4

Population-Based Approaches to Assessing Health Literacy

DEMOGRAPHIC ASSESSMENT FOR HEALTH LITERACY

Amresh Hanchate, Ph.D.

Boston University School of Medicine

The approach described here is based on work described in a recent article published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine (Hanchate et al., 2008). This approach uses a different method for assessing health literacy, not in-person questions or even phone questions, but an indirect way of imputing health literacy based on patient sociodemographic indicators such as age, education, etc. Miller and colleagues (2007) proposed a similar measure based on social demographics. The main difference is that the Demographic Assessment of Health Literacy (DAHL) has been tested for external validity by applying it to population-representative samples from other surveys.

The DAHL is not used to make individual-level assessments of health literacy. Instead, it is for use in population-level analysis. The objectives of the DAHL are as follows:

-

To impute limited health literacy from sociodemographic indicators; and

-

To estimate the association of imputed limited health literacy with indicators of health status and compare findings with those from a measured indicator of limited health literacy (Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults, or S-TOFHLA).

A number of recent studies have examined the association of health literacy with poor health status, health outcomes, and health care utilization. Most of these studies have small samples, which is understandable because in-person health literacy assessment is time-consuming and costly. But the representativeness of these samples to the general population is unknown.

As has been discussed previously, health literacy is a social construct. It is intimately connected with the socioeconomic environment and with demographics. Health literacy is also complex. A few sociodemographic measures will not account for all individual differences in health literacy. For example, some people with substantial schooling may still have inadequate health literacy, and such cases will be captured only by direct measurement.

However, when one is examining population-level interrelationships such as the extent to which limited literacy is correlated with poor health status, sociodemographic factors may drive a majority of differences in health literacy. A derived measure would allow easy quantification of this relative contribution.

The potential gains of a demographic assessment could be substantial. The derived health literacy measures would be applicable to nationally representative survey data such as those obtained in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), and the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS). Using the derived measure, one could then exploit the richness of such datasets, examining the relationship of health literacy with health outcomes (especially rare events that are harder to investigate in small datasets) and with health care utilization.

Methods

Two main steps are involved in deriving the DAHL. First, one obtains the imputed measure of health literacy using a dataset that has a direct measure of health literacy, in this case the Prudential Survey data. The Prudential Survey includes an individual measure of health literacy based on the short-form TOFHLA instrument. It is one of the largest such health surveys, with a sample of about 3,000, and is representative of a number of regions around the country. The sample frame for the survey was all new enrollees to a Medicare health maintenance organization plan in four locations (Cleveland, OH; Houston, TX; South Florida; and Tampa, FL) during the 9 months from December 1996 to August 1997. The survey excluded those not living in the community, those with severe cognitive impairment, and those who were not comfortable speaking in either

English or Spanish. The effective response rate for the survey was 41 percent. Data from the Prudential Survey have been the source for a number of published studies evaluating the association between inadequate health literacy and health status.

Data from the Prudential Survey was used to estimate the linear statistical relationship between the measured S-TOFHLA health literacy score and the four selected sociodemographic indicators (age, highest educational achievement, sex, and race/ethnicity). The estimates—that is, the coefficients of the regression model—were then used as scoring weights for obtaining the imputed measure of health literacy. The Prudential data were used to evaluate the concordance between the DAHL and the S-TOFHLA.

The second step of the analyses applied the imputed scoring method to external data using two nationally representative health surveys: the 1997 NHIS and the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). The NHIS population chosen was the subset of those 65 or older, with a resulting sample of about 7,000. The HRS sample size of elderly was about 10,000. Neither of these surveys has a validated measure of health literacy.

The main analyses performed for external validation compared the association of limited health literacy with health status measures. Four health status measures were identically defined in all three surveys examined, that is, in the internal data source (Prudential) and the two external data sources (NHIS and HRS). These four measures are general health (poor or fair), hypertension, diabetes, and difficulties with activities of daily living (ADL). Logistic regressions of the health status measures were estimated as a function of the indicator of limited literacy, household income, marital status, and geographic location. This was done separately using each of the three data sources.

Results

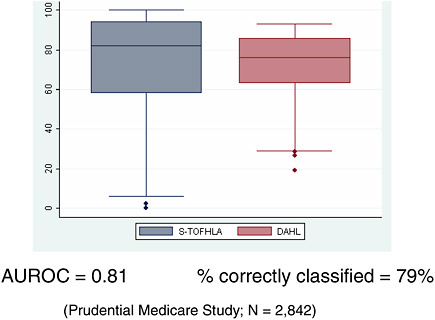

Figure 4-1 compares the distribution of the original measures of health literacy score in the Prudential Survey using the S-TOFHLA with the imputed scores of the DAHL. An important difference is that the imputed scores have a more compact distribution because the imputed scores are derived from only a few factors; the measures’ scores range from 0 to 100, but the imputed scores range from 19 to 93. A sizable portion of measured scores are above 80; nevertheless, as the imputed scores are squeezed in, the median score decreases from 83 to 76. In terms of the ability to discriminate relative differences in health literacy, the DAHL does fairly well, that is, the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC) curve is 81 percent. Typically the bottom 25 percent is classified as those

FIGURE 4-1 Results: Comparison of S-TOFHLA and DAHL scores.

SOURCE: Hanchate, 2009.

with limited literacy. If that is also done for the DAHL, then 79 percent of the observations are correctly classified into those with limited literacy and others.

Results of applying the DAHL and comparing the association of limited health literacy with health status outcomes from the NHIS can be seen in Table 4-1.

Results show that those with measured inadequate literacy using the S-TOFHLA were 77 percent more likely to report their general health to be fair or poor. If the derived indicator of inadequate literacy is used, then for the same data, the association was virtually identical. If one looked at the NHIS data and used the derived measure, the estimate was very similar.

There is concordance for hypertension, too, although of a different sort. That is, in none of the cases was the association sizable or statistically significant. For diabetes, the estimate using NHIS data was similar to that for general health. For difficulty with ADL, there is a consistently large association with inadequate literacy.

Applying the DAHL and comparing the association of limited health literacy with health status outcomes from HRS found similar results, as shown in Table 4-2.

TABLE 4-1 Association (Odds Ratio) of Inadequate Literacy with Self-Reported Health and Chronic Conditions (Comparing NHIS 1997)

|

Data Source → |

Prudential Medicare |

NHIS 1997 |

|

|

Health Literacy Measure → |

S-TOFHLA |

DAHL |

|

|

Poor/fair general health |

1.77 |

1.78 |

1.70 |

|

Hypertension |

1.08a |

1.15a |

1.07a |

|

Diabetes |

1.37 |

1.08a |

1.29 |

|

Difficulty with ADL |

1.91 |

2.57 |

2.47 |

|

aDenotes lack of statistical significance (p > 0.05). SOURCE: Hanchate, 2009. |

|||

TABLE 4-2 Association (Odds Ratio) of Inadequate Literacy with Self-Reported Health and Chronic Conditions (Comparing HRS)

|

Data Source → |

Prudential Medicare |

HRS |

|

|

Health Literacy Measure → |

S-TOFHLA |

DAHL |

|

|

Poor/fair general health |

1.77 |

1.78 |

1.92 |

|

Hypertension |

1.08a |

1.15a |

1.19 |

|

Diabetes |

1.37 |

1.08a |

1.30 |

|

Difficulty with ADL |

1.91 |

2.57 |

1.94 |

|

aDenotes lack of statistical significance (p > 0.05). SOURCE: Hanchate, 2009. |

|||

Conclusion

Results of this analysis support use of the DAHL as a proxy for identifying subgroups with limited literacy in nationally representative surveys. The four determinants of the DAHL appear to capture the important variation in health literacy as far as its impact on health status is concerned. However, it is important to remember that the DAHL is not designed for individual assessment of health literacy and it is not designed for health literacy assessment of a nonrepresentative cohort of patients.

MAPPING HEALTH LITERACY

Nicole Lurie, M.D., M.S.P.H.

The RAND Corporation

A population measure of health literacy can be developed for several reasons. Individual assessments of health literacy are time-consuming and

expensive, and they rely largely on contact with the health care system. But they are good at supporting individual-level interventions, and probably facility-level interventions. If one could conduct population-level assessment, it would be fast, it would be inexpensive, and it might begin to support population-level interventions that may conserve resources, such as pharmacy-based intervention or deployment of navigators.

A project with the National Health Plan Collaborative (a group of 12 insurers that covers about 90 million people) served as an impetus for developing a population-level assessment of health literacy. The project identified specific Census tracts in the Los Angeles area where the quality of diabetes care was particularly low, and then asked what factors might explain the pattern of performance. A major factor seemed to be that the areas with low quality of care seemed to be linguistically isolated. A number of the plans were working on health literacy, so it was decided to draw a health literacy map to compare with the map showing low quality of diabetes care.

Methods

The question then became, how would one develop a health literacy map? Several things were needed, including a population-based model and national data on health literacy. One also would need to develop a multivariable predictive model of health literacy using Census variables. One would need to apply those model coefficients to Census data. Finally, one would need to map estimates at the relevant level of aggregation.

The decision was made to develop a predictive model based on the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL). The NAAL is restricted to an English-speaking sample, and the project restricted analysis to a household sample (N = 18,541) and did not include the incarcerated population.

The NAAL uses the incomplete block-test design where each respondent answers a subset of questions. Predicted scores are based on item response theory. The NAAL tests a series of functional health literacy items (e.g., reading a prescription label, interpreting a body mass index table). Scores are on a scale of 0–500 points.

The variables in the predictive model are age, gender, education, language spoken at home, marital status, race, income, time in the United States, and metropolitan statistical area (MSA). Other than time in the United States and MSA, all of the variables were significant because they contributed to the model. Two models were constructed, one to predict mean score and one, basically, to see if one could predict the percentage or the probability of health literacy above basic level (i.e., intermediate or proficient).

The adjusted r-squared for the linear model was 0.298. Interestingly, the r-squared for education alone was only a little more than half that at 0.16. This demonstrates that the model does substantially better than any of the individual predictors alone. The predictive capacity did not vary by age group or by region of the country. Because NAAL oversampled populations in six states, the project built six predictive models with those larger populations to determine if the model performed differently on those different states. It did not.

The next issue to address was how to use Census data in the model. There are two sources of Census data. One of the sources is the 2000 Census (the census is conducted every 10 years), which aggregates data at the Census-tract level. Each Census tract has between 1,500 and 8,000 people in it. Because of the concern about information being identifiable, the Census provides only aggregated information, such as percentage of population at different ages and percentage of different races and ethnicities.

Working with 2000 data presents a problem because significant changes have occurred since the data were collected; it would be better to capture more recent data. The American Community Survey (ACS), which is a new way in which the Census is collecting data, has a rolling sample. After 5 years of data collection, the ACS will release Census-tract estimates based on the ACS. Those data should be out some time in 2009.

Results

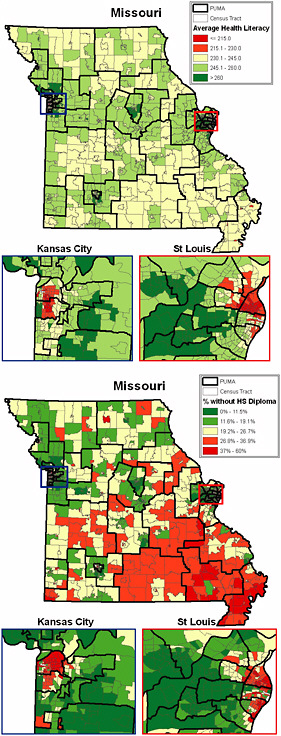

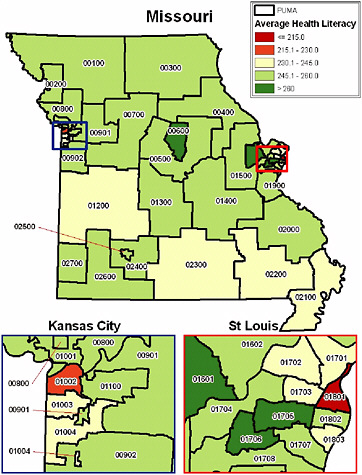

The ACS aggregates individual-level data at the Public Use Microdata Area (PUMA) level. Each PUMA has 100,000 people. Figure 4-2 is the PUMA-level map of the mean health literacy scores for Missouri. As the figure shows, certain areas of St. Louis and Kansas City have the biggest “hot spots” for low health literacy. One can also see that there are a number of other areas (in yellow) where the average health literacy score is marginal.

This kind of population-level assessment helps one think about where one might focus a health literacy intervention. These maps also can be produced for the percentage of the population with above basic health literacy.

What happens, however, if one maps education on one map and health literacy on another? The maps in Figure 4-3 use tract-level data. If one examines the map of average health literacy, one finds that there are a few pockets where average health literacy is low. But if one looks at the map of educational attainment, the percentage without a high school diploma is very low in certain parts of the state, but not all of those parts are at the worst level of health literacy.

One analysis, not reflected on these maps, showed that in the average

FIGURE 4-2 Mean health literacy by Public Use Microdata Area (PUMA) for Missouri.

SOURCE: Lurie, 2009.

Census tract in Missouri, between 25 and 40 percent of people have basic or below basic literacy. In some areas, the situation is much worse than that. This raises the following question: If one has limited resources to focus on health literacy, should one use just the level of education or just the level of income as a measure with which to target resources, or might one want to use a more precise measure?

This population-based assessment approach has limitations. First, the method has yet to be validated. How to conduct this validation is unclear because a large-scale, population-based assessment of health literacy has not been conducted using any of the other measures available. Furthermore, the validation needs to be conducted in a resource-efficient way in

different geographic areas. Another challenge is that the standard errors of tract-level estimates are larger than those of PUMAs.

Conceptually there are some important issues. One is that the optimal level of community health literacy is not known. Is there a point at which the percentage of community members with low health literacy is large enough that it has a negative effect on health outcomes? Or, conversely, is there a protective effect if a certain percentage of the community has adequate health literacy? If a community has a high percentage of individuals with low health literacy, does it risk losing those members with higher health literacy levels to other communities? Finally, whether maps of population-based assessments of health literacy will help stakeholders take action is unknown.

Conclusion

The next step probably will be to look more closely at the relationship between health literacy areas and quality of care. The idea is to identify the “hot spots” of low literacy and the hot spots of low quality to see if they relate to one another. Depending on what those maps look like, perhaps all the stakeholders—such as community organizations, philanthropy, pharmacies, and health plans—will come together to think about pilot testing some geographically focused interventions in the areas of need.

DISCUSSION

Moderator: Cindy Brach, M.P.P.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

One participant asked two questions: first, whether Lurie had the kind of data for the entire country that were available for Missouri, and second, whether those data could be correlated with the Dartmouth Atlas1 data on quality. In other words, how might the methodology she described correlate with existing measures of quality, and how might they align with geographic subdivisions?

Lurie said the goal of the project is to produce a publicly available and easily usable model with programming language that anyone could use. RAND is currently attempting to determine the costs of constructing

|

1 |

“For more than 20 years, the Dartmouth Atlas Project has documented glaring variations in how medical resources are distributed and used in the United States. The project uses Medicare data to provide comprehensive information and analysis about national, regional, and local markets, as well as individual hospitals and their affiliated physicians” (http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/). Accessed April 11, 2009. |

these maps for the country and updating the maps as the new Census data become available. The positive thing about using Census data is that one can aggregate those data to any level desired. Developing the data at a county level should be possible.

Correlating this work with the Dartmouth Atlas is a great idea, Lurie continued. What can be done is limited only by the resources available. Obtaining access to the NAAL data took 3 years, and gathering support for carrying out the project in Missouri took even longer.

Another participant addressed the theoretical frameworks for health literacy that are used to develop measures. Those frameworks treat health literacy as an individual issue when more ecological forces are at play. Perhaps the individual models should incorporate a component that addresses social capital. The participant described his grandmother as a person with an eighth-grade education and very low health literacy. She has very good health outcomes, however, in part because of her broad array of social capital supports. Incorporating social capital into the frameworks might enable one to determine whether the outcomes for those with low health literacy and high social capital are different from those with low health literacy and low social capital.

Lurie agreed and said if one looks at work in health literacy or community health education in developing countries, where large numbers of people may not be able to read, the concept of health literacy includes social networks. Hanchate added that an entire field of social epidemiology examines contextual factors.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has funded some research that demonstrates the point just made, said Cindy Brach of AHRQ. When one takes social support into account, health literacy drops in terms of its predictive abilities. The problem is that researchers have a difficult time capturing social support on large datasets for population-level measurement.

One participant who identified himself as being from Kaiser asked what some effective population management interventions might be. Lurie said the interventions she can think of may not be specific to health literacy, but would be likely to help people with low health literacy. For example, the Asheville Project2 in North Carolina paid pharmacists a bit

|

2 |

“The Asheville Project began in 1996 as an effort by the City of Asheville, North Carolina, a self-insured employer, to provide education and personal oversight for employees with chronic health problems such as diabetes, asthma, hypertension, and high cholesterol. Through the Asheville Project, employees with these conditions were provided with intensive education through the Mission-St. Joseph’s Diabetes and Health Education Center. Patients were then teamed with community pharmacists who made sure they were using their medications correctly” (http://www.aphafoundation.org/programs/Asheville_Project/). Accessed April 11, 2009. |

more to help educate people about how to take their medicines, why they are taking them, and how to be adherent. The investment resulted in a seven-to-one return in a short time period. The important thing is to think about how to focus limited resources in the most effective way.

When problems are identified in particular geographic areas, one must look carefully at what is going on in that community. For example, the National Health Plan Collaborative has data on Los Angeles, where Hispanic/Latino enrollees identified low quality of care for diabetes. The first idea for intervention was to send a letter with low-literacy levels of information in Spanish and English to thousands of members who had diabetes and Spanish surnames. But after looking at other variables, it was decided to focus the intervention on the linguistically isolated areas. In developing interventions, Lurie said, one must think much more comprehensively about the underlying drivers for health care and outcomes.

Another participant said the two presenters have both developed predictive models using demographics. Hanchate benchmarked his model to the TOFHLA, and Lurie used the NAAL. How might one decide which model would be more useful to use in certain situations? If one desires a health literacy measurement for a community, what results might be obtained using the different models? What would make one choose one model over the other?

Hanchate said the DAHL was an attempt to achieve balance between making the model as rich as possible without making it so complicated that it could not be replicated with other datasets being used for comparison.

Lurie said if one wants to look at the contribution of predictive health literacy to outcomes available in a secondary dataset, one is limited to data that exist in those datasets. The set of variables used in the RAND project is used in most datasets. The set of variables used in the DAHL is a smaller set and is available in the NHIS and others.

Dr. Angela Mickalide of the Home Safety Council said the project on health literacy mapping has implications for injury prevention as well. In Montgomery County, MD, for example, the fire department worked with literacy teachers to develop a map of literacy in the county. They overlaid that map with a map of the fire incidents, deaths, and injuries and found nearly a one-to-one perfect match, thereby identifying where efforts should be targeted. The Home Safety Council developed a home safety literacy project in which literacy teachers are provided with tools to teach students to read by using materials on fire safety, disaster preparedness, and poisoning prevention.