Summary

I.

INTRODUCTION

The Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program was created in 1982 through the Small Business Innovation Development Act. As the SBIR program approached its twentieth year of operation, the U.S. Congress requested the National Research Council (NRC) of the National Academies to “conduct a comprehensive study of how the SBIR program has stimulated technological innovation and used small businesses to meet federal research and development needs” and to make recommendations with respect to the SBIR program. Mandated as a part of SBIR’s reauthorization in late 2000, the NRC study has assessed the SBIR program as administered at the five federal agencies that together make up some 96 percent of SBIR program expenditures. The agencies, in order of program size, are the Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Health, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the Department of Energy, and the National Science Foundation.

Based on that legislation, and after extensive consultations with both Congress and agency officials, the NRC focused its study on two overarching questions.1

|

1 |

Three primary documents condition and define the objectives for this study: These are the legislation—H.R. 5667, the NAS-Agencies Memorandum of Understanding, and the NAS contracts accepted by the five agencies. These are reflected in the Statement of Task addressed to the Committee by the Academies’ leadership. Based on these three documents, the NRC Committee developed a comprehensive and agreed-upon set of practical objectives to be reviewed. These are outlined in the Committee’s formal Methodology Report, particularly Chapter 3, “Clarifying Study Objectives.” National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2004, accessed at <http://books.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=11097#toc>. |

First, how well do the agency SBIR programs meet four societal objectives of interest to Congress? That is: (1) to stimulate technological innovation; (2) to increase private-sector commercialization of innovations; (3) to use small business to meet federal research and development needs; and (4) to foster and encourage participation by minority and disadvantaged persons in technological innovation.2 Second, can the management of agency SBIR programs be made more effective? Are there best practices in agency SBIR programs that may be extended to other agencies’ SBIR programs?

To satisfy the congressional request for an external assessment of the program, the NRC analysis of the operations of the SBIR program involved multiple sources and methodologies. A large team of expert researchers carried out extensive NRC-commissioned surveys and case studies. In addition, agency-compiled program data, program documents, and the existing literature were reviewed. These were complemented by extensive interviews and discussions with program managers, program participants, agency “users” of the program, as well as program stakeholders.3

The study as a whole sought to understand operational challenges and to measure program effectiveness, including the quality of the research projects being conducted under the SBIR program, the challenges and achievements in commercialization of the research, and the program’s contribution to accomplishing agency missions. To the extent possible, the evaluation included estimates of the benefits (both economic and noneconomic) achieved by the SBIR program, as well as broader policy issues associated with public-private collaborations for technology development and government support for high technology innovation.

Taken together, this study is the most comprehensive assessment of SBIR to date. Its empirical, multifaceted approach to evaluation sheds new light on the operation of the SBIR program in the challenging area of early-stage finance. As with any assessment, particularly one across five quite different agencies and departments, there are methodological challenges. These are identified and discussed at several points in the text. This important caveat notwithstanding, the scope and diversity of the study’s research should contribute significantly to the understanding of the SBIR program’s multiple objectives, measurement issues, operational challenges, and achievements.

|

2 |

These congressional objectives are found in the Small Business Innovation Development Act (PL 97-219). In reauthorizing the program in 1992 (PL 102-564), Congress expanded the purposes to “emphasize the program’s goal of increasing private-sector commercialization developed through Federal research and development and to improve the Federal government’s dissemination of information concerning small business innovation, particularly with regard to women-owned business concerns and by socially and economically disadvantaged small business concerns.” |

|

3 |

The Committee’s methodological approach is described in National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology, ibid. For a summary of potential biases in innovation survey responses, see Box A in Chapter 3 of this report. |

II.

OVERVIEW OF THE NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION’S SBIR PROGRAM

This report addresses the SBIR program operated by the National Science Foundation (NSF), which annually makes several hundred awards that total nearly $100 million. The NSF focuses on supporting research and education at the nation’s universities. Nonetheless, it was the first federal organization to create a small business innovation research program. Roland Tibbetts is credited with creating the SBIR concept with a program for small business. Initiated, in 1977, it provided a model for the government-wide SBIR program launched in 1982. This precursor program was designated as the NSF’s SBIR program in 1982.

The NSF’s SBIR program has a number features that help distinguish it from the programs of other agencies. Unique features pertain to its history, size, mission and technology orientation, constituency, grant options, as well as its management and culture. These features are highlighted and elaborated below.

|

Box A Special Features of the NSF’s SBIR Program History: The NSF recognized early on that small businesses—like universities—can perform high quality, innovative research, and it developed the precursor of the SBIR program. Program Size: With its nearly $100 million in annual grants, the NSF operates the smallest of the five large SBIR programs. Mission: The NSF does not have a procurement mission; the program is oriented toward the private marketplace, but many of the technologies it funds also support other agency needs. Technology Orientation: The program provides early-stage support for diverse technologies, including manufacturing and materials research. Constituency: Rather than a single constituency, such as firms in aerospace or medicine or defense, the NSF has a broad constituency that cuts across industrial sectors. Supplemental Grant Options: As an innovation, the program added Phase IIB grant supplements following a Phase II grant conditional on attraction of third-party financing.a Program Management: The program is highly centralized, managed by staff with industry experience. Culture: The NSF has a growing culture of program analysis, experimentation, and evaluation. |

TABLE S-1 Number of NSF SBIR Grants, 1992-2005

|

Year |

Total Awards |

Phase I |

Phase II |

Phase IIB |

|

1992 |

265 |

208 |

57 |

0 |

|

1993 |

308 |

256 |

52 |

0 |

|

1994 |

330 |

309 |

21 |

0 |

|

1995 |

349 |

301 |

48 |

0 |

|

1996 |

342 |

252 |

90 |

0 |

|

1997 |

383 |

261 |

122 |

0 |

|

1998 |

336 |

215 |

117 |

4 |

|

1999 |

346 |

236 |

89 |

21 |

|

2000 |

337 |

233 |

95 |

9 |

|

2001 |

324 |

219 |

91 |

14 |

|

2002 |

392 |

286 |

67 |

39 |

|

2003 |

538 |

437 |

77 |

24 |

|

2004 |

397 |

244 |

131 |

22 |

|

2005 |

309 |

149 |

132 |

28 |

|

SOURCE: NSF SBIR program. |

||||

The NSF’s highly centralized SBIR program places substantial emphasis on the goal of commercialization. In recent congressional testimony, NSF SBIR officials said the program’s primary focus is “the commercialization of research.”4 This study, however, considers the program’s performance across three additional goals—stimulating technological innovation, using small business to meet federal research and development needs, fostering participation by minority and disadvantaged persons—as well as increasing private-sector commercialization of innovation.

Table S-1 shows the total number of NSF SBIR grants annually, as well as the number of each of the three types of SBIR grants: Phase I, Phase II, and Phase IIB. Between 1992 and 2005, the total number of grants fluctuated between 265 and 538 per year, and averaged 354. Over the entire period, Phase I grants accounted for the largest share of the total number at 73 percent. Phase II grants accounted for 24 percent of the total number of grants, and Phase IIB grants, which were started in 1998, accounted for only 3 percent of the total number per year. The three types of grants are defined and described below.

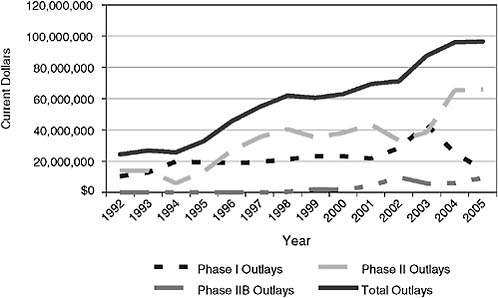

Figure S-1 shows the dollar amounts. In recent years, total grants have approached $100 million per year, with Phase II grants comprising the largest share in most years.

An NSF SBIR Phase I grant currently averages approximately $100,000 and lasts for six months. A Phase II grant ranges up to $500,000 and lasts for a period

FIGURE S-1 Dollar Amounts of NSF SBIR Grants, 1992–2005 (Current Dollars).

SOURCE: Based on data provided by the NSF SBIR program.

of up to two years. The NSF pioneered the use of the Phase IIB grant, which allows a firm to obtain a supplemental follow-on grant ranging from $50,000 to $500,000 provided the applicant is backed by $2 of third-party funding for every $1 of NSF funding provided. The Phase IIB grant is seen as a tool for promoting commercialization. It yields a different allocation of funding than would result from allocating all Phase II funding according to the initial Phase II selection process.

The NSF funded between 14 percent and 21 percent of the 1,000 to 2,000 Phase I proposals received each year over the period 1994 to 2005. It funded between 17 percent and 61 percent of the several hundred Phase II proposals received each year over the same period, and between 41 percent and 61 percent in the last few years of this period.

Many of the small companies that have received the NSF’s SBIR program assistance have developed novel and promising technologies, new products for market, new processes, and new capabilities. The NSF recently identified a few of these companies and technologies as illustrative of companies with “big ideas” under development. The NSF SBIR-funded technologies of these companies range from educational and medical tools, to nanoengineered powders for environmental cleanup, to new algorithms for improving information searches, to new devices for converting low levels of radiation into electricity.

III.

SUMMARY OF KEY FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Findings

The core finding of the study is that the SBIR program is sound in concept and effective in practice. It can also be improved. Currently, the program is delivering results that meet most of the congressional objectives. Specifically, the program is:

-

Stimulating Technological Innovation

-

Generating Knowledge. SBIR is contributing to the nation’s storehouse of public scientific and technological knowledge. This knowledge is embodied in data, scientific and engineering publications, patents and licenses, presentations, analytical models, algorithms, new research equipment, reference samples, prototype products and processes, spin-off companies, “human capital” (greater know-how, expertise, etc.), and new capability for further innovative activity. Publications and patenting activity occur with considerable frequency.5

-

Creating and Disseminating Intellectual Capital. Extensive licensing activities of Phase II awardees attested to the fact that useful intellectual capital has been created and disseminated. For example, the NRC Phase II Survey showed one-fifth of Phase II projects reported they had reached licensing agreements with U.S. companies and investors, and another fifth reported they had ongoing negotiations with U.S. companies and investors on licensing agreements.

-

Building Networks with Universities. Both the NRC surveys and the case studies showed extensive networking between NSF SBIR-funded projects and universities. University faculty and students used the NSF SBIR program to establish businesses, start projects, and work on projects.

-

Moving Technology from Universities Toward the Market. The NSF SBIR program has facilitated technology transfer out of universities. Fourteen percent of the NRC Phase II Survey projects were based on technology originally developed at a university by a project participant. Five percent of NSF Phase II Survey projects were based on technology licensed from a university.

-

|

5 |

The NRC Phase II survey reported averages of 1.66 scientific publications and 0.67 patents per surveyed project. See Table 7.2-1 in Chapter 7, Section 2, for additional survey information on the NSF’s SBIR program. The underlying distribution of patents and publications reported is skewed, with some companies reporting none and some reporting relatively high numbers. |

-

Increasing Private-Sector Commercialization of Innovations

-

Achieving Commercialization. Despite the fact that the agency itself normally does not acquire the results of SBIR-funded projects, a significant portion of NSF’s SBIR projects commercialize successfully or are making progress toward commercialization. For example, one-fifth of survey respondents indicated that their project had resulted in products, processes, or services that were in use and still active. A little more than a quarter of respondents indicated that the project was continuing technology development in the post-Phase II period. Of course, few individual SBIR projects lead directly to “home runs” in the commercial sense. Nonetheless, the NRC Phase II Survey shows that small firms believe that the NSF’s SBIR program helped them to enter commercial markets.

-

Project Initiation. The SBIR awards play a significant role in initiating the development of technologies and products that are subsequently commercialized. When asked if their companies would have undertaken the projects had there been no SBIR grant, approximately two-thirds of respondents answered either probably not (43 percent) or definitely not (24 percent).

-

A Small Percentage of Projects Account for Most Successes. As is typical for other private and public technology programs, a relatively few projects account for the majority of sales and licensing revenue from NSF SBIR recipients.6 This highly skewed performance distribution among projects is an inherent characteristic of early-stage investment—one that is impossible to avoid if innovation is to be promoted.

-

-

Using Small Businesses to Meet Federal Research and Development Needs

-

Mission Alignment. The NSF’s SBIR program funding is closely aligned with the agency’s broader mission and is contributing broadly to federal research and development procurement needs.

-

Meeting Agency Procurement Needs. The NSF SBIR program helps

-

-

-

to meet the procurement needs of federal agencies. The NRC Phase II Survey found that sales of NSF Phase II–funded technologies go to multiple markets with broad and diversified customer bases.

-

-

Fostering Participation by Minority and Disadvantaged Persons in Technological Innovation.

-

Open to New Entrants. SBIR has a high proportion of new entrants each year, rising to nearly two-thirds in 2003. Overall, between 1996 and 2003, 54 percent of the Phase I grants went to new entrants. Only 9 percent of selected firms had previously received more than 20 Phase I grants.7

-

Participation Rates of Women and Minorities. Women and minorities also participated in projects as principal investigators, with 21 percent of Phase II projects surveyed reporting either a woman, a minority, or a minority woman as the principal investigator. 8

-

Lower Success Rates. Success rates for woman- and minority-owned firms applying for Phase I awards are significantly lower than for other firms.9 Levels of participation by woman- and minority-owned businesses also continue to lag other groups. The cause of these lower participation rates is unclear. They may reflect the low representation of women and minorities in high technology firms.10 These lower suc-

-

|

7 |

See Table 4.2-8 and Figure 4.2-20. |

|

8 |

Analysis of data provided by NSF shows the number of Phase I proposals from and grants received by woman-owned businesses fell from 1994 through 2005. With the exception of a bump up in 2002 and 2003, there is no upward trend. The number of Phase II proposals from and grants received by woman-owned businesses from 1995 through 2005 exhibits no clear trend. Finally, the number of Phase IIB grants received by woman-owned businesses annually from 1998 through 2005 shows no obvious trend. See Chapter 4, Section 4.2.5, in this report for graphs of the data. |

|

9 |

From 1995 through 2005, woman-owned businesses submitted 12.2 percent of Phase I proposals and received 9.5 percent of Phase I grants. They submitted 8.8 percent of Phase II proposals and received 7.5 percent of Phase II grants. Minority-owned businesses (including minority women) submitted 16 percent of Phase I proposals and received 13.5 percent of Phase I grants. They submitted 12.9 percent of Phase II proposals and received 13.7 percent of Phase II grants. |

|

10 |

White males, who comprise 40 percent of the nation’s overall workforce, hold 68 percent of all science, engineering, and technology jobs. In contrast, white women, who comprise 35 percent of the national workforce, hold only 15 percent of these positions, and only 10 percent of the 2 million scientists and engineers in the United States in a recent year were women. African Americans and Hispanics, who comprise almost 21 percent of the American workforce, represent just 6 percent of the science, engineering, and technology workforce. (Congressional Commission on the Advancement of Women and Minorities in Science, Engineering and Technology Development. Findings of the Commission as reported in SSTI Weekly Digest, April 6, 2001; and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.) However, it should be noted that not all minority groups have low representation in science, engineering, and technology fields relative to their representation in the U.S. population Indicative of shifting representation among minority groups, there was a strong increase during the 1990s in the percentage of doctorate degrees and jobs in science and engineering going to foreign-born individuals, |

-

-

cess rates may also reflect obstacles that women and minorities face in pursuing careers in science and engineering.11

-

An Innovative Program. The NSF’s SBIR program operates with a limited administrative budget and legislated limits on funds for commercialization assistance. Nonetheless, with a number of valuable supporting functions and innovative approaches (such as Phase IIB to commercialization), the NSF’s SBIR program office has made an impressive effort in developing a well-run program with a number of supporting functions and growing evaluation effort.

-

Professional Staff. The NSF’s SBIR program is generally effective in achieving its goals and has benefited from its strong, centralized management and talented program managers.

-

More Assessment Is Needed. It is important to recognize the inherent challenges of early-stage funding of high technology companies with new but unproven ideas. All projects will not succeed. Nevertheless, greater efforts to rigorously document and evaluate current achievements and the impact of program innovations could contribute to improved program output.

-

Recommendations

-

Improving Program Operations.

-

Retain Program Flexibility. First and foremost, it is essential to retain and encourage the flexibility that has enabled NSF SBIR program management to develop an innovative and effective multiphase program.12

-

Conduct Regular Evaluations. Regular, rigorous program evaluation is essential for quality program management and accountability. Accordingly, NSF program management should give greater attention and resources to the systematic evaluation of the program, supported

-

|

11 |

Academics represent an important future pool of applicants, firm founders, principal investigators, and consultants. Recent research shows that owing to the low number of women in senior research positions in many leading academic science departments, few women have the chance to lead a spinout. “Underrepresentation of female academic staff in science research is the dominant (but not the only) factor to explain low entrepreneurial rates amongst female scientists.” See Peter Rosa and Alison Dawson, “Gender and the commercialization of university science: academic founders of spinout companies,” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, Volume 18, Issue 4 July 2006, pages 341–366. |

|

12 |

See Recommendation I, Chapter 2. |

-

-

by reliable data, and should seek to make the program as responsive as possible to the needs of small company applicants.13

-

Improve Processes. The NSF should ensure that solicitation topics are broadly defined and that the topic definition process is bottom-up, and take steps to ensure the necessary flexibility to permit firms to receive relatively prompt access to Phase I solicitations. Finally, the NSF should increase its use of technically competent reviewers with strong technical expertise and strong business understanding for both Phase I and Phase II selection.14

-

Increase Management Funding for SBIR. To enhance program utilization, management, and evaluation, consideration should be given to the provision of additional program funds for management and evaluation. Additional funds might be allocated internally within the existing NSF budget, drawn from the existing set-aside for the program, or by increasing the set-aside for the program, currently at 2.5 percent of external research budgets. The NSF spends some $100 million a year on SBIR, and the return on this investment could be enhanced with a modest addition to funds for management and evaluation.15

-

-

Continue to Increase Private-Sector Commercialization.16

-

Support Commercialization Assistance. The NSF should increase support for commercialization assistance as resources permit.

-

Encourage Continued Experimentation. The NSF should continue to promote its positive initiative with Phase IIB awards, refining the tool as experience suggests and raising the number and amount of these awards as third-party funding permits.

-

-

Improve Participation and Success by Women and Minorities.17

-

Encourage Participation. The NSF should develop targeted outreach to improve the participation rates of woman- and minority-owned firms, and strategies to improve their success rates based on causal factors determined by analysis of past proposals and feedback from the affected groups.

-

Improve Data Collection and Analysis. The NSF should arrange for an independent analysis of a sample of past proposals from woman-and minority-owned firms and from other firms (to serve as a control group). This will help identify specific factors accounting for the lower

-

-

-

success rates of woman- and minority-owned firms, as compared with other firms, in having their Phase I proposals granted.

-

Extend Outreach to Younger Women and Minority Students. The NSF should immediately encourage and solicit women and underrepresented minorities working at small firms to apply as principal investigators (PIs) and senior co-investigators (Co Is) for SBIR awards and track their success rates.

-