Appendix C

Submitted Responses

Speakers in the “State of the Science of Quality Improvement Research” and “Spread and Implementation of Research Findings” sessions were asked to respond to specific questions. Some speakers opted to submit written responses to those questions in addition to their comments during the workshop. The planning committee also invited Richard Grol, a researcher who could not attend the workshop, to submit written answers. This appendix is devoted to speaker responses.

STATE OF THE SCIENCE OF QUALITY IMPROVEMENT RESEARCH

Trish Greenhalgh

1. With respect to quality improvement, what kinds of research/evaluation projects have you undertaken/funded/reviewed? In which contexts (e.g., settings, types of patients)? With whom do you work to both study and implement interventions? For what audience?

I am an academic at University College London. In my talk I will describe two projects (out of a much wider portfolio) that illustrate the kind of work I do in quality improvement (QI). These projects are (1) a study of primary care interpreting services in a multiethnic area of London, and (2) a recently commenced study of Internet-based electronic patient records across the United Kingdom.

2. How do you/does your organization approach quality improvement research/evaluation? What research designs/methods are employed? What types of measures are needed for evaluation? Are the needed measures available? Is the infrastructure (e.g., information technology) able to support optimal research designs?

My take-home message is that QI research is currently under-theorized and would benefit from the application of a much wider literature—such as from mainstream organization and management research. There has been far too great a focus on “what works” and too little emphasis on “why might X work (or not work).”

3. What quality improvement strategies have you identified as effective as a result of your research?

See response to previous question. If you asked instead, “What key theoretical approaches have you found that illuminate the process of quality improvement?” I would say there are many powerful theories out there in the literature, and there’s nothing as practical as a good theory. In my talk, and just as an example of the rich pickings available, I will briefly introduce the work of Martha Feldman on organizational routines, which I think would add huge value to current work in health care on “implementation.”

4. Do you think the type of evidence required for evaluating quality improvement interventions is fundamentally different from that required for interventions in clinical medicine?

a. If you think the type of evidence required for quality improvement differs from that in the rest of medicine, is it because you think quality improvement interventions intrinsically require less testing or that the need for action trumps the need for evidence?

b. Does this answer depend on variations in context (e.g., across patients, clinical microsystems, health plans, regions)? Other contextual factors? Which aspects of context, if any, do you measure as part of quality improvement research?

I’m not sure I’d frame the question this way. There’s a fundamental difference (but also some commonalities) between research and evaluation. I recommend Michael Quinn Paton’s book on Utilization Focussed Evaluation. I think QI work has many parallels with evaluation work. Some ideas:

-

In general (but not universally), research is systematic inquiry directed at producing generalizable new knowledge. It is explicitly conclusion oriented (we look for the “findings” of research, and for its “bottom line”).

-

Evaluation (and much QI work) is decision oriented and (hence) utilization oriented. Its goal is to inform decisions, clarify options, identify areas for improvement, and support action. Creation of generalizable knowledge may occur as a “byproduct” of evaluation (and of QI), but it is not its primary output.

-

In evaluation (and in much QI work), the sociopolitical context of the project or program is explicitly factored in, whereas in most research, it is controlled for or otherwise “factored out.”

-

In evaluation, as in research, measurement is important but in evaluation, the decision about what to measure requires context-specific value judgments about what is important (what has merit, what we care about). Evaluation concerns itself centrally and systematically with identifying what is important to the actors and stakeholders, and in developing approaches to measurement that are designed to produce the data needed for particular judgments by particular actors and stakeholders in particular contexts. Scriven has captured this key feature of evaluation as follows: “the key sense of the term ‘evaluation’ refers to the process of determining the merit, worth, or value of something, or the product of that process. The evaluation process normally involves some identification of relevant standards of merit, worth or value; some investigation of the performance of evaluands on these standards; and some integration or synthesis of the results” (Scriven, 1991).

These differences notwithstanding, research and evaluation also have much in common. In particular:

-

Both research and evaluation benefit from theory-driven approaches that can guide the collection and analysis of data. Just because evaluation is not primarily oriented toward producing generalizable findings does not make it a theory-free zone.

-

Both research and evaluation require definition of data sources, meticulous collection and analysis of data (using appropriate statistical tests or qualitative techniques), and synthesis and interpretation of findings.

-

Both research and evaluation may be approached from an “objective” epistemology (which assumes that there is a reality “out there” that can be studied more or less independently of the observer) or a “subjective” one (which holds that there is no “view from nowhere” and that the researcher ’s identity, background, interests, affiliation, feelings, and other “baggage” not only unavoidably influence the findings, but may themselves be viewed as data).

-

Both research and evaluation may use quantitative meth-

-

ods, qualitative methods, or a combination of both. Both may also employ participative approaches such as action research.

-

Both research and evaluation may employ a variety of approaches to engage stakeholders, gain access to data sources, and involve staff and service users.

-

Both research and evaluation require informed and ongoing consent from participants.

5. Do you have suggestions for appropriately matching research approaches to research questions?

I think the fundamental bridge to cross here is to understand the difference between research (oriented to generalizable conclusions) and evaluative approaches (oriented to context-specific decisions). See above. Where QI researchers get tied in knots, I think, is in the well-intentioned but fundamentally misplaced drive for “generalizable truths about what works.” There are few truths, and even those that exist are always contingent and ephemeral.

6. What additional research is needed to help policy makers/ practitioners improve quality of care?

I’d put my money on the study of policy making itself.

Kaveh G. Shojania

1a. With respect to quality improvement, what kinds of research/evaluation projects have you undertaken/funded/reviewed?

The bulk of my work has involved conducting literature syntheses to compile and critically assess the evidence for the effectiveness of interventions to improve health care quality and safety. For instance, while at the University of California, San Francisco, I led the efforts of 40 researchers from 10 academic institutions to produce, for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), a compendium of systematic reviews of the evidence supporting more than 80 specific interventions aimed at improving patient safety (Shojania et al., 2001). This report gathered and assessed the evidence for interventions that ranged from very clinical safety practices (preventing common infectious and noninfectious complications of hospitalization, as well as uncommon but egregious ones, such as wrong-site surgery) to information technology solutions such as computerized provider order entry (CPOE) and bar coding through to more “safety science” strategies such as human factors engineering and root cause analysis. More than 125,000 copies of the full report have been downloaded or obtained in hard copy since its

release in 2001, and a pair of commentaries on the report appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Association (Leape et al., 2002; Shojania, 2002).

I have conducted similar syntheses of the evidence in the field of quality improvement, assessing the evidence for interventions designed to improve care across a range of conditions and settings, as part of a series of evidence reports for AHRQ (Shojania et al., 2004). Most noteworthy was the evidence synthesis for improving outpatient care for patients with type 2 diabetes (Shojania et al., 2006a). Using data from 66 clinical trials, we showed that the single most effective type of quality improvement intervention consisted of case management in which nurses or pharmacists played an active role in coordinating patients’ care and were allowed to make medication changes without having to wait for approval from physicians. The negative results of this analysis were also very important, as they emphasized the extent to which most quality improvement interventions conferred quite small to modest gains in glycemic control, even if they showed more substantial improvements in processes of care.

I present some of the details of the above research rather than just describing what kinds of projects I have been involved with because many do not regard evidence synthesis as a type of research in itself. However, synthesizing the literature can—in addition to providing a valuable resource for practitioners, policy makers, and other researchers—yield results that were not previously clear from primary studies, as with the example of case management for diabetes. Although case management has received considerable attention, previous studies and writing on the subject had not highlighted the fact that even very labor- and resource-intensive case management interventions tend to have small effects unless they include this key ingredient of some authority for case managers to make management changes, rather than just sending recommendations to physicians.

Though I am still engaged in evidence synthesis work related to patient safety and health care quality, I have more recently become involved in leading an extensive qualitative research project in which we are interviewing senior administrators, physicians, nurses, pharmacists, patient safety officers, and information technologists at hospitals across Canada in order to identify barriers and facilitators in efforts to implement three widely recommended patient safety interventions. I have also participated in several studies led by my colleague in Ottawa, Dr. Alan Forster, to improve methods for detecting safety problems using a variety of techniques, ranging

from prospective, active surveillance by trained observers of care (Forster et al., 2006) to automatic detection of likely adverse events based on natural language search engines applied to discharge summaries and other text-based aspects of the medical record (Forster et al., 2005). Lastly, in follow-up to a previous evidence synthesis that focused on clinically significant diagnostic errors detected at autopsy (Shojania et al., 2003), I am piloting a project to detect important diagnostic discrepancies among patients who undergo surgery or biopsies, rather than studying only those patients who have died and undergone autopsy.

1b. In which contexts (e.g., settings, types of patients)? With whom do you work to both study and implement interventions? For what audience?

Most of my work has focused on the hospital setting, as my clinical expertise primarily involves acute care, hospital-based medicine. In the past, I typically worked with other researchers and physician clinicians, but now work with several senior hospital administrators and more frequently collaborate with nurses and pharmacists. Funded research for patient safety and quality improvement in Canada tends to come with requirements for “matching funds” (much of which typically come from the investigator ’s health care organization), so my research has necessarily involved closer ties with my hospital’s administration. However, the Ottawa Hospital has also taken a special interest in patient research, funding its own Center for Patient Safety with a budget of approximately $100,000 per year. So, several senior administrators are more open to collaboration on research projects than is probably the case at most hospitals.

2. How do you/does your organization approach quality improvement research/evaluation? What research designs/methods are employed? What types of measures are needed for evaluation? Are the needed measures available? Is the infrastructure (e.g., information technology) able to support optimal research designs?

One of the reasons I have not participated in research that directly studies my hospital is precisely the lack of readily available data and inadequate information technology (IT) infrastructure. My colleague at the Ottawa Hospital, Dr. Forster, has made great strides in building a so-called data warehouse, which will greatly facilitate efforts to characterize safety and quality problems in the hospital, and possibly even provide reasonable outcomes for some intervention projects.

We are implementing a CPOE system at our hospital over the next few years, which will also facilitate conducting research in quality improvement and patient safety. In the meantime, however, most hospital resources that could have gone into specific safety or quality research projects are consumed by the development and implementation process for CPOE. Thus, while I have a large externally funded grant to study CPOE implementation across Canada, I am mostly staying away from in-depth research in my own hospital until we actually have a CPOE system successfully in place, which may not happen for 5 years or more.

3. What quality improvement strategies have you identified as effective as a result of your research?

The short answer is that no strategy works particularly well, and even the ones that work modestly well do not necessarily generalize to multiple quality targets or across clinically distinct settings (Shojania and Grimshaw, 2005). This should not be misconstrued as saying that nothing works. The key is to recognize that, while many people expect dramatic interventions to more or less solve quality problems, QI interventions resemble interventions in the rest of medicine—they tend to work modestly, not confer dramatic breakthroughs, and they tend to work with specific types of patients and/or in some settings better than others. So, just as no “one size fits all” pill will cure all ailments in clinical medicine nor any general lessons about “what therapies work” guide clinicians across the whole of medicine, there is no general lesson about what works in all of quality improvement. The specific quality problem matters, as do features of the patients, providers, and organizations involved, just as the specific disease and patient population matter in clinical medicine.

Some would argue that there are certain useful rules of thumb, such as multifaceted QI interventions work better than single-faceted ones, or “active” strategies work better than passive ones, but even these have proved not so clear-cut on close examination. For example, in our review of diabetes QI interventions (Shojania et al., 2006a), multifaceted interventions worked no better than single-faceted ones, a result replicated in a similar review of QI strategies for hypertension care (Walsh et al., 2006).

4. Do you think the type of evidence required for evaluating quality improvement interventions is fundamentally different from that required for interventions in clinical medicine?

An emphatic “No”! Arguments by those who would answer in

the affirmative comes in three main forms, which I briefly summarize and respond to below.1

-

The need to improve is so urgent that action trumps evidence.

Many regard the need to improve care as so urgent that, even if they feel QI is not fundamentally different from the rest of medicine, they feel we cannot afford to submit candidate interventions to the same type of evaluative rigor carried out in the rest of clinical research. It is surprising how commonly one hears this argument, since clinical research has always had as its goal the saving of lives. Researchers in cardiovascular medicine, oncology, HIV/AIDS, and many other diseases can claim numbers of lives lost each year to these diseases that match (if not exceed) “quality problems.” Why would we exempt research in QI from scientific standards that we routinely apply to the leading causes of morbidity and mortality?

-

Some QI interventions are so obviously beneficial that evidence is not necessary.

First, very few interventions truly have such self-evident benefit, but even if they did, and even granting the perceived benefit as real, there will always be a need for evidence about implementing interventions. For instance, handwashing for providers is generally regarded as a simple, obviously beneficial practice, yet interventions designed to increase handwashing are anything but straightforward and typically produced modest (at best) results.

A patient safety example involves the removal of concentrated potassium chloride (KCl) from clinical areas, which represents an “obviously beneficial” intervention to prevent fatal, iatrogenic hyperkalemia. Instead of relying on the vigilance of providers not to confuse concentrated KCl with other medications that have similar containers, simply remove it from clinical areas and make it available only in the pharmacy. This intervention represents a so-called “forcing function” because it supposedly prevents the wrong thing from occurring. In practice, however, because the error involved is so rare that the vast majority of providers have never seen it, they simply view this intervention as an annoyance, leading to a high potential for “workarounds.” For example, after concentrated KCl was removed from the general floors of one hospital, ward personnel could not obtain potassium solutions from the pharmacy quickly

-

enough to meet their patients’ needs. Some of them began to hoard intravenous potassium on their floors. Pharmacists were forced to chase after these hidden stashes, and intensive care units (which were allowed to continue to stock KCl) quickly became de facto satellite pharmacies, informally distributing concentrated KCl to ward personnel (Shojania, 2002). Thus, the simple and obviously beneficial “forcing function” not only failed to force the desired result, it led to an even more hazardous situation than before, since front-line personnel were now handling and administering concentrated KCl in an uncontrolled and potentially chaotic fashion.

-

Even when an intervention is as beneficial as it appears, evaluation will be required to ensure that implementation has occurred as expected and achieved the desired results.

-

Quality improvement interventions do not have side effects, so they do not require the same level of testing applied to drugs and other clinical therapies

There are two ways in which this view proves false. First, many quality improvement interventions, by their nature, involve delivering more care to patients (e.g., more patients receive treatment for their hypertension or diabetes), so an increase in complications of care (not to mention costs) is definitely possible.

For example, only 12 of 66 trials of strategies to improve diabetes care reported rates of hypoglycemia (Shojania et al., 2006a). However, 7 of those 12 studies reported more frequent hypoglycemia in the group receiving the quality improvement intervention.

Hypoglycemia represents an easily anticipated consequence of efforts to intensify diabetes care, but adverse consequences of many other improvement efforts have been less predictable, including errors introduced by computerized provider order entry (Koppel et al., 2005; Campbell et al., 2006; Ash et al., 2007), bar coding (Patterson et al., 2002), and infection control isolation protocols (Stelfox et al., 2003). Side effects may seem inherently less likely with quality improvement interventions than with drugs and devices. However, most quality improvement interventions involve changes to the organization of complex systems, where the law of unintended consequences—long recognized as a side effect of complex change—tends to apply. The potassium chloride example above provides just such an example. Another recent example is the reduction in work hours for postgraduate medical trainees. The intended goal is to reduce errors due to fatigue. However, reducing work hours inevitably involves creating new opportunities for errors due to increased handoffs between providers (not to mention potential

-

educational impacts and impacts on work for supervisors) (Shojania et al., 2006b).

-

In addition to adverse unintended consequences with direct potential for harm, quality improvement initiatives can consume substantial resources. The time and money spent implementing costly and complex interventions such as work-hour reductions or, for instance, medication reconciliation could have been spent on other interventions, including moderately costly, but definitely effective interventions, such as hiring more nurses (Aiken et al., 2002; Needleman et al., 2002) and pharmacists (Leape et al., 1999; Kucukarslan et al., 2003; Kaboli et al., 2006).

-

Quality improvement needs to draw on fields outside traditional clinical research, such as psychology and organizational theory, and needs to pursue other methodologies, such as qualitative research.

This is true. Importantly, however, psychology, organizational theory, and results from qualitative research represent the basic sciences of QI, not the methods for evaluating candidate interventions. Thus, the paradigm that I and others (Brennan et al., 2005) think needs to merge is one in which QI and patient safety have the same overall approach to moving from basic research through to initial trials through to large, well-designed Phase III trials, as in the rest of clinical medicine. However, the basic sciences in QI happen to be psychology, organizational theory, and human factors research, not molecular biology and physiology.

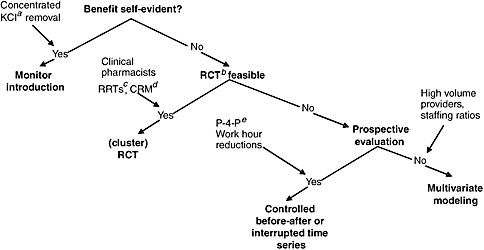

Research in these basic sciences of QI may involve using qualitative research techniques or mixed-methods research techniques. However, in order to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions designed on the basis of such research, we need a framework more or less the same as we do elsewhere in medicine. That said, not all evaluations need to involve randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The figure below (Figure C-1) provides a framework for thinking about the decision of how to evaluate a candidate QI intervention, especially one that would be recommended for implementation at more than one site.

But clinicians have often used therapies without good evidence; why should this be any different?

This is an interesting point. In fact, the rise of evidence-based medicine in some ways represented a response to the fact that physicians have often applied therapies and other processes of care that had little evidence and even varied widely in their tendencies to do so, often with striking geographic variations, as first shown by Wennberg and colleagues (Wennberg and Gittelsohn, 1973;

FIGURE C-1 Framework for evaluating the needs for evidence for candidate quality improvement interventions.

aKCl = potassium chloride.

bRCT = randomized controlled trial.

cRRT = rapid response teams.

dCRM = crew resource management (a type of teamwork training).

eP-4-P = pay for performance.

-

Wennberg and Gittelsohn, 1982). However, such variation and the use of unestablished processes of care has generally been regarded as a problem. When the stakes are high (potential harm to patients, consumption of substantial health care costs), large trials or other efforts to assess effectiveness have typically ensued. When conclusive evidence about a practice has not emerged, we tend not to regard the practice as “established” or “standard of care.”

-

Thus, in the case of QI, individual hospitals may pursue promising strategies on the basis of scant evidence, including results of early “basic research,” anecdotal reports of success, or face validity. However, just as clinical practices based on such limited evidence would never become broad standards of care, much less mandatory for accreditation or reimbursement, so with quality improvement: Widely disseminating a given QI strategy would require evidence in much the same way we would require in the rest of clinical medicine.

4a. If you think the type of evidence required for quality improvement differs from that in the rest of medicine, is it because you think

quality improvement interventions intrinsically require less testing or that the need for action trumps the need for evidence?

4b. Does this answer depend on variations in context (e.g., across patients, clinical microsystems, health plans, regions)? Other contextual factors? Which aspects of context, if any, do you measure as part of quality improvement research?

I have more or less answered this question in my responses above.

5. Do you have suggestions for appropriately matching research approaches to research questions?

I think the framework I have outlined (in Figure C-1) helps with this. Traditional cost-effectiveness considerations will also help. Most QI interventions achieve small to modest effects, and they require resources to achieve what impacts they do have. As with any clinical therapy, therefore, there is a cost–benefit decision to be made (Mason et al., 2001). For instance, in order for a solution to the problem of resident work hours to be cost-effective, it would need to improve care more than any published safety intervention (Nuckols and Escarce, 2005).

6. What additional research is needed to help policy makers/practitioners improve quality of care?

There is no single answer to this—the simple answer is that “more research is needed.” This may sound like a standard line from a researcher, but I think it’s crucial that we adjust our expectations for the field. We’ve been fighting the War on Cancer for more than 30 years now. This has required hundreds of billions of dollars to produce small, but steady and incremental gains. Expecting dramatic advances in QI on the basis of 5–10 years of research funded at a fraction of the cost and with far less sophistication and rigor will serve no one’s interests.

Richard Grol

1. With respect to quality improvement, what kinds of research/evaluation projects have you undertaken/funded/reviewed? In which contexts (e.g., settings, types of patients)? With whom do you work to both study and implement interventions? For what audience?

I believe that our research center (Centre for Quality of Care Science) is one of the largest centers in the world focusing specifically on quality improvement research and development. More than 40 Ph.D. theses have been finished in the past 10 years. Currently more

than 60 Ph.D. projects focus on quality assessment and improvement in different settings: acute hospitals, primary care, missing care, allied health, emergency care, after-hours care. The studies address different aspects of quality and safety improvement and the implementation of change, c.q. clinical guideline development and implementation, development and validation of (performance) indicators to measure change and improvement, analysis of barriers and incentives related to improvement of quality and safety, effectiveness of quality improvement strategies, evaluations to understand success and failures in improving quality and safety, etc. A wide range of topics are covered, such as cancer care, management of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative disorders (dementia, Parkinson’s), asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), fertility disorders, health lifestyles (stop smoking, adherence to medication advice, exercises, alcohol use, etc.), safety issues (infections in hospitals, hand hygiene, pressure ulcers, triage safety, safety in primary care), organizational issues (integrated with chronic diseases, skill mix changes, etc.), and implementation programs (e.g., Breakthrough Series, accreditation, pay-for-performance models, consumer information).

For these projects (national and international) we collaborate closely with policy makers (e.g., departments of health), professional bodies of clinical professionals, health care plans/insurers, patient organizations, and specific QI institutes (similar to the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI)).

2. How do you/does your organization approach quality improvement research/evaluation? What research designs/methods are employed? What types of measures are needed for evaluation? Are the needed measures available? Is the infrastructure (e.g., information technology) able to support optimal research designs?

A wide variety of research methodologies are applied. A few years ago we composed a series of articles for British Medical Journal (BMJ) and Quality and Safety in Health Care for that purpose (Grol et al., 2002).

We composed a book of that set of papers, which was published by BMJ books in 2004 (now Blackwell Publishing). We use this book for educational purposes for our researchers and Ph.D. students.

Another book that is now widely used for both practitioners and researchers of quality improvement is Improving Patient Care: Implementation of Change in Clinical Practice (Grol et al., 2005). This comprehensive book on QI covers theory, evidence, and research methods on QI in health care and is now used in many countries

(Netherlands, Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom) in education on quality improvement (research). We aim to build all our research projects and Ph.D. theses on the theories and models presented in that book.

A variety of health services research (HSR) methods are used in the average QI project, such as systematic reviews, variation and determinant studies, analysis of routine data, clinimetrics and psychometrics (in the development and validation of indicators and instruments to measure quality and change), (cluster) randomized trials controlled before and after studies, observational methods (e.g., surveys, audits), qualitative methods (interviews, focus groups, observations), process evaluations of change processes, and economic evaluations.

The average Ph.D. thesis contains around 6–7 papers published in or submitted to international scientific journals, with different methods used, often ordered as:

-

Systematic review summarizing the state of knowledge in the field.

-

Development and validation of measures, indicators, and instruments to measure quality and change.

-

Assessment audit of actual care or services provided; analysis of determinants of variation.

-

Barrier analysis (obstacles/incentives to change).

-

QI study on effects of a specific strategy or change program (different designs).

-

Process evaluations to understand causes for success and failure in the process of change.

-

Economic evaluation of the costs involved in improving quality and safety.

We have a variety of continuous data collection infrastructures that can help us to undertake specific studies (e.g., on determinants of variation in care provision). Overall, we have very good infrastructures for this type of research both in terms of expertise (e.g., epidemiology, social sciences, education sciences, economic evaluation, management sciences), support staff (e.g., statisticians, research assistants), and information and communication technology (ICT).

We have experienced that you need critical mass and different types of expertise to perform QI research. More than 15 senior researchers are now involved in our program to supervise projects and Ph.D. students. Since most of the seniors have been trained as

Ph.D. students in our own center, they have the appropriate expertise for this type of research.

3. What quality improvement strategies have you identified as effective as a result of your research?

We would like to refer to our comprehensive handbook on QI. This shows that different strategies can be effective in different settings under specific conditions, such as small-group interactive education (local collaborative) works well for isolated care providers in primary care; outreach visits and adding a nurse to the primary care are effective in prevention in primary care; and computerized decision support, restructuring care processes, and multidisciplinary collaboration are often needed to start change in acute hospitals.

What we found in most of our projects was:

-

Organizational and structural measures often need to be taken and in place before change of professional decision making is possible.

-

Whether change interventions are successful depends largely on the general culture and attitude to change in a hospital, a ward, a practice, and professionals.

We need to do more research on these issues and on strategies to improve these aspects.

4. Do you think the type of evidence required for evaluating quality improvement interventions is fundamentally different from that required for interventions in clinical medicine?

a. If you think the type of evidence required for quality improvement differs from that in the rest of medicine, is it because you think quality improvement interventions intrinsically require less testing or that the need for action trumps the need for evidence?

b. Does this answer depend on variations in context (e.g., across patients, clinical microsystems, health plans, regions)? Other contextual factors? Which aspects of context, if any, do you measure as part of quality improvement research?

Quality improvement research is a specific field within HSR, and the type of evidence needed for good HSR is also needed for good QI research. In order to convince policy makers and practitioners, we need rigorous research methodologies. Rigorous research is not automatically similar to RCTs. What the best research design or method is depends on the research question. Currently there

are many research questions related to understanding successes and failures in quality improvement. Different theories need to be explored.

A variety of research methods, both qualitative and quantitative, can be helpful. In medicine there is a strong tradition to use methodologies from clinical epidemiology. To address complex issues related to change patient care successfully, approaches from other disciplines (e.g., sociology, psychology, anthropology, economics, management, education) may be crucial.

5. Do you have suggestions for appropriately matching research approaches to research questions?

Different steps in a quality improvement process (see our handbook Improving Patient Care) result in different research questions that demand different research methods (e.g., development and validation of measures to study actual quality or change in performance demand methods derived from psychometrics and clinimetrics: testing the value of a change program may demand a cluster RCT or controlled study).

6. What additional research is needed to help policy makers/ practitioners improve quality of care?

See forthcoming paper on building capacity of QI researchers.

SPREAD AND IMPLEMENTATION OF RESEARCH FINDINGS

Paul Wallace

Organizational Background

The Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program is a collaboration of three distinct legal business entities: the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan (KFHP), Kaiser Foundation Hospitals (KFH), and the Permanente Medical Groups (PMGs). The Permanente Federation is a national organization representing the collective interests of the PMGs. KFHP includes the insurance and financing activities; KFH owns large portions of the physical assets of the delivery system, including hospitals and clinics; and the PMGs are responsible for care delivery and overall medical management. KFHP and KFH are referred to collectively as Kaiser Foundation Health Plan and Hospitals (KFHP-H).

Key values of the KFHP-H and PMG partnership that are integral to the spread of innovations include:

-

Operations in multiple geographic regions as instances of a fully integrated delivery system.

-

Health Plan and Permanente Medical Group contractual mutual exclusivity.

-

Prepayment (global capitation).

Care Delivery and Strategy

The eight regionally based PMGs are organized, operated, and governed as autonomous, multispecialty group practices. Nationally, more than 12,000 physician providers participate in the PMG partnerships or professional corporations. The PMGs and Kaiser Health Plan and Hospitals collectively employ an additional 150,000 personnel. Each PMG has a medical services agreement with KFHP-H with delegated full responsibility for arranging and providing necessary medical care for members in their geographic region.

The PMGs and the Permanente Federation partner as equals with KFHP-H to govern the entire organization, develop strategy, and promote key initiatives.

Quality Oversight

Kaiser Permanente (KP) actively participates in national U.S. quality programs, including public accountability through the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), the National Quality Forum, and others.

The Federation, PMGs, and KFHP-H organizations include quality structures with shared accountability at both the regional and national levels to the highest levels of KP organizational governance. Overall quality or “Big Q” is viewed as a crosscutting and inclusive activity that includes clinical quality, safety, service, resource stewardship (utilization management), and risk management. An interregional KP National Quality Committee, including national and regional senior medical group and health plan and hospital leaders with accountability for quality (Big Q), meets regularly to review the ongoing program quality agenda and portfolio and to endorse and charter major national initiatives. For initiatives of the highest identified priority, additional endorsement will be sought from the Kaiser Permanente Program Group (KPPG), the penultimate organizational, operational governance group that includes the most senior Health Plan and Medical Group Leadership. A recent example of KPPG endorsement is a national effort to implement palliative care programs. An additional internal process, the Medical Director ’s

Quality Review, annually reviews key aspects of each region’s quality performance.

KP has created several national/interregional entities to oversee and support aspects of overall program quality. Examples include:

-

The Care Management Institute (CMI), with a focus on evidence-based medicine and population-based care programs, especially for the chronically ill. CMI supports defined networks of regionally based individuals involved in implementation and program evaluation and analysis. CMI is overseen by a Care Management Committee that itself is accountable to the KP National Quality Committee.

-

The KP Aging Network to oversee and promote care improvement and innovation for the more senior KP members.

-

The Care Experience Council, charged to identify and promote opportunities to improve overall service delivery and the Care Experience.

-

The National Product Council, to advise and promote use of evidence-based technologies and oversee appropriate stewardship of organizational resources in purchasing and procurement decisions.

Additional coordinated interregional efforts include pharmacy, transplants, new clinical technologies, diversity, and research. Finally, substantial coordinated resources are committed at the national and regional levels to support innovation and practice transfer in the use of the electronic medical record, KP HealthConnect.

Similar organizational structures and support capabilities are also often developed and sustained at the regional level, especially in the larger KP regions such as Northern and Southern California. Furthermore, in larger regions an additional layer of quality oversight and promotion will reside at the subregional (medical center) level. This document focuses primarily on interregional transfer and spread.

Formal Organizational Award Programs to Recognize and Promote Locally Developed Innovation

KP supports two major quality-related award and recognition programs to identify the most promising innovations evolving at the regional and subregional (medical center and clinic) level and to actively promote spread of those programs:

-

The James A. Vohs Award for Quality is presented annually for the project(s) that best represents an effort to improve quality through documented institutionalized changes in direct patient care, with potential for transfer to other locations. Recent examples include initiatives for hypertension control, breast cancer screening, and management of chronic pain.

-

The annual David M. Lawrence, MD, Patient Safety Award recognizes projects that advance the quality of care by improving the safety of care. The award’s goals are to (1) create a culture of safety, (2) develop and standardize successful patient safety measures in KP facilities, and (3) define and implement an innovative and transferable regional intervention in patient safety. Recent recipients include initiatives for rapid response teams, perinatal safety, and executive walk-arounds.

With both the Vohs and Lawrence awards, a major selection criterion is the potential for spread. Resources in the form of support for the award-winning team to travel and help promote their innovation in other regions are included in the awards.

1. How do you spread research findings or other quality improvement strategies within and outside of your organization?

Opportunities for spread can be modeled as two dominant channels:

-

Arising at the most local aspects of the delivery system (“bottom up”); and

-

From efforts of national quality-related groups adopting, importing, or developing de novo potential interventions (“top down”).

While most examples of spread will require a mix of both bottom-up and top-down efforts, the two models have complementary features.

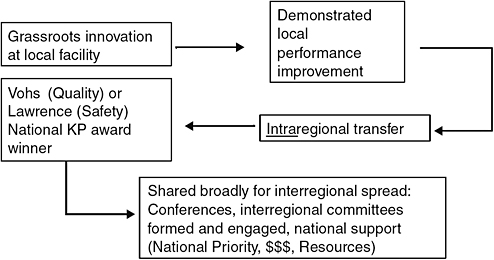

“Bottom up”:

Operational investigations in the clinical setting, including busy physician practices, are common. For example, a clinic in the North-west region was awarded a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation grant to study self-management among diabetic members, and the KP National Chronic Pain Workgroup has explicit goals for supporting regional plan-do-study-act projects in medication management,

FIGURE C-2 Channel A: bottom up.

utilization issues, and clinician-to-clinician communication. Spread of similar innovations occurs as in Figure C-2.

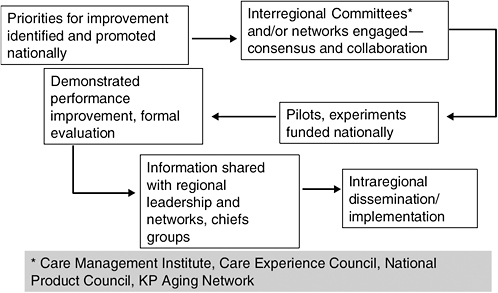

“Top down”:

National KP internal organizations such as the Care Management Institute and the Care Experience Council devote resources to ongoing “environmental scanning” within and external to KP to identify evolving and promising innovations for potential expanded implementation. Many of the areas of eventual focus have had their roots in the health services research activities of the regionally based KP Research Centers. The KP organization also has formal collaborations with multiple external improvement organizations, including the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making (Boston), and Medicaid-centered improvement work and collaboratives supported by the Center for Health Care Strategies (Princeton, NJ). Identified innovations can be spread as in Figure C-3.

Additional implementation supports are leveraged for both channels and include the following examples:

-

National meetings with either:

-

A crosscutting agenda, such as the Annual National Quality Conference attended by several hundred KP employees. The conference features all of the aspects of Big Q and highlights a few promising opportunities for adoption and spread.

-

FIGURE C-3 Channel B: top down.

-

An innovation-focused agenda, such as convening those working on palliative care program implementation.

-

Initiative-specific webinars, workshops, and in-person trainings.

-

Networks, formal (e.g., the CMI Implementation Network) and informal or created to support a specific initiative (e.g., a palliative care network).

-

The Permanente Journal, a KP National peer-reviewed quarterly journal sponsored by the Permanente Federation to communicate and promote aspects of practice within KP.

2a. How are the innovations you implement identified?

As noted above, quality-based innovations selected for broad organizational spread will generally be either the product of ongoing environmental scanning, assessment, and prioritization by a national or regionally based quality oversight and promotion group (e.g., the Care Experience Council or CMI) or reflect a “bottom-up” local effort that has achieved regional implementation, endorsement, and advocacy. Overall quality portfolio balance is supported and overseen by the national quality oversight structures and processes, including the KP National Quality Committee. The selection processes for the Lawrence and Vohs awards have similar interregional representation by senior leadership with accountability for quality performance.

2b. What types of evidence (e.g., clinical evidence, evidence on the innovation’s effectiveness, generalizability to your setting) are required before an innovation is chosen for implementation?

While each initiative will reflect a complex calculus of benefit balanced with cost and resource demand, key attributes that will foster support for broad adoption include:

-

Scientific credibility, including a strong evidence base generally qualifying for, if not yet having achieved, publication in a peer-reviewed journal:

-

Particular favorability will be given to work originally or primarily “done here” within KP either at the KP Research Centers and/or in a KP operational setting.

-

-

Operational credibility:

-

A strong business case reflecting return in the form of overall enhanced value for a significant portion of the KP membership, generally within a less than 2- to 3-year time frame.

-

Internal initiative leadership combining both subject expertise and ideally, familiarity and facility with overall national and regional operations.

-

Agreement on the team structure and roles and responsibilities.

-

A draft workplan.

-

A draft measurement plan that can ideally be achieved with existing capabilities and resources.

-

-

Demonstrated successful piloting followed by prior wide intraregional adoption and/or spread beyond the piloting site.

-

Identified executive sponsors at the regional and national levels willing to commit appropriate resources.

-

Consideration given to the degree to which an initiative complements and extends current efforts and capabilities, including leveraging existing network relationships that can be adapted to support spread versus the need to develop and sustain a new network.

An area of persistent internal controversy is the allowance and/or facilitation of local modification of an endorsed practice. Advocates of precise replication link full benefit realization with consistent and complete replication of the primary implementation of an intervention, while supporters of local modification cite improved local buy-in and accommodation of operational differences.

3. What methods are used to evaluate the success of implemented innovations?

Innovations and initiatives identified for broad spread will have a proactively agreed-upon evaluation plan, including spread milestones developed in conjunction with and shared regularly with the initiative’s executive sponsors at the national and regional levels. The KP National Quality Committee, and KPPG when involved, will provide regular oversight and monitoring from a national perspective. Similar accountabilities will be established within each operational site—either at a regional or sub-regional/medical center level.

The responsible national oversight group will ensure that networking resources such as an online community are formed to permit participants to share ideas, challenges, and solutions, in addition to letting people post key documents, tools, recent research, or articles or learn about upcoming webinars. While each innovation will to some degree be unique, key elements for evaluation will include:

-

Progress in local settings on forming the infrastructure for implementation, including appropriate local care delivery and analytic personnel resource assignment, and when necessary, funding and successful recruitment of new professional roles.

-

The establishment of local workplans and goals.

-

The creation and deployment of training events and resources such as online training modules.

-

Active communication about the initiative within the local setting to key stakeholders.

-

Development and production of an initiative-specific measurement dashboard to show progress via agreed-upon outcomes and process metrics.

-

Efforts, including successes and challenges, encountered in leveraging KP HealthConnect and other health information technologies to support the initiative.

In addition to initiative-specific evaluation, the portfolio of innovation and diffusion is periodically reviewed in total or in part at multiple levels of the organization, including KPPG, the KP National Quality Committee, entities like CMI and the Care Experience Council, and within regional governance and oversight structures. Crosscutting organizational goals for overall spread have been implemented, such as a recent accountability for CMI to support and document annually the spread between regions of at least 10 innovations related to chronic care management.

David Pryor

1. How do you spread research findings or other quality improvement strategies within and outside of your organization?

INTERNAL

-

By Intranet: We maintain a dedicated Intranet site that highlights all of our QI programs. This site provides information on program design as well as outcomes and provides resources for our internal partners.

-

We also present the results of our QI programs to our aligned business leads throughout the company through regularly scheduled meetings. In addition, we have committees, such as our Internal Advisory Committee on Racial and Ethnic Equality that meet to discuss QI initiatives in this specific area of interest.

-

Internal communication: We selectively use newsletters and e-mails to highlight QI programs. Our Clinical Connection newsletter is produced quarterly and is transmitted to the entire health care delivery team.

EXTERNAL

-

Association meetings: Aetna presents on the outcomes of our QI programs at industry conferences and events such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), the Disease Management Association of America, and America’s Health Insurance Plans Awards.

-

News media: We use print and online media to share the results of our QI programs.

-

Presentations to external customers such as the Aetna Client Advisory Group and Consultant Forums.

-

Materials mailed to members.

-

Physician tool kits supplied to Aetna network physicians.

-

Presentations to our Racial and Ethnic External Advisory Committee and solicitation of feedback and guidance as this committee is made up of subject matter experts in implementing interventions that address racial and ethnic disparities in health care.

2a. How are the innovations you implement identified?

-

Gaps identified from internal data analysis (e.g., HEDIS results, NCQA, provider surveys).

-

Gaps identified from external data analysis (e.g., disparities in breast cancer screening, health literacy).

-

Suggestions from internal and external constituents.

-

Surveillance of Medical Network Trend Operating Report (MENTOR).

2b. What types of evidence (e.g., clinical evidence, evidence on the innovation’s effectiveness, generalizability to your setting) are required before an innovation is chosen for implementation?

-

Membership impact and size.

-

Buy-in and support from customers (e.g., Aetna Client Advisory Group (ACAG), National Sales Consultants).

-

Feasibility of implementation.

3. What methods are used to evaluate the success of implemented innovations?

-

Clinical/quality improvement.

-

Improvement in satisfaction.

-

Cost improvement—return on investment.

-

Efficiency.

THE ROLE OF HISTORY

Guenter B. Risse

The theories and practices designed to improve quality of care demand changes in the conduct of health systems and their institutions. Most of the proposed changes represent alterations, adjustments, translations, even transformations, and replacements of current activities and technologies. This quest for improvement implies that current outcomes are unsatisfactory, occasionally harmful. Such assessments derive from retrospective studies gauging the outcome of previous decisions and procedures. Thus, it can be argued that the basis for health care quality improvement is historical: understanding the processes of change, how it occurs, and how it can be prompted.

History is the ultimate outcome study. As a basic social science, its methodology is central in collecting, organizing, and interpreting past events. In the area of health care, historical perspectives provide valuable insights into the construction and communication of medical knowledge with its empowering qualities for professionalization and education.

Understanding the nexus between professional action and identity in contingent, changing institutional settings can only be understood by examining the roots of medical development and behavior.

Here the historical study of ritualism in health care constitutes a useful framing device to uncover particular values, belief systems, and relationships that are currently characterized as barriers to greater institutional efficiency and quality of care (Risse, unpublished).

In the United States, we are confronted with a highly decentralized, private health care system shaped more than a century ago. Since each institution functions within its own ecological niche determined by sponsorship and geography, cultural matrix and organizational schemes, professional relationships and technological capacities, case studies constitute a valuable source for understanding institutional identity as well as some of the paths and barriers to transformation and improvement (Risse, 1999). Employing a historical-ethnographic approach may capture some of the complexity inherent in quality improvement, promising valuable insights instead of full-fledged blueprints. The often-cited example of changes at the Allegheny General Hospital could be the target of such a probe. Historians, anthropologists, sociologists, and behavioral scientists should be recruited to interview all protagonists (health care personnel and patients), examine pertinent written and electronic records, determine organizational flow charts, and unpack and analyze decision making and its consequences. The final story will bring into consciousness a textured, organized narrative that may well provide valuable lessons for understanding the contours of change and the often-admirable ability of human beings to negotiate and adapt to it. In other occasions, historians and other social scientists became embedded in health care institutions, witnessing events and composing valuable diaries of their experiences (Fox, 1959).

Finally and perhaps most importantly, history is also a discipline within the humanities. It functions as our collective identity, revealing human nature and evolution. The 1970s transformed medicine into a “health care delivery service,” solidly placed in the business world, something to be competitively offered and sold like other commodities. Linked through insurance contracts, physicians became known as “providers” and patients were transformed into “recipients” or “consumers,” creating the current era of “retail health care.” While health care delivery systems have benefited enormously from their inclusion into corporate structures and provision of managerial expertise, I disagree with the notion that health care now constitutes merely “repair work,” provided within a customer–supplier relationship. The prevalent materialism in biomedicine neglects the human spirit. Since the dawn of humankind, health care has operated within a highly emotionally charged

context, with matters of life, pain and disability, identity, and social status all at stake. Negotiating today’s medical marketplace can be daunting. Suffering individuals, by the very nature of patienthood, will always remain in a vulnerable, emotional, and dependent condition. Mending bodies without reference to the mind creates a false dichotomy and forces patients to make hard choices. In the future, patients will still require both well-managed and technically proficient health care systems as well as empathetic human contacts. Both are necessary for building relationships that will terminate their emotional isolation while generating understanding, reassurance, and hope. Many find their true healing elsewhere, away from medical management. Seen from a historical perspective, the very notion of health care quality improvement must address the human condition. Better outcomes and true patient satisfaction depend on it. Whether our competitive commercial society and corporate, business-oriented medicine can comply with such essential human needs remains an open question.

REFERENCES

Aiken, L. H., S. P. Clarke, D. M. Sloane, J. Sochalski, and J. H. Silber. 2002. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. Journal of the American Medical Association 288(16):1987-1993.

Ash, J. S., D. F. Sittig, E. G. Poon, K. Guappone, E. Campbell, and R. H. Dykstra. 2007. The extent and importance of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 14(4):415-423.

Auerbach, A. D., C. S. Landefeld, and K. G. Shojania. 2007. The tension between needing to improve care and knowing how to do it. New England Journal of Medicine 357(6):608-613.

Brennan, T. A., A. Gawande, E. Thomas, and D. Studdert. 2005. Accidental deaths, saved lives, and improved quality. New England Journal of Medicine 353(13):1405-1409.

Campbell, E. M., D. F. Sittig, J. S. Ash, K. P. Guappone, and R. H. Dykstra. 2006. Types of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 13(5):547-556.

Forster, A. J., J. Andrade, and C. van Walraven. 2005. Validation of a discharge summary term search method to detect adverse events. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 12(2):200-206.

Forster, A. J., I. Fung, S. Caughey, L. Oppenheimer, C. Beach, K. G. Shojania, and C. van Walraven. 2006. Adverse events detected by clinical surveillance on an obstetric service. Obstetrics and Gynecology Journal 108(5):1073-1083.

Fox, R. C. 1959. Experiment perilous: Physicians and patients facing the unknown. Glencoe, IL: The Free Press.

Grol, R., R. Baker, and F. Moss. 2002. Quality improvement research: Understanding the science of change in health care. Quality and Safety in Health Care 11(2): 110-111.

Grol, R., M. Wensing, and M. P. Eccles. 2005. Improving patient care: The implementation of change in clinical practice. Oxford, U.K.: Elsevier Health Sciences.

Kaboli, P. J., A. B. Hoth, B. J. McClimon, and J. L. Schnipper. 2006. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: A systematic review. Archives of Internal Medicine 166(9):955-964.

Koppel, R., J. P. Metlay, A. Cohen, B. Abaluck, A. R. Localio, S. E. Kimmel, and B. L. Strom. 2005. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. Journal of the American Medical Association 293(10):1197-1203.

Kucukarslan, S. N., M. Peters, M. Mlynarek, and D. A. Nafziger. 2003. Pharmacists on rounding teams reduce preventable adverse drug events in hospital general medicine units. Archives of Internal Medicine 163(17):2014-2018.

Leape, L. L., D. J. Cullen, M. D. Clapp, E. Burdick, H. J. Demonaco, J. I. Erickson, and D. W. Bates. 1999. Pharmacist participation on physician rounds and adverse drug events in the intensive care unit. Journal of the American Medical Association 282(3):267-270.

Leape, L. L., D. M. Berwick, and D. W. Bates. 2002. What practices will most improve safety? Evidence-based medicine meets patient safety. Journal of the American Medical Association 288(4):501-507.

Mason, J., N. Freemantle, I. Nazareth, M. Eccles, A. Haines, and M. Drummond. 2001. When is it cost-effective to change the behavior of health professionals? Journal of the American Medical Association 286(23):2988-2992.

Needleman, J., P. Buerhaus, S. Mattke, M. Stewart, and K. Zelevinsky. 2002. Nurse-staffing levels and the quality of care in hospitals. New England Journal of Medicine 346(22):1715-1722.

Nuckols, T. K., and J. J. Escarce. 2005. Residency work-hours reform. A cost analysis including preventable adverse events. Journal of General Internal Medicine 20(10):873-878.

Patterson, E. S., R. I. Cook, and M. L. Render. 2002. Improving patient safety by identifying side effects from introducing bar coding in medication administration. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 9(5):540-553.

Risse, G. B. 1999. Mending bodies, saving souls: A history of hospitals. New York: Oxford University Press.

Risse, G. B. (unpublished). The hospital as house of rituals.

Scriven, M. 1991. Evaluation thesaurus. Fourth ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publishers, Inc.

Shojania, K. G. 2002. Safe but sound: Patient safety meets evidence-based medicine. Journal of the American Medical Association 288(4):508-513.

Shojania, K. G., and J. M. Grimshaw. 2005. Evidence-based quality improvement: The state of the science. Health Affairs (Millwood) 24(1):138-150.

Shojania, K. G., B. W. Duncan, K. M. McDonald, and R. M. Wachter. 2001. Making health care safer: A critical analysis of patient safety practices. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Shojania, K. G., E. C. Burton, K. M. McDonald, and L. Goldman. 2003. Changes in rates of autopsy-detected diagnostic errors over time: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association 289(21):2849-2856.

Shojania, K. G., K. M. McDonald, R. M. Wachter, and D. K. Owens. 2004. Closing the quality gap: A critical analysis of quality improvement strategies. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Shojania, K. G., S. R. Ranji, K. M. McDonald, J. M. Grimshaw, V. Sundaram, R. J. Rushakoff, and D. K. Owens. 2006a. Effects of quality improvement strategies for type 2 diabetes on glycemic control: A meta-regression analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association 296(4):427-440.

Shojania, K. G., K. E. Fletcher, and S. Saint. 2006b. Graduate medical education and patient safety: A busy—and occasionally hazardous—intersection. Annals of Internal Medicine 145(8):592-598.

Stelfox, H. T., D. W. Bates, and D. A. Redelmeier. 2003. Safety of patients isolated for infection control. Journal of the American Medical Association 290(14):1899-1905.

Walsh, J. M., K. M. McDonald, K. G. Shojania, V. Sundaram, S. Nayak, R. Lewis, D. K. Owens, and M. K. Goldstein. 2006. Quality improvement strategies for hypertension management: A systematic review. Medical Care 44(7):646-657.

Wennberg, J., and A. Gittelsohn. 1973. Small area variations in health care delivery. Science 182(117):1102-1108.

Wennberg, J., and A. Gittelsohn. 1982. Variations in medical care among small areas. Scientific American 246(4):120-134.