interactions with large numbers of individuals. The financial services community has been one of the most aggressive and competitive in using IT and electronic commerce. While the SSA is, appropriately, neither as aggressive nor competitive, there are ways in which financial institutions are dealing with situations that are relevant for the SSA. In addition, unlike more recent Internet-based companies such as Amazon or eBay, major financial institutions have had to undergo a transformation away from primarily bricks-and-mortar-based organizations to take advantage of and move into electronic service provision, a transformation much like what the SSA faces. At the same time, there are few “online-only” banks, meaning that most financial institutions have had to expand the kinds of channels through which they offer services, not replace them. Learning from their experience of that transformation may also be instructive for the SSA.

THE TRANSFORMATION IN FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS

Just two decades ago, banks’ interactions with their retail (individual) customers were almost exclusively walk-in or telephone transactions. Deposits and withdrawals were generally carried out in person, and account statements were printed on paper and sent through the mail, usually monthly. All of that started to change with the widespread deployment of automated teller machines (ATMs) and the creation of centralized call centers. In the 1980s, many services were introduced through proprietary services delivered to personal computers, screen phones, and television sets. However, the story of mass adoption, as well as economically feasible delivery of these services, begins in the mid- to late-1990s with Web-based delivery, fueled by growing public use of the Internet. The net effect of these changes has been to alter the entire character of the retail banking industry dramatically and to transform the way in which it is both used and perceived by its customers. Although not every bank has been as aggressive in all dimensions, there are lessons to be learned from best practices in the aggregate in the industry.

Some aspects of the role, activities, and operations of the SSA have much in common with those of a large commercial bank or brokerage house that maintains accounts and receives and makes payments. These

institutions usually conduct transactions in multiple customer segments (individual retail customers, businesses, other financial institutions, and so on) and through multiple service channels (online, through ATMs and branch offices, through call centers, and so on). For reasons of cost and competitiveness, most such institutions have seen increasing value in emphasizing online customer channels to their services. From a coarse technical feasibility perspective, the databases that are maintained by private-sector institutions are now quite comparable, both in size and in transaction volume, to the databases for which the SSA is responsible (see Chapter 3). At least one major credit card issuer has 170 million open accounts, comparable with the SSA’s approximately 140 million Social Security statements issued annually. These observations suggest that the experience, market research, and product-refinement knowledge accrued by these financial institutions during the past 15 years, as well as the set of practices and approaches to effective information- and service-delivery capabilities and customer service that they have developed, can be strongly relevant to the SSA. An examination of the commercial financial services industry offers relevant insights and lessons learned for effective electronic services. These can be useful to the SSA and other government agencies seeking to make more comprehensive and effective transitions to online services.

Online banking, in particular, seems to be a relevant, if not completely analogous, success story. A segment of the public has embraced the convenience that comes from immediate access to virtually up-to-the-minute information about personal finances 24 hours a day, 7 days a week (24/7).1 Bills can be paid online and money can be transferred at all hours. Banking customers now expect that they can track the flow of money both into and out of their accounts at all times. Thus, 24/7 access has become the expected norm. Given that the SSA offers some similar types of services—albeit usually at a different frequency (monthly account changes instead of daily or hourly changes, for example)—this expectation is a reality that the SSA must confront. The SSA’s current clientele is generally older, less abled physically and/or cognitively, and less financially well off than the general population of online bill payers. However, as the current population of online bill payers ages and starts using SSA services, their expectations will likely transfer to the SSA. Unlike today’s population of people

|

1 |

According to the Pew Internet and American Life survey of online banking in 2005, “fifty-three million people, or 44% of Internet users and one-quarter of all adults, now say they use online banking. Those figures amount to an increase of 47% over the number of Americans who were performing online banking in late 2002.” In 2006, that number had increased: “Fully 43% of Internet users, or about 63 million American adults, bank online.” See http://www.pewinternet.org/PPF/r/149/report_display.asp, accessed July 10, 2007, for more information. |

65 and older, in another 10 years the people who are 55 to 65 and older will be much more technology-savvy. Thus, a forward-looking electronic service strategy should contend not only with the constituent population of today, but also with the likely constituent population of the future, which will inevitably be more technologically sophisticated. In addition, transaction and information services online have a significant cost benefit versus in-person or call-center alternatives.

The public is becoming accustomed to gaining access to personal banking information through bank or brokerage Web sites that present a smooth, seamless interface to a wide range of related services. Thus, banks, for example, now present to the public comprehensive Web sites through which customers can access information about their checking accounts and mortgage balances, while also viewing real-time stock market information, and can also access increasingly comprehensive ranges of other financial information and services. Some of the information accessible through such portals (for example, stock market data) is not owned by the portal maintainers themselves but is furnished as a convenient service. There seems to be a growing expectation that institutions such as financial services organizations will provide comprehensive access to data that their customers feel they need. This, too, is a characteristic of the world that the SSA will increasingly have to come to terms with. Such expectations are likely to hold, even though most people will deal with the SSA only infrequently.2

The SSA’s many users are active participants in this world that is continuing to embrace such comprehensive 24/7-Internet-accessible services. Internet-connected computers are increasingly present in homes, and a growing majority of the public increasingly looks to these computers as vehicles for information and timely, convenient, online transactions. Although younger individuals may have been the first to grasp this new medium as a routine source of both information and service, older seg-

ments of the public are making similar changes to their expectations and habits (see Chapter 4). Search services such as those provided by Google and Yahoo! are increasingly used to locate information and service providers. Both public and private service providers are increasingly encouraging online access to their services: the public is becoming accustomed to shopping online, tracking the progress of parcel deliveries online, paying bills online, and renewing driver’s licenses online.

One important reason for this shift in delivery channels is that service providers generally find that online transactions are less costly than in-person or telephone transactions.3 This situation has changed significantly in the past 10 years, especially in the United States and to the advantage of online transactions.4 Also, the 24/7 availability of such services makes them particularly convenient for customers and other users; convenience builds customer satisfaction and loyalty, both to the institution and to the online service channel, making it even more attractive for the service providers. Modern retail and institutional businesses generally view customer satisfaction as a primary metric, along with cost.

With respect to the SSA’s mission requirements, the delivery of financial services has some compelling analogies to the delivery of benefits to citizens. For example:

-

Customers expect their financial institutions to keep track of their accounts flawlessly and to handle transactions with complete privacy, security, and efficiency;

-

Large financial institutions have transaction volumes comparable with those of the SSA (partially due to consolidation5 in the bank industry); and

-

A large proportion of customer transactions have moved online in the past 10 years.

|

3 |

For instance, an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) study reported that by the late 1990s, traditional branch banking customer service cost $1.08 per transaction, compared with $0.13 per transaction for Internet-based e-business. (That is, e-business provided an 88 percent cost savings per transaction.) That same study reported that telephone-based banking customer service cost $0.54 per transaction, indicating significant cost advantages to shifting service from phone to online. OECD, The Economic and Social Impact of Electronic Commerce: Preliminary Findings and Research Agenda, Paris, France: OECD, 1999, http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/3/12/1944883.pdf, accessed June 20, 2007. |

|

4 |

With the convergence of voice and data and the emergence of Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) and speech recognition, the cost differences between call centers (for automated transactions) and the Internet are narrowing. |

|

5 |

The efficiencies provided by integrated electronic services have been substantial drivers for the consolidation that has taken place. |

The following sections describe the state of the practice in the financial services industry and note parallels and potential lessons for the SSA and other agencies. While the committee is focused on the SSA, the lessons here are broadly applicable and should not be construed to imply that the SSA is alone in facing these challenges.6

TYPICAL ONLINE CAPABILITIES

Online services made available by banks encompass essentially anything except cash withdrawal and check or cash deposit. Routine banking transactions now increasingly occur online, leaving customer service representatives at call centers and branches to handle the more complex situations (and sales opportunities). For brokerages, online transactions can comprise over 90 percent of their total interactions with their customers. There are several categories of online capabilities, and while each plays a role in the delivery of services, they are at different points of maturity and adoption. Several of these capabilities are described below.

Product Information and Service Aggregation

Ideally, all products and services delivered by a financial institution are described in detail on the institution’s Web site. This amount of information can be overwhelming, so in virtually all cases there are three ways in which information tends to be found and accessed: by looking for links corresponding to a need or precipitating event (for example, marriage); by looking for a particular product type (for example, loan account); and through a simple text search (for example, “cd rates”). All three mechanisms are widely used by customers, although search has increased in importance as Internet users have become habituated to the search box as the point of entry to content.

Over time, customers have grown to expect that their relationship with a single institution can be managed almost entirely online in a seamless fashion. Therefore, although retail banking, credit card, mortgage lending, and brokerage units (for example) are usually separate business units within a financial institution, customers expect them to be available in one place, with one log-in. Although most in the industry no longer think of this as “aggregation,” it has required financial institutions to gather information from different systems, with different rules, and often from legally separate businesses, and to make them appear to be a single cohesive system that provides “one-stop service.”

Another form of aggregation is the gathering and organizing in one place of account information from multiple financial institutions. This aggregation can also be applied to nonfinancial accounts such as frequent-flyer miles, e-mail accounts, and so on. Intuit’s Quicken as well as several financial institutions’ Web-based aggregation services (such as Bank of America’s My Portfolio and Fidelity’s Full View) are examples. Another type of aggregation service that is being adopted is Bill Presentment, which assembles and organizes incoming bills to make them ready for payment. Coupled with online bill payment, this service eliminates the round-trip first-class mail circuit of receiving a paper bill and paying it by paper check.

Relevance for the SSA and Other Agencies

In order to design and deliver content through a Web site with state-of-the-practice functionality, an organization should conduct a thorough review of content and access to that content. What are the obvious high-level “types” of material or services that users might be looking for? The committee has not conducted a detailed analysis of this issue, but examples for the SSA might be “retirement benefits,” “disability application,” or “earnings data.” Web pages, especially home pages, that are “flat” in structure, with a large number of disaggregated links, can appear cluttered, disorganized, and confusing to users. (See also the discussion in the section entitled “Financial Institution Web Site Design” below.) The public expectation that an individual will be able to find and access all of his or her benefit accounts in one place will continue to grow. Accordingly, a seamless presentation of any benefits or services to users that is facilitated by effective search capabilities—even if the management of those benefits crosses organizational lines—is preferred.

Account Management and Money Movement

Account-management and information activities include such tasks as looking up balances and terms. These activities once comprised the bulk of volume of online “transactions” for banks. Simply answering the question “How much money do I have?” was much simpler to do online for a segment of customers than to use the telephone (where inquiries of this kind are usually handled by an automated interactive voice response [IVR] system and can be quite cumbersome), an ATM, or a branch teller. Most account-management features also allow users to query balances or move funds among accounts or products after signing on to the Web site once. As an example, most users of online banking can log in to their financial institution’s Web site and see information on their savings and checking accounts, their mortgage, credit cards, and possibly their retire-

ment funds if they have chosen to consolidate their financial dealings with one firm.

Money-movement activities in financial institutions include account-to-account transfers (within the institution), bill payment, and account-to-account movement to other institutions. Of these, bill payment services have caused the most dramatic changes in customer behavior. U.S. banks have historically played only a limited role in consumer bill payment. While some activities, such as recurring automated payments for fixed amounts (such as mortgage payments) and telephone-based “pay anyone” services were available in the 1990s, there was very little adoption of these services. Online bill payment is now used by approximately half of online customers. Bill payment has fundamentally changed those consumers’ interactions with their banks, both in terms of frequency of interaction and “stickiness”7—a “sticky” Web site has features that cause visitors to spend more time on the site and to return to the site. Thus, stickiness helps retain customers in the electronic service-delivery channel.

Brokerages and brokerage arms of banks offer every type of trading capability from buying and selling of simple securities and mutual funds to limit orders and option puts and calls. Trading online is today the standard way for individual investors to interact with the markets.

The ability for consumers to manage their accounts interactively online presents myriad security and access-control challenges. While this report’s focus is not on security per se, it is a critical component of any electronic services strategy, as the SSA is appropriately aware. As financial institutions deploy and advance their own security strategies, there will likely be lessons for the SSA and other government agencies in how those institutions proceed.

Authentication for consumers on Web sites of financial institutions generally consists of a log-in and a password. Some of the banks with the highest rates of adoption for online services have used an authentication scheme that is already known to the customer—his or her ATM card number and personal identification number (PIN)—and required no extra enrollment step. The October 2005 guidance on authentication from the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council has been changing this situation fundamentally; it requires multifactor authentication for banking transactions by the end of 2006.8 Most banks have implemented some risk-based approaches to authentication (additional verification of

|

7 |

See http://www.arraydev.com/commerce/JIBC/9908-03.htm, accessed June 20, 2007; and M. Khalifa, M. Limayem, and V. Liu, “Online Consumer Stickiness: A Longitudinal Study,” Journal of Global Information Management 10(3):1-14, 2002. |

|

8 |

Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, “Authentication in an Internet Banking Environment,” FIL-103-2005, Oct. 12, 2005. See http://www.fdic.gov/news/news/financial/2005/fil10305.html, accessed June 20, 2007. |

high-risk transactions such as funds transfer—for example, out-of-channel verification and/or stronger authentication) and employ layered authentication (for example, a minimum of identification [ID] and password, other knowledge-based checks, plus behavioral anomaly detection; two-factor authentication is also being introduced for the riskier interactions).

Another large issue here is better authentication of the financial institution’s Web site and e-mails to the customer—which is currently a major vulnerability, given the prevalence of “phishing” scams.9 The Financial Services Technology Consortium has launched the project “Authenticating the FI [Financial Institution] to the Consumer” to address this issue.10

Relevance for the SSA

Despite the SSA’s early unsuccessful experience with making the Personal Earnings and Benefit Estimate Statement (PEBES, discussed briefly in Chapter 4) available online, if the SSA wishes to deliver state-of-the-practice electronic services, then online access to individuals’ Social Security Statements of Earnings and other account information will be a required and basic function. Given the near ubiquity of such functionality in the financial services sector, as time goes on its lack will appear increasingly strange to a user base that is ever more technologically experienced. The implication is that users are accustomed to a high-value proposition in their online transactions that makes it more attractive to use electronic transactions than transactions by telephone or in person. If the SSA does not provide such a compelling set of services online to its users, they will remain loyal to the traditional service-delivery channels that they have become comfortable with in the past.

The SSA will never (and should not) remove the customer’s ability to contact a human if desired; however, in order to attract and retain users in online channels, the SSA should strive to provide a consolidated view to users across program lines, even if the programs are run by different parts of the SSA organization—for example, a consolidated view of retirement benefits and disability benefits. Such provision may benefit from technology and data infrastructure that would support the capability for users

|

9 |

“Phishing” is an attack that tricks a user into entering sensitive information (such as account numbers, log-in names, and passwords) at the wrong Web site, making it available to attackers. The most common example is an e-mail from a bank stating that there is an irregularity in payments or accounts that the recipient must attend to, and a link for the recipient to follow. But the underlying link takes the recipient to the attacker’s Web site, which looks like the bank’s legitimate site. The recipient follows the link and enters the information to access the account. The attacker can now also do so. |

|

10 |

See http://www.fstc.org/projects/current/authfi_home.2007.php, accessed June 20, 2007, for more information. |

to authenticate themselves once to gain access to a variety of information and services across the SSA. (As more users access services over the Internet, “phishing” may also become a larger security risk for the SSA.)

Customer Service

In financial institutions, straightforward customer service activities such as opening or applying for accounts, ordering checks, changing one’s address, and changing beneficiaries have moved online steadily. When third parties are involved, such as in ordering checks, and even in many cases when they are not, financial institutions had been slow to offer the option of “pre-filling” known customer information, making the online process more tedious. The more advanced sites now deliver that capability to authenticated customers and, as a result, provide more personalized services, thus making those services more convenient for users. With respect to opening accounts, banks and brokerages have been moving steadily away from simply making application forms available online toward offering fully interactive, “pre-filled” and streamlined application processes.

Relevance for the SSA and Other Agencies

Maintaining multiple channels for people to access services is important (apart from a very few online-only banks, financial services institutions maintain several use channels). Indeed, there may be lessons to be learned from the financial services sector with respect to state-of-the-art telephone triage and automation as well. Nevertheless, the state of the practice in retail financial institutions is to make available online all common services that are feasible from the customer’s perspective. When the SSA is unable to provide a service electronically—for example, owing to regulation—clear explanations and alternative means of access are an important part of a comprehensive service-delivery strategy.

Where appropriate, a form or forms should be made available (not just as a printable blank form, but as a printable form that can be both filled in and submitted online) with detailed instructions on other needed materials and on how the applicant can complete the process. The state of the practice for online services today is that common information should only be provided once. For the SSA, this suggests that when a life event requires multiple forms for multiple programs, the common information should only be requested once. Pre-filling for authenticated users (such as current beneficiaries) should be the norm,11 with clear explanations

and alternatives provided for exceptional cases. This kind of functionality will have implications for the interfaces between the front-end electronic service sites and the back-end databases, processes, and infrastructure. (See Chapter 3 for more on technological considerations.)

In general, the maintenance of multiple channels should not preclude the transformation needed to provide services comparable with those of a large-scale financial services institution—such institutions maintain multiple channels themselves. As described in Chapter 4, e-government will eventually become simply “government” (and, accordingly, electronic services should simply be thought of as “services”).

FINANCIAL INSTITUTION WEB SITE DESIGN

Web Design Principles

It is not accidental that the top financial sites are alike in many ways, and it is not due to one’s copying another; this is an industry in which every participant expends great energy differentiating itself from its competitors. There are no hard-and-fast rules for the “best” design for a bank or brokerage site. However, a set of common principles has emerged, in addition to those standards and best practices codified by organizations such as the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). These principles, relating to simplicity, navigation, and accessibility, are described below. Most of the companies’ design processes incorporate significant user input and an understanding of appropriate usability mechanisms and techniques—this drives similarity in information architecture and navigation.

Relevance for the SSA and Other Agencies

Universal design principles should be applied to Web sites and usability testing should be made a routine part of the design process.12 Before sites face actual users, it is imperative to adopt user-centered design methods in which the needs and constraints of users are taken into account at all stages: that is, in design, development, deployment, requirements analysis from user perspectives, user participation in the design process, and user testing.

In addition, careful analysis about what kinds of services are most analogous to those offered by financial services institutions (and what are not) will be needed. Where sufficient similarity is found, not everything

needs to be tested; many of the most common practices in industry can be assumed to be the current best practices. Care must be taken, though, not to assume that the customer bases are necessarily similar; demographics and user expectations of the SSA user base may differ in subtle ways from those of major financial institutions, requiring attention when designing interfaces. Appropriate attention to standards and best practices articulated by Web standards organizations such as the W3C may also be helpful. Of particular importance is the need to avoid the assumption that everyone uses or has access to one or a small number of browsers. In general, as more is learned about how people interact with the Web and as the ways that people interact with Web sites change, the standards and best practices for the design of effective and usable Web sites will change. The SSA Web site’s design will need to evolve as the best practices and standards evolve.

Navigation and Simplicity

Any effective financial services site will have uncluttered pages with clear emphasis on the most common and natural transaction at each step. Achieving effective simplicity can be a more subtle challenge than one might think at first. In the case of basic Web design principles, counting the number of clicks to a transaction was once the core metric applied. This metric led to much “busier” pages and more choices at each step. This way of measuring simplicity has been relegated to a secondary measure, primarily for the following reasons:

-

Considerably-more-complex pages are tolerable for users whose Internet access speeds have improved (owing to increasing penetration of broadband access and high-speed Internet access from the workplace, libraries, or other institutions);

-

New technologies that allow pages to be dynamically updated eliminate the need for a complete page refresh; and

-

Users have become more sophisticated.

Simplicity also applies to visual clutter; if the eyes cannot find what they are looking for among things too similar to each other, then the user is likely to fail. Having good graphical design, putting similar things near each other, using wording that is clear—all lead to successful designs. An additional simplifying feature, from the user’s perspective, is for the back end to be flexible and robust in terms of how it handles data. Many Web sites distinguish themselves by both being maximally flexible in the syntax that they accept (for instance, telephone numbers may be entered with or without blanks, dots, or hyphens) and maximally consistent in the

syntax that they produce (for instance, always exhibiting telephone numbers consistently broken down into area code, exchange, and subscriber number separated by hyphens). An emphasis on robust data handling and presentation—accepting anything reasonable but always producing a canonical form—can achieve a huge improvement in data quality and in user experience while the user is entering data.

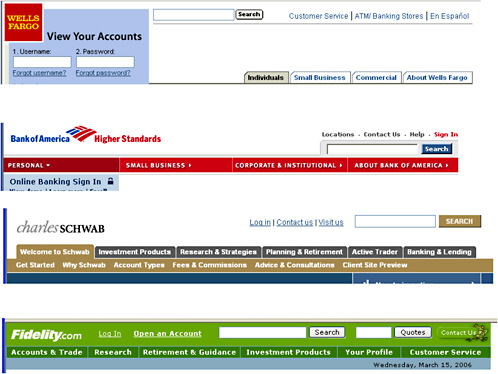

A navigational norm has emerged, consistent with many other commercial sites. If a single domain name serves multiple natural audiences, the navigation bar at the top allows users to indicate what type of customer they are and/or what services they are interested in (see the first two examples in Figure 2.1). Alternatively, they may navigate by type of product or service they are seeking (see the second two examples in Figure 2.1).

Common elements on the sorts of sites illustrated in Figure 2.1 are “search” and “log-in.” The log-in function is the gateway between the authenticated and unauthenticated parts of the site. For virtually all modern financial sites, the user experience (look and feel, navigation) is the same whether one is on the authenticated or unauthenticated part of the

FIGURE 2.1 Examples of typical commercial navigation styles.

site. Although the technology behind sites can be quite different, that distinction is designed to be transparent to the user.

There is less consistency than ever in the use of underlining for links. This was a virtual requirement in good design 10 years ago, but that is no longer the case. Through extended use of the Internet, along with acclimatization to interaction online, users have learned to recognize other cues, now expecting nearly everything except paragraphs of text to be a link. The use of underlining for link-intensive pages or sections of pages causes visual clutter and reduces readability.

Relevance for the SSA and Other Agencies

As a simplifying measure and as a way to emphasize a service orientation, content on the Web site regarding the agency itself (as opposed to the services that it offers) might be placed in a section subordinate to material that emphasizes services at the top level. A navigation bar should be composed of “parallel” items in some dimension. “Search” should have a text-input box. It is particularly important to understand the primary modes of use represented by those who will visit this Web site and to design labels suited to those individuals: for example, “Newly Retired,” “Checking Benefits,” or “Are You Ready to Retire?”13

Accessibility

All well-designed financial services sites are developed to be “accessible” to the visually impaired, in the technical sense of their information or content pages being W3C accessibility compliant14 and thus navigable by a screen reader (such as Job Access with Speech, or JAWS15). That is more challenging for the transactional portions of sites, but progress has been made there in the past 5 years.

Relevance for the SSA and Other Agencies

The SSA Web site, as well as other government Web sites, is expected to be at least Section 508 compliant; the SSA should ensure that all internal

|

13 |

Among government portals, FirstGov.gov offered an example of a reasonably effective use of usage-mode-oriented parallelism in the way that it presents its options. |

|

14 |

See World Wide Web Consortium, Web Accessibility Initiative, “Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0 (WCAG 2.0) Working Draft,” Nov. 23, 2005, at http://www.w3.org/WAI/, accessed June 20, 2007. |

|

15 |

JAWS (Job Access with Speech) is a screen reader for the visually impaired. See http://www.freedomscientific.com/fs_products/JAWS_HQ.asp, accessed June 20, 2007. |

and external applications are also compliant with Section 50816 and, to the extent possible, with other accessibility guidelines (such as those developed under the auspices of the W3C17). The SSA has a particular interest in accessibility given that it serves the disabled community explicitly. As more sophisticated electronic services are made available, maintaining accessibility will be important going forward, especially given the broad, diverse, and heterogeneous user base of the SSA.

CUSTOMERS AND USERS OF ONLINE SERVICES

Over 90 percent of U.S. households maintain a “transaction account” (such as a checking account, bill-paying account, or share draft account) with a bank, thrift institution, or credit union.18 Nearly all of these institutions offer online capabilities to their customers, and almost half of their customers make use of some or all of these services.19

Getting to these levels of penetration has taken 10 years of sustained and focused effort across the industry.20 Banking customers in the United States, even those most devoted to the online channel, remain largely “multichannel,” with consumers making use at the very least of a bank’s

|

16 |

Per the Web site http://www.section508.gov (accessed June 14, 2007), “In 1998, Congress amended the Rehabilitation Act to require Federal agencies to make their electronic and information technology accessible to people with disabilities. Inaccessible technology interferes with an individual’s ability to obtain and use information quickly and easily. Section 508 was enacted to eliminate barriers in information technology, to make available new opportunities for people with disabilities, and to encourage development of technologies that will help achieve these goals. The law applies to all Federal agencies when they develop, procure, maintain, or use electronic and information technology. Under Section 508 … agencies must give disabled employees and members of the public access to information that is comparable to the access available to others.” |

|

17 |

See the Web Accessibility Initiative at http://www.w3.org/WAI/, accessed June 20, 2007. |

|

18 |

In 2004, the Federal Reserve Board found that 91.3 percent of families hold transaction accounts. See Brian K. Bucke, Arthur B. Kennickell, and Kevin B. Moore, “Recent Changes in U.S. Family Finances: Evidence from the 2001 and 2004 Survey of Consumer Finances,” Federal Reserve Bulletin, Vol. 92, February 2006, pp. A1-A38 (Table 5), available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/oss/oss2/2004/bull0206.pdf, accessed July 10, 2007. |

|

19 |

Ted Schadler, Charles S. Golvin with Jed Kolko, Sally M. Cohen, and Tenley McHarg, “The State of Consumers and Technology: Benchmark 2005” in Forrester, Consumer Technographics North America, available at http://www.forrester.com/go?docid=36987, accessed June 14, 2007. |

|

20 |

The experiments in so-called online banks that allow only online interaction peaked in the bubble years of 1999-2001. Of these, Wingspan and First Security were ultimately unsuccessful, for example. Although some, such as NetBank, have survived, their impact on the industry has thus far been negligible in the United States. There are, however, some special cases, such as institutions offering above-market certificate of deposit rates, where online-only institutions (such as ING) are beginning to gather substantial deposits. |

ATMs for cash and check-deposit needs, and more generally remaining at least occasional users of branches and call centers.

The retail brokerage industry serves a smaller client base. The majority of brokerage accounts are with “lower cost” brokers, formerly known as “discount” brokers, such as Charles Schwab, Fidelity, E*Trade, and Ameritrade. Nearly all customers of these brokers, as well as a majority of clients of the traditional “wire houses” (such as Merrill Lynch) have sophisticated online capabilities. Trading online has become the default execution method; adoption of online services has transformed the retail brokerage industry.

Relevance for the SSA and Other Agencies

Much of the financial services industry, which previously relied heavily on paper-based transactions for customer interactions, has shifted large proportions of its interactions with consumers online. Certain market segments, primarily those early adopters with more income, education, and computer-savvy, are both comfortable and experienced with e-commerce. As a result, they should be comfortable with e-government transactions—even those involving their benefits—because they have already completed analogous transactions online with private-sector financial institutions. Looking ahead to the kinds of services that might be expected in the future, these same users might also value being able to understand their complete financial picture online if the financial services industry had the capacity to display information from the SSA as part of users’ financial profiles without rekeying the data—albeit such a service raises the usual privacy and security considerations.

BUSINESS INCENTIVES FOR ONLINE SERVICES

Banks and brokerages have made significant investments in developing their online service channels. One motivation has been that the cost per transaction differs greatly among service-delivery channels. The business case for doing so is composed of multiple elements: customer satisfaction, customer retention, acquisition of new customers, cross-sales of other products to existing customers, and the economic trade-offs between cost reduction and the cost of delivering online services.

Customer Satisfaction

A solid set of well-designed online capabilities improves customer satisfaction. In the past 10 years there has been ever-increasing focus on customer satisfaction as the financial services industry has consolidated

and personal relationships with local bankers have been replaced by interactions with megabanks. In the leading institutions, customer satisfaction is carefully measured and tracked. These banks can therefore measure the impact of online capabilities through matched samples of online customers versus customers using other service channels (though finding that control group for predictive purposes becomes more difficult as online usage becomes increasingly ubiquitous). Although the banks’ findings are proprietary, in general the results are thought to be very positive, with customers who conduct much of their business online showing significant improvements over time in their overall view of the banks.

Relevance for the SSA and Other Agencies

Appropriate measures of customer satisfaction require data from individuals using all of the agency’s service channels. This means that a representative sample of all individuals who interact with the agency, whether by phone, in an office, or online, should be consistently surveyed on a few simple measures of service satisfaction. One important observation is that the effectiveness of electronic services should be determined by measuring relative overall satisfaction of the users of online services as compared with the satisfaction of the remaining population of individuals using phone or office interactions (as opposed to measuring “satisfaction with online service” by itself). Note that the topic of customer satisfaction addressed in this subsection is only one of the many reasons for encouraging the use of electronic services—others include efficiency, accuracy and improved error rates, and convenience.21 Monitoring customer satisfaction as part of an overall metrics-based approach (see Chapter 4) to service provision can aid in encouraging the use of electronic services and in retaining users for that channel.

Customer Retention, New Customer Acquisition, and Marketing

Most Americans inevitably turn to the SSA at key points in their lives. Therefore, the SSA does not need to “acquire” new customers or “retain” them in exactly same way that a commercial concern would seek to attract new customers and keep its customers from switching to a competitor. However, the advantages that can be gained by the SSA and the public

|

21 |

A 2006 OECD paper proposing an inventory of business case indicators for e-government initiatives noted both reductions in benefits mispayments and in savings efficiency from both time savings for public servants and reduced error rates and rework. OECD E-Government Project, Proposal for Work on an Inventory of E-Government Business Case Indicators, Feb. 6, 2006, available at http://webdomino1.oecd.org/COMNET/PUM/egovproweb.nsf/viewHtml/index/$FILE/GOV.PGC.EGOV.2006.3.doc, accessed January 4, 2007. |

through wider use of electronic services do create motivation for the SSA to try to acquire and retain users in electronic channels of service delivery. Toward that end, the learning curve of commercial financial institutions can be informative for the agency.

The effect of online services on retaining existing customers has been the most compelling element of the case for introducing, expanding, and encouraging the use of these services. The rule of thumb in the banking industry is that it costs two to four times as much to acquire a new customer as it does to retain an existing one; in addition, the revenue generated by a new customer is often significantly less than the one they “replace.” Retention, therefore, is a key operational metric in any financial institution. The search for “sticky” products or services has been a long one, and none has succeeded like online access and—particularly, and quite dramatically—like online bill payment.

In contrast, online service offerings in retail banking have not had a dramatic impact on acquiring new customers. This is due to two countervailing forces. In the early years of online banking (1996 through 1999), there was significant differentiation among banks regarding their online offerings, but the demand for those offerings was quite low. In recent years, demand has increased dramatically, but now virtually every bank offers online access. Certainly the quality of the online services varies substantially, but that is apparent only to actual users of the services and much less so to those “shopping” for a bank. By contrast, in the retail brokerage industry, the situation is dramatically different. New entrants (with E*Trade and Ameritrade being the principal survivors) and more nimble “discount” brokers used their online expertise to draw in a whole class of new customers, as well as converting customers from the traditional “full service” wire houses.

The marketing of online services has taken multiple forms. For retail brokerages, as the bulk of their business has become e-business, virtually all of their marketing—whether print, television, or online—has placed their electronic services in the center of communications. For retail banks, marketing online services is one of the arrows in the communications quiver. It has become standard practice for banks to actively introduce and promote their online capabilities to new customers at the time of account opening, even if that takes place in the branch. For both the banking and the brokerage industries, one of the most effective means to convince customers to migrate to the online channel is to inform them politely at all other points of contact—for example, on the telephone or in person—that the particular transaction they are undertaking could be done more easily online (some banks even offer kiosks in their walk-in lobbies that facilitate online access to customer accounts). Brokerages now conduct the bulk of their transactions online; this may be partially due to the fact

that the demographics of users of brokerages are even more conducive to e-commerce adoption than are the demographics of users of banks.

Relevance for the SSA and Other Agencies

Although the SSA may not need to “acquire” new customers, it does need to attract them to—and retain them in—electronic channels. As noted earlier, having users’ needs met in the electronic services channel frees up resources for other users who need more-personalized service or responsiveness from other channels. This “stickiness” (retention) matters because the increasing use of an effective electronic channel will help the SSA keep costs down; it will mitigate shortages of in-person staff to handle the expected workload as the baby boom generation ages, becomes disability-prone, and retires; and it will likely increase public satisfaction with SSA information and services.

Public expectations for financial institutions with respect to functionality and availability are likely to translate to public expectations for electronic information and services from government agencies. At the same time, shortcomings will likely frustrate people and keep them in the more costly (and strained) delivery channels such as telephone calls and in-person visits. In addition, careful consideration of demographics and of particular market segments that are using electronic services at a high rate might lead the SSA to consider marketing to those segments very aggressively. There may also be lessons in how other government agencies have reached out to particular customer segments (see the discussion of the Internal Revenue Service in Chapter 4). Most importantly, the SSA needs to be able to promote the relative benefits of electronic services over the competing service channels in ways that are meaningful to users. The marketing needs to answer the question of, “What’s in it for me?” in a clear and compelling way.

Cross-Selling

Selling additional products or services to existing customers has generally been more successful through the online channel for financial services institutions. As compared with physical channels, the online experience more readily allows customers to appreciate the convenience of having “everything in one place”—even at a branch, a loan application might take place in a physical space different from where one makes a deposit; the online interface can hide even that sort of process separation. This drives the desire on the part of customers to consolidate their financial activities. In addition, a user of online services can be marketed to in a highly targeted way, at very low cost.

Relevance for the SSA and Other Agencies

Successful electronic services induce use of other available electronic services, potentially producing more effective and efficient service delivery overall. This improvement includes a reduction in data-entry error rates and the resultant costs of reworking to correct errors. Because of the relatively higher customer satisfaction scores for electronic services compared with telephone and paper processes, it stands to reason that a satisfied user of one e-government service will be more likely to seek out similar services to avoid long phone queues or paper-based cycle times.

Cost Trade-offs

Marginal costs of online transactions are very close to zero, and in any case much lower than any other means of delivery such as in person or by telephone. The fixed costs of building and maintaining online systems are significant, but the payback period—at least for the initial outlay—should be relatively short, even assuming that transaction volume remains the same. But, indeed, transaction volumes have tended to increase, as customers with online access have been observed to increase their overall use of services quite significantly. As these services have marginal costs that are close to zero, the costs incurred due to increased volume are outweighed by the savings due to the reduction in need for call center staff and IVR calls.

Relevance for the SSA and Other Agencies

As the SSA seeks to improve efficiency and migrate users to electronic channels, systematic cost tracking can help assess where additional efforts would prove fruitful. Such cost tracking should not be just at the aggregate level but instead should examine cost per transaction through a methodology such as activity-based costing. The effects of each service offered online with respect to call and office-visit volume could be systematically tracked as part of an overall effort to monitor appropriate metrics. Although the attribution of changes in call or office-visit volumes to the use of particular online services can be difficult, a standard and consistent methodology should be developed and agreed on. Items to be measured might include things such as costs per transaction, satisfaction, error rates, cycle times, repeat users by delivery channel, and so on. All of this should be done with a goal of maximizing value to users (taxpayers) and minimizing cost.

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES FOR ONLINE SERVICES

When considering e-business and electronic services generally, it appears that management and organizational structures for such services have had to proceed through three phases in the largest and most successful companies. In the first phase, which for most banks was approximately 1996 through 1998, there were multiple “e-groups” emerging in the organization. The primary focus for these services was often in marketing and communications organizations, as the chief use of Web sites was to market services rather than to provide them. In the second phase (approximately 1999 through 2002) “e-business” was paramount. Centralized, autonomous e-commerce lines of business—reporting very high in the organization—were formed with virtually end-to-end control of the e-channel. This seems, in retrospect, an almost necessary step to developing a sophisticated strategy, infrastructure, and set of policies for electronic service provision.

In the third phase, the current state of maturity (approximately 2002 to the present), the underlying approach appears to be “e-business is business” (see Chapter 4 for this committee’s presentation of the idea that now, or very soon, “e-government is government”). Although some of the largest and most successful institutions have kept a large e-group at the core, virtually every line of business and function has developed expertise to leverage the core assets. For example, organizational roles have tended to evolve along the following lines:

-

Centralized e-group: Strategy development, funding, navigation and information architecture, content ownership assignment, look and feel, policy development and enforcement, business requirements, storyboarding, wireframing, page design, sometimes front-end development;

-

Marketing and communications functions: Content for the “About” section, sign-off on the overall look and feel to fit the brand architecture;

-

IT function: Infrastructure, back-end and middleware development, sometimes front-end development; and

-

Lines of business: Content, business requirements for transaction services jointly with the core group.

Relevance for the SSA and Other Agencies

The SSA’s management and organizational structures for electronic services and e-government have not yet passed through the second phase described above. To track well with the maturing electronic services knowledge in the financial industry, in the second phase the development

and management of electronic services would be centralized and elevated in the organization.22 See Chapter 4 for more on this issue.

SUMMARY

In the future, the Social Security Administration will increasingly be viewed as a financial institution whose services are needed, and hence whose services will be expected to be available, on a 24/7 basis. Taking advantage of the experience of commercial financial institutions can help the SSA as it orients itself technologically and culturally toward weathering the oncoming storm of increasing workload, workforce transition, and changing public expectations. The commercial financial industry’s history of developing and marketing online services can provide the SSA with relevant experiences in the areas of adoption patterns, economic incentives, typical capabilities, Web site design, and organizational structure. Incorporating these lessons will require a strategic focus on electronic information and service delivery, metrics-guided improvement, and process transformation.

Finding: The experiences of large-scale financial institutions in transitioning to the provision of electronic services are instructive in considering the challenges faced by the SSA in formulating its medium- and long-term electronic services strategy.

Recommendation: The SSA should carefully consider the ways in which the experiences and approaches of large-scale financial institutions—including state-of-the-practice electronic information and service delivery, metrics-guided improvement, and process transformation, among other approaches and solutions—might be relevant to the kinds of services that the agency is providing or may provide in the future.