7

Engaging the Public

INTRODUCTION

Because the public is the key stakeholder in clinical data, efforts to improve data collection and use depend on public understanding and engagement. In addition, a key aspect of facilitating the dialogue between provider and patient is engaging the public in understanding how healthcare data can support individualized disease prevention and health promotion. Too often, however, patient knowledge or expectations are not aligned with the current reality and abilities of data sharing and analysis. This chapter summarizes discussion from the final workshop session, aimed at understanding public concerns and generating discussion on possible means through which the public and their concerns could be addressed. Participants provided insights into public perceptions on clinical care data for research and queried the public’s interest in health data-supported guidance and information. Aspects of the public’s extent of use of clinical data were also examined.

As noted in previous chapters, the public needs to be fully engaged in understanding, generating, and applying clinical data. While the public is aware of some issues and has basic knowledge of the arena, many participants noted that more needs to be done to bring the public fully into the conversation about clinical data, and the public needs to be better informed about what clinical data are and how those data can help them. Papers in this chapter explore how the public is now engaged, and what advances (technical, communication, demonstration of value) are needed to expand their participation in the next-generation public data utility.

Most members of the public do not have a sophisticated understanding of how their clinical data move within or outside an often fragmented system. But, notes Alison Rein, senior manager at AcademyHealth, they do want more and better access to health information about them, their family, and their peers; in particular, they have a strong interest in electronic access to personal health information. In part the public is not as fully engaged in the clinical data utility as it could be because much of the current activity takes place out of the public eye, with data residing largely in the private sector, where commercial interests and other factors inhibit sharing. Unless we overcome market obstacles related to sequestering data for proprietary interests and the technical obstacles related to individual identification authorization and related issues, Rein asserts that a full demonstration of the clinical data value proposition for consumers, both individually and collectively, is not possible. Efforts are also needed to help the public develop a deeper appreciation for research as a public good. As a strategy to build public understanding, Rein supports increased transparency of reporting data that are meaningful to the public and enhancing the coordination and development of registries. In addition, she suggests that policies geared toward a national network for researchers, clinicians, public health professionals—and the public—might generate additional information that could, in turn, inform the public.

Highlighting an opportunity for patients and the public to share individual information, Courtney Hudson, chief executive officer and founder of EmergingMed, describes how giving disease-specific populations increased access to information helps them access clinical trial information and supports a patient-centered search for treatment options based on a patient-generated profile. Although providing access to information is important, Hudson also discusses challenges associated with employing data for secondary uses such as services and systems improvement. Throughout EmergingMed’s 8-year history, Hudson has found that patients and families are interested in informed decision making, and when they receive this benefit, they are generally willing to provide privacy-protected information in return. By contributing to a database and service that identifies similar patients, individuals can anonymously help the public in making decisions. Creating transparency and consequently building trust are also vital when working with individual health information, particularly when engaging the public in broad concepts such as evidence-based medicine. A key distinction in considering the patient’s point of view might be to view clinical data utilities in terms of patient-driven solutions instead of system-driven solutions.

Involving patients in the learning process through personal records and portals is important to patient-centered health care. Today, more personal health data are created and analyzed than ever; however, the degree to

which the data are distributed across delivery, payer, research, and manufacturing organizations continues to increase. Jim Karkanias, partner and senior director of applied research and technology at Microsoft Corporation, notes that with the growth in patient-controlled information, stored in a variety of places, there is a growing opportunity associated with shifting control away from organizations and moving toward a more shared responsibility for information management. For all parties in the healthcare ecosystem, there are benefits associated with easily accessible data aggregated from multiple locations into one patient-controlled location. The connections built based on data aggregation have the power to transform healthcare decision making and improve clinical outcomes. Microsoft’s HealthVault, one of several consumer-centered applications, provides a platform through which the patient determines the depth and breadth of information stored and shared about them.

GENERATING PUBLIC INTEREST IN A PUBLIC GOOD

Alison Rein, M.S.

Senior Manager, AcademyHealth

In many respects, the greatest challenge associated with establishing a medical care data system to serve the public is that such data largely reside in the private sector, where commercial interests and other factors limit sharing. This paradigm has benefited discrete entities, but fails to fully serve the public health interests of the broader U.S. population or promote awareness of how health information can improve clinical decision making for individual treatment. Ideally, the public would express considerable interest in understanding the importance of health information; however, the limitations of current data systems severely inhibit demonstration of the value proposition for consumers—both individually and collectively. This commentary aims to identify some issues for consideration in order to affect public awareness and perception of health data and their use for generating greater public good. The overview will provide what is known about this domain from the public’s perspective and discuss some assumptions and attitudes that may impede progress. Finally, examples will highlight what we might learn from others, and some possible strategies for generating public interest and engagement.

A good place to begin is with public perception of the status quo. The public generally has a limited understanding of the extent to which their clinical data move and are shared—largely, at this point, for payment—within our fragmented healthcare system. The public assumes that clinical information is accessed and maintained by people and organizations who

need it to provide care, yet likely knows little about who (both within and outside the healthcare system) actually accesses the information and for what purpose. Although most covered health providers must give notice of privacy practices to patients at the first medical encounter (usually, a notice in which the content is specified by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, waiver) (Health Information Privacy, 2009), patients likely have little or no understanding of the scope and requirements of the law or what it means for them. Even within the research and operations communities, there seems to be a lack of agreement on the extent of HIPAA coverage. If those in the field disagree or misunderstand elements of HIPAA, it is no wonder that the public should also be confused. Furthermore, there are regulations and statutory requirements beyond the scope of HIPAA (e.g., state laws) about which the public knows even less. Probably even state legislators could not enumerate the variety of different protections and state laws that exist.

Unfortunately, it often takes a chronic illness or significant health event for individuals to appreciate the paradox associated with accessing the volume of clinical data maintained on their behalf by various healthcare entities. Significant clinical, financial, and demographic information can be accessed by numerous parties for a variety of legitimate reasons, yet patients themselves have little or no access to the same information. Researchers wishing to use patient data for public health research are similarly challenged, as many of these data are considered proprietary and in the private domain. An important issue on multiple levels, it will require public education, outreach, and, more importantly, demonstration of value to reestablish the public’s baseline understanding of current uses of health data and to encourage broader support for its application to public-sector research.

Though many point to other industries as examples of successful migrations from paper-based to electronic systems for record maintenance, health care is different in that there is a public expectation of trust and privacy between providers and patients. Unlike grocery store affinity cards, there is more substance to the provider–patient relationship than between the consumer and the supermarket. Additionally, with health information sharing, the potential for irrevocable harm is real. Some believe health care must simply learn from and catch up to other markets; however, this seems short sighted and insufficient given public expectations.

One need only to look at some recent examples of data-sharing practices from other markets to see how such behavior, albeit legal, would be undesirable in the healthcare context. These behaviors include the practices of private entities that sell granular-level cellular and landline phone records of individual consumers; websites that, unknown to individuals, coordinate information from multiple sources and display or sell the aggregated

personal and behavioral data. The extent to which the public knows or cares about such practices is not entirely clear. Some recent experiences suggest that once consumers are aware, tolerance for such practices is low. Facebook, for example, experimented with a model of open information disclosure and received immediate negative feedback from users. In response, the company changed its policy and reverted to a more data-protective approach. By and large, people believe that decisions about how and by whom their personal clinical information can be used (especially by non-healthcare providers) should somehow incorporate individual input or preferences.

Furthermore, there is a growing recognition that many consumers would like and need increased access to their own personal and family health information. Given the challenges inherent in navigating multiple provider settings and the inefficiencies of paper-based records, there is high interest in electronic access to personal health information. Although HIPAA provides for access to paper copies via formal request and a fee, this likely will not satisfy the on-demand expectation of today’s consumers, who have access to other information in real time and free of charge. What is interesting and challenging about the current migration from paper to electronic health records is that no one wants to permit unrestricted access, least of all the individual patient. This type of situation prompts numerous conversations about appropriate policies and incentives both for instituting adequate consumer protections and for deriving optimal value from the emerging wealth of clinical data. This essentially describes a social contract in which both parties, having complete information, actually obtain a desired outcome.

Two major obstacles to realizing the goal of electronic health information access are (1) the current fragmented delivery system, and (2) the free market for data. One promise of electronic health information exchange is that it could help—virtually bind—the various data-holding entities, thereby creating a more integrated care delivery and data management system. However, unless obstacles related to sequestering of data for proprietary interests, as well as technical obstacles related to individual identification authorization and related issues, are addressed, we will not enjoy the electronic exchange of health information that could serve both the individual and public interests.

Until mechanisms are established through regulation or otherwise to compel provider and other healthcare institutions to share data appropriately, leveraging clinical data for the public good will be significantly constrained. The current free-market approach propagates business models that encourage continued segregation of valuable clinical information. What is needed is a more thoughtful approach for determining the types of business models that should be encouraged to flourish because they

could actually stimulate appropriate data sharing. Consider, for example, the tethered personal health record (PHR) system offered by an insurer or provider who refuses to provide data electronically to patients. The rationale supporting this decision is a perceived susceptibility to the competitive advantage derived from owning the data. Another example can be found in many health information exchanges, which sell aggregated patient data to commercial data vendors. Such models enable entities to charge a premium for access to valuable data, which ultimately precludes use by academic and public-sector research communities unable or unwilling to pay for access.

As we work to transition to a new health information paradigm, do we really want to extend models that perpetuate data silos, or do we want to envision another type of business model that promotes sharing and broader dissemination? In this respect, the public and research sectors share a common problem and could benefit from aligning forces and identifying common research areas of interest.

Exacerbating this state of affairs is the fact that patients have very limited access to or control over how their health information is used and shared, and most institutions have little motivation to share patient information for public research purposes. Ironically, patients likely would support use of their clinical information for public research. A recent Markle Foundation survey shows a fairly strong willingness among consumers to share their clinical information for noncommercial research studies (assuming appropriate controls and safeguards).1 The challenge is that most institutions with access to this information do not readily share it for such purposes. Although individuals might be willing to share data in a manner that contributes to the public good, they do not generally have the means to ensure that their clinical data are leveraged for such purposes. In large part this is because most people do not have ready access to their clinical and other health information electronically on demand.

Another issue involves the extent to which the public perceives research and its products as a public good. There has been some discussion of how clinical discovery and science are valued by the public. An entity called Research America regularly conducts surveys through PARADE magazine, which has 74 million readers.2 The survey consistently finds that people believe there is value in clinical research and in supporting research both to sustain our competitive advantage and to advance our own well-being. An entire market exists to promote all the products that emerge from this field (e.g., new treatments for cancer). We do not experience that at all on the public health level. Little, if any, discussion occurs on how registries could

|

1 |

See http://www.markle.org/resources/press_center/press_releases/2006/press_release_12062006.php (accessed August 31, 2010). |

|

2 |

See http://www.researchamerica.org/parade_poll (accessed August 31, 2010). |

identify disease trends and track outcomes among patients on alternative treatments or how clinical data collection at the community level could support public health and wellness promotion activities. These other types of research lag significantly in the level of marketing behind them; this highlights the need for more energy and focus to these areas.

Building Public Support

To build public support, the value of sharing clinical information must be demonstrated. Only limited public demonstrations of this kind are currently used, and even fewer that illustrate the potential impact that might be meaningful to individuals. For example, people might be more inclined to contribute clinical information to a county or other community registry if doing so would increase the ability of local health authorities to identify disease trends or anomalies that could indicate an environmental or other health concern (e.g., asthma related to air pollution, or cancer related to toxic waste). Such an effort could prove highly effective at galvanizing the public and public officials to make policy changes necessary for improving environmental health. The National Academy of Sciences estimates that 25 percent of developmental diseases, such as cerebral palsy, autism, and mental retardation, are caused by environmental factors. The American Cancer Society estimates that one-third of cancer deaths could be prevented through lifestyle and environmental changes, but we are not feeding enough information back to people to highlight existing opportunities and where these environmental factors influence different areas. We do not supply the public with adequate tools needed to make the case for change.

One possible approach to demonstrating the value of research as a public good could be to expand reporting of limited, but meaningful, clinical health data to public health entities. The New York City Department of Health’s effort to have all labs report A1C3 data to the public health department has experienced feedback from those with privacy concerns. The move does, however, serve as an interesting example because the program’s goal is to engage the public health department actively in prevention measures. Furthermore, the program maintains a controlled approach, and only limited data from the public are required. Hopefully what they do with the information can end up having a meaningful clinical benefit for New York’s diabetic community. One likely application for city officials will be to evaluate the impact of the city’s recent ban on trans-fats on A1C data.

Another opportunity to demonstrate the value of research is through the enhancement and expansion of clinical data registries. Today, many registries offer limited accessibility and do not necessarily collect data in

a way that can be useful and meaningful to the public. There is a clear opportunity as we construct registries and future databases to think about public health priorities that could be addressed, as well as ways to stimulate more interest and engagement from the public and produce more value for the consumer.

Multiple organizations have recommended the development of a nationwide health tracking network to help identify, track, and prevent known causes of death (environmental, occupational, and lifestyle/behavioral) and poor outcomes. It could yield information such as geographic and ethnic incidence and prevalence of diseases and inform the public health community, providers, policy makers, and consumers. Currently, the Department of Health and Human Services operates 200 separate data systems, but has little or no means of coordinating across the range of systems. Similar to registries, these systems are not designed to track major causes of death and disability in the United States, even though the data may be compelling and important to the public. In many of these cases, the public is required to contribute information, but may not benefit (or not be aware of the benefit) from these systems. Regardless of what form data efforts take, it is vital to commit more energy and resources to collection, integration, and interpretation of health data in order to better inform policy makers and the public.

Moving forward, we should not underestimate the power and potential of good information in the right hands—including the public. Ideally, we would work to ensure that information resources generated from use of patient clinical data are relevant, valuable, and appropriate. Finally, we should not pit public interests against those of the research community. There is more alignment of interest than there is divergence.

IMPLICATIONS OF “PATIENTS LIKE ME” DATABASES

Courtney Hudson, M.B.A.

Cofounder, EmergingMed

The longstanding tension between an individual’s desire for personalized health information and the population’s interest in healthcare research is exacerbated by scientific advances such as molecular profiling, information sharing on the web, and modern data management tools. Both the public and private sectors are struggling to navigate this logistically challenging landscape to gain medical insights (and sometimes to monetize these insights). Patient-focused clinical trial information services created in the past decade provide a unique perspective on a patient’s view of healthcare research at both the individual and the population level. This paper provides an overview of more than 115,000 cancer patients’ responses to a

paradigm that blends personalized information services with a shared public platform. It discusses how these services have addressed the intersection of an individual’s need for information, access, and transparency with the U.S. healthcare system’s desire for population-based research and data sharing in light of modern data management and data-sharing capabilities.

EmergingMed is an 8-year-old company founded to help cancer patients obtain access to clinical trials as part of their search for treatment options. It is a year-2000 paradigm that allows patients to remain in control: Internet-based searching supplemented with telephone-based support on request. We allow patients to create their own medical record or profile, and they compare their profile to a structured database of cancer clinical trials in the United States and Canada. Today we have a coded database of 10,000 cancer clinical trials, structured by eligibility criteria. Patients coming to our system can, in a matter of minutes, figure out on a preliminary basis whether they are a match for clinical trials in North America.

Our experience gives us a unique perspective to talk to the need, the absolute mandate, to have a patient focus going forward as we think about medical information and its uses for research. Patients in this country are supportive of mining clinical databases for the public good. Overwhelmingly, they believe that it is already happening and they would be alarmed to know that it does not happen.

More than 115,000 cancer patients have created profiles in our system. We have been on the phone with 35,000 patients over the past 7 years. On average, we engage in five follow-up calls with each person so we hear their stories. We hear the successes they have, the challenges they face, and the barriers they encounter. Most of these conversations start similarly—with a discussion that corrects patient misperceptions, allays patient fears, or corrects mistaken assumptions patients have about the healthcare system, what is going to come next, or their personal situation. All of that has been valuable.

When you start with a patient-focused system and then use derivative information so that you have a secondary database, you end up with a very exciting—but complex—situation. Your first priority is serving patients so they can make an informed treatment decision. Through this service, we gather information on the healthcare process, access to care, and outcomes. Day in and day out, our service has to be valuable to patients. The flip side is that you want to do secondary analysis of the information—data mining—not only to run the service better but also to gather insights to improve the system. It is challenging for a system to do two things at once—to process transactions and to run data analysis—and the two systems often collide.

We have had the benefit of being able to create our system from scratch. We are on an Oracle platform. Every module we have, including the call

center software, was newly developed to be integrated so it is a seamlessly integrated software platform. We did not have to contend with a legacy system. Nonetheless, 8 years into our program, the challenges are growing.

Our experience gives us perspectives that merit sharing. First, we find that overwhelmingly, patients are looking for data to make informed treatment decisions. Withholding information available in the public domain would be unconscionable. Patients expect us to share information that might affect their decisions. As we think about ways to use public datasets and aggregate them, it would be extremely difficult ethically to justify policies that withhold information from individuals when they could act on the information. Legacy systems can make it difficult to make information actionable to patients, but nonetheless we need to remember that there is something of a quid pro quo or social contract here. Generally, the patients and families that we work with seem to believe, in essence, that if you will help me with information to make my decisions, I am happy to have you use it to learn things in general, so long as you protect my privacy. As a small company and a private company, one violation of privacy and we are out of business. We do not have an option of violating privacy, nor does anybody else in the private sector.

We believe our patients’ feedback is applicable across the healthcare spectrum. The basic set of assumptions that patients bring start with an assumption that “my doctor will automatically tell me everything that I need to know either about treatment options or what is going on in clinical research and the clinical trial world.” With cancer, however, there are some 400 to 500 drugs in development at any day, and their design, use, and targets are constantly shifting. At any one time there are some 10,000 clinical trials for cancer in the United States alone, and trials are continuously opening and closing. It is simply not feasible for any one person, such as the doctor, to have full command of all of that information.

To take this one step further, if you are a physician who is not literate with computers, you and your patient may have very different expectations about what information you should have at your fingertips. You are also going to have a different set of expectations about what knowledge you should be able to acquire.

One reason we formed this company and this search mechanism was to create a single step (completing a single questionnaire) through which patients could determine which cancer clinical trials are relevant for a specific situation. Patients should be able to determine that in 5 minutes; it should not take 8 hours of random Internet searching through 10,000 clinical trials. Fortunately, finding such information quickly is possible now with modern data management tools.

Imagine physician committees, hospital providers, and healthcare providers making decisions about storing and mining health information if

they are not aware of tools that are available or how data can be stored or structured. Last year an oncology-based physician group was evaluating electronic health records systems for the oncology community. Unfortunately, many physicians and leaders of these committees did not know the difference between free text and structured data and had no concept of long-term implications for data mining and data sharing. The implications for the decision making are striking. The healthcare information technology companies invited to assist this consortium were struck by the relative computer illiteracy of the assembled leadership.

Today patients and the public in general have much more access to some modern, sophisticated data tools outside the healthcare system. Yet we continue to allow healthcare providers to be in the dark—or to be the patient’s sole information provider. The conflict between the two, or the discrepancy between what patients expect and understand and what healthcare providers know and understand, only gets wider. That in turn creates a divide whereby data-savvy healthcare professionals become heroes to their patients, and physicians without those skills not only run the risk of weakening the doctor–patient relationship but also of risk providing less than state-of-the-art healthcare services.

One of the key factors in providing education about clinical trials and cancer research is a focus on educating patients about their diagnosis, their stage, and their treatment history. This paradigm or rubric is identical to the one used by the medical community to assess patients and make treatment recommendations. We find that it remains nearly impossible to educate a patient about a clinical trial if he or she assumes that all cancers and all treatments are the same. If a person does not understand that breast cancer is treated differently from colorectal cancer and uses different research, he or she is not going to understand the specific questions needed for a clinical trial search. If a breast cancer patient does not understand there is a difference between hormone receptor-positive and hormone receptor-negative cancer, she is not going to understand why tests are being done, why treatments are being recommended, or which clinical trials may be an option. We have found that the more one identifies key personal decision points and those key learning disconnects, the faster the patient learns.

Transparency and trust are an absolute requirement in a healthcare system that mines electronic data for health research purposes. The more transparent the system, the more quickly you get a patient’s trust. One of the decisions we made in designing our service was to start with the patient’s perspective. We looked at where patients search for information, knowing that patients search in many places. We created a single system that would serve many types of organizations, including advocacy groups and cancer centers. We operate services for the state of Florida as well as for pharmaceutical companies. We run services for each of them from the

same platform—one dataset, one process, one call center. We were guided by a clear view of the ethical mandate to provide patients with an unbiased, transparent system to help them make informed decisions. We knew we needed to have a conversation with each patient because clinical trial information was prone to misinterpretation and confusion. Hence, customizing the education for each patient was vital.

Virtually every client of ours has some misconception about clinical trials, but nobody misunderstands everything. Most patients have one or two points for which they need clarification, and then they continue their search knowing that the process is confidential and that their information will remain private. We operate with the same standards across all organizations and we never share a patient’s information with third parties. We do share aggregate, deidentified information. We obtain explicit permission from patients up front. We have found that of those people who complete a profile and find a match, 90 percent give permission for us to call them. We are able to do long-term follow-up and tracking through outbound calling. We use each call to get permission for the next call, which also gives us a chance to obtain permission for another use of the data as we go along. It becomes a partnership over time. Patients can opt out at any time, but most do not. Some patients ask us to keep their information in our system, but not call them—they tell us they will call us back when they are ready to use the service again—and of course we respect that. We have stored their data in the meantime, and when we do reconnect with such patients, we pick up where we left off.

Running our program in scale has become cost-effective over time and enables us to track outcomes. We know who enrolls in a study. We know who does not. We know why they drop out of the process along the way. It becomes a rich collection of data. It also lets us provide feedback to stakeholders.

We operate as an independent intermediary. The system requires that the patients refer themselves to trial sites, to actually consider a clinical trial. We do not share patient information with clinical trial sites, but patients can come back to us throughout the process if they need help with logistical information or definitions as the process continues. We are navigators in that respect, but we do not become part of the informed consent process. Consent continues as it always has, at the institution, under the control of ethics committees and Institutional Review Boards.

The informed consent process remains somewhat problematic. It is designed to ensure that the patient is informed about a trial at a site. However, this process does not require that the patient be made aware of other clinical trial options. Competing trials might be available across the street or across town, but the informed consent process does not require this disclosure to the patient. In view of the pervasive fear of being treated like

a guinea pig, we remain concerned that withholding options from patients does, in fact, mean that we are treating them like guinea pigs.

Informed decision making requires full disclosure from the healthcare system. We remain convinced that patients have the right to specific and general medical insights that might impact their treatment decisions and their ability to make fully informed decisions.

IMPLICATIONS OF PERSONAL HEALTH RECORDS

Jim Karkanias, Partner and Senior Director

Applied Research and Technology, Microsoft

Health care is a complex and challenging environment. Massive increases in medical information, in part through the Internet, are making health care one of the most significant hot spots for technology innovation today. Clearly medicine suffers from an information management problem. Control of this information will eventually shift, from a top-down doctor-to-patient model to one in which there is mutual control. For physicians the information control issue is about aggregating data within and across provider organizations. For consumers it is about aggregating data across all of their sources of health data. Ultimately these views will connect for informed health decisions and better clinical outcomes. Today we have more personal health data than ever; however, these data are dispersed over a variety of facilities, providers, and even our own monitoring devices and home computers.

Microsoft is working with our partners to address gaps in the healthcare data management system, both from an enterprise and a consumer standpoint, to enable a more connected, informed, and collaborative healthcare ecosystem. A consumer health platform with specialized health search capabilities is the first application/service and the first step in our strategy that centers on delivering a platform that puts users in control of their information so they can access it, store it, and use it however and wherever they want it.

Microsoft recognizes that sensitive health information should be protected by strong policies and clear operating standards. In consultation with consumer privacy experts, we developed and implemented industry-leading Health Privacy Commitments for ourselves and stringent privacy principles for solution providers, developing on the Microsoft HealthVault platform. We are committed to making a difference in health care, and we firmly believe in software’s ability to make a positive impact on the healthcare ecosystem worldwide. However, no one company can resolve health and data issues alone. Transforming health care is a complex problem with no

easy answer and certainly no quick-fix solution. We are taking the long view in our approach—it will be a marathon versus a sprint.

In terms of data sharing, we are all quite familiar with the Gordian knot of problems with data use, privacy, and the associated tensions. Meetings such as this one sponsored by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) help us begin to identify the elements of answers. That reminds me of a quote from William Gibson, the science-fiction author, who said: “The future is already here. It is just not evenly distributed.”

Microsoft has engaged for the long haul in the process to improve health around the world and connect communities for positive health outcomes. The ecosystem in which Microsoft’s HealthVault operates is meant to be a comprehensive platform in the center of this environment. It is named HealthVault because it serves as a vault for personal health data. It is meant to focus on the consumer.

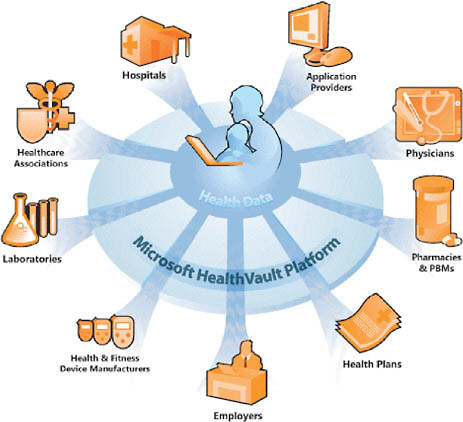

We have an illustration that provides some detail about HealthVault (Figure 7-1). It covers every detail of what goes on in the hospital, what

FIGURE 7-1 The HealthVault ecosystem.

NOTE: Reprinted with permission from Microsoft.

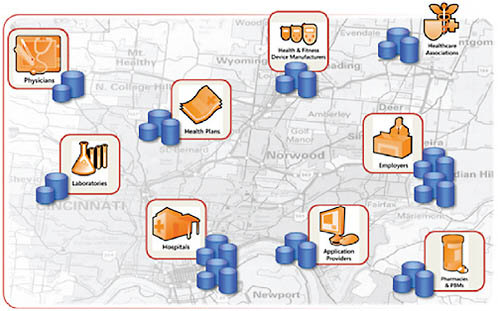

FIGURE 7-2 Silos of health information.

NOTE: Reprinted with permission from Microsoft.

might go on in the wellness side of the equation, what an employer might need to see, drug fulfillment requirements, and all the various medical devices in a patient’s life. An important aspect of HealthVault is that it helps to collect the data that one might want to store and share with others. The notion here is that the consumer is in charge.

We first shipped HealthVault last year. The year before that we launched a product named Amalga, an enterprise hospital environment software that is meant to automate all the various activities in a hospital. (MedStar actually helped to develop that; we produced the software framework.) Obviously, many sources of information are in the system already. The problem is that too many sources of information in the system are silos that individually provide various important aspects (Figure 7-2). Integrating all of these silos is the key. There are many ways to achieve that—an overly centralized solution is just as difficult as not having a solution at all; a democratic-style solution is a different model; and so on. The question about addressing this as an information platform needs to be discussed.

The Consumer at the Center of the Equation

If we accept the premise that consumers are at the center of this equation, and that the information, activities, and processes that they are wor-

ried about in their healthcare journey all affect them anyway, they are a logical aggregator for this information, if only they could have a platform that would allow for that aggregation to occur. That is what HealthVault is. These various silos, through devices or through applications, allow data to flow into an environment that the consumer controls and owns. These data are the consumer’s data.

HealthVault is an application platform. We do not propose to build these applications, but rather want to create an ecosystem of integrated software vendors to develop applications and devices in this environment. Many partners are already hard at work creating a set of services to support this activity. The folks who have put together these kinds of things in the past have often seen their efforts stymied by having to create all the vertical infrastructure to integrate across the various silos, creating firewalls or filters, or all of these things that our platform will help provide. The notion is that you can copy data from various sources and aggregate them for yourself in your HealthVault account as a consumer.

It is important to stress that HealthVault itself is not a PHR. It is the environment that allows a PHR to exist to be created from those pieces of data. Other providers of wellness data, such as body mass index calculations, or condition management devices such as glucometers that generate data and flow it into the system, will have their own applications that leverage the platform.

Other applications may also benefit the consumer. For example, a weight management application may benefit from a connection to an EMR or to cell phone data that measures location over time and correlates with pollen counts to which a person with asthma may have been exposed.

We do not intend to be the entity that stores this data, but rather see our role as facilitating the flow of information. PayPal, the online payment service owned by eBay, is an interesting analogy in the way it enables transactions to occur and accelerates all the convergence that we recognize must happen in this environment, such as accessing funds without revealing credit card numbers. So just as PayPal accelerates the storing and sharing of financial data, HealthVault accelerates the storing and sharing of health data. All of the complexity of dealing with that data securely and privately acknowledges the regulations that are in place, or connects to pharma, or the clinical trial provider, or the recruiters, or those who provide advice about a condition. All of that difficulty is handled by the platform, and only a relatively small amount of effort compared today’s development activities is necessary to create that functionality.

Built into this platform is the notion of privacy and security. You cannot add that later; it has to be part of the environment. It needs to be adhere to industry standards. We are not charging for it—it is a free platform meant to enable and activate the paradigm shift we think can occur

when placing the consumer at the center of the equation. The consumer is highly motivated to focus on these pieces of information and aggregate them. We want to enable that. Appropriately, therefore, privacy and security are integral parts. We took a lot of time to determine how to make these factors as solid as possible given state-of-the-art technology. Again, the consumer is in complete control of the data. There is no way that that cannot be the case.

We think there is a notion of a family health manager, typically the mom who is worried about keeping her family safe. A lot of this activity goes on already; it is just done manually. The scenarios can be segmented further along a continuum. The complexity of the application increases, as does the user’s engagement. Consumer applications fall into three primary segments: primary prevention, secondary prevention, and acute care. Patients who are in the primary prevention wellness side of the equation, where the applications are fairly straightforward, are engaged according to their own self-motivated needs. They are maintaining their health and wellness. Then we move to the more complex patient, who might be hospitalized or be living with a chronic disease. Finally, we see uses in acute care, among hospitals, group practices, and physicians.

Today we are in a reactive model. In terms of the economics of a health-related event, showing up at a physician’s office has been the first step. A cost is associated with that event, and the cost spikes each time things get worse. We believe patients would prefer to be proactive in managing their health, and that is the model we are trying to create. They would avoid repeated costly visits and, instead, have daily in-home monitoring to allow for proactive measures to be taken to the extent they can be detected. This might play out in the use of a spirometer to encourage patients to inflate the lungs and thus avoid pneumonia, or some other device to manage a condition, and making that data available to the clinicians the patient authorizes. If that kind of approach can drive proactive management of care, how much better has the system become by definition? You can extend these to other scenarios. What if you had devices that were much more advanced and could detect a condition or other event and issue an alert? Again, that is all possible with this new technology.

REFERENCE

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). Health Information Privacy. http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/consumers/noticepp.html (accessed October 12 2009).