Programs to Stimulate Startups and Entrepreneurship in Japan: Experiences and Lessons

Takehiko Yasuda

Toyo University and Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI)

1.

THE DECLINE OF STARTUP RATE AND THE CHANGE IN POLICIES TO STIMULATE STARTUP IN JAPAN

During Japan’s high-growth era that lasted through the 1970s, startup firms maintained a high entry rate. However, based on some statistic data, the entry rate fell in the 1970s-1980s, indicating the stagnant entrepreneurship activity in Japan. Concerned that this decline in new business activity might weaken the nation’s economy, the government began in 2000 to institute policy measures designed to stimulate formation of new companies.

This chapter provides a preliminary assessment of how these policies have affected startups and small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

The Japanese government first became aware of the reversal of the rate of entry and exit in 1989, which was reported in the “White Paper on Small and Medium Enterprises in Japan.” Although the paper warned that the slowdown in startup formation could lead to economic stagnation, it took a long time for this recognition to lead to actual policy changes. It was only after the revision of the Small and Medium Enterprise Basic Law in 1999 that the Japanese government began to address the entrepreneurial challenge. The reason for this 10-year interval between the recognition and the action is, in my view, due to the irreconcilability of the policies needed to promote startup activity with the existing SME policies. Until the 1990s, the Small and Medium Enterprise Basic Law (hereafter referred

to as the “Old Law”) enacted in 1963 guided the policies for small and medium enterprises in Japan. The Old Law intended to correct the “dual structure” in which small and medium companies trailed behind their large counterparts in wage and labor productivity. If SMEs could not match the performance of large companies, it was not desirable to encourage the creation of more SMEs.1 However, the situation changed in the 1990s when the government recognized that in England and the United States startup companies had provided a valuable stimulus to the economy since the 1980s. Therefore, in 1999 the Japanese government revised considerably the Small and Medium Enterprise Basic Law. This “New Law” aimed to promote diverse and vigorous growth of independent SMEs.2 After this turning point, government took a series of steps to promote startups.3 The Japanese government’s 2001 “Startup-Doubling Plan” has as its target a doubling of startups from 180,000 in 2001 to 360,000 by the year 2006.

2.

THE MAIN POLICIES TO PROMOTE ENTREPRENEURSHIP ACTIVITY IN JAPAN

The primary policies to support startup companies are (1) removal of the minimum capital requirement for the establishment of limited liability companies, (2) provision of education and information for entrepreneurs through the National Startup and Venture Forum, and (3) a new startup loan program through the National Life Finance Corporation, which requires no collateral, guarantors, or personal guarantees, and the expansion of the upper limit of “free property” based on the New Bankruptcy Law.4

Removal of Minimum Capital Regulation

Removal of the minimum capital requirement for limited liability companies was conditionally executed in February 2004 by way of revision of the Law for

Facilitating the Creation of New Business. This measure was adopted because the minimum capital requirement for limited liability companies was often a constraint for startups, which typically have only a small amount of funding. Before the introduction of this policy, minimum capital requirement for joint-stock corporations was ¥10 million5 under the Commercial Law regulations. This new policy seems to be successful. Between February 1, 2004, and January 21, 2006, there were 24,639 confirmed applications with 20,211 notification completions. The corresponding numbers of the firms with ¥1 capital (the “¥1 company”) are 1,172 and 927 respectively.

Based on the success of this policy, the Japanese government enacted the Corporate Law in 2005 to remove the minimum capital requirement for establishing firms in general, which is consistent with the U.S. joint-stock corporation policy.

Provision of Education and Information to Entrepreneurs

According to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor6 research program, of its 46 subject countries, Japan is second to the lowest in entrepreneurship activity. In addition, according to the Employment Status Survey of the Ministry of Public Management, Home Affairs, Post and Telecommunications, there were 1.24 million would-be entrepreneurs in Japan in 1997, which means that for every 50 employed people only one would-be entrepreneur was found.7 Moreover, the survey also reports that only half of this class of would-be entrepreneurs is actually preparing to become self-employed.

Japanese leaders realized that an important first step would be to provide education and information about entrepreneurship to stimulate interest. In 1999, the Japan Productivity Center for Socio-Economic Development established the National Startup and Venture Forum, a nonprofit nongovernmental organization to provide services to attract and help entrepreneurs. Among its activities was the establishment of the Japan Venture Award to honor successful entrepreneurs and their sponsors that could serve as role models for the next generation of startups. It also created the Startup and Venture Evening Forum, which stages small symposia that focus on specific challenges facing entrepreneurs.8

Other organizations have joined forces on policies to promote the startup of new business. For example, the Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry and

Local Chamber of Commerce and Industry help potential entrepreneurs to complete concrete business strategies by holding “Startup Classes.”

Startup Loan Program

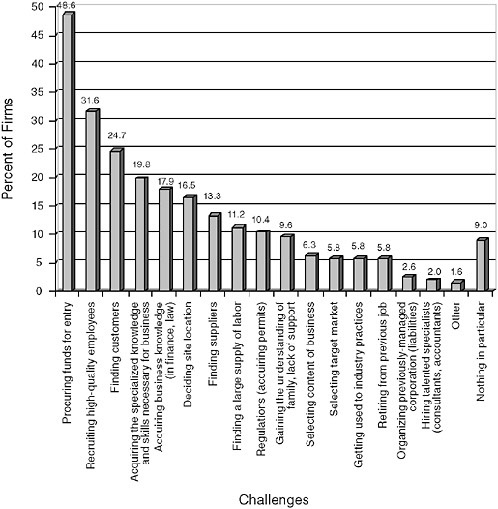

Research in the United States and Europe has revealed that startup firms suffer from liquidity constraint (Evans and Jovanovic 1989; Holtz-Eakin, Joulfian, and Rosen 1994; Lindh and Ohlsson 1996). Funding is also the largest problem for the startups in Japan. Survey of the Environment for Startups (SES) found that 49 percent of firms reported a “Procuring funds for entry.” “Procuring high-quality employees” and “Finding customers” were cited by 32 percent and 25 percent respectively. Problems of “Acquiring the specialized knowledge and skills for necessary skills” were cited by 20 percent, and problems of “Acquiring business knowledge (in finance, law)” and “Deciding site location” were cited by 18 percent and 17 percent respectively (Figure 1).

Given this circumstance, firm size at the time of startup is constrained by the amount of the entrepreneur’s holding assets. If government-affiliated financial institutions were willing to lend more money, entrepreneurs would prefer to begin with a larger-size firm. An empirical study using Japanese data confirms that entrepreneurs who used the National Life Finance Corporation as a source of funding were able to enlarge startup firm size even if other conditions were controlled (Yasuda 2005).

Based on this policy rationale, the government initiated a financial program especially for startups in December 2001. In this “New Startup Loan Program,” the National Life Finance Corporation lends up to ¥10 million for startups without requirement for collateral, guarantors, or personal guarantees. This scheme is widely used by startups, and between fiscal years 2002 and 2006 the number of cases from 2,975 to 7,942.

Other Policies Closely Linked to Startup

In addition, some policies that were taken in the first half of 2000s were closely linked to fostering the startup environment. One of these measures is expansion of the upper amount limit of “free property,” i.e., property exempt from seizure under the Bankruptcy Law. The Legislative Council revised the Bankruptcy Law to expand the limit of free property from ¥210,000 to ¥990,000. This makes restarting easier for entrepreneurs who failed the first time around and lowers the risk of startup.9

FIGURE 1 Challenges during preparation for startup/entry: A high proportion feels challenged by procuring funds for entry.

NOTE: Due to multiple responses, the total exceeds 100 percent.

SOURCE: Applied Research Institute, Inc., Survey of the Environment for Startups, November 2006.

3.

PRELIMINARY ANALYSIS OF THE BUSINESS AWARENESS OF STARTUP SUPPORTING POLICY

3.1

Business Awareness of Startup Supporting Policy

If Japanese policies to promote entrepreneurship are to succeed, government officials must identify and understand latent and potential entrepreneurs, design information campaigns that will ensure that these people are aware of the new policy incentives, and monitor how the policies influence the target audience.

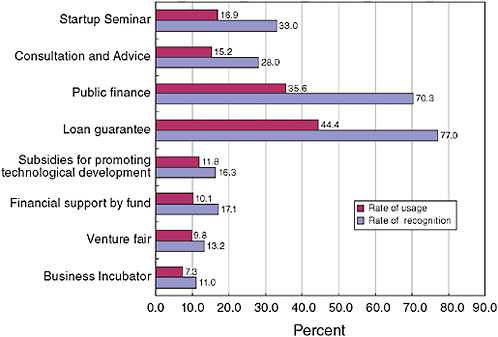

FIGURE 2 The rate of recognition and usage of startup-related policy by new startups.

SOURCE: Japan Small Business Research Institute, Survey of the Environment for Startups, Tokyo: Japan Small Business Research Institute, 2002.

We therefore investigated the degree of recognition in Japan of SME policies that are aimed at new business entrants.10 First, we show the results of responses to the questions of whether entrepreneurs at time of startup were aware of each startup-related policy carried out by national and regional governments and agencies (Figure 2). As shown here, although policies concerning startup finance are rather well known by entrepreneurs, other policies are less known to them. At the same time, a highly positive relationship can be observed between the degree of recognition and the degree of use of policy measures.

3.2

Model for Estimation

Next, we move to the question of which entrepreneurs acquire information on policies useful for startups and which do not. We used the Probit model of regression analysis to decipher which entrepreneurs and what types of firms were aware of various policies at time of startup. We asked about the following policies:

-

Startup seminar—"Startup Classes" and "Seminars for Promoting Startup" by Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Local Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

-

Consultation and advice—Inquiry counter for business counsel and advice for SMEs and business ventures.

-

Public finance—Loan by National Life Finance Corporation, Japan Finance Corporation for Small and Medium Enterprise and Shokochukin Bank (The Central Cooperative Bank for Commerce and Industry), etc.

-

Loan guarantee scheme by loan guarantee association established by each prefectures and the nation.

-

Subsidies for promoting technological development by the central government (“Japanese SBIR”).11

-

Financial support by venture fund organized by local government and Small Business Investment & Consultation Co.

-

Venture Fair—Exhibition for business venturing by Organization for Small & Medium Enterprises and Regional Innovation.

-

Business Incubator—Business workplace for business venturing; established by Organization for Small & Medium Enterprises and Regional Innovation, etc.

The attributes of entrepreneurs that we considered were:

-

Entrepreneur age at the time of startup.

-

Gender.

-

Education: a university gratitude or higher, or not.

-

Related work experience.

-

Business management experience.

-

Startup type dummies: spin-off,12 franchise, independent, family business and the others. (The benchmark is “the others.”)

-

Personal income level just before startup.

We also considered the following firm attributes:

-

Number of workers at the time of startup.

-

Legal form at the time of startup: limited liability or not.

-

Sector: manufacturing, transportation, communication, retail, wholesale, restaurant, service.

3.3

Dataset and Basic Statistics

In this section, we show the contents of the dataset used. Our dataset is from Survey of the Environment for Startups. This survey was conducted by the Japan Small Business Research Institute from October-December, 2002. The objects of survey were 10,000 firms that started business during 1995-1999 extracted randomly from the database of Tokyo Shoko Research, Ltd, (TSR). The survey was conducted by mail (response rate 11.4 percent), and the main questionnaire item was an archival record of entrepreneur, basic data of startup firm, usage of policy, etc. The number of observations with information on explanatory variable is 894.

Annexes A and B show the basic statistics of these variables. (Major features such as age distribution, sectoral composition, etc., could be discussed).

4.

ESTIMATION RESULTS (BASIC ATTRIBUTES OF ENTREPRENEUR AND RECOGNITION OF STARTUP PROMOTION POLICY)

The results of the estimations are depicted in Table 1. From these estimations, we could identify the following three findings on awareness of policies supporting startups by entrepreneurs.

-

Entrepreneurs with business management experience tend to have more information on startup-support policies at the time of startup.

-

Entrepreneurs with related work experience have more information on financial-support policies for startups.

-

Older entrepreneurs are often not aware of financial-support policies.

-

“Family business development-type” entrepreneurs tend to be less aware of financial support policies.

Based on these findings, the following interpretations can be made. The first finding can be explained by the notion that many entrepreneurs with business management experience are "serial" entrepreneurs already possessing startup experience. The second finding shows that entrepreneurs with related work experience have an advantage in acquiring information on financial support policy by way of their previous work; however, they do not know about expanded policies for promoting startups because many of them have no experience at the startup stage. Underlying the third and forth findings is the fact that older and "family business development-type" entrepreneurs are under less liquidity constraint. They do not need to make an effort to search useful policies for starting up.

5.

FURTHER CONSIDERATION OF THE OBSERVATIONS AND LESSONS FROM JAPAN

In the previous section, we noted that entrepreneurs with business management experience, many of whom are considered to be “serial” entrepreneurs, could

more easily acquire information on startup-support policies. One reason for this is that organizations responsible for providing this information are connected to the Small and Medium Enterprise Agency with which these serial entrepreneurs are likely to be familiar. These include:

-

Government-affiliated agencies such as Organization for Small & Medium Enterprises and Regional Innovation, JAPAN, Small Business Investment & Consultation Co. Ltd. etc.

-

Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Society of Commerce and Industry.

-

Government-affiliated financial institutions such as National Life Finance Corporation, The Central Cooperative Bank for Commerce and Industry and Japan Finance Corporation for Small and Medium Enterprises, etc.

Indeed, these organizations are well known among existing SMEs, but they could be completely unfamiliar to the first-time startup firm. Managers of these new companies might feel hesitant to visit the organizations that work with the locally renowned SMEs.

The crucial point is that "small business policy" and "entrepreneur support policy (startup supporting policy)" is different things (Lundstörm and Stevenson 2001). In the context of Japan, as mentioned in the first section, small business policy which is based on the Old Law is one thing, and startup supporting policy based on the New Law is another, and it could even be said that the two are conflicting. If the two policies have quite different target firms, the outreach strategy should also be different for each.

The consideration of startup policies up to now poses a new challenge as to how to reach new business entrants. Government must develop new communication channels. For example, the network of gas stations or post offices might make an effective new route. The public bank system might be useful. Moreover, and above all, it is necessary to reevaluate lessons passed to entrepreneurs from mentors, most of whom have startup experience.

6.

CONCLUSION

In this part of this volume, we have reviewed the history and current status of policies for supporting startups. Three main pillars of startup support policies and other measures concerning startup promotion were described. From these descriptions, we can also see that in the past 10 years the mindset of Japanese government has significantly changed from the view that a high level of business entrants brings about excessive competition among SMEs to the view that entrepreneurial activities are indispensable for vitalizing the national economy.

However, in order for new policies to work well, it is essential for new entrepreneurs to be aware of them. That is, effective outreach is the first essential step for a successful policy. Survey results that those firms that are already part of the

TABLE 1 Estimation Results

|

|

Startup Seminar |

Consultation and Advice |

Public Finance |

Loan Guarantee |

Subsidies for Promoting Technological Development |

Financial Support by Fund |

Venture Fair |

Business Incubator |

|

Entrepreneur Age at Startup |

0.008 (0.006) |

0.003 (0.006) |

−0.012** (0.005) |

−0.014*** (0.005) |

0.011 (0.007) |

−0.003 (0.006) |

−0.001 (0.007) |

0.005 (0.007) |

|

Female Dummy |

0.156 (0.274) |

−0.008 (0.289) |

0.023 (0.267) |

0.265 (0.274) |

−0.712 (0.537) |

−0.417 (0.391) |

−0.020 (0.351) |

−0.235 (0.415) |

|

High Education Dummy |

−0.047 (0.096) |

−0.012 (0.099) |

−0.010 (0.090) |

−0.066 (0.091) |

−0.114 (0.119) |

−0.156 (0.113) |

−0.112 (0.120) |

0.200 (0.133) |

|

Related Work Experience Dummy |

0.078 (0.121) |

0.104 (0.124) |

0.188* (0.111) |

0.208* (0.111) |

−0.022 (0.146) |

0.111 (0.143) |

−0.039 (0.144) |

−0.036 (0.154) |

|

Business Management Dummy |

0.135 (0.104) |

0.185* (0.106) |

0.507*** (0.099) |

0.451*** (0.100) |

0.249** (0.125) |

0.262** (0.119) |

0.178 (0.129) |

0.346*** (0.135) |

|

Spin-off Type |

−0.209 (0.192) |

−0.207 (0.200) |

−0.289 (0.185) |

−0.561*** (0.191) |

−0.157 (0.237) |

−0.593*** (0.219) |

−0.271 (0.229) |

−0.435* (0.240) |

|

Franchising Type |

0.088 (0.291) |

−0.222 (0.329) |

−0.161 (0.287) |

0.012 (0.295) |

−0.166 (0.426) |

−0.645 (0.425) |

−0.004 (0.352) |

−0.838 (0.530) |

|

Independence Type |

−0.224 (0.165) |

−0.080 (0.172) |

−0.039 (0.160) |

−0.188 (0.167) |

0.015 (0.203) |

−0.332* (0.181) |

−0.244 (0.195) |

−0.436** (0.199) |

|

Family Business Development Type |

−0.391 (0.248) |

−0.149 (0.253) |

−0.881*** (0.237) |

−0.419* (0.234) |

−0.528 (0.347) |

−0.453 (0.288) |

−0.503 (0.318) |

−0.460 (0.308) |

|

|

Personal Income Level Just Before Startup |

¥2.5 million or less |

0.030 (0.218) |

0.185 (0.221) |

0.125 (0.204) |

−0.096 (0.203) |

0.412 (0.256) |

0.334 (0.241) |

0.256 (0.262) |

0.588** (0.272) |

|

¥2.5-5 million |

0.017 (0.136) |

0.158 (0.139) |

0.072 (0.126) |

−0.128 (0.127) |

−0.175 (0.188) |

−0.266 (0.179) |

0.081 (0.178) |

0.330* (0.191) |

|

|

¥10-15 million |

−0.028 (0.125) |

0.041 (0.128) |

0.090 (0.116) |

0.035 (0.118) |

0.088 (0.148) |

0.115 (0.142) |

0.203 (0.156) |

0.335** (0.168) |

|

|

¥15 million or more |

−0.148 (0.179) |

−0.032 (0.182) |

−0.075 (0.166) |

−0.239 (0.166) |

0.065 (0.205) |

0.215 (0.194) |

0.359 (0.202) |

0.481** (0.217) |

|

|

Limited Liability |

0.152 (0.146) |

0.126 (0.151) |

0.050 (0.133) |

0.194 (0.133) |

0.098 (0.189) |

0.272 (0.187) |

−0.049 (0.176) |

0.157 (0.204) |

|

|

Natural Legalism of Employment at Startup |

−0.052 (0.057) |

0.035 (0.058) |

0.010 (0.052) |

0.182*** (0.053) |

−0.049 (0.070) |

0.036 (0.065) |

−0.023 (0.070) |

−0.164** (0.079) |

|

|

Constant |

−0.916*** (0.346) |

−1.082*** (0.354) |

0.162 (0.323) |

0.211 (0.330) |

−1.700 (0.429) |

−1.003** (0.404) |

−1.001** (0.421) |

−1.470*** (0.461) |

|

|

LR chi2 |

28.01 |

20.22 |

72.13*** |

70.13*** |

51.28*** |

46.65*** |

18.90 |

894 |

|

|

Number of Observation |

38.73** |

894 |

894 |

894 |

894 |

894 |

894 |

894 |

|

|

NOTE: ***=1 percent significant level, **=5 percent significant level, * =10 percent significant level; Figures in parentheses indicate standard error; Coefficients for industry dummies are omitted. |

|||||||||

SME network have little trouble learning about new policies to assist startups. But first-time entrepreneurs are not part of the SME network and are not receiving the necessary information. Government must develop separate communication channels to reach these new entrepreneurs, who in many ways dwell in a different world from the SMEs. For startup-promotion policies to achieve all their goals, they must be effective in reaching the latent and potential entrepreneurs.

REFERENCES

Applied Research Institute, Inc. 2006. Survey of the Environment for Startups. Applied Research Institute. November.

Evans, D., and Jovanovic, B. 1989. “An Estimated Model of Entrepreneurial Choice under Liquidity Constraints.” Journal of Political Economy 97:808-827.

Fan, W., and White, M. J. 2002. “Personal Bankruptcy and the Level of Entrepreneurial Activity.” NBER Working Paper, Series 9340. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Himmelberg, C., and Petersen, B. C. 1994. “R&D and Internal Finance: A Panel Study of Small Firms in High-Tech Industries.” Review of Economics and Statistics 76(1):38-51.

Holtz-Eakin, D. Joulfian, D., and Rosen, H. 1994. “Striking it Out: Entrepreneurial Survival and Liquidity Constraints.” Journal of Political Economy 102(1):53-75.

Japan Small Business Research Institute. 2002. Survey of the Environment for Startups. Tokyo, Japan: Japan Small Business Research Institute.

Lindh, T., and Ohlsson, H. 1996. “Self-Employment and Windfall Gains: Evidence from the Swedish Lottery.” Economic Journal 106:1515-1526.

Lundstörm, A., and Stevenson, L. 2001. Entrepreneurship Policy for the Future. Stockholm, Sweden: FSF.

Small and Medium Enterprise Agency in Japan. 2002. “White Paper on Small and Medium Enterprises in Japan.” Tokyo, Japan: Japan Small Business Research Institute.

Small and Medium Enterprise Agency in Japan. 2003. “White Paper on Small and Medium Enterprises in Japan.” Tokyo, Japan: Japan Small Business Research Institute.

Yasuda, T. 2005. “Seisakukinyuu no riyou” (The Utilization of Public Finance), in Nippon no shinki kaigyou kigyou (Startup Enterprises in Japan). K. Kustuna and T. Yasuda, ed. Hakutousha.

ANNEX A Basic Statistics for Entrepreneur Attributes

|

|

30 years old or less |

31-40 years old |

41-50 years old |

51-60 years old |

over 60 years old |

|

Age of entrepreneur at time of startup |

5.8% |

22.0% |

37.8% |

29.6% |

4.6% |

|

Female |

2.9% |

|

|

|

|

|

High education |

57.4% |

|

|

|

|

|

Related work experience |

79.6% |

|

|

|

|

|

Business work experience |

32.2% |

|

|

|

|

|

Startup type |

Spin-off type |

Franchise type |

Independence type |

Family business development type |

Others |

|

|

15.8% |

3.2% |

65.9% |

6.4% |

8.7% |

|

Personal income level just before startup |

¥2.5 million or less |

¥2.5-5 million |

¥5-10 million |

¥10-15 million |

¥15 million or more |

|

|

5.6% |

17.6% |

43.3% |

24.3% |

9.3% |

ANNEX B Basic Statistics for Firm Attributes

|

Number of workers at the of startup |

5 workers or less |

6-20 |

21-35 |

36-50 |

51-65 |

66-80 |

81-95 |

96-110 |

111 or more |

|

|

53.0% |

37.1% |

5.4% |

1.3% |

1.3% |

0.4% |

0.4% |

0.1% |

0.8% |

|

Sector of startup firm |

manufacturing |

transportation |

communication |

wholesale |

retail |

restaurant |

service |

|

|

|

|

20.0% |

2.2% |

1.3% |

27.3% |

15.4% |

1.5% |

32.2% |

|

|

|

Legal form at startup |

limited liability |

unlimited liability |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

85.9% |

14.1% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|