4

A Model for Delivering Psychosocial Health Services

CHAPTER SUMMARY

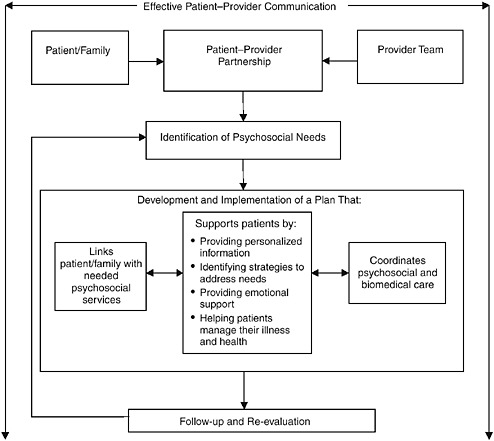

Many different providers of health services—some in oncology, some delivering health care for other complex health conditions—recognize that psychosocial problems can have both direct and indirect effects on health and have developed interventions to address them. Some of these interventions are derived from theoretical or conceptual frameworks; some are based on research findings; and some have undergone empirical testing. The best have all three characteristics. When viewed together, these interventions evidence common elements that point to a model for the effective delivery of psychosocial health services. The components of this model include (1) identifying patients with psychosocial health needs that are likely to affect their health or health care, and developing with patients appropriate plans for (2) linking patients to appropriate psychosocial health services, (3) supporting patients in managing their illness, (4) coordinating psychosocial with biomedical health care, and (5) following up on care delivery to monitor the effectiveness of services and determine whether any changes are needed. Effective patient–provider communication is central to all of these components.

EFFECTIVE DELIVERY OF PSYCHOSOCIAL HEALTH CARE

The committee conducted a search1 to identify empirically validated models of the effective delivery of psychosocial health services. This search

|

1 |

This search involved reviewing peer-reviewed literature, seeking recommendations from experts in the delivery of cancer and other complex health care (experts contacted are listed in Appendix B), and investigating models otherwise identified by the committee. |

yielded a number of models tested and found to be effective in delivering these services and improving health. These models are described in Annex 4-1 at the end of this chapter and are listed in Table 4-1, which highlights components common to many or all of them: (1) identifying patients with psychosocial health needs that are likely to affect their ability to receive health care and manage their illness, and developing with patients appropriate plans for (2) linking patients to appropriate psychosocial health services, (3) supporting them in managing their illness, (4) coordinating psychosocial with biomedical health care, and (5) following up on care delivery to monitor the effectiveness of services and determine whether any changes are needed. Table 4-1 also includes practice guidelines, produced through systematic reviews of evidence, that identify approaches for the effective delivery of psychosocial health services, along with the consensus-based guidelines for Distress Management developed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)—an alliance of 21 leading U.S. cancer centers. The various ways in which these programs carry out some of these functions also are listed in the table and elaborated on in the text that follows.

Evidence derived from the models listed in Table 4-1 (summarized in Annex 4-1) strongly suggests that a combination of activities rather than any single activity by itself (e.g., screening, case management, illness self-management) is needed to deliver appropriate psychosocial health care effectively to individuals with complex health conditions. This conclusion also is supported by the findings of several systematic reviews of psychosocial care. For example, not surprisingly, screening by itself is less effective than screening with follow-up. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, for instance, recommends screening for depression in adults in clinical practices only when practices have systems in place to ensure effective follow-up treatment and ongoing monitoring. This recommendation reflects research finding that only small benefits result from screening by itself, but larger benefits when screening is accompanied by effective follow-up (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2002). Consistent with this finding, a review of studies of interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care settings found that those with the most multidimensional approaches (such as case management combined with clinician education and structured links to connect primary and specialty medical care) were most likely to achieve desired outcomes (Gilbody et al., 2003). Another systematic review of randomized controlled trials designed to improve the use of needed health and social services after hospital discharge found that interventions emphasizing follow-up on the results of a needs assessment showed more positive results than needs assessment alone (Richards and Coast, 2003).

In this chapter, the committee recommends a unifying model for plan-

TABLE 4-1 Models for Delivering Psychosocial Health Services and Their Common Components

|

Model |

Common Componentsa |

|||||

|

Identification of Patients with Psychosocial Health Needs |

Care Planning to Address Those Needs |

Mechanisms to Link Patients to Psychosocial Health Services |

Support for Illness Self-Management |

Mechanisms for Coordinating Psychosocial and Biomedical Care |

Follow-up on Care Delivery |

|

|

Building Health Systems for People with Chronic Illnesses (Palmer and Somers, 2005) |

Risk and eligibility screening |

Yes |

Care managementb |

Yes |

Multidisciplinary team care |

Outcome measurement |

|

Needs assessment |

|

|

|

Pooled funding |

|

|

|

Chronic Care Model (ICIC, 2007) |

No |

Yes |

Linkage to community resources |

Yes |

Clinical information systems |

Use of information systems to accomplish this |

|

|

|

|

|

Team care |

|

|

|

|

|

Case management for complex cases |

|

|

Planned or structured follow-up visits |

|

|

Clinical Practice Guidelines for Distress Management (NCCN, 2007a) |

Screening for distress |

Yes |

Social work and referral services |

No |

Coordination of oncology team |

Yes |

|

Needs assessment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Model |

Common Componentsa |

|||||

|

Identification of Patients with Psychosocial Health Needs |

Care Planning to Address Those Needs |

Mechanisms to Link Patients to Psychosocial Health Services |

Support for Illness Self-Management |

Mechanisms for Coordinating Psychosocial and Biomedical Care |

Follow-up on Care Delivery |

|

|

Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Psychosocial Care of Adults with Cancer (National Breast Cancer Centre and National Cancer Control Initiative, 2003) |

Screening for anxiety/depression |

No |

Development of referral pathways and networks |

No |

Multidisciplinary team care |

Yes |

|

Coordinator of care designated by patient |

Coordinator of care designated by patient |

|||||

|

Collaborative Care of Depression in Primary Care (Katon, 2003) |

Use of standardized screening and diagnostic tools for depression |

Yes |

Structured, formal arrangement for psychiatric consultation |

Yes |

Case conferences |

Surveillance of medication use and patient outcomes |

|

Mental health specialists located within primary care sites |

||||||

|

Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer (NICE, 2004) |

Needs assessment |

Yes |

Yes |

Identified as part of rehabilitation services |

Multiple strategies including, e.g., multidisciplinary teams, information systems, patient-held records |

Yes |

FIGURE 4-1 Model for the delivery of psychosocial health services.

ning and delivering psychosocial health care for patients with cancer. This model is based on the evidence yielded by the models listed in Table 4-1, evidence suggesting added value from multiple components of effective care delivery, and evidence (presented below) supporting the contributions of many of these individual components to the effective provision of psychosocial health care. The committee’s model, illustrated in Figure 4-1, integrates the five common components identified above. Although these components individually are in some cases supported by research findings, in other cases there may not be strong evidence of their effectiveness as stand-alone interventions. Nonetheless, the committee recommends their inclusion based on their presence in the reviewed models and with the understanding that

a lack of research findings is not necessarily synonymous with ineffectiveness.2 We also note that effective patient–provider communication is central to the success of all five components of the model. The model is described in detail below.

A UNIFYING MODEL FOR CARE DELIVERY

Effective Patient–Provider Communication

At the heart of the committee’s model is a well-functioning patient–provider partnership, characterized, in large part, by effective communication. Communicating effectively means that patients are able to receive and understand information about their illness and health care, and clearly express their needs for assistance and the values and personal resources that will shape the health care system’s response to these needs. Patients should be comfortable with asking questions of all their care providers and equally comfortable with responding to questions posed to them. They should be competent and at ease as a member of their own health care team, which will make decisions about the best strategy for addressing their illness. Patients with language barriers, cognitive deficits, or other impediments to communication should receive assistance in overcoming these barriers to effective communication.

In many instances, members of the patient’s family also are involved in this communication. In pediatric cases, a family member may be the primary communicator and participant in planning care; with adults, some patients may also have limited capacity to communicate. Even when adult patients are able to communicate, as discussed in Chapters 1 and 2, family members are key caregivers, especially for older adults. Treatment planning and planning for managing the effects of illness requires communication with the patient’s caregivers as well as with the patient. When patients do not have the capacity to participate actively themselves, there needs to be an explicit substitute who is legally and psychologically able to act as the patient’s advocate.

Care providers similarly should possess the communication skills necessary to be effective clinicians and supportive partners in care—a hallmark of high-quality health care (IOM, 2001) and health care professionals (IOM, 2003). These communication skills include establishing a good interpersonal relationship with the patient (Arora, 2003). Key aspects of

|

2 |

For example, an intervention may be so obviously helpful (e.g., providing transportation to help those without means to get to their appointments to do so) that it (rightly) has not been a priority for research (see Chapter 3), or a research design may not have been sufficient to detect the outcome of interest. |

effective patient–clinician communication identified in the National Cancer Institute (NCI) report Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care include (1) fostering healing relationships, (2) exchanging information, (3) responding to emotions, (4) managing uncertainty, (5) making decisions, and (6) enabling patient self management (Epstein and Street, 2007). As described in Chapter 1, however, these attributes are not commonly found in cancer care today.

Current Patient–Provider Communication

Most patients, including those with cancer, say they want more information from their physicians (Guadagnoli and Ward, 1998; Wong et al., 2000; Gaston and Mitchell, 2005; Kahán et al., 2006; Kiesler and Auerbach, 2006). Patients report being dissatisfied with the limited information they receive and when they receive it. Clinicians often have a limited understanding of patients’ information needs, knowledge, and concerns. As a result, they fail to provide the type or amount of information patients need and communicate in language that patients often do not understand (Kerr et al., 2003a,b; Kahán et al., 2006; Epstein and Street, 2007). Clinicians’ delivery of bad news is particularly problematic. Conversely, patients do not always disclose relevant information about their symptoms or concerns (Epstein and Street, 2007).

Further, the majority of patients (ranging in studies from 60 to 90 percent) say that they prefer either an active or shared/collaborative role in decisions made during office visits (Mazur and Hickman, 1997; Guadagnoli and Ward, 1998; Dowsett et al., 2000; Wong et al., 2000; Gattellari et al., 2001; Bruera et al., 2002; Davison et al., 2002, 2003; Keating et al., 2002; Davison and Goldenberg, 2003; Janz et al., 2004; Gaston and Mitchell, 2005; Katz et al., 2005; Mazur et al., 2005; Ramfelt et al., 2005; Siminoff et al., 2005; Flynn et al., 2006; Hack, 2006). However, studies show that physicians substantially underestimate patients’ desire for an active or shared role in their care (Bruera et al., 2002; Janz et al., 2004; Kahán et al., 2006).

Some physicians, particularly female and primary care physicians, have a more participatory or collaborative style with patients (Kaplan et al., 1996; Cooper-Patrick et al., 1999; Roter et al., 2002; Street et al., 2003). Lower levels of participatory decision making among physicians have been associated with several patient characteristics, including age, education, and minority status (Kaplan et al., 1996; Cooper-Patrick et al., 1999; Adams et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2004), although these patient characteristics do not account for the majority of the variation in conversational behavior among either physicians or patients during office visits (Kaplan et al., 1995; Benbassat et al., 1998). There is evidence that physicians and

patients mutually influence each other’s conversational behavior (Robinson and Roter, 1999; Del Piccolo et al., 2002; Street et al., 2003, 2005; Butow et al., 2004; Janz et al., 2004; Maly et al., 2004; Gordon et al., 2005; Kindler et al., 2005; Adler, 2007) and that physicians may take their cues in part from patients, who typically exhibit relatively passive behavior during office visits (Gordon et al., 2005, 2006a,b; Street and Gordon, 2006). Such passivity characterizes even physicians when they become patients. The average patient asks five or fewer questions during a 15-minute office visit, and many ask no questions (Brown et al., 1999, 2001; Sleath et al., 1999; Cegala et al., 2000; Butow et al., 2002; Bruera et al., 2003; Kindler et al., 2005). Among the most passive patients are those above age 60, those with more severe illness or multiple comorbid conditions (including psychological distress), those who are less well educated, and males (Butow et al., 2002; Sleath and Rubin, 2003; Street et al., 2003; Maliski et al., 2004; Gaston and Mitchell, 2005; Flynn et al., 2006; Gordon et al., 2006b; Siminoff et al., 2006a). Minorities also have been noted to be more passive in physician–patient interactions (Gordon et al., 2005; Street et al., 2005; Siminoff et al., 2006a; Gordon et al., 2006b). Moreover, a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and uncontrolled studies of interventions designed to improve the provision of information and encourage participation in decision making by patients with advanced cancer found that although almost all patients expressed a desire for full information, only about two-thirds wished to participate actively in decision making about their care (Gaston and Mitchell, 2005).

Correspondence between patients’ preferred role in decision making and their actual role during office visits with physicians, although intuitively compelling, has relatively little empirical support as a factor affecting patient outcomes and quality of care. However, such correspondence has been linked with reduced anxiety (Gattellari et al., 2001; Kahán et al., 2006) and depression (Schofield and Butow, 2003), satisfaction with treatment choices (Keating et al., 2002), and more appropriate treatment choices (Siminoff et al., 2006b). The NCI report Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care articulates a comprehensive research agenda for better understanding and intervening to improve patient–provider communication (Epstein and Street, 2007).

The Importance of Communication

There is reason to be concerned about findings of poor communication and lack of patient involvement. A substantial body of evidence indicates that effective physician–patient communication is positively related to patients’ health outcomes (Kaplan et al., 1989; Stewart, 1995; Piccolo et al., 2000; Heisler et al., 2002; Engel and Kerr, 2003; Kerr et al., 2003a,b;

Schofield and Butow, 2003; Maliski et al., 2004). Patients of physicians who involve them in treatment decisions during office visits have better health outcomes than those of physicians who do not (Kaplan et al., 1995; Adams et al., 2001; Gattellari et al., 2001; Hack et al., 2006). Physicians’ participatory decision-making style also is positively related to the quality and outcomes of patient care generally (Guadagnoli and Ward, 1998), including continuity of care (Kaplan et al., 1996), health outcomes (Adams et al., 2001; van Roosmalen et al., 2004), decreased psychological distress (Zachariae et al., 2003), trust in the physician (Berrios-Rivera et al., 2006; Gordon et al., 2006a,b), more preventive health services (Woods et al., 2006), better communication with physicians (Thind and Maly, 2006), and satisfaction with care (Kaplan et al., 1996; Adams et al., 2001). Similar benefits are found specifically in cancer care (Arora, 2003).

Interventions to Improve Communication

Many clinicians have identified a need for stronger communication skills for themselves, their patients, and families. Interventions to improve physician–patient communication have targeted either physicians or patients; few have targeted both simultaneously (Epstein and Street, 2007).

Training physicians to negotiate with patients has been found to increase patient involvement in treatment decisions (Timmermans et al., 2006). A substantial literature also documents the effects of interventions aimed at improving patients’ participation in their care (Epstein and Street, 2007). Such interventions include those aimed at improving patients’ participation in multiple decisions over multiple visits with physicians (e.g., question asking, decision elicitation, and negotiation skills), enhancing the presentation of options, tailoring risk information, and providing testimonials describing outcomes of treatment to help patients participate in single or discrete decisions and improve information seeking (question asking).

The means used to deliver these interventions also vary widely. “Coached care” for chronic disease makes use of patient medical records, guidelines for clinical care management reviewed with patients before office visits, and coaching in using information to participate effectively with physicians. This approach has been linked with improved physiological and functional patient outcomes and increased patient participation in physician–patient communication among patients with chronic disease (Greenfield et al., 1988; Kaplan et al., 1989; Rost et al., 1991; Keeley et al., 2004). Decision aids to assist patients in choosing among treatment options have been shown to decrease decisional conflict, increase satisfaction with treatment decisions (Whelan et al., 2004), and decrease adjuvant therapy for low-risk patients with breast cancer (Peele et al., 2005; Siminoff et al., 2006b).

An extensive literature documents the beneficial effects of interactive videos presenting treatment options, tailored risk information, and patient

testimonials describing outcomes of treatment. Benefits include improved functional outcomes, increased confidence in treatment, and increased satisfaction with decision making (Flood et al., 1996; Liao et al., 1996; Barry et al., 1997). Following similar interventions, others have noted changes in patients’ treatment choices, favoring less invasive treatment (Mazur and Merz, 1996). O’Connor and colleagues (1995) note that these types of decision aids, compared with usual care, yield improvements in patients’ knowledge of their disease and its treatment, more realistic expectations, less decisional conflict, more active participation in office visits, and less indecision about options. No effect on patient anxiety was observed. Videos with or without supporting materials have been shown to enhance patients’ understanding of treatment options (Onel et al., 1998) and physician–patient communication during office visits (Frosch et al., 2001; Brown et al., 2004a). In a review of small media interventions, counseling and small-group education sessions, or a combination of these approaches, Briss and colleagues (2004) found that while such interventions increased patients’ knowledge about their disease and the accuracy of their risk perceptions, whether such interventions lead to increased patient participation in treatment decisions has been less well studied.

Other interventions to improve patient participation in care, such as the use of question-prompt sheets, audiotaping of visits, or more basic decision aids, have been linked with greater patient involvement in treatment decisions (Butow et al., 1994; Guadagnoli and Ward, 1998; Cegala et al., 2000; Maly et al., 2004; Gaston and Mitchell, 2005).

Conclusions

Despite strong evidence for the importance of effective patient–provider communication and patients’ participation in decision making in achieving better health care outcomes, such communication is not yet the norm. As described above and in Chapter 1, physician–patient communication is generally inadequate, and patients are poorly prepared for communicating effectively (whether this involves simple information-seeking skills or more active involvement in treatment decisions). Physicians, too, are poorly prepared to elicit patients’ information needs and preferences for involvement in their care. There is a need for more creative and intensive interventions to enhance patient–physician communication and support patient decision making, targeting in particular those most at risk (e.g., older adults, those of lower socioeconomic status, and those with comorbid conditions including psychosocial distress and decreased cognition). Many approaches are being tested to meet this need. These approaches require more rigorous evaluation, especially in less well-organized health care settings.

NCI’s state-of-the-science report on patient-centered communication in cancer care (Epstein and Street, 2007) can inform clinical practice, as well

as research. This report finds that most skill-building interventions targeting clinicians consist of formal training as part of medical education or continuing education programs (e.g., a 3-day course on communication skills) to increase clinician knowledge and improve communication behaviors. Very little research has focused on changing clinical practices and health care systems. With respect to clinician education and training programs, the report finds that the most effective communication skill-building programs are those that are carried out over a long period of time, use multiple teaching methods, allow for practice, provide timely feedback, and allow clinicians to work in groups with skilled facilitators. The report also finds that because clinicians develop routines for interacting with patients early in their careers, communication training should occur early in professional education. Clinicians should seek out such opportunities for communication training as part of their continuing education activities. Training is available from such sources as the Institute for Healthcare Communication (http://www. healthcarecomm.org/index.php) to improve knowledge, skills, and clinical practice in communication with patients.

With respect to improved patient communication, use of tools to support communication and formal strategies to teach communication techniques to patients have been found effective in improving communication with clinicians. These tools and techniques include encouraging patients to write down their questions and concerns prior to meeting with clinicians; providing written “prompts” to patients that serve as reminders of key questions or issues; and providing information and decision aids about the illness, treatment, and health through booklets, videos, coaching sessions, and use of diaries (Epstein and Street, 2007). Patient advocacy organizations can play an important role in strengthening the patient side of the patient–provider partnership through the provision of such tools and training. An example is the Cancer Survival Toolbox (available free of charge), which teaches people with cancer how to obtain information, make decisions, solve problems, and generally communicate more effectively with health care providers (Walsh-Burke et al., 1999; NCCS, 2007).

Identifying Patients with Psychosocial Health Needs

Identifying psychosocial health needs is the essential precursor to meeting those needs. This can occur in several ways: (1) patients may volunteer information about these needs in their discussions with health care providers; (2) providers may ask about psychosocial health needs during structured or unstructured clinical conversations with the patient; (3) providers may screen patients using validated instruments; and (4) providers may perform an in-depth psychosocial assessment of patients after or independently of screening. These approaches vary considerably in their reliability and their sensitivity in uncovering patients’ needs.

Relying on patients to volunteer information or on providers to elicit it in the course of standard care both are unlikely to be adequate. A study of the ability of medical oncologists and nurses in the United States to recognize on their own the psychosocial problems of their oncology patients found that these providers frequently failed to detect depression at all and when they did, greatly underestimated its seriousness (Passik et al., 1998; McDonald et al., 1999). This finding parallels data on the low rate of detection of depression in primary care settings when depression screening tools are not used. And while there is evidence for the effectiveness of structured clinical interviews in detecting some psychosocial needs (e.g., for treatment of depression), this approach is criticized for the amount of time it takes and the requirement for specialized (costly) personnel to conduct the interviews (Trask, 2004). Patients’ reluctance to volunteer information about their need for psychosocial services (Arora, 2003) can also impede the detection of problems.

In contrast, several screening tools and in-depth needs assessment instruments have been found to be effective in reliably identifying individuals with psychosocial health needs. Screening involves the administration of a test or process to individuals who are not known to have or do not necessarily perceive that they have or are at risk of having a particular condition or need. It is used to identify those who are likely to have a condition of interest and should benefit from its detection and treatment. A screening instrument yields a yes or no answer as to whether an individual is at high risk. A positive screen should be followed by a more in-depth needs assessment. In some practices, needs assessment may be performed without a preceding screen.

Screening

Many screening instruments are brief and can be self-administered by the patient—sometimes in the waiting room before a visit with the clinician. Instruments range from the low-tech, requiring only paper and pencil, to the high-tech, using a computer-based touch screen; some of the latter instruments automatically compare responses with those given previously and generate an automatic report to the clinician. The success of many practices in using such screening tools counters generalizations that patients are unwilling to discuss psychosocial concerns. Still, as discussed below, too few clinicians employ these reliable methods routinely to identify patients with psychosocial health needs.

Current practice Screening for psychosocial health needs using validated instruments is not routinely practiced in oncology. In a national survey3 of

1,000 randomly selected members of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 14 percent of respondents reported screening for psychosocial distress using a standardized tool. A third reported that they did not routinely screen for distress. Of the 65 percent that did routinely screen, 78 percent did so using some combination of asking direct questions (61 percent), such as “How are you coping?”, “Are you depressed?”, or “How do you feel?”; observing patients’ moods (57 percent); taking their history (53 percent); talking to family members (44 percent); or other methods. Similarly, of 15 organizations responding to a survey of 18 member institutions of NCCN, only 8 reported that they routinely screened for distress in at least some of their patients. Of these 8, 3 screened as part of a patient interview, 2 used a self-report measure, and 3 used both. Only 3 routinely screened all of their patients; the majority screened only certain groups of patients, such as those undergoing bone marrow transplantation or those with breast cancer (Jacobsen and Ransom, 2007).

Reasons given by individual oncologists for not screening include a lack of time, a perception of limited referral resources, a belief that patients are unwilling or resistant to discussing distress, and uncertainty about identifying and treating distress.4 Reasons given by member institutions of NCCN for not screening include screening not considered necessary or worthwhile (one institution), not enough resources to address those identified by a screener as needing care (one institution), and insufficient resources to both screen and address identified needs (one institution). The other institutions reported that they were currently in the process of pilot testing procedures for routine screening for distress (Jacobsen and Ransom, 2007).

The above concerns may not be justified. The experiences of those who have developed or now use screening tools show that screening need not take much time and that patients are willing to communicate their distress. Further, research shows that physicians’, nurses’, and other personnel’s individual assessments of the levels of stress experienced by patients or their family members are less accurate than a standardized instrument (Hegel et al., 2006). Although there remain some unresolved issues in screening that could be addressed by further research (see Chapter 8), the research and implementation examples reviewed below and in Chapter 5 demonstrate that screening can be both an effective and a feasible mechanism for identifying individuals with psychosocial health needs. The variation among existing validated screening instruments can facilitate the inclusion of screening in routine clinical practice by accommodating the differing interests and resources of various clinical sites. Patient Care Monitor (PCM), for example, is automated and part of a comprehensive patient assessment, care, and education system. Other instruments, such as the

Distress Thermometer, require nothing more than paper and pencil. Most are administered by patients themselves. Although some must be purchased commercially and require a licensing agreement and fee, others are available at no cost.

Screening tools In addition to having strong predictive value,5 effective screening tools should be brief and feasible for routine use in various clinical settings. Such tools are available for screening patient populations and identifying individuals with some types of psychosocial health care needs. For example, a number of screening tools for detecting mental health problems, such as anxiety, depression, adjustment disorders, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSS), have been tested with cancer survivors in different oncology settings and found to meet these criteria. The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)©-18, for example, measures depression, anxiety, and overall psychological distress level in approximately 4 minutes (Derogatis, 2006). Its reliability, validity, sensitivity, and specificity have been documented in tests involving more than 1,500 cancer patients with more than 35 different cancer diagnoses (Zabora et al., 2001), as well as adult survivors of childhood cancer (Recklitis et al., 2006). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) also is useful in screening individuals with cancer or other illnesses for psychological distress because its 14-item, self-report questionnaire omits measures of fatigue, pain, or other somatic expressions of psychological distress that could instead be symptoms of physical illness and confound the interpretation of screening results (Zigmond and Snaith, 1983). Other useful psychological screening tools include, for example, the Brief Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale; Rotterdam Symptom Checklist; Beck Depression Inventory-Short Form (Trask, 2004); PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (Andrykowski et al., 1998); Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), SF (Short Form)-8; 4-item Primary Care PTSD Screen (Hegel et al., 2006); and PHQ-9 (Lowe et al., 2004).

However, in addition to unresolved questions about the appropriate use and interpretation of the results obtained with these psychological screening tools (Trask, 2004; Mitchell and Coyne, 2007), their varying foci necessitate either administering multiple tools—infeasible for most clinical

settings6—or choosing among them. No guidance exists with respect to which tools should be used for the different types of patients seen in various clinical settings. Moreover, these tools do not screen for the broader array of psychosocial health needs. If, for example, an individual has inadequate social support or financial resources but perceives this situation as the norm or does not experience clinically significant anxiety or depression, these screening instruments may not identify this individual as having psychosocial health needs. In a small study of distress in 50 candidates for bone marrow transplantation, patient reports of distress were found to be accounted for only in part by depression and/or anxiety, suggesting that patients’ experiences of distress “were not adequately captured by simple measures of anxiety and depression (the HADS)” and that the “patient definition of distress is qualitatively different from symptoms of anxiety and depression” (Trask et al., 2002:923). Other studies also have observed variable results from the use of different screening instruments (Hegel et al., 2006).

Thus, there is a need for psychosocial screening instruments that can accurately and efficiently detect a comprehensive range of health-related psychosocial problems—including difficulties with logistical or material needs (e.g., transportation or insurance), inadequate social supports, behavioral risk factors, and emotional problems such as anxiety or depression. Although few in number, instruments that can be used to screen for a broader array of psychosocial needs exist. These instruments vary somewhat in their content and approach, which may reflect their different purposes and conceptual bases (as well as the absence of a shared understanding of health-related psychosocial stress and psychosocial health services, as discussed in Appendix B). Although additional testing of these instruments would be beneficial, the validity, reliability, and feasibility of some are sufficiently established that many oncology practices now routinely screen all of their patients for psychosocial health needs using such instruments as those described below.

The Distress Thermometer uses a visual analogue scale displayed on a picture of a thermometer to screen for any type of psychological distress. Individuals are instructed to circle the number (from zero [no distress] to 10 [extreme distress]) that best describes how much distress they have experienced over the past week (NCCN, 2006). The single-item, paper-and-pencil Distress Thermometer is self-administered in less than a minute. Testing

in individuals with different types of cancer at multiple cancer centers has shown that a rating of 4 or higher correlates with significant distress and that the instrument affords good sensitivity and specificity (Jacobsen et al., 2005). Testing has also revealed concordance with the HADS and BSI (Roth et al., 1998; Trask et al., 2002; Akizuki et al., 2003; Hoffman et al., 2004; Jacobsen et al., 2005). In guidelines issued by NCCN, a 35-item Problem List provided on the same page as the thermometer asks patients to identify separately the types of problems they have (e.g., financial, emotional, work-related, spiritual, family, physical symptoms) (NCCN, 2006). This tool can help identify psychosocial problems that are not linked to psychological distress, as well as those that are. The Problem List does not ask about behaviors such as smoking, alcohol or drug use, exercise, or diet or about cognitive problems that could interfere with illness self-management. The Distress Thermometer is available at no cost from NCCN. No data are available on the extent of its use overall, although three member cancer centers of NCCN report using it (Jacobsen and Ransom, 2007).

The Patient Care Monitor (PCM) 2.0 is an automated, 86-item screening tool that reviews psychological status, problems in role functioning, and overall quality of life, as well as physical symptoms and functioning. Designed to screen for patient problems frequently encountered by practicing oncologists, it is completed by the patient using a computer-based tablet and pen prior to each visit with the clinician. The questionnaire takes an average of 11 minutes to complete. Once completed, it is sent automatically via secure wireless connection to a central server at the practice site; responses are compared with those given previously; and the results are printed out for review by the clinician prior to the visit with the patient. Scores for distress and despair/depression are automatically generated and included in the PCM report. Measures of the instrument’s validity and reliability for use with adults have been favorable in testing among multiple convenience samples of patients in one large oncology practice (Fortner et al., 2003; Schwartzberg et al., 2007). PCM has not undergone tests of its sensitivity and specificity; however, a threshold for follow-up assessment has been established using normalized T scores derived from a normative database created from data submitted by licensed users. At present, a score of 65 is more than 1 standard deviation beyond the mean and represents the top 5 percent for either distress or despair/depression. Patients with scores of 65 or higher are strongly recommended to receive further assessment. PCM is a component of the PACE (Patient Assessment, Care, and Education) product, commercially available from the Supportive Care Network, and has a Spanish version. As of January 2007, it was in use by more than 110 oncology practices in the United States.

The Psychosocial Assessment Tool© (PAT) 2.0 was developed for use with families of children newly diagnosed with cancer to assess the patient’s

level of risk for psychosocial health problems during treatment. Risk factors for which it screens pertain to family structure and resources, social support, children’s knowledge of their disease, school attendance, children’s emotional and behavioral concerns, marital/family problems, family beliefs, and other family stressors (Kazak et al., 2001). PAT differs from the Distress Thermometer and PCM in that it was developed for children and for one-time use, although the developers report interest in its periodic use.7

The first version of PAT was pilot tested with 107 families and found to be feasible for routine use as a self-report instrument completed by families (Kazak et al., 2001). The 2.0 version includes modifications to improve clarity, ease of use, and content and can be completed in approximately 10 minutes. In subsequent testing, total scores on PAT 2.0 were significantly correlated in the predicted direction with parents’ acute distress, anxiety, and conflict and children’s behavioral symptoms, as well as with lower family cohesion. Favorable construct, criterion-related, and convergent validity were found as compared with established tools for measuring children’s behavior, parents’ anxiety and acute stress, and family functioning, as well as with physician- and nurse-completed versions of PAT. Results of tests of internal consistency and test–retest reliability have also been favorable. Cut-off scores for identifying varying levels of need have been determined a priori on the basis of research on the original PAT. As of January 2007, PAT 2.0 was recommended only for research purposes, although its developers believe that upon publication of the most recent research findings, there will be interest in its clinical use and that it is suitable for such use.8

Psychosocial Screen for Cancer (PSSCAN) is a 21-item tool that measures perceived social support (instrumental, emotional, network size), desired social support, anxiety, depression, and quality of life. Developed by the British Columbia Cancer Agency (BCCA) of Canada, it has performed well on psychometric tests and tests of reliability and validity in three samples totaling almost 2,000 patients. PSSCAN is in clinical use in a few Canadian cancer centers, although BCCA is committed to its use by all new patients. It also is being used in Ireland and in some U.S. facilities. BCCA has formulated norms for a healthy population (based on a sample size of 800; manuscript in preparation) and has developed software for the tool’s use on touch-screen computers. This software has been pilot tested with cancer patients and is ready for large-scale use. The questionnaire can be completed in less than 10 minutes by all patients (except those who do not read English or have severe problems with eye or motor control). The

software also autoscores all items on completion and prints a one-page summary of scored data for immediate staff use and incorporation into patient charts. Raw data are automatically deposited into an Excel data file for later processing with standard statistical packages. PSSCAN is available at no cost (Linden et al., 2005).9

Other screening tools also exist and have been subjected to or are in various stages of testing. Some of these are simple checklists to identify psychosocial health needs (Pruyn et al., 2004). Although there are reports on pilot tests of the feasibility of these checklists, they have not undergone further testing for their validity, reliability, or predictive value as screens. However, a review of six studies of the use of checklists to identify psychosocial health needs in cancer care found that use of these screening tools positively influenced health care providers to pay attention to psychosocial health needs, talk with their patients about these needs, and make referrals to providers of psychosocial health services (Kruijver et al., 2006).

Assessment

In the absence of a common definition of needs assessment and descriptions of how it relates to screening,10 in this report psychosocial needs assessment is defined as the identification and examination of the psychological, behavioral, and social problems of patients that interfere with their ability to participate fully in their health care and manage their illness and its consequences. Needs assessment contrasts with screening in that the latter is a brief process for identifying the risk for having psychosocial health needs, while needs assessment is a more in-depth evaluation that confirms the presence of such needs and describes their nature. Needs assessment thus requires more time than screening.

Full understanding of each individual’s psychosocial problems and resulting needs is frequently cited as an essential precursor to ensuring that cancer patients receive the necessary psychosocial health services (NICE,

2004), to providing good-quality health care overall, and to improving health-related quality of life (Wen and Gustafson, 2004). The United Kingdom’s National Institute for Clinical Evidence recommends, for example, that “assessment and discussion of patients’ needs for physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and financial support should be undertaken at key points (such as at diagnosis; at commencement, during, and at the end of treatment; at relapse; and when death is approaching)” (NICE, 2004:7). Needs assessments are theorized to facilitate communication between patients and providers about issues that are not otherwise raised (Wen and Gustafson, 2004).

A systematic review of randomized trials (Gilbody et al., 2002) and one cancer-specific randomized pilot project (Boyes et al., 2006) addressing needs assessment used by itself or with minimal follow-up (such as feedback of results to clinicians) found little support for the effectiveness of the process in improving psychosocial functioning. When combined with follow-up care planning and implementation of those plans, however, needs assessment was found to be effective in improving access to needed services in a systematic review of randomized controlled trials evaluating the effectiveness of interventions in improving access to services after hospital discharge11 (Richards and Coast, 2003). In another systematic review and meta-analysis, systematic assessment of medical, functional, psychosocial, and environmental domains and follow-up implementation of an intervention plan were found to be effective in preventing functional decline in older adults (Stuck et al., 2002). Needs assessment was also identified as one essential ingredient in reduced hospital admissions or medical costs in a qualitative analysis of effective care coordination programs for Medicare (Chen et al., 2000). These findings are consistent with that of the committee that a combination of activities, rather than a single activity by itself (in this case, needs assessment), is needed for the effective delivery of appropriate psychosocial health care.

A systematic search by Wen and Gustafson (2004) for needs assessment instruments for patients with cancer revealed 17 patient and 7 family instruments (generally self-report) for which information was available on their reliability, validity, burden, and psychometric properties (see Table 4-2). These instruments varied greatly in the needs addressed,12 the domains

covered, and the items included in similarly named domains (see Table 4-3). Reviewers also found a lack of evidence for the instruments’ sensitivity to change over time, failure to examine their required reading levels, and failure to address the period after initial treatment for cancer. Despite these deficiencies and the need for further research (see Chapter 8), results of the two systematic reviews that examined the use of needs assessment instruments when processes for follow-up on identified needs were implemented, as well as the reasonableness of needs assessment as a means of identifying individuals who need psychosocial health services, argue for the usefulness of the process as a prelude to the planning and provision of such services. This conclusion also is supported by the models for delivering psychosocial health services contained in Table 4-1.

Planning Care to Address Identified Needs

Once psychosocial health needs have been identified, a plan should be developed that will assist the patient in managing his or her illness and maintaining the highest possible level of functioning and well-being. Nearly all of the models for delivering psychosocial health services reviewed by the committee (Table 4-1) identify care planning as a component of the intervention. This inclusion of planning may originate from (1) the long-standing practice of developing treatment or care plans as a part of routine medical, nursing, and other health care; (2) the logic of developing a plan for action before action is taken; and/or (3) the identification of care planning in some research as an essential to improving health care. Although care planning in itself has not been the subject of much health services research, some research identifies it as one ingredient in effective interventions to improve health care outcomes in adults with chronic illnesses (Chen et al., 2000; Stuck et al., 2002). Written plans developed jointly with the patient and containing clear goals are characteristic of care coordination initiatives that achieve reductions in hospital care and medical costs (Chen et al., 2000). Moreover, research has shown that people vary in their expression of the need for psychosocial support and in the types of support they prefer.

For these reasons, the committee believes that planning for the delivery of psychosocial health services is a logical step in meeting the need for such services. Advance planning is likely to facilitate the identification and implementation of interventions best suited to each patient’s individual situation and to conserve resources not useful to the patient. Such planning for psychosocial health services should address mechanisms needed to effectively (1) link the patient with the needed services, (2) support the patient in managing his or her illness and its consequences, and (3) coordinate psychosocial and biomedical health care.

TABLE 4-2 Comparison of Needs Assessment Instruments (Wen and Gustafson, 2004)

|

Instrument |

Purpose and Administration |

Items and Domains |

Question Format |

Conceptual and Measurement Model |

|

Patient General |

||||

|

CARES (Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System) |

Find how cancer affects psychosocial, physical and behaviors |

93–132 items; 6 domains: physical, psychological, medical interaction, marital, sexual, miscellaneous |

Five-point scale plus “do you want help (yes/no)?” |

Competency-based model of coping |

|

Patient completes |

||||

|

CARES-SF (Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System-Short Form) |

Shortens the CARES for use with clinical trials |

38–57 items; 5 domains: physical, psychological, medical interaction, marital, sexual |

Five-point scale plus “do you want help (yes/no)?” |

|

|

Patient completes |

|

|||

|

CPNS (Cancer Patient Need Survey) |

Measures the importance of needs and the degree to which their needs are met |

51 items; 5 domains: coping, help, information, work, and cancer shock |

“Importance”: seven-point Likert scale; “how well met”: seven-point Likert scale |

|

|

Patient completes |

|

|||

|

CPNQ (Cancer Patient Need Questionnaire) |

Assesses unmet needs of people with cancer |

71 items; 5 domains: psychological needs, health info, ADLs, patient care/support, interpersonal communication |

Five-point scale: “what is your level of need for help?” |

|

|

Patient completes |

|

|||

|

Validity |

Reliability |

Responsiveness |

Burden |

||

|

Content Validity |

Construct Validity |

Internal Consistency |

Reproducibility |

||

|

Patient General |

|||||

|

Literature; Interviews with patients and family; Expert review |

Correlated with SCL-90, KPS, DAS; Good agreement with interviewers. |

Domains α ranged from .88–.92 |

Subscales: r=.84–.95 87% agreement n=71, time=1 week |

|

Time: 10–45 min; Reading level N/A; Acceptability: most found it easy to use |

|

Selected from the CARES by experts |

Correlated well with CARES, FLIC, KPS, DAS; Large sample sizes |

Domains α ranged from .60–.84 |

Dimensions: r=.69–.92 81%–86% agreement n=120, time=10 days |

Find physical, psychosocial change with time Correlated with FLIC @ 1, 7, 14 mo post-diagnosis |

Time N/A; Reading level N/A; Acceptable N/A |

|

Interviews with nurses, patients, and caregivers using Objective Content Test and Q-sort method |

|

Overall: 0.91 Importance: .83–.93 How well met: .79–.95 Domain: α=.88–.92 |

|

|

Time: 2–45 min; Reading level N/A; Acceptability: reported no problems when used |

|

Literature; Interviews; Expert review; Pilot test |

Discriminant validity: able to distinguish patients with different disease stages |

Domains α ranged from .78–.90 |

Intercorrelation all significant kappa >.4 n=124, time=10–14 days |

|

Time: 20 min; Reading level: 4th or 5th grade; Acceptability: 25% non-completion rate |

|

Instrument |

Purpose and Administration |

Items and Domains |

Question Format |

Conceptual and Measurement Model |

|

SCNS (Supportive Care Needs Survey) |

Assesses impact of cancer on lives of cancer patients |

61 items; 5 domains: psychological needs, health information, physical/daily living needs, patient care and support, and sexuality |

Five-point scale: “what is your level of need for help?” |

Factor analysis |

|

Patient completes |

||||

|

HCS-PF (Home Care Study-Patient Form) |

Assesses attitudes of terminally and chronically ill patients toward medical care |

33 items; 2 domains Satisfaction with: care availability, care continuity, MD availability, MD competence, MD personality, MD communication, general satisfaction Preference: home care, decision-making |

Agreement with five-point Likert scale |

|

|

Interview; patient may be able to complete |

|

|||

|

NEQ (Need Evaluation Questionnaire) |

Assess needs of hospitalized cancer patients in clinical setting |

23 items; 3 domains: helps diagnosis/prognosis, exam/treatment, communication and relations |

Agreement with yes/no statement |

Factor analysis |

|

Patient completes |

||||

|

PNAT (Patient Needs Assessment Tool) |

Screen cancer patients for physical and psychological functioning problems |

16 items; 3 domains: physical, psychological, and social |

Five-item impairment scale for each area within domain |

|

|

Part of clinician interview |

|

|

Validity |

Reliability |

Responsiveness |

Burden |

||

|

Content Validity |

Construct Validity |

Internal Consistency |

Reproducibility |

||

|

Based on CPNQ; Expert review; Pilot test |

|

Domain α ranged from .87–.97 |

|

|

Time: 20 min; Reading level: 5th grade; Acceptability: patients found it understandable, 35% non-completion |

|

Based on scales by Zyranski and Ware; Pilot test |

Poor discriminant validity |

Domains α ranged from 0.10–0.75 |

|

|

Time: N/A; Reading level: N/A; Acceptability: N/A |

|

Interviews; Pilot tests |

|

Domains: α ranged from .69–.81 |

Cohen’s kappa ranged from .54–.94 |

|

Time: 5 min; Reading level N/A; Acceptability: 63% of patients OK; 24% incomplete; 3% missing data |

|

|

Time=1week |

|

|||

|

Literature; Clinical experience |

Physical domain correlates with KPS; Psychological with GAIS, BSI MPAS, BDI Social with ISEL |

Domains: α ranged from .85–.94 |

Interrater reliability: Friedman: .87, .76, .73; Spearman rank order: .59–.98 |

|

Time: 20–30 min.; Training level: low; Acceptablity: N/A |

|

Instrument |

Purpose and Administration |

Items and Domains |

Question Format |

Conceptual and Measurement Model |

|

PNI (Psychosocial Needs Inventory) |

Measure the unmet psychosocial needs of cancer patients and their caregivers |

48 items; 7 domains: related to health professionals, information needs, related to support networks, identify needs, emotional and spiritual, practical and childcare need |

Five-point “Importance” scale Five-point “Satisfaction” scale |

|

|

Patient and caregiver complete |

|

|||

|

PCNA (Prostate Cancer Needs Assessment) |

Measures the importance and unmet needs of men with prostate cancer |

135 items; 3 domains: information, support, and care delivery |

Ten-point “Importance” scale Ten-point “Extent Need Met” scale |

|

|

Patient completes |

|

|||

|

PINQ (Patient Information Need Questionnaire) |

Measures the information need among cancer patients for the improvement of clinical practice and research |

17 items; 2 domains: disease-oriented and information about access to help and solution |

Four-point scale |

Factor analysis; Similar structure was found across Hodgkins; breast cancer patients and over time |

|

Patient completes |

||||

|

DINA (The Derdiarian Informational Needs Assessment) |

Measures the informational needs of cancer patients |

144 items; 4 domains: disease, personal, family, and social relationship |

Check the need present and rate importance on 10-point scale |

Theory of information seeking; Needs and hierarchy of needs |

|

Interview |

|

Validity |

Reliability |

Responsiveness |

Burden |

||

|

Content Validity |

Construct Validity |

Internal Consistency |

Reproducibility |

||

|

Literature; Interviews; Focus group |

Discriminant validity: detected the differences among needs at four critical movements of cancer trajectory |

α >.7 for each of the first six domains |

|

|

Time: N/A; Read level: N/A; Acceptability: 59% non-response rate and the characteristic of the non-respondents was examined |

|

Literature; Interviews using Critical Incident Technique and Nominal Group; Expert review |

Correlated with overall satisfaction-with-care |

Agreement on classification by three researchers working independently |

R=.97 Time=2 weeks |

|

Time: 43 min; Reading level: 7th grade; Acceptability: 11% non-completion |

|

Literature; Interviews |

Correlated with RSC, State-Anxiety Inventory and MMPI D-scale |

Domains: α ranged from .88–.92; Inter-item correlation >0.2 |

|

Detected the changing needs of patients at three time points before and after first treatment |

Time: N/A; Reading level: N/A; Acceptability: reasons to refuse: not wanting to be reminded of their illness, feeling too old, etc. |

|

Expert review |

|

Domain: α exceeded 0.9 for all domains |

80%–100% agreement found using McNemar test time=15–20 min. |

Detected difference between control group and experimental group |

Time: N/A; reading level N/A; Acceptability: N/A |

|

Instrument |

Purpose and Administration |

Items and Domains |

Question Format |

Conceptual and Measurement Model |

|

INM (Information Needs Measure) |

Assess the priority of informational needs of cancer patients |

9 information categories |

Control preference scale; ranking of informational resources; prioritization of information needs |

Based on the theoretical framework of Derdiarian |

|

Patient completes |

||||

|

TINQ-BC (Toronto Informational Needs Questionnaire-Breast Cancer) |

Identify information needed by women with recent breast cancer diagnosis to deal with illness |

51 items; 5 domains: diagnosis, tests, treatments, physical, psychosocial |

Five-point “Importance” scale |

|

|

Patient completes |

|

|||

|

Stage Specific |

||||

|

PACA (Palliative Care Assessment) |

Assess effectiveness of hospital’s palliative care program |

12 items; 3 domains: symptom control, insight, and future placement |

Four-point scale, except five-point scale for insight |

|

|

Professional completes |

|

|||

|

Validity |

Reliability |

Responsiveness |

Burden |

||

|

Content Validity |

Construct Validity |

Internal Consistency |

Reproducibility |

||

|

Literature; Based on works by Derdiarian; Expert review |

|

Kendall zeta: .95–.99 Kendall coefficient of agreement: .20–.35 |

|

|

Time: N/A; Reading level: N/A; Acceptability: N/A |

|

Literature; Nurse opinions |

Correlated with the information scale of HOS |

Overall α=.97; Domains α ranged from .73–.93; Correlation of subscales to total scale: .38–.88 |

|

|

Time: 20 min; Reading level: N/A; Acceptability: OK |

|

Stage Specific |

|||||

|

Interviews of patients |

Symptom scores correlated with McCorkle symptom distress scale |

|

Kappa ranged from .44–1 |

Sensitivity to detected statistically significant intervention effects |

Time: few min.; Training level: N/A; Acceptability: N/A |

|

Instrument |

Purpose and Administration |

Items and Domains |

Question Format |

Conceptual and Measurement Model |

|

STAS (Support Team Assessment Schedule) |

Assess quality of palliative care of multidisciplinary cancer support teams |

17 items; 8 domains: pain/symptom control, insight, psychosocial, family needs, home services, planning affairs, support of other professionals, communication |

Five-point Likert scale |

|

|

Professional completes |

|

|||

|

NEST (The Needs Near the End-of-Life Care Screening Tool) |

Measure experiences of end-of-life patients and possibly assess impact of interventions |

135 items; 8 domains: patient-MD relations, social connection, caregiving need, psychological distress, spirituality, personal acceptance, have purpose, clinician communication |

Five-point Likert scale |

Frame for a good death; Factor analysis; Measurement invariance across sociodemographic strata; Item response theory on the short version |

|

Interview; patient completes if possible |

||||

|

Caregiver |

||||

|

FAMCARE |

Measure family satisfaction with advanced cancer care |

20 items; 4 domains: information giving, care availability, physical care, pain control, and 2 other items |

Five-point Likert “Satisfaction scale” |

|

|

Family completes |

|

|||

|

Validity |

Reliability |

Responsiveness |

Burden |

||

|

Content Validity |

Construct Validity |

Internal Consistency |

Reproducibility |

||

|

Literature; Clinical experience |

Correlated with patient and family score, Karnofsky score, Spitzer QOL index. Support team scores correlate with patient and family scores |

|

Interrater reliability: 90% agreement except predictability |

Detected improvement in palliative care |

Time: 2 min. for existing patients, 5 min. new patients; Training level: N/A; Acceptability: N/A |

|

|

Evaluated 2 palliative care support teams |

||||

|

Literature; Interviews and focus groups; Symptom items from other scales; Pilot tests; Expert review |

|

Domains: α ranged from 0.63–0.85 at baseline and 0.64–0.89 at follow up |

|

|

Time: N/A; Reading level N/A; Acceptability: 69.2% patients found interview helpful |

|

Caregiver |

|||||

|

Interviews; Family ranking of items; Q-sort |

Correlated with McCusker and with overall satisfaction with care questions |

Overall α: 0.93; Domains: α ranged from .61–.88 |

R=.92 n=23, time <23 hrs |

|

Time: 22 min; Reading level: N/A; Acceptability: N/A |

|

Instrument |

Purpose and Administration |

Items and Domains |

Question Format |

Conceptual and Measurement Model |

|

FIN (Family Inventory of Needs) |

Measure needs of cancer patient’s family and extent needs are met |

20 items, 1 domain |

Ten-point “importance” scale and met/unmet check |

Fulfillment theory; factor analysis |

|

Family completes |

||||

|

FIN-H (Family Inventory of Needs-Husbands) |

Measure information needs of husbands of women with breast cancer |

30 items; 5 domains: surgical care needs, communication with MD, family relations, diagnosis/treatment specifics, husband’s involvement |

Five-point “Importance” subscale and three-point “Need Met” subscale |

Factor analysis |

|

Husband completes |

||||

|

HCNS (Home Caregiver Need Survey) |

Measures the importance and satisfaction of the needs of caregivers |

90 items; 6 domains: information, household, patient care, personal, spiritual, and psychological |

Seven-point “Importance” subscale and seven-point “Satisfaction” subscale |

Lackey-Wingate model |

|

Caregiver completes |

||||

|

HCS-CF (Home Care Study-Caretaker Form) |

Assess attitude of terminally and chronically ill caretakers toward medical care of their patients |

42 items; 2 domains: Satisfaction with care: availability, continuity, MD availability, MD competence, MD personality, MD communication, general satisfaction Preference for: home care, decision making |

Agreement with five-point Likert scale |

|

|

Interview; patient may be able to complete |

|

|

Validity |

Reliability |

Responsiveness |

Burden |

||

|

Content Validity |

Construct Validity |

Internal Consistency |

Reproducibility |

||

|

Literature; Items from original Critical Care Family Needs Inventory; Family review |

Correlated with FAMCARE |

Overall α for “importance” scale: 0.83 |

|

|

Time: “short”; Reading level: N/A; Acceptability: N/A |

|

Based on FIN Pilot test |

|

Overall α ranged from .90–.93; 73%–87% of items: item-total correlation 0.4–0.7 |

Importance subscale: r=0.82, Need Met subscale: r=.79 time: <24 hrs |

|

Time: 16–30 min; Reading level: N/A; Acceptability: 12 husbands refused to complete |

|

Statements from patients and home caregivers; Expert evaluation; Pilot test |

Psychological, patient care, personal and household Domains correlated with KPSS |

Overall α: 0.93, 0.98; Domains: α ranged from .85–.97 |

|

Detected changing caregiver needs at 3 time points |

Time: 30 min; Reading: 5th grade level; Acceptability: caregivers OK |

|

Based on scales by Zyranski and Ware; Pilot test |

Good discriminant validity |

Domains: α ranged from .50–.85 |

|

|

Time: N/A; Reading level: N/A; Acceptability: N/A |

|

Instrument |

Purpose and Administration |

Items and Domains |

Question Format |

Conceptual and Measurement Model |

|

NSS (Need Satisfaction Scale) |

Assess the intensity and satisfaction of the needs of bereaved families |

9 items |

Five-point “Felt need” subscale and five-point “Met need” subscale |

|

|

Family completes |

|

|||

|

Relative |

||||

|

ISNQ (Information and Support Needs Questionnaire) |

Assess information and support needs of women who have primary relative with breast cancer |

29 items; 2 domains: information and support |

Four-point “Importance” subscale and Four-point “Need Met” subscale |

|

|

Self-complete |

|

|||

|

NOTE: This table is from “Needs Assessment for Cancer Patients and Their Families.” Kuang-Yi Wen and David H. Gustafson, Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2004, © 2004 Wen and Gustafson; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. The electronic version of it is an Open Access article: verbatim copying and redistribution of the article are permitted in all media for any purpose, provided this notice is preserved along with the article’s original URL: http://www.hqlo.com/content//pdf/1477-7525-2-11.pdf. |

||||

|

Validity |

Reliability |

Responsiveness |

Burden |

||

|

Content Validity |

Construct Validity |

Internal Consistency |

Reproducibility |

||

|

Literature; Expert review |

Unmet needs correlated with overall satisfaction with care |

Overall α: 0.84; “Felt need” subscale: 0.74; “Met need” subscale: 0.84 |

|

|

Time: 15 min; Reading level: N/A; Acceptability: N/A |

|

Relative |

|||||

|

Literature; Interviews |

|

Domains: α ranged from .92–.95 |

|

|

Time: 37 min; Reading level: “middle” class; Acceptability: “several” reported it didn’t apply |

TABLE 4-3 Comparison of Domain Item Distribution Across Needs Assessment Instruments (Wen and Gustafson, 2004)

|

PINQ |

DINA |

INM |

TINQ-BC |

PACA |

STAS |

NEST |

FAM CARE |

FIN |

FIN-H |

HCNS |

HCS-CF |

NSS |

ISNQ |

|

17 |

144 |

9 |

51 |

10 |

17 |

|

20 |

20 |

30 |

89 |

42 |

20 |

29 |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

|

3 |

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

• |

|

|

|

30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

• |

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

• |

1 |

|

|

|

• |

|

|

|

11 |

|

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

• |

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

• |

2 |

3 |

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

• |

|

|

|

|

• |

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

• |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

6 |

|

|

14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

18 |

|

9 |

• |

1 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

• |

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

• |

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Open Access article: verbatim copying and redistribution of the article are permitted in all media for any purpose, provided this notice is preserved along with the article’s original URL: http://www.hqlo.com/content//pdf/1477-7525-2-11.pdf. |

|||||||||||||

Linking Patients to Psychosocial Health Services

Several mechanisms used to link patients with psychosocial health services delivered by health and human service providers have empirical support, although the strength of this support varies. These mechanisms include structured referral arrangements and formal agreements with external providers, case management, and collocation and clinical integration of services. Use of care/system navigators is also being studied for its effectiveness in linking patients with needed services.

Structured Referral

Although referral to other organizational or individual providers is a common mechanism for linking individuals with psychosocial health services (see the models in Table 4-1, examples in Chapter 5, and services delivered by referred organizations in Tables 3-2 and 3-3 in Chapter 3), there has been little study of the general effectiveness of such referrals. Most studies of referral have addressed referrals between physicians. These and one Australian study of referrals of cancer patients to psychosocial services indicate high rates of failure to connect individuals to the referred providers, frequent failure of the referred individuals to accept the referred services, and failure to track the outcomes of referrals (Bickell and Young, 2001; Curry et al., 2002; Grimshaw et al., 2006). These findings are consistent with the low ranking accorded referral by others studying practices aimed at achieving care coordination (Friedmann et al., 2000) and the finding of low success of referral by itself in linking cancer patients to needed psychosocial health services in one study of health maintenance organizations (HMOs) (Eakin and Strycker, 2001). And oncology nurses participating in focus groups pertaining to the implementation of survivorship care plans stated that they do not typically have formalized mechanisms for making referrals to social work services (IOM, 2007). On the other hand, the high utilization of services provided by such organizations as the American Cancer Society (which do not themselves provide medical services and thus depend in part on referrals for their clients) indicates that referrals can successfully link patients to needed services.

The few studies of how to make referrals more effective in linking patients with needed services have addressed referrals from primary to specialty care. The results of these studies indicate that using structured referral forms and educating referrers are most likely to improve the referral process (Grimshaw et al., 2006). Having formal agreements in place with those to whom referrals are made can also help (Friedmann et al., 2000). Tracking or following up on the actual receipt of referred services in cancer care is also recommended (Bickell and Young, 2001; Curry et al., 2002).

Referring patients to external providers is likely to continue to be a

primary mechanism for linking patients with needed psychosocial health services because it requires fewer organizational and physical plant resources than offering all psychosocial services on site. To conserve both psychosocial health services and the personnel and resources needed to make referrals, however, it is important for providers to implement approaches for doing so efficiently and effectively. This is an area that would benefit from further study.

Case Management13