2

An Overview of Measures of Health Literacy

HEALTH LITERACY MEASUREMENT: MAPPING THE TERRAIN

Carolyn Clancy, M.D.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Several publications have raised awareness of the importance of health literacy to health and health care and have drawn attention to the need for measures of health literacy. For example, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) supported a systematic review of evidence about the relationship of health literacy and health outcomes. That report found that adults with lower health literacy have worse health care and poorer health outcomes. It also found that well-conceived interventions can improve the outcome of knowledge for those with both higher and lower literacy levels (Berkman et al., 2004). At approximately the same time the AHRQ report was released, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published a report of a study that assessed the problem of limited health literacy and considered next steps that should be taken in this field.1

In 2007, the AHRQ National Healthcare Disparities Report included, for the first time, findings on health literacy. These findings show that nearly

9 out of 10 adults may lack the skills needed to manage their health and prevent disease. Hispanic adults were 4.5 times more likely than white adults to have below-basic health literacy, and African American, American Indian, and Alaskan Native adults were nearly 3 times more likely than white adults to have below-basic health literacy (AHRQ, 2007).

Health literacy is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” (Ratzan and Parker, 2000). This definition focuses on individual capability, although it does imply needed skills.

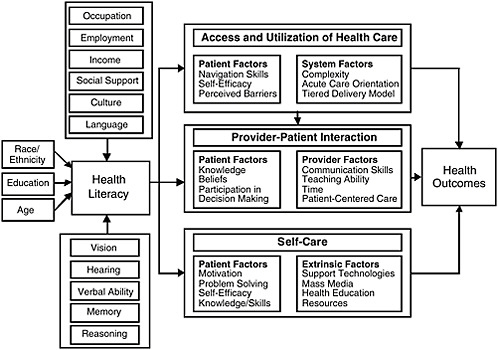

In the conceptual model shown in Figure 2-1, developed by Paasche-Orlow and Wolf (2007), health literacy, which is affected by sociodemographic characteristics as well as cognitive and physical abilities, is a determinant of health outcomes. As a determinant, health literacy affects a person’s ability to access and use health care, to interact with providers, and to care for himself or herself. Health literacy measurement has generally followed this model, focusing on measuring an individual’s capabili-

FIGURE 2-1 Causal pathways between limited health literacy and health outcomes.

SOURCE: Paasche-Orlow and Wolf, 2007. Reprinted by permission from PNG Publications, American Journal of Health Behavior, www.ajhb.org.

ties rather than actual skills and without reference to any interaction he or she may have with health information or the health care system.

Current Measurement Tools

The National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) was extremely important as the first national measure of literacy, providing systematic feedback to the education system and to the health care system about how literate American adults are. That feedback demonstrated that the level of information conveyed by these systems is not a good match with the abilities of most adults. The NAAL further identified substantial disparities associated with race and ethnicity, age, and insurance status.

While the NAAL provided an overall assessment of the level of literacy of American adults, various research measures have been used to establish the relationships among limited health literacy, health care, and health outcomes as well as the impact of interventions on individuals with limited health literacy. These measures include the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA) and the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM). Researchers have used these measures to conduct studies that have shaped the field of health literacy. For example, as mentioned earlier, researchers found that those with lower health literacy have poorer health care and health outcomes (Berkman et al., 2004). Baker and colleagues (2007) used the TOFHLA to determine that inadequate health literacy independently predicts all-cause mortality and cardiovascular death among elderly persons and that health literacy is a more powerful variable than education.

In the clinical practice setting, clinicians commonly overestimate the health literacy of their patients (Ryan et al., 2008). Assessing the health literacy of a sample of patients can provide the clinician with information about his or her patients’ average reading level, which then can be used as a guide in the selection and development of patient education materials. However, there is concern about universal testing. Some argue that such testing will alienate and stigmatize patients with limited health literacy. Others take the position that health care professionals must be aware of limitations in a patient’s ability to read or understand instructions so that care can be tailored for each patient.

Measurement Needs

Several fundamental questions need to be answered when assessing the state of the art of health literacy measurement:

-

How well do current approaches to measurement succeed in differentiating health literacy from literacy?

-

How well do current measures capture an individual’s ability to obtain, process, and use health information?

-

Are these measures sensitive to health care and public health improvement efforts?

-

Should disparities be included in the measures?

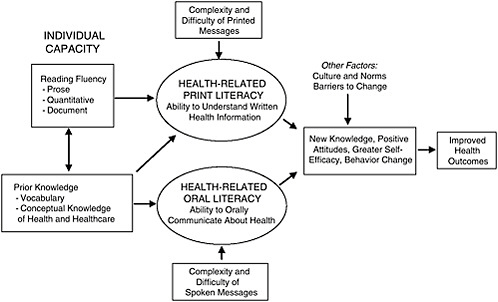

Baker (2006) developed a model that conceives of health literacy in the real world as a product of individuals’ capabilities and the demands of health information messages delivered by the health care system (Figure 2-2). In this model, the health care sector shares responsibility for making sure that individuals can use health information effectively.

The Baker model highlights an important question for health literacy measurement: What is the role of the health system in addressing issues of low health literacy? The health system has a responsibility to communicate and identify the correct strategies for caring for patients. It must teach adults the health-specific knowledge they need to take care of themselves and to make decisions about their health care. The system must simplify written and spoken health communications, and it must be reengineered

FIGURE 2-2 Conceptual model of the relationship among individual capacities, health-related print and oral literacy, and health outcomes.

SOURCE: Baker, 2006. Reprinted with kind permission from Springer Science + Business Media.

to reduce health literacy demands, from making the health system easy to navigate to making it easy to know how to avoid health risks and live a healthy lifestyle. Therefore, measures that would allow assessment of these responsibilities are key.

Yet if one thinks of health literacy as a determinant of health, then it is also important to improve individual capacity. To imagine that the problem of inadequate health literacy is solely a system problem ignores the fact that individuals engage with multiple systems in health care. Furthermore, efforts to improve health literacy have implications not only for solving patients’ acute problems in delivery of care today, but also for anticipating difficulties that patients will have as they continue to traverse the health care system. In other words, for a patient with a chronic illness, limited health literacy is not only a problem now, but is also going to be a problem for nearly anything that happens later.

What, then, are the implications for health literacy measurement? Measures of health literacy must go beyond individual reading capability in order to capture how well Americans understand what they hear and what they are told. First, there is a need to measure the ability to use health information to attain and maintain good health. This includes assessment of the following factors:

-

Oral understanding—how well individuals understand what they hear and what they have been told;

-

Health knowledge—whether individuals have adequate knowledge about prevention, medication, and self-care; and

-

Navigation skills—whether individuals are competent to access needed services, handle transitions, and find relevant information.

Second, health literacy measures need to guide quality improvement efforts. Such measures must be specific enough to provide information about the source of problems related to health literacy. They must also be sensitive enough to identify changes so that movement in the right direction can be detected. Third, measures are also needed to provide the information necessary to hold public and private health care organizations responsible for making health information understandable and actionable. No measures are currently available that can be used for accountability purposes. Finally, measures are needed that can be used with telephone surveys, thereby opening many research opportunities.

Promising Tools for Improving Health Literacy

There are promising approaches to improving health literacy. AHRQ and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute funded a random-

ized trial at the Boston University Medical Center, Department of Family Medicine, that was designed to educate patients about their post-hospital care plans.2 The program took about an hour of nursing time and about 30 minutes of pharmacy time. Results showed that patients assigned to the reengineered hospital discharge program (RED) had 30 percent fewer subsequent emergency visits and readmissions (Jack et al., 2009). Ongoing RED research is testing the automation of patient education through the use of an avatar. The challenge is integrating such programs into practice.

AHRQ is also testing several supplements to the ongoing Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) surveys3 that can be used to assess the health literacy friendliness of hospitals and physician practices. AHRQ has also developed some pharmacy literacy tools designed to help pharmacists better serve their low-health-literacy patients.4 Another tool is a guide for developing and purchasing information technology that is accessible to populations with limited health literacy.5 Finally, AHRQ has been working with the Ad Council to develop messages that inform individuals about what they can do to play a more active role in their own health and health care.6

Conclusion

Health literacy is not an individual problem, Clancy stated. It is a societal problem that should be addressed by making sure health information and services meet the needs of the public. To assess whether that is

|

2 |

The intervention included nurses working with in-hospital patients to make “follow-up appointments, confirm medication reconciliation, and conduct patient education with an individualized instruction booklet that was sent to their primary care provider. A clinical pharmacist called patients 2 to 4 days after discharge to reinforce the discharge plan and review medications. Participants and providers were not blinded to treatment assignment” (http://www.annals.org/cgi/content/abstract/150/3/178). Accessed April 5, 2009. |

|

3 |

“The Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) program is a public-private initiative to develop standardized surveys of patients’ experiences with ambulatory and facility-level care” (https://www.cahps.ahrq.gov/default.asp). Accessed April 5, 2009. |

|

4 |

Additional information can be found at http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/pillcard/pillcard.htm, http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/pharmlit/index.html, http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/pharmlit/pharmtrain.htm, and http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/callscript.htm. |

|

5 |

Additional information can be found at http://healthit.ahrq.gov/portal/server.pt?open=514&objID=5554&mode=2&holderDisplayURL=http://prodportallb.ahrq.gov:7087/publishedcontent/publish/communities/k_o/knowledge_library/features_archive/features/accessible_health_information_technology__it__for_populations_with_limited_literacy__a_guide_for_developers_and_purchasers_of_health_it.html. |

|

6 |

Additional information can be found at http://www.ahrq.gov/questionsaretheanswer/. |

occurring requires accurate, meaningful health literacy measures. Characteristics of such measures are the following:

-

The goals of every health literacy measure are very clear;

-

Measures are developed in a way that enables movement upstream to levers of change;

-

The system is responsive to specific literacy needs; and

-

Measures provide information about quality or the “what to do.”

Measuring health literacy is incredibly important. What must be done now is to identify the most practical and sensible way to move forward with developing and implementing important measures.

THE IMPORTANCE OF A NATIONAL DATASET FOR HEALTH LITERACY

Marin P. Allen, Ph.D.

Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health

Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion (IOM, 2004) laid out the questions that have been raised in the field recently over the issue of how the needs and skills of the provider as well as the individual impact health literacy. That report stated, “Health literacy emerges when the expectations, preferences, and skills of individuals seeking health information and services meet the expectations, preferences, and skill of those providing information and services. Health literacy arises from a convergence of education, health services, and social and cultural factors…. Approaches to health literacy bring together research and practice from diverse fields” (IOM, 2004).

Increasing health literacy is one of the objectives of Healthy People 2010 (HP 2010), which is a multidecade national agenda for disease. The HP 2010 objectives provide a foundation for national research and action, including data collection. Currently, HP 2010 uses the NAAL assessment as its data source for information on health literacy. It is important to note that baseline and target data are expected for all objectives that will be included in the new Healthy People 2020. Without baseline and target data, there will be no objective.

Having the health literacy objective in HP 2010 has yielded several positive results. For example, there has been a Workshop on Improving Health Literacy organized by the Office of the Surgeon General, as well as Town Hall meetings on improving health literacy in several states including California, Missouri, and New York. There is a National Action Plan on Improving Health Literacy, and many professional societies (e.g.,

American Dental Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians Foundation, and American Medical Association) have begun to focus on improving health literacy.

Additionally, a number of research efforts in health literacy have been funded in response to program announcements from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), AHRQ, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sabra Woolley of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and her postdoctoral student, Shaniece Charlemagne, examined NIH and AHRQ funding of health literacy and health disparities research. Interconnected health literacy and health disparities research funded through NIH and AHRQ grants is intended to involve health literacy as a key outcome, health literacy as a key explanatory variable for other outcomes, and prevention/intervention strategies that focus on health literacy. Woolley and Charlemagne found that more than half of the NIH and AHRQ grants primarily study the adult population. Race/ethnicity, gender, and special populations are more likely not to be specified within the abstract of grants funded. Of the grant abstracts that do specify population to be studied, African Americans, females, and low-literacy populations were the primary targets.

The NIH- and AHRQ-funded research projects are more likely to be supported through R017 and R038 funding mechanisms. Within the NIH and AHRQ, the NCI has provided more funding since 2006 to grants that address health literacy and health disparities than the other institutes and centers. Approximately 20 percent of the funded grants proposed use community-based participatory research or community-based research methods. However, only 6 percent of the abstracts identified a measurement methodology. In addition, special interest areas that have been funded primarily are “Cancer” and “Other” interest areas (i.e., risk behaviors, mental health, risk factors, child health and injury prevention, science education, etc.).

Woolley and Charlemagne concluded that grants funded by the NIH and AHRQ present various themes, patterns, and funding opportunities. The different ways in which the NIH and AHRQ afford researchers the opportunity to address health literacy issues ultimately will contribute to a reduction in health disparities among various populations. It was also

|

7 |

“The Research Project Grant (R01) is the original and historically oldest grant mechanism used by NIH. The R01 provides support for health-related research and development based on the mission of the NIH. R01s can be investigator-initiated or can be in response to a program announcement or request for application” (http://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/r01.htm). Accessed April 6, 2009. |

|

8 |

“The R03 award will support small research projects that can be carried out in a short period of time with limited resources” (http://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/r03.htm). Accessed April 6, 2009. |

suggested that there is a need for researchers to specify, within the funded grant abstracts, the population studied (i.e., race/ethnicity, gender, etc.), measurement methodology, and research methodology used.

Healthy People 2010, in many ways, defined what is needed to move forward in health literacy. A key issue has been a data source that is national, provable, and demonstrable. According to HP 2010, individuals are health literate when they possess the skills to understand information and services and use them to make appropriate decisions about health. Without the NAAL data, there is no ability to track health literacy skills over time at a national level.

Of paramount importance is the need for a national, consistent dataset that provides information necessary to track changes in health literacy over time. The difficulty for measurement at the national level, however, has been to determine how big a picture is needed and what should be included in that picture. Numerous factors could be measured. Health literacy pervades health issues at all levels—prevention, diagnosis, intervention, and cure for both chronic and acute diseases. Health literacy also pervades social issues—disparities, cultural differences, language differences, and access issues. There is also economic strain, both on the individual and on the system, in terms of lost human capital, lost time, and money.

Information about the interactions of individuals with limited English proficiency (LEP) with the health care system is another area for measurement. Patients with LEP encounter difficulties as they attempt to interact with clinicians, but the extent and characterization of the problem are unknown. The 2000 Census counted 20 million people who speak English poorly and 10 million who speak no English (Newman, 2003). The White House Office of Management and Budget, in a 2002 report, estimated the number of patient encounters across language barriers each year at 66 million (Newman, 2003).

In terms of minorities, the Census projects that by 2042, more than 50 percent of the U.S. population will consist of minorities. For children, the figures are even more pronounced. Today, children who belong to a minority racial or ethnic group make up 44 percent of the U.S. population of children. By 2023 that figure will grow to more than half of America’s children, and by 2050 that figure will be 62 percent (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2008).

Considerations for health literacy measurement should include the capacity of people with LEP and the capacity of systems to respond to them. Currently there are no national data on health literacy for people who speak other languages or have LEP. This is a major gap.

Literacy is not a constant. It changes over time. Older adults who may have had fine reading, writing, and thinking skills in younger days

may have difficulty reading and understanding information as they age. For people 65 and older, 66 percent have poor literacy skills. Vision problems, poverty, learning disabilities, immigration and minority status, and poor education also can contribute to low literacy. National data are needed that can track changes over time in multiple populations.

There is a need for national data to support a Healthy People 2020 objective. Furthermore, there is a need for population- and systems-based data. Some people have said that if there are no data, there is no problem. Without national data on the extent and characteristics of health literacy in America, Allen said, it will be impossible to develop effective interventions that lead to improving the health literacy of the 90 percent of the population who, the NAAL data show, do not have the skills necessary to understand information and services and use them to make appropriate health decisions.

NAAL DATA: TO USE OR NOT TO USE?

Barry D. Weiss, M.D.

University of Arizona College of Medicine

As mentioned previously, the NAAL database is currently the only database with national data about health literacy. But how easy is it to use this database, what kinds of problems do researchers encounter, and what suggestions might be offered for improvement?

If one accesses the National Assessment of Adult Literacy Data Files website (http://nces.ed.gov/NAAL/datafiles.asp), one finds a link to click in order to access the public use files. Clicking on that link, one then receives a message box asking, “Do you want to open this file?” When one clicks “open,” however, one receives a message box that says, “Windows cannot open this file.”

At this point one might turn to the Public Use Data File User’s Guide for instructions about how to access the public use files. This user’s guide is 882 pages long. For many people attempting to use the NAAL data, this is their interface experience—they get a file that will not open and if they want to find out what to do they have to read an 800-page book.

To prepare for this presentation, Weiss said, he sent an e-mail to 10 individuals whom he considers the top health literacy researchers in the country. He asked them the following questions: Have you used the NAAL data, and if so, tell me about your experience? How easy are they to use? Did you encounter any problems and, if so, what were they? The researchers’ responses follow.

Researcher #1

For the most part it is fairly easy to use. I’ve been using SAS [a computer program], but have used their interface tools to generate the code, which is a great resource. The documentation seems complete and has been very useful. We contacted NAAL to request a Census-tract crosswalk to the restricted-use dataset so we could use rural-urban commuting area (RUCA) codes for rural status designation (instead of the metropolitan statistical area [MSA] or non-MSA variable). They were responsive to our request for this information, and I don’t recall that there were any “orphans”—all of the data had a corresponding Census tract. However, for our use considering rural literacy in Arizona, it became apparent that all of the Arizona data were collected only in Pima (Tucson) and Maricopa (Phoenix) counties. Seventeen states (including Arizona) did not have any non-MSA data. The rural data came disproportionately from the South and Midwest (only 8 percent of the records from the Northeast are “non-MSA”—from Pennsylvania, New York, Maine, Massachusetts—and from only 1 percent of Massachusetts’s records). There were six records in the dataset that were apparently from California but classified as being from the Midwest.

Overall, then, researcher #1 had a positive experience with the NAAL data, with only minor comments about the rural data being collected in urban counties and the misclassification of some data from California as being from the Midwest. The same cannot be said for the other researchers who responded.

Researcher #2

The fact that they [NAAL] excluded people who are unable to read at all is problematic from the point of view of determining prevalence. Changing the categories/scaling from NAAL limits comparisons over time. But the biggest issue is the fact that they do not release individual-level data for investigation.

If one wants to find the prevalence of limited literacy, excluding people who cannot read from the sample is not a good idea. Changing the categories in the 2003 NAAL from those used in 1992 makes it difficult to compare trends and changes over time.

During the discussion period, one participant said the NAAL did not exclude people who could not read. Those excluded were people who could not communicate in English or Spanish. But other individuals who were able to complete the demographic information—either in writing or orally—were included, and they would have been put in the below-basic category if they could not complete the test. Another thing the NAAL did, for those who were clearly going to be unable to complete the standard questionnaire, was to use an easier test instrument. This was done to try to differentiate among people at the low end of the spectrum.

Researcher #3

Statistical analyses can only be reliably “run” using AM software. AM software is free, but only includes a small number of statistical tests. Because so few people have used or know how to use AM software, if you need help interpreting the output, you’re pretty much stuck. The collection of health-related items is relatively small. There are questions regarding where one obtains health-related information and receipt of general screening (e.g., vision, dental, Pap tests). In the future, it would be great if NAAL data could be linked to robust health-related data (e.g., Medical Expenditure Panel Survey [MEPS], Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey [BRFSS], etc.).

Researcher #4

I did try [to use the NAAL data] shortly after it was released and ran into many difficulties with trying to get any answers/response to my inquiries about using/accessing the data. I also found it particularly troublesome to not be able to find out the exact wording of the questions. It seemed like NAAL was all operating with so many secrets and no interest in making the data available to advance our knowledge of health literacy. I have not since attempted to use/access the data.

Researcher #5

[We] need detail of what NAAL categories correspond to having limited literacy or health literacy. Having seen specific questions and data for a few NAAL items, my sense is that the data are not helpful and not credible. Health-services use items were flawed.

Researcher #6

I provide frequent health literacy/plain language trainings for health professionals, and I am always asked what “grade levels” are represented by the four NAAL reporting categories. I know that the concept of grade levels is not precise, to say the least, but people want a quick and easy way to grasp the magnitude of the literacy/health literacy problem. It would also allow us to use readability scores to more effect. Sometimes it’s the ONLY way to get people to take action—to point out that all their materials are written at high school and college reading levels (which they usually are) and their patients read far below that level.

Conclusions

Of the 10 researchers from whom information was requested, 4 had not used the NAAL database. The remaining 6 provided information

about their use of the database. One can conclude from these responses that the data are difficult to access or use, with the one exception being the response of the statistician (Researcher #1). A better option than what now exists is to house the database in a standard statistical program rather than an obscure program that few know how to use. Most attempting to use the database have not had the perseverance to find the data needed, even though those data might exist. Furthermore, a quick reference guide is needed, not an 882-page instruction booklet.

The responses also indicate a lack of confidence in the validity of the data. There is concern about sampling (rural, distribution across states). Additionally, it would probably enhance confidence in the validity of the survey if the questions were released so that researchers could see what was actually asked. Finally, the results are not translatable to education of health professionals because data are provided in a statistical database rather than in a form that people want to use—for example, by grade level.

In general, Weiss concluded, researchers find the data hard to obtain or use, and they do not trust the data.

HEALTH LITERACY MEASUREMENT: A BRIEF REVIEW AND PROPOSAL

Andrew Pleasant, Ph.D.

Rutgers University

Health literacy is an important and powerful tool for improving health. Yet health literacy measurement is incomplete. Adequate and accurate health literacy measurement is important because with such measures, appropriate attention to the importance of health literacy can be demonstrated. Furthermore, such attention can lead to funding of efforts to improve health literacy, and that can, in turn, lead to change in health systems. Health literacy can be both a theoretical and empirical guide to how, where, when, and why that change should occur.

A number of different tools are available that are meant to address health literacy. Yet these tools are incomplete. The tools include

-

NAAL: National Assessments of Adult Literacy, health literacy component

-

HALS: Health Activities Literacy Scale

-

REALM: Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine; now REALM Spanish, REALM Teen

-

TOFHLA, S-TOFHLA, “Adapted” TOFHLA: Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults

-

NVS: Newest Vital Sign

-

The single (or three) item screeners

-

SAHLSA: Short Assessment of Health Literacy for Spanish-speaking Adults

-

SIRACT: Stieglitz Informal Reading Assessment of Cancer Text

-

MART: Medical Achievement Reading Test

-

FHLM: Functional Health Literacy Measure

-

ELF: Health literacy screener

Although these are described as tools to measure health literacy, most are actually screening tools. There is a fundamental difference between screening and measurement. The goal of screening is to divide people into healthy and sick categories (have/have not). Screening does not tell what is actually wrong with the patient; it is both under- and overdiagnosis because what is required in screening in clinical contexts is a tool that is short, quick, and easy to use.

Measurement, on the other hand, is an attempt to explore in depth the structure and function of objects of interest. In fact, a true measure should establish the basis for a reliable screening tool. The purposes of measurement are to

-

Advance knowledge—i.e., test hypotheses;

-

Explore and explain structure and function;

-

Monitor effectiveness and equity of interventions;

-

Indicate major problems confronting society; and

-

Contribute to setting policy goals.

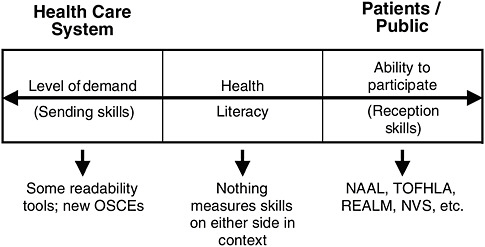

When one thinks of measurement and health literacy, one often thinks of the capability of individuals. Yet there is another component to health literacy, which is the health care system as shown in Figure 2-3.

On the health care system side of Figure 2-3, current measurement is in terms of readability tools that assess level of difficulty in language. On the other side of the figure, the patients/public side, available tools are those in the long list above. None of these tools, however, measures health literacy in the context of both the health care system and the patient/public. This is a critically important issue, especially for attempts to self-report literacy or health literacy, which serve as both dependent and independent variables. Some people overestimate their literacy skills, when in fact they may just be avoiding challenges—for example, no traveling, no attempts to learn new things, no visits to a physician.

Another major difficulty with current measures is that, using data from any of the currently available tools, the data do not describe how health literacy causes improved health. There are data about what happens

FIGURE 2-3 Health care system and patients/public.

SOURCE: Pleasant, 2009.

when health literacy is not present, there are correlational data, but the actual structure of the mechanism, how it is that health literacy leads to improved health, has yet to be shown.

A Comprehensive Measure of Health Literacy

There is currently no open-access (free/easily available) comprehensive measure of health literacy. But there should be. A comprehensive measure of health literacy does not mean a measure that includes everything. Comprehensive means showing extensive understanding. A comprehensive measure builds a foundation of knowledge that is needed to enable accurate screening and to advance health literacy as a tool to improve health and reduce inequities in health. A comprehensive measure is one that consists of items that test a theory, a framework, or a definition of health literacy.

To build a comprehensive measure of health literacy, those in the field must agree on exactly what should be measured. A commonly agreed-upon definition of health literacy is needed. Although the Ratzan and Parker definition promulgated in the IOM report Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion (2004) is often used, there are many in the field, including some who served on that IOM committee, who believe this definition is insufficient. It was good for the time, but the field has progressed.

In arriving at a comprehensive measure of health literacy, the process is as important as the product. As the process for building the measure of

health literacy proceeds, two things must be kept in mind. First, one must remember the broader context in which health literacy operates. This is important from a research perspective because when the point is reached that longitudinal studies can be conducted, measures must be able to demonstrate that change is due to change in health literacy, not a change in the larger context in which health literacy operates.

The second point to keep in mind is that health literacy is a social construction. It exists solely because of social interaction. Health literacy should not be treated, as it often has been, as a biomedical issue with social roots. Rather, it is a social issue with biomedical implications. Therefore, the tools of social research are required for measurement.

Eight Proposed Methodological Principles

Eight principles of social research are needed in the development of a new and comprehensive measure of health literacy. The comprehensive measure must

-

Be built explicitly on a testable theory or conceptual framework of health literacy;

-

Be multidimensional in content;

-

Use multiple methods;

-

Clearly distinguish health literacy from communication;

-

Treat health literacy as a “latent construct”;

-

Honor the principle of compatibility;

-

Allow comparison; and

-

Prioritize social research and public health applications versus clinical use.

First, a comprehensive measure must be built explicitly on a testable theory or conceptual framework of health literacy. Currently, there are about five or six models, two of which were presented earlier. There are many points of agreement among these models and several points of disagreement. None of the current measurement tools, however, were built to actually test and advance any of the models, frameworks, or theories. There needs to be a renewed consensus about the theory or conceptual framework of health literacy in order to develop a comprehensive measure of health literacy.

Second, the conceptual framework of health literacy needs to be multidimensional in context. Most theories or conceptual frameworks define health literacy as a construct with multiple conceptual domains and multiple skills and abilities. Conceptual domains include fundamental, civic, science, culture, critical, and communicative. Skills and abilities include

finding, understanding, evaluating, communicating, using, navigating, prose, document, quantitative, and speech. Furthermore, the elements of the underlying construct should be explicit in a measure.

Third, multiple measures must be used because there is a huge difference in the skills between recognizing and understanding a letter, a word, a sentence, a paragraph, or a document or narrative. Navigating information in the health care system requires a range of skills.

Fourth, health literacy must be clearly distinguished from communication. Communication is a symbolic transactional process. Most of the functional definitions of health literacy involve the use of skills and abilities. Communication and health literacy can and should be distinguished from one another, yet a number of the current attempts to evaluate and address health literacy make no distinction.

Fifth, health literacy should be treated as a latent construct.9 Health literacy is not explicit, that is, one cannot “see” health literacy, and it varies across individuals and contexts. Therefore, health literacy should be considered a latent construct for measurement purposes. This means a new measure should contain items that sample from all the conceptual domains outlined by the underlying theory or conceptual framework.

Sixth, honor the principle of compatibility. A measure of health literacy that focuses solely on the clinical setting is inappropriate when researching public health behaviors and outcomes. For a hypothesized relationship among attitudes, behaviors, and knowledge to hold true, the three components must be measured at equivalent levels in regard to action, target, context, and time (Fishbein and Ajzen, 2005).

Seventh, allow comparison across contexts and languages including culture, life course, population group, and research setting. This implies that the measure be adapted or developed in parallel in different target languages and different contexts. One can think of a measure of health literacy as a core module with add-on modules to address specific states. The modules are all built on the same theory, so they are comparable across a multitude of different states. For example, one could have a health literacy module about diabetes, about aging, or about AIDs. As long as they are built on the same theoretical basis, they are comparable.

Eighth, prioritize social research and public health applications versus clinical use. It is time to dedicate resources toward building a complete measure of health literacy if the following factors are understood:

-

Health literacy is an important determinant of public and individual health;

-

There is a risk of harm in labeling individuals as “low health literate” in a clinical setting;

-

Several screeners already exist;

-

The time burden on clinical settings limits ability to measure versus screen; and

-

A simple tool is limited in its ability to advance knowledge of a complex social process.

To accomplish the task of building a comprehensive measure of health literacy, consensus, scientific methods, and leadership funding are needed. Social constructions are defined through a social process, through consensus. Health literacy is a relatively new idea and is being continually defined in words and actions. A great deal of progress has been made, but if a comprehensive measure is to be developed, it is time for a consensus about the theory and conceptual framework of health literacy.

A comprehensive measure of health literacy should use the scientific method, that is, the measure should explicitly test the definition of the social construct of health literacy. No current screening tool of health literacy was explicitly designed to test any of the more commonly accepted definitions of health literacy.

Finally, there must be research-funding leadership. A good deal of research has been conducted on health literacy, but those projects are using a variety of tools without an actual consensus on the depth and strength of health literacy. This could lead, further down the road, to an even more disjointed field than currently exists, with findings that are not comparable. Many screening tools are available, but what is needed is a comprehensive, usable, freely accessible measure of health literacy. Developing such a measure requires the kind of process described earlier. It is critical, Pleasant said, that funding organizations take the lead in funding a renewed consensus process about health literacy and support development of measures based on that process.

DISCUSSION

Moderator: George Isham, M.D., M.S.

HealthPartners

National Assessment of Health Literacy

One person drew attention to the fact that the Healthy People 2020 process is ongoing and is being conducted by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services (HHS). For that process, national-level data on health literacy are needed. However, the NAAL, which is managed by the Department of Education (DOE) and is currently the only source of national data on health literacy, is not slated to be implemented again until 2015. These two processes are out of synchronization. Therefore, at the very least, there is a need for coordination between HHS and DOE.

Another participant raised the issue that the fact that the NAAL data are collected by and housed in DOE creates some difficulties. Several other efforts to measure and collect health literacy data are also under way. Is there a need for an ongoing data collection system for health literacy that is owned and operated within HHS? Would this help move the issue forward?

Clancy said that what is clearly needed is a strategy. Whether that strategy is solely owned by HHS or shared with others is not clear. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, Public Law 111-5, 111th Congress, 1st session (February 17, 2009), has brought many new demands and opportunities. Language in the Act provides for new resources for health information technology and federal investment in collection of data on patient race, ethnicity, and primary language. Should health literacy measures be built into what is being developed in electronic records or as part of information collected on quality measures, or should health literacy be treated more as a vital statistic? There is no answer to that question as yet. But there is a unique opportunity for clinical care and public health to be thinking together about what might be a joint approach.

One participant said that what was particularly troubling about the comments on the NAAL were the questions regarding the validity of those data. She asked whether Weiss had a prescription for remedying the problems with the NAAL. Weiss responded that there was mistrust of the sampling methods and great concern over the fact that the survey questions are not available. Why not release the questions on the survey? Some of the researchers’ concerns might evaporate if the information was released. Then they could make judgments about what to use, or, with the information in hand, they might think that their concerns were overblown. But refusing to release the questions induces cynicism in the users.

Another participant asked what Weiss would like to see in terms of national data and what would help in his research. Weiss said what is needed is a measure of health literacy that is known to be reliable and valid when used with the same people over and over across time. The TOFHLA, REALM, NVS, and all other current health literacy instruments are all meant for one-time assessments of individuals’ health literacy skills. But conducting research that shows that improving health literacy improves outcomes requires a reliable and valid measure of health literacy that can be used longitudinally.

The NAAL questions offer that potential. The NAAL was implemented in 1992 and 2003, and could be implemented again. Many believe there are reliable and valid questions in the NAAL that can be used to assess literacy over time to see if there are changes. This may be the only set of questions that has that characteristic. If there are valid questions regarding health literacy, this could be a very powerful tool. But we do not know what the questions are, and the data are very difficult to access and use.

Weiss said if that is the case, then researchers such as those who responded to his simple questionnaire are misinformed. Such misinformation raises the question of the need for better communication between the NAAL and researchers. Different researchers have different understandings of what data were collected and what are available. The information about what the survey was about and what is actually in the survey has not been transmitted effectively.

One participant said the complexity of the NAAL does not seem too dissimilar from that of other large national datasets where it is important to have available assistance from someone who really knows how to navigate that dataset. However, the secrecy over the health literacy questions is a serious problem because it prevents more specific analyses on the implications of health literacy. Weiss agreed and said there is no reason the questions should not be released.

Another participant suggested that one of the problems with a database such as the NAAL is that it is isolated from health outcomes and other health information. Someone else stated that one other factor missing in the NAAL is the ability to measure quality of care and relate that to health literacy and health outcomes. The federal government, he continued, has an opportunity to begin to focus on a meta-organization of its various databases in ways that are usable, not only to researchers, but to the general public and to care delivery systems across the country. Weiss agreed that such linkage would be valuable because then one could examine health literacy data in relationship to known health outcome data.

One participant concluded the discussion with a series of questions. If the NAAL data are not adequate, and if the DOE implemented the health literacy supplement as an add-on to its original assessment of adult literacy, what happens next? Where should the locus of decision making be to create the data that the field believes are necessary? What are reliable and valid measures of health literacy? How can the data be made accessible and transparent? What is needed to facilitate economic analyses of the impact of low health literacy?

Accountability

One participant referred to the portion of Clancy’s speech where she talked about the need for health system accountability in health literacy. For example, what are the barriers to including health literacy as a component of all federal research grants, just as is done now for minorities? Are there other approaches to these new comparative effectiveness activities that would make health literacy fundamental to the activities? Clancy said she did not think the issue is one of barriers; rather it is an issue of knowing what should be measured. For example, having a way to measure what patients hear in their interactions with providers rather than what the providers do is very complex.

Another participant asked Clancy, given the importance of health literacy to quality, how effective has The Joint Commission been in embracing health literacy and health literacy measurement? Clancy responded that The Joint Commission has been acutely aware of this issue and has sponsored a number of policy roundtables on it. As one thinks about how health literacy relates to quality measurement, it is important to identify next steps that could be taken with both The Joint Commission and other potential stakeholders.

One participant asked what would be involved in including health literacy in the required Joint Commission quality measures. Clancy responded that the supplements to CAHPS are a starting point. Amy Wilson-Stronks of The Joint Commission said the Commission is continuing work in the area of health literacy through the IOM Roundtable on Health Literacy and the continuing emphasis on culture and language.

Other Issues

A participant asked whether the relationship between behavioral health issues and health literacy has been examined. The participant’s health system has a large proportion of patients who are older and who have multiple chronic conditions as well as behavioral health diagnoses. The participant asked how health literacy measures and interventions could be designed to address such patients.

Clancy said it is logical to assume there is an interaction between behavioral health issues and health literacy. AHRQ has an initiative that has focused on the needs of complex patients, defined as people with multiple chronic illnesses. If one of those illnesses is a behavioral health issue, a situation becomes much more complicated in terms of factors such as the ability to cope with health care demands and the information needed to care for oneself.

One area of AHRQ’s focus in the development of the hospital CAHPS instrument in health literacy is the patient’s ability to care for

himself or herself after leaving the hospital. Hopefully, some of those measures will capture when a patient is not able to care for himself or herself and determine what supports are in place for both mental and physical health.

One participant referred to the new push for comparative effectiveness research. She said that one fear is that such research will be interpreted in a narrow way. How can one think of the comparative effectiveness of different approaches to health literacy, both within the health care system and in communities? How can those involved in the issues of health literacy communicate better about the serious research needed to understand the approaches to health literacy and comparative effectiveness research?

Part of the AHRQ mandate, Clancy said, is to produce information that is accessible to a broad number of audiences. There is a center that tests a variety of modes for effective communication, with a particular focus on audiences with limited health literacy. They have made a fine start, but have a way to go. Sufficient resources have not been available to evaluate different approaches. One of the sections of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 directs that the IOM make recommendations about national priorities for comparative effectiveness research.10 The IOM will hold a public hearing on this issue. It would be important to get health literacy on the agenda of this meeting early.

Health literacy is not constant over one’s lifetime, one participant said. It will vary with factors such as the level of stress and health conditions. This is a real problem from a measurement perspective. If one is collecting national-level data, then one would expect these variations to even out—that is, some are having a bad health literacy day while others are having a good health literacy day. But implementing health literacy measurement for an individual in order to tailor care presents a different measurement challenge.

Weiss agreed that it is definitely more difficult at the individual level. The finding that people with low health literacy have worse health indicators and higher costs has been established. The big question is, if an individual’s health literacy is improved, are the health outcomes better? Unless it can been shown that health literacy has improved, it can never be shown that health outcomes have improved as a result of improved health literacy. Therefore, an instrument is needed that can be used to show

|

10 |

“That the Secretary shall enter into a contract with the Institute of Medicine, for which no more than $1,500,000 shall be made available from funds provided in this paragraph, to produce and submit a report to the Congress and the Secretary by not later than June 30, 2009, that includes recommendations on the national priorities for comparative effectiveness research to be conducted or supported with the funds provided in this paragraph and that considers input from stakeholders” (http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=111_cong_bills&docid=f:h1enr.pdf). Accessed April 5, 2009. |

health literacy changes over time, an instrument that can be depended on as valid and reliable for what it is intended to measure.

Developing such an instrument, Weiss said, might simply be a matter of validating some of the existing tools. Perhaps the NAAL has the best potential, but that is unknown because the questions remain unavailable and data remain difficult to access and use.

Another participant said that many standardized tests, such as the NAAL, are essentially a knowledge-deficit model of assessment. In other words, they measure what people do not know rather than what they do know. As a replacement, some people advocate standardized tests that measure engagement or interest in, for example, one’s own health care. Other measures could be included that indicate an individual’s intention or proclivity to learn more.

Weiss said he was familiar with the concept of empowerment, which is what the questioner seemed to be suggesting. For example, there are those who assert that low health literacy is consistent with a low sense of self-empowerment and an external locus of control. Those with low literacy tend not to be those who believe they can take charge of their lives or have the ability to do so. The question is, what does one measure? Maybe the test of health literacy is to measure this proclivity for self-empowerment. There are scales of empowerment. There are scales of locus of control. These things do exist, and they might be incorporated into a health literacy measure to make it more comprehensive.

One participant asked how one could tie health literacy tools to self-management training for prevention efforts. For example, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has entered into an agreement to provide training and education for those who have chronic kidney disease and diabetes. As CMS looks to expand its training efforts, could a health literacy assessment tool be used to increase the effectiveness of the CMS action plans and, thereby, hopefully improve health outcomes? Allen replied that adding a health literacy assessment tool would be an exciting opportunity for research, an opportunity to assess—both at the beginning of the project and at the end—what actually has been accomplished.

Another participant added that AHRQ is developing a universal precautions health literacy tool kit to help clinicians in their practices. Once a clinician understands that there is a health literacy problem, this collection of tools, with brief guidance on how to use them, can help integrate health literacy work into clinical practice. The tool kit is now being pilot tested with a number of practices and should be out within the year.

One participant asked Pleasant about his vision of what a comprehensive, multimethod health literacy measure looks like. What is the practicality of administering such a measure, and how could it be done? Is the comprehensive measure something just for researchers, or could this be a

population measure? Pleasant responded that it is critically important to use a consensus process to develop an agreed-on theory and framework around which measures are developed. There should be a core module of health literacy and then, depending on the context that one is addressing (e.g., chronic disease, health literacy of physicians, health literacy of patients, etc.), add-on modules would be developed. If measures for these were based on an agreed-on framework, comparisons could be made across modules and contexts. It should be possible, Pleasant continued, to develop a telephone assessment of health literacy.

The issue of measurement for research versus measurement for improvement versus measurement for what might be called accountability was raised by one participant. It is hoped that the comprehensive measure under discussion will have components that can accommodate all needs. It seems important that one identify the various needs for measurement. Pleasant responded that a number of measures, such as the REALM and the TOFHLA, are used. But questions have been raised about their validity and whether they address the scope of health literacy. The way to resolve these issues is to develop a consensus approach to the theory and framework of health literacy and then to develop a new set of measures, based on that consensus, that will fill the needs of a variety of audiences.