6

Creating a Next-Generation Data Utility: Building Blocks and the Action Agenda

INTRODUCTION

The collective experience of presenters, workshop participants, planning committee, and Roundtable members offers many important insights on how the future architecture and policies of data systems can aid in leveraging health data to its fullest and best uses. Perspectives summarized in this chapter reflect on lessons from successes and failures across the healthcare industry to provide guidance for the development of next-generation applications and progress acceleration in the public health data agenda. Underlying the discussion summarized here is the principle that new data utilities will build on considerable past progress. Offered in this chapter are summaries of workshop presentations and a panel discussion that provide a mix of theoretical perspectives and specific ideas for practice to guide future work.

Building blocks for a next-generation public agenda were described by three presentations based on lessons learned about strategic priorities from past and ongoing work. Christopher Forrest, professor of pediatrics, senior vice president, and chief transformation officer at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), presents a CHOP initiative to transform the delivery of pediatric care and children’s health through the power of data-driven decision making. Forrest describes CHOP’s highly linked data system, which includes genomic, clinical, and environmental data used to support the organizational vision of transforming pediatric care, and discusses issues related to collaboration: developing cross-institutional relationships, providing the patient and family access to information, fostering provider–payer relation-

ships, working to reduce costs (both financial and nonfinancial), changing cultural assumptions, and improving communications. Brian Kelly, executive director of the Health & Sciences Division at Accenture, a global management consulting firm, details some challenges of managing and aggregating multiorganizational data and the associated influence of current privacy regulations on data activities, including practical challenges and the many entrenched and difficult-to-change systems for data aggregation. Guidance is needed on approaches to ensuring individual health data protection, questions of data ownership, on conveying the benefits of providing access to healthcare data through public advocacy initiatives. Finally, Eugene Steuerle, senior fellow at the Urban Institute, reviews current incentives to share health information that are at odds with positioning clinical data as a public good. Although the benefits of clinical data can be shared by all, the distribution of costs associated with collecting, storing, and analyzing the information are borne by few. In addition, the significant issues with privacy and confidentiality, bureaucratic policies, and providers and intermediaries further complicate structuring incentives, whether financial or otherwise, to share clinical data. Steuerle offers several suggestions on means of restructuring incentives associated with collecting and aggregating clinical data for healthcare improvement and suggests that consumers of health services may ultimately need to be the driving force behind changing current incentives to foster a more favorable approach to clinical data.

The chapter concludes with a summary discussion of six panelists, charged with moving the conversation around a next-generation data utility to an action agenda. The six panelists are Stephen Phurrough, director of the Coverage and Analysis Group at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS); James Ostell, chief of the Engineering Branch of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI); John Lewin, chief executive officer of the American College of Cardiology (ACC); Evelyn Slater, senior vice president of Worldwide Policy at Pfizer; Janet Woodcock, deputy commissioner and chief medical officer of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA); Arthur Levin, cofounder of the Center for Medical Consumers; and session chair David Blumenthal, director of the Institute for Health Policy at Massachusetts General Hospital/Partners Health System. They discussed critical questions, including what decisions and actions are needed to advance access to and use of clinical data as a means of advancing learning and improving the value delivered in health care, and they offered perspectives on current activities and opportunity areas in the development of healthcare data resources. Current and emerging “what if?” opportunities to align policy through multiple stakeholder engagement are considered, along with implications of recent legislative initiatives. The identification of opportunities for enhanced coordination, investigation into aspects of policies on consent for data sharing and

research, and active translation of data insights to better engage the public emerged as important areas for future work.

BUILDING ON COLLABORATIVE MODELS

Christopher Forrest, M.D., Ph.D.

Senior Vice President, Chief Transformation Officer

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

The Institute to Transform and Advance Children’s Healthcare (iTACH) at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia is spearheading a novel effort to harness clinical, business, research, and public health information to improve children’s health, make their health care more efficient, and transform the delivery system. The Institute has developed a data system that links the full spectrum of information about a child’s health needs, from genomics to clinical to environmental data, in order to build out a vision of personalized pediatrics. This paper will provide an overview of this new approach to healthcare delivery and will assess issues related to collaborative relationships that are needed to realize a vision of personalized pediatrics, including forming linkages with multiple pediatric institutions, giving patients and families access to their data and obtaining information from them, and creating provider–payer collaborations.

In our organization I sit at the nexus of biomedical and applied informatics, genomics and other types of molecular diagnostics, healthcare management, quality and patient safety, and translational medicine—translating scientific discovery into clinical care using health information technology. One of the most urgent goals at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia is to transform ourselves into a data-driven healthcare organization. We view data as an essential asset that is just as important as the people in the organization, our financial reserves, and the buildings that we are building.

CHOP is the largest integrated pediatric network in the country, if not the world. We have 35 primary care practices and several specialty clinics located in 3 states, and have nearly 2 million encounters a year. We have an integrated specialty network, and staff both a 500-bed central hospital and a number of other community hospitals. We use electronic health records (EHRs), but we believe the EHR is just one piece of the health information technology needed for personalized pediatrics.

In the process of trying to become a data-driven organization, we have created a novel concept of personalized pediatrics, which we see as much broader than that of personalized medicine, which too often becomes conflated with pharmacogenomics. To build our concept of personalized pediatrics, we will need to create a number of collaborations that we are

either developing or need to develop—collaborations with other pediatric institutions, public institutions such as local government, payers, and patients and families.

Our concept of personalized pediatrics is one of CHOP’s primary strategic initiatives. We think this is the future of health care—in fact, a new form of health care—and we are devoting substantial new investments to it. We believe all health care will become more data driven, much like other service industries. In so doing, we seek to go beyond conventional quality improvement, which tends to focus on process change and reliability of service provision. Personalized pediatrics is an approach to health care that customizes delivery of services to the individualized needs of children and adolescents. Conventional modes of treatment are based on caring for the “marginal patient” because so much of our medical evidence is based on average treatment response. Our model is predicated on giving care at the right time by the right person, in the right setting, minimizing waste, and shifting services from specialty to physician-focused and nurse-focused primary care, even at the home whenever possible. We believe that to be successful, we have to generate value for people, which translates into less time spent in health care, paying less out of pocket, and the ultimate goal, getting better more quickly.

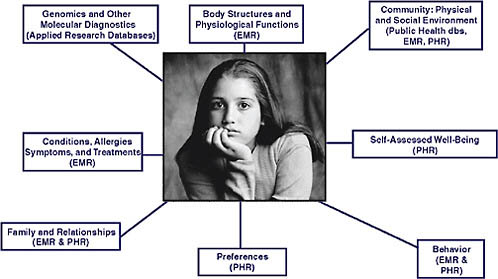

To implement personalized pediatrics, we need to construct a biopsycho-environmental profile for every patient (Figure 6-1). Data for this profile are

FIGURE 6-1 The biopsychoenvironmental profile and required data sources.

NOTE: dbs = database, EMR = electronic medical records, PHR = personal health records.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

obtained from electronic medical records (EMRs), applied research databases, public health sources, and directly from patients and families using personal health records (PHRs). For now, genomics, gene expression, and other types of molecular diagnostics are collected as part of human subjects research. Within the next few years, however, we expect these types of data to be part of the portfolio of advanced diagnostic laboratory medicine and thus be available in the EHR. CHOP is building a patient portal into the electronic health record. It is not a full PHR, but at least it gives patients the ability to access their own data and input a limited set of information. The full biopsychoenvironmental profile, when fully available and used to improve care, will be a major advance in our ability to better personalize care, predict future health events, and ultimately prevent ill health.

Well-child care (i.e., preventive care services for children that are focused on optimizing health and development) has been the bedrock of pediatrics for years. Recommendations for the specific set of services are made according to age and sex, even though the risk for poor health and functional outcomes varies dramatically within age–sex groups. Where we are headed is toward more personalization of delivery of well-child care, according to factors such as the social complexity of the family and the risk of the child for early school failure. This type of information needs to be collected directly from parents in a uniform, structured way and incorporated into a biopsychoenvironmental profile to enable specific customization of preventive care. These measures of developmental and social risk will be used to produce scores that can be used to partition patients into “tiers” of need for preventive services based on their likelihood of poor future outcome.

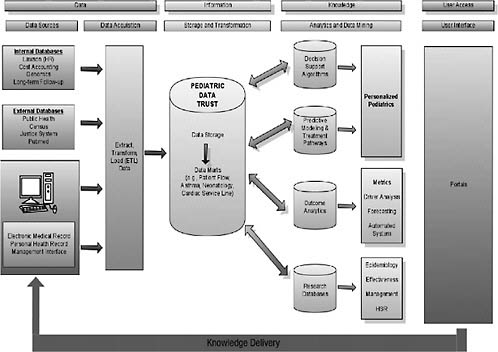

The technology driver underpinning personalized pediatrics and improvement of outcomes for children is what we call the Pediatric Data Trust (PDT) (Figure 6-2). We use the word “trust” to convey two deliberate messages. One is the notion of a bank—your data are stored in a vault, they are going to stay there, they are not going to go to anybody else who may misuse the data, and the kinds of transfer we are engaged in are not to payers. The second connotation of trust is that patients can trust us with their information. Various types of data systems feed into this large data warehouse; electronic medical records are just one piece. In fact, to make personalized pediatrics work, data from the electronic medical record is insufficient; it needs to be greatly augmented with other data sources. We use a large vendor (Epic) to collect our EMR data, but to transform care we have to integrate multiple types of data and store them in a sophisticated relational database—the pediatric data trust. In addition, there is an applications layer integrated into the PDT that runs analytics and other kinds of algorithms to identify clinical decision support opportunities. The real technical challenge with which we struggle is this question: Once you have

identified a need and you want to personalize care, how do you take that information and transmit it in a timely way to the right decision maker, whether he or she is a patient, family member, clinician, or manager? It is one thing to build clinical decision support right into the electronic health record, but more advanced support—say, by linking genomics with patient preferences and clinical data—requires a kind of knowledge delivery system and creates technical hurdles that prove to be incredibly challenging.

CHOP recently established the Center for Applied Genomics, the largest genotyping facility of its type in the world devoted exclusively to understanding the genetics of pediatric disorders. The Center has conducted whole-genome analyses on more than 50,000 individuals, and in some cases their parents. When kids have a blood draw at a CHOP facility, our process calls for a research assistant to ask their parents whether they would like to have their child genotyped. The system is fully automated, using robots in the genetics lab to perform the assay on a platform capable of reading 500,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (soon to be a million SNPs) for about $750 per test, a cost that is rapidly decreasing. Our goal is to identify new gene–disease associations, use that information to subclassify patients with a particular disorder, learn what treatments work best for each subclass, and then drive that information back into the clinical record. For example, let us assume that we have identified four genetic subclasses for patients with asthma. The Pediatric Data Trust is used to rapidly learn how alternative treatment pathways relate to those genetic subtypes and outcomes of care. We may learn that one type of inhaled corticosteroid is most effective for Subclass 1, while another is most effective for Subclass 2, and so on. Then if a patient with asthma has genetic Subclass 1, one set of order entry templates would be used, facilitating the usage of the “right” corticosteroid according to the genetic profile. In other words, we believe that the day when genomics and other molecular diagnostics information is embedded into the workflow of the physician—one of our ultimate goals with personalized pediatrics—will arrive in the near future.

A variety of types of collaborations will be important to the success of personalized pediatrics. Because so many conditions are uncommon in children, we will need to link databases across multiple pediatric healthcare organizations. Leadership for this type of clinical data linkage could be provided by the National Associations of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions or the Child Health Corporation of America; both are professional organizations for children’s hospitals and both currently collect administrative data from hospital discharge abstracts. Unfortunately, neither has yet embraced the collection of clinical data. Consequently, iTACH has been working with these partners and others to build the case for a national, even global, clinical database that would link the pediatric data trusts of multiple institutions. In the model we are developing, an

organization retains its own local pediatric data trust—not just the EMR, but also other kinds of biological and environmental data linked in a deidentified way. The data would be sent to a central repository, a national PDT. Standards will be critical here, some of which need to be developed (e.g., genomics). We believe an integrated PDT is going to be of incredible importance not only for benchmarking outcomes data, but also for mining information to identify the most effective treatments for patients with uncommon conditions, which is much of specialty pediatric practice. Our partner pediatric institutions are excited about this, and we are exploring ways to make this vision a reality. We know we are going to need better clinical data systems; administrative data from hospital discharge abstracts are not helpful for improving care for children. Large pediatric institutions will probably need to develop these systems themselves. We are not seeing leadership from the federal government, state governments, or any professional societies, at least in pediatrics.

Local government is the other partner that we need to make personalized pediatrics work. More than 250,000 kids are in CHOP’s primary care network. With the data we have, we are able to geocode patients according to their place of residence. We can use this geographic information to identify and track epidemics, the leading edge of influenza, respiratory viruses, and infections. We also think we should start linking in pedestrian injury information, which, for example, we might obtain from police records. With such information in the EHR, a physician would know whether a child lived in a neighborhood where there is a high rate of pedestrian injuries and could customize preventive services and counseling around prevention of accidents for high-risk families.

We need information from the public sector, and we want to give information back to the public sector. There is a great deal of interest in Philadelphia on ways to address the childhood obesity epidemic. In our data trust, we have information that we would like to make available in some way to the local government. We can, for example, sort children in our database according to their body mass index and place of residence. We anticipate being able to look at these data over time and build predictive analytics as to which kids are more likely to be overweight. Right now the information is simply used for case finding; it needs to be linked with public health programs. Forming that linkage and getting the cooperation of local government to work with us has been very challenging, but it is definitely a direction of the future.

We also need to work with payers. We know about the care that children receive in our own network, but we have very limited information about the care they receive out of the network. Our local Blue Cross Blue Shield plan is interested in participating with us in a community-wide childhood chronic disease management program, say for asthma. With this type

of payer–provider collaboration, our organization will be able to receive from the payer healthcare, medication, and laboratory data on children who receive services outside of our network. All that information gives us a more complete picture to provide better quality care for asthma, improving children’s health and keeping them out of the hospital. We are also exploring ways to work with other payer partners to develop a child-specific personal health record. If we really want to use data to improve kids’ care, we believe there will be a need for a longitudinal personal health record, which will be the central repository of information for children. None of these programs will work without the support and participation of families. Our model of care is highly family centered. Everything we do is designed in partnership with families. We believe our privacy statement is quite good on Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and Institutional Review Board issues. It does not, however, address issues about data mining, that gray zone between research and clinical care.

Our researchers strongly believe that any patient who walks through our doors is a research subject, that their data are the property of the institution and should be available to investigators for research. I am unsure whether our patients would agree with this position; we have never made this philosophy public nor have we had a public discussion on use of data for outcomes improvement and research. We also have not engaged in a discussion of personalized pediatrics with families. Although the notion of linking genomics all the way to the environment sounds good to us as providers, we do not have a sense about how this concept will be received by the public. That is a discussion we are going to need to have with our community. We will need to sort out whether we are going to require everybody who comes through our doors to approve the use of their data for quality improvement purposes, or whether we are going to make this optional.

In conclusion, personalized pediatrics is not only a critically important future for health care, it is where we are going to find real value for children and their families. We do not think better health achieved at lower costs is possible with process and quality improvement alone. Customizing care to the individual needs of a patient, tailored to a unique biopsychoenvironmental profile, will be necessary to truly transform child health. Personalized pediatrics focuses on outcomes, changes in health, and reductions in costs, both financial and nonfinancial. Three big challenges will be culture, communication, and collaborations. Changing the culture of our providers to collect data in a high-quality way is dramatically difficult. You can put a provider on the electronic health record, but getting the provider to enter accurate and valid data may take many more years. Communication about our intentions and having a dialogue about how to partner personalized pediatrics, particularly with families, is critical; it is something we must do

right now. To make this work, we have to make successful all the collaborations mentioned above.

TECHNICAL AND OPERATIONAL CHALLENGES

Brian Kelly, M.D.

Executive Director, Health and Life Sciences Division, Accenture

This paper provides an overview of many of the technical, operational, and organizational challenges faced when attempting to aggregate clinical data from multiple institutions to gain insights on clinical effectiveness or drug/device safety. Drawing on experiences from previous pilot projects and other work in this area, the paper will (1) provide an on-the-ground, real-life implementation perspective on the challenges of aggregating data from multiple sources for secondary use, and (2) discuss the impact of current privacy regulations. Issues of how current privacy rules inhibit the merging of data on individual patients for non-HIPAA-sanctioned public health use cases will be discussed.

Data sharing across institutions presents considerable technical and operational challenges. Part of this perspective comes from work done building a prototype for the Nationwide Health Information Network (NHIN), in which researchers tried to aggregate data from 15 different organizations in 4 states. The development of what Accenture had to do—from a technical architecture perspective and a business process perspective—to get people to agree to share that data is discussed. In addition, in just the past few months, we have worked with several organizations that are coming together to determine how we can begin to take data that have already been aggregated by some of the large data aggregators and to merge those data into very large datasets for purposes of monitoring drug safety adverse event signal detection. When you take data that have been aggregated and then try to aggregate them again, you have a volume of data sufficient to actually derive statistically significant findings, but such an avenue has its own set of challenges. The technical challenges and policy needs for this scale of data sharing are also explored. Topics discussed include critical features necessary to aggregate data for secondary use, challenges, opportunities, the limits on data sharing outside single care delivery systems, limits on the secondary use of non-HIPAA sanctioned data, and the need for education and advocacy for using data as a public utility.

Around the globe, payers, pharmabio companies, governments, and hospitals are working to improve health care. Data sharing is absolutely critical to all of these. The healthcare ecosystem is a $3 trillion business, but no one really shares data—for many reasons. One is that in many instances,

not sharing data gives them a competitive advantage. Sometimes, it is just too hard to share data because the standards to share that data are too different. Organizations around the world say they could be more effective if they had other organizations’ data and could leverage that. Getting to that point is a wonderful vision, but major obstacles must be overcome.

Accenture’s approach to facility data sharing for our NHIN prototype will illustrate what you really have to do to share and standardize data so that you can actually run secondary analysis on it and derive insight, which then can translate into improvements in care and outcomes. We had 15 separate hospitals. Each had its own registration system, lab system, and medication or pharmacy system, and in most instances those systems were not the same. Each hospital had completely unique platforms, with no common standards. Really, it is a data mess out there at the hospital level. Each of the 15 hospitals were aggregated into groups of 5, basically 1 group per state, and aggregated a subset of their data into a core data repository. The data aggregated were data critical to patient care, including demographic data, recent lab data, medications, allergies, and past medical conditions. Although we could have also pulled in other data, we elected to concentrate on these datasets because they were seen as core components to delivering clinical care.

We aggregated the data with an EMR view and a PHR view. Then we merged those data from those three regional areas into a central repository where we could perform secondary use. We made sure that the data were sent through messages that were standard HL7 version 3 messages. We spent probably most of our time mapping data elements to CPT4 codes, ICD9 codes, and to Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT) codes. We did a lot of heavy lifting on a small number of patients, showing that it is theoretically possible to do this.

This work is necessary to facilitate data sharing to produce aggregated data that would enable secondary use. The extensive data mapping we did is not necessary if one is focused on a single patient and does not intend to use the data as a tool to improve care. A doctor seeing a single patient, with lab results, medication charts, and so forth, can figure out how to take care of that patient. Although the physician cannot use EMR capabilities that reside in an EMR, such as decision support. if the data are not normalized, he or she could probably still do a fairly good job of taking care of that patient. To optimize care and secondary use, however, it is necessary to do the heavy lifting of putting the data into equivalent standards and terms.

It is important to recognize that systems that currently exist in hospitals are going to be there for many years. The average lifecycle of a typical hospital system is more than 20 years. People think these things are new systems and that they frequently change all over, but that is not the case. People make major capital investments in these systems over time, and so

their replacement is going to be incremental. It will be a generation before many hospital systems have turned over completely. For example, some of the best systems are in the Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Their development started in the late 1980s and while they are clearly migrating forward, they are leveraging their legacy systems and have not changed that fast. To connect to these core systems and exchange data among institutions requires a very sophisticated approach to information governance because people do care about who can see their data and under what circumstances.

When you start doing these types of projects, one of the first discussions concerns who owns the data, and whether they will share those data. Even if we say the patient may own the data, in reality whoever puts the data into a database owns the data. In this case, hospitals own the data we are discussing, and if they do not believe there is a compelling reason for them to share their data, they will not do so. If their main EMR system has data on 100,000 patients, and some data requests pertain to only 50 of their patients, they are highly unlikely to share data on the 99,500 other patients in their database. You have to anticipate this in advance and map a strategy to pull only the 50 patients willing to participate in this data sharing. Thinking about this from a technology perspective, that is a much higher bar than to just take a flat file download of data tables and import it. This is the reality, however, of the technical components necessary for true data sharing to occur for the public good.

If data are not standardized, they cannot be used for secondary use in any meaningful way. That means you are not going to be able to do good public health surveillance, you are not going to be able to provide good care management and you are not going to be able to do clinical research. Whatever architecture you come up with had better be able to store the data, either where they sit or centrally, and should reflect ground rules set in advance about the manner in which people agreed to share data.

To obtain a perspective of what we need to think about, let us consider a model of three hospitals that wish to share data. The first challenge is that if you are going to pull data from each hospital system, it would be preferable to have a single, super-standardized interface, but it is not that way. Each hospital is likely to have a different lab system, a different radiology system, and a different demographic system, and you are going to have to pull all of them. Assume, too, that there is a central node where you are going to aggregate data, and then allow your patients to access PHR data, allow physicians to aggregate EMR data from that, or allow a researcher to look at data analytic tools for secondary use.

You will first need to develop some sort of filtering mechanism that pulls only data on people who have agreed to participate in this data sharing. First, therefore, you need to have a way of identifying a specific

person—you have to know, for example, that I am Brian Kelly and this is where I live, and that I am the same Brian Kelly who has data in hospitals A and B, but not the same Brian Kelly who has data in hospital C. You cannot pull that data across a hospital’s firewall until you make that kind of identification—a hospital will not do random pulls of individual data based on the fact that a patient at the time of care signed a notification of privacy practices that said he will allow you to use his data for treatment, payment, and operations. That is the standard form. A key question, therefore, is what exactly is included in treatment, payment, and operations. That gets into a philosophical argument that most hospitals would rather not enter. Remember that health care is regulated at the state level, so while there is HIPAA, states can be much more restrictive than HIPAA, and in some instances they are. In our model for data sharing, therefore, the only way we could get this done—and we were doing this across four states—was to go out to patients and ask them whether they would allow us to use their data and participate in this prototype. When this becomes an outcomes and operational system and is being used for the care of patients, that restriction could potentially go away if a patient was going to rely on this tool as part of care, but for now you are still going to have to filter the patient data. For now, because patients are not getting care through this mechanism, you do not have a right to pull their data across, so you have to know whether the patient has opted to participate. We had to have each patient sign a consent form, which was essentially a notification of privacy practices allowing us to use their data for the purposes of this prototype. We then registered the patients centrally.

We then developed software tools that essentially had a small application that ran inside the hospital’s firewall. Every day, when they went to send messages out, they would basically bounce the name of the patient up against this application, which would have a list of all of the patients who agreed to participate and would only filter through and then centrally store data for people with a signed consent. This is the kind of reality that will impede data sharing. Unless, for example, we change the standard notification of privacy practices to say the data can be used if they are deidentified for secondary use in clinical research, we will continue to have a lot of trouble aggregating data among various institutions.

Patient approvals are just one issue. Another problem is that each system usually has its own unique standards for data (or may have no standards). If a system could spit out an HL7 message, we could take that HL7 message, but if you know anything about messaging you know that if you have seen one HL7 message, you have seen one HL7 message. They are all different and you have to standardize them to a common type. We not only had to map the messages, but we had to map every term for data that we pulled over. We did that all in our customized application. Making this even

more complicated is the design of the security architecture—determining who can see what data, and making provisions, for example, for a patient who says that one doctor can see my data, but another cannot. There must also be robust auditing capabilities. We found it helpful to make an audit log available to patients to show them who had accessed their data.

Sharing data presents many challenges, and what we did in the pilot test is not scalable without policy change. We could not go to an area that has 300,000 patients and do one-by-one enrollment applications. The only way we as a nation are ever going to get to data sharing is for there to be a national policy discussion and for us to agree how it would be possible to modify things such as notification for privacy purposes to facilitate data sharing, and spell out the restrictions. To share data among different delivery organizations, there could be a different approach to notification for privacy purposes. That is one of the biggest policy areas that we as a nation have to grapple with and discuss.

However, in our model we saw that once we did the heavy lifting to get the data into the data warehouse, then beauty can really occur. If you have a set of completely normalized and standardized data on your population, you can do some really interesting analytics. That is how we can actually make things happen and, ultimately, transform health care.

Apart from the project described above, I have been involved in a project focused on aggregated datasets. The idea is that you could go to large organizations that have already done a good job of aggregating data and collect the 10 biggest datasets that exist in the world, put them into a database, and merge them successfully. Such datasets would be that much more powerful for drug signal detection, drug safety monitoring, and studying all kinds of related questions. The problem we encountered is similar to pooling data across different hospital databases. Data aggregators pooled their data with organizations with which they had business associate agreements about how the data were going to be used. The agreements did not allow for the data to be used for secondary use unless they were deidentified. So some issues are involved. The only way to aggregate datasets is when the data are totally deidentified, but then when you merge the data, you would not know how many times a particular patient was represented in the mix. So a key question is how we can develop a master patient index function that allows you to index so that you know that these patients are the same. This is a big issue. Quite honestly there is some benefit for the public good to aggregating these large data sources, if a way could be found to solve the deidentification questions. Possible solutions include initially registering patients with a unique identifier that could then be associated for research purposes. Currently, however, from an operational perspective, it is extremely difficult to get past that challenge.

Finally, there is a need for advocacy for using data as a public utility.

Particularly in the hospitals and research institutions I have been able to visit over the past few years, I have seen some that have been very innovative about proactively reaching out to their patients to educate them about how important clinical research is to patient care. Many of these organizations have actively gone out and started essentially marketing campaigns to educate patients and their families on how important it is to participate in clinical trials and related research endeavors. We need to do the same thing to begin to educate people on how important it is to be able to use data for secondary purposes. Such efforts would need to address all the security and privacy issues because these factors are currently the biggest barriers to using data to improve public health.

ECONOMIC INCENTIVES AND LEGAL ISSUES

Eugene Steuerle, M.A., M.S., Ph.D.

Senior Fellow, Urban Institute

If we wish to change behavior, then we must directly address incentives. The existing incentive structure in health care discourages information sharing, giving great weight to possible errors in protecting privacy relative to errors in failing to use existing information to improve public and individual health. In addition, incentives internal to the bureaucracy also discourage optimal use of information, even such items as merging already existing datasets. Because government now controls nearly three fifths of the health budget (if we count tax subsidies), it has a primary responsibility to improve these incentives. Some incentive changes are possible now, through reimbursement and payment systems. Others require examining the reward structure internal to the bureaucracy. In the end, however, the primary incentive needs to come from consumer demand—operating either directly on providers and insurers, or on the voters’ elected representatives.

One does not have to be a genius to understand that incentives affect the extent of data sharing in health care. What are the incentives and barriers to providing this type of public good? In many cases the benefits from sharing clinical data and better use of clinical data are shared by everyone. Yet few individuals, insurers, doctors, or government workers gain by incurring more costs themselves. Accordingly, for solutions to data sharing, we have to examine and change the incentive structure.

The first incentive problem is that of the expected public good versus the potential private cost. One of the major barriers to moving forward here derives from the tension between privacy and confidentiality concerns and the goal of improving well-being through information sharing. From the privacy side, some people fear their data might be lost. Indeed, instances

of failure do occur—even on a grand scale, as when the Department of Veterans Affairs lost huge data files. So it is a real concern. Even if lost data were no problem, for their part, some individuals do not want to have their data shared, no matter what good sharing might do for the public. So there is this related fear of violating privacy as an individual right.

As one consequence, fairly significant threats of lawsuits often prevent some providers and vendors from taking actions that might serve the public good. But there is a large cost—the failure to improve the public good when in fact we know, we strongly know—that we can do it. We lack data sharing for individual care, we lack data sharing for an early warning system (e.g., through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] or other organizations), and we lack data sharing that would assist in finding cures or better treatments for various health problems and diseases. Researchers would probably agree that the costs are high, although I am not sure the public is totally convinced. In the end, we have to engage the public in these issues. That is the first incentive problem.

The second incentive problem is the lack of bureaucratic incentives to share datasets or for agencies to allow datasets under their purview to be shared. Imagine what we could do, for instance, if we could just merge some of our Medicare data, which are pretty significant, with other federal data. We have only barely begun to merge Medicare data with Social Security data, even though at one time those functions were housed in the same agency. Notwithstanding goodwill among many public servants who want to serve the public, there are strong disincentives in the bureaucracy to share and use data. One such disincentive is the possibility of bad publicity if something went wrong or if the information revealed failed policy. For many agencies avoiding bad publicity is a mark of success. You may never have a lot of friends if you are the agency privacy lawyer, for instance, and the bureaucratic instinct is to minimize your enemies.

To make matters worse, our democratic systems almost always work to put more demands on our public servants than they can possibly meet. If you are sitting in the bureaucracy, you cannot even get done what needs to be done—it is often difficult to accommodate someone who adds another task, such as merging datasets, even if it might provide some public good. Also, as anyone who worked in the government knows, there are calls every year to reduce spending. Research and statistics have been relatively easy budget functions to cut; from the politicians’ viewpoint, costs are diffuse and in the distant future—long after the next election. The key question, therefore, is how we can add incentives into the bureaucracy to reward people for undertaking publicly beneficial actions such as enhancing data sharing and helping to ensure that researchers somehow have access to those data.

A third incentive problem revolves around providers and intermediaries. An insurance company really does not have an incentive to do

anything more than to serve as an intermediary. It has little incentive to provide for the public good. Although companies do have some incentives to reduce relative costs, many of the public good issues we are talking about do not provide any gain for an insurance company itself. For the insurance industry as a whole, moreover, there is a perverse disincentive at play; for example, if cancer is cured through use of shared administrative or clinical data, insurance payments for the industry as a whole might be reduced.

Incentives for doctors are mixed, too. Knowing that a certain percentage of any population will inherently be below average, for example, why would a physician want to encourage relative comparisons of his or her success versus those of others if that is one result of data sharing? Some doctors also voice the fear that data sharing via EHRs will even give more information to insurers, making it easier for them to decide not to pay for elements of care.

From the doctors’ or hospitals’ perspective, development of better data may enhance the power of lawyers to sue. Data from some studies suggest that autopsies find that a large percentage of patients who die have been misdiagnosed at least to some extent—although often not enough to cause the death. Nonetheless, you can see the potential for lawsuits if these data were openly available.

For solutions to some of these issues, we have to find ways to change the incentive structure. Several possibilities are listed here, with the hope that readers would add to this list.

Government has a lot of leverage, not just because it cares about the public good. Government spends a lot of money on health care—nearly $11,000 per household. Factoring in tax subsidies with the direct subsidies, it provides nearly 60 percent of the financing of health care. The point is that government is the primary payer and player.

Medicare could pay more for e-prescribed drugs, less for those not e-prescribed (expenditure neutral). It could pay differentially for lab tests put into electronic form for sharing with patients or the CDC. It could pay for electronic filing of information on diagnoses and treatment.

Consider a condition such as autism, where we really seem to be at a loss in terms of the information we need. Few families are unaffected by autism somewhere among their relatives, and it is safe to guess that friends or relatives of children and adults with autism would consider the privacy risks modest relative to potential gains from developing a better data system aimed at discovering solutions. Through Medicaid, and programs such as those that provide education for the disadvantaged, federal and state governments are primary players here.

Certainly government could provide more incentives for participation

in clinical trials; one of the Roundtable themes is to engage and inform the public in evidence development strategies.

What should we expect from government efforts to change the incentive structure behind its payments? Often it does not really want to set the ultimate standard. Consider EHRs. A key set of questions again revolves around how government can appropriately set incentives for the development and use of such records. Because we have not solved the privacy issue completely, and likely never will, any system would probably have to give people some ability to bow out. But that cost might very well be worth the gains from more electronic filing of information on diagnosis and treatment, for instance. No one change in incentives can be expected to be perfect or get us completely where we want to be, but we can ratchet up the benefits from this type of information development and sharing.

People working in the bureaucracy currently get little reward for fostering data sharing. However, we do know that bureaucracies respond to incentives. Outside the healthcare field, for instance, we saw that welfare reform took hold when governors changed incentives for their head welfare officers. These officers were told that their success was going to be measured not by how much money they brought into the state from a federal government match, but by the number of people they got off welfare. Whether or not that was the right thing to do, it dramatically changed the entire welfare debate. Thus, even before formal legislated welfare reform, governors dramatically changed the entire operation of the welfare bureaucracy. Another example was provided by the United Kingdom’s recent efforts to reduce child poverty. The Prime Minister and Chancellor of the Exchequer (or head of the Finance Ministry) set as a target a zero poverty rate for children. Although that is probably not an attainable target, once they made the goal public, the whole government started changing the way it did things to try to come closer to the target.

Thus, the dynamics of a bureaucracy can be changed. Suppose as only a minor example that the head of a U.S. department decided to measure the number of research projects developed with each dataset. (That may sound like a trivial and fairly impure measure of success, but it is better than none.) As another example, he or she could ask for common standards and protocols to be developed for data sharing. As it now stands, often every time one wants to share data using some new dataset, the process requires running the gauntlet of a whole bureaucratic layer of decision making—including the confidentiality officer, typically a lawyer, who has every incentive to say “no.” Changing incentives within the bureaucracy often has to come from the top.

Finally, it is not clear that we will ever get enough information development and data sharing by looking only to doctors, insurers, and hospitals to somehow “do the right thing.” The good sought is for individuals, not

for those serving them. Ultimately, then, consumer demand probably has to drive the system. One need not be passive about it; such demand can be fostered. Imagine, for example, a Department of Health and Human Services Secretary who would go around the country and make the public case for e-prescriptions and for electronic reporting of lab tests, showing how such efforts could make individual health care more effective. The goal would be to encourage individuals, in turn, to demand improvements from their providers as a means of ultimately achieving better health care. Of course, the initial effort may not instantaneously result in datasets ideal for clinical research, but it would be a major step toward developing better data for those purposes, as well as better care for the individual.

There are other ways to foster demand, of course—in the example of families with an interest in autism, they would likely be quite willing to share data on the family.

In sum, there is no one-size-fits-all answer to the development of better shared clinical data. Incentives, however, can consistently be improved over time. I encourage all interested parties to add to the examples I presented here and to think rigorously about how to improve the incentive structure surrounding the development and use of data to achieve better health outcomes.

THE ACTION AGENDA

Engaging the spectrum of stakeholders working in healthcare data initiatives will be critical to the development of improved data generation, access, and evidence development. Opportunities to align policy developments or draw on synergies within organizations, initiatives, and advancements will serve to push the frontier of data collection and be used to drive the development of next-generation healthcare research and delivery. Workshop discussions included perspectives on the current and developing uses of healthcare data for insight, and presenters addressed opportunities to evaluate policies impacting the public good, security, and privacy aspects of data. Manuscripts in this chapter, as in previous ones, profile advancements and perspectives that might encourage the frame shifting associated with developing clinical data as a public good.

Summarized here are the discussions of a workshop panel featuring perspectives from government providers, researchers, and regulators; healthcare professional organizations; pharmaceutical manufacturers; patients; and consumers. Panelist comments focus on how the ideas and opportunities presented at the workshop might form the basis for an action agenda that will realize the full potential of developing initiatives and implications of new legislation on data initiatives. Approaches discussed aim to align

policy development with improved data access and evidence development, and to engage all stakeholders addressed.

Opportunities for Enhanced Coordination

Several workshop participants, both speakers and attendees, identified the need for a more coordinated approach to managing current data sources, ongoing research, and possible future synergies between the two and across the spectrum of stakeholders. Addressing the growing inefficiencies might yield greater health insights at less expense. There are needs for better coordination, a more standardized approach to healthcare data, and a more concerted effort to bridge research and data resource gaps through cross-organizational projects.

Standardize Approaches to Data Collection

Volumes of patient research and care data are generated every day, but the type of information stored can vary greatly between platforms. One participant provided an example of several research groups that collected different information about diabetes from various cohorts of patients and found correlations with different genetic markers. In addition to using different genetic typing platforms with different readouts, some correlations overlapped and some were different. The researchers were able to merge specific aspects of the disparate data and create a common dataset that both confirmed and disallowed some individual findings. Demonstrating the power of aggregating and standardizing data, this case also identified several additional genes of interest only after the data had been pooled.

Similar examples prompted the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to require researchers to pool data collected under NIH grants for the benefit of other investigators. The NIH created the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) to archive and distribute the results of studies, including genomewide association studies, medical sequencing, and molecular diagnostic assays, that have investigated the interaction of genotype and phenotype. The advent of high-throughput, cost-effective methods for genotyping and sequencing has provided powerful tools that allow for the generation of the massive amount of genotypic data required to make these analyses possible. dbGaP incorporates phenotype data collected in different studies into a single common pool so that the data can be available to all researchers. Dozens of studies are now in the database, which by the end of 2008 was predicted to hold data from more than 100,000 individuals and tens of thousands of measured attributes. Hundreds of researchers have already begun using the resource. There is also a movement on the part of the major scientific and medical journals to require deposition accession

numbers when they publish the types of studies alluded to above, in the same way that they require for DNA sequence data. The publications recognize that investigators need to review the data that informed the paper in order to confirm or deny a paper’s conclusions. Other accession numbers are also used when people take data out of a database, reanalyze them, and then publish their analysis.

Lewin provided additional comments on data standardization from the perspective of the American College of Cardiology. The new IC3 Program (Improving Continuous Cardiac Care) is the first office-based registry designed to provide physicians with the most current, nationally recognized best practices for cardiac care. Approximately 2,400 U.S. hospitals participate in ACC registries, voluntarily contributing data and benchmarking their own performance against peer institutions. The ACC is working to standardize the data collected to be able to measure gaps in performance and adherence to guidelines, with an ultimate goal of being able to teach others how to fill those gaps and thus create a cycle of continuous quality improvement. Mandates from Medicare and the states have pushed hospitals to use the ACC registries, but there is room for wider adoption. ACC is working to eliminate barriers in the use of its registries, such as the need for standardization in the way data are collected, the expense of collecting needed data, and the lack of clinical decision support processes built into electronic health records (EHRs).

Lewin also provided insight into the ACC’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR), which is designed to improve the quality of cardiovascular patient care by providing information, knowledge, and tools; benchmarks for quality improvement; updated programs for quality assurance; platforms for outcomes research; and solutions for postmarket surveillance. The FDA’s Critical Path Initiative is an attempt to combine research data from various clinical trials in different ways and to learn more than what was learned in a particular research program, Woodcock said. The FDA has also been working with the Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium to try to standardize as many data elements as possible. But Pfizer’s Slater pointed out that significant roadblocks remain in the effective sharing of clinical data across multiple organizations and platforms. For example, among the trials posted on www.clinicaltrials.gov, for example, shared information can be incomplete, duplicative, and hard to search, and nomenclature is not always standardized. Slater suggested that addressing these issues might improve data resources.

HIV research is an example of how data sharing has worked effectively. Woodcock elaborated on data from multiple trials on CD4 count and viral load. The data were reviewed extensively by multiple bodies, and the FDA was able to advance the field by developing quantitative measures that could be used to guide therapy and drug development. Recently, too, the

FDA has done multiple analyses across drug classes, some of which have been publicized extensively. One set of analyses was of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). The FDA conducted analyses across all the SSRI clinical trials to look for suicidality and excess of suicidality, and found and publicized some evidence of those factors in various age groups. Similar work was conducted on epilepsy drugs. In effect, looking across multiple programs facilitates learning much more than in the past.

Facilitate Cross-Organizational Efforts

As session chair Blumenthal observed, one context for the panelists’ remarks is that the environment for clinical data is much more distributive than ever. In terms of policy, that phenomenon overrides traditional instincts that policy makers bring to bear, which would be to assume that solutions would come by deciding what local, state, and federal governments could do. In a distributed environment, however, such an approach might be framed too narrowly. For example, if the conversation focuses on the personal health record and engages consumers directly, that policy environment is very different from one that would be relatively easy to address by a centralized authority. At the same time, the federal government is a big stakeholder and player in the collection of health-related data. However, the environment surrounding data differ across departments and agencies—the NIH, for example, can focus on promoting data sharing and has a broad mandate for data collection sharing, whereas the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) operates in a much more restrictive environment.

Medicare collects data in each of the four parts of its program: A, B, C, and D. Collected data are used as the basis of paying claims. Data are collected to help improve healthcare quality, for payment purposes, to develop pay-for-performance qualitative information, noted CMS’s Phurrough. Another set of data collection programs are in Medicare demonstration projects that explore a variety of issues and generally examine how different payment systems may affect outcomes versus clinical issues. Data are also collected to develop evidence.

Discoveries at the molecular level provide unprecedented insight into the mechanisms of human disease. Now that powerful genome-wide molecular methods are being applied to populations of individuals, the necessity of broad data sharing in molecular biology and molecular genetics is being brought to clinical and large cohort studies. This has resulted in the NIH Genome Wide Association Study policy for data sharing, and the new database at the NCBI called dbGaP, reported the NCBI’s Ostell. In the course of collecting and distributing terabytes of data, the branch that Ostell oversees, the Information Engineering Branch, has wrestled with questions

concerning which data are worth centralizing versus which should continue to be distributed. For example, the commonality of molecular data might drive the desire to have all related information in one data pool so that a researcher could search all the data comprehensively—perhaps without a specific goal in mind—which in turn could lead to the kind of serendipitous connection that is fundamental to the nature of discovery. At the same time, however, efforts need to be tilted toward collecting only those pieces of data that make sense in a universal way.

The ACC supports the use of national patient identifiers that would enable the tracking of an individual’s overall health continuum across organizations, while preserving patient privacy and bolstering longitudinal studies. Wider adoption of data sharing via registries is within reach and should be encouraged because ultimately it would result in better overall health care. However, strategies need to be developed and implemented that foster systems of care versus development of data collection mechanisms specific to a single hospital. Thus, the ACC is interested in collaborating with other medical specialties, EHR vendors, the government, insurers, employers, and other interested parties.

Providing additional perspective on opportunities for cross-organizational collaboration, Pfizer’s Slater indicated that the pharmaceutical industry is interested in helping to ensure the widespread availability of data to support research at the point of patient care and care at the point of research. In the pursuit of that goal, the industry is interested in ensuring the alignment of data quality, accessibility, integrity, and comprehensiveness. Moreover, the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA) of 2007 will ensure the posting of more clinical summary data. FDA Predicate Rules and FDA 21 C.F.R. Part 11, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and other legislation that are part of FDA and European Medicines Agency standards also help to ensure public access to clinical data. In addition, many companies voluntarily share their postmarketing safety data, Periodic Safety Update Reports, and clinical trials summary data. Data are shared, for example, via the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations, the Clinical Trials Disclosure Portal, the Clinical Research Information Exchange, and Sermo, a community of 60,000 physicians who exchange clinical insights, make observations, and review cases in real time. Woodcock pointed out that scientists have a strong interest in being able to combine data from various research studies, and thus the FDA is very active in promoting data sharing.

The Center for Medical Consumers’ Levin offered general guidance on the subject. He discussed the implicit tensions, such as the tension between protecting private information and sharing it across organizations for specific reasons. Tensions also exist between the federal and state approaches; between the public and private sectors; and between individual and public

health. These tensions play out in the legislative process, which ultimately may facilitate cross-organization information sharing.

Policies on Data Sharing and Research

In addition to identifying opportunities for enhanced coordination to support evidence generation and application, many workshop attendees indicated a broad sense of need to examine the scope of data sharing and research policies, including those that encourage the development of data as a public good and that aim to engage the complexities of patient consent to enhance the research process.

Alignment of Incentives

One carrot that Medicare has developed is that it has required the delivery of clinical data beyond the typical claims data as a provision for payment for certain services. For example, a few years ago the system required additional clinical information for the insertion of implantable defibrillators. Such an approach can provide significant amounts of information if we can learn how to meet the challenge of what we can do with data that have been collected, and merge those data with other sources of data so that data collection can inform clinical practice. The ACC supports investing in rigorous measurement programs, advocating for government endorsements of a limited number of data collection programs, allowing professional societies to help providers meet mandated reporting requirements, and implementing systematic change designed to engage physicians and track meaningful measures.

An influx of regulations as well as an acknowledged need for transparency is prompting the appearance in the public domain of product development and testing data. Nonetheless, we must be careful to ensure data standards, integrity, and appropriate, individualized interpretation. The Center for Medical Consumers, a nonprofit advocacy organization, was founded in 1976 to provide access to accurate, science-based information so that consumers could participate more meaningfully in medical decisions that often have profound effects on their health. The Center’s Levin believes government has a role to play in regulating health care. But as health information technology (HIT) and health information exchange (HIE) move forward, some are concerned that legislation might be pushing us backward, not forward.

Another issue is that data sharing is, in essence, a social contract between individuals and researchers who want to use their data. Patients are told that sharing data will eventually lead to better care. But perhaps

patients do not hear enough about how that is supposed to happen; they are interested in how researchers will use the data to improve care.

Evaluation of Consent Requirements

Establishing the appropriate consent mechanisms for using patient data for research purposes beyond the initial purpose or intention was another area of interest. The current authorities under which the Medicare system collects data are fairly narrow. Medicare has clear legislative authority to collect data for purposes of payment, but also works under legislative requirements to limit that information to the minimum amount necessary to pay that claim. A second authority has to do with quality; Medicare has authority from Congress to collect information necessary to improve healthcare outcomes. Additionally, there is a narrow authority to conduct demonstration projects, solely for the purpose of testing different payment systems. Given those limits, the agency has had to be somewhat innovative, for example, by linking some clinical data collections to coverage of particular technologies.

Woodcock also provided insight into a blood pressure study that had involved automated monitoring. Data from tens of thousands of patients were combined, creating a virtual control group that did not involve time from patients and healthcare systems. In such pooling of data, the FDA has had to address issues of going beyond the intent of the original trials and consent, an issue that will be addressed continuously as data resources grow.

Translation for Engaging the Public

One challenge identified in the workshop was the need to engage the public in data-driven health research through translation and interpretation of the individual and societal benefits of individual health data. Many organizations, including the IOM, pursue opportunities to engage patients and consumers on the issues surrounding healthcare data. Lewin described ongoing efforts to ensure that ACC guidelines, performance measures, and technology appropriateness criteria are adopted in clinical care, where they can benefit individual patients. Although most guidelines are currently available on paper, the vision is to have clinical decision support integrated into EHRs to stimulate conversations between providers and patients. The ACC’s NCDR was designed to research solutions for postmarket surveillance. NCDR strives to provide standardized data that are relevant, credible, timely, and actionable and to represent real-life outcomes that help providers improve care and help meet consumer and patient demands for quality care.

Workshop attendees also indicated that information should be given in language that is more user friendly for patients. Once data are in the public domain, it becomes difficult to control quality assurance and the accuracy with which the information is translated to patients without an acceptable format for providing data summaries.

The FDA plans to build a distributed network for pharmacovigilance. The Sentinel Network would be established to integrate, collect, analyze, and disseminate medical product (e.g., human drugs, biologics, and medical devices) safety information to healthcare practitioners and patients at the point of care. Required under the FDAAA, the Network is currently the focus of discussions with many stakeholders about how best to proceed. One idea is to build a distributed network in which data stay with the data owners, but remain accessible to others.

From a consumer perspective, Levin said there should be a requirement that the data collector do something specific with the data collected, and an evaluation should follow. Such a mechanism can help researchers build trust with patients—by demonstrating the value, convenience, or pay-off of sharing data.

AREAS FOR FOLLOW-UP

Through session discussions and panelist commentaries, several possible opportunities were discussed to continue progress in the development of clinical data as a public good. The following areas were highlighted.

Data Sharing

A workgroup of EHR users and data-storing organizations should be convened to investigate the possibilities of gaining deeper insights through the use of clinical, research, and administrative data across multiple organizations. To start, the workgroup could address issues concerning elements of quality and outcomes, payment and payment system outcomes, and performance and accountability.

Develop Research Methodologies

Bench, clinical, and health services research data have the inherent possibility of being beneficial to multiple investigations beyond initial research intents. Methods are needed to “mix and match” datasets to uncover higher levels of information.

Evaluate Current Policy at All Levels

Because the costs of conducting studies continue to increase, it has become even more important to leverage limited resources to extract the greatest possible benefit. Similar efforts, such as those of dbGaP, have been successful, and lessons learned might be applied in other areas. Although the federal government is one of the biggest participants in the healthcare market, the level of data sharing varies by agency and/or department. Generating national identifier numbers that can be tracked through longitudinal studies from government databases may provide significant insight into the care and care processes provided.

Transparency in Communication

With the increase in data available to measure performance and outcomes at organizational and individual provider levels, many opportunities exist to teach the public how their health information helps themselves and others. Participants stressed the importance of encouraging transparency, while protecting confidentiality, across all levels of the healthcare system. Engaging health consumers in understanding the benefits of aggregated health data through public–private partnerships was suggested as a mechanism for facilitating the conversation with the public.

Increasing understanding of the complexities of the healthcare data environment will involve efforts from all stakeholders. This session of the workshop identified several areas for additional investigation in an effort to stimulate action. Evaluating the opportunities for enhanced coordination through data standardization and multiple-facility efforts was suggested as a key area of interest by workshop participants. Also highlighted was the possibility of examining current policies to align incentives that might encourage data sharing and evaluate patient and organizational consent requirements for participating in data-sharing initiatives. A final area for additional investigation was ensuring that benefits of healthcare data aggregation, sharing, and research are translated for and subsequently communicated to the public.