4

Establishing Relationships Between Dietary Patterns and Health Outcomes

The complexities of diet and of diet-related diseases complicate nutritional risk assessment. This chapter covers information on the challenges in establishing relationships between food patterns and health outcomes, the use of evidence-based reviews for linking dietary factors with chronic disease outcomes, and the use of evidence-based reviews for evaluating health claims for use on food labels.

In introducing the session, Michael Doyle commented on risk assessments of Listeria monocytogenes, a microbial pathogen. Those risk assessments made it possible to prioritize the types of foods that are most important as vehicles for Listeria and that are thus targets for action to improve the public’s health. He expressed the hope that eventual outcomes of this workshop will be the ranking of risks and the engagement in other opportunities for advancing the nutritional aspects of food that could improve the public’s health.

CHALLENGES IN ESTABLISHING RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN FOOD PATTERNS AND HEALTH OUTCOMES

Presenter: Julie Mares

The relationships between diet and chronic disease differ in character from the relationships between diet and deficiency or between diet and acute disease, but the techniques available for evaluating them often do not reflect this. Using examples from her research on age-related macular degeneration (AMD), Julie Mares highlighted common and often overlooked sources of uncertainty that bias the interpretation of relationships

between diet and chronic disease and that often lead to the drawing of wrong conclusions. These involve (1) the complex and slowly developing nature of chronic disease, (2) the timing and broad nature of dietary influences on the development of chronic disease, and (3) the bias imposed by limitations inherent in specific study designs. Mares also suggested strategies that could be used to reduce the impacts of these biases to improve the interpretation of the long-term and complex relationships of diet to chronic disease. Delgado-Rodrigous and Llorca (2004) provide comprehensive coverage of the issues related to the internal validity of studies.

Relevant Features of Chronic Diseases

Chronic diseases typically develop in several stages, over long time periods, and in people who live a long time. Such diseases are multifactorial. Typically, they involve a number of pathogenic mechanisms; are influenced by one’s environment, lifestyle, and genetic attributes; and are associated with comorbid conditions.

In addition, the effects of nutrients may differ at different stages of a disease. In cancer, for example, the effects may differ during the initiation, promotion, and progression of the cancer. In AMD, the potential for a person to obtain the beneficial effects from the carotenoid lutein appears to relate to the stage of the disease. The current evidence that lutein and zeaxanthin (another carotenoid) reduce the risk of disease progression is stronger for the later stages of AMD than for the earlier stages.

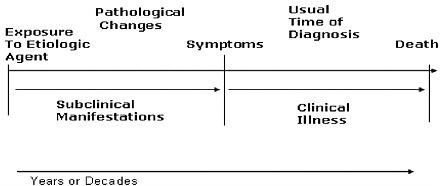

Chronic diseases develop over decades, as shown in Figure 4-1. Among people exposed to conditions that increase the risk, however, relative risks for many chronic diseases decrease with age. This apparent decrease in risk could reflect two factors: (1) the changing nature of the surviving cohort and (2) selective mortality bias. For diseases that strongly increase in prevalence with age (such as AMD) these two factors can reduce the apparent influence of protective factors.

FIGURE 4-1 Chronic diseases develop over decades.

Addressing Uncertainties Relating to the Influence of Diet

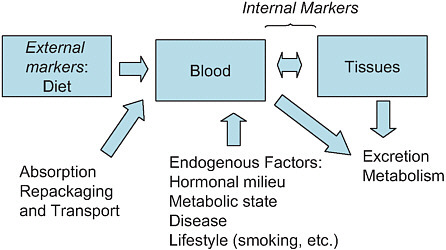

Investigators have used a variety of markers of dietary intake, including both external and internal markers. A number of factors may influence these markers, as shown in Figure 4-2. Mares called for the use of dietary intake as the anchor of all markers because it provides the opportunity to study many aspects of diet concurrently and because dietary intake estimates facilitate comparisons across studies.

Biomarker data are useful complements to the dietary data. Biomarker data can be used to circumvent errors in nutrient databases and inaccuracies in people’s reports of what they eat. Such data reflect influences on the absorption and turnover of a food component. A typical biomarker, such as the blood concentration of a nutrient or metabolite, reflects a single dietary constituent. Increasing evidence suggests, however, that the intake of other nutrients can modify the influence of any single nutrient. Therefore, the use of biomarker data to evaluate the relationship of diet to chronic disease is useful only when such data are complemented with measures of broad aspects of the diet, which can be obtained from detailed food frequency questionnaires.

Biomarkers reflect intake over a short time. Using data that reflect a few weeks of intake imposes a large error when relating the intake to a condition that develops over decades. The random error is compounded with bias in studies of middle-aged and older adults whose intakes change with time and also change in response to the presence of other chronic diseases that may increase risk for the disease being studied. (Cardiovascular disease, for example, may lead to dietary change and it

FIGURE 4-2 Types of markers of dietary intake and the factors affecting them.

increases the risk of AMD.) The result may be an apparent deleterious association between blood concentrations of a nutrient and the disease when, in fact, the nutrient is protective. That is, the analysis produces a completely wrong answer.

Diet–Time Period Relationships

The period during which diet is measured may have more of an impact on the precision of the estimate than the method used to measure the diet. Thus, the period covered by the measurement may bias the results. In estimating the odds ratios for the prevalence of AMD according to whether a person’s diet was high or low in saturated fat, for example, Mares-Perlman and colleagues (1995) observed that dietary assessment at the baseline gave odds ratio estimates very different from those obtained from retrospective estimates of the diet consumed 10 years earlier. For this reason, it is optimal to obtain multiple estimates of dietary intake over the time period that is expected to influence the development of the disease being studied. When this is not possible, it is better to collect retrospective estimates of dietary intake than to ignore the past diet altogether. Others have demonstrated that people’s recall of the diet that they

consumed a decade earlier is a better reflection of what they actually ate than their more recently recalled diet (Byers et al., 1987).

Changes in diet over time may introduce additional uncertainty. More than half of the population over the age of 65 years has three or more chronic diseases. Since chronic disease often influences diet, current dietary intake of older people may not reflect their diet over most of their adult lives. In a study that collected dietary data for two different periods, Moeller and coworkers (2006) computed multivariate-adjusted odds ratios for intermediate AMD among women whose diets were high and low in lutein and zeaxanthin. When the investigators compared women of all ages, they found lower odds ratios if they excluded women with unstable diets.

Other Factors That Affect the Influence of Diet on Disease

Other risk factors may modify the influence of diet. For example, people with poor diets may be lost from the cohorts being studied. In addition, the proportion of people who are susceptible to the influence of diet may change. For example, Ogren and colleagues (1996) found that among men born in 1914, 26 percent of smokers and 31 percent of those with hypertension at age 55 years died before the age of 68 years. Thus, the proportion of a surviving cohort with long-term chronic conditions can decrease with increasing age in a study sample.

Strategies to Enhance the Study of Diet and Chronic Disease

Both the splitting and the lumping of data can be useful in enhancing the study of diet and chronic disease, as described below.

Splitting of data Subgroup analyses, which involve the splitting of data, are important both within and across studies. Such analyses need to reflect the stage of the disease in the natural history of the disease, the time period in the natural history of the disease, the absence or presence of other risk factors, and the age of the individual or the presence of comorbid conditions. To evaluate these potential biases, one can evaluate the risk ratios across strata defined by age, disease severity, and the presence of other risk factors. This approach provides valuable information even if one does not detect statistically significant interactions of the

primary association. Mares calls for more attention to this issue in the publication of epidemiological associations in samples of people over 50 years of age.

Lumping of data The lumping (grouping) of data can be useful for assessment of the dietary attributes that influence similar pathogenic mechanisms. It can also be useful and efficient to lump several outcomes in each study.

Contributions of Different Study Designs

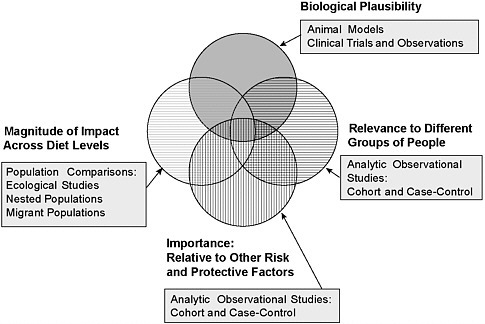

As depicted in Figure 4-3 and briefly discussed below, studies of different types can make a valuable contribution to the body of evidence used in nutritional risk assessment. Differences in findings from different types of studies offer an opportunity to find the reasons for those differences.

FIGURE 4-3 Uses of different types of studies in examining the body of evidence. The results of studies with different designs can contribute unique insights. The ability to make inferences about the causal influences of dietary attributes or patterns in the development of chronic disease is strengthened when all types of evidence point in the same direction.

Animal Models for Age-Related Chronic Diseases

Animal models for chronic disease either do not exist or are very limited. The models that are available often do not reflect various aspects of human disease, such as the natural history of the disease and environmental, medical, and dietary influences. Thus, investigators mainly rely on human studies to evaluate the impact of diet on human disease. Nevertheless, animal models may be useful for examining the biological plausibility of effects of particular dietary components or the synergy between two dietary components.

Observational Studies

Cohort and case–control study designs provide useful information about the relationships of diet to health, including the importance of diet relative to the importance of other risk- and protective factors among large groups of people. Other population comparisons and ecologic studies provide information about the impacts of a wide range of diets and conditions.

Randomized Clinical Trials

Clinical trials are useful for determining biological mechanisms and plausibility. Mares views randomized clinical trials as part of a toolbox rather than the “gold standard” for the collection of evidence. The applicability of the conclusions from such trials are often limited to single nutrients or groups of nutrients, the doses of the nutrient(s) given, the form of the nutrient(s) tested, the duration of treatment, and the characteristics (e.g., high or low risk) of the study population. Loss to follow-up can bias the findings of a study, and investigators often do not adequately evaluate this problem. Cost factors may preclude the testing of modifying factors, such as other aspects of the diet and a person’s genetic makeup, physical activity, lifestyle, and medical history.

Clinical trials complement results of observational studies. For example, the Rotterdam Eye Study showed that diets rich in the components of the supplements used in the Age-Related Macular Degeneration Study reduced the incidence of intermediate AMD by 35 percent (Van Leeuwen et al., 2005).

Mares listed several ways to improve the utility of clinical trials in the understanding of diet and disease, namely (1) the use of shorter, intermediary endpoints, especially those common to the development of many chronic conditions; (2) studies of the natural history of the disease; and (3) broader studies that address multiple dietary attributes. Examples of such studies include the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (Sachs, 2001) and the Mediterranean Diet used in the Lyon Heart Study (De Longeril, 1999).

Concluding Remarks

In closing, Mares encouraged investigators to take a bird’s eye view by observing more and by broadening trials:

-

Observe more by using multiple study designs, large or pooled data sets, diet estimation complemented with biomarkers, and subgroup analyses, with less concern about the statistical significance of interactions.

-

Broaden trials so that they study a variety of disease outcomes, especially intermediate stages that reflect biological mechanisms, and a variety of dietary attributes.

EVIDENCE-BASED REVIEW PROCESS TO LINK DIETARY FACTORS WITH CHRONIC DISEASE

Presenter: Alice H. Lichtenstein

The application of the evidence-based review process to matters of public health importance has been expanding. Alice Lichtenstein provided an overview of the evidence-based systematic review process and used omega-3 fatty acids to illustrate how this process can be a useful tool for addressing nutrition-related issues. The example, omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease (CVD), came from work conducted at Tufts-New England Medical Center under the auspices of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). AHRQ evidence reports and summaries are available at http://www/ahrq.gov/clinic/epcquick.htm.

Steps in the Evidence-Based Review Process

Many steps occur in the evidence-based review process, as summarized below:

-

Form a technical expert panel that includes stakeholders and the key people to guide the group.

-

Refine the key questions. This is the most important step in the process.

-

Identify search terms, using enough terms to identify all the relevant literature while minimizing extraneous articles.

-

Develop the inclusion and the exclusion criteria. Examples of such criteria include the minimum and maximum doses, the minimum number of subjects per study, the minimum information on the intervention required, and the basic criteria used for the study design.

-

Conduct the literature search by using predefined databases. This includes examination of the reference lists of reviews and primary articles and contact with domain experts to identify relevant articles missed by the database searches.

-

Screen abstracts for potentially relevant articles.

-

Retrieve the full articles selected.

-

Review the articles according to the predetermined criteria.

-

Extract data from the articles that meet the criteria. The PICO approach is useful for this step. It involves focusing on the population (P), the intervention (I), the comparator group (C), and the outcome (O).

-

Grade the studies for their methodological quality and applicability.

-

Develop data tables. These typically include (1) summary tables that present data on sample size, intervention, duration, results, and quality and (2) summary matrices that place studies in a grid based on methodological quality and applicability.

-

Perform additional analyses (e.g., a meta-analysis), as appropriate. Draft the report.

-

Send the report out for peer review.

-

Revise the report as needed.

Overview of an Evidence-Based Review: Omega-3 Fatty Acids and CVD

Two of the specific questions asked in the review of omega-3 fatty acids and CVD were:

-

What is the efficacy or association of omega-3 fatty acids in preventing incident CVD outcomes in people without known CVD (primary prevention) and with known CVD (secondary prevention)?

-

What adverse events related to omega-3 fatty acid dietary supplements are reported in studies of CVD outcomes and markers?

The PICO approach was used to address these questions, as follows:

-

The populations (P) covered subjects in studies of both primary prevention and secondary prevention.

-

The interventions (I) included alpha-linoleic acid in addition to eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).

-

The comparators (C) were diets and other oils (e.g., an oil in the placebo capsules, which might be an oil that could affect the results).

-

The outcomes (O) were all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, and sudden death.

Among the inclusion criteria that were used were experimental or observational studies of at least 1-year duration with at least five human subjects, with reported original CVD outcome data, and with all sources of omega-3 fatty acid intakes evaluated.

In this evidence-based review, the possible ratings for methodological quality were as follows: least bias, the results are valid (rating of A); susceptible to some bias but not sufficient to invalidate the results (rating of B); and significant bias, may invalidate the results (rating of C). The following ratings were used for applicability: the sample is representative of the target population (rating of I), the sample is representative of a relevant subgroup of the target population but not the entire population (rating of II), and the sample is representative of a narrow subgroup of subjects only and is of limited applicability to other subgroups (rating of III). The possible ratings of the overall effect were as follows: a clinically meaningful benefit was demonstrated (rating of ++), a clinically

meaningful beneficial trend exists but is not conclusive (rating of +), a clinically meaningful effect is not demonstrated or is unlikely (rating of 0), and a harmful effect is demonstrated or is likely (rating of −).

The overall conclusions were that the intake of omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA) from fish or fish oil supplements reduces the incidence of all-cause mortality and cardiac and sudden deaths but not stroke. The benefits of fish oil supplementation were greater in the secondary prevention studies than in the primary prevention studies. The adverse effects appeared to be minor, but data were limited and incomplete. That is, most studies either did not report on adverse effects or did not describe the tabulation method used.

Concluding Remarks

The conclusions drawn from systematic evidence-based reviews of relationships between dietary factors and chronic disease may differ. Divergences likely result from differences in the specific questions asked, the inclusion and exclusion criteria used, the statistical model used for analysis, and the quality rating system used. The process is challenging, in part because of the limited data available in the field of nutrition and human outcomes.

EVIDENCE-BASED REVIEW FOR HEALTH CLAIMS: A CASE STUDY

Presenter: Kathleen C. Ellwood

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is using an evidence-based review process as a basis for health claim language on food labels. Kathleen Ellwood provided background information on nutrition labeling and health claims, described the process for reviewing the scientific evidence, and summarized results from selected evidence-based reviews.

Background Information on Nutrition Labeling and Health Claims

The Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990 serves as the basis for the current food labels, including the provisions that allow voluntary nutrition claims on food labels; and it covers health claims when they are authorized by the FDA. Health claims on food labels serve as a way to inform consumers about the relationships between the substances (food or component in food) and a disease. The U.S. Congress set “significant scientific agreement”1 as the standard for substantiating health claims. As a result of court challenges under the First Amendment to the Constitution, the FDA was directed to provide for health claims that did not meet the significant scientific agreement standard. Qualified health claims are based on scientific evidence that is credible but that does not meet the higher standard.

Health claims are voluntary statements that address a causal relationship between a substance and either a disease or a health-related condition for the general U.S. population or for a subpopulation, such as women or the elderly population. The substance is to be able to reduce the risk of disease, not treat, prevent, cure, or mitigate a disease (Whitaker v. Thompson, 2004).

Process for Reviewing the Scientific Evidence

The process for reviewing the evidence for significant scientific agreement health claims and qualified health claims is the same; the level of supportive evidence distinguishes the two. In particular, the process involves the following steps (FDA/CFSAN, 2003b):

-

Define the substance–disease relationship.

-

Identify relevant studies.

-

Classify relevant studies.

-

Rate the relevant studies for quality.

-

Rate the studies for the strength of the body of evidence.

-

Report the rank.

Definition of Substance–Disease Relationship

The substance means a specific food or a specific component of a food in a conventional food or a dietary supplement (FDA, 2006a). The disease or health-related condition means “damage to an organ, part, structure, or system of the body such that it does not function properly (e.g., cardiovascular disease) or a state of health leading to such dysfunctioning (e.g., hypertension” [FDA, 2006b]).

Identification of Relevant Studies

Relevant studies include intervention and observational studies that involve healthy people and that measure the risk of the disease or health-related condition named in the claim. Animal and in vitro studies, review articles, meta-analyses, and book chapters are not relied upon. The last three types of sources, however, may be used to identify additional relevant studies. Intervention and observational studies with fatal flaws are excluded. Examples of such flaws are the lack of a control group or a nonvalidated surrogate endpoint in an intervention study and the exclusion of key confounders of risk in an observational study.

Classification of Relevant Studies

FDA considers intervention studies to be the “gold standard” and uses intervention studies that measure modifiable risk factors. Among the observational studies, prospective cohort studies are considered more reliable than case–control studies and cross-sectional studies. Two key elements of such studies are the measurement of the intake of the substance and the handling of factors (such as age and weight) that could confound the results.

Rating of Quality

The factors considered in rating the studies for quality include the study design and the inclusion and exclusion criteria used, the balance of population characteristics, verification of compliance, and the statistical methods used.

Rating of Strength of the Evidence

The factors used to rate the strength of the body of evidence include the types, quality, and quantity of studies; the study sample size; the consistency of the findings; replication of the findings; and relevance to the general population or target subgroup.

Ranking

Different levels of scientific evidence result in different qualifying language, as shown in Box 4-1. The qualifying language provided in the task force report (FDA/FSAN, 2003a) provides examples only; the language may vary depending on the specific circumstances of each case.

Results from Selected Evidence-Based Reviews

Lycopene/Tomatoes and Cancer

In 2004, FDA received two petitions requesting a large number of health claims for tomatoes, tomato products, and the carotenoid lycopene in relation to reduction in the risk of cancer. The petitions cited a large number of publications and websites. Through a literature search, the FDA identified additional publications. None of the intervention studies identified were credible because all evaluated the treatment of men diagnosed with prostate cancer. A review of the observational studies eliminated many studies. Of the 13 relevant observational studies evaluating the relationship between tomatoes or tomato products and prostate cancer, 6 indicated a reduction in risk and 7 reported no association. The prostate cancer claim language statement for food labeling is, “Very limited and preliminary scientific research suggests that eating one-half to one cup of tomatoes and/or tomato sauce a week may reduce the risk of prostate cancer.” FDA concludes that there is little scientific evidence supporting the claim.

|

BOX 4-1 INTERIM EVIDENCE-BASED RANKING SYSTEM FOR HEALTH CLAIMSa Significant Scientific Agreement Health Claim: high level of comfort (A) “ … may reduce the risk of … “ Qualified Health Claims

SOURCE: FDA/CFSAN, 2003a. |

Chromium Picolinate and Type 2 Diabetes

A review of the evidence identified five credible intervention studies of chromium picolinate intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes (T2D). Four of these studies showed no effect of chromium picolinate on blood sugar levels, and a single study showed a beneficial effect of chromium picolinate on insulin resistance. Qualifying health claim language in this case includes “a relationship between chromium picolinate and either insulin resistance or T2D is highly uncertain.”

Green Tea and Breast Cancer

A review of the evidence identified three credible observational studies relating green tea intake to the risk of breast cancer. Two of these were prospective cohort studies that showed no relationship, and one was a case–control study that showed a beneficial relationship. Qualifying health claim language in this case includes “it is highly unlikely that green tea reduces the risk of breast cancer.”

Concluding Remarks

Kathleen Ellwood encouraged participants to visit the FDA website for more detailed information on this topic.

OPEN DISCUSSION

Moderator: Michael Doyle

The key points made during the open discussion have been incorporated into Chapter 6, Perspectives on Challenges and Solutions: Summary Remarks and Suggested Next Steps.