5

Challenges

Numerous challenges must be overcome to develop nationwide digital parcel data that are comprehensive, current, accessible, and in a consistent form that can be used as a framework on which to build more sophisticated and seamless applications. The challenges fall into several broad categories: technical and data, financial, legal, organizational, and political. There are also challenges unique to creating a parcel layer for Native American tribal lands.

Many of the challenges can be overcome with a reasonable amount of thought, organizational skill, and financial incentives. Other challenges would require changes in existing laws, at both the local and the federal levels, and changes in attitudes on the part of stakeholders at all levels of government. Some of the challenges do not individually preclude the development of a national parcel layer, but they all must be solved before the vision of a national parcel layer can be achieved and yield maximum benefits.

5.1

TECHNICAL AND DATA CHALLENGES

Many of the challenges are related to the data themselves or to the technology used to create and maintain them. Because parcel data are dynamic, it is difficult to ensure that they are consistently accurate and up-to-date. Technology available today allows us to approach the development of land parcel data in ways that were inconceivable in 1980 or even a few years ago. Standard geographic information system (GIS) software is now used at all levels of government, high-resolution aerial photographs are available nationwide, vast quantities of data can be stored at relatively low cost, and the Internet has made it much easier to coordinate and communicate on a national level. Therefore, the technical challenges revolve less around the existence of required technology than ensuring that it is applied consistently and to its greatest advantage.

Of course, many localities lack the hardware, software, training, or personnel to automate their parcel data at all. These are, however, not strictly technical obstacles. The technology exists, but organizational and funding problems prevent its adoption in many jurisdictions. These problems are covered in other sections. The points here underscore the reality that even among those that have

the technical capability, some significant obstacles stand in the way of creating consistent, accurate, and timely digitized parcel data on a national basis.

5.1.1

Dynamic Nature of Land Records

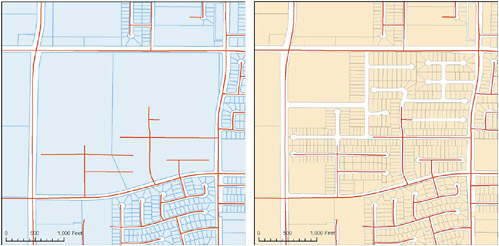

Ideally parcel data reflect the current status of ownership, use, and value of a piece of real estate. Since there are numerous transactions that change any of these factors as well as the actual boundaries, there is often a time lag between the recorded or actual legal transaction and what is reflected in the published digital layer. Parcel maps are constantly changing with new subdivisions, annexations, corrections, and other routine modifications. Figure 5.1 shows how the parcel data for Kern County, California, changed from 2005 to 2006.

Keeping up with the large number of transactions that may occur in any jurisdiction’s parcel database is time consuming and must be handled at the local level because current parcel information is needed for many aspects of local government. The current ownership status is used in permitting, emergency response, land use planning, real estate taxation, and many other local government functions. The number of people and the resources required to keep a parcel data set current vary with the number of new transactions, whether maps and documents are submitted digitally, and the level of automation of the transactions affecting new parcel creation. Sifting through all recorded documents in hard-copy form to find those that affect parcel geometry changes is a daunting task.

How these transactions are implemented varies greatly among local government. In some cases the deed and recorded transaction is updated almost instantaneously, and the real estate record and then the mapping follows. In other jurisdictions, all of the changes are made at once. Any combination of update cycles can be found across the country. Inconsistent maintenance cycles mean that, in many cases, the digital map may not have the most up-to-date attributes available or the mapping may not reflect the current transactions for splits, combination, or new parcels. Furthermore, many jurisdictions outsource this work and obtain a new digital parcel layer in-house only once a year to

FIGURE 5.1 Example of parcel data in Kern County, California, in 2005 and 2006. SOURCE: Map created by First American Flood Data Services. Data provided by Kern County, California.

support a new real estate tax cycle. In other cases, inconsistent maintenance cycles are a result of local tax assessment rules. For example, in many local governments the tax bill reflects a property’s status in the previous year. Transactions that occur during the year are by law not included in the tax rolls until the following year even though ownership or geometry may have changed.

The rate of increase of new parcel creation is about the same as the rate of population increase. Even though the general trend of parcel population density is about 2 people per parcel, in fast-growing areas, highly urbanized areas, or in rural areas, these numbers vary (Stage and von Meyer, 2006b). New parcels are reformed from existing parcels through splits and combinations as well as created in new plats and subdivisions. This often requires sorting through many documents to identify and interpret the information. The motivation for a local government to maintain these transactions is to support the local business processes such as real estate taxation, permitting, and law enforcement and public safety programs that require current and accurate information.

5.1.2

External Distribution of Parcel Data

Most local parcel data programs maintain a production and a publication version of their parcel data. The publication version is one that is made publicly available. The production version may contain much more detailed data, such as detailed survey work. In the most sophisticated programs the internal production system is maintained in real time as property transactions are recorded. Therefore, it is possible that applications within a county may be based on current data, but the community may update its external offerings only on a monthly, quarterly, or even annual basis. Even if the data in the local digital parcel layer are as accurate and current as possible, any data stored separately at a state or national level can easily get out of sync. It is technically possible to create a system where the data at a national level exactly match the data available locally, but the cost and administrative burden must be balanced against the need for real-time currency.

5.1.3

Quality of Data in Existing Digital Parcel Maps

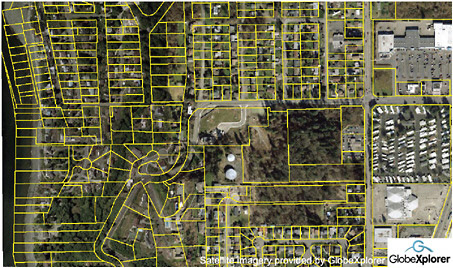

Incomplete, out-of-date, and inaccurate data often exist in digital parcel maps. At the local level, parcel maps primarily support local property taxation and are usually adequate for that purpose. However, their underlying base maps can be many years old and they are often georeferenced incorrectly, do not align properly with high-resolution orthophotography, and may be internally inconsistent due to the original sources and methods used to create the data. Poor quality control, especially in terms of geographic accuracy, is understandable because of the cost of producing highly accurate data. Figure 5.2 shows how parcel data from King County, Washington, does not line up well with aerial imagery because of issues encountered during the conversion of hard-copy maps to digital format. Other errors can occur because the existing hard-copy maps may have been developed from “assumed” reference systems, such as presuming that Public Land Survey System sections are square or that individual parcel boundaries follow visual evidence such as fence lines or water edges.

There are many different approaches to the creation of parcel polygons that vary substantially in cost. Very few communities can afford the cost of compiling parcel data directly from the legal description on a deed because of the labor-intensive process of interpreting and resolving discrepancies in legal descriptions found in many deeds. Often the more exacting method using coordinate geometry and topology rules is employed for a subset of parcels such as those that have been recently surveyed and compiled on a plat of survey where the distances and bearings can be relied upon as being consistent and accurately presented. In most other cases the parcel fabric is created by digitizing existing hard-copy sources. In most jurisdictions, it is not legally required that the parcel legal descriptions in deeds be compiled and verified by a land surveyor. This often leads to

FIGURE 5.2 King County, Washington. The parcel boundaries line up well with the streets at the right side of the image but are increasingly misaligned toward the ocean. According to the county, a lack of control points on the original Mylar-based parcel records caused the shift when they were converted to vector parcel boundaries. SOURCE: Compiled by First American Flood Data Services using data from King County Washington Department of Natural Resources and Parks, Geographic Information Systems Center (parcel boundaries) and GlobeXplorer (aerial photo). Used with permission.

legal descriptions that are unclear, are nearly impossible to locate, and contain geometry errors. This is a bigger problem than the technical issue, since most GISs contain the tools needed to perform the coordinate geometry computations. It may take field work or legal interpretations to resolve inconsistencies in legal descriptions in deeds.

As information systems have become an integral part of our lives, many individuals are impacted by erroneous information about their credit ratings and other important personal information. Inaccurate or incomplete information about land records can also have a serious impact on individuals and their property. For example, the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC) has filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission regarding what it believes is the inappropriate role of Zillow.com in providing estimates of property values. In an article in Real Estate Technology News (2006), David Berenbaum, executive vice president of NCRC, stated:

The crux of our complaint is that Zillow’s over and under appraisals negatively impact on consumers’ real estate and financial transactions, and injures entire communities…. While the focus of the attached complaint is upon all communities regardless of income, the fair housing complaint will argue that Zillow perpetuates the undervaluation of low-moderate income communities in violation of the Federal Fair Housing Act.

The complaint specifically charges that property owners can be harmed when information about their property is not being directly controlled by public officials who are accountable to taxpayers and voters.

The following comments reveal the importance of accurate parcel data:

Cadastral mapping has taken on a new role in personal safety with the age of E911 [emergency 911] and homeland security. Inaccurate parcel data now can cause slow or non response to emergency situations that could cause harm. (Comment from web forum: William Cozzens, Land Information System Analyst, Waukesha County)

Assessment records are good, but realtors have repeatedly misinformed taxpayers as to school boundary lines which causes the taxpayer to buy a home that is not in the district they wanted … and then when trying to enroll their child, they find out the property is not in the district. Even one case where someone ran for school board, won, and then found out that they were not in that district. Uniform parcel information might help realtors even though the info is there for them to discover. (Comment from web forum: Mapping Supervisor, County Assessor’s Office)

5.1.4

Reconciling Data at Administrative Boundaries

Local parcel programs are operated as an internal business function. In many states there are no standards or requirements for these parcel data to be combined with those of adjacent counties. In fact, there are many examples of municipal governments maintaining data on parcels within their jurisdiction without any coordination with the county of which they are a part.

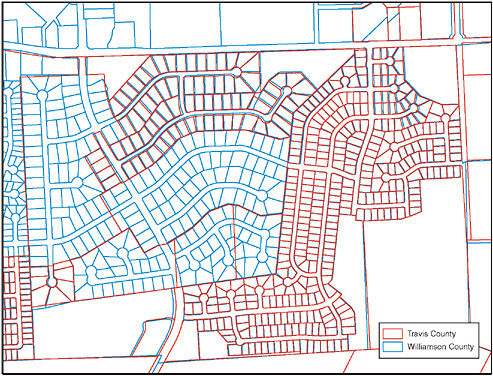

The independent nature of this production process leads to significant problems when reconciling data at municipal, county, and state boundaries. Each local parcel layer inserted into a national “fabric” must have its external boundaries reconciled with those of adjoining states, counties, and if appropriate, cities and towns. Figure 5.3 is an example of where the parcel data across two counties overlap. There have been a few successful efforts to merge parcel data across states or among counties at a regional level. Good examples are the seven-county MetroGIS region in the Minneapolis-Saint Paul area and the three-county Portland, Oregon, region. The only solution to this issue involves a comprehensive approach to accurately creating and maintaining administrative areas and establishing a clear understanding of data stewardship responsibilities. If there is a clear understanding of the stewardship responsibilities across jurisdictional boundaries and agreement on the location of those boundaries, parcel data can be seamlessly assembled.

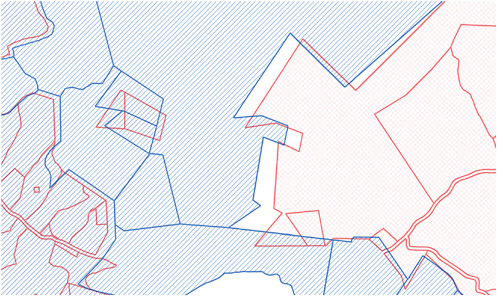

A related issue is reconciling federal land parcels with local data. Information about parcels on federally managed land is usually not recorded with or stored in local government systems. For example, tribal trust lands and U.S. Forest Service (USFS) use areas are not recorded with the counties in which they exist. The western parts of Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties in Florida all have National Forest areas, but none of these counties maintain parcel features for those areas. Even if data on federally managed parcels are available and accurate (see Section 5.4.1), they must be reprojected and the boundaries reconciled with local data. This reconciliation process may reveal encroachments that have to be resolved politically or through the courts. This same situation can also occur with regard to state-owned lands. Figure 5.4 illustrates this issue.

This situation can be extremely problematic in areas where the federal-local jurisdiction is a checkerboard with the maximum possible edges to adjust and edge-match. With Indian trust lands, this can go down to the grain of individual parcels, since as mentioned in Chapter 4 there can be a large number of non-Indian-owned land parcels within a reservation. Since the development of nationally integrated land parcel data would involve reconciling parcel boundaries among different land managers, this will undoubtedly expose and ultimately force the resolution of issues with jurisdictional boundaries.

Much as with administrative boundaries, for full reconciliation and exact edge matching between areas with different maintenance agencies, a stewardship boundary needs to be agreed upon. By setting and agreeing to a common boundary, parcels on either side can be matched to the common boundary, reducing edge-matching issues. The committee recognizes that this is not

FIGURE 5.3 Parcel data maps from Travis County (red lines) and Williamson County (blue lines) in Texas, showing overlap in the parcel maps. SOURCE: Map created by First American Flood Data Services using data from Capitol Area Council of Governments (http://www.capcog.org).

an insignificant task and it will require dedicated effort and time on the part of all data stewards to reach resolution of the edge-matching issues. Eventually a single data steward will be identified for all surface ownership to create seamless parcels across stewardship areas.

5.1.5

Multiple Coordinate Systems

Parcel data are maintained in multiple geographic coordinate systems. Existing parcel data have been created using a variety of map projections and horizontal datums. In fact, some counties, such as Ada County, Idaho, or states such as Minnesota and Wisconsin have built custom coordinate systems specific to their geographic areas. Sometimes this important information is well documented and sometimes it is not. While most modern GIS software is able to adjust for any of these assumptions, a parcel aggregator must have complete and accurate metadata in order to fit any local parcel data into a continuous nationwide fabric.

FIGURE 5.4 Cherokee County, North Carolina, tax maps (red) with USFS tracts (blue) on top. This data set was assembled from county parcel data downloaded from the county file transfer protocol site and adding USFS tracts shape files. This figure illustrates that when agencies with parcel data management responsibilities in the same area work independently, mismatches between parcel boundaries can develop.

5.1.6

Definition of Street Addresses

There are inherent problems with street addresses. An accurate site address is a key attribute of any set of digital parcel data and a critical part of any emergency 911 or package delivery system. In the case of a standard residential parcel containing one single-family home, the definition is straightforward. However, other parcels may contain multiple buildings, each with different occupants, or buildings with multiple occupants. Different users of the parcel data may have different interpretations of an “address,” depending on whether they are looking at the parcel as a whole or whether they care about each structure, each dwelling unit, or even each utility connection. Address attributes currently found on many counties’ parcel databases are often inaccurate. Furthermore, an address can be formatted and stored many ways (e.g., “120 NO MAIN,” “120 NORTH MAIN STREET,” “120 N MAIN ST”). In many jurisdictions, vacant or uninhabited parcels are not assigned an address.

As noted previously, the Urban and Regional Information Systems Association (URISA), sponsored by the Census Bureau, has worked with the National Emergency Numbers Association and the U.S. Postal Service to develop a proposed FGDC address standard. Parcel data standards and any developments in terms of standardized street addresses need to be synchronized.

5.1.7

Inconsistent Practices for Complex Parcels

Parcel maintenance programs often employ inconsistent practices when handling complex parcels. There is no standard way to represent more complex “parcels” such as condominiums or

other common interest areas, especially when the buildings have multiple units (i.e., the parcels are vertically “stacked” or include individual building footprints in addition to the surrounding parent parcels). Figure 5.5 shows an example of this type of parcel.

5.1.8

Poor Utilization of Consistent Standards for Data Quality

Although the Federal Geographic Data Committee (FGDC) Subcommittee for Cadastral Data has developed and adopted a standard for land parcel data, it is not widely used. The absence of consistent standards for data content and data quality can lead to serious problems. Any sound data management program must adhere to accepted data management practices to deal with locational attributes, period of ownership, consistent parcel identification numbers, retired parcels, missing parcels, related rights and easements, and bad survey data. Fortunately the FGDC standard and related best practices are gaining in acceptance, and states such as Florida, North Carolina, and Arkansas have adopted the standard as a statewide requirement. Also, the data content standard has been simplified so that the content reflects the data necessary to support a specific business need. With the adoption of the business-based “core data,” there has been an increase in use of the standard.

Another set of relevant standards is developed through the efforts of the International Association of Assessing Officers (IAAO). The IAAO issues voluntary standards that guide professionals in the ad valorem assessment business. The IAAO has a strong presence in the 50 states at the local assessment professional level and also with state property tax departments. Of particular note are

FIGURE 5.5 Example of parcels with multiple units in each parcel. Each dot represents a separate housing unit. SOURCE: Delaware County Auditor’s Office.

the Standard on Manual Cadastral Maps and Parcel Identifiers and the Standard on Digital Cadastral Maps and Parcel Identifiers.1 These standards are available to IAAO members online and to the public for purchase.

5.1.9

Existing Legacy Parcel Systems

The installed base of existing legacy systems for parcel data production is substantial. Many of these legacy systems are in major metropolitan areas that were the leaders in developing computer-based parcel management systems. A few of these are in heavily populated areas such as Los Angeles that are struggling with the need to migrate their original systems to a modern information infrastructure. Legacy systems have both data quality and political-financial issues. While these older systems may still serve local needs, the data may not adhere to modern standards and may have been compiled from original resources such as paper tax maps that were not as accurate as current resources. One might not expect that these counties, some of which are quite large, would require outside aid to contribute to a national parcel data system, but their substantial existing investment may make them reluctant to modernize. Similarly, they may feel it necessary to charge for their parcel data in order to recoup the costs of their investments. The Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission is one example of an area that was a very early adopter and developer of a multipurpose cadastre for the counties in the region. In fact, this was one of the systems cited extensively in earlier National Research Council (NRC) reports as a stellar system. With a relatively large data holding based on the methodology and processes available in the early 1980s (including the North American Datum of 1927 reference system), moving to more modern systems and approaches regionwide was nearly prohibitive. Over time, individual counties in the region, such as Waukesha County, have undertaken migration and modernization, but at much cost and effort. The committee believes that while the need to migrate the GIS environment is a tangible issue in some communities, it is not unique to parcel data systems. Many local government budgets are strained by the constant need to modernize their information hardware and software.

5.1.10

Secure, Reliable Data Storage and Backup

Secure, reliable data storage will be a critical need. Any system that stores and serves data at an individual property level, particularly one that is federally sponsored, will have to meet strict security standards. However, a model that contemplates a national parcel data set of more than 144 million parcels as a federation of dispersed systems, as opposed to a single central repository, faces unique security and reliability challenges. The data must be protected from unauthorized modification and must not be stored in a way that creates the possibility of a single point of failure. For example, data physically stored only at a local level may not be accessible, or may be lost forever, in aftermath of a natural disaster, just when they are needed most. Therefore, backup of data at a physically separate location is important.

5.2

FINANCIAL CHALLENGES

Developing a funding model for nationally integrated land parcel data must take into consideration three different elements: (1) the cost to convert all parcel data that has not yet been digitized to digital format; (2) the cost to maintain the parcel data (i.e., to update them when new parcels are formed or information has changed); and (3) the costs to make the data consistent and accessible nationally. Each of these is discussed separately below.

|

1 |

For IAAO standards, see http://www.iaao.org/documents/index.cfm?Category=23 [accessed May 25, 2007]. |

The FGDC Subcommittee for Cadastral Data has estimated the costs for item 1, which are the costs to complete initial digital data coverage (Box 5.1) (Stage and von Meyer, 2007). The subcommittee estimated that it would require about $294.6 million in one-time costs and $84.7 million in recurring costs to complete the coverage of digital parcel data for the United States. This covers the costs of the initial digital conversion or reformatting required for getting to a published format and establishing the necessary institutional framework. The recurring costs include items that will have to be updated periodically (such as imagery as a backdrop) or the costs to fund ongoing activities (such as training or extracting a subset of the data to make an annual published view). The numbers of parcels yet to be converted is based on state surveys done in 2003 and 2005 and updated in the 2007 wildland fire inventory process.

The FGDC subcommittee estimates that there are about 152 million parcels that cover the United States: 8 million of these represent public lands and the remaining 144 million cover private land ownership. The subcommittee assumes that all public land parcels should be converted into a digital format as part of the stewardship responsibilities of the local, state, or federal agency that controls the property. It is estimated that about 68 percent of the 144 million private parcels are already in digital format. The remaining parcels are concentrated in approximately 2,200 largely rural counties, which are unlikely to have the resources or know-how to complete the parcel conversion. The subcommittee assumed a conservative estimate of the cost of creating a GIS representation

|

BOX 5.1 Estimated Cost for Producing Parcel Data for the Nation The FGDC Subcommittee for Cadastral Data estimates that it would require $294.6 million in initial one-time costs, with recurring costs of $84.7 million per year to complete a national set of land parcel data. The one-time cost includes the following:

The recurring cost of $84.7 million includes the following:

This estimate is based on a recent inventory of the status of parcel data in all 50 states. The figures assume that each county will be responsible for the conversion and maintenance of parcel data in its jurisdiction and that all counties and states with existing data will need resources for the publication of the county data in a standard format and the integration of these data into uniform statewide parcel data coverage. SOURCE: Adapted from Stage and von Meyer, 2007. |

of the geometry of the parcels as $2.00 per parcel for point-level representation and $5.20 per parcel for polygon representation, based on conversion cost averages nationwide from samples across the country. As independent verification of these estimates, the State of Tennessee estimates that it cost $9 million to convert 2.7 million parcels (about $3.70 per parcel) (D. Pedersen, State of Tennessee, e-mail to D. Cowen, May 14, 2007) and the State of Montana spent about $4 million to convert 1 million parcels (Stevens, 2002).

The challenge in funding the completion of digital parcel data coverage for a national parcel system is not primarily one of finding the money. For example, note that 88 percent of the recurring costs listed in Box 5.1 are for acquiring imagery on a three-year cycle. However, there are federal programs within the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Geological Survey that acquire or cost-share imagery. The Imagery for the Nation program proposed by the National States Geographic Information Council (NSGIC) would institutionalize imagery acquisition for the nation on the same three-year cycle. Therefore, recurring costs of imagery production in the estimates in Box 5.1 could be substantially lower. Furthermore, parcel data are so important to carrying on the day-to-day business of state and local governments, that many ways have been found to fund parcel data development. The State of Arkansas Cadastral Spatial Data Infrastructure Business Plan provides an example of how it proposes to fund parcel data (Arkansas Assessment Coordination Department and Arkansas Geographic Information Office, 2006):

County Assessor hardware, software and training is funded by the Assessment Coordination Department. Additional training, technical support, supporting data, and the publication of web accessible cadastral data are funded by the Arkansas Geographic Information Office. The state is researching the feasibility of additional funding from the state to counties for more personnel. In the meantime both state agencies and the individual counties are opportunistic about pursuing additional outside funding resources and taking advantage of those when feasible. The statewide consistency with the data, technical, and business processes make Arkansas an outstanding candidate for completing a statewide cadastral database. This situation makes for a low risk, high return opportunity for federal, non-profit and private funding investments to accelerate and complete cadastral data throughout Arkansas.

Perhaps more importantly, it must be emphasized that the committee views the establishment of parcel programs by a local government to be at least revenue neutral. For example, a county assessor in Florida was able to find 8,000 acres that were not on the tax roll as a result of parcel conversion (Stage and von Meyer, 2006a).

However, much of the current funding to collect and aggregate existing digital parcel data is uncoordinated and duplicative. In fact, enormous amounts are already being spent on creating and maintaining digital parcel data and there are many examples where data on the same parcels are being maintained by a city, the county, and also private utilities and title and insurance companies. Unfortunately, some of these duplicative programs exist as a result of technical or institutional barriers that prevent collaboration. States, federal agencies, and numerous private sector users pay over and over to acquire and aggregate the same parcel data for their own purposes.

It appears that there are many potential sources and methods for funding completion of digital parcel data coverage. The challenge will be better coordinating existing opportunities, developing effective partnerships, and providing new funding where needed to complete the digital coverage.

The second cost element is maintenance of the parcel data once they have been converted to digital form. This includes the costs of keeping the parcel data current, such as adding new parcels or updating related information with new owners and new values. Maintenance of parcel data is often a modernization of the tax map operation that is required by most state departments of revenue and therefore is considered a cost of doing business. As noted earlier, having current parcel data is essential to many functions of local, state, federal, and tribal agencies. What portion of a government’s

operations is just for parcel data maintenance costs, or what factors contribute to these costs, are difficult to estimate accurately on a nationwide basis. For this reason, the FGDC Subcommittee for Cadastral Data does not provide an estimate of these costs. This committee did a preliminary analysis of what maintenance costs might be based on several different methods. However, like the FGDC subcommittee, it was found that the cost of maintenance depends on so many factors (size of the county, how quickly the county is growing, who is maintaining the data) that a reasonable estimate could not be developed. Nevertheless, in terms of a national system for land parcel data, the costs of maintaining the data will in most cases be borne by the data stewards as a cost of doing business. The challenge will be in supporting those local government entities that cannot afford to maintain or publish the updated attributes needed for a national system in digital format. In some cases, states have already stepped in to cover this function for counties that are unable to do so.

Finally, there are costs for creating nationally integrated data that go above and beyond the development of the original parcel data costs. For example, there are costs associated with edge-matching parcel boundaries along county and state borders and reconciling public and private lands. Some of this work has already been done as regional groups or states have been compiling parcel data sets for their areas. Private industry has also had to address this issue as it has begun building parcel data systems. Another element of the cost would be to establish an infrastructure for accessing the most current data from the parcel producers and making them available in a seamless format. Systems with these capabilities exist for other purposes, so the major challenge is to find a source of funding. Finally, costs would be incurred to support the national coordination function. All of these elements of a national land parcel data system would most likely have to come from new funding.

Therefore, financial challenges must be addressed for the production of the initial parcel data coverage, the integration to make the data nationally consistent, and the infrastructure to make the data accessible. There is a concern among parcel data producers as to who would bear these costs, as illustrated by the comment below:

Managing parcels for a county of 600,000 people is already difficult. I do not believe that the overhead of complying with a national mandate will provide, at the producer level, any benefits. Therefore I see the potential for increased costs and overhead, as a potential liability. (Comment from web forum: Stephen Marsh, Director, GIS Department, Jackson County, Missouri)

The big question is how to assemble the collective interest in parcel data to financially support a national land parcel data system that covers every part of the country. Ideally, all stakeholders would contribute to the program. A representative from Zillow told the committee at the Land Parcel Data Summit that it encounters major problems with acquiring consistent data from local governments at a consistent price. Zillow is willing to help support the production of parcel data but would like to see a reasonable and consistent price for it. Although there seem to be potential sources of funding, the committee recognizes that coordinating these opportunities and partnerships and developing an equitable funding model will be a challenge.

5.3

LEGAL CHALLENGES

5.3.1

Data Sharing Restrictions

Even though data about land ownership and value are considered to be public information, a number of barriers inhibit the exchange of parcel-related data. Since land parcel data are the basis of many legal and economic decisions within a community, they are also likely to have restrictive policies regarding licensing and distribution. The importance of these distribution issues was covered at length in the NRC report Licensing Geographic Data and Services (NRC, 2004a). It is

important to understand the concept of ownership and restrictions on the use of geographic data as they pertain to land parcels. These issues also directly impact the financial arrangements that may impede the type of federal and local government partnerships that would be necessary to support a successful program.

Copyright and Public Domain

While ownership of geographic data is inherently an ambiguous concept it is extremely important in terms of copyright and Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. The NRC Licensing report provides a clear statement on copyright (NRC, 2004a, p. 107):

Although geographic data equivalent to facts will not be protected by copyright, compilations of geographic data such as databases and datasets, as well as maps and other geographic works that incorporate creative expression, may have copyright protection.

From this definition, surveyor’s coordinates, parcel corners, and unprocessed aerial photography fall into the category of raw data. In a legal context, courts have decided that such native data are facts and cannot be copyrighted and may be subject to public disclosure under most FOIA requests. However, fully attributed parcel data may be considered information rather than data and may be protected by a copyright.

The report also provides a useful definition of public domain (NRC, 2004a, p. 277):

Information that is not protected by patent, copyright, or any other legal right, and is accessible to the public without contractual restrictions on redistribution or use.

There is a major difference between the way the federal government and other levels of government embrace the concept of public domain. Federal policy is based on the premise that data derive their value from use, and the government wishes to actively foster a robust market of secondary and tertiary users. Therefore, the federal model as specified by Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circular A-130 can be summarized as (1) no copyrights of government data; (2) fees must be limited to the cost of dissemination; and (3) no restrictions on reuse of the data. The federal philosophy regarding sharing public data is encapsulated in the following statement (OMB, 1996):

The free flow of information between the government and the public is essential to a democratic society. It is also essential that the government minimize the Federal paperwork burden on the public, minimize the cost of its information activities, and maximize the usefulness of government information.

This federal government public domain policy has profound impacts on the relationship between the federal and local governments. For example, when the Census Bureau acquires a file of street centerlines from a local government to use for its Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing (TIGER) modernization program it must place those data in the public domain. In contrast, many communities do not want to lose potential revenue and therefore have not agreed to provide the Census Bureau any data that they normally license to third parties.

Even though under OMB Circular A-130 the majority of federal government geospatial data are considered to be in the public domain there are several important exceptions, such as the Census Bureau’s Master Address File (MAF). As described in Chapter 4, the MAF/TIGER Accuracy Improvement Project will result in a major improvement in the positional accuracy of the TIGER line files and the location of residential dwelling units. In addition to the extensive work that is being conducted by a private contractor the program will also utilize Census employees armed with

500,000 hand-held global positioning system units to support the Field Data Collection Automation program. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has raised several issues about the reliability of this program and the lack of a successful dress rehearsal based on the use of the hand-held computers (GAO, 2006b). The information in this updated MAF will not be released to the public. Historically, the conduct of the decennial Census is tightly controlled by Congress. The procedures that the Census Bureau must follow are designed to ensure the highest level of confidentiality for individual responses. Many communities have requested some of the information resources that the bureau uses to conduct the decennial Census. In 1982 one of these requests led to Supreme Court decision in Baldridge v. Shapiro (455 U.S. 345, 1982). In that case the Supreme Court held: “The master address list sought by Essex County is part of the raw census data intended by Congress to be protected under the Act [Title 13].” In that decision the Court endorsed the Census Bureau’s reading of Title 13. It wrote: “The unambiguous language of the confidentiality provisions, as well as the legislative history of the Act, however, indicates that Congress plainly contemplated that raw data reported by or on behalf of individuals was to be held confidential and not available for disclosure.” Consequently, the bureau has interpreted the Supreme Court decision to mean that any data collected by bureau staff to assist with the Census itself is confidential. Furthermore, as described in congressional commentary, Congress does not want to make the MAF public for the following reasons (Sawyer, 1994):

The subcommittee is well aware of, and sensitive to, concerns about personal privacy. It’s probably true that most people do not view an address, without related names, as private information. Frankly, address information is widely available in today’s society from public and private sources. However, for two reasons, the legislation allows for only limited access to this most benign piece of census information.

The first reason is that it may be difficult to communicate clearly to the American public that the information in question does not contain names or any other identifying information besides the physical location of a housing unit. Given the special trust that must exist between the Census Bureau and much of the American public, we did not want to jeopardize the Bureau’s ability to garner cooperation in future censuses.

The second reason for limiting access is that the Bureau’s definition of a housing unit is necessarily broad and may include information not generally known. For example, that definition includes illegally occupied garages, offices, basement apartments, and other structures not normally inhabited. But while the effort to include every structure where a person lives is essential for an accurate count, the Bureau might inadvertently have information on its address lists that indicates the existence of a structure not properly zoned for residential dwelling. If the census address information were misused, an individual might face some adverse result.

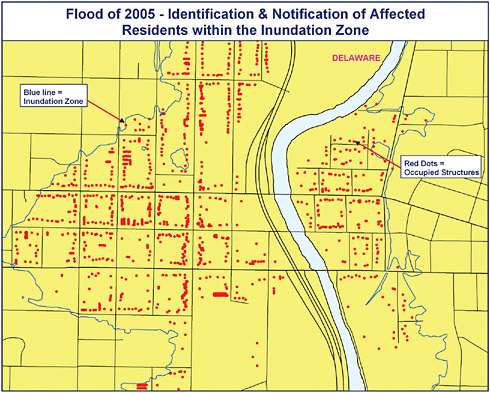

It should be noted that there are alternative ways to capture point-level residential features. For example, communities with good parcel production programs could provide the Census Bureau with a highly accurate and current set of street addresses and associated coordinate points. In many areas, addresses are assigned to parcels or to structures as part of a synchronized work flow. They become the official part of the attribute information stored with a parcel. Often the specific location is assigned to a structure within the parcel. These address files typically become the basis for updates to the emergency 911 dispatch system that enables emergency vehicles to respond to events. This approach was highlighted on a National Public Radio feature on this topic (Charles, 2006). Figure 5.6 shows an example of point-level address data collected by Delaware County, Ohio. A second source of point-level residential features exists in the private sector. For example, Tele Atlas has a file of more than 40 million address points and is working to expand it to 100 million (Tele Atlas, 2007). This file is being created from extensive field work and high-resolution imagery.

Conversely, the Census Bureau has determined that the TIGER street centerline data are only used as a tool for summarizing and reporting those data; therefore, they fall outside Title 13. While

FIGURE 5.6 Point-level addresses in Delaware County, Ohio, in relationship to flood inundation zone. SOURCE: Delaware County Auditor’s Office.

the committee appreciates the bureau’s need to comply with the directives of Congress and the Supreme Court it believes that the address points are actually just an enhancement to the TIGER line file based address system. It is important to note that since the 1970 decennial Census the Census Bureau has always distributed GIS files with street names and address ranges that facilitate automated address matching. In fact, it provides public domain software (Landview) that enables a user to locate an address and associate census information and other themes to that location. It could be argued that the improved point-level locations for addresses are simply an enhancement of these address matching capabilities and have nothing to do with confidential information about the residents of the dwelling units. This issue is of relevance since these expensive and valuable point-level features could provide an excellent tool for creating a national parcel database.

There are also restrictions on address information relating to the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). These restrictions were upheld by the U.S. Court of Appeals (Forest Guardians v. U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency, 410 F.3d 1214 [U.S. App. 2005], June 14, 2005, Filed) in a case where the nonprofit organization Forest Guardians brought an action under the Freedom of Information Act, 5 U.S.C. § 552, seeking to compel the Federal Emergency Management Agency to release GIS files that identify the location of structures insured under the NFIP. The court ruled

that the GIS files were exempt from FOIA because they would reveal policy holders’ names and addresses, which would be an invasion of their privacy.

Local Government Licensing Issues

Outside of the federal government there is no standard set of practices or rules regarding access or distribution of geospatial data. At one end of the spectrum, a local government may establish very strict licensing agreements that control access to data assets and restrict the use and redistribution of the data. These arrangements are often related to the generation of revenue but can also exist to promote participation in consortia. Others use licensing as a way to control access to the data, as illustrated by the following comment.

Because more than 50% of our private parcels (9.2% of our county is private) are seasonal in nature, we have a concern that certain elements might target those homes. Therefore, even though the information is public, we do not dispense the information on the internet. Everyone who gets electronic data must sign a license agreement. (Comment from web forum: Loretta Bloomquist, Cadastral Mapper, Cook County, Minnesota [retired], February 2006)

While these arrangements are most often found in local governments they also exist at regional levels such as the Metro GIS in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area and the Portland, Oregon, region. They even exist on a statewide basis in Tennessee. In Minnesota, where the state is one of the largest landowners, the state Department of Natural Resources (DNR) would like to share data with local counties. This has proven to be nearly impossible in the central region of the state. Each county has a unique license agreement for its parcel data that it strenuously enforces. DNR land managers have given up the effort, because of the time it would take its legal department to review and approve those licenses.

At the other end of the spectrum, several counties, including Delaware County, Ohio, and the entire State of Montana, provide a simple web interface for free download of a published version of parcel data without any fees or licensing agreement. The NRC Licensing report observed that over the past decade many state and local governments have experimented with fee-based programs with restrictions on the use and redistribution of data, and found that most of these fee-based programs (1) cannot recover a significant fraction of government data budgets, (2) seldom cover operating expenses, and (3) act as a drag on private sector investments that would otherwise add to the tax base and grow the economy (NRC, 2004a, p. 97).

There have been a number of important decisions relating to the legal and financial barriers that limit data sharing. Two cases have gained considerable national attention and relate directly to this study.

Greenwich Connecticut. In 2005 the Connecticut Supreme Court decided that the City of Greenwich had to release GIS data to a private entrepreneur. The court rejected the city’s claim that trade secret exemptions could apply to the electronic GIS maps. It decided that all information contained in the maps is available from town departments; therefore it is not secret. The court also rejected the claims that release of the information could pose a risk to public safety.

The case is significant on the national level because of the interest of members of the press. The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press Society of Environmental Journalists Investigative Reporters and Editors, Inc. filed an amicus curiae, or “friend-of-the-court” brief in the case that drew the following argument (Klau, 2004):

Publicly funded computerized Geographic Information System (GIS) records, and the maps generated from GIS systems data, have become a basic tool for government study and decision-making in fields such as environmental policy, public safety, and health. The public also requires

access to GIS records and maps relied upon by government officials in order to conduct its own study and to monitor, criticize, and, as warranted, challenge decisions based upon that data. Journalists represented by amici play a key watchdog role in this process. They must be able to access original computerized GIS data and maps used by official decision-makers and disseminate them to the public. Thus, amici have a vital interest in ensuring that the government places no improper restrictions on the public’s right to obtain those records.

California. In March 2006 the Los Angeles County assessor made a major change in policy regarding the distribution of its parcel data. The county reacted to the California state attorney general’s opinion that “parcel boundary maps maintained in electronic format by a governmental entity are subject to public inspections and copying under provisions of the Public Records Act and therefore must be provided for the cost of duplication in accordance with the parameters set forth in the California Public Records Act” (Auerbach and Wolfe, 2006). As a result, the price to access Los Angeles County parcel data changed overnight from $100,000 to the cost of reproduction. However, 13 other counties, including Santa Clara County, continued to charge high fees for their parcel databases. A suit was filed against Santa Clara County by the California First Amendment Coalition (CFAC), claiming that these are public data that should be freely available. In May 2007, the California Superior Court for Santa Clara County ruled in favor of CFAC that the county must release its data at the cost of reproduction.2

In some cases local governments operate under Memoranda of Understanding that allow vested business operations such as energy management, wildfire response, or hurricane response to have full access to parcel data when needed for specific situations. These most often limit subsequent data distribution, but they do open the door for the use of parcel data in these specific situations. However, as seen from the discussion above, licensing and restrictions on distribution of parcel data constitute an issue that must be addressed in order to develop national land parcel data.

5.3.2

Liability for Incorrect Data

There is always a risk that a user may have an unrealistic expectation about the accuracy of parcel data and misuse them. For example, if an emergency responder is directed to the wrong address, a police-warranted search breaks down the wrong door, property is incorrectly, inaccurately, or improperly assessed or taxed, or data in hand are used for an analysis rather than getting newer and more current data and improper decisions are made, the aggregator(s) and original creators of the data could be subject to official complaints or even lawsuits. This fear of litigation or concern about downstream users not having the most current available information may make some local governments reluctant to participate in a national initiative. Liability issues may raise concerns regarding incorrect parcel data.

These issues were explored in detail in the recent NRC report Licensing Geographic Data and Services (NRC, 2004a). This study found that the use of a license with a disclaiming warranty helps both data acquirers and providers allocate risk and that licensing has become a common mechanism as a result of this increasing concern over potential liability. While concerns over liability issues may be considered a serious challenge to a national parcel data program, the aforementioned NRC report found that “well-designed disclaimers have little or no impact on consumers’ ability to extract, use, or manipulate data” (NRC, 2004a, p. 201). As an example, the Delaware County, Ohio, GIS program simply includes the following statement on its website and requires a user to agree to these restrictions as part of a registration process.

|

2 |

See http://www.opendataconsortium.org/ or http://www.cfac.org/content/index.php/cfac-news/press_release/ [accessed May 29, 2007]. |

DISCLAIMER: The material on this site is made available as a public service. Maps and data are to be used for reference purposes only. Delaware County and its agents, consultants, contractors, or employees provide this data and information “AS IS” without warranty of any kind, implied or express, as to the information being accurate or complete. Map information is believed to be accurate but accuracy is not guaranteed. With knowledge of the foregoing, each visitor to this website agrees to waive, release and indemnify the Delaware County, its agents, consultants, contractors or employees from any and all claims, actions, or causes of action for damages or injury to persons or property arising from the use or inability to use Delaware County GIS data. SOURCE: http://www.dalisproject.org/(S(5afpu145mizkmlvujxoyiaff))/pages/downloadreg.aspx [accessed June 14, 2007].

5.4

ORGANIZATIONAL CHALLENGES

There are a set of issues regarding how a national land parcel program would be managed and coordinated. There is no question that a standardized integrated national system for land parcel data would be complex and its success would depend on intergovernmental cooperation and adherence to standards. There is certainly a risk that the system would attempt to meet too many objectives. As in any information system the risk of failure would increase with the scope of the project.

5.4.1

Federal Agency Coordination

As described in Chapter 4, there are numerous federal programs related to land parcel data, but coordinating across the various agencies to create a consistent database has been difficult. GAO found that more than 30 federal agencies control hundreds of thousands of real property assets worldwide, including facilities and land, worth hundreds of billions of dollars (GAO, 2003a). Even though the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has been designated the steward for federal land ownership it is not the single focal point for those functions. For example, the General Services Administration (GSA) manages information about real estate, buildings, and facilities, and a variety of land agencies (USFS, National Park Service, BLM) manage information about surface and subsurface land depending on the mission of the agency. A complete list of federal properties does not exist, let alone with accurate geospatial information. This poses technical challenges to the creation of national land parcel data. The federal government’s poor management of its real property assets is one of the high-risk activities of the government, as identified by GAO (2005). In testimony before the House Interior Appropriations Subcommittee on March 2, 2005, then-Interior Secretary Gale A. Norton said, “The Department currently uses 26 different financial management systems and over 100 different property systems. Employees must enter procurement transactions multiple times in different systems so that the data are captured in real property inventories, financial systems, and acquisition systems. This fractured approach is both costly and burdensome to manage” (Norton, 2005).

Congress has repeatedly called for inventories of federal lands, but these have often been single-purpose, single-agency requirements. For example, Section 1711 of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (43 U.S.C. 1711) requires that the Secretary of the Interior prepare and maintain a continuing inventory of public lands, including their boundaries. A similar inventory of forest and agricultural lands by the Secretary of Agriculture has also been stipulated by several acts. The Agricultural Foreign Investment Disclosure Act requires all foreign owners of any U.S. land used for agricultural, forestry, or timber production to report their holdings to the Secretary of Agriculture so that USDA can provide an annual report. Other provisions of law have required the federal government to inventory land for various purposes, such as for (1) an Abandoned Mine Land Inventory, (2) a National Wetlands Inventory, (3) siting a refinery, (4) identifying facilities and properties that can be used to provide emergency housing in case of disasters, or (5) assess-

ing the value of lands for management of the recovery of any species included in a list published under Section 4(c) of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 and for addition to the National Wildlife Refuge System.

The Bush Administration is attempting to address this problem. Executive Order 13327, issued February 4, 2004, calls for the creation of “a single, comprehensive, and descriptive database of all real property under the custody and control of all executive branch agencies.” However, there are shortcomings with the executive order and its implementation. First, public lands are exempt (Federal Real Property Asset Management, 69 Fed. Reg. 5897, 5900 [February 6, 2004]):

Sec. 7. Public Lands. In order to ensure that Federally owned lands, other than the real property covered by this order, are managed in the most effective and economic manner, the Departments of Agriculture and the Interior shall take such steps as are appropriate to improve their management of public lands and National Forest System lands and shall develop appropriate legislative proposals necessary to facilitate that result.

Second, the inventory being developed by GSA in response to this executive order does not have a cadastral, mapping, or geospatial component. To improve the government’s land inventory, legislation known as the Federal Land Asset Inventory Reform Act (H.R. 1370, 109th Congress), has been introduced. This bill would “require the Secretary of the Interior to develop a multipurpose cadastre of Federal real property to assist with Federal land management, resource conservation, and development of Federal real property, including identification of any such property that is no longer required to be owned by the Federal Government, and for other purposes.”

5.4.2

State Coordination

Only 12 states administer digital parcel programs through a centralized state system. In most states there is no established organization to act as the coordinator of a statewide land parcel data set. While there are successful models, these programs are often the result of unique situations where strong leadership found the right issue and set of resources. In the remainder of states, additional leadership and strong incentives would be needed to encourage state participation. Even though NSGIC has become a recognized entity it has not tackled the issues relating to intergovernmental coordination that would be required for a parcel program. Most states do not have regulations that require a timely and consistent flow of information from local governments to state and federal agencies. In fact, many local governments resist sharing parcel-level information with state agencies unless it is required by statute. This leads to major discrepancies in the information used at different levels of government. For example, most states are not able to even maintain a current representation of incorporated boundaries. Only a few states provide coordination of this information to the Census Bureau for completion of the annual Boundary and Annexation Survey.

5.4.3

Personnel

Managing an integrated parcel data program would require a variety of technical skills at all levels. These skills relate to a range of tasks during the creation and maintenance of the parcel representation and the database management for the attribute information. There are serious questions about whether the labor force exists to handle the task. The U.S. Department of Labor identified geospatial-related occupations as one of the 12 high-growth employment sectors for 2000-2010, with employment in those occupations projected to increase from 8 to 29 percent over the decade (U.S. Department of Labor, 2003). There is also evidence that GIS use is increasing at the local government level. A 2003 survey of 1,156 local governments by Public Technology, Inc. (PTI, 2003) (now called Public Technology Institute) documented that GIS is an integral part of the work

environment of more than 75 percent of the respondents. A few important trends were identified in the survey (PTI, 2003, p. 8):

On the horizon, GIS technology will become a key component of every government applications system. In addition to the visual analysis of data, a key driver for enterprise GIS applications is that location is the connection point for the interoperability of disparate systems.

-

77 percent of respondents use GIS technology to view aerial photography.

-

70 percent use GIS technology to support property record management and taxation services.

-

57 percent of respondents use GIS technology to provide public access information.

-

41 percent use GIS technology to support capital planning, design, and construction.

-

38 percent use GIS technology to support permitting services.

-

38 percent use GIS to support emergency preparedness and response activities.

-

33 percent use GIS to support computer aided response activities.

However, despite this growth in the use of GIS, it is questionable whether many small local governments can attract employees to some environments at existing salary ranges. Only 23 percent of the respondents to a 2003 geospatial industry salary survey by URISA were employed by counties, and only 12.7 percent were employed in the assessor’s office where the vast majority of parcel data are created and maintained (URISA, 2003).3 An FGDC state survey found that attrition of GIS-skilled workers in smaller counties has become a big issue because the mapping person may not be making much more than minimum wage (Stage and von Meyer, 2006a, p. 18). Alternatively, GIS workers may be required to carry out multiple duties other than geospatial work. In a field that is in high demand, once people have gained skills, they often move to higher-paying jobs elsewhere. These findings suggest that workforce issues may be greatest at the primary source for parcel data creation and maintenance. In medium- and smaller-sized counties where personnel fulfill many functions there is little time available for parcel conversion work. Conversion and maintenance work is time consuming and requires attention to detail, and so is a risky area for multitasking.

A digital divide clearly exists with respect to the management of land parcel data. The lack of current GIS, database, and network support is particularly acute in rural areas. This isolation also pertains to a support network of other practitioners and colleagues engaged in similar work. A social support network of practitioners can often learn quickly from each other when access is easy. In rural areas an e-mail list server or technologies such as NetMeeting or GOTO Meeting (Citrix) can help but are less effective than face-to-face learning from neighbors.

5.5

POLITICAL CHALLENGES

In addition to technical, financial, legal, and organizational challenges, a national program of coordinating land parcel data faces many political obstacles. In fact, the lack of political will may be the most difficult hurdle of all.

5.5.1

Return on Investment

It is difficult to calculate a clear financial return on investment for developing a national program for parcel data. It is much easier to estimate the costs of a national parcel data set than to quantify its benefits. Some tangible benefits can be quantified, such as improved tax compliance and efficiencies within specific government agencies and private sector industries. However, these issues are unlikely to be persuasive by themselves when measured against the substantial cost to develop a national system. The real benefits of a nationally integrated system accrue to larger groups and to

|

3 |

See http://www.urisa.org/prev/store/salary_survey_2003.htm [accessed June 13, 2007]. |

society as a whole. These include fraud reduction, fairer assessments, improved decision making, more effective emergency management and response, and the improved economic development that better information can facilitate.

5.5.2

Motivation from Local Government

Much of the feedback from stakeholders in the parcel community suggests that local governments who operate digital parcel data programs have little motivation to participate in a national system, as illustrated by this comment:

At a local level, there is little to no thought of this as an issue. It is not important. We have and maintain the information that we need to conduct our business. If we need some info from an adjoining jurisdiction, I call my one of my friends and ask for a file, he sends it to me and vice versa. This is more of an issue for the state and federal levels of government. (Comment from web forum: Stephen Marsh, Director, GIS Department, Jackson County, Missouri Director)

For local governments that have invested in and built their parcel data systems there is a sense among a small percentage of them that their systems suit their own needs and they see little or no benefit from a “national” system. They assume that any system at a state or national level could never be as accurate or current as their own data and they rarely need to consolidate data with other communities. Furthermore, some are hesitant to “give away” data that their community has worked hard to finance and create. Even the most successful local government parcel programs will be reluctant to change existing practices to adopt a different federal standard. They view this as a drain on resources with no direct return. It is clear that strong incentives will be necessary to overcome this reluctance to provide data for a national land parcel system.

5.5.3

Distrust of Unfunded Mandates

Many local governments currently face serious budget restrictions, some because of property tax limitation initiatives. Funding for additional personnel or new projects is limited by the need to provide more services for less cost. Therefore, there is often distrust at the local level of federal initiatives, a distrust borne of past experience with unfunded mandates and the forced sharing of data with nothing in return.

The Census Bureau BAS [Boundary and Annexation Survey] survey is an excellent example. As a single resource GIS shop for my county, I am very busy and my immediate future is downright insane…. They assume, if there are a few changes, the survey could take about 20-40 hrs to complete…. If I care to submit digitally, I then have TONS of hoops to jump through. And all this hassle is for … what? Where is my incentive? Hopefully, next year I will have some staff and we can work on it. (Comment from web forum: David Weisgerber, Polk County, North Carolina, GIS Technician)

Another example is the Census Bureau’s Local Update of Census Addresses program as described in Chapter 4, in which locals must provide updated addresses but then are not allowed to use the updated Census files.

Unfortunately, the last 25 years have not had many demonstrated successes of intergovernmental cooperation. The federal government has struggled for years to create a national system of consistent geospatial information. Geospatial One Stop and The National Map have yielded only mixed results (NRC, 2003a; NACo and NSGIC, 2005), and the National Integrated Land System, as described in Chapter 4 is still in the prototype phase. There is a risk that a national land parcel data program will be viewed as just another “mapping program du jour” and will not be taken seri-

ously. The challenge is to clearly distinguish this program from the others and to highlight how this approach is more likely to succeed.

5.5.4

Private Sector Seen to Benefit at Expense of Local Governments

Many firms in the private sector are assembling parcel data for large parts of the country. These firms use parcel data to drive business applications or to provide better address matching (geocoding) services. Others are building real estate applications or serving as wholesale aggregators of land parcel data. While some of these firms provide revenue to local governments, there is widespread perception that they are simply harvesting data created by local governments for commercial gain, as the following quote from the stakeholder feedback illustrates.

It kills me when the private sector can make a fortune of a database that I have worked on for years. (Comment from web forum: James Myers, GIS Technician, Sedgwick County Court House, Kansas)

Some local governments will lose revenue from licensing fees if local data are available through a national system. Many local governments currently charge third parties for the use of their parcel data. In some cases, these charges are nominal and simply cover the cost of duplication. In others, the charges can be quite high because they are intended to recoup prior investments in expensive systems or even to be a source of revenue. For example, Dallas County, Texas, offers its digital parcel data for $50,000 and Nassau County, New York, sells its data for $40,000. These local governments may view a national parcel database as a “giveaway” to private companies and others who currently purchase the data directly from them.

5.5.5

Local Political Realities

Very few elected county commissioners and others who approve budgets have a strong background in technology, let alone geospatial technology. This makes it challenging for them to evaluate budget requests for technical items, especially when it involves funding the sharing and distribution of local government assets. A large budget request for a parcel conversion project therefore faces greater scrutiny and skepticism because the outcome cannot be foreseen. Clearly there must be significant financial incentives or state regulations to gain the participation of many local governments.

5.6

UNIQUE CHALLENGES OF CREATING PARCEL DATA FOR INDIAN COUNTRY

There are many unique challenges to creating a national parcel layer for Indian Country. These challenges can be divided into four areas: legal, political, social, and the juxtaposition between the tribes and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).

5.6.1

Legal and Policy Challenges

Many legal challenges affect the availability of parcel information in Indian Country. The primary area of concern is Code of Federal Regulations 25 Chapter 24 Section 2216, which sets restrictions on the availability of land ownership information. Technically the BIA or a tribe is not allowed to release this information. At this time special clearance is needed by users to access this database. A trust database has been set up by the Department of the Interior Special Trustee’s office. The system for accessing and inputting information is called Trust Asset and Accounting

Management System (TAAMS). However at this time TAAMS contains only tabular data about the allotments.

In addition, the ongoing Cobell v. Kempthorne litigation has increased the security for trust information. Cobell v. Kempthorne is a class-action suit brought against the U.S. government by Native American representatives, claiming that Indian trust assets have been accounted for incorrectly. One of the findings of the Cobell case is that the BIA has been unable to adequately track individual allotee names and that the prior system was insecure. Since individual allottee information is ultimately tied back to distribution of income derived by trust land, this database and its integrity are of great concern to tribal people.

Even at the tribal level there is a great desire to keep trust land information confidential. Tribes such as the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe in New York keep tight control of their trust information. Information is not permitted to leave the office, even for in-house projects.

5.6.2

Political Challenges

Public Perception

Another challenge to the release of information on parcels is related to the internal politics of the tribes. As mentioned earlier, many reservations have significant non-Indian ownership among the trust land on the reservation. However, the general public’s perception of Indian reservations typically comes from state highway maps and other maps that show the reservation as one homogeneous polygon. This has led individuals to believe that the entire reservation is composed of tribal trust land. Some people feel that depiction of the tribal presence as a reservation line bolsters tribal sovereignty more than displaying individual parcels or trust land.

Unwillingness of Tribes to Accept Current Delineations

Another concern tribes have with the release of land parcel data is that some tribes do not wish to accept the current land parcel delineations as defined by the federal government. In addition, there is fear that acceptance of those lands will set a precedent, or interfere with current land claims. Many tribes have ongoing land claim disputes across the United States.

Inability of Tribes and Counties to Work Together

Yet another difficulty that tribes face in the political arena is the inability to effectively work with county governments where counties also have some jurisdiction. This problem makes the creation of a homogeneous parcel layer across the reservation extremely difficult. Since trust lands are not taxed, some county officials see tribes as a burden on the tax rolls or even a threat. This is especially the case today when tribes have used gaming revenues to start buying back land on the reservation and convert it to trust land, essentially removing it from the tax base. Sometimes tribes may have better access to resources and training for creation of a GIS parcel database than do counties. This is because the tribes fall within the Department of the Interior’s licensing agreement for GIS software. This licensing agreement provides the complete suite of GIS software at no out-of-pocket cost to the tribes. This perceived technological advantage may be threatening to county governments. Tribes may have strong capabilities in GIS, but the real power of a parcel layer is in the owner’s names. Regular acquisition of parcel tabular data is necessary to make the parcel layer useful. Creation of a useful parcel layer is a team effort and requires tribes and counties to work together.

5.6.3

Social Challenges

Many tribes still have deep, conflicted feelings about land ownership and the creation of parcels for Indian Country. One statement commonly heard is, “How can you sell your mother?” In some native cultures the idea of carving up the landscape into parcels is very distasteful. This is not the case everywhere; however it is an issue that runs very deep.

5.6.4

Juxtaposition of Tribes and BIA

Lastly, the juxtaposition of tribes and the BIA when it comes to trust parcel mapping is a very interesting issue. On many reservations across the United States, the BIA plays a very minor role in mapping trust land in the local office. Many tribes have contracted the BIA roles on reservations (e.g., forestry, transportation, and land services) via Public Law 93-638 (Tribal Technical Assistance Program, 1994, pp. 1, 7). This has given the tribes better control of these types of programs on the reservations and has typically included some sort of GIS role occurring at a tribal level. On other reservations, parcel mapping services come from the BIA due to lack of local funding, skills, or interest. Tribal programs need up-to-date parcel information for management decisions, planning, development, and emergency response. This often includes mapping non-Indian lands on the reservation. As tribes have become more self-supporting and proactive in management, they have acquired finances to fund parcel data collection. Unfortunately, the BIA has a very low level of on-the-ground involvement on many reservations; hence there is no institutional need for the BIA to create up-to-date parcel data. The problem then becomes that the BIA is the “official source” of trust parcel mapping. However the data the BIA maintains are most likely not kept up to the standard needed and used by most tribes.

5.7

SUMMARY

In this chapter the committee has outlined the technical, data, financial, legal, organizational, and political challenges that would inhibit the creation of a nationwide program for parcel data. Although there seem to be numerous technical, data, and financial challenges, there are also numerous examples where these types of challenges have been overcome or resolved in particular communities or in other countries. Therefore, the committee believes that these types of issues are minor compared to the legal, organizational, and political ones. With more than 3,000 counties, tribes, and other local government entities as potential producers of parcel data, the organizational issues are complex. Also, other countries have created national land parcel data, which shows that it is feasible to do so. The next two chapters describe the committee’s vision for a national land parcel data system in the United States, and what needs to be done to overcome the challenges described in this chapter to achieve that vision.