8

Approaches to Achieving Recommended Gestational Weight Gain

To understand the challenges that may arise in implementing the proposed guidelines on gestational weight gain (GWG) presented in Chapter 7, the committee reviewed the present environment for childbearing (see Chapter 2 for details) as well as interventions that have been conducted to improve GWG in response to the Institute of Medicine (IOM) 1990 guidelines. In addition, the committee considered the guidance that these interventions might provide for implementation of these revised guidelines. Although proposing a complete implementation and evaluation plan is beyond the scope of the committee’s work, this chapter provides a framework for developing such a plan.

CURRENT CONTEXT FOR CHILDBEARING AND GESTATIONAL WEIGHT GAIN

As discussed in Chapter 2, women who are having children today are substantially heavier than at any time in the past. Moreover, at least half of all pregnancies are unwanted or mistimed (IOM, 1995). These facts highlight the difficulties that women face in achieving one of our primary recommendations, namely that women should conceive at a weight within the normal range of body mass index (BMI) values. It is beyond the committee’s scope of work to consider how to achieve this objective. Nonetheless, it is important for women to do so and for the government as well as private voluntary organizations to assist them.

The same factors that have caused women of childbearing age to be

heavier than in the past challenge them to meet the previous guidelines (IOM, 1990) and will continue to make it difficult for women to meet the new guidelines for GWG. For example, as discussed in Chapter 2, one trend of concern is the increase in consumption of foods with low nutrient density; this has special implications for pregnancy and lactation, which require modest increases in energy but greater increases in vitamin and mineral intake. Also as discussed in Chapter 2, national data indicate that a high proportion of women of childbearing age fail to meet current guidelines for physical activity. Improvement in both of these statistics could contribute toward helping women enter pregnancy at a healthy weight as well as to meet the proposed guidelines for GWG.

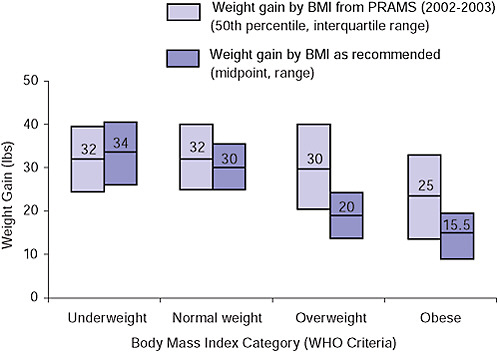

These new guidelines should also be considered in the context of data on women’s reported GWG, which the committee assembled from a series of studies with relatively large samples of women (Table 8-1). As shown in Table 8-1, the mean gains of underweight women are within the new guidelines. This is less often the case for normal weight women, where the mean gain in some samples is at or above the upper limit of the new guidelines. This indicates that a substantial proportion of normal weight women would exceed desired GWG ranges according to the new guidelines. The mean GWG values for overweight and obese women exceed the upper end of the new guidelines by several kilograms. Even when this analysis is restricted to the most recent (2002-2003) multi-state data from Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), the same conclusions hold (Figure 8-1). These data provide a strong reason to assume that interventions will be needed to assist women, particularly those who are overweight or obese at the time of conception, in meeting the new GWG guidelines.

The review of interventions that have been conducted based on Nutrition During Pregnancy (IOM, 1990) (see below) provide a preview of the challenges that will be faced in implementing the new guidelines in this report. Although the committee recognizes that developing graphical representations to assist caregivers and their clients in conveying the importance of appropriate weight gain during pregnancy is important, the type of expertise represented on the committee as well as the commitment of time and resources limited the extent to which it could develop such material into a format that could be readily disseminated.

Although data from observational studies have been consistent in showing an association between gaining within the IOM (1990) guidelines and having a lower risk of adverse outcomes (Carmichael et al., 1997; Abrams et al., 2000; Langford et al., 2008; Olson, 2008), this does not mean that women who gain outside the guidelines will have a bad outcome (Parker and Abrams, 1992). This is because many factors other than GWG are related to the short- and long-term outcomes of pregnancy. Nonetheless, monitoring GWG is useful for identifying women who might benefit from

TABLE 8-1 Gestational Weight Gain (kg) by Prepregnant BMI Categories Among Large Studies Compare to New Guidelines

|

Prepregnant BMI Category |

New GWG Guidelines |

Study |

||||

|

Sweden, National (1994-2002)a |

Danish National Birth Cohort (1996-2002)b |

Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (2002-03)c |

New York City Vital Statistics Birth Data (1995 to 2003)d |

Pregnancy, Infection, and Nutrition Cohort Study (2001-2005)e |

||

|

Underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2) |

12.5-18.0 |

13.5 ± 0.03 (SEM) (n = 72,361) |

15.3 ± 5.1 (SD) (n = 2,648) |

14.8 ± 0.27 (SEM) (n = 1,628) |

15.1 ± 5.01 (SD) (n = 1,632) |

15.4 ± 4.4 (SD) (n = 176) |

|

Normal weight (18.5-24.9 kg/m2) |

11.5-16.0 |

13.8 ± 0.01 (SEM) (n = 368,063) |

15.8 ± 5.2 (SD) (n = 41,569) |

15.0 ± 0.10 (SEM) (n = 11,513) |

15.1 ± 5.25 (SD) (n = 19,892) |

16.6 ± 5.3 (SD) (n = 652) |

|

Overweight (25.0-29.9 kg/m2) |

7.0-11.5 |

13.2 ± 0.02 (SEM) (n = 153,769) |

14.7 ± 6.4 (SD) (n = 11,861) |

13.9 ± 0.16 (SEM) (n = 5,027) |

14.1 ± 6.07 (SD) (n = 7,893) |

15.5 ± 6.2 (SD) (n = 126) |

|

Obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) |

5.0-9.0 |

— |

10.5 ± 8.3 (SD) (n = 4,890) |

11.2 ± 0.20 (SEM) (n = 4,588) |

11.9 ± 6.84 (SD) (n = 4,890) |

12.0 ± 7.1 (SD) (n = 277) |

|

Obese, class I (30-35 kg/m2) |

Not specified |

11.1 ± 0.05 (SEM) (n = 43,128) |

11.4 ± 7.5 (SD) (n = 3,541) |

— |

12.7 ± 6.53 (SD) (n = 3,077) |

— |

|

Obese, class II (35-40 kg/m2) |

Not specified |

8.7 ± 0.11 (SEM) (n = 14,713) |

7.7 ± 9.4 (SD) (n = 1,273) |

— |

11.1 ± 7.17 (SD) (n = 1,166) |

— |

|

Obese, class III (≥ 40 kg/m2) |

Not specified |

— |

— |

— |

9.5 ± 7.00 (SD) (n = 647) |

— |

|

aCedergren, 2006 (BMI categories: underweight = < 20 kg/m2; normal weight = 20-24.9 kg/m2; obese, Class II = ≥ 35 kg/m2). bInformation contributed to the committee in consultation with Nohr (see Appendix G, Part I); Obese, Class II and III are combined. cP. Dietz, CDC, personal communication January 2009 (states included: AK, AL, FL, ME, NY [excludes NYC], OK, SC, WA, WV). dInformation contributed to the committee in consultation with Stein (see Appendix G, Part III). eDeierlein et al., 2008 (BMI categories: underweight = < 19.8 kg/m2; normal weight = 19.8-26.0 kg/m2; overweight = 26.0-29.0 kg/m2; obese = > 29.0 kg/m2). |

||||||

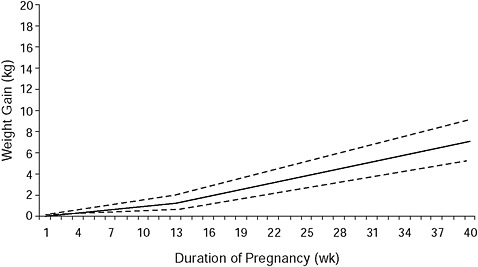

FIGURE 8-1 Comparison of weight gain by BMI category between data reported in the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2002-2003, and weight gain as recommended in the new guidelines.

intervention (Parker and Abrams, 1992), and some interventions have been beneficial (see below).

REVIEW OF INTERVENTION STRATEGIES

The IOM (1990) report made specific suggestions to improve the utility and success of its guidelines. These included providing guidance on measurement of GWG as well as on counseling of pregnant women. In particular, it was recommended that women and their care providers “set a weight gain goal together” early in pregnancy and that women’s progress toward that goal be monitored regularly. Two additional publications from the IOM Committee on Nutritional Status During Pregnancy and Lactation provided further guidance on how to achieve the weight-gain guidelines. First, Nutrition Services in Perinatal Care (IOM, 1992b) called for integrating “basic, patient-centered, individualized nutrition care” into the medical care of every woman beginning before conception and continuing until the end of the breastfeeding period. Second, Nutrition During Pregnancy and

Lactation: An Implementation Guide (IOM, 1992a) called for a dietary assessment of pregnant women early in gestation with a referral to a dietitian if needed. Although such services are not uniformly available today and may not be covered by medical insurance plans, the committee endorses these recommendations as they have only become more important as childbearing women have become heavier. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recently made similar recommendations for nutrition counseling specifically for obese women (ACOG, 2005).

Only limited information is available to determine what advice women have actually received about GWG since the publication of the IOM (1990) guidelines. As described in detail in Chapter 4, only two studies have evaluated the type of GWG advice being given and how it compares to the IOM (1990) recommendations. Cogswell et al. (1999) and Stotland et al. (2005) reported that a high proportion of women were either given no advice on how much weight to gain during pregnancy or were advised to gain outside of the recommended range for their prepregnant BMI value. Both groups of investigators called for greater effort to educate health care providers about the IOM (1990) guidelines. In another study that considered the issue from the physician’s perspective, Power et al. (2006) reported that the majority of the 900 obstetrician-gynecologists who responded to a mailed questionnaire used BMI to screen for obesity and counseled their patients about weight control, diet, and physical activity. Taken together, these studies suggest that there is a discrepancy between what physicians say they are doing and what women say they are receiving. As a result, there is room for improvement in the process of advising women about GWG.

Status of Interventions to Meet the IOM (1990) Guidelines

The IOM (1990) report called for testing the recommended ranges of GWG not just against the effectiveness of specific interventions employed to improve weight gain but also against outcomes. To date, however, only a limited number of investigators have tested interventions intended to help women gain within the guidelines (reviewed in Olson, 2008). Few studies have examined guidance on helping women gain more weight during pregnancy. In their review, Kramer and Kakuma (2003) found that advice to increase energy and protein intake was successful in achieving the goals of increased energy and protein intake but not in increasing GWG. Balanced energy and protein intake were associated with very small (21 g/week) increases in GWG; high-protein supplements were not associated with any increase in GWG. Kramer and Kakuma (2003) also reviewed studies of energy/protein restriction in overweight women or those with high GWG and found that this approach was associated with reduced weekly weight gain.

Most recent studies have focused on various ways to help women to limit their weight gain during pregnancy. None of four trials conducted in North American populations was completely successful in helping women limit GWG and adhere to the IOM (1990) guidelines. First, in a study of Cree women from Quebec, Gray-Donald et al. (2000) used a pre-post design and included 107 women in the control and 112 women in the intervention groups. All of the subjects were obese before conception and at high risk of developing gestational diabetes mellitus. Women in the intervention group were “offered regular, individual diet counseling, physical activity sessions and other activities related to nutrition,” but the intervention had only a “minor impact” on the subjects’ diets and no effect on GWG, plasma glucose concentration, birth weight, the rate of cesarean delivery or postpartum weight.

Second, Olson and coworkers (2004) also used a pre-post design in their study of normal- and overweight white women from a rural community in New York. The intervention included monitoring of weight gain by health care providers and patient education by mail. Overall, there was no difference between the control (n = 381) and intervention (n = 179) groups in GWG or postpartum weight retention at 1 year. Among the low-income women in the sample, however, those in the intervention group gained less than those in the control group. Third, Polley et al. (2002) randomized 120 normal or overweight women recruited from a hospital clinic serving low-income women into either a stepped-care behavioral intervention or usual care. The stepped-care behavioral intervention was successful in reducing the proportion of normal weight but not overweight women who exceeded the IOM (1990) guidelines for GWG. It did not, however, affect weight retention measured at 8 weeks postpartum. Finally, Asbee et al. (2009) randomized women to receive either an organized, consistent program of intensive dietary and lifestyle counseling or routine prenatal care. Among the 100 women who completed the trial, those randomized to the intervention group gained less weight during pregnancy (29 pounds) than those randomized to routine care (36 pounds) but were not more successful in adhering to the recommended guidelines.

In contrast, two of three interventions tested in Scandinavian populations were successful in reducing GWG. In Sweden, Claesson et al. (2008) offered 160 pregnant women additional visits with a midwife that were designed to motivate them to change their behavior and obtain information relevant to their needs. Those who attended the program were also invited to an aqua aerobic class once or twice a week that was specially designed for obese women. The 208 obese pregnant women in the control group received usual care. Compared to the control group, women in the intervention group gained 2.6 kg less weight during pregnancy and 2.8 kg less between early pregnancy and the postnatal check-up. There were no

differences between the groups in type of delivery or infant weight at birth. In Denmark, Wolff et al. (2008) randomized 50 obese pregnant women to receive 10 1-hour dietary consultations that were designed to help them restrict their GWG to 6-7 kg or usual care. The women in the intervention group were successful in limiting both their energy intake and their gestational weight gain compared to those in the control group. The exception was the pilot study in Finland by Kinnunen et al. (2007), in which primiparous pregnant women were recruited from six public health clinics. Most of these women had a normal prepregnant BMI. The 49 women in the intervention group received 5 individual counseling sessions on diet and leisure-time physical activity; the 56 controls received usual care. Although the intervention improved various aspects of the subjects’ diets, it did not prevent excessive GWG.

The studies in Sweden (Claesson et al., 2008) and Denmark (Wolff et al., 2008) demonstrate that it is possible to motivate obese pregnant women to limit their weight gain during pregnancy to 6-7 kg. Achieving this goal required a substantial investment in individual dietary or motivational counseling and, in Sweden, also the provision of specially designed aqua aerobics classes. The individualized attention that characterized these successful interventions would be expensive to duplicate on a wide scale. However, the significant improvement in serum insulin concentrations seen in the study of obese Danish women by Wolff et al. (2008) might provide adequate justification for this expenditure.

Some measure of individualized attention was provided in all of the other studies as well, but they were not successful. None of the three studies with normal weight and/or overweight women enrolled was uniformly successful (Polley et al., 2002; Olson et al., 2004; Kinnunen et al., 2007). Only two of the three studies with obese women enrolled were successful (i.e., Gray-Donald et al., 2000 was unsuccessful; Claesson et al., 2008, and Wolff et al., 2008, were successful).

It is noteworthy that none of these trials had sufficient statistical power to establish that those whose weight gain stayed within the IOM guidelines or reached the investigators’ target had better obstetric outcomes than those who did not. In contrast, there is evidence that these interventions helped some of the subjects reduce postpartum weight retention (Olson et al., 2004; Kinnunen et al., 2007; Claesson et al., 2008).

For the first time, these new guidelines provide a specific weight-gain range for obese women. This specificity should assist researchers in developing targeted interventions to determine how best to help women to gain within this range as well as to evaluate whether those who do gain appropriately have better short- and long-term outcomes for themselves and their infants than those who do not.

IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGIES FOR NEW GUIDELINES

The committee worked from the perspective that the reproductive cycle begins before conception and continues through the first year postpartum. Opportunities to influence maternal weight status are available through the entire cycle. Although it is beyond the scope of this report to consider the evidence associated with timing, duration, or strength of specific strategies or interventions, here the committee offers a basic framework for possible approaches to the implementation guidelines, with a particular focus on consumer education and strategies to assist practitioners and public health programs. A basic goal of this framework is to help women improve the quality of their dietary intake and increase their physical activity to be able to meet these new guidelines. These behavioral changes will need to be supported by both individualized care and community-level actions to alter the physical and social environments that influence dietary behaviors. A comprehensive review of the evidence associated with such actions and guidelines for their use will require future analyses, as was done in the report Nutrition During Pregnancy and Lactation: An Implementation Guide (IOM, 1992a).

To meet the recommendations of this report fully, two different challenges must be met. First, a higher proportion of American women must conceive at a weight within the range of normal BMI values. Second, a higher proportion of American women should limit their weight gain during pregnancy to the range specified in these guidelines for their prepregnant BMI.

Conceiving at a Normal BMI Value

Meeting this first challenge requires preconceptional counseling and, for many women, some weight loss. Such counseling may need to include additional contraceptive services (ACOG, 2005) to assist women in planning the timing of their pregnancies. Such counseling also may need to include services directed toward helping women to improve the quality of their diets (Gardiner et al., 2008) and increase their physical activity. This is because only a small proportion of women who are planning a pregnancy—and even fewer of those who are not planning a pregnancy but become pregnant nonetheless—comply with recommendations for optimal nutrition and lifestyle (Inskip et al., 2009).

Counseling is already an integral part of the preconception recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Johnson et al., 2006), which are designed to enable women to enter pregnancy in optimal health, avoid adverse health outcomes associated with childbearing, and reduce disparities in adverse pregnancy outcomes. The IOM report Nu-

trition During Pregnancy and Lactation: An Implementation Guide (IOM, 1992a) also includes practical guidelines for preconceptional care.

It is noteworthy that few intervention studies have evaluated ways to improve the nutritional choices of women of childbearing age (McFadden and King, 2008), so this is an area in which further investigation is necessary. There is, however, evidence that preconceptional counseling improves women’s knowledge about pregnancy-related risk factors as well as their behaviors to mitigate risks (Elsinga et al., 2008). In addition, there is also evidence that pre- and interconceptional counseling improves attitudes and behavior about nutrition and physical activity in response to behavioral interventions (Hillemeier et al., 2008).

Women with the highest BMI values may even require bariatric surgery to achieve a better weight before conception. Recent systematic reviews suggest women who undergo such surgery have better pregnancy outcomes than women who remain obese (reviewed in Maggard et al., 2008; Guelinckx et al., 2009).

Gaining Weight During Pregnancy Within the New Guidelines

Meeting this second challenge requires a different set of services. The first step in assisting women to gain within these guidelines is letting them know that they exist, which will require educating their health care providers as well as the women themselves. Government agencies, organizations that provide health care to pregnant women or those who are planning pregnancies, private voluntary organizations, and medical societies that have adopted these guidelines as their standard of care could all provide this education.

Women who know about the guidelines and have developed a weight-gain goal with their care provider may need additional assistance to achieve their goal. The IOM (1990) guidelines called for individualized attention, and the IOM report Nutrition Services in Perinatal Care (1992b) called for “basic, patient-centered individualized nutritional care” to be integrated into the primary care of every woman, beginning before conception and continuing throughout the period of breastfeeding. Guidelines on providing such care were provided in Nutrition During Pregnancy and Lactation: An Implementation Guide (IOM, 1992a). The increase in prevalence of obesity that has occurred since 1990 suggests that this recommendation has become only more important. However, as noted above, while individualized attention was an element in all recent interventions that have been successful in helping women gain within their target range, not every intervention with individualized attention has been successful. Clearly, additional services are needed. A number of kinds of services could be considered.

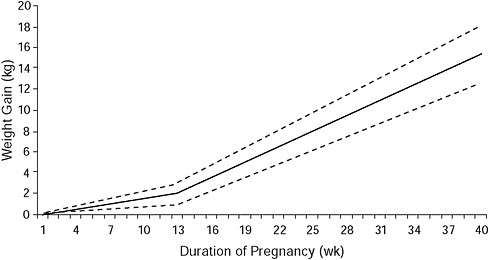

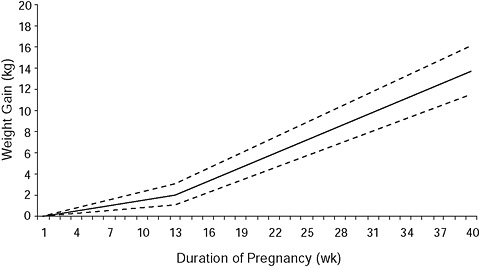

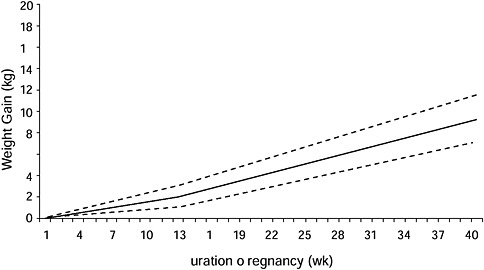

As noted in Chapter 7, health care providers should chart women’s weight gain and share the results with them so that they become aware of their progress toward their weight-gain goal. To assist health care providers in doing this, the committee has prepared charts (see Figures 8-2 through 8-5) that could be used as a basis for this discussion with the pregnant woman and could also be included in her medical record. These charts reflect the fact that typically only some weight gain usually occurs in the first trimester and that weight gain is greater and close to linear in the second and third trimesters (see Chapter 7 for the rates used in preparing these charts). The range around the target line in the second and third trimesters reflects the final width of the target range. In presenting these graphics, the committee emphasizes that graphical formats should be carefully and empirically tested before adoption to insure that the final product effectively communicates to women the intended messages about GWG.

These charts are meant to be used as part of the assessment of the progress of pregnancy and a woman’s weight gain and for looking beyond the gain from one visit to the next and toward the overall pattern of weight gain. This is because the pattern of GWG, like that of total GWG, is highly variable even among women with good outcomes of pregnancy (Carmichael et al., 1997). Carmichael et al. (1997) have recommended that women should be evaluated for modifiable factors (e.g., lack of money to buy food, stress, infection, medical problems) that might be causing them to have

FIGURE 8-2 Recommended weight gain by week of pregnancy for underweight (BMI: < 18.5 kg/m2) women (dashed lines represent range of weight gain).

NOTE: First trimester gains were determined using three sources (Siega-Riz et al., 1994; Abrams et al., 1995; Carmichael et al., 1997).

FIGURE 8-3 Recommended weight gain by week of pregnancy for normal weight (BMI: 18.5-24.9 kg/m2) women (dashed lines represent range of weight gain).

NOTE: First trimester gains were determined using three sources (Siega-Riz et al., 1994; Abrams et al., 1995; Carmichael et al., 1997).

FIGURE 8-4 Recommended weight gain by week of pregnancy for overweight (BMI: 25.0-29.9 kg/m2) women (dashed lines represent range of weight gain).

NOTE: First trimester gains were determined using three sources (Siega-Riz et al., 1994; Abrams et al., 1995; Carmichael et al., 1997).

FIGURE 8-5 Recommended weight gain by week of pregnancy for obese (BMI: ≥ 30 kg/m2) women (dashed lines represent range of weight gain).

NOTE: First trimester gains were determined using three sources (Siega-Riz et al., 1994; Abrams et al., 1995; Carmichael et al., 1997).

excessively high or low gains before any corrective action is recommended. The committee endorses this approach.

In addition to being made aware of their weight gain as pregnancy progresses through the use of weight-gain charts, women should be provided with advice about both diet and physical activity (ACOG, 2002). This may require referral to a dietitian as well as other appropriately qualified individuals, such as those who specialize in helping women to increase their physical activity. These services may need to continue into the postpartum period to give women the support necessary for returning to their pre-pregnant weight within the first year and for achieving normal BMI values before a subsequent conception.

Individualized nutrition services for pregnant women can be provided by a dietitian, as recommended in Nutrition Services in Perinatal Care (IOM, 1992b). Individualized dietary advice is also available for pregnant women on the Internet (see, for example, MyPyramid.gov [available online at http://mypyramid.gov/mypyramidmoms/index.html, accessed February 18, 2009]).

Individualized assessment of physical activity patterns and recommendations for improvement can be provided by a woman’s health care provider or by the type of trained practitioners that work in many health clubs and community-based exercise facilities. General advice on increasing physi-

cal activity is available on the Internet (see, for example, MyPyramid.gov [available online at http://mypyramid.gov/pyramid/physical_activity_tips.html, accessed February 18, 2009]), including advice specifically designed for pregnant women (available online at http://www.acog.org/publications/patient_education/bp045.cfm, accessed February 18, 2009). According to ACOG (2002), in the absence of either medical or obstetric complications, 30 minutes or more of moderate exercise a day on most, if not all, days of the week is recommended for pregnant women. Participation in a wide range of recreational activities appears to be safe for pregnant women, including pregnant women with diabetes (Kitzmiller et al., 2008). The recent report of the Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee (HHS, 2008) also supports physical activity during pregnancy. Based on the limited number of studies available, this group concluded that “unless there are medical reasons to the contrary, a pregnant woman can begin or continue a regular physical activity program throughout gestation, adjusting the frequency, intensity and time as her condition warrants.” The authoring committee of that report added that “in the absence of data, it is reasonable for women during pregnancy and the postpartum period to follow the moderate-intensity recommendations set for adults unless specific medical concerns warrant a reduction in activity.” However, the committee recognized that adequately powered randomized, controlled intervention studies on the potential benefits and risks of regular physical activity at various doses in pregnant women are urgently needed.

Individualized attention is likely to be necessary but not sufficient to enable most women to gain within the new guidelines. The limited information available on the link between community factors and GWG suggests that characteristics of neighborhoods influence women’s ability to gain weight appropriately during pregnancy (Laraia et al., 2007). For example, pregnant or postpartum women will have difficulty following advice to increase their physical activity by walking unless there is a safe place to walk in their community. Similarly, pregnant or postpartum women will have difficulty following advice to improve the quality of their diets unless healthy foods are available at local markets at prices they can afford. The family, and especially the partner, can also have a strong influence on maternal behaviors during pregnancy. Yet, at present, their influence on GWG is understudied and underutilized. As noted in the report Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Sciences (IOM, 2000), “It is unreasonable to expect that people will change their behavior easily when so many forces in the social, cultural, and physical environment conspire against such change.” As a result, these factors must also be addressed if women are to succeed in gaining within these guidelines. For example, hospital-based obstetric programs could link to community facilities with exercise programs for pregnant or postpartum women. Further research on these kinds of multilevel, ecological determinants of GWG (see Chapter 4)

is needed to guide the development of comprehensive and effective implementation strategies to achieve these guidelines.

Special attention should be given to low-income and minority women, who are at risk of being overweight or obese at the time of conception, consuming diets of lower nutritional value, and performing less recreational physical activity. The low health literacy levels that characterize this group also represent a major barrier for understanding and acting upon health recommendations (IOM, 2004). The use of culturally appropriate channels and approaches to convey this information at both the individual and population level is essential (Huff and Kline, 1999; Glanz et al., 2002). The community has a particularly important role to play in fostering appropriate GWG in low-income women. Approaches to consider range from social marketing (Siegel and Lotenberg, 2007) to improving the cultural skills of the health care providers that communicate GWG recommendations at an individual level (Haughton and George, 2008).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Although the guidelines developed as part of this committee process are not dramatically different from those published previously (IOM, 1990), fully implementing them would represent a radical change in the care of women of childbearing age. In particular, the committee recognizes that full implementation of these guidelines would mean:

-

Offering preconceptional services, such as counseling on diet and physical activity as well as access to contraception, to all overweight and obese women to help them reach a healthy weight before conceiving. This may reduce their obstetric risk, normalize infant birth weight, as well as improve their long-term health.

-

Offering services, such as counseling on diet and physical activity, to all pregnant women to help them achieve the guidelines on GWG contained in this report. This may also reduce their obstetric risk, reduce postpartum weight retention, improve their long-term health, normalize infant birth weight, and offer an additional tool to help reduce childhood obesity.

-

Offering services, such as counseling on diet and physical activity, to all postpartum women. This may help them to eliminate post-partum weight retention and, thus, to be able to conceive again at a healthy weight, as well as to improve their long-term health.

The increase in overweight and obesity among American women of childbearing age and failure of most pregnant women to gain within the IOM (1990) guidelines alone justify this radical change in care, as women clearly require assistance to achieve the recommendations in this report in

the current environment. However, the reduction in future health problems among both women and their children that could be achieved by meeting the guidelines in this report provide additional justification for the committee’s recommendations.

These new guidelines are based on observational data, which consistently show that women who gained within the IOM (1990) guidelines experienced better outcomes of pregnancy than those who did not (see Chapters 5 and 6). Nonetheless, these new guidelines require validation from experimental studies. To be useful, however, such validation studies must have adequate statistical power to determine not only if a given intervention helps women to gain within the recommended range but also if it improves the maternal and infant outcomes. In the future, it will be important to reexamine the trade-offs between women and their children in pregnancy outcomes related to prepregnancy BMI as well as GWG. It will also be important to estimate the cost-effectiveness of interventions designed to help women meet these recommendations.

FINDING AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Finding

The committee found that:

-

Existing research is inadequate to establish the characteristics of interventions that work reliably to assist women in meeting the 1990 guidelines for GWG or avoiding postpartum weight retention.

Recommendations for Action

Action Recommendation 8-1: The committee recommends that appropriate federal, state, and local agencies, as well as health care providers, should inform women of the importance of conceiving at a normal BMI and that all those who provide health care or related services to women of childbearing age should include preconceptional counseling in their care.

Action Recommendation 8-2: To assist women to gain within the guidelines, the committee recommends that those who provide prenatal care to women should offer them counseling, such as guidance on dietary intake and physical activity, that is tailored to their life circumstances.

Recommendation for Research

Research Recommendation 8-1: The committee recommends that the Department of Health and Human Services should provide funding for

research to aid providers and communities in assisting women to meet these guidelines, especially low-income and minority women. The committee also recommends that the Department of Health and Human Services should provide funding for research to examine the cost-effectiveness (in terms of maternal and offspring outcomes) of interventions designed to assist women in meeting these guidelines.

REFERENCES

Abrams B., S. Carmichael and S. Selvin. 1995. Factors associated with the pattern of maternal weight gain during pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology 86(2): 170-176.

Abrams B., S. L. Altman and K. E. Pickett. 2000. Pregnancy weight gain: still controversial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 71(5 Suppl): 1233S-1241S.

ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists). 2002. ACOG committee opinion. Exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Number 267, January 2002. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 77(1): 79-81.

ACOG. 2005. Committee opinion number 315, September 2005. Obesity in pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology 106(3): 671-675.

Asbee S. M., T. R. Jenkins, J. R. Butler, J. White, M. Elliot and A. Rutledge. 2009. Preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy through dietary and lifestyle counseling: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology 113(2 Pt 1): 305-312.

Carmichael S., B. Abrams and S. Selvin. 1997. The pattern of maternal weight gain in women with good pregnancy outcomes. American Journal of Public Health 87(12): 1984-1988.

Cedergren M. 2006. Effects of gestational weight gain and body mass index on obstetric outcome in Sweden. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 93(3): 269-274.

Claesson I. M., G. Sydsjo, J. Brynhildsen, M. Cedergren, A. Jeppsson, F. Nystrom, A. Sydsjo and A. Josefsson. 2008. Weight gain restriction for obese pregnant women: a case-control intervention study. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 115(1): 44-50.

Cogswell M. E., K. S. Scanlon, S. B. Fein and L. A. Schieve. 1999. Medically advised, mother’s personal target, and actual weight gain during pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology 94(4): 616-622.

Deierlein A. L., A. M. Siega-Riz and A. Herring. 2008. Dietary energy density but not glycemic load is associated with gestational weight gain. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 88(3): 693-699.

Elsinga J., L. C. de Jong-Potjer, K. M. van der Pal-de Bruin, S. le Cessie, W. J. Assendelft and S. E. Buitendijk. 2008. The effect of preconception counselling on lifestyle and other behaviour before and during pregnancy. Women’s Health Issues 18(6 Suppl): S117-S125.

Gardiner P. M., L. Nelson, C. S. Shellhaas, A. L. Dunlop, R. Long, S. Andrist and B. W. Jack. 2008. The clinical content of preconception care: nutrition and dietary supplements. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 199(6, Suppl 2): S345-S356.

Glanz K., B.K. Rimer and F.M. Lewis, Eds. (2002). Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 3rd Ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Gray-Donald K., E. Robinson, A. Collier, K. David, L. Renaud and S. Rodrigues. 2000. Intervening to reduce weight gain in pregnancy and gestational diabetes mellitus in Cree communities: an evaluation. Canadian Medical Association Journal 163(10): 1247-1251.

Guelinckx I., R. Devlieger and G. Vansant. 2009. Reproductive outcome after bariatric surgery: a critical review. Human Reproduction Update 15(2): 189-201.

Haughton B. and A. George. 2008. The Public Health Nutrition workforce and its future challenges: the US experience. Public Health Nutrition 11(8): 782-791.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2008. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Hillemeier M. M., D. S. Downs, M. E. Feinberg, C. S. Weisman, C. H. Chuang, R. Parrott, D. Velott, L. A. Francis, S. A. Baker, A. M. Dyer and V. M. Chinchilli. 2008. Improving women’s preconceptional health: findings from a randomized trial of the Strong Healthy Women intervention in the Central Pennsylvania Women’s Health Study. Womens Health Issues 18(6 Suppl): S87-96.

Huff R. M. and M. V. Kline, Eds. (1999). Promoting Health in Multicultural Populations: A Handbook for Practitioners. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Inskip H. M., S. R. Crozier, K. M. Godfrey, S. E. Borland, C. Cooper and S. M. Robinson. 2009. Women’s compliance with nutrition and lifestyle recommendations before pregnancy: general population cohort study. British Medical Journal 338: b481.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1990. Nutrition During Pregnancy. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1992a. Nutrition During Pregnancy and Lactation: An Implementation Guide. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1992b. Nutrition Services in Perinatal Care: Second Edition. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1995. The Best Intentions: Unintended Pregnancy and the Well-Being of Children and Families. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2000. Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Sciences. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2004. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Johnson K., S. F. Posner, J. Biermann, J. F. Cordero, H. K. Atrash, C. S. Parker, S. Boulet and M. G. Curtis. 2006. Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care—United States. A report of the CDC/ATSDR Preconception Care Work Group and the Select Panel on Preconception Care. MMWR Recommendations and Reports 55(RR-6): 1-23.

Kinnunen T. I., M. Pasanen, M. Aittasalo, M. Fogelholm, L. Hilakivi-Clarke, E. Weiderpass and R. Luoto. 2007. Preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy—a controlled trial in primary health care. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 61(7): 884-891.

Kitzmiller J. L., J. M. Block, F. M. Brown, P. M. Catalano, D. L. Conway, D. R. Coustan, E. P. Gunderson, W. H. Herman, L. D. Hoffman, M. Inturrisi, L. B. Jovanovic, S. I. Kjos, R. H. Knopp, M. N. Montoro, E. S. Ogata, P. Paramsothy, D. M. Reader, B. M. Rosenn, A. M. Thomas and M. S. Kirkman. 2008. Managing preexisting diabetes for pregnancy: summary of evidence and consensus recommendations for care. Diabetes Care 31(5): 1060-1079.

Kramer M. S. and R. Kakuma. 2003. Energy and protein intake in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD000032.

Langford A., C. Joshu, J. J. Chang, T. Myles and T. Leet. 2008. Does gestational weight gain affect the risk of adverse maternal and infant outcomes in overweight women? Maternal and Child Health Journal. Epub ahead of print.

Laraia B., L. Messer, K. Evenson and J. S. Kaufman. 2007. Neighborhood factors associated with physical activity and adequacy of weight gain during pregnancy. Journal of Urban Health 84(6): 793-806.

Maggard M. A., I. Yermilov, Z. Li, M. Maglione, S. Newberry, M. Suttorp, L. Hilton, H. P. Santry, J. M. Morton, E. H. Livingston and P. G. Shekelle. 2008. Pregnancy and fertility following bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association 300(19): 2286-2296.

McFadden A. and S. King. 2008. The Effectiveness of Public Health Interventions to Promote Nutrition of Pre-Conceptional Women. York, UK: NICE Maternal and Child Nutrition Programme.

Olson C. M. 2008. Achieving a healthy weight gain during pregnancy. Annual Review of Nutrition 28: 411-423.

Olson C. M., M. S. Strawderman and R. G. Reed. 2004. Efficacy of an intervention to prevent excessive gestational weight gain. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 191(2): 530-536.

Parker J. D. and B. Abrams. 1992. Prenatal weight gain advice: an examination of the recent prenatal weight gain recommendations of the Institute of Medicine. Obstetrics and Gynecology 79(5 Pt 1): 664-669.

Polley B. A., R. R. Wing and C. J. Sims. 2002. Randomized controlled trial to prevent excessive weight gain in pregnant women. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders 26(11): 1494-1502.

Power M. L., M. E. Cogswell and J. Schulkin. 2006. Obesity prevention and treatment practices of U.S. obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstetrics and Gynecology 108(4): 961-968.

Siega-Riz A. M., L. S. Adair and C. J. Hobel. 1994. Institute of Medicine maternal weight gain recommendations and pregnancy outcome in a predominantly Hispanic population. Obstetrics and Gynecology 84(4): 565-573.

Siegel M. and L. D. Lotenberg. 2007. Marketing Public Health: Strategies to Promote Social Change, 2nd Ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett.

Stotland N. E., J. S. Haas, P. Brawarsky, R. A. Jackson, E. Fuentes-Afflick and G. J. Escobar. 2005. Body mass index, provider advice, and target gestational weight gain. Obstetrics and Gynecology 105(3): 633-638.

Wolff S., J. Legarth, K. Vangsgaard, S. Toubro and A. Astrup. 2008. A randomized trial of the effects of dietary counseling on gestational weight gain and glucose metabolism in obese pregnant women. International Journal of Obesity (London) 32(3): 495-501.

Websites:

http://mypyramid.gov/mypyramidmoms/index.html

http://mypyramid.gov/pyramid/physical_activity_tips.html

http://www.acog.org/publications/patient_education/bp045.cfm