6

Support to Agency Mission and to Small Business

6.1

AGENCY DIFFERENCES: CONTRACTING VERSUS GRANT AGENCIES

Hearings surrounding passage of the SBIR-authorizing Act emphasized procurement barriers to small companies, with attention focusing on the large procurement agencies. In the then-existing environment, procurement agency proposals were said to be often too long and large for small businesses to undertake; projects were often bundled into packages too large for small businesses; and small businesses lacked the close tie-ins with project managers, who tended to prefer established institutions. Large “mission” agencies reportedly made many noncompetitive grants.1

In the defense world, the lines between the agencies and the companies they engaged were often blurred. This blurring of lines may have stemmed from the historical need of the military to control its supply of armaments and related goods. In contrast, from the beginning of its interactions with small business, there were very clear lines of distinction between the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the companies it engaged. The newly established Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program’s emphasis on agency procurement did not fit the NSF model, which is perhaps paradoxical given that the NSF program is considered the first SBIR program.

The focus on innovation by the new, multiagency SBIR program did, however, closely match the attention to innovation of the NSF’s predecessor program, though its motivation differed. The NSF’s emphasis was on adhering to scientific

excellence while countering an institutional bias in favor of funding academic research. In contrast, the new multiagency SBIR program was focused on rectifying the large disparity in research capability of large versus small firms, stemming in part from federal procurement practices.

Federal procurement of research and development carries with it the “independent research and development and bid and proposal expense” (IR&D/B&P) that provides firms with funds that they can use for independent research. “The 100 or so major defense contractors accounted for an estimated 97 percent of all IR&D.”2 The IR&D/B&P funds had primarily assisted large defense contractors in doing research that might lead to additional government contracts and, in the process, lessened the relative competitiveness of smaller firms lacking these funds for research. The SBIR program was seen as providing a way for the major procurement agencies to increase the capability of small businesses to also conduct research that might lead to federal procurement. Increasing the research capabilities of small businesses was seen as a way to decrease barriers to their entry into the defense contracting world and thereby to increase competition among agency vendors. In contrast, it was seen as a way for the NSF to fund innovative research in small firms for the purpose of generating technology that increases national economic prosperity, one of the NSF’s mission goals.

6.2

NSF—A NONPROCURING AGENCY

The NSF is an independent federal agency created “to promote the progress of science; to advance the national health, prosperity, and welfare; [and] to secure the national defense….”3 It is an important funding source for basic research conducted by the nation’s colleges and universities. In a number of disciplines, such as mathematics, computer science, and the social sciences, it is the major source of federal funding. The agency carries out its mission largely by issuing grants to fund specific research proposals selected through meritorious peer review. “NSF’s goal is to support the people, ideas and tools that together make discovery possible.”4

The NSF’s SBIR program follows the lead of the agency, emphasizing discovery and innovation that are put forward through a bottom-up process. Though the program defines topics, it defines them in ways that leave room for individual firms to decide what approach they will take. Its emphasis is on stimulating small firms to innovate, not on procuring goods and services that the agency needs.

The program encourages commercialization through the marketplace rather than through procurement channels. Unlike the defense agencies, the NSF would seldom be a customer for the results of its funded research. It was reportedly

|

2 |

Ibid., p. 127. |

|

3 |

“NSF at a Glance,” description of the agency provided at its Web site: <http://www.nsf.gov/about>. |

|

4 |

Ibid. |

clear to the program’s early developers from the outset that if the research results of funded projects were to be widely used, the use would have to come through avenues other than the agency’s procurement channels.5 Believing as they did that requiring companies to give attention to marketplace commercialization need not compromise the quality of research, the program designers were free to emphasize marketplace commercialization as a way to increase the economic impact of the agency’s new initiative.6

In summary, the driving force for the NSF’s SBIR program was to channel funding for innovative research to small firms for the purpose of generating a broad economic payoff, as a departure from funding only academic research. The driving force for the “mission” agencies’ SBIR programs was both to rectify the large disparity in research capability of large versus small firms, stemming in part from past federal procurement practices, and to increase procurement options for the agencies. However, the resulting program parameters were closely similar: agency grants were to be made to small businesses for innovation, and commercialization—defined broadly to encompass sales into the marketplace, agency procurement, and subcontracts and sales to prime contractors—was to be encouraged.

6.3

NSF SUPPORT OF SMALL BUSINESS

6.3.1

Basic Demographics of NSF Support for Small Business

The NSF’s funding for universities dwarfs that to small businesses. Its support for small business is centered in its SBIR/STTR [Small Business Technology Transfer] programs within the Office of Industrial Innovation (OII), and the SBIR program is much larger than the STTR program. Therefore, the demographics of the SBIR program, as summarized in Section 4.2, provide the principal demographics of NSF support for small business. In recent years, the NSF’s SBIR program has provided close to 300 awards annually, totaling nearly $100 million to small firms.

6.3.2

NSF Small Business Research Funding as a Share of NSF R&D Spending

While the SBIR program directs R&D funding to small businesses, it remains a small percentage of the total budget of the NSF. The congressionally directed

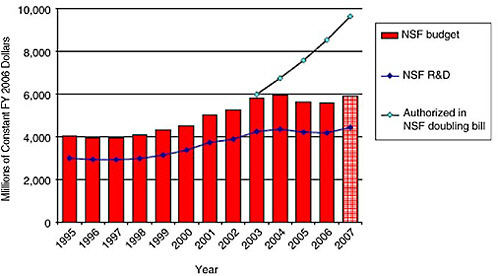

FIGURE 6.3-1 National Science Foundation Budget, FY1995–2007 (Budget authority in millions of constant FY2006 dollars).

SOURCE: AAAS.

NOTE: Authorized levels are authorizations in Public Law 107-368 (Dec. 2002). The solid line shows the portion of the NSF’s annual budget authority for the NSF’s R&D. Mlillions of Constant FY 2006 Dollars

expenditure on the SBIR program is 2.5 percent of the NSF’s extramural research budget. The largest part of the NSF’s budget by far goes to research and development by entities other than small businesses.

In FY2004, the NSF’s total budget for R&D was $4.1 billion, consisting of $3.8 billion for the conduct of research and $0.3 billion for R&D facilities.7 Figure 6.3-1 provides a look at recent trends in R&D funding at the NSF, which will be reflected in turn in funding available to the foundation’s SBIR program. In 2005 and 2006, the total current R&D budget is essentially flat, declining slightly in real terms, as shown by the solid line across the bars. In constant FY2006 dollars, the 2004 budget represented a peak, followed by a decline in 2005 and a further small decline in 2006, followed by an increase in FY2007.

Despite the fact that the NSF’s SBIR program is not procuring for federal requirements, the results of the NRC Phase II Survey showed customers of NSF-funded technologies to include federal agencies and primes. While slightly more than half of sales of NSF Phase II-funded technologies were reported to be going

|

7 |

American Association for the Advancement of Science, AAAS R&D Funding Update on NSF in the FY2007 Budget, available online at <http://www.aaas.org/spp/rd/nsf07hf1.pdf>. |

TABLE 6.3-1 Sales of NSF PII–Funded Technologies Go to Multiple Markets with a Broad and Diversified Customer Base

|

New and improved products to domestic civilian sector |

57% |

|

Meeting federal agency needs |

20% |

|

International competitiveness |

11% |

|

Support to universities and other institutions |

9% |

|

Meeting needs of state and local governments |

4% |

|

SOURCE: NRC Phase II Survey. |

|

to domestic civilian markets, as Table 6.3-1 shows, 20 percent were reported to be meeting federal agency procurement needs.

Other survey results show that the NSF’s SBIR program is enabling small firms in ways supportive of NSF’s mission. It is achieving a high level of participation by firms new to the NSF’s SBIR program each year. In 2003, the most recent year examined, more than 60 percent of grantees were new to the SBIR program. As described in more detail elsewhere in this report, it appears that the program is changing small firms’ conduct of R&D, enabling them to undertake projects they otherwise would not have, to broaden the scope of research, and to accelerate results.