4

Case Studies in Transformation Through Systems Engineering

INTRODUCTION

Creative approaches are necessary to meet the Roundtable’s goal that “by the year 2020, 90 percent of clinical decisions will be supported by accurate, timely, and up-to-date clinical information and will reflect the best available evidence.” In this section of the workshop, guidance was solicited from organizations both within and outside health care that have achieved successful elements of transformation. Presenters provided accounts of their achievements and offered insights into their organization’s transformation through approaches to systems engineering. The aim was to stimulate the sense of what might be possible in health care through the lenses of three industries in particular: airlines, manufacturing, and health care.

For practitioners seeking to reform various aspects of health care, good models of the applications of principles, tools, and practices from systems engineering can be found in both business settings and healthcare systems. Four veterans of such work described their experiences to the workshop audience, discussing how complex enterprises have successfully developed systems-oriented procedures and integrated a systems orientation into practice. The session investigated how systems engineering has been successfully applied in the three industries and sought to understand which lessons might be applied to the transformation of the sociologically and technologically complex healthcare sector. Implicit in the discussions was the importance of bold leadership in driving reform, the imperative of having clarity of mission, the merits of developing strong metrics and sharing results widely, and the value of investing in people.

John J. Nance, founding member of the National Patient Safety Foundation, reported on a rich set of systems reforms that has been achieved by the aviation industry. Nance highlighted strategies that go beyond well-honed aviation practices, such as checklists and methodologies in crew resource management (CRM), which could be of benefit to healthcare systems. He described how systems engineering has been applied in sophisticated feedback systems for reporting and learning from mechanical problems, the development of robust computerized processes for many aspects of daily operations, and standardization that has been applied widely across airline operations. He also described systems that have been built around the assumption that human beings can never be perfect, and thus they are designed to be capable of absorbing anticipated levels of human failure. The discussion also touched on the importance of applying systems thinking to training, on the value of improved communication among staff at all levels, on the usefulness of minimization of variables, and on how systems interact.

To demonstrate how systems thinking can help effect deep-set, meaningful, and lasting organizational change, Earnest J. Edwards, formerly of Alcoa, Inc., focused on improvements in a specific business practice, the financial close process. Detailing how a similar change effort was applied successfully in a leading corporation, a federal government agency, and a community hospital, Edwards demonstrated how systems thinking can help organizations lower costs, improve quality, and leverage systems to yield better information for use in decision making. Moreover, he suggested, undertaking the process of change can itself help staff learn how to become solution-oriented change agents with a focus on the future—and thus become more vital partners in the enterprise, with an expanded role in strategic decisions.

Kenneth W. Kizer, chair of Medsphere Systems Corporation, began by describing the condition of the veterans healthcare system in the early 1990s. Managed by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), it was considered inefficient and indifferent to patient needs. Kizer described how, through a concerted reengineering effort, the VA healthcare system was transformed into a model healthcare provider. Kizer described how the VA overhauled its accountable management structure and control system, integrated and coordinated patient services across the continuum of care, improved and standardized the quality of care, improved information management, and aligned the system’s finances with desired outcomes. Kizer suggested that similar interventions could help other healthcare enterprises achieve new levels of success.

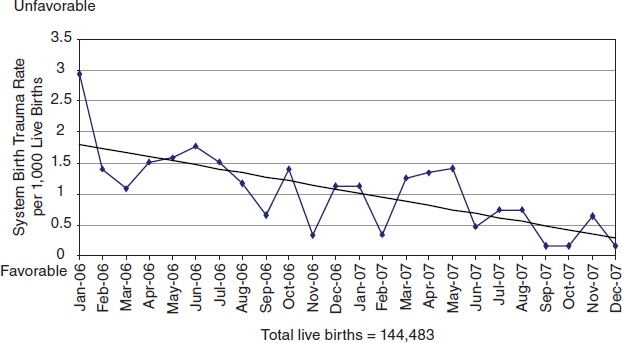

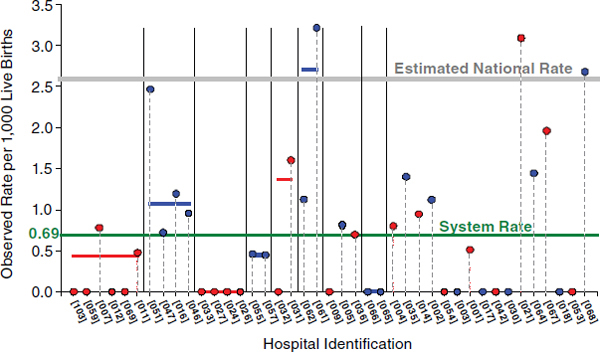

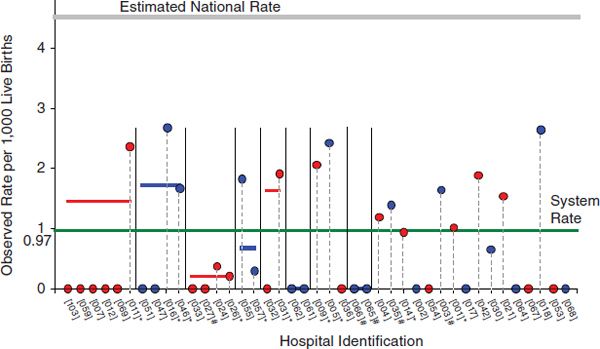

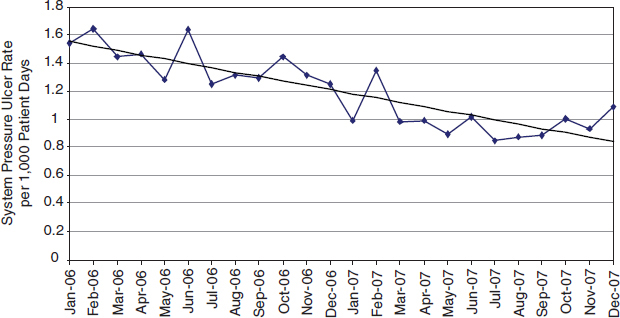

In the final presentation described in this chapter, David B. Pryor, chief medical officer of Ascension Health, discussed the clinical transformation of Ascension, which is the largest not-for-profit delivery system in the United

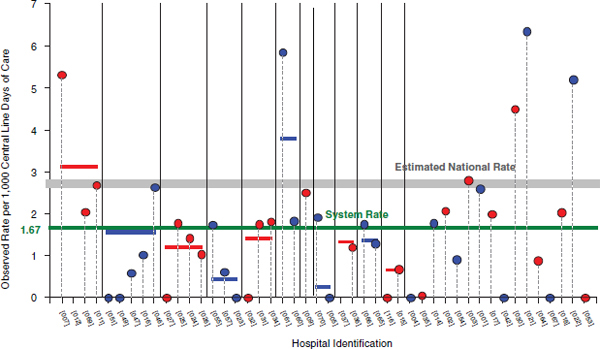

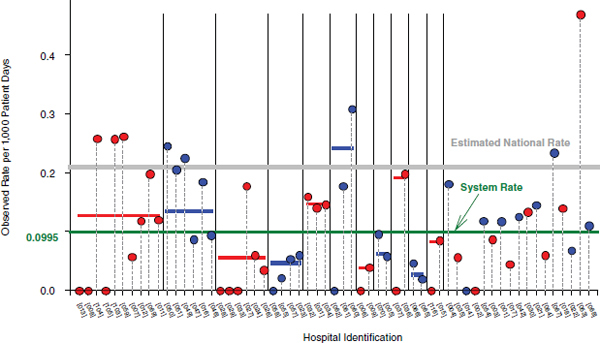

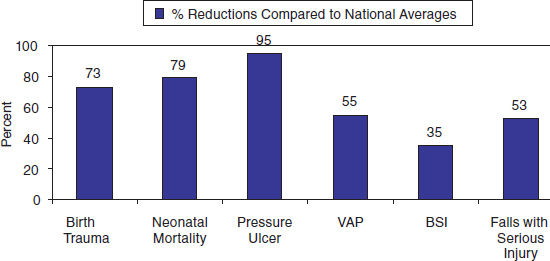

States and the third largest system overall after the VA and the Hospital Corporation of America. Pryor described Ascension Health’s “Call to Action,” a program designed to reduce preventable injuries or deaths as well as to achieve certain other measurable goals. Pryor outlined a systems process for defining challenges, strategizing opportunities, focusing on goals, implementing action plans, and testing and measuring results that allowed Ascension Health to reach its goals. Pryor said that through this process Ascension Health was able to simultaneously realize outstanding clinical outcomes, achieve promising trends in financial outcomes, and develop new metrics that influence quality across its entire system.

AIRLINE SAFETY

John J. Nance, J.D., National Patient Safety Foundation, American Medical Association

Although it would be hyperbole to say that the solution to much of what troubles American health care can be found in engineering disciplines, I truly believe that engineering and the engineering community can provide unprecedented expertise and contribute substantially, if not pivotally, to the national task of creating order out of the chaos that characterizes American health care today. This is not to demean health care. I am merely being frank about the reality that a cottage industry based on individual physician autonomy has grown to unmanageable proportions on a thoroughly inadequate organizational base. A century ago, hospitals were few and far between, and the remarkable advances in medicine and equipment achieved since that time have essentially been forced to fit the archaic mold that was established in that period. And the system clearly is not working in terms of either the reliable and safe delivery of the best care or the best value. Engineering philosophies, approaches, and discipline are not a cure-all, but where medicine has been unable to formulate a structural approach to the problem through traditional methodologies, new thinking from external disciplines may be of great benefit.

American health care needs to find a balance between two extremes. At one end of the spectrum is the clearly inadequate 19th century model of the individual doctor and the hospital as a sort of market that provides beds, nurses, and lights. At the other end is a rigid, mechanized approach to health care whereby autonomy is limited to small differences in the techniques physicians may use within the context of inflexible procedures and full employment directly by healthcare providers. Obviously, neither extreme can take advantage of both the remarkable advances in science-based medicine and the dexterity, intellect, and analytical abilities of individual physicians (as well as the human caring-based attention of nurses as the

bedside eyes and ears of the physician). One extreme needs no engineering, while the other would overuse both systems engineering and the lessons from such fields as airline safety. A careful balance is needed that preserves the humanity and individual expertise of healthcare practitioners while providing an efficient and workable structure that serves the primary goal of doing the best possible job for patients and having physicians enjoy their profession.

These introductory points are important in any discussion that looks beyond medicine for answers, and this is especially true with respect to the applicable lessons from airline and aviation safety. The application of those lessons, as well as a brief look at how U.S. airlines have achieved a nearly perfect safety record, requires a basic understanding of the strategy employed and not just the tactical details of individual training programs and methods.

My professional background melds aviation and medicine and includes 18 years of experience in translating to health care the surprising human lessons we were forced to learn in the aviation industry (along with lessons from other fields such as nuclear power generation). In summary, by the late 1970s, aviation had reached the limits of its ability to improve safety significantly through merely mechanical and procedural means, and it was only by applying lessons from the human factors and performance disciplines that the airline industry was able to take the final step toward zero accidents and incidents.

In many ways this nearly unnoticed transition can be characterized as moving from a reliance on the principles of mechanical and aeronautical engineering to an acceptance of the principles and benefits of human systems engineering. The sometimes difficult transformation from a myopic focus on mechanical reliability to a focus on overall systemic reliability was guided at every step by the discipline engineering brought to bear in helping the airlines accept the realities of the potential for human failure and the resulting ability of airline safety leaders to impose better order and function. In other words, we finally had to stop believing that the only bulwark against accidents was the fine-tuning of our machines and black boxes and admit that, when even the finest airplanes could be flown into a mountain by a well-trained but confused and distracted aircrew, the failure modes of the human being would have to be addressed. The important point for the present discussion is that the same elements of transition are needed in American health care—and even more dramatically so because the procedural/mechanical side and the human systems engineering side of health care are equally undeveloped and undisciplined. To help explain why this is the case, let me focus on the experience of aviation.

For perhaps 10 years now, there has been a growing realization that aviation’s experience in transitioning from a high-risk industry to a low-

risk, high-reliability industry has some applicability to American health care. The problem has been oversimplification in translating that message. People in both aviation and medicine have believed that the best lessons the aviation industry can offer to health care are simply a few specific programs and methods, such as CRM courses and checklist procedures.1 The assumption was that such tactical solutions could be transferred intact to the medical arena and yield the same dramatic improvement they achieved in aviation. In reality, while the principles of each of those tactical measures can benefit medicine if properly translated and adjusted for the realities and complexities of medical practice and application, a far richer body of lessons and benefits can be derived from aviation’s experience.

Aviation, of course, is inherently no smarter about preventing disasters than is health care. But the fact that our failures were both very public and very frightening to our future customers and the fact that our death tolls reached large numbers with each major accident meant we had to address the last remaining unsolved cause of airline accidents—human mistakes— decades before health care had to face that same issue. We simply did not have the luxury of waiting for improvements to evolve. We had to figure out why dedicated, intelligent, and well-meaning air crews continued to fly mechanically perfect airliners into the ground or otherwise cause horrible accidents—so-called “pilot error” accidents.

In truth, the safety challenges the airline industry faced through the 1970s were perplexing. We had enjoyed great progress in airline safety from the dawn of commercial aviation in the late 1920s through the dawn of the jet age in the 1960s and into the 1970s. In fact, the curve of major accidents plotted against time had been declining at a remarkable rate as the machines were greatly improved, instrument flying became sophisticated, and the new jet engines introduced far greater reliability. That descending curve also represented greatly decreasing passenger fatalities, and while our metrics left something to be desired, we clearly improved by many orders of magnitude over time as mechanical failures triggering accidents became increasingly rare. Boeing, McDonnell Douglas, Convair, and later Airbus all learned how to build significant redundancy into their products, helping to pioneer the principle that no single or even dual failure of any component should ever result in the loss of control of an airplane. In fact, one of the earliest instances of human factors engineering was the decision, based on an understanding of the human propensity for failure, to have at

![]()

1 CRM is a discipline that recognizes that no one leader, captain, or physician is capable of perfection. Therefore, the best defense against disaster due to human error is to utilize the professional talent and cognitive abilities of all participants through collegial communication that can be codified, taught, and required.

least two pilots in each commercial cockpit specifically to provide a human backup system. For the most part, the positive safety trends—albeit mostly mechanically based—continued into the 1980s and 1990s. With only a few exceptions—a faulty cargo-door latching mechanism (United 811, 1989, south of Honolulu); a destroyed engine and flight control system in a United DC-10 flight ending in Sioux City, Iowa, in July of the same year; the loss of the upper forward fuselage of a highly corroded Boeing 737 belonging to Aloha Airlines south of Maui in 1986; and the loss of TWA 800 due to a fuel tank explosion years later near Moriches, New York—by and large it had become a rule that when an airliner was destroyed, with or without loss of life, the primary contributing cause was human error. Indeed, records show that this was true in more than 90 percent of cases. Even the term “pilot error” (which implies a professional discretionary mistake such as making a conscious decision to violate the rules, with catastrophic results) was criticized as inadequate because being human inevitably implies being able to make errors that sometimes cause accidents.

By the 1970s, the trend curve for major airline accidents, especially in the United States, had flattened and was lying on average just a few points above zero. But it refused to descend to zero. In other words, while airline flying had become remarkably safe and reliable, especially with respect to mechanical accidents, no amount of industry effort, Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) pressure, or pilot training could completely eliminate human-caused disasters, and no accelerated application of the traditional engineering solutions appeared to improve the situation.

In the 1980s, however, a true revolution, quiet and unnoticed, began to change the equation. As a direct result, 16 years later the airline accident death rate for U.S. airlines finally hit bottom and remained at 0 for nearly 5 years—a stunning achievement. Although this 5-year 0-accident record ended with a crash in 2006 in Lexington, Kentucky, the passenger death rate in U.S. service has remained flat since then (Levin, 2009). This achievement was due to a recognition of the fact that aviation is a human system and that humans will never be able to operate without making mistakes. In other words, the path to perfect safety was through the process of building a system that fully expected and was ready to absorb human mistakes. The engineering-based disciplines that evolved in the airline business (and aviation in general) from that pivotal recognition are loosely known as human factors engineering, but they include systems engineering as well and borrow heavily from sociology, physiology, and behavioral science.

Before the industry realized in the early 1980s that it had never really addressed human failure (except to ineffectually order humans not to fail), there was a growing silence about the prospects of ever fully eliminating passenger deaths and disasters. It was quietly acknowledged that a certain number of accidents might be the cost of doing business, that accidents

might be inevitable in a system that each day sent as many as 3,000 flights around the country and carried many tens of millions of passengers each year. Moreover, as the airlines came under tremendous cost pressure during the early 1980s because of deregulation and cut-rate competition, established airlines began looking desperately at ways of reducing costs. In that environment, concern grew that massive new investments in maintenance, training, and electronics would be needed to realize even an incremental improvement in safety (given that there were already so few crashes). This situation did little to generate enthusiasm for expanding safety measures or investing in new disciplines such as CRM (which was in its infancy at United at the time). The heavy price of small improvement, in other words, furthered the idea that a small number of accidents might have to be accepted as the cost of having an airline system. Of course, this was not an illogical argument at that time. In fact, one major airline executive rather infamously replied to the question of why his airline did not spend millions to establish a safety department by saying: “We don’t need one. That’s why we have insurance.”

Before the emergence of human factors in the 1980s, the airlines had successfully applied systems engineering principles in many ways (sometimes without labeling them correctly) to develop high levels of mechanical and operational reliability. Across the industry, we had developed sophisticated feedback systems for learning rapidly about mechanical problems, systems that included the so-called Airworthiness Directives issued by the FAA (the strongest type of legal directive the FAA can issue to effect mechanical changes), as well as less urgent service bulletins transmitted to the entire commercial aviation industry within and outside the United States. In addition, there was a broad range of methods by which the airlines could communicate with each other, the FAA, and the National Transportation Safety Board, including a number of task forces and special industry groups working voluntarily with the government on problems of special concern (e.g., the revelations in the late 1980s about the susceptibility of aircraft structures to accelerated corrosion and fatigue in high-salt environments following the Aloha accident of 1986). To a certain extent, those systems have all now matured (along with individual reporting systems such as the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Aviation Safety Reporting System), to the point that any significant problem discovered in commercial aviation can be fully discussed and communicated to every operator worldwide within hours. Aviation, in other words, worked hard to learn serious lessons about maintenance and training once the FAA pushed for airline safety by working with, instead of against, the industry.

In the same period of the 1970s through the 1990s, under Part 25 of the Federal Aviation Regulations (14 Code of Federal Regulations 25), the major airline manufacturers developed a level of redundancy in their designs

such that the anticipated failure rates of most of aircraft and components had a long string of zeros to the right of the decimal point before a nonzero digit appeared. Through backup systems and preventive maintenance (pulling and replacing or overhauling components long before their first anticipated failure range), the so-called “dispatch reliability” of airliners exceeded the most optimistic expectations. In addition, airlines developed processes for the computerized tracking of maintenance, parts, and all operational elements—including crew scheduling, reservations, ship scheduling, dispatch, and coordination of all functions—optimizing the rapidly developing capabilities of computers. The airlines achieved computer-assisted standardization of nearly everything done in the maintenance hangars, in the cockpit, and even in operations. All of these elements were honed continuously because they were the most cost-effective methods of doing business. Airlines realized that in a heavily competitive environment, they simply could not afford the type of public relations catastrophe that any major accident would cause. The costs to an airline’s reputation would be far beyond the direct costs of any such accident.

All of the mechanical and computerized systems were largely in place by the end of the 1970s, but, as previously noted, crashes still happened, usually because of human failure. In 1982 an Air Florida Boeing 737 crashed on takeoff in a snowstorm in Washington, DC, killing all but five of those aboard, who were rescued from the icy Potomac River. There was nothing wrong with the airplane. In 1985, an Arrow Air flight chartered to bring U.S. troops from the Middle East to Kentucky crashed in Gander, Newfoundland, killing all 256 people aboard. Although there is still controversy about that crash, it was attributed to the crew’s departing with ice on the wings—again, there was nothing mechanically wrong with the airplane. A Northwest Airlines plane crashed in Romulus, Michigan, in 1987 because of the pilot’s failure to extend the flaps, and all but one died. A year later, a Delta flight at Dallas–Fort Worth Airport also tried to take off with the flaps up and crashed, killing 17 people. The flight crew survived, and they were astounded at the National Transportation Safety Board’s finding that all three of them had missed clear signs that the flaps had not been extended. Three highly trained, highly qualified human beings had caused a major accident, and all three had “seen”—and were willing to swear they had seen—instrument indications that the flaps were in the correct position (15-degree extension). The flaps were not in the correct position.

Given events such as these, the airline industry realized by the early 1980s that such tragedies would continue unless it adopted radically different practices and, for the first time, addressed not just advertent human failure but wholly inadvertent mistakes. To that end, the industry had to do more than adopt major changes; it had to change its philosophy and, most important, to change the entire culture of airline piloting.

Many who look at the aviation industry’s excellent safety record today erroneously think it is simply the result of engineering successes based on the mechanics of the operation, on systems, and on getting people under control and completing more and more checklists. In fact, even some members of the industry are unaware of the cultural revolution that transformed our ability to prevent accidents due to human mistakes. More to the point for this workshop, the changes I refer to as a renaissance in thinking during the 1980s and 1990s have helped us create a new paradigm that can, as many have realized, be transferred to health care. In fact, I and many others have been doing exactly that with solid success for a number of years, primarily by focusing on training healthcare professionals in the discipline of how humans fail and what can be done to create a human system that can prevent those failures from hurting patients. That training is completely counter to the traditional, autonomous approach to health care, especially in relation to physicians, in holding as a fundamental tenet that although individual humans—including surgeons—are incapable of achieving perfection, interactive and collegial teams of humans can do so. Indeed, this is the primary legacy of the CRM revolution in airline cockpits, where we have saved countless lives and aircraft in the past 20 or more years by requiring more than 1 human mind to weigh in when something appears amiss and using a teamwork approach based on the common goal of flight safety to approach self-correction and safe operational decisions. Eliminated in such an atmosphere is the angry autonomous leader who disciplines a subordinate by berating, belittling, and ignoring that individual just for speaking up. Gone as well is the situation in which a subordinate has the key to save everyone but cannot pass it to the leader.

Health care today and the airline industry of yesterday are remarkably parallel in that every physician, nurse, and other healthcare professional is trained, essentially, to be perfect and never to make mistakes. Worse, the system is built the same way aviation was—on the expectation of human perfection, with few if any buffers to allow for major human mistakes. In the airline industry, thousands of work-years of engineering had been devoted (with great success) to providing backup systems for even the most arcane failure modes, but when it came to engineering for human failure, the approach taken was simply to order the human not to fail. Equally appalling in light of what we now know was the lack of emphasis on human-to-human relationships as the platform for true communication, coordination, and self-correction. Similarly in medicine, there is traditionally no expectation of human error in good doctors, nurses, and pharmacists, so there appears to be no valid reason for having backup and buffer systems to absorb mistakes.

The lesson from the airline industry, then, is that buffers against normal human error are a prime safety component in any human system. Of

equal importance is the reality that the healthcare culture, as previously was the case with the airline culture, includes an expectation of hierarchical autonomy that is challenged by any subordinate speaking up to report a mistake or concern. In the airline industry, subordinates’ sensitivity to the feelings of a senior created a culture-based reluctance to point out concerns, problems, or even impending disasters lest the leader become angry at the suggestion that he or she was in error. Leaders, after all, are trained never to make mistakes. But that left only one mind operating in an airplane (or an operating room), while the other qualified professionals sat in silence, even (in the airlines) if the captain was a gentle individual who wanted to hear from his or her crew. This situation kept us from improving safety levels and preventing that last tier of human mistake-driven accidents.

Perhaps the most important experience the airline industry can share with health care is its realization that no human can be perfect and that no team can function as a team without collegiality and mutual respect. We proceeded to build a system around those assumption, constructing buffers and backups for all reasonably anticipatable human failures that might otherwise lead to an incident or accident. And history shows that we have succeeded.

We learned that a safety system has three distinct tiers. Tier 1 encompasses all the training and indoctrination and agreed-upon or imposed professional methods, such as checklist compliance and “time-outs,” that are designed to prevent human error. Understanding that some human error will occur despite our best efforts at standardization and training, we then must construct Tier 2, comprising those buffers and backups that will catch and cancel out the effects of human error and latent system failures. Finally, Tier 3 reflects the realization that even after accomplishing highly effective work in preventing and then screening out the effects of mistakes, we will still occasionally experience catastrophic failure unless we enter every operational sequence expecting a 50 percent chance of failure. With this expectation and through collegial teams whose members have no hesitation in communicating with each other for the good of the mission, we construct a systemic approach that ensures our leaders are ready and willing to consider even the most tenuous concern as potentially valid and “stop the line,” or hold off on the operation, or abort the takeoff until the team and the leader are sure that safety is not threatened. Thus, either a junior flight engineer or a new circulating nurse would get an instant and serious audience by saying, “I’m not sure, but I think something’s wrong,” rather than having to overcome a group presumption of normalcy. That one change—the Tier 3 approach—can be the final key to constructing a system that protects against catastrophic patient injury or death from preventable medical human mistakes. But to institutionalize such procedures requires a systemic approach that is foreign to the American healthcare

experience, which is why looking to the engineering community for help is so important.

Human beings fail in three basic ways—by making mistakes in perception, assumption, and communication. Perception failures include, for example, a flight crew’s failure to recognize that the aircraft’s wing flaps are not properly extended for takeoff. One mistaken assumption caused an accident in 1977, when two pilots assumed their Boeing 747 was cleared for takeoff when in fact it was not. Another 747 had missed a turn and was sitting sideways on the runway ahead, unseen in the fog. The decision to start the takeoff was a human mistake nurtured by a poor cockpit culture. That day it resulted in the loss of 583 lives. The third human failure is mistakes in communication, a human propensity shared by health care and aviation. Approximately 12.5 percent of the time in human verbal communication, people who otherwise understand each other fail to do so in that instance. The old phrase “I know you think you understood what you thought I said, but I am not sure you realize that what you heard wasn’t what I meant” points to the universality of misunderstanding. We have learned, however, that reading back a clearance or a medical order can reduce the potential for mistakes to below half a percent.

Aviation had to learn these basic failure modes instead of fighting to deny them or ordering them to not occur. We had to learn to inculcate the expectation of such failures in everything we did. So, too, must health care. But to accept these realities operationally and culturally and integrate them into health care (with its largely autonomous tradition), we need a structured, engineered framework within which such approaches as the minimization of variables, collegial team communication, and the three tiers discussed above can be deployed as standard operating methodology. Equally important—and not just to avoid the charge of creeping cookbook medicine—is that the resulting structure must nurture physicians in using their cognitive, analog, diagnostic, and surgical skills to do what checklists, machines, and procedures alone can never accomplish. By finding the proper balance, one can create a system that enables humans—through technology and enlightened methodologies—to practice what they do best—apply judgment, skill, and reason.

We cannot incorporate an expectation of perfection in a human system without creating and nurturing disasters. We cannot fail to accommodate human attitudes, feelings, or physiological limitations without perpetuating a societally unacceptable level of patient injuries and service quality. What health care needs from the applied and unique expertise engineering can provide is a structure that legitimizes and inculcates known best practices, eliminates the need or latitude to reinvent each procedure, and provides the best possible operational buffers against inevitable human fallibility, while

at the same time providing the latitude within which healthcare professionals can practice with caring and engaged attention.

This exploration of looking to the engineering community to assist health care probably heralds the most important advances in changing how we have traditionally thought of the problems of patient safety, service quality, and healthcare delivery since we first began to recognize that we have a national problem with what George Halvorson, chief executive officer (CEO) of Kaiser Permanente, calls our nonsystem. To bring order out of chaos, we need help that goes beyond the traditional methods applied in the past. In aviation, both mechanical and systems engineering provided the keys both to building reliable airplanes and to staffing them with imperfect humans who, working together and as colleagues able to communicate without barriers, could accomplish what a single commander could not. If we keep that in mind and borrow liberally from other disciplines, we can engineer a system that works, that works safely, and that can be financially sustainable.

ALCOA’S REORIENTATION: STREAMLINING THE FINANCIAL CLOSE PROCESS

Earnest J. Edwards, Alcoa, Inc., Martha Jefferson Health Service

World-class organizations have been breaking traditional paradigms and achieving real value by adding to their operations the use of finance organizations that embrace and act on the following five key characteristics:

- emphasizing high efficiency, low cost, and high quality;

- effectively leveraging systems and providing better information for decision making;

- becoming solution oriented and change agents;

- focusing on planning the future and not reporting the past; and

- becoming vital business partners with an expanded role in strategic decisions.

Although health care is different from most industries, it could benefit by embracing these same characteristics and using finance as an example of major change for other areas to follow. During the major change that took place at Alcoa in the 1990s (as directed by then-CEO Paul O’Neill), finance and other staff groups played an integral role in the transformations that were required of all business units and staff departments. Two of the guiding principles that fostered the improvements achieved were to make quantum-leap changes so as to close the gap in the best-in-class

where such a gap existed and to insist on “no opt out” by any function or department.

This paper reports on the streamlining of the financial closing process, which was a quality cycle-time reduction project. This project resulted in significant cost reductions and enabled other finance projects to make more rapid changes with greater benefits. This was especially true in the subsequent period of Alcoa’s rapid growth strategy. The accelerated closing project also provided more timely information for business decision making, served as an example of how to improve routine processes in a major way, and was a major motivating force in the company. A similar project was undertaken and completed successfully in the U.S. Department of the Treasury, again under O’Neill’s leadership, and more recently, another such project, yielding many of the same value-adding benefits and direct cost reductions, was carried out at the Martha Jefferson Hospital. This is a worthwhile leadership project that can introduce major change to any organization and serve as an example of what can be done with commitment, focus, and no major investment.

When O’Neill joined Alcoa as CEO, he was the most highly focused and dedicated-to-change person in the organization. He moved around quietly, talking with everyone and getting to know what was really happening. The first thing he introduced us all to, for about a year, was safety, quality, and quality training. That focus altered our outlook about how things should be and also changed our work behavior.

O’Neill’s next move was to turn the entire Alcoa organization upside down. He created what was called the inverted pyramid. The customers were king, at the top of the pyramid. A step down were business leaders, whose job it was to make the customers happy. Functional groups, such as the one to which I belonged, were dismayed because we found ourselves near the bottom of the pyramid. But then O’Neill put the CEO at the very bottom of the pyramid. That was transforming in and of itself, as it caused all of us to change our thinking from focusing on who was at the top of the company to focusing on what function or activity was at the top in terms of importance.

O’Neill followed the introduction of the pyramid with the charge that “[w]e are going to make quantum leap changes to Alcoa’s performance.” He told us to identify best-in-class practices, whether in our business units or functional groups, and he said he wanted all of us to be using such practices within a couple of years. For the finance group, the challenge was clear: we needed to redirect resources while reducing costs. To that end, my group took a close look at the financial closing process, and we undertook it as a significant quality cycle-time reduction project, which is the focus of this paper. We carried out this project successfully at Alcoa, and subsequently were able to help others succeed in similar undertakings

at the U.S. Department of the Treasury and at Martha Jefferson Hospital. The focus of this paper is on Alcoa.

To put this experience in perspective, when we started the project in 1991, Alcoa was a $10 billion company; by 2007, we were a $31 billion company. We had 150 locations in 20 countries when we started; that increased to 316 in 44 countries. Our net income of $0.4 billion in 1991 increased to $2.6 billion in 2007. During this growth, we were also able to achieve significant reductions in systems and processes.

At Alcoa, 70 to 80 percent of our finance people were working on transaction processes. We decided we should reduce the percentage and number of employees working on transaction processes and at the same time give more attention to decision support processes. We initially chose three projects in the controllership function for transforming the company’s finance function. We wanted a common chart of accounts, including setting up a worldwide common accounting and finance language, providing consistent information, and improving communication among business units, among other strategies. We wanted an accelerated closing process, by which we meant we wanted to shorten the closing cycle to three days, significantly improve processes, and provide timely performance information to management. We also wanted to create a shared services center to better pool transaction processing for U.S. businesses, lower costs, improve service, and refocus on business analysis and support. Although people in finance would have liked to focus on shared services, O’Neill preferred accelerated closing, and as CEO he had a weighted vote, so we ended up focusing on that area first.

Our objectives for the three projects were straightforward. We wanted to improve information sharing, achieve better and more timely decision making, institute easier modeling and analysis, improve systems efficiency, ensure that we could adapt more readily to change, enable shared ledger processing, set ourselves up to be ready for growth, and ensure a certain degree of immunity to organizational change. Perhaps the core goal was readiness for growth. Immunity to organizational change was a goal because every time we changed the organization, finance had to expend a great deal of energy shuffling the books around. The accelerated closing project involved the most people and touched on most of the objectives, which made it ideal as the initial focus.

Alcoa’s closing was completed at 4:30 p.m. on the eighth workday of the month. We found that a world benchmark for a comparably structured company was 3 workdays, so we wanted to strive for that. Earlier completion would increase the relevance of the information and free staff time for more value-adding work.

Frankly, our first reaction to the prospect of closing Alcoa’s books in 3 days was skepticism. We thought it was impossible given the global nature

of our enterprise. We had several project guidelines. We wanted to move from a closing time of 8 days to 3 days by February 1993. We set no interim targets, but said we wanted to get to the final goal as quickly as possible, with the quality of data improved. We said we would develop standard metrics that would be published worldwide throughout the company. The last guideline was new for us: publishing metrics on how well we were progressing toward the goal at each location was alien to our culture at the time, but it turned out to have great advantages.

We encountered a great deal initial resistance. People were constantly looking for ways to opt out. They kept asking us to explain the objectives and guidelines. Our response was direct. We simply said, “Here are the guidelines, and you can read them for yourselves.” Then we said, “Just get it done.” Our initial challenge was getting the word out, as many people were involved in the process. Beyond that, we had to overcome innate inertia and move thinking from “why it can’t be done” to “how it will be done.” One key was explaining the real benefits we could expect to reap if we were successful.

Ultimately, we were successful. In just 9 months, 70 percent of the operations had reached their targets. Eight months later Alcoa had matched the world standard with an in-control and capable process. One of the biggest surprises was how quickly we started to make gains in a process we had been doing every month for many years in basically the same way and taking the same amount of time. Our success demonstrates what can be done when staff are empowered and the whole organization is working on a problem.

The results were significant. We saw quality improvement at all locations. We could document productivity improvement in terms of days saved times people in the process. Communication and cooperation were much improved, while frustration with what had been a painful process was greatly reduced. In the change process, we developed advanced-quality tools that were deployed across the entire organization. We were able to get financial information out sooner and to improve performance feedback. We developed a very positive image in the financial community because of our insistence that efficiency matters. One of the most relevant lessons for health care is that we demonstrated that significant improvements can be made to administrative processes relatively quickly and inexpensively, resulting in greater satisfaction among both employees and management. Moreover, we showed the rest of the organization that an administrative process could be improved; later, the CEO used that to his advantage to keep everybody moving toward quantum change. We were then able to focus more resources on developing our new chart of accounts and creating the U.S. shared service center, which provided even more significant cost

reductions and benefits to Alcoa’s finance organization, as indicated in our project objectives.

More recently, we helped apply similar strategies to streamlining the financial closing process at the Department of the Treasury. This was a larger, much more complex organization in some respects, with components ranging from the Internal Revenue Service and the Customs and Border Patrol to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, but the nature of the problem was similar. As of January 2001, the bureaus and various reporting entities were taking 20 workdays to submit monthly financial data to the Treasury’s Financial Analysis and Reporting System. As we had found at Alcoa, however, world-class organizations close their monthly books in 3 days. On April 11, 2001, then-Secretary O’Neill challenged the department to achieve a 3-day close by no later than July 3, 2002. There was significant concern as to whether this was feasible in light of the size and complexity of the U.S. Treasury. However, because this was a directive from the top, with no opt-outs allowed and most of the same project guidelines as at Alcoa, the closing project was started. I am still amazed at how rapidly the number of days to close dropped in the early months of the project, given the complexity of the government. The success underscores the fact that there is a tremendous amount of know-how in an organization. People want respect. They want a challenge. Give them a stretch goal, tell them what to do, and get out of their way. Within every organization, that know-how is in place. We simply fail to call on it or fail to manage it properly with efficiency as a focus.

The benefits of the 3-day close at Treasury were significant. Data have become more timely, accurate, and meaningful. There is better communication with internal and external organizations. There is more time to perform analysis and focus on other goals. The change process brought to light and ultimately reengineered old and inefficient ways of operating. The process forced the department to work more efficiently and put the previous month “to bed” earlier. The change process identified and resolved key system fixes. Staff restructured some of their contracts so as to obtain more timely information from contractors. The process moved a monthly cost meeting one week earlier in the month, and overall it helped with budget execution and monitoring of the status of funds. The process is still in effect today, and I am told that it was a factor in the entire federal government’s achieving a 45-day annual closing that President Bush had challenged them to accomplish. Ultimately, the process is all about adding value.

Finally, we applied a similar process at Martha Jefferson Hospital, a not-for-profit, 176-bed community hospital based in Charlottesville, Virginia. Fully accredited by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, the hospital has a caring tradition of more than 100 years, with close ties to its community. Its key services include a can-

cer care center, a cardiology care center, a digestive care center, a vascular center, a women’s health center, an emergency department, and primary care services. The medical staff includes nearly 400 affiliated physicians representing more than 35 specialties.

The financial people at the hospital embraced an ambitious set of goals. One was a project in fiscal year (FY) 2005 to reduce the financial close process from 15 to 5 business days by FY 2007. Unlike Alcoa or the U.S. Treasury, Martha Jefferson used more detailed guidelines for other process improvements they wanted to accomplish. Specifically, they wanted to enhance the use of systems for automation by effectively utilizing a recently installed general ledger system to implement a new time and attendance system, to implement an operating budget system for automation of budget processes and management reporting, to institute firm monthly close deadlines, and to implement processes throughout the month to ensure data quality at the end of the month.

Among their challenges was the need to break from the usual “That’s the way we’ve always done it” way of thinking. There was also an issue of converting serial steps to a parallel process where appropriate and focusing on doing what one can when one can vs. when one must. Obtaining commitment was another challenge, but it ended up being a success factor since the finance organization put it on the line.

I actually thought the hospital’s project guidelines were a bit more detailed because of the added system implementation work they needed to accomplish, and they did not want to aim for a 3-day close in the initial objective. Although it took a little longer to reach the 5-day closing, they still succeeded and are extremely excited about this accomplishment. Their report on the closing progress showed the same rapid improvement in the early months as was achieved at Alcoa and the U.S. Treasury. I have recently learned that they continue to make progress and are now approaching the 3-day closing.

Key success factors at Martha Jefferson included a commitment to process improvement, deadlines, and each other, as well as to teamwork and a belief in the “possibilities.” The payoffs were significant and came in the form of timeliness, transparency, and ease of access. Staff could now spend more time with information and less with data. The accuracy, reliability, and consistency of financial information were all improved. Paper-based reporting was eliminated. There was earlier and enhanced access to appropriate financial information at each level of the organization, and overall, finance personnel were better able to serve and support operating departments in financial management of the organization.

Many applications of this process could benefit health care, and similar processes could likely be applied throughout the healthcare enterprise with

similar quantum-change benefits. When it comes to the problems or opportunities of health care, I think the glass is half full, not half empty.

VETERANS HEALTH AFFAIRS: TRANSFORMING THE VETERANS HEALTH ADMINISTRATION

The veterans healthcare system administered by the VA was established after World War I to provide medical and rehabilitation care for veterans having health conditions related to their military service. Today it is the nation’s largest healthcare system, although it is an anomaly in American health care insofar as it is centrally administered, fully integrated, and both paid for and operated by the federal government.

As the system grew and became more bureaucratic, its performance deteriorated, and it failed to adapt to changing circumstances. By the early 1990s, VA health care was being widely criticized for providing fragmented and disjointed care of unpredictable and irregular quality that was expensive, difficult to access, and insensitive to individual needs.

Between 1995 and 1999 the VA healthcare system underwent a radical reengineering that addressed management accountability, care coordination, performance measurement, resource allocation, and information management. Numerous systemic changes were implemented, producing dramatically improved quality, service satisfaction, and efficiency. VA health care is now recognized as among the best in America, and the VA transformation is viewed as a model for healthcare reform and organizational transformation.

A Short History of the Veterans Healthcare System

The United States provides the most comprehensive benefits for military veterans of any country in the world. The special status accorded veterans dates back to colonial days (VHA, 1967; Weber and Schmeckebiar, 1934).

Veterans healthcare benefits were originally limited to infirmary care provided by the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) or by contract civilian hospitals. President Lincoln set the precedent for the government’s providing institutional care for veterans when he established the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in 1865.

The sharply increased number of veterans needing medical care after World War I prompted Congress to increase healthcare benefits for veterans, transfer 57 USPHS hospitals to the U.S. Veterans Bureau, and approve

hospital care for indigent veterans without service-connected disabilities (Mather and Abel, 1986; VHA, 1967).

In 1930 President Hoover merged the Bureau of Pensions, the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, and U.S. Veterans Bureau to establish the Veterans Administration (Mather and Abel, 1986; Weber and Schmeckebiar, 1934).2 This new independent federal agency was charged with consolidating and coordinating the various veterans benefit programs that existed for the nation’s then 4.7 million veterans. The founding of the veterans healthcare system is generally linked with the establishment of the VA (Piccard, 2005; Weber and Schmeckebiar, 1934)3 at a time when there was essentially no public or private health insurance in the United States.

The veteran population increased suddenly and massively after June 1945. Many of the more than 12 million new veterans produced by World War II sought care from the VA. The agency was overwhelmed. Legislation was enacted in 1946 to establish a new VA Department of Medicine and Surgery to “streamline and modernize the practice of medicine for veterans”4 (Mather and Abel, 1986; VHA, 1967).

To improve the quality and quantity of its medical staff as quickly as possible, the VA sought affiliations with university medical schools (VHA, 1946). Northwestern University and Chicago’s Hines VA Hospital were the first to affiliate. This relationship was widely replicated, establishing a highly successful ongoing partnership between the VA and academic medicine.

The veterans healthcare system grew rapidly during the late 1940s and 1950s, adding more than 70 new hospitals, establishing academic affiliations and teaching programs, expanding research activities, and putting into place new venues of care (Mather and Abel, 1986; VHA, 1967). During these years the VA emphasized hospital inpatient and medical specialist care, consistent with what was then viewed as the best medical care.

As the system grew and became more complex, it became increasingly cumbersome and bureaucratic as well as increasingly underfunded and understaffed. During the 1970s and 1980s, a number of embarrassing quality-of-care incidents occurred at individual VA hospitals. Widespread media coverage of these incidents indicted the whole system. Many Vietnam veterans, already angry about what they perceived to be an unjust and unending war, as well as the public’s often hostile response to them when they returned home, were alienated by the system’s seemingly lackluster response

![]()

2 Executive Order 5398, July 21, 1930.

3 Although the founding of the veterans healthcare system is generally linked with formation of the VA, the system actually took form incrementally over several decades in the first half of the 20th century. Some authors cite its founding as occurring in 1946, when VA health care was restructured in the aftermath of World War II.

4 See Public Law 79-293 (1946).

to their problems, prompting some disgruntled veterans to stage events to embarrass the VA (Klein, 1981; Longman, 2007).

Responding to the many veterans service organizations that had long sought higher status for veterans programs, President Reagan established the Cabinet-level Department of Veterans Affairs in 19895 (Light, 1992). The Department of Medicine and Surgery was renamed the Veterans Health Services and Research Administration, which was later renamed again to the VHA.6

By 1994 the VA had grown to be the country’s largest healthcare provider, with an annual medical care budget of $16.3 billion, 210,000 full-time employees, 172 acute-care hospitals having 1.1 million annual admissions, 131 skilled nursing facilities housing some 72,000 elderly or severely disabled adults, 39 domiciliaries (residential care facilities) that each year cared for 26,000 persons, 350 outpatient clinics having 24 million annual patient visits, and 206 counseling facilities providing treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The VHA also partnered with most states to fund state-managed skilled nursing facilities for elderly veterans, administered a contract and fee-basis care program paying for “out-of-network” services, and managed a number of nonhealthcare concerns.7

By this time the veterans healthcare system was highly dysfunctional. The quality of care was irregular (Associated Press, 1990; Childs, 1970; GAO, 1987, 1995; Office of the Inspector General and Department of Veterans Affairs, 1990, 1991; U.S. Congress, 1987); services were fragmented, disjointed, and insensitive to individual needs (GAO, 1994a; Light, 1992; Longman, 2007); inpatient care was overused (Booth et al., 1991; GAO, 1989; Smith et al., 1996); customer service was poor (GAO, 1994a; Longman, 2007); and care was often difficult to access, with patients sometimes traveling hundreds of miles or waiting months for routine appointments (GAO, 1993; Longman, 2007). Reflecting popular sentiment, movies

![]()

5 Because of its broad public recognition, “VA” was maintained as the acronym for the new Cabinet Department, albeit now standing for “Veterans Affairs.” The VA became the 14th Cabinet agency in the executive branch of the federal government per Executive Order 5398, 1989.

6 Like the Department of Health and Human Services, which administers its programs through 11 sub-Cabinet agencies (e.g., the Food and Drug Administration, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), the VA administers its many health and social support programs through a number of sub-Cabinet agencies per Public Law 79-293, 1946 (e.g., the VHA, Veterans Benefits Administration, National Cemetery Administration, Board of Veterans Appeals).

7 These nonhealthcare concerns included 32 golf courses, 29 fire departments, a national retail store system (the Veterans Canteen Service), 75 laundries, and 1,740 historic buildings, among other things. The VHA was and continues to be the largest laundry service in the world, and it oversees more historic sites than any entity except the Department of the Interior.

such as Article 99 and Born on the Fourth of July portrayed VA health care as a bleak backwater of incompetence, indifference, and inefficiency.

Between 1995 and 1999, the veterans healthcare system underwent a radical reengineering that markedly improved its quality of care, service satisfaction, and efficiency. In recent years, the VA has been hailed as providing some of the best health care in the United States (Arnst, 2006; CBS Evening News, 2006; Freedberg, 2006; Gearon, 2005; Glendinning, 2007; Krugman, 2008; Rundle, 2001; Stein, 2006; Stires, 2006; Waller, 2006). The veterans healthcare system is now viewed as a model of high-quality, low-cost (i.e., high-value) health care, and a number of authors have advocated it as a model for American healthcare reform (Gaul, 2005; Haugh, 2003; NBC Nightly News, 2006; Oxford Analytica, 2007; Piccard, 2005).

Missions of the Modern Veterans Healthcare System

The VHA is a highly complex organization. Understanding its multiple missions, four of which are specified in statute, is important to understanding the changes in its strategies and tactics.

The VHA’s primary mission is to provide medical care for eligible veterans in order to improve their health and functionality and reduce the burden of disability from conditions related to their military service. Initially, all honorably discharged veterans were eligible for VA health care, but as the system’s cost grew, Congress limited eligibility for VA health care to those who were poor or had a service-connected condition,8 underscoring the safety net role established for the system in 1924 (Steiner, 1971; VHA, 1967; Wilson and Kizer, 1997). This explains in large part why the VA’s patient population is disproportionately older, sicker, and more socioeconomically disadvantaged than the general population or than Medicare beneficiaries (Frayne et al., 2006; Kazis et al., 1999; Rogers et al., 2004; Singh et al., 2005; Yu et al., 2003). Within the VHA’s patient population, a number of groups have been identified as “special populations” because their health conditions are disproportionately prevalent among veterans or particularly related to military service. These special populations include persons with spinal cord injuries, amputations, traumatic brain injury, serious mental illness, substance abuse disorders, PTSD, or blindness; former prisoners of war; Persian Gulf War veterans; and homeless persons. The VHA has a binding obligation to serve these groups and has developed special expertise in treating them.

The VHA’s second mission is to train healthcare personnel (Stevens et

![]()

8 Unlike Medicare or Medicaid, which are entitlement programs that must be funded in accordance with the growth in the number of beneficiaries, veterans health care is a discretionary program that may be funded at whatever level Congress chooses.

al., 1998, 2001). Although most often associated with postgraduate medical education9 (Longman, 2007), the VHA offers training for more than 40 types of healthcare professionals through affiliations with more than 1,100 universities and colleges. More than 100,000 trainees rotate through VHA facilities each year.

The VHA’s third mission is to conduct research that will improve the care of veterans (Rutherford et al., 1999). The VHA conducts research in the basic biomedical sciences, rehabilitation, health services delivery, and quality improvement. Placing a dedicated research program within such an immense healthcare delivery system—and one with a stable patient population that has a high prevalence of chronic conditions—creates an especially fertile environment for research.

The system’s fourth mission is to provide contingency support to the military healthcare system and the Department of Homeland Security. In times of national emergency, the VHA provides personnel, pharmaceuticals, supplies, and other support to the National Disaster Medical System (Kizer et al., 2000a; U.S. Congress, 2001).

The final mission of the VHA is to serve the homeless because about a third of adult homeless men in the United States are veterans. The VA is the nation’s largest direct provider of services to homeless persons, providing healthcare services (and other services) to more than 65,000 homeless veterans each year (Rosenheck and Kizer, 1998).

Transforming the Veterans Healthcare System

In 1994 there was widespread consensus that the veterans healthcare system needed a major overhaul, but there was little agreement about how to effect the needed change. Under new leadership drawn from outside the system, a radical reengineering of VA health care was proposed (Kizer, 1996; Kizer and Garthwaite, 1997). The reengineering was intended to create a seamless continuum of consistent and predictable high-quality, patient-centered care that was of superior value.

The concept of value was a fundamental underpinning of the reengineering. In particular, the reengineering sought to create an organization with the following features: (1) superior quality of care that was predictable and consistent throughout the system, (2) health care that was of equal or better value than care provided by the private sector, and (3) high reliability.

![]()

9 Approximately half of all American medical students and one-third of all postgraduate physician residents receive training at VA facilities each year. Two-thirds of U.S.-trained physicians have received at least some of their training at a VA medical center. About 85 percent of VA hospitals are university-affiliated teaching hospitals (i.e., 130 of 153 hospitals in 2007), and 70 percent of the VA’s 14,000 staff physicians have university faculty appointments.

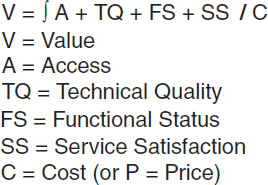

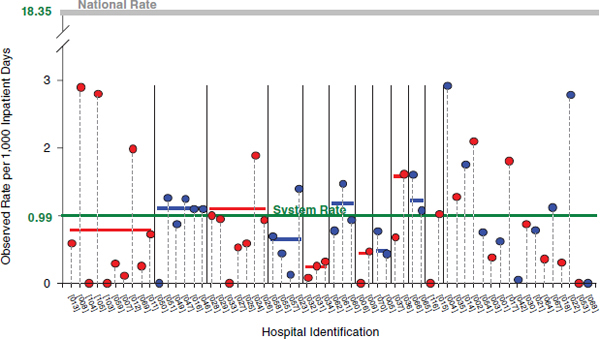

FIGURE 4-1 The Veterans Health Administration value equation. Value is defined operationally as being a function of access, technical quality, patient functionality, and service satisfaction, all divided by cost or price.

It was argued that if the VHA were to continue to enjoy public support, it would have to be able to demonstrate its value to both veterans and the public. To operationalize the concept of value, a relatively objective method for determining value was needed. This method was accomplished by use of the value equation shown in Figure 4-1, in which value is deemed to be a function of technical quality, access to care, patient functional status, and service satisfaction, all divided by the cost or price of the care. Each of the four value domains in the numerator was linked to a menu of standardized performance measures10 (Light, 1992).

The reengineering was based on five interrelated and mutually reinforcing strategies: (1) create an accountable management structure and management control system, (2) integrate and coordinate services across the continuum of care, (3) measure performance and create an environment supportive of improvement and high performance, (4) align the system’s finances with desired outcomes, and (5) modernize information management.

Change Strategy 1: Create an Accountable Management Structure and Management Control System

The most visible steps taken to increase management accountability were (1) the establishment of a new operational structure based on the concept of integrated delivery networks, (2) the implementation of a new performance management system, and (3) decentralization of much of the operational decision making. It was envisioned that these and other

![]()

10 To facilitate valid comparison with the private sector, whenever possible the performance measures are the same as those used by the private sector.

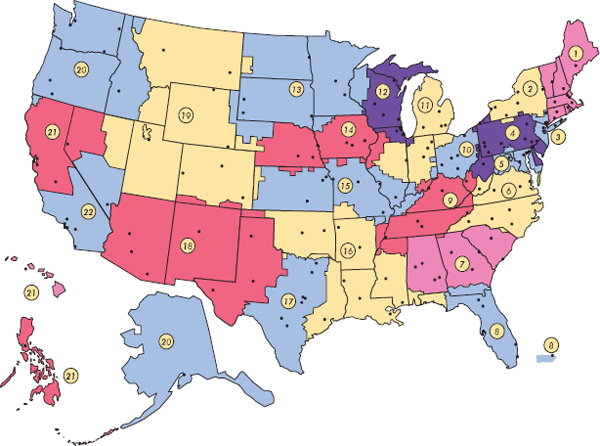

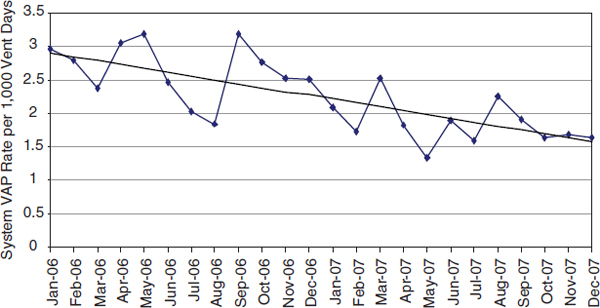

FIGURE 4-2 Map of the Veterans Health Administration’s 21 Veterans Integrated Service Networks.

SOURCE: VA, 2010.

measures would provide a foundation for the emergence of a new organizational culture in which accountability would be a core value.

Establishment of Veterans Integrated Service Networks After development, vetting, and requisite congressional approval of the restructuring plan, in fall 1995 the VHA’s more than 1,100 sites of care delivery were organized into 22 Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs, pronounced “visions”) (Kizer and Garthwaite, 1997; Kizer and Pane, 1997). The decision to have 22 VISNs was based on a judgment about how care could best be distributed, and the catchment areas of the VISNs were determined according to prevailing patient referral patterns, the ability of each VISN to provide a continuum of primary to tertiary care with VA assets, and relevant state or county jurisdictional boundaries11 (U.S. Congress, 1987). The number of VISNs was reduced to its current 21 in 2002 (Figure 4-2).

![]()

11 A typical VISN encompassed 7 to 10 VA medical centers, 25 to 30 ambulatory care clinics, 4 to 7 nursing homes, 1 to 2 domiciliaries, and 10 to 15 counseling centers. The population served by each VISN averaged 150,000 to 200,000.

The VISN became the system’s basic operating unit. It provided a structural template for coordinating services, pooling resources to meet the needs of the served population, and ensuring continuity of care; reducing service duplication and administrative redundancies when appropriate; improving the consistency and predictability of services; promoting more effective and accountable management; and, overall, optimizing healthcare value (Kizer and Garthwaite, 1997).

Implementation of a new performance management system A new performance management system was instituted in 1995 (Kizer, 1996; Trevelyan, 2002). Two key elements of this new system were the measurement of performance using standardized metrics and an annual performance contract that was used to clarify management expectations, encourage managers’ engagement, and hold management accountable for achieving specified results. The use of such performance contracts was novel within the federal government. In this new performance management system, the organization’s missions were aligned with quantifiable strategic goals, progress toward these goals was tracked using performance measures, the performance data were made widely available, and management was held accountable for the results achieved.

Concomitant with efforts to improve the quality of care, steps were taken to increase the knowledge base concerning clinical quality improvement and to encourage innovation. These efforts included initiation of the VA National Quality Scholars Fellowship Program (Batalden et al., 2002) and the VA Faculty Fellows Program for Improved Care for Patients at the End of Life (Block, 2002; Gibson, 1998), implementation of the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) (Ashton et al., 2000; Bozzette et al., 2000; Demakis et al., 2000; Every et al., 2000; Feussner et al., 2000; Finney et al., 2000; Fischer et al., 2000; Hynes et al., 2004; Kizer et al., 2000b; Krein et al., 2000), and hundreds of innovations in care delivery (Beason, 2000; Charles, 2000; Kizer, 2000; VHA, 1996a).

Decentralization of operational decision making In an effort to help change the organizational culture, a substantial amount of the operational decision making that had formerly been done in headquarters was delegated to the VISNs. The goal was to decentralize decision making to the lowest, most appropriate management level. Although quality improvement targets were often determined centrally, operational strategy and tactics to achieve the goals were left up to the VISNs.

Change Strategy 2: Integrate and Coordinate Services

In 1994 the two biggest problems with the VA’s delivery of care were its variable quality and its fragmentation. Fragmentation of care is a serious problem everywhere in American health care, but it was especially serious in the VA because of the system’s historical bias toward providing specialist-based, inpatient care; the limited use of care management and primary care; the sociodemographics of the VA’s service population; the anachronistic laws governing eligibility for care; and the high rate of “dual-eligible” patients12 (GAO, 1994b, 1995; Tseng et al., 2004).

The VHA transformation sought to reduce care fragmentation through a number of systemic changes aimed at coordinating and integrating service delivery across the continuum of care. Particularly important were the implementation of universal primary care, revision of the laws governing eligibility for care, and creation of the VISN management structure. Unsuccessful attempts were made to gain legislative authority for VA medical centers to participate in the Medicare program to help rationalize the care of dual eligibles.

Implementation of primary care A number of primary care pilot projects had been initiated at VA medical centers in the late 1980s and early 1990s (Cope et al., 1996; Rubenstein et al., 1996a, 1996b), but only about 10 percent of VA patients were enrolled in primary care at the end of FY 1994. Universal primary care was viewed as a lynchpin for integrating and coordinating care delivery and was believed to be essential regardless of what else was done to restructure the system. Thus a primary care initiative was launched in early FY 1995 before the VISN reorganization and other reengineering plans had been finalized (Management Decision and Research Center, 1995; Yano et al., 2007).

Eligibility reform The federal laws governing eligibility for VA health care were a major cause of service delivery fragmentation. These laws often required that patients be hospitalized for procedures routinely done on an outpatient basis elsewhere. They also required that the VHA treat only a veteran’s service-connected condition. Such service-related conditions were often not the veteran’s greatest health care need and were sometimes being exacerbated by non-service-related conditions that the VA could not legally treat. Thus one of the keys to transforming VA health care was to change the eligibility laws so that patients could receive whatever care was needed and be treated in the most appropriate medical care setting.

![]()

12 “Dual-eligible” patients are eligible for care provided by the VA and another system. Most often this is Medicare, but it also may be the Indian Health Service, Tri-Care offered by the Department of Defense, or private indemnity insurance.

Repeated attempts to change these laws over the previous decade had been unsuccessful because key congressional leaders feared the change would increase use and, consequently, costs. However, VHA leadership convincingly argued that the eligibility laws made it impossible to manage the cost of the system prudently. This argument was pivotal to gaining enactment of the Veterans Health Care Eligibility Reform Act of 1996 (Public Law 104-262, 1996). This law gave the VHA the authority needed to provide care in any medically appropriate setting, to outsource services and partner with non-VA healthcare providers, and to establish an enrollment system.

Other efforts to increase the coordination and integration of care Other steps were taken to better coordinate and integrate care. For example, between 1995 and 1999, 52 VA medical centers were merged into 25 multicampus facilities, each under single management; multi-institutional “service lines” (e.g., lines in primary care or behavioral health) were implemented in some VISNs; multidisciplinary “Strategic Healthcare Groups” were organized at VHA headquarters (Kizer, 1996); care management was implemented as a system-wide strategic initiative (Employee Education System, 1999); better continuity of care through more convenient access was pursued through the establishment of hundreds of new community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs); and a National Formulary of prescription drugs, nonprescription products, and medical supplies was established to promote evidence-based drug prescribing and improved pharmaceutical management (IOM, 2000a; Kizer et al., 1997; Sales et al., 2005; Young, 2007).

Change Strategy 3: Measure Performance

Performance measurement and the public reporting of performance were considered critical to improving the quality of care, standardizing superior quality, and demonstrating improved performance. As part of the performance management system, clinical performance was routinely measured and tracked. Two specific instruments were developed to carry out the performance assessments: the Prevention Index and the Chronic Disease Care Index13 (Kizer, 1999). Both were instituted in late FY 1995 to track

![]()

13 The Prevention Index consists of nine clinical interventions that measure how well VHA practitioners follow nationally recognized primary prevention and early detection recommendations for eight conditions with major social consequences: influenza and pneumococcal diseases, tobacco consumption, alcohol abuse, and cancer of the breast, cervix, colon, and prostate. The Chronic Disease Care Index consists of 14 clinical interventions that assess how well practitioners follow nationally recognized guidelines for 5 high-volume diagnoses: ischemic heart disease, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, diabetes mellitus, and obesity.

adherence to established clinical best practices for common preventable or chronic conditions. A Palliative Care Index was instituted in 1997 to track adherence to best practices for end-of-life care (Penrod et al., 2007; Quill, 2002).

Another important clinical quality improvement effort was the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP), begun in 1991 in response to a 1986 congressional mandate that the VA compare its risk-adjusted surgical results with those of the private sector (Best et al., 2002; Daley et al., 1997; Khuri, 2006; Khuri et al., 1995, 1998). The intent and methods of the NSQIP, which were already in place, essentially mirrored the reengineering strategies, and NSQIP was embraced as part of the transformation effort.

Other quality improvement initiatives were launched to address specific clinical conditions or operational issues, including pain management (Cleeland et al., 2003; Schuster, 1999), end-of-life care (Block, 2002; Gibson, 1998; Penrod et al., 2007; Quill, 2002), cancer (Wilson and Kizer, 1998), HIV/AIDS (Bozzette et al., 2000; Korthuis et al., 2004), pressure ulcers (Berlowitz and Halpern, 1997; Berlowitz et al., 1999, 2001), acute myocardial infarction (Landrum et al., 2004; Petersen et al., 2000, 2001, 2003; Popescu et al., 2007; Fihn et al., 2009), and hepatitis C (Holohan et al., 1999; Mitchell et al., 1999; Roselle et al., 2002; Wright et al., 2000). The use of evidence-based clinical guidelines was strongly encouraged (Kizer, 1998; Management Decision and Research Center, 1998; VHA, 1996b). The VHA partnered with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement on “breakthrough collaboratives” for reducing waiting times, improving operating room performance, and improving access to primary care, among other things (Carver, 2002; Kizer, 1998; Management Decision and Research Center, 1998; Mills and Weeks, 2004; Mills et al., 2003; Roselle et al., 2002). Clinical Programs of Excellence were established,14 and a knowledge management tool modeled after the U.S. Army’s Lessons Learned Center, known as the VA Lessons Learned Project, was created along with an intranet-based Virtual Learning Center (VLC) to promote rapid-cycle learning from actual successes and errors that had occurred in the system (Wahby et al., 2000). By the end of 2000, the VLC had 730 learning cases. In this same vein, a high-performance employee development model was also instituted (American Health Consultants Inc., 2002; VHA, 1996c).

The VHA took a leadership role in the emerging national patient safety movement and worked closely with other national organizations on patient safety issues (Davis, 1998; Leape et al., 1998; Luciano, 2000; NYT, 1999; Shapiro, 1999; Stalhandske et al., 2002). It launched its pioneering

![]()

14 Under Secretary of Health’s Information Letter, Designating Clinical Programs of Excellence, February 10, 1997.

patient safety initiative in 1997. This five-pronged initiative was intended to build an organizational infrastructure to support patient safety (e.g., establishing the VA National Center for Patient Safety in 1998), to create an organizational culture of safety, to implement safe practices, to produce new knowledge about patient safety through research, and to partner with other organizations to promote more rapid problem solving for patient safety issues.

Change Strategy 4: Align System Finances with Desired Outcomes

Another systemic problem with veterans health care in 1995 was that the Resource Planning and Management Resource Allocation Methodology used to distribute congressionally appropriated funds to the medical centers was neither predictable nor easily understandable, and it perpetuated inefficiencies. Thus another central reengineering strategy was to align funding with operational efficiency and clinical quality improvement.

Creation of the Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation methodology To allocate funds in a predictable, fair, and easy-to-understand manner, a new global, fee-based resource allocation system known as VERA—the Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation methodology—was developed (The Lewin Group and PricewaterhouseCoopers, 1998; VHA, 1997a, 1997b, 1998; Wasserman et al., 2001, 2003). This methodology took into account the veteran population shifts that had occurred in the 1970s and 1980s (e.g., migration from the Rust Belt to the Sun Belt), as well as the high degree of morbidity prevalent in the veteran population.15