3

U.S. Government-Wide Biological Threat Reduction Programs and Interagency Coordination

The Biological Threat Reduction Program (BTRP) of the Department of Defense (DOD) that has been discussed in Chapter 2 is one of a group of U.S. government efforts aimed at limiting the proliferation of expertise, materials, facilities, and technologies that could be used in development of biological weapons. Nonproliferation programs are also carried out by the Departments of State (DOS), Health and Human Services (DHHS), Agriculture (USDA), and Energy (DOE), and by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). DOS receives from Congress the funds for DHHS, USDA, and EPA and passes them through to these organizations. The important role of interagency coordination is underscored in Box 3-1.

|

BOX 3-1 Importance of an Interagency Approach “Nonproliferation engagement should be a multi-tiered, multi-agency, multi-sectoral, shared mission overseen by active National Security Council and White House leadership and regularly coordinated domestically and implemented internationally.” Former manager of a U.S. government biological nonproliferation program, July 2007. |

As discussed in this and other chapters, a number of factors that can lead to program success should be considered across the government in a consistent manner in developing programs. These factors include the approach in setting priorities, the review and selection process for individual projects, the approach to reviewing program progress, the process in selection of project participants, the importance of communications among departments and agencies, and the integrity of personal relationships that are established with foreign partners. At the same time, weaknesses in interagency coordination efforts are a special concern.

Table 3-1 indicates the distribution of Fiscal Year (FY) 2006 and 2007 nonproliferation program funds among the responsible U.S. government organizations. While BTRP received a considerable increase in funding for 2007, as discussed in Chapter 2, the funding for other departments declined.

TABLE 3-1 Distribution of worldwide bio-related nonproliferation funds in FY 2006 and 2007 (estimated, in millions of U.S. dollars rounded to the nearest $0.1 million).

|

Program |

FY 2006 |

FY 2007 |

|

DOD Biological Threat Reduction Programa |

|

|

|

$ 21.6 |

$ 15.5 |

|

$ 1.3 |

$ 0.5 |

|

$ 45.8 |

$ 48.7 |

|

$ 1.0 |

$ 6.1 |

|

DOS |

|

|

|

$ 0.7 |

$ 0.9 |

|

$ 10.0 |

$ 7.0 |

|

$ 3.9 |

$ 8.0 |

|

$ 15.1 |

$ 5.7 |

|

$ 7.6 |

$ 2.3 |

|

$ 6.0 |

$ 2.0 |

|

$ 1.5 |

$ 1.4 |

|

DOE: Global Initiative for Proliferation Prevention (GIPP) |

$ 3.6 |

$ 2.2 |

|

NOTES: For the Science and Technology Centers, figures cited include only U.S. party-funded projects in the biological sciences. They do not include costs of project management or workshops that may be funded through the general U.S. contribution to the Centers. The HHS/BTEP Bio-Chem numbers shown above reflect only U.S. side program costs. Unspent BTEP funds at ISTC need to be spent down (more than $10 million left over between FY 2005 and FY 2007). HHS/BTEP funds were reduced in FY 2007 to spend down those funds before additional funding for FSU program costs could be allocated. aThe DOD figures for FY 2007 do not include unallocated funds of $1.4 milllion and withheld funds of $ 0.2 million. b These funds are transferred to DHHS, USDA, and EPA, as listed on the lines below. Also, these funds provide some support for redirection of the activities of former chemical weapons specialists as well. SOURCE: Figures provided by DOD, DOS, and DOE in June and July 2007. |

||

Table 3-2 identifies activities of the different departments and agencies. The costs for supporting some activities such as dismantlement and facility upgrades are generally higher than costs for other activities such as training and research investigations. BTRP has supported many of the most expensive endeavors, which explains some of the differences in levels of funding that have been made available. But still, the difference in funding levels is striking. No other department has received financial support that compares to the support for BTRP.

TABLE 3-2 Examples of U.S. government nonproliferation activities.

There are substantial tangible and intangible benefits to U.S. national security from these nonproliferation programs. However, more attention should be given to documenting benefits. For example, specific scientific payoffs from cooperation should be available in making the case for joint research efforts. This chapter presents several examples of projects that have led to scientific and technical discoveries, as well as contributing more directly to reducing specific security concerns.

Unfortunately, there are no systematic mechanisms for linking results of individual non-proliferation projects to the U.S. government’s broader interests in the biological sciences and biotechnology. Greater attention should be given to enhancing the flow of new science and technology achievements attributable to BTRP and related programs into other U.S.-funded activities. Such a step will help set the stage for establishing sustainable partnerships between researchers in other countries and the broad U.S. government-supported research community.

Program Overviews and Future Directions

The program of each department has a nonproliferation objective. However, the selection and design of individual projects are greatly influenced both by staff expertise and experience and by international programs carried out by the departments that have been called for under other Congressional mandates. This departmental orientation is of particular importance in selecting diseases that are of interest and in orienting international activities to complement domestic research programs that are under way in the United States.

Department of State

DOS is responsible for four programs that address global biological threats. Several different legislative authorities govern these programs, thereby providing the department with

considerable implementation flexibility.1 All programs share a nonproliferation mission, but they approach this task in different ways.

In 2006, more than one-half of the budget of the Cooperative Threat Reduction Office of the Bureau of International Nonproliferation of DOS (ISN/CTR) was applied to biothreat projects in the former Soviet Union. However, declining overall budgets within DOS for cooperative threat reduction activities and expanding program responsibilities will likely result in reduced DOS-funded activity for biology-oriented projects in the region in FY 2007 and beyond. This trend will affect DOS projects implemented directly through the Science and Technology Centers (STCs) that are discussed below and programs funded from the department’s budget and carried out by DHHS, USDA, and EPA. It also may affect DOD/BTRP’s ability to implement certain aspects of its program that are dependent on support by the STCs.

-

Science and Technology Centers (International Science and Technology Center-Moscow [ISTC]; Science and Technology Center in Ukraine-Kyiv [STCU]): The two STCs are multilateral organizations that share a broad mandate to redirect former Soviet weapons scientists, engineers, and technicians to sustainable non-military activities. DOS projects carried out through the STCs include substantial funding to counter biological threats. In addition to being a mechanism for developing and funding projects, the STCs serve other functions that have evolved over the years (for example, advice on intellectual property rights, training seminars, and international conferences). They would be difficult to replace as a nonproliferation program implementation tool or even as a mechanism for facilitating international scientific collaboration.

However, the ISTC has experienced a number of administrative obstacles in recent years, in large measure due to Russian government actions and at times inaction. Long-standing issues involve problems concerning the hiring and rotation of Russian staff, disputes over the tax exempt status of the ISTC, and disagreements over the reimbursement to the ISTC by the Russian government of value-added taxes that should not have been collected from project budgets in the first place. At the same time, Russia has not completed the internal procedures necessary for the entry into force of the intergovernmental agreement establishing the ISTC, specifically ratification of the agreement by the Duma. As a result, the ISTC has had only temporary legal status for the past 13 years. The U.S. and other participating governments are well aware of these difficulties and are attempting to improve Russian government support for the ISTC.

-

Bio-Industry Initiative: The Bio-Industry Initiative (BII) was established in the wake of 9/11. It combines nonproliferation and counterterrorism approaches to reduce terrorist access to biological weapons, facilities, and expertise. More broadly, it joins the United States with Russia to combat bioterrorism by (1) transforming former biological weapons production facilities, their technology, and their expertise for sustainable, commercial applications, and (2) accelerating drug and vaccine production through research and development partnerships between U.S. and Russian scientists that address infectious and communicable diseases prevalent in the former Soviet Union and other regions.

BII has been designed to be flexible and responsive to interests of foreign partners. The program works directly with individuals and institutes, through the STCs, and through other organizations to implement its projects. It plans to continue to operate in Russia and other countries of the former Soviet Union, although with significantly reduced funding. BII has a

-

good reputation in the United States and abroad for effective program design and implementation, and some of its approaches deserve consideration as global models for related efforts within other programs (for example, see Box 3-2 for an interesting approach).

|

BOX 3-2 BII Support of Facility Redirection BII is helping to reconfigure the Berdsk Biological Preparations Plant, a large-scale fermentation plant in Russia, into peaceful commercial activities. The now privately-owned facility produces industrial enzymes and animal feed additives. BII is providing support to optimize commercial production and to improve the enzyme manufacturing with the goal of sustainable employment for 180 former weapon scientists. SOURCE: Information provided by DOS, May 2007. |

-

Biological-Chemical Redirection Program (BCR): This program provides funding to USDA, DHHS, and EPA for programs listed separately below: As the U.S. government focused on redirection of former Soviet biological weapons expertise in the late 1990s, DOS quickly recognized that knowledgeable experts with skills necessary for program implementation and oversight resided in a number of other U.S. government departments and agencies. Therefore, DOS worked with the Congress to augment its legislative authorities, which now allow DOS to include expertise from other U.S. government departments and agencies in biological threat reduction efforts and to provide funding for their program activities. This expanded authority led to programs carried out by DHHS, USDA, and EPA. Each of these organizations receives annual fund transfers from DOS as discussed below.

-

Global Biosecurity Engagement Program (BEP): In 2006, the National Security Council (NSC) tasked ISN/CTR to draft a strategy for strengthening global pathogen security. The effort identified potential proliferation problems in critical geographical areas. The strategy, as approved by the NSC, identified roles for U.S. government departments and agencies and assigned the lead engagement effort to ISN/CTR. At the time, other departments and agencies, such as DOD, DHHS, and USDA, lacked either the requisite funding, the legislative authority, or both, to assume the lead. In some ways, the NSC strategy mirrors a related strategy dealing with homeland security that links reduction of biological threats to improving threat awareness, developing prevention and protection tools, enhancing surveillance and detection, and developing response and recovery capabilities.2

BEP’s objective is to promote legitimate bioscience research while recognizing the confluence of bioterrorism threats, emerging infectious diseases, and the rapid expansion of biotechnology. BEP’s initial focus areas are South Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East; and programs emphasize ensuring the physical security of pathogens, upgrading laboratory biosafety procedures, and improving approaches for combating infectious diseases. Pilot efforts in Indonesia and the Philippines include conducting risk assessments; developing country-level strategies for bilateral engagement on laboratory biosafety, biosecurity, disease surveillance, and

|

2 |

See National Security Policy Directive 33, Biodefense for the 21st Century, signed June 12, 2002. Available on-line at http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2004/04/20040428-6.html. Accessed May 30, 2007. |

-

diagnostics; and developing a grants assistance program to promote meaningful research collaborations involving U.S. and local institutions.

-

Planned future activities include engaging Japan on ways to minimize biological threats, developing Asian biosecurity standards, engaging Egypt on threat reduction, continuing workshops and related activities in Thailand and Malaysia, and conducting preliminary discussions with Pakistan and Yemen.

Department of Health and Human Services

The Biotechnology Engagement Program (BTEP) of DHHS operates in the former Soviet Union with the following three mandates developed by DHHS in consultation with other government departments:

-

Discourage the proliferation of weapons-related expertise and engage former biological and chemical defense scientists in civilian-oriented research

-

Apply scientific expertise toward urgent public health needs in the region, thereby advancing public health policy via evidence-based science

-

Promote Western scientific practices and strong international cooperation, provide experience that will enable successful pursuit of competitive research funding, and promote commercialization of technology developed in projects

BTEP had 33 active projects in Russia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Armenia as of February 2007. It had completed an additional 29 projects and had 14 projects under development. Projects focus on dangerous and emerging infectious disease, endemic health problems and vector-borne diseases. Of the 62 active and completed projects, nearly one-half have addressed tuberculosis or HIV/AIDS.

BTEP has played a particularly important role in working with BTRP to support cooperative research with Russian specialists on development of medical countermeasures to smallpox during the past few years. These projects, carried out at the Institute for Virology and Applied Biotechnology (VECTOR), have provided scientific results of considerable interest while also developing U.S. partnerships with important Russian investigators who have unique experience in addressing this highly dangerous disease that is one of the world’s most feared agents of bioterrorism. While the future of bilateral collaboration in this field is uncertain, the connections that have been developed between American and Russian scientists should continue to provide important international windows into highly sensitive activities in Russia.

Unfortunately, only one full-time mid-level Public Health Service Officer is currently assigned to program management and implementation within DHHS after a decade of assignment of stronger and more empowered staff resources to the program. BTEP works through the STCs and uses a commercial contractor to assist with proposal development, monitoring and evaluation of projects, program and logistical support, and procurement of supplies and material. U.S. collaborating partners on BTEP projects are responsible for technical and financial review of the projects and for approving requests for project changes.3

For the future, DOS has asked BTEP to enhance its engagement of former chemical weapons scientists, which could erode its focus on biological scientists. At the same time, BTEP plans to develop regional, cross-border biology projects in the former Soviet Union. Also, it plans to initiate additional activities in countries that are linked to the STCU.4

Department of Agriculture/Agricultural Research Service (USDA/ARS)

USDA began its Scientific Cooperation Program in the former Soviet Union in 1998 with funding from DOS. Built on a strong existing base of ARS global activity, the program had 55 projects active as of February 2007, with 16 additional projects already completed and 17 more under development.5 The program supports projects in Russia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan with the following objectives:

-

Reduce the threat of chemical and biological weapons development and deployment

-

Advance agricultural science by supporting types of expertise of particular importance in the region

-

Enhance the effectiveness and productivity of ARS research programs

-

Improve Eurasian economies through advances in agricultural technology

Projects focus on the three broad areas of animal health and production, natural resources, and crop health and production. Each project must have one or more U.S. collaborators from the USDA/ARS laboratory system. These ARS collaborators with the consistent support of ARS leadership are the cornerstones of the strong scientist-to-scientist collaborations that have made the USDA program a model that provides value to all parties at modest cost.

During 1998-2006, USDA/ARS received about $44 million in transfers of funds from DOS, but USDA’s FY 2007 budget has been significantly reduced from previous years to $2 million. Despite the funding decrease, USDA/ARS will continue with limited new initiatives. The program includes joint projects with BII to (1) support establishment of a pilot production plant in Russia for antibiotics, and (2) cooperate with veterinary institutes in Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.

As discussed in Chapter 2, international exchanges of strains of dangerous pathogens have become difficult to implement, regardless of the research rationale of validating research results in laboratories of both collaborators on specific projects. While USDA researchers may continue to seek agreement with partner ministries for such exchanges, they should consider arranging for joint analyses in the region, under appropriate laboratory conditions. This approach would avoid the time-consuming, and often fruitless, political and administrative discussions concerning strain exchanges.

|

BOX 3-3 USDA Addresses Avian Influenza “An aspect of the collaboration is getting a handle on the basic ecology of avian influenza…. Russia is crossed by two major migratory flyways…. The collaborative group has found that some avian influenza variants not previously found in Russia were isolated during this project. Data also suggest that one variant, H4N6, has expanded its host range and that aquatic mammals, mainly muskrats, are involved in maintenance of the virus in nature.” SOURCE: Durham, S. 2005. International partnership for poultry safety. Agricultural Research 53(11):9-11. Available on-line at http://www.ars.usda.gov/is/AR/archive/nov05/poultry1105.htm. Accessed July 24, 2007. |

Environmental Protection Agency

EPA’s program is the smallest of the DOS-funded programs. EPA responds to important environmental protection and remediation problems and has carried out more than 20 projects. The agency’s Office of International Affairs provides overall program and financial management, and its Office of Research and Development provides scientific and technical experts for individual projects.

As one example of its activities, EPA has played an important role in supporting the development and implementation of environmental assessments in Kazakhstan. Of particular interest have been the activities of a former biological weapons laboratory in Stepnogorsk to develop new nature preserve areas where there are environmental health problems that require isolation from the general public.

Department of Energy

Since 2003, DOE’s total funding for biothreat projects has been more than $23 million. Of the available program funds for all types of redirection projects in the former Soviet Union, approximately 20 percent has been devoted to engaging biological institutes.

The Initiative for Proliferation Prevention (IPP), DOE’s most relevant program, has the objective of engaging in peaceful and sustainable commercial pursuits former Soviet scientists, engineers, and technicians who had been involved with weapons of mass destruction. This program is implemented through cooperative projects involving former Soviet weapons specialists, DOE’s national laboratories, and U.S. industry. IPP is designed to identify non-military, commercial applications for former Soviet technologies, with the aim of providing new technology sources and markets for U.S. companies, while creating commercial opportunities and income for former Soviet weapon specialists.

IPP has funded biology-related projects with institutes in Russia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Ukraine, Armenia, and Georgia. More than 90 percent of these projects have been in Russia. In 2005, IPP’s boundaries of activities were extended to other parts of the world, including Iraq.

One example of a successful IPP project has been the development of microbes that can assist in oil pollution bioremediation. The Russian partner has isolated four strains of

microorganisms with high efficiencies for remediation of surface water and selected soils. Field trials indicate microbial persistence in soil with continuous hydrocarbon degradation. According to DOE, this approach should allow re-vegetation in one to three years, depending on the climate.

IPP’s activities complement other DOE biothreat prevention programs. These programs include training in international export control procedures such as identification of sensitive biology-related commodities; support of the interagency working group and the U.S. delegation responsible for the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BWC); improvement of physical protection of biological materials in laboratories in Indonesia; and conduct of biosecurity workshops in India, Jordan, and Pakistan. These activities are carried out under DOE’s Global Security and Engagement Program.

It is likely that future IPP projects will continue to engage biological institutes in the states of the former Soviet Union, predominately in Russia. Although the funding levels and numbers of projects will depend on the merits of individual projects, DOE anticipates that biology projects will continue to command 15 to 20 percent of the total available funding for redirection activities. Areas of interest will probably continue to center on the technologies involved in bioremediation, decontamination, biological detectors, and crop protection products.

Interagency Coordination

The Nonproliferation Interagency Roundtable (NPIR) was initially established to review research proposals to be carried out in the former Soviet Union (FSU) but not to coordinate nonproliferation activities across departments. While some coordination results from NPIR reviews, potential synergies between the agencies’ programs are not always recognized. Nonproliferation activities probably can be improved through better coordination as discussed below.

An Interagency Success Story

An early U.S. goal during the 1990s was to help former Soviet research facilities distance themselves from the Biopreparat organization, which served as a civilian umbrella organization for the Soviet biological weapons program. After a decade of engagement activities, that goal has largely been met, in part due to such engagement. In particular, two of the largest Biopreparat facilities that dealt respectively with viral and bacteriological pathogens—namely, the State Research Center for Virology and Biotechnology (VECTOR) and the State Research Center for Applied Microbiology—were transferred to the Ministry of Health and Social Development in 2006. The institutes’ missions are now oriented to focus exclusively on public health, with an emphasis on diseases endemic to Russia. The Russian government is providing greater budgetary resources to support activities directed to public health problems than was the case in the past. These transitions benefited significantly from U.S. government program support of the following activities:

-

Cooperative research (DOS [STCs, BII, BCR], DOD/BTRP, USDA/ARS, DHHS/BTEP, DOE/IPP)

-

Increased physical security (BTRP)

-

Training and certification on laboratory animal care and use (STCs, BII, BTRP)

-

Travel grants to attend professional association and scientific meetings (STCs, BII, USDA/ARS, DHHS/BTEP, BTRP)

-

Business and English language training (STCs, BII, BTEP)

-

Pursuit of business development opportunities (IPP, BII)

In short, a number of U.S. programs have supported these research facilities with projects to help facilitate the transition to public health and agriculture activities. The cooperation has led to unprecedented levels of access and transparency for program activities and financial audits and to long-term professional relationships that should help ensure future transparency. These successes demonstrate the payoff of coordinated action through multiple programs.

Improving Interagency Coordination

Overall guidance for program direction is promulgated by the NSC, as noted above. This guidance is reviewed periodically by the NSC and updated as appropriate. An important element of this guidance is project review and coordination which has been carried out through the NPIR. This process has allowed the interested departments and agencies to review each other’s proposed projects with particular attention to potential dual-use risks and to nonproliferation benefits while reducing unnecessary duplication of effort.

In general, the NPIR process appears to function well. The effectiveness of the DOS-led monthly interagency meetings, which include representatives of BTRP, was reviewed by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) in 2005 as well as in earlier years. GAO observed that biological redirection programs have “clearly delineated roles and responsibilities, regular interaction, and dispute resolution procedures.”6 The report goes on to say that the agencies implementing programs reported no coordination difficulties and that the NSC guidelines and regular information sharing ensure that the departments and agencies are aware of each other’s program activities and help avoid duplication of efforts. The interagency process also benefits from department-level internal scientific and policy reviews that feed into the interagency process.

In addition to serving as a platform for project review and information exchange, the NPIR process has been used by the NSC as a venue for developing strategies and program approaches that apply across programs. At times coordinated strategies for regions, countries, and even specific institutes have been developed, but this has not been systematic. A current weakness of these strategies is that they encompass only nonproliferation programs. They do not reach out to broader departmental, national, or international activities. There does not seem to be sufficient interest at senior official levels to integrate nonproliferation programs with related programs that address other objectives. For example, the link between the DHHS/BTEP projects on multi-drug resistant tuberculosis and much larger DHHS efforts in this field is weak. Also, traditional foreign assistance activities in the fields of public health and agriculture are carried out on separate tracks from nonproliferation activities, even in the same countries.

A related coordination challenge, particularly with regard to BTRP, is the development of parallel country strategies by different programs. As discussed in Chapter 2, BTRP is preparing country science plans. These plans focus on BTRP and partner government interests, and they set

|

6 |

U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2005. Weapons of mass destruction: nonproliferation programs need better integration. GAO-05-157. Available on-line at http://www.gao.gov/cgi-bin/getrpt?GAO-05-157. Accessed on May 30, 2007. |

forth in considerable detail BTRP’s planned activities in each country. At the same time, they do not give adequate attention to the interests of other U.S. government departments and agencies that may intersect with BTRP interests in specific countries. Still, BTRP should be commended for its initiative and encouraged to seek broader coordination.

Given funding uncertainties, the different interests of different departments, and the importance of adjusting priorities quickly when problems emerge, a unified plan for each country does not seem realistic. Of course, there should be good information exchange to promote complementarity when possible. An annual interagency report that would be publicly available describing programs and achievements would provide a good background mosaic for a number of organizations interested in supporting related programs. At present, some agencies prepare regular reports to support budget submissions, and this effort could be part of the basis for an interagency effort that would standardize program data in such annual reports.

The 2006 strategy requested by the NSC for “global” biosecurity engagement is intended to apply to all departments and agencies and foresees a number of activities in biosafety and biosecurity with an initial focus in Southeast and South Asia. DOS is proceeding to implement programs, working in some cases with experts from other agencies. DOS efforts to promote consolidations of strain collections, increase physical security at biological facilities, and improve disease surveillance mirror BTRP programs, but they are being undertaken thus far without BTRP participation. BTRP has not been tasked to expand into these regions although it has resources and experience that should be helpful. Congress may earmark BTRP funds for use outside the FSU, which will require greater attention to the most effective use of BTRP as well as capabilities of related programs in other countries.

As previously noted, BTRP receives by far the largest share of funding available to the departments and agencies for biological threat reduction activities, and BTRP’s proportion of the overall budgets for cooperative threat reduction funding is increasing. However, BTRP’s success in addressing the threats depends in part on scientific and technical expertise that is available in other departments and agencies such as DHHS, USDA, and EPA, which in turn may depend on DOS funds and limited internal budget allocations. If the non-BTRP programs do not receive funding to carry out their parts of integrated programs, there are of course broader implementation difficulties. An important approach is a BTRP budget strategy that includes other departments working in close coordination with BTRP to carry out key components of interagency programs. In this regard, BTRP is aware of the importance of drawing on the expertise of other departments. It has consistently provided substantial resources to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to assist with specific tasks and is currently attempting to arrange for support by USDA/ARS using BTRP funds. Also, as previously mentioned, BTRP cost shares with DHHS support of smallpox-related research in Russia. But, as suggested in Chapter 2, an amendment to BTRP’s authorizing legislation could call on BTRP to use the expertise of DHHS and USDA to the fullest extent that is practical and to provide financial support to these departments for facilitating joint activities.

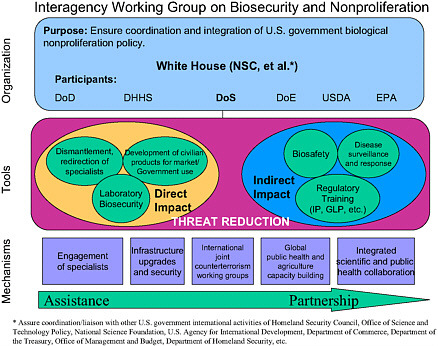

Proposed Model for Interagency Coordination

Given the geographical expansion of biological threat reduction programs already under way and the need to maximize program impacts, a new model of U.S. government interagency coordination to promote synergies and reduce duplication may be needed. One approach would

call for an NSC-led Interagency Working Group on Biosecurity and Nonproliferation, with senior agency officials as participants. The Working Group would help ensure coordination and integration across U.S. government programs, including global health security, biosafety, and nonproliferation efforts. Participants would be drawn from DOS, DOD, DHHS, USDA, DOE, and EPA, with support from the intelligence community and inputs from other departments with relevant international programs.

Such a structure could help match interagency policy-driven objectives to program implementation mechanisms and capabilities across a spectrum of activities ranging from initial engagement of former weapons specialists to broadly based scientific collaboration. The U.S.-Japan Cooperative Medical Sciences Program, which has operated since 1965, offers important lessons in this regard, particularly the mutual benefits from sustained research engagement on a wide variety of research issues. Developing broad program approaches could facilitate better tracking of interactions of direct impact programs, such as biosecurity, on other broad objectives including, for example, increased disease surveillance. Figure 3-1 suggests an expanded model of the current interagency approach.

FIGURE 3-1 Integrating U.S. government nonproliferation efforts.

Whatever the model, the White House should exert strong leadership to ensure integration of BTRP with related biological threat reduction activities supported by the U.S. government. The key is the involvement in policy formulation of senior officials from all of the principal departments and agencies who collectively can ensure sustained, high-level attention to international biological risk reduction throughout the government. These officials

should be in a good position to develop common government-wide strategic goals to help guide BTRP and related on-the-ground programs supported by the U.S. government and to assess the cumulative security and health impacts of programs of different departments.

Lessons Learned from Department and Agency Experiences

The experiences of the departments and agencies that have been engaged in biological threat reduction programs are substantial. Set forth below are a few of the key lessons that have been learned in recent years based on observations of the NRC committee.

-

There can be significant value to strategy-driven, coordinated efforts within the U.S. government and with other international partners. The number of inter-related program activities supported by the U.S. government is large, let alone relevant programs supported by others. A strategic framework that helps guide individual programs could be very useful. Time is too short and funding is too limited not to take advantage of the insights and achievements of other organizations and agencies. Almost every important biological facility in the former Soviet Union now has multiple international funders, and the need for coordination seems obvious.

-

High quality U.S. and other collaborators are a key to success. No longer is the objective simply to provide opportunities for non-threatening research by former weapon specialists. The objective should be to support activities that will command sustained support in the future due to the contributions of local activities to public health, agriculture, and international science. Experienced collaborators who recognize the scientific importance of well-designed programs and can ensure that they meet international standards are essential in setting the stage for sustainability of complicated biological activities.

-

A larger segment of the American academic community should become involved in nonproliferation programs. Most government departments and agencies have relied primarily on their own specialists to provide advice on appropriate approaches to engagement and to serve as collaborators on projects. Greater efforts are needed to engage a larger segment of the American academic community with relevant expertise and with the interest to remain engaged with foreign counterparts over the long term. BTRP’s attempt to have a consortium of universities that could recruit scientists for overseas assignments has not worked very well. Most of the participants were not well embedded in American universities or research centers but were simply taking on overseas assignments as temporary career moves with little likelihood of continued engagement through the university consortia after one- or two-year stints abroad.

Consideration should be given to establishing a global competitive grants program funded and administered on an interagency basis to encourage American academics to become engaged in international biological programs with important nonproliferation benefits. Project development grants could facilitate initial scientist-to-scientist contacts. Larger grants could subsequently support joint projects that have been developed. Open competitions should help ensure that important projects and well-qualified investigators are chosen.

-

Program priorities should respond to threat assessments that take into account both individuals and facilities. Assessments of all biological assets that could be of interest to hostile groups should be carried out. Usually, the experience and reliability of human resources at the facility level are an important concern, and programs should be highly selective to ensure that key specialists, as well as key facilities, are appropriately involved in engagement activities. Because of the pervasive nature of biotechnology and its high degree of dual-use application, in

-

some cases, programs should include specialists who have never had any connection to biological weapons programs.

-

Projects that link a strong foreign institute in the lead working with one or more secondary institutes help create networks and provide project mentoring for less experienced institutes. Networking was not a strength of the scientific community within the former Soviet Union. In security-related areas in particular, institutes were deliberately separated. However, in the modern world of science, networking is essential. While it has become commonplace for strong institutes to reach out to international partners, much greater effort is needed by these institutes to work with other institutions locally to help strengthen the overall infrastructure of the countries, and BTRP should support such activities.

High-level leadership within participating U.S departments and agencies is essential. Ensuring biosecurity requires a long-term commitment that will only be sustained if the leadership within the participating departments and agencies recognizes the importance of global engagement and gives nonproliferation activity a high priority. One reason for the high degree of effectiveness of the USDA efforts stems from the strong support it has received at senior levels. The result has been a strong integration of the program into the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) infrastructure with the program designed to have clear benefit to USDA and ARS. It does not detract from, but indeed supports, the domestic mission while serving a broad nonproliferation mission.

High-level international support is also critical. A “cooperative” approach is an essential aspect of threat reduction. Without the active support of the government or governments on whose territory projects are carried out, lasting impact is unlikely. For these programs to have significant nonproliferation benefit, they must be sustainable into the future. With improving economic profiles in some countries, particularly Russia, the host government must in time assume the burden for sustaining activity into the future, and particularly a commitment to appropriate levels of training, certification, and standards. The goal of the U.S government should be to establish long-term self-sustaining collaborations in biotechnology and the health and agriculture sciences.

In summary, the growing contributions of the life sciences to improving the lives of people throughout the world together with the relative ease of developing biological materials that can cause immeasurable harm and disruption to these same populations are strong reasons for the U.S. government to accord a high priority to promoting appropriate use of dual-use biological technologies. The responsibility and capability for achieving this objective are shared by a number of U.S. government departments and agencies. These departments have good track records in using nonproliferation funds to direct biological assets of countries in political transitions to useful scientific endeavors. Partner governments, private firms, charitable foundations, research institutes, and universities have resources of critical importance as well. BTRP is by far the largest U.S. government engagement program dedicated to countering international biological terrorism that could impact on the United States; therefore this program is especially well suited to catalyze and leverage the vast, high-quality educational, scientific, and entrepreneurial resources of the nation in the struggle with bioterrorism.