6

Measuring Health Literacy: What? So What? Now What?

Ruth Parker, M.D.

Emory University School of Medicine

Seven years ago the Institute of Medicine Committee on Health Literacy set out to define the scope of health literacy and to develop a set of basic indicators that could be used to assess the extent of problems in health literacy at the individual, community, and national levels. Although that committee’s report set the base for future direction, not enough was known at that time to develop measures at these various levels. Much, however, has been learned in the intervening years.

The presentations in this workshop have demonstrated that health literacy is linked to quality, to decreasing disparities, to decreasing costs; we will not make strides in any of these areas if we do not simultaneously do something about health literacy. This means that health literacy is fundamental to health reform in this country.

The definition of health literacy first proposed by Ratzan and Parker (2000) has generated much discussion, both in the literature and in this workshop. It is not perfect, but it was a start, a start at broadening the idea that communication is more than the information that is put out—it is also about what individuals take in. Health literacy reflects the dual nature of communication: what information is being disseminated and how people understand the information given to them. Looking at health literacy in this way enables a focus on making systematic improvements rather than blaming those with low health literacy skills.

Another point mentioned several times in this workshop is reflected

in the saying, “What gets measured gets done.” This is very important. To develop interventions that improve health literacy means that health literacy has to be measured. There is a developing science for health literacy, but it is not yet robust. One might think of health literacy as one thinks of medicine. Medicine may be a science, but it is practiced as an art. That is what needs to happen with health literacy. There must be a science of health literacy, but it must be artfully practiced.

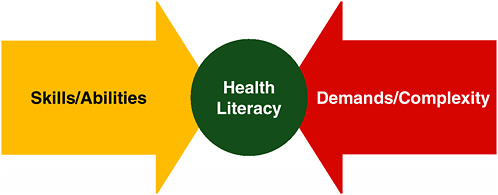

One must align skills and abilities with the demands and complexity of the system. When that is accomplished, one has health literacy (see Figure 6-1).

What is known about measures of skills and abilities? Measures of individual skills and abilities such as the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) and the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA) are used to describe prevalence and association. These measures have been around for more than 15 years. But measures at the community level, such as the geocoding measures presented earlier by Lurie, are new and exciting. Such community-based modeling allows one to take a population health approach to the measurement of skills and abilities and the development of interventions. With such measures, one can identify areas of greatest need and align resources with those needs at the population level.

Other measures are used to determine the demands and complexity of the system. More than 300 studies have documented that health material demand exceeds the ability of those who need to use the material. The new Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems

FIGURE 6-1 Health literacy framework.

SOURCE: Parker, 2009.

(CAHPS) surveys described earlier by Weidmer Ocampo will measure system demands and complexity.

But do we know what essential skills are needed, across the lifespan, to successfully navigate and engage in health? What do people need to know and understand to take care of their health? What about health systems—do health systems reflect health literacy within their organizational infrastructure? What does a literate medical home look like? Has someone defined a vision for that?

Currently we are out of alignment. The demands and complexity of the system overwhelm the skills and abilities, and health literacy, the green circle in the middle of Figure 6-1, is not as large as it should be. We should be concerned about this; balance is incredibly important.

But how can balance be achieved—how can skills and abilities match the demands and complexities? To achieve balance requires knowing the goal and figuring out how to get there. The medication label on a pill bottle provides a good example of achieving health literacy by balancing skills and abilities with demands and complexity. The National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) data provide us with information about skills and abilities, that is, about how many people can pick up a label on a pill bottle and understand what it means. Only one-third of people surveyed have the skills and abilities to read, understand, and demonstrate what is meant by a pill bottle label that says take two tablets by mouth twice a day (Davis et al., 2006). That is, only about a third could actually count out four pills. Then there is the question of when. Does twice a day mean the morning and the evening? Are 8:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. the same as morning and evening?

What about the demands and complexity of the pill bottle label? Is the pill bottle label navigable? Might there be a system change or changes that could better align the system demand and complexity with what we know about the skills and abilities? Actually a great deal of work has been done on this question. For example, the U.S. Pharmacopeia has established a task force to advance label standards, and a team of investigators is researching a new approach to labeling using a universal medication schedule developed by Alastair Wood (2007). With efforts such as these, greater balance between skills and abilities and the demands and complexities of the system is obtained, and health literacy is achieved.

What gets measured gets done. Putting health literacy on the agenda builds demand for measurement and action. Allen said earlier in her presentation, “If there are no data, there is no problem. If there is no problem, there is no action.” Health literacy measures must be implemented if there is to be balance and health literacy in the system. Health literacy must be an important agenda item within the organizational infrastructure—with assigned responsibility and funding to carry out activities.

What is needed in the field of health literacy? There is a need for a broad agreement across the field that health literacy occurs when skills and abilities are aligned with demands and complexity. Also needed are measures that reflect a dual nature—skills and abilities plus demands and complexity.

The goal is for all to be health literate. Indicators are needed that reflect progress toward the goal of aligning skills and abilities with demands and complexities. Her wish list for measures of skills and abilities, Parker said, includes the following:

-

There should be an ongoing national data repository of health literacy measures of skills and abilities within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, using what was learned from the NAAL that is housed in the Department of Education.

-

The data need to be accessible, usable, and transparent with the ability to be used in conjunction with other datasets.

-

Census tract-level data are needed so that the entire country can be mapped down to the local level. With such community mapping, one can begin to explore what is known about those communities and where resources are needed for improvement.

-

In clinical practice, one should promote “universal precautions” rather than individual skill testing. Not enough is known about individual skill testing in health literacy, so the outcomes of such testing are not ready to be placed in patients’ records and charts.

Parker also has a wish list for measures of demands and complexities. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and health plans need to develop meaningful metrics of health-literate care and service providers. Models and demonstrations are needed for what a health-literate doctor looks like, what a health-literate person in the front office is like. What do these health-literate people do when talking on the telephone with a patient, when helping people navigate the system? Incentives are also needed for the early adopters, as are prods such as standards for accreditation. Also important is that the various institutes of the National Institutes of Health and individual professional societies need to define the essential basics, the “need to know to do” for health.

Parker concluded by saying that health literacy needs to be part of Healthy People 2020. Furthermore, measures of health literacy must be linked to health quality, disparities, and costs. The report State of the USA Health Indicators (IOM, 2009) listed health literacy as an important indicator, and it is. It is a very important indicator for the country.

DISCUSSION

Moderator: George Isham, M.D., M.S.

HealthPartners

Knowledge

Brach from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) raised the point that all of the measures of individual health literacy have excluded prior knowledge and instead measure skills that are assumed to be constant. To some extent this is overwhelming in terms of measurement, trying to determine what individuals know about how their body works and other basic items.

Ratzan suggested that what might be needed are some core competencies in health literacy. What does a 4th-grader, an 11th-grader, a young adult need to know? Is there a health literacy base? Could competencies be developed for different populations?

Health Literacy in Organizations

One participant asked how health literacy can be embedded in the conceptual model for health care. Brach said that AHRQ recently published a tool kit for business strategies in chronic care. The tool kit is for physicians and practices trying to implement the chronic care model, specifically with safety net practices in mind. One of the components of the tool kit is health literacy tools.

Is health literacy an enabler, one participant asked, or is it an add-on burden or an extra cost? It would be good to start thinking about these questions. Parker said this is very important. From her perspective health literacy is not in and of itself the ultimate path to a solution for health care problems, but rather a prime layer that cuts across many areas including quality, safety, and cost. Developing measurements that allow linkage with these important variables is timely and critical.

Wilson-Stronks said that when she thinks of incorporating health literacy into organizations, she thinks of practical ways this can be done. One of these might be through the use of an advocate. Is such an approach considered when one is measuring individual health literacy? Can the individual patient be considered more broadly to include the use of advocates?

Brach responded that the individual measures considered do not take advocates into account, but that is an important point. What is needed are measures that can tell us how each person can do and what coping mechanisms they have developed, such as bringing a family member or someone else along to facilitate understanding.

Health Literacy Frameworks

Isham said the presentations and discussion at the workshop generated some thoughts about the figure Parker presented (Figure 6-1). On one side of the figure are the individual skills and abilities (the yellow arrow) that, in Parker’s presentation, reflect what the individual brings to the interaction. Although the presentation referred only to the skills and abilities of an individual patient or consumer, one might think of these individual skills as being composed of three different sets. The first set has the skills the individual patient or consumer brings to the contact with the health care system, the skills that enable activity on his or her own behalf. A second set of individual skills and abilities are those that the individual provider of care brings to the interaction at the point of contact with an individual patient. A third set of skills on this side of the figure is that of the community or population. This last set could be thought of in relation to the presentation by Lurie regarding geomapping of health literacy with other indicators.

Smith asked where the determinants of health fit in the figure presented by Parker (Figure 6-1). Parker said the model of health literacy presented in the report Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion (IOM, 2004) included social determinants. Certainly those are important and affect skills and abilities. A complete framework for viewing health literacy would necessarily have to include social determinants. Past measurement efforts have focused primarily on individual skills and abilities, Parker said. The intent of Figure 6-1 is to encourage a broader view of what needs to be measured to determine health literacy. That is, measurement of health literacy involves more than individual skills and abilities; it also must take into account the demands and complexities of the systems with which individuals must interact.

Isham said this issue had arisen earlier in conversations regarding the need for close coordination at the national level among many federal agencies. Health and health care are affected by the policies and activities of many federal agencies. For example, what the Environmental Protection Agency decides to do can have a great impact on health. Policies and activities of the Department of Education also impact health because it is known that educational attainment is a major social determinant of health. In thinking about health and health literacy, it is important to keep this overlap in mind.

The need to think beyond simple measures of health literacy, isolated from other factors, is illustrated by Lurie’s presentation, Isham said, and by the report State of the USA Health Indicators (IOM, 2009). Both of these efforts illustrate the need to pay attention to numerous factors or determinants and how they interact to produce health.

One participant said many people see health as a linear process where care is delivered to people and a health outcome is experienced. But health exists also within families and communities and is affected by socialization, by the popular culture and the media. If one is going to create an overall conceptual framework for health literacy, the participant continued, that framework should be dynamic and demonstrate how health literacy is a process created by the society and culture within which people live.

Another participant suggested that measurements for health literacy need to include collection of data that would enable research on the return on investment for the health care system and society. The information Clancy and others presented indicates that health literacy does affect health outcomes. Such effects most likely impact costs, but the relationship has not been shown. This is an important issue, especially in these times when efforts at health reform are under way.

One participant, who identified himself as working in the area of shared decision making, suggested that the newly appropriated money available for studies of comparative effectiveness should include a greater focus on the side of Figure 6-1 that lists skills and abilities. Apparently the vast majority of those dollars will be devoted to the red arrow or right side, which is the side one might call the supply side of health care services, devices, and drugs. It appears that little will be spent for research on the yellow arrow, or consumer side. There is a great deal of disequilibrium between the knowledge of the supplier and the knowledge on the demand side.

Parker agreed that supply and demand has a great deal to do with the imbalance of the system represented in Figure 6-1. There is a supply and demand problem.

International Efforts in Health Literacy

Ratzan said there is international interest in health literacy. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development is developing measures of health literacy. The United Nations is promoting health literacy, and a meeting in April in China is expected to discuss what health literacy means for the millennium development goals. How do U.S. health literacy rates compare with those in other countries? There is an opportunity to put forth a measure or some indicators that would allow the United States not only to measure progress in health literacy at home, but to measure the U.S. communities against international communities.

One participant who identified herself as being from Canada urged the group to think about the importance of measuring health literacy not

only for the United States, but for many other countries. The Canadian Center for Learning has developed numerous materials on health literacy, and a number of other countries are beginning to move into this area. Much of what has been presented could be of great value to these international efforts.