5

Spread and Implementation of Research Findings

This session of the workshop consisted of two parts: how research findings and innovations are transferred among implementers in health care and what lessons can be learned from other disciplines. Perspectives from other disciplines included systems engineering, organizational change and development, and the history of medicine.

HEALTH PLAN PERSPECTIVE

This session focused on what is known about spread and implementation from health plans. While other perspectives are important, such as those of small providers and nursing homes, the planning committee chose to focus on health plans due to their leadership in this area and unique organizational structures. Speakers were asked to answer the following questions:

-

How do you spread research findings or other quality improvement strategies within and outside of your organization?

-

How are the innovations you implement identified? What types of evidence (e.g., clinical evidence, evidence on the innovation’s effectiveness, generalizability to your setting) are required before an innovation is chosen for implementation?

-

What methods are used to evaluate the success of implemented innovations?

Kaiser Permanente

Paul Wallace of Kaiser Permanente provided an overview of how Kaiser spreads research findings and chooses interventions for implementation. (See Appendix C for submitted responses.) The challenge is in balancing the tension between providing evidence-based care while providing care seen as relevant and important by both clinicians and patients. Kaiser operates in eight regions, giving rise to local issues, and provides care to 8.6 million members in a variety of settings. With hundreds of clinics, thousands of modules, tens of thousands of clinicians, and hundreds of thousands of employees, it is a challenge to balance both organized and “random acts” of quality improvement at the local level while implementing large national plans.

Kaiser Permanente is formally organized at both the national and regional levels. Certain core values are shared nationally and others locally. One national core value is the mutually exclusive relationship between Permanente medical groups and Kaiser health plans. Another core value is that all of Kaiser ’s physicians work for the Permanente Medical Groups and operate under capitated payment agreements with the Kaiser health plans, allowing for creative methods to pay for care innovations. The Permanente Medical Groups are multispecialty medical groups where specialists work closely with primary care physicians on a regular basis. Another national feature is Kaiser ’s overall governance, which includes a national board of directors for the health plan and an overall strategy developed jointly between the medical groups and health plan. One part of its national strategy is quality—including clinical quality, service, safety, and risk management. The Care Management Institute (CMI) was developed as a central place to share ideas about population-based care across regions. The CMI also houses formal networks for implementation and measurement.

Although consistent values are held nationally, organizational culture is largely a regional phenomenon, Wallace said. Each region and even each local office practices within its own locally evolved and defined culture. Locally, Kaiser ’s organizational cultures can largely be defined by regional medical groups that work together interregionally, but are considered separate entities running under separate budgets. The work of these medical groups is local, meaning in practical terms that “credit” for improvement is largely “owned” at the local level, despite the fact that Kaiser is a national organization.

Theoretically, ideas can flow through an organization either from the bottom up or from the top down. At Kaiser ideas flow in

both directions. In the bottom-to-top approach, some innovations begin in local clinics and/or research centers and spread to others within a region. National awards for quality recognize outstanding innovations and are presented to give innovators an opportunity to share ideas with others outside their local region. Some ideas can be approached from the top down, such as key priorities for improvement that are identified and promoted nationally. Using a case study, Wallace described how a unique innovation for cardiovascular risk protection spread in about 17 months. The literature showed that a few different pharmaceutical interventions each yielded incremental improvement in the occurrence of cardiovascular events. Using Archimedes, a modeling and simulation program developed by David Eddy, it was found that a new drug combination regimen was more effective in preventing major cardiovascular events in diabetics than the traditional approach of focusing primarily on diabetes glucose management. Using the results of the model, a financial case was made that prescribing generic aspirin, lisinopril, and lovastatin together could decrease cardiovascular death, myocardial infarctions, or stroke in high-risk patients, such as diabetics older than 50 years old, saving approximately $600 per person per year.

The regimen spread to other regions based largely on the evidence provided by the Archimedes model. Within 18 months, all Kaiser regions were actively involved in implementing the regimen. Each region tailored the regimen as needed, but the core innovation was implemented nationwide. Currently, it is also being spread outside of Kaiser to community clinics in California, which has anecdotally seemed easier than achieving spread within Kaiser. This spread has been largely because people immediately recognize its value, Wallace said.

From this experience and others, Wallace derived driving factors for innovation and successful spread. The first factor centers on credibility, earned through strong literature, previous successful implementation of the innovation, and a compelling business case. Spread also requires balancing the tensions of the intervention, reflecting true change but not being too disruptive or considered unorthodox. Paradoxically, a somewhat controversial intervention can stimulate discussion and lead to engagement. Another critical factor was that the intervention must be able to be modified at the local level. A fourth factor for spread was having available an established network that is experienced with spread of innovation and ensuring that the innovation will fit with the network’s strategies, much like Plsek’s attractors. Although it is not a certainty that the spread of this drug regimen could be replicated with other interventions, Wallace said,

the most critical factors in this example potentially were the leveraging of multiregional formal networks and of people whose jobs were to outline and locally pursue implementation and associated performance measurement. The final contributor to spread of innovation was luck in terms of timing, alignment with developing priorities, and availability of funding.

Aetna

David Pryor of Aetna described Aetna’s engagement in care management and quality improvement. (See Appendix C for submitted responses.) Aetna is a health benefits company serving 15 million members nationwide through large plan sponsors and employer groups. Aetna sees itself as a partner with its employees and members in improving the quality of care. Of particular interest are understanding best practices and leveraging technology to assist in the practice of evidence-based medicine. Aetna also focuses on consumer engagement, exemplified in its leadership with consumer-driven health plans.

Aetna’s approach to quality improvement builds on the IOM’s six aims for quality: care should be safe, effective, patient centered, timely, equitable, and efficient (IOM, 2001). Pryor noted that it was particularly important to balance efficiency with the other quality aims. Opportunities for quality improvement are identified in several ways. One method detects gaps in care by assessing data collected from surveys. For example, HEDIS scores are measured for care provided (e.g., preventive health screenings and chronic care treatment) through all of Aetna’s regions. If performance is below standard in an area, it becomes an opportunity for quality improvement. Aetna made improving maternity care a priority when it realized HEDIS scores were sub-optimal in selected areas. As a result, Aetna’s maternity care program became more comprehensive, offering a full range of maternity services for families contemplating or expecting children. In addition, Aetna has developed programs aimed at addressing quality and efficiency in neonatal intensive care unit care.

A second approach to quality improvement identifies gaps from external data analyses. This approach has been used in addressing health care disparities. Through its breast health initiative, Aetna developed an RCT to assess improvements in mammography screening rates among African American and Latina women. Conducting external scans of the environment is another method Aetna has used to identify disparities and opportunities for change.

A third method used to identify opportunities derives from collaborations with internal and external constituencies. Aetna has increasingly gained leverage when working collaboratively with large employer groups to improve quality for employees and reduce costs. Aetna worked with Virginia Mason Hospital and Medical Center to improve treatments of low back pain by relying less on advanced imaging processes and instead has focused on tracking patients into physical therapy treatments sooner in the process. The improvement resulted in savings for employer groups and insurers, and Aetna worked with the hospital to minimize the adverse impact of reduced reimbursement from imaging studies.

Aetna also surveys the Medical Network Trend Operating Report, which focuses on costs, utilization, and the economic impact of practice patterns. This approach was used to improve monitoring of anesthesia during colonoscopies. It was found that anesthesiologists did not need to be present for certain routine procedures and that the proper adjustment to staffing could greatly decrease costs without negatively impacting patient safety during the procedure. Improving quality while also improving efficiency is a concept at the heart of Aetna’s medical management philosophy and one does not have to be sacrificed for the other, Pryor said.

The role of technology to improve quality is also critical. Aetna uses a robust data warehouse called Active Health Management to compile many different types of data about each of its members. Data can be aggregated at all levels to help assess care delivery.

Pryor discussed three influencing factors of implementation. First, the impact on membership and size is a key consideration that drives Aetna’s focus on improving chronic disease care. The second factor is customer buy-in and support, where Aetna, as an insurer, can monitor customer preferences and can determine how to pursue those preferences if they fit into the company’s vision. The last factor for implementation is feasibility, which is especially important in Aetna’s structure, where physicians are independent from the company.

To evaluate their quality improvement efforts, Aetna studies measures of performance and return on investment. Some programs have relatively easily measurable metrics (e.g., hemoglobin A1c levels in diabetics), but others are much more difficult (e.g., return on investment and efficiency). The return on investment measure is an area receiving particular attention in the company because it is being asked for by many employers or plan sponsors, but it is not always a factor used to determine whether an intervention should be implemented.

Information about quality improvements is shared both internally and externally to encourage spread of best practices. While many efforts begin with top management, some begin within local markets and spread to others. One method for internal sharing is Aetna’s internal website, where new information is posted daily. Externally, Aetna participates in a variety of industry associations, such as America’s Health Insurance Plans and the Disease Management Association of America. All stakeholders must be involved, including academia, the private sector, and employer groups. Partnerships are imperative to providing evidence-based, high-quality care.

PERSPECTIVES FROM OTHER DISCIPLINES

The forum invited speakers from engineering and organizational change and development to discuss the role research has had on spread in their disciplines. These speakers were asked to respond to the following questions:

-

In your area of research, how are findings and best practices spread? What lessons can be leveraged from your experiences?

-

What methods are used to evaluate the success of implemented innovations?

-

Due to the high levels of variability between patients and health care systems, how should this variability be considered in assessing implementation?

To better characterize health care, the perspective of a historian of medicine was also sought. Although the planning committee recognized the importance of other disciplines, the workshop was limited in the number of speakers.

Engineering

Improvement can be viewed as getting better at things already being done, said Bill Rouse of the Georgia Institute of Technology. From a systems perspective, mere improvements will not be sufficient to address the problems facing health care. Instead, the focus should be on innovation, the creation of change.

Rouse identified a number of sources for best practices. When identifying best practices, inventions must be differentiated from innovations. As creator of change, innovation is related to patterns in data, processes, and improvement, among others. Invention and

innovation involve the discovery of patterns, as identified by data in a broad sense that work and are adopted widely. From a multidisciplinary perspective, it has been found that basic behavioral and social processes are fundamental to the adoption of discoveries for all people and disciplines. Innovation occurs either from the inside out or the outside in. Inside-out innovation refers to those changes driven from internal sources and tested in a market; in this type of innovation, patterns are created. This is the type of innovation largely discussed during the workshop. Outside-in innovations are those where patterns are exploited—practices across other sectors and industries are identified and brought into a new industry. From a systems perspective, a balance between inside-out and outside-in innovations should be sought.

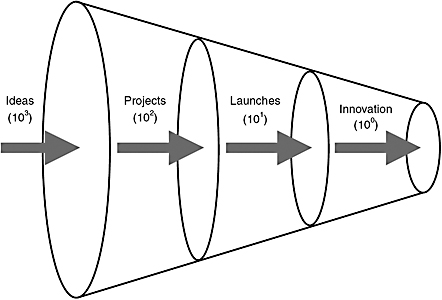

Rouse bridged four lessons from other industries into health care. The first lesson was the notion of an innovation funnel (Figure 5-1), aimed at answering the question of how many ideas are required to get one fundamental change into the marketplace. Although the literature varies, Rouse gave the following example: A thousand ideas can lead to about a hundred projects, leading to launches on the order of tens of new products, one of which will fundamentally change the market. The challenge is to sift through the thousands of ideas to find the innovation.

FIGURE 5-1 Innovation funnel.

How 80–85 percent of American companies sift through ideas was Rouse’s second lesson: having multistage investment strategies where investments are made in many small ideas. Evaluation of multistage strategies will be discussed later.

The third lesson, bridged from financial markets, leverages the use of options for investment. This lesson requires that dollar values be determined for a technology or idea. Like stock options, once a company decides to fully invest in an innovation, it would have the flexibility to use the idea immediately or at a later date.

The fourth lesson comes from a session with IBM, where it was recognized that health care is an incredibly complex system with nobody in charge, Rouse said. To address this issue, an online game was created called Health Advisor. In the game, 10,000 11-year-olds would manage a variety of patients in the health care system. The expectation is to find one or two good ideas out of 10,000.

Innovations can be evaluated using a number of approaches. First, innovations may be assessed in stages, using multistage criteria to consider the innovation. Multistage criteria include strategic fit, payoff, resources, application risk, and personnel. These criteria must be explicitly stated so that the innovators know how they are being measured. Balanced scorecards may also be used to evaluate innovations. A third method for evaluating innovations was by human-centered design, a process that considers and balances the concerns, values, and perceptions of all the stakeholders in the process. This occurs through a number of phases that include getting to know stakeholders and their needs as well as their reactions to new ideas.

Rouse identified a number of methods for considering variability. First was a continuation of the above-described human-centered design with understanding stakeholders as the focus. Another method for handling variability is the staging of investments to hedge risks. Rouse also proposed the use of options-based valuation to protect investments in innovations. The last method suggested was use of process controls to limit variations in subjects.

Organizational Change

Simple behavioral changes, such as folding your arms the other way, are awkward to make, said Newton Margulies of the University of California, Irvine. Change is difficult, resistant, and often feels wrong. Inducing major change in large organizations is much more difficult than simple behavioral changes because organizations themselves are problematic. Additionally, most organization designs

are outdated and do not reflect current environments, requiring more comprehensive organizational change.

There is a process in which change occurs, beginning with collecting data, making a judgment or diagnosis, and deciding on the appropriate change intervention to use. Although the process is known, it is rarely implemented, causing change to be cumbersome and slow. Various definitions are often used for change and include planned change (a process and a technology aimed at improving the health and performance of an organization), organizational development (the continuous application of a single or several techniques focused on improvement), organizational transition (planned change from current state to future state where the future state is reasonably well defined), and organizational transformation (planned change from current state to future state where the future state is emerging and is not clearly defined). All these concepts are becoming increasingly common and better understood in organizational change.

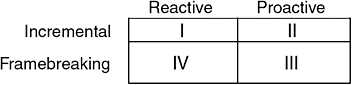

Margulies presented two sets of categories for change, the first being reactive and proactive change. Reactive change is change stimulated by a force and focuses on the present (e.g., change in chief executive officer leads to changes throughout the organization). Proactive change is stimulated by strategic vision and focuses on the future. Another set of change categories presented was incremental and framebreaking change. Incremental change consists of making small improvements, whereas framebreaking change requires major shifts in the mission, value, and process of an organization, leading to a different culture. Combining these sets of categories creates a matrix with four phases of change (Figure 5-2).

Phase I is reactive, incremental change—something occurs and a small change is made—which is mostly done well. The type of change that tends to fail is reactive, framebreaking change (Phase IV). In Phase III, proactive framebreaking change, there is time to prepare and plan for transition for major shifts, but not so in Phase

FIGURE 5-2 Phases of change.

IV. This matrix can also help an organization determine the amount of time and resources generally necessary for a particular type of change, Margulies said.

To ensure successful implementation of change, Margulies offered several tips. The first tip was that communication is a major factor for change. Communication includes not just disseminating what the change is, but the purpose, the plan, and end goal as well. Development of a plan for communication itself is encouraged. The second tip noted that there must be strong communication between senior management and change teams. Margulies also discussed the need to thoughtfully balance planning for change and urgency of implementation. A carefully thought-out plan for change is critical and often does not occur. The fourth tip highlighted the need for transition planning. The biggest failure in change implementation is the lack of careful transition planning, Margulies noted. The fifth tip stated that engaging participation from those affected by change is critical. The sixth tip was to carefully consider culture change. Development of a clear communication and commitment plan was the seventh tip. Finally, appropriate resources must be allocated and applied.

History of Medicine

History is the ultimate outcome, noted Guenter Risse. (See Appendix C for submitted response.) Historians are the students of change and are responsible for interpreting and articulating change, often through stories. Imperative to change is understanding context, Risse said. Stories are contingent on context and therefore must be translated before they can be applied. For lessons to be broadly generalized, commonalities must be found among organizations.

Risse introduced the notion that hospitals are houses of rituals. Often irrational institutional routines and inefficiencies can be viewed as barriers to care. These seemingly unnecessary routines are often remnants of long traditions that are deeply embedded in the culture of medicine. Culture moves slowly, but to be changed effectively, traditions or rituals must be acknowledged and considered. Rituals can also be used as framing devices to identify distinctive, deliberate actions to express and reaffirm values, beliefs, and relationships. The goal of rituals is to structure reality and provide cohesion to sequences of acts in life. Some rituals are shared, while others are not. They are constantly being created as ideas and environments change. One example of rituals is communication because it depends on very ordered, patterned sequences. Health

care processes rely on communication. Elementary healing processes rely on cultural symbols that address emotional aspects of sickness such as restoring a sense of control and order by communicating with the divine. Diagnoses and treatments are no longer viewed as punishment by divine retribution for the sick or a form of social retaliation.

Health care has been transformed into a commodity. Care is currently viewed as a type of service where patients are labeled consumers and hospitals are considered corporate entities. Corporate culture encourages and rewards creativity, innovation, and risk taking. However, rituals of corporate life in hospitals are yet to be examined. Better understanding for these rituals would help contribute to the understanding of organizations and help yield better outcomes.

Health care is not just about cost cutting; it is about respecting patients and caregivers. Patients are often treated as ignorant, but it is no longer applicable to treat patients this way, especially with the increase of information available to patients on the Internet. Understanding the meaning of the ceremonies in health care can help serve as a reminder of the humanity of health care institutions, Risse said.

Open Discussion

Audience members were invited to ask questions. One question posed to Pryor and Wallace asked how grassroots participation is integrated into management to sustain change, given Aetna’s limited control of its affiliated independent physicians as well as Kaiser ’s group and top-down constructs. At Aetna, engagement at the physician specialty group level is critical. A main leverage point for new policies is attaining buy-in from professional societies such as the American College of Gynecology and the American College of Physicians, Pryor said. Wallace supported Pryor ’s statements, adding that benefits must be framed in concrete terms when considering new policies. Often, the best way to frame opportunities is from the perspective of patients, Wallace said. There is a growing need to understand social networks within care environments to determine whether a physician’s primary affiliation is with, for example, the American College of Surgeons or the hospital (e.g., “What tribe are you in?”). Being aware of these affiliations may hold implications for spread and implementation, Wallace noted.

The next question asked what the research and development budget should be in health care. Some provided specific plans for

finding this money, noting the total amount is considerable once investments in technologies are included. The cost of improving quality must be considered in the context of financial realities, one speaker noted. Another speaker also recognized that the health care system is not value reimbursable, but is cost reimbursable, which provides little incentive for innovation. The bottom line was that evaluation should be a byproduct and an expected consequence of care. Marginal activities to conduct evaluations would be counterproductive in this sense. Although evaluation is not currently a byproduct of health care, it may not be far off, given the evolution of data systems.

Responding to a question about the role of private payers to recognize the costs of quality improvement, to manage innovation, and to ensure sustainability, one speaker identified innovative collaboration as key. One type of collaboration is the formation of partnerships with academic institutions to obtain data and subsequently perform studies on those data. Pay-for-performance initiatives were also mentioned as a method to provide incentives for quality improvement.

The last question asked during this session was about publication in peer-reviewed journals as the traditional vehicle for dissemination, recognizing that many nonacademic institutions do not publish articles. One speaker noted the difficulty in publishing articles if data are collected from multiple sites around the country because approval from multiple IRBs would need to be obtained. For the effort required to publish articles, given the questionable value added to nonacademic institutions, the marginal costs would likely be substantial. Peer-reviewed articles are successful vehicles for spread for those who write papers, but are not always useful to those from an operational context. Other methods participants noted for disseminating knowledge and ideas were the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s annual meeting and the general media.