Summary

ABSTRACT

Cancer care today often provides state-of-the-science biomedical treatment, but fails to address the psychological and social (psychosocial) problems associated with the illness. This failure can compromise the effectiveness of health care and thereby adversely affect the health of cancer patients. Psychological and social problems created or exacerbated by cancer—including depression and other emotional problems; lack of information or skills needed to manage the illness; lack of transportation or other resources; and disruptions in work, school, and family life—cause additional suffering, weaken adherence to prescribed treatments, and threaten patients’ return to health.

A range of services is available to help patients and their families manage the psychosocial aspects of cancer. Indeed, these services collectively have been described as constituting a “wealth of cancer-related community support services.”

Today, it is not possible to deliver good-quality cancer care without using existing approaches, tools, and resources to address patients’ psychosocial health needs. All patients with cancer and their families should expect and receive cancer care that ensures the provision of appropriate psychosocial health services. This report recommends ten actions that oncology providers, health policy makers, educators, health insurers, health plans, quality oversight organizations, researchers and research sponsors, and consumer advocates should undertake to ensure that this standard is met.

PSYCHOSOCIAL PROBLEMS AND HEALTH

The burden of illnesses and disabilities in the United States and the world is closely related to social, psychological, and behavioral aspects of the way of life of the population. (IOM, 1982:49–50)

Health and disease are determined by dynamic interactions among biological, psychological, behavioral, and social factors. (IOM, 2001:16)

Because health … is a function of psychological and social variables, many events or interventions traditionally considered irrelevant actually are quite important for the health status of individuals and populations. (IOM, 2001:27)

In previous reports the Institute of Medicine (IOM) has issued strong findings about the important role of psychological/behavioral and social factors in health and recommended more attention to these factors in the design and delivery of health care (IOM, 1982, 2001, 2006). In 2005, the IOM was asked once again to examine the contributions of these psychosocial factors to health and how best to address them—in this case in the context of cancer, which encompasses some of the nation’s most serious and burdensome illnesses.

STUDY CONTEXT

The Reach and Influence of Cancer

One in ten American households today has a family member who has been diagnosed with or treated for cancer1 within the past 5 years (USA Today et al., 2006), and 41 percent of Americans can expect to be diagnosed with cancer at some point in their lifetime (Ries et al., 2007). More than ten and a half million people in the United States live with a past or current diagnosis of cancer (Ries et al., 2007).

Early detection and improved treatments for many different types of cancer have changed our understanding of this group of illnesses from that of a single disease that was often uniformly fatal in a matter of weeks or months to that of a variety of diseases—some of which are curable, all of which are treatable, and for many of which long-term disease-free survival is possible. In the past two decades, the 5-year survival rate for the 15 most common cancers has increased from 43 to 64 percent for men and from 57 to 64 percent for women (Jemal et al., 2004).

Nonetheless, the diseases that make up cancer represent both acute life-threatening illnesses and serious chronic conditions. Their treatment is

typically very challenging physically to patients, requiring some combination of surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy for months or years. Even when treatment has been completed and no cancer remains, the frequently permanent, serious residua of cancer and/or the side effects of chemotherapy, radiation, hormone therapy, surgery, and other treatments can permanently impair cardiac, neurological, kidney, lung, and other body functioning, necessitating ongoing monitoring of cancer survivors’ health and many adjustments in their daily living. Eleven percent of adults with cancer or a history of cancer (almost half of whom are age 65 or older) report having one or more limitations in their ability to perform activities of daily living such as bathing, eating, or using the bathroom, and 58 percent report other functional disabilities, such as the inability to walk a quarter of a mile, or to stand or sit for 2 hours (Hewitt et al., 2003). Long-term survivors of childhood cancer are at particularly elevated risk compared with others their age. Nearly 20 percent of those who survive 5 years or more report limitations in activities such as carrying groceries, climbing a flight of stairs, or walking a block (Ness et al., 2005). Significant numbers of individuals stop working or experience a change in employment after being diagnosed or treated for cancer (IOM and NRC, 2006).

Not surprisingly, significant mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety disorders, are common in patients with cancer (Spiegel and Giese-Davis, 2003; Carlsen et al., 2005; Hegel et al., 2006). Studies have also documented the presence of symptoms meeting the criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in adults and children with cancer, as well as in the parents of children diagnosed with cancer (Kangas et al., 2002; Bruce, 2006).2 These mental health problems are additional contributors to functional impairment in carrying out family, work, and other societal roles; poor adherence to medical treatments; and adverse medical outcomes (Katon, 2003).

Patients with cancer (like those with other chronic illnesses) identify a number of other problems that adversely affect their health care and recovery, including poor communication with physicians, lack of knowledge about their illness and its management, lack of transportation to health care appointments, financial problems, and lack of health insurance (Wdowik et al., 1997; Eakin and Strycker, 2001; Riegel and Carlson, 2002; Bayliss et al., 2003; Boberg et al., 2003; Skalla et al., 2004; Jerant et al., 2005; Mallinger et al., 2005). Fifteen percent of households affected by cancer report having left a doctor’s office without getting answers to important

questions about the illness (USA Today et al., 2006). The American Cancer Society and CancerCare report receiving more than 100,000 requests annually for transportation so patients can get to medical appointments, pick up medications, or receive other health services. In 2003, nearly one in five (12.3 million) people with chronic conditions3 lived in families that had problems paying medical bills (May and Cunningham, 2004; Tu, 2004). Among uninsured cancer survivors, more than one in four delayed or decided not to get treatment because of its cost, and 41 percent were unable to pay for basic necessities, including food (USA Today et al., 2006). About 5 percent of the 1.5 million American families who filed for bankruptcy in 2001 reported that medical costs associated with cancer contributed to their financial problems (Himmelstein et al., 2005).

Although family and loved ones often provide substantial amounts of emotional and logistical support and hands-on personal and nursing care (valued at more than $1 billion annually) in an effort to address these needs (Hayman et al., 2001; Kotkamp-Mothes et al., 2005), they often do so at great personal cost, themselves experiencing depression, other adverse health effects, and an increased risk of premature death (Schultz and Beach, 1999; Kurtz et al., 2004). Caregivers providing support to a spouse who report strain from doing so are 63 percent more likely to die within 4 years than others their age (Schultz and Beach, 1999). The emotional distress of caregivers also can directly affect patients. Studies of partners of women with breast cancer (predominantly husbands, but also “significant others,” daughters, friends, and others) find that partners’ mental health correlates positively with the anxiety, depression, fatigue, and symptom distress of women with breast cancer and that the effects are bidirectional (Segrin et al., 2005, 2007).

Effects of Psychosocial Problems on Physical Health

The psychosocial problems described above can adversely affect health and health care in many ways. For example, a substantial literature has documented low income as a strong risk factor for disability, illness, and death (IOM, 2001; Subramanian et al., 2002). Inadequate income limits one’s ability to purchase food, medications, and health care supplies necessary for health and health care, as well as to secure necessary transportation and obtain relief from other stressors that can accompany tasks of everyday life (Kelly et al., 2006). As noted above, lack of transportation to medical appointments, the pharmacy, the grocery store, health education classes, peer support meetings, and other out-of-home health resources is common,

and it can pose a barrier to health monitoring, illness management, and health promotion.

Depressed or anxious individuals have lower social functioning, more disability, and greater overall functional impairment than those without these conditions (Spitzer et al., 1995; Katon, 2003). Distressed emotional states also often generate additional somatic problems, such as sleep difficulties, fatigue, and pain (Spitzer et al., 1995; APA, 2000), which can confound the diagnosis and treatment of physical symptoms. Patients with major depression as compared with nondepressed persons also have higher rates of unhealthy behaviors such as smoking, a sedentary lifestyle, and overeating. Moreover, depression and other adverse psychological states thwart behavior change and adherence to treatment regimens by impairing cognition, weakening motivation, and decreasing coping abilities. Evidence emerging from the science of psychoneuroimmunology—the study of the interactions among behavior, the brain, and the body’s immune system—is beginning to show how psychosocial stressors interfere with the working of the body’s neuro-endocrine, immune, and other systems.

In sum, people diagnosed with cancer and their families must not only live with and manage the challenges and risks posed to their physical health, but also overcome psychosocial obstacles that can interfere with their health care and diminish their health and functioning. Unfortunately, the current medical system deploys its resources largely to address the former problems and often ignores the latter. As a result, patients’ psychosocial needs frequently remain unacknowledged and unaddressed in cancer care.

Cancer Care Is Often Incomplete

Many people living with cancer report that their psychosocial health care needs are not well addressed in their care. At the most fundamental level, throughout diagnosis, treatment, and post-treatment, patients report dissatisfaction with the amount and type of information they are given about their diagnosis, their prognosis, available treatments, and ways to manage their illness and health. Health care providers often fail to communicate this information effectively, in ways that are understandable to and enable action by patients (Epstein and Street, 2007). Moreover, individuals diagnosed with cancer often report that their care providers do not understand their psychosocial needs; do not consider psychosocial support an integral part of their care; are unaware of psychosocial health care resources; and fail to recognize, adequately treat, or offer referral for depression or other sequelae of stress due to the illness in patients and their families (President’s Cancer Panel, 2004; Maly et al., 2005; IOM, 2007). Twenty-eight percent of respondents to the National Survey of U.S. Households Affected by Cancer reported that they did not have a doctor who

paid attention to factors beyond their direct medical care, such as sources of support for dealing with the illness (USA Today et al., 2006). A number of studies also have shown that physicians substantially underestimate oncology patients’ psychosocial distress (Fallowfield et al., 2001; Keller et al., 2004; Merckaert et al., 2005). Indeed, oncologists themselves report frequent failure to attend to the psychosocial needs of their patients. In a national survey of members of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, a third of respondents reported that they did not routinely screen their patients for distress. Of the 65 percent that did do so, methods used were often untested or unreliable. In a survey of members of an alliance of 20 of the world’s leading cancer centers, only 8 reported screening for distress in at least some of their patients, and only 3 routinely screened all of their patients for psychosocial health needs (Jacobsen and Ransom, 2007).

A number of factors can interfere with clinicians’ addressing psychosocial health needs. These include the way in which clinical practices are designed, the education and training of the health care workforce, shortages and maldistribution of health personnel, and the nature of the payment and policy environment in which health care is delivered. Because of this, improving the delivery of psychosocial health services requires a multipronged approach.

STUDY SCOPE

In this context, the National Institutes of Health asked the IOM to empanel a committee to conduct a study of the delivery of the diverse psychosocial services needed by cancer patients and their families in community settings. The committee was tasked with producing a report describing barriers to access to psychosocial services and ways in which these services can best be provided, analyzing the capacity of the current mental health and cancer treatment system to deliver such care, delineating the associated resource and training requirements, and offering recommendations and an action plan for overcoming the identified barriers. The committee interpreted “community care” to refer to all sites of cancer care except inpatient settings.

This study builds on and complements several prior reports on cancer care. First, two recent reports address quality of care for cancer survivors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition (IOM and NRC, 2006) well articulates how high-quality care (including psychosocial health care) should be delivered after patients complete their cancer treatment. Childhood Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life (IOM and NRC, 2003) similarly addresses survivorship for childhood cancer. The recommendations made in the present report complement and can be implemented consistent with the vision and recommendations put forth in those reports. Second, two other recent reports address palliative care:

Improving Palliative Care for Cancer (IOM and NRC, 2001) and When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families (IOM, 2003). For this reason, the additional considerations involved in providing end-of-life care are not addressed in this report.

FINDINGS GIVE REASON FOR HOPE

In carrying out its charge, the IOM Committee on Psychosocial Services to Cancer Patients/Families in a Community Setting found multiple reasons to be optimistic that improvements in the psychosocial health care provided to oncology patients and their families can be quickly achieved. First, there is good evidence of the effectiveness of a variety of services in relieving the emotional distress—even the debilitating depression and anxiety—experienced by cancer patients. Strong evidence also supports the utility of services aimed at helping individuals adopt behaviors that can minimize disease symptoms and improve overall health. Other psychosocial services, such as transportation to health care or financial assistance to purchase medications or supplies, while not the subject of effectiveness research, have long-standing and wide acceptance as humane approaches to addressing health-related needs. Such services are available through many health and human service providers. In particular, the strong leadership of organizations in the voluntary sector has created a broad array of psychosocial support services, in some cases available at no cost to the consumer. Together, these resources have been described as constituting a “wealth of cancer-related community support services” (IOM and NRC, 2006:229).

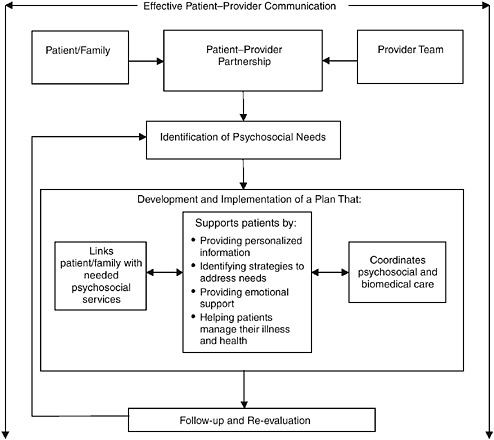

However, it is not sufficient simply to have effective services; interventions to identify patients with psychosocial health needs and to link them to appropriate services are needed as well. Fortunately, many providers of health services—some in oncology, some delivering health care for other complex health conditions—understand that psychosocial problems can affect health adversely and have developed interventions to address these problems. Some of these interventions are derived from theoretical or conceptual frameworks, some are based on research findings, and some have undergone empirical testing on their own; the best have all three sources of support. Common components of these interventions point to a model for the effective delivery of psychosocial health services (see Figure S-1). This model includes processes that (1) identify psychosocial health needs, (2) link patients and families to needed psychosocial services, (3) support patients and families in managing the illness, (4) coordinate psychosocial and biomedical health care, and (5) follow up on care delivery to monitor the effectiveness of services and make modifications if needed—all of which are facilitated by effective patient–provider communication. Routine implementation of many of these processes is currently under way by a number of exemplary cancer care providers in a variety of settings, attest-

FIGURE S-1 Model for the delivery of psychosocial health services.

ing to their feasibility in settings with varying levels of resources. However, many patients do not have the benefit of these interventions, and more active steps are needed if this lack of access is to become the exception rather than the rule.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on its findings with regard to the significant impact of psychosocial problems on health and health care, the existence of effective psychosocial services to address these problems, and the development and testing of strategies for delivering these services effectively, the committee concludes that:

Attending to psychosocial needs should be an integral part of quality cancer care. All components of the health care system that are involved in cancer care should explicitly incorporate attention to psychosocial needs

into their policies, practices, and standards addressing clinical health care. These policies, practices, and standards should be aimed at ensuring the provision of psychosocial health services to all patients who need them.

The committee defines psychosocial health services as follows:

Psychosocial health services are psychological and social services and interventions that enable patients, their families, and health care providers to optimize biomedical health care and to manage the psychological/behavioral and social aspects of illness and its consequences so as to promote better health.

This definition encompasses both psychosocial services (i.e., activities or tangible goods directly received by and benefiting the patient or family) and psychosocial interventions (activities that enable the provision of the service, such as needs assessment, referral, or care coordination). Examples of psychosocial needs and services that can address those needs are listed in Table S-1. Psychosocial interventions necessary for their appropriate provision are portrayed in Figure S-1. The committee offers the following recommendations for making attention to psychosocial health needs an integral part of quality cancer care.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ACTION

Recommendation 1: The standard of care. All parties establishing or using standards for the quality of cancer care should adopt the following as a standard:

All cancer care should ensure the provision of appropriate psychosocial health services by

-

facilitating effective communication between patients and care providers;4

-

identifying each patient’s psychosocial health needs;

-

designing and implementing a plan that

-

links the patient with needed psychosocial services,

-

coordinates biomedical and psychosocial care,

-

engages and supports patients in managing their illness and health; and

-

-

systematically following up on, reevaluating, and adjusting plans.

TABLE S-1 Psychosocial Needs and Formala Services to Address Them

Key participants and leaders in cancer care have major roles to play in promoting and facilitating adherence to this standard of care. Their respective roles are described in the following nine recommendations.

Recommendation 2: Health care providers. All cancer care providers should ensure that every cancer patient within their practice receives

care that meets the standard for psychosocial health care. The National Cancer Institute should help cancer care providers implement the standard of care by maintaining an up-to-date directory of psychosocial services available at no cost to individuals/families with cancer.

The committee believes that all providers can and should implement the above recommendation. Individual clinical practices vary by their patient population, their setting, and available resources in their clinical practice and community. Because of this, how individual health care practices implement the standard of care and the level at which it is done may vary. Nevertheless, as this report describes, the committee believes that it is possible for all providers to meet this standard in some way. This report identifies tools and techniques already in use by leading oncology providers to do so. There are many actions that can be taken now to identify and deliver needed psychosocial health services, even as the health care system works to improve their quantity and effectiveness. The committee believes that the inability to solve all psychosocial problems permanently should not preclude attempts to remedy as many as possible—a stance akin to oncologists’ commitment to treating cancer even when the successful outcome of every treatment is not assured. Patient education and advocacy organizations can play a key role in bringing this about.

Recommendation 3: Patient and family education. Patient education and advocacy organizations should educate patients with cancer and their family caregivers to expect, and request when necessary, cancer care that meets the standard for psychosocial care. These organizations should also continue their work on strengthening the patient side of the patient–provider partnership. The goals should be to enable patients to participate actively in their care by providing tools and training in how to obtain information, make decisions, solve problems, and communicate more effectively with their health care providers.

A large-scale demonstration of the implementation of the standard of care at various sites would provide useful information about how to achieve its implementation more efficiently; reveal approaches to implementation in both resource-rich and non-resource-rich environments; document approaches for successful implementation among vulnerable groups, such as those with low socioeconomic status, ethnic minorities, those with low health literacy, and the socially isolated; and identify different models for reimbursement. A demonstration could also be used to examine how various types of personnel can be used to perform specific interventions encompassed by the standard and how those personnel can best be trained.

Recommendation 4: Support for dissemination and uptake. The National Cancer Institute, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) should, individually or collectively, conduct a large-scale demonstration and evaluation of various approaches to the efficient provision of psychosocial health care in accordance with the standard of care. This program should demonstrate how the standard can be implemented in different settings, with different populations, and with varying personnel and organizational arrangements.

Because policies set by public and private purchasers, oversight bodies, and other health care leaders shape how health care is accessed, what services are delivered, and the manner in which they are delivered, group purchasers of health care coverage and health plans should take a number of actions to support the interventions necessary to deliver effective psychosocial health services. The National Cancer Institute, CMS, and AHRQ also should spearhead the development and use of performance measures to improve the delivery of these services.

Recommendation 5: Support from payers. Group purchasers of health care coverage and health plans should fully support the evidence-based interventions necessary to deliver effective psychosocial health services:

-

Group purchasers should include provisions in their contracts and agreements with health plans that ensure coverage and reimbursement of mechanisms for identifying the psychosocial needs of cancer patients, linking patients with appropriate providers who can meet those needs, and coordinating psychosocial services with patients’ biomedical care.

-

Group purchasers should review cost-sharing provisions that affect mental health services and revise those that impede cancer patients’ access to such services.

-

Group purchasers and health plans should ensure that their coverage policies do not impede cancer patients’ access to providers with expertise in the treatment of mental health conditions in individuals undergoing complex medical regimens such as those used to treat cancer. Health plans whose networks lack this expertise should reimburse for mental health services provided by out-of-network practitioners with this expertise who meet the plan’s quality and other standards (at rates paid to similar providers within the plan’s network).

-

Group purchasers and health plans should include incentives for the effective delivery of psychosocial care in payment reform programs—such as pay-for-performance and pay-for-reporting initiatives—in which they participate.

With respect to the above recommendation, “group purchasers” include purchasers in the public sector (e.g., Medicare and Medicaid) as well as group purchasers in the private sector (e.g., employer purchasers). Mental health care providers “with expertise in the treatment of mental health conditions in individuals undergoing complex medical regimens such as those used to treat cancer” include mental health providers who possess this expertise through formal education (such as specialists in psychosomatic medicine), as well as mental health care providers who have gained expertise though their clinical experiences, such as mental health clinicians collocated with and part of an interdisciplinary oncology practice.

Recommendation 6: Quality oversight. The National Cancer Institute, CMS, and AHRQ should fund research focused on the development of performance measures for psychosocial cancer care. Organizations setting standards for cancer care (e.g., National Comprehensive Cancer Network, American Society of Clinical Oncology, American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer, Oncology Nursing Society, American Psychosocial Oncology Society) and other standards-setting organizations (e.g., National Quality Forum, National Committee for Quality Assurance, URAC, Joint Commission) should

-

Create oversight mechanisms that can be used to measure and report on the quality of ambulatory oncology care (including psychosocial health care).

-

Incorporate requirements for identifying and responding to psychosocial health care needs into their protocols, policies, and standards.

-

Develop and use performance measures for psychosocial health care in their quality oversight activities.

Ultimately, the delivery of cancer care that addresses psychosocial needs depends on having a health care workforce with the attitudes, knowledge, and skills needed to deliver such care. Thus, professional education and training should not be ignored as a factor influencing health practitioners’ practices. The committee further recommends

Recommendation 7: Workforce competencies.

-

Educational accrediting organizations, licensing bodies, and professional societies should examine their standards and licensing and certification criteria with an eye to identifying competencies in delivering psychosocial health care and developing them as fully as possible in accordance with a model that integrates biomedical and psychosocial care.

-

Congress and federal agencies should support and fund the establishment of a Workforce Development Collaborative on Psychosocial Care during Chronic Medical Illness. This cross-specialty, multidisciplinary group should comprise educators, consumer and family advocates, and providers of psychosocial and biomedical health services and be charged with

-

identifying, refining, and broadly disseminating to health care educators information about workforce competencies, models, and preservice curricula relevant to providing psychosocial services to persons with chronic medical illnesses and their families;

-

adapting curricula for continuing education of the existing workforce using efficient workplace-based learning approaches;

-

drafting and implementing a plan for developing the skills of faculty and other trainers in teaching psychosocial health care using evidence-based teaching strategies; and

-

strengthening the emphasis on psychosocial health care in educational accreditation standards and professional licensing and certification exams by recommending revisions to the relevant oversight organizations.

-

-

Organizations providing research funding should support assessment of the implementation in education, training, and clinical practice of the workforce competencies necessary to provide psychosocial care and their impact on achieving the standard for such care set forth in recommendation 1.

In addition, improving the delivery of psychosocial health services requires targeted research. This research should aim to clarify the efficacy and effectiveness of new and existing services and to identify ways of improving the delivery of these services to various populations in different geographic locations and with varying levels of resources. Doing so would be facilitated by clarifying and standardizing the often unclear and inconsistent language used to refer to psychosocial services.

Recommendation 8: Standardized nomenclature. To facilitate research on and quality measurement of psychosocial interventions, the

National Institutes of Health (NIH) and AHRQ should create and lead an initiative to develop a standardized, transdisciplinary taxonomy and nomenclature for psychosocial health services. This initiative should aim to incorporate this taxonomy and nomenclature into such databases as the National Library of Medicine’s Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), PsycINFO, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), and EMBASE.

Recommendation 9: Research priorities. Organizations sponsoring research in oncology care should include the following areas among their funding priorities:

-

Further development of reliable, valid, and efficient tools and strategies for use by clinical practices to ensure that all patients with cancer receive care that meets the standard of psychosocial care set forth in recommendation 1. These tools and strategies should include

-

approaches for improving patient–provider communication and providing decision support to cancer patients;

-

screening instruments that can be used to identify individuals with any of a comprehensive array of psychosocial health problems;

-

needs assessment instruments to assist in planning psychosocial services;

-

illness and wellness management interventions; and

-

approaches for effectively linking patients with services and coordinating care.

-

-

Identification of more effective psychosocial services to treat mental health problems and to assist patients in adopting and maintaining healthy behaviors, such as smoking cessation, exercise, and dietary change. This effort should include

-

identifying populations for whom specific psychosocial services are most effective, and psychosocial services most effective for specific populations; and

-

development of standard outcome measures for assessing the effectiveness of these services.

-

-

Creation and testing of reimbursement arrangements that will promote psychosocial care and reward its best performance.

Research on the use of these tools, strategies, and services should also focus on how best to ensure delivery of appropriate psychosocial services to vulnerable populations, such as those with low literacy, older adults, the socially isolated, and members of cultural minorities.

Finally, the scope of work for this study included making recommendations for how to evaluate the impact of this report. The committee believes evaluation activities would be useful in promoting action on the preceding recommendations, and makes the following recommendation to that end.

Recommendation 10. Promoting uptake and monitoring progress. The National Cancer Institute/NIH should monitor progress toward improved delivery of psychosocial services in cancer care and report its findings on at least a biannual basis to oncology providers, consumer organizations, group purchasers and health plans, quality oversight organizations, and other stakeholders. These findings could be used to inform an evaluation of the impact of this report and each of its recommendations. Monitoring activities should make maximal use of existing data collection tools and activities.

Following are examples of the approaches that could be used for these monitoring efforts.

To determine the extent to which patients with cancer receive psychosocial services consistent with the standard of care and its implementation as set forth in recommendations 1 and 2, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) could

-

Conduct an annual, patient-level, process-of-care evaluation using a national sample and validated, reliable instruments, such as the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) instruments.

-

Add measures of the quality of psychosocial health care for patients (and families as feasible) to existing surveys, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and CAHPS.

-

Conduct annual practice surveys to determine compliance with the standard of care.

-

Monitor and document the emergence of performance reward initiatives (e.g., content on psychosocial care in requests for proposals [RFPs] and pay-for-performance initiatives that specifically include incentives for psychosocial care).

For recommendation 3 on patient and family education, DHHS could

-

Routinely query patient education and advocacy organizations about their efforts to educate patients with cancer and their family caregivers about what to expect from, and how to request when

-

necessary, oncology care that meets the standard of care set forth in recommendation 1.

-

In surveys conducted to assess the extent to which oncology care meets the standard of care, include questions to patients and caregivers about their knowledge of how oncology providers should address their psychosocial needs (the standard of care) and their actual experiences with receiving such care.

-

Use an annual patient-level process-of-care evaluation (such as CAHPS) to identify patient education experiences.

For recommendation 4 on dissemination and uptake of the standard of care, DHHS could report on the extent to which the National Cancer Institute/CMS/AHRQ had conducted demonstration projects and how they had disseminated the findings from those demonstrations.

For recommendation 5 on support from payers, DHHS/NCI and/or advocacy, provider, or other interest groups could

-

Survey national organizations (e.g., America’s Health Insurance Plans, the National Business Group on Health) about their awareness of and/or advocacy activities related to the recommendations in this report and the initiation of appropriate reimbursement strategies/activities.

-

Monitor and document the emergence of performance reward initiatives (e.g., RFP content on psychosocial care, pay for performance that specifically includes incentives for psychosocial care).

-

Evaluate health plan contracts and state insurance policies for coverage, copayments, and carve-outs for psychosocial services.

-

Assess coverage for psychosocial services for Medicare beneficiaries.

For recommendation 6 on quality oversight, DHHS could

-

Examine the funding portfolios of NIH, CMS, AHRQ, and other public and private sponsors of quality-of-care research to evaluate the funding of quality measurement for psychosocial health care as part of cancer care.

-

Query organizations that set standards for cancer care (e.g., the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the American Society of Clinical Oncology [ASCO], the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer, the Oncology Nursing Society, the American Psychosocial Oncology Society) and other standards-setting organizations (e.g., the National Quality Forum, the National

-

Committee for Quality Assurance, the URAC, the Joint Commission) to determine the extent to which they have

-

-

created oversight mechanisms used to measure and report on the quality of ambulatory cancer care (including psychosocial care);

-

incorporated requirements for identifying and responding to psychosocial health care needs into their protocols, policies, and standards in accordance with the standard of care put forth in this report; and

-

used performance measures of psychosocial health care in their quality oversight activities.

-

For recommendation 7 on workforce competencies, DHHS could

-

Monitor and report on actions taken by Congress and federal agencies to support and fund the establishment of a Workforce Development Collaborative on Psychosocial Care during Chronic Medical Illness.

-

Review board exams for oncologists and primary care providers to identify questions relevant to psychosocial care.

-

Review accreditation standards for educational programs used to train health care personnel to identify content requirements relevant to psychosocial care.

-

Review certification requirements for clinicians to identify those requirements relevant to psychosocial care.

-

Examine the funding portfolios of the NIH, CMS, AHRQ, and other public and private sponsors of quality-of-care research to quantify the funding of initiatives aimed at assessing the incorporation of workforce competencies in education, training, and clinical practice and their impact on achieving the standard for psychosocial care.

For recommendation 8 on standardized nomenclature and recommendation 9 on research priorities, DHHS could

-

Report on NIH/AHRQ actions to develop a taxonomy and nomenclature for psychosocial health services.

-

Examine the funding portfolios of public and private research sponsors to assess whether funding priorities included the recommended areas.

REFERENCES

APA (American Psychiatric Association). 2000. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision (DSM-IV-TR). 4th ed. Washington, DC: APA.

Bayliss, E. A., J. F. Steiner, D. H. Fernald, L. A. Crane, and D. S. Main. 2003. Description of barriers to self-care by persons with comorbid chronic diseases. Annals of Family Medicine 1(1):15–21.

Boberg, E. W., D. H. Gustafson, R. P. Hawkins, K. P. Offord, C. Koch, K.-Y. Wen, K. Kreutz, and A. Salner. 2003. Assessing the unmet information, support and care delivery needs of men with prostate cancer. Patient Education and Counseling 49(3):233–242.

Bruce, M. 2006. A systematic and conceptual review of posttraumatic stress in childhood cancer survivors and their parents. Clinical Psychology Review 26(3):233–256.

Carlsen, K., A. B. Jensen, E. Jacobsen, M. Krasnik, and C. Johansen. 2005. Psychosocial aspects of lung cancer. Lung Cancer 47(3):293–300.

Eakin, E. G., and L. A. Strycker. 2001. Awareness and barriers to use of cancer support and information resources by HMO patients with breast, prostate, or colon cancer: Patient and provider perspectives. Psycho-Oncology 10(2):103–113.

Epstein, R. M., and R. L. Street. 2007. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: Promoting healing and reducing suffering. NIH Publication No. 07-6225. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

Fallowfield, L., D. Ratcliffe, V. Jenkins, and J. Saul. 2001. Psychiatric morbidity and its recognition by doctors in patients with cancer. British Journal of Cancer 84(8):1011–1015.

Hayman, J. A., K. M. Langa, M. U. Kabeto, S. J. Katz, S. M. DeMonner, M. E. Chernew, M. B. Slavin, and A. M. Fendrick. 2001. Estimating the cost of informal caregiving for elderly patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 19(13):3219–3225.

Hegel, M. T., C. P. Moore, E. D. Collins, S. Kearing, K. L. Gillock, R. L. Riggs, K. F. Clay, and T. A. Ahles. 2006. Distress, psychiatric syndromes, and impairment of function in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Cancer 107(12):2924–2931.

Hewitt, M., J. H. Rowland, and R. Yancik. 2003. Cancer survivors in the United States: Age, health, and disability. Journal of Gerontology 58(1):82–91.

Himmelstein, D. U., E. Warren, D. Thorne, and S. Woolhandler. 2005. Market watch: Illness and injury as contributors to bankruptcy. Health Affairs Web Exclusive: DOI 10.1377/hlthaff.W5.63.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1982. Health and behavior: Frontiers of research in the biobehavioral sciences. D. A. Hamburg, G. R. Elliot, and D. L. Parron, eds. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2001. Health and behavior: The interplay of biological, behavioral, and societal influences. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2003. When children die: Improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. M. J. Field and R. E. Behrman, eds. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2006. Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2007. Implementing cancer survivorship care planning. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM and NRC (National Research Council). 2001. Improving palliative care for cancer. K. M. Foley and H. Gelband, eds. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM and NRC. 2003. Childhood cancer survivorship: Improving care and quality of life. M. Hewitt, S. L. Weiner, and J. V. Simone, eds. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM and NRC. 2006. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. M. Hewitt, S. Greenfield, and E. Stovall, eds. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jacobsen, P. B., and S. Ransom. 2007. Implementation of NCCN distress management guidelines by member institutions. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 5(1):93–103.

Jemal, A., L. Clegg, E. Ward, L. Ries, X. Wu, P. Jamison, P. A. Wingo, H. L. Howe, R. N. Anderson, and B. K. Edwards. 2004. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer 101(1):3–27.

Jerant, A. F., M. M. von Friederichs-Fitzwater, and M. Moore. 2005. Patients’ perceived barriers to active self-management of chronic conditions. Patient Education and Counseling 57(3):300–307.

Kangas, M., J. Henry, and R. Bryant. 2002. Posttraumatic stress disorder following cancer. A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology Review 22(4):499–524.

Katon, W. J. 2003. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biological Psychiatry 54(3):216–226.

Keller, M., S. Sommerfeldt, C. Fischer, L. Knight, M. Riesbeck, B. Löwe, C. Herfarth, and T. Lehnert. 2004. Recognition of distress and psychiatric morbidity in cancer patients: A multi-method approach. European Society for Medical Oncology 15(8):1243–1249.

Kelly, M. P., J. Bonnefoy, A. Morgan, and F. Florenza. 2006. The development of the evidence base about the social determinants of health. World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/mekn_paper.pdf (accessed September 26, 2006).

Kotkamp-Mothes, N., D. Slawinsky, S. Hindermann, and B. Strauss. 2005. Coping and psychological well being in families of elderly cancer patients. Critical Reviews in Oncology-Hematology 55(3):213–229.

Kurtz, M. E., J. C. Kurtz, C. W. Given, and B. A. Given. 2004. Depression and physical health among family caregivers of geriatric patients with cancer—a longitudinal view. Medical Science Monitor 10(8):CR447–CR456.

Mallinger, J. B., J. J. Griggs, C. G. Shields. 2005. Patient-centered care and breast cancer survivors’ satisfaction with information. Patient Education and Counseling 57(3):342–349.

Maly, R. C., Y. Umezawa, B. Leake, and R. A. Silliman. 2005. Mental health outcomes in older women with breast cancer: Impact of perceived family support and adjustment. Psycho-Oncology 14(7):535–545.

May, J. H., and P. J. Cunningham. 2004. Tough trade-offs: Medical bills, family finances and access to care. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change.

Merckaert, I., Y. Libert, N. Delvaux, S. Marchal, J. Boniver, A.-M. Etienne, J. Klastersky, C. Reynaert, P. Scalliet, J.-L. Slachmuylder, and D. Razavi. 2005. Factors that influence physicians’ detection of distress in patients with cancer. Can a communication skills training program improve physicians’ detection? Cancer 104(2):411–421.

Ness, K. K., A. C. Mertens, M. M. Hudson, M. M. Wall, W. M. Leisenring, K. C. Oeffinger, C. A. Sklar, L. L. Robison, and J. G. Gurney. 2005. Limitations on physical performance and daily activities among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Annals of Internal Medicine 143(9):639–647.

President’s Cancer Panel. 2004. Living beyond cancer: Finding a new balance. President’s Cancer Panel 2003–2004 annual report. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services.

Riegel, B., and B. Carlson. 2002. Facilitators and barriers to heart failure self-care. Patient Education and Counseling 46(4):287–295.

Ries, L., D. Melbert, M. Krapcho, A. Mariotto, B. Miller, E. Feuer, L. Clegg, M. Horner, N. Howlader, M. Eisner, M. Reichman, and B. E. Edwards. 2007. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2004. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

Schultz, R., and S. R. Beach. 1999. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The caregiver health effects study. Journal of the American Medical Association 282(23):2215–2219.

Segrin, C., T. A. Badger, P. Meek, A. M. Lopez, E. Bonham, and A. Sieger. 2005. Dyadic interdependence on affect and quality-of-life trajectories among women with breast cancer and their partners. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 22(5):673–689.

Segrin, C., T. Badger, S. M. Dorros, P. Meek, and A. M. Lopez. 2007. Interdependent anxiety and psychological distress in women with breast cancer and their partners. Psycho-Oncology 16(7):634–643.

Skalla, K. A., M. Bakitas, C. T. Furstenberg, T. Ahles, and J. V. Henderson. 2004. Patients’ need for information about cancer therapy. Oncology Nursing Forum 31(2):313–319.

Spiegel, D., and J. Giese-Davis. 2003. Depression and cancer: Mechanism and disease progression. Biological Psychiatry 54(3):269–282.

Spitzer, R. L., K. Kroenke, M. Linzer, S. R. Hahn, J. B. Williams, F. V. deGruy, D. Brody, and M. Davies. 1995. Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with mental disorders. Results from the PRIME-MD 1000 study. Journal of the American Medical Association 274(19):1511–1517.

Subramanian, S., P. Belli, and I. Kawachi. 2002. The macroeconomic determinants of health. Annual Review of Public Health 23:287–302.

Tu, H. T. 2004. Rising health costs, medical debt and chronic conditions. Issue Brief No. 88. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change.

USA Today, Kaiser Family Foundation, and Harvard School of Public Health. 2006. National survey of households affected by cancer: Summary and chartpack. Menlo Park, CA, and Washington, DC: USA Today, Kaiser Family Foundation, and Harvard School of Public Health. http://www.kff.org/Kaiserpolls/upload/7591.pdf (accessed April 24, 2007).

Wdowik, M. J., P. A. Kendall, and M. A. Harris. 1997. College students with diabetes: Using focus groups and interviews to determine psychosocial issues and barriers to control. The Diabetes Educator 23(5):558–562.