6

Conducting Confirmatory Drug Safety and Efficacy Studies1

|

Recommendations on Public–Private Partnerships for Conducting Large Research Studies from the IOM Report The Future of Drug Safety: Promoting and Protecting the Health of the Public Recommendation 4.3 The committee recommends that the Secretary of HHS [Health and Human Services], working with the Secretaries of Veterans Affairs and Defense, develop a public-private partnership with drug sponsors, public and private insurers, for-profit and not-for-profit health care provider organizations, consumer groups, and large pharmaceutical companies to prioritize, plan, and organize funding for confirmatory drug safety and efficacy studies of public health importance. Congress should capitalize the public share of this partnership. |

The IOM report noted that the FDA is limited in its ability to conduct the larger studies sometimes necessary to follow up on signals and reduce uncertainty associated with the benefits and risks of approved drugs. Accordingly, the report recommended the development of public–private partnerships to prioritize, plan, and fund confirmatory drug safety and efficacy studies (Recommendation 4.3).

The ideas expressed in this session, particularly with respect to Recommendation 4.3, dovetailed with those put forth in the previous session, supporting the necessity of and readiness for a public–private collaborative effort to improve postmarket safety and efficacy monitoring. Whereas the focus of the previous session was on the capacity of a linked

public–private surveillance system to improve the detection of safety signals, panelists went a step further during this session by considering the potential of such a system to be used not just for detection, but also as a tool for addressing the broad spectrum of safety science research questions that arise over the course of a drug’s lifetime. A collaborative effort to this end would be more cost-effective than multiple isolated efforts, as presenters in the previous session emphasized with regard to detection. It would give researchers access to a larger volume of information resources, and it would generate information of value to multiple stakeholders.

Dr. Dieck elaborated on earlier discussions regarding the use of public–private partnerships for establishing and conducting active surveillance studies. While industry is interested in supporting such partnerships because of their potential to lower the costs associated with larger safety studies and provide better benefit–risk information, costly studies for specialized populations unlikely to be included in an automated, linked database would still be necessary. Such specialized postmarket safety studies are expensive, costing from $500,000 to $110 million (i.e., the Exubera VOLUME LST study).

Dr. Califf identified two fundamental changes necessary to establish a large public–private partnership to prioritize, plan, and organize funding for confirmatory drug safety and efficacy studies of public health importance. First, stakeholders need to be proactive and take responsibility for establishing such a partnership. These stakeholders include pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and medical device companies; government agencies (the Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], the National Institutes of Health [NIH], the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], and the Department of Veterans Affairs [VA]); private health plans; academic health centers (which have largely discouraged this kind of activity in the past); and consumer groups. Dr. Califf suggested that bringing these groups together would have not just an additive but a synergistic effect, particularly with regard to workforce standardization and interoperability. Second, it will be necessary to modernize the “incredibly inefficient” clinical research system to eliminate wasteful spending and build efficiency into the system.

Dr. Califf echoed statements made earlier by Drs. Krall and McClellan about what will happen if public–private partnerships and the associated lower costs are not achieved. If the various stakeholders developed their own systems, the resulting bureaucracy would be highly complex; moreover, it would be dangerous to have every health care organization publicizing results and making coverage decisions based on its own limited datasets. Dr. Califf suggested that the IOM conduct a study on the cost of developing such a partnership, hypothesizing that the total cost

would be less than the cost of having multiple separate entities, as argued by Dr. McClellan.

A public–private partnership would do more than save money, stressed Dr. Califf. Given the reality that every drug has both benefits and risks, along with the heterogeneity of individual responses, the system risks shelving good products in the absence of a systematic way of responding to and putting into context the signals detected by an automated surveillance system. A public–private partnership would minimize that possibility by setting priorities and, through consensus, deciding on the most important safety research questions. The partnership could also deal proactively with the design of studies intended to clarify putative safety signals. These studies could include larger surveillance studies, more focused prospective registries, pragmatic trials, or mechanistic laboratory-based studies to determine biological mechanisms. Dr. Califf proposed that industry be rewarded for prioritizing in the public interest, and that government agencies focus on prioritizing according to impacts on public health. The hope is that a public–private partnership would be nimble enough to respond to the needs of the public while avoiding the types of bureaucracy that create rules and expensive procedures with the expectation that “armies of people following processes” will lead to better research answers. Rather, the bureaucracy should be efficient, focused on standardizing data collection and nomenclature and optimizing the yield of useful research results per dollar spent. Failure to develop common data standards and controlled vocabularies would make it exceedingly difficult to combine datasets, which is critical to integrating databases.

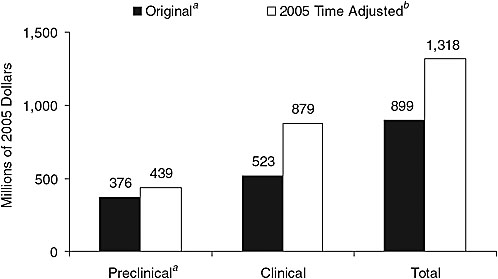

With respect to cost, Dr. Califf suggested that while a new system would require investment, much of the current $90+ billion being spent each year on biomedical research and development worldwide is being spent unnecessarily. He pointed to the 2005 time-adjusted estimated cost of drug development—$1.318 billion ($439 million preclinical, $879 clinical) (Figure 6-1)—remarking that some of that expense is due to the complexity of the billing system. For example, when a patient comes to the Duke health care system for clinical care and then is also enrolled in a research study, organizing the billing becomes extremely complicated. Indeed, at Duke the time of an estimated 1,200 people is devoted to billing. Additionally, some of the high cost of clinical trials can be attributed to the way they are conducted. A typical industry-funded outcome clinical trial costs on the order of $100–600 million, a figure that could be reduced by simplifying protocols, developing interoperability in data management, and reducing redundancy.

Concluding, Dr. Califf emphasized that the way to establish the envisioned public–private collaboration is through federated informatics: linking existing networks so that clinical studies and trials can be con-

FIGURE 6-1 2005 time-adjusted comparative preapproval capitalized cost estimate per approved new molecule.

a All research and development costs (basic research and preclinical development) prior to initiation of clinical testing.

b Based on a 5-year shift and prior growth rates for the preclinical and clinical periods.

SOURCE: Adapted from Dimasi and Grabowski, 2007. Copyright 2007, John Wiley & Sons Limited. Reproduced with permission.

ducted more effectively, and establishing a data-coordinating center to ensure that patients, physicians, and scientists are using the same data standards and nomenclature. Dr. Califf was asked about the “Wilensky proposal” (Wilensky, 2006), which calls for a distinct comparative effectiveness entity that would set priorities and be directed largely toward postapproval activities, systematic reviews, and observational studies. He responded that he would not want to see different structures built to address comparative effectiveness and postmarket safety because the two functions have so much in common; rather, he would hope that there would be “conceptually one effort, but tailored for different purposes.” Dr. Woodcock expressed her view that for the partnership to work effectively, it would require proper governance and attention to the privacy concerns associated with the variety of entities that could use the system for various purposes. She also echoed the idea that the partnership would pool efforts to meet common needs and thereby be less costly than having