2

Adaptive Radiations: From Field to Genomic Studies

SCOTT A. HODGES and NATHAN J. DERIEG

Adaptive radiations were central to Darwin’s formation of his theory of natural selection, and today they are still the centerpiece for many studies of adaptation and speciation. Here, we review the advantages of adaptive radiations, especially recent ones, for detecting evolutionary trends and the genetic dissection of adaptive traits. We focus on Aquilegia as a primary example of these advantages and highlight progress in understanding the genetic basis of flower color. Phylogenetic analysis of Aquilegia indicates that flower color transitions proceed by changes in the types of anthocyanin pigments produced or their complete loss. Biochemical, crossing, and gene expression studies have provided a wealth of information about the genetic basis of these transitions in Aquilegia. To obtain both enzymatic and regulatory candidate genes for the entire flavonoid pathway, which produces anthocyanins, we used a combination of sequence searches of the Aquilegia Gene Index, phylogenetic analyses, and the isolation of novel sequences by using degenerate PCR and RACE. In total we identified 34 genes that are likely involved in the flavonoid pathway. A number of these genes appear to be single copy in Aquilegia and thus variation in their expression may have been key for floral color evolution. Future studies will be able to use these sequences along with next-generation sequencing

Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106.

technologies to follow expression and sequence variation at the population level. The genetic dissection of other adaptive traits in Aquilegia should also be possible soon as genomic resources such as whole-genome sequencing become available.

Adaptive radiations have played, and continue to play, a central role in the development of evolutionary theory. After his exploration of the Galápagos Islands, Darwin recognized that variants of species were confined to specific islands. In particular, Darwin (1963) noted that mockingbirds he collected on different islands represented 3 distinct forms and that all of the forms were similar to mockingbirds from the mainland of South America. He further noted that the different islands were within sight of one another, all quite similar in their habitats, and apparently geologically young. Based on these observations, Darwin (1876) began to suspect that species gradually became modified. Thus began his search for a process that could account for such observations, leading to his formulation of the theory of natural selection.

Key to Darwin’s suspicion of common ancestry was the close proximity of environmentally similar islands comprising the Galápagos archipelago. In fact, many classic examples of adaptive radiations involve islands or lakes; notable examples include Darwin’s finches of the Galápagos, honeycreeper birds and silversword plants of Hawaii, and cichlid fish of lakes Malawi and Victoria in Africa. The power of these examples for inferring the force of natural selection in evolution stems from the marked diversity in form and function among a group of clearly closely related taxa. The isolation of islands and lakes makes plausible the inference that the taxa are descended from a single ancestor, and the link between variation in form and function makes credible the notion that natural selection and evolution have played key roles.

A great deal of research effort has gone into substantiating the assumptions behind examples of adaptive radiation. In an influential book, Schluter (2000) laid out the definition of adaptive radiation as having 4 features: (i) common ancestry, (ii) a phenotype–environment correlation, (iii) trait utility, and (iv) rapid speciation. Monophyly and rapid speciation for many of the classic examples of adaptive radiation have been established by using molecular techniques [e.g., cichlids (Meyer et al., 1990), Galápagos finches (Petren et al., 1999; Sato et al., 1999), and Hawaiian silverswords (Baldwin and Sanderson, 1998)]. Ecological and manipulative experiments are used to identify and test phenotype–environmental correlations and trait utility. Ultimately, such studies have pointed to the link between divergent natural selection and reproductive isolation and, thus, speciation (Schluter, 2000).

Studies of adaptive radiations have exploded during the last 20 years. In a search of the ISI Web of Science with “adaptive radiation” (limited to the subject area of evolutionary biology) we found 80 articles published in 2008 compared with only 1 in 1990. Furthermore, citations of these articles have grown exponentially, from 34 citations in 1990 to >3,000 in 2008. The growing interest in adaptive radiations may be ascribed to several factors. First, molecular phylogenetics has allowed the identification of monophyly and rapid speciation in taxa outside of the traditionally recognized examples from isolated islands and lakes [e.g., Hodges and Arnold (1994)] and thus has expanded the repertoire of study systems. Second, there has been a resurgence in the study of speciation (Coyne and Orr, 2004). Speciation research has often focused on the development of genetic incompatibilities [e.g., Mihola et al. (2009) and Phadnis and Orr (2009)], whereas studies of adaptive radiations have focused attention on the role of divergent natural selection to alternate environments as a primary cause of reproductive isolation (Schluter, 1996, 2000, 2001; Rundle et al., 2000; Via, 2001). Thus, studies of adaptive radiations focus on both the evolution of adaptations and reproductive isolation.

Understanding the processes of adaptation and speciation requires considering taxa that have not yet fully attained reproductive isolation. Fundamentally, the ability to make hybrids allows the dissection of the genetic basis of traits and permits tests of how individual genetic elements could affect individual fitness. For example, Bradshaw and Schemske (2003) made near-isogenic lines of Mimulus cardinalis and Mimulus lewisii, each containing the alternate allele from the other species for a flower color locus. They found that pollinator visitation patterns radically changed and that, in the proper ecological setting, an adaptive shift in pollinator preference could possibly occur with a single mutation (Bradshaw and Schemske, 2003). In addition, studying speciation and adaptation early in the process has significant advantages because subsequent genetic changes can obscure the actual causal mutations [Via and West (2008); see also Via, Chapter 1, this volume]. For example, loss-of-function mutations that confer an adaptive advantage may be followed by additional mutations that would, on their own, cause loss of function but were not involved with the evolution of the trait itself (Zufall and Rausher, 2004). Thus, recent adaptive radiations are especially fruitful resources for dissecting the genetic basis of adaptations and speciation.

Adaptive radiations have also played a major role in identifying evolutionary trends. This area of study is important because trends imply predictable patterns in evolutionary history. There has been, for example, much debate about whether body size and complexity increase through time (Damuth, 1993; Jablonski, 1997; Hibbett and Binder, 2002; Hibbett, 2004; Van Valkenburgh et al., 2004). One way to test for repeatable trends

has been to test whether the evolution of particular traits is associated with species diversity. For example, clades of flowering plants that have independently evolved floral nectar spurs show a statistically significant trend for increased species diversity compared with nonspurred clades (Hodges and Arnold, 1995; Hodges, 1997; Kay et al., 2006). This finding has led to the nectar spurs being considered a “key innovation” with the implication that they mechanistically increase the likelihood of speciation.

Another way to test for trends during evolutionary history is to test explicitly for directionality of trait evolution on a phylogeny. Critical to such analyses is the reconstruction of ancestral states (Schluter et al., 1997; Mooers and Schluter, 1999). Here, maximum-likelihood methods have been used to statistically distinguish between a 1-rate model (in which both directions of evolution have the same rate) and a 2-rate model (Pagel et al., 2004). However, the ability to test between such models depends on the number of shifts observed (Mooers and Schluter, 1999). Because adaptive radiations often are composed of a large number of species and have entailed multiple shifts in characters, they are prime foci for tests of directional trends [e.g., Mooers and Schluter (1999)].

As the development, use, and availability of genomic tools for non-model organisms has increased (Abzhanov et al., 2008), the ability to determine the genetic basis of adaptations and speciation is becoming possible for an increasing number of taxa. Long-standing questions about whether particular kinds of genes [e.g., regulatory versus structural; see Britten and Davidson (1969), King and Wilson (1975), Barrier et al. (2001), Hoekstra and Coyne (2007)] and/or particular types of mutations such as substitutions, duplications, or transposable elements are responsible for adaptation and speciation can now be addressed. Adaptive radiations are especially amenable to such studies for a number of reasons. First, because adaptive radiations have been studied for some time, particular trait values have often been substantiated as adaptations. Second, recent adaptive radiations often consist of taxa that can be hybridized, thus making possible the genetic dissection of traits. Third, adaptive radiations may entail a diversity of adaptive traits or the repeated evolution of the same traits in different lineages providing multiple comparisons within and between traits in a single system. Finally, because recent and rapid adaptive radiations necessarily consist of closely related taxa, the development of genomic tools for 1 species will likely provide tools for analysis across the entire group (Abzhanov et al., 2008). Thus, adaptive radiations offer the possibility of determining general molecular trends across traits and whether convergence at the phenotypic level involves convergence at the molecular level.

Here, we illustrate the use of adaptive radiations to understand the processes of adaptation and speciation by reviewing studies of the col-

umbine genus, Aquilegia. We first outline the broad evolutionary trends pointing to specific traits as being important in this adaptive radiation and briefly review the studies explicitly testing the function of these traits. We then highlight how genomic studies are aiding in our understanding of the genetic basis of adaptation and speciation, emphasizing flower color as a primary model. We end with a look toward how the genetic dissection of more complex traits will be possible in the near future.

EVOLUTIONARY TRENDS IN AQUILEGIA

In a classic prediction of an evolutionary trend, Darwin (1862) hypothesized that the spurs of flowers and the tongues of pollinators could undergo a coevolutionary “race” and become increasingly long. However, an alternative hypothesis posited that spurs evolve to fit the already-established tongue length of pollinators, and that spur length increases only when a shift to a new and longer-tongued pollinator occurs (Wallace, 1867; Wasserthal, 1997). This second hypothesis also predicts a directional evolutionary trend: shifts to shorter spurs may be less likely because shorter-tongued pollinators will avoid visiting flowers whose nectar reward they cannot reach. Recently these alternative hypotheses were explicitly tested with a species-level phylogeny of the North American adaptive radiation of Aquilegia (Whittall and Hodges, 2007). Transitions between major classes of pollinators were found to be significantly directional, consisting of bee to hummingbird and hummingbird to hawkmoth but no reversals and no bee to hawkmoth transitions. Concomitant with these shifts were increases in spur length. In addition, models of the tempo of evolution strongly indicated the concentration of spur-length evolution at times of speciation. Thus, as with the broad correlation between the evolution of spurs themselves and species diversity, this study suggests that spur length is intimately linked with the speciation process, at least in North American species of Aquilegia (Whittall and Hodges, 2007; Hodges and Whittall, 2008). Functionally, matching of spur length to tongue length has been shown to be adaptive because Aquilegia flowers with artificially shortened spurs have less pollen removed from their anthers, and presumably deposited on their stigmas, because of the body of the pollinator being held further away from the flower (Fulton and Hodges, 1999).

The pollinator shifts found in Aquilegia entail transitions in other traits besides spur length. The orientation of flowers at anthesis can be either pendent or upright (Hodges et al., 2002). All hummingbird-pollinated species of Aquilegia have pendent flowers, which is common in other hummingbird-pollinated species as well (Cronk and Ojeda, 2008). All 5 inferred shifts from hummingbird to hawkmoth pollination entail a transition from fully pendent flowers to upright flowers. This shift is adaptive,

because experimental manipulation of upright Aquilegia pubescens flowers to the pendent orientation reduced hawkmoth visitation by an order of magnitude (Fulton and Hodges, 1999). One bee-pollinated species, Aquilegia jonesii, has upright flowers; however, the entire plant is only 2–10 cm tall and the flowers are held just above the foliage (Munz, 1946). Given these constraints, upright flowers offer the best access to the spurs and pollen by bee pollinators.

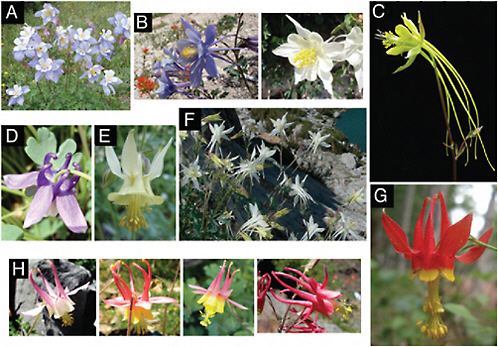

Perhaps one of the most visually striking features of the North American adaptive radiation of Aquilegia is the diversity of floral color, resulting from multiple, independent shifts (Figs. 2.1 and 2.2). Using the same Aquilegia phylogeny as for pollinator transitions, Whittall et al. (2006b) reconstructed the ancestral states for the presence (blue or red) or absence (yellow or white) of floral anthocyanins and inferred a significant trend of 7 independent losses and no gains (Fig. 2.2). These shifts in color appear to be largely adaptive because all 5 inferred shifts to hawkmoth pollination are coincident with loss of anthocyanin production (Whittall et al.,

FIGURE 2.1 Photographs of Aquilegia flowers. (A) A. coerulea (blue/white). (B) A. scopulorum, which can be polymorphic for blue (Left) and white (Right) flowers. (C) A. longissima (yellow). (D). A. saximontana (purple). (E) A. flavescens (yellow). (F) A. pubescens (white). (G) A. formosa (red/yellow). (H) Natural hybrids between A. formosa and A. pubescens. Photos by N. Derieg (A, B, D, E, and G) and S. Hodges (C, F, and H).

![FIGURE 2.2 Phylogeny of the North American species of Aquilegia [see Whittall and Hodges (2007)]. Shading at the branch tips indicates flower color: black indicates blue; gray indicates red; and open indicates white or yellow. Taxa may be fixed for a flower color (whole circles at branch tips) or polymorphic (half circles at branch tips). Shading (as above) at nodes indicates the most parsimonious reconstruction of color, with the likelihood of producing anthocyanins indicated by shaded pie diagrams. To the right of taxon names are 3 boxes indicating, from left to right, the absence (open symbols) or production of delphinidins (black filled), cyanidins (hatched), and pelargonidins (gray) based on Taylor (1984). Arrows indicate down-regulation of genes late in the core anthocyanin pathway in flowers of that species compared with the regulation in the anthocyanin-producing species A. formosa, A canadensis, and A. coerulea (Whittall et al., 2006b). Lines on the right indicate species that form natural hybrids.](/openbook/12692/xhtml/images/p20019ad4g33001.jpg)

FIGURE 2.2 Phylogeny of the North American species of Aquilegia [see Whittall and Hodges (2007)]. Shading at the branch tips indicates flower color: black indicates blue; gray indicates red; and open indicates white or yellow. Taxa may be fixed for a flower color (whole circles at branch tips) or polymorphic (half circles at branch tips). Shading (as above) at nodes indicates the most parsimonious reconstruction of color, with the likelihood of producing anthocyanins indicated by shaded pie diagrams. To the right of taxon names are 3 boxes indicating, from left to right, the absence (open symbols) or production of delphinidins (black filled), cyanidins (hatched), and pelargonidins (gray) based on Taylor (1984). Arrows indicate down-regulation of genes late in the core anthocyanin pathway in flowers of that species compared with the regulation in the anthocyanin-producing species A. formosa, A canadensis, and A. coerulea (Whittall et al., 2006b). Lines on the right indicate species that form natural hybrids.

2006b), pale flowers set more seed when hawkmoths are present (Miller, 1981), and in manipulative studies hawkmoths preferentially visit pale flowers (Hodges et al., 2002). To consider trends in color shifts when anthocyanin production is maintained, we inferred the color produced at ancestral nodes in the Aquilegia phylogeny by using the inferred pollination syndrome as a guide (Whittall and Hodges, 2007). Given that hummingbird-pollinated flowers in general tend to be red (Cronk and Ojeda, 2008) and all but 1 hummingbird-pollinated species of Aquilegia have red flowers (Aquilegia flavescens has yellow flowers), we inferred ancestral nodes reconstructed as hummingbird-pollinated anthocyanin producers to be red-flowered (Fig. 2.2). Similarly, given that bee-pollinated flowers tend to be blue and all but 1 bee-pollinated species of Aquilegia have blue flowers (Aquilegia laramiensis has white flowers) we inferred ancestral nodes reconstructed as bee-pollinated anthocyanin producers to be blue-flowered (Fig. 2.2). These reconstructions suggest that there have been 2 shifts from blue to red flowers and 2 shifts from red to blue. Thus, color shifts in Aquilegia, where anthocyanin production is maintained, do not exhibit an evolutionary trend.

FLOWER COLOR AND THE GENETICS OF ADAPTATION

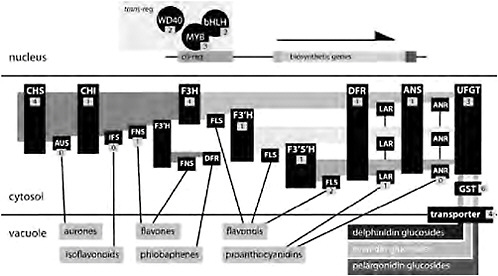

The significant trends in pollinator evolution in Aquilegia, together with field experimentation on the functional relevance of specific traits, make variation in spur length, flower orientation, and flower color obvious targets for understanding the genetic basis of adaptive traits and traits affecting reproductive isolation. However, focusing on the genetics of flower color evolution is also advantageous for practical reasons. Since Mendel’s first experiments, flower color has been a primary system for dissecting the genetics of a biochemical pathway because the phenotype is readily observable and relatively simple. Many genes in the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway (ABP) and their regulators have been described, thus facilitating efforts to identify the likely targets of selection. Reds and blues of most flowers result from the accumulation of anthocyanin pigments in the vacuoles of floral tissue cells (Fig. 2.1A, D, and G). When anthocyanins are absent, flowers are yellow or white, largely depending on, respectively, the presence or absence of carotenoid pigments (Fig. 2.1C and E). Anthocyanin biosynthetic genes are a central core to the larger flavonoid biosynthetic pathway and are expressed in multiple tissues other than flowers (Grotewold, 2006). The production of all anthocyanins involves 6 enzymes [in functional order chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone flavone isomerase (CHI), flavanone-3-hydroxylase (F3H), dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR), anthocyanidin synthase (ANS), and UDP flavonoid glucosyltransferse (UFGT); Fig. 2.3]. There are 3 basic types of anthocya-

FIGURE 2.3 A generalized flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. In the nucleus, 3 transregulators (a WD40, a bHLH, and a Myb) coordinately affect the expression of multiple genes of the core pathway by binding to their cis-regulatory elements. Enzymes are indicated in the cytosol with black boxes, and the number of candidate genes identified in Aquilegia is indicated. Biochemical intermediates are indicated with light shading in the cytosol, with the substrate for each enzyme to the left and the product to the right. Specific anthocyanins (indicated by darker shading in the vacuole) are glucosides of pelargonidins, cyanidins, and delphinidins. Lines from enzymes to their products in the vacuole indicate side-branch pathways. Enzymes are: CHS, CHI, UFGT, anthocyanin GST (GST), F3′H, F3′5′H, aurone synthase (AUS), isoflavone synthase (IFS), flavone synthase (FNS), FLS, leucoanthocyanidin reductase (LAR), and ANR.

nins: pelargonidins (orange/red), cyanindins (blue/magenta/red), and delphinidins (blue/purple). The production of pelargonidins requires just the core enzymes, but the production of cyanidins and delphinidins depends on 2 enzymes [flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase (F3′H) and flavonoid 3′5′-hydroxylase (F3′5′H)] that add 1 or 2 hydroxyl groups, respectively, on the β-ring of the product of F3H (Grotewold, 2006; Rausher, 2008). Subsequently, DFR, ANS, and UFGT act to produce anthocyanins, which are then transported into the vacuole where they accumulate and produce visual colors (Fig. 2.3).

Rausher (2008) has described general trends in flower color evolution: shifts are generally blue to red or from producing anthocyanin to not, although exceptions do occur. Considering the biochemical pathway for anthocyanins, Rausher pointed out that these trends likely arise because mutations causing loss of function are more likely than those causing

gain of function. Loss of function of any enzyme in the core ABP would cause a loss of anthocyanin production and loss of function of F3′H or F3′5′H would cause a shift from blue to red. Transitions in the opposite directions would necessitate the gain of enzymatic function. Furthermore, after a loss-of-function transition, additional loss-of-function mutations may accumulate, making reversals even less likely (Zufall and Rausher, 2004). In the case of blue to red shifts, substrate specificity for the product of F3H may evolve, making reversals less likely as well (Zufall and Rausher, 2003).

Changes in flower color could also occur because of altered metabolic flux in side branches of the flavonoid pathway. At each of the intermediate steps in the ABP, side branches lead to the production of other important compounds such as flavones, flavonols, and proanthocyanidins (tannins) (Fig. 2.3). In fact, the entire flavonoid pathway is likely to be more complicated than that depicted in Fig. 2.3. For instance, in Arabidopsis recent profiling of both flavonoid production and gene expression in flavonoid mutants resulted in the identification of 15 new compounds and the functional characterization of 2 new genes in the pathway (Yonekura-Sakakibara et al., 2008). Changes in the abundance or activity of side-branch enzymes could result in flux away from or toward anthocyanin production and affect changes in flower color. For instance, deep-pink flowers of Nicotiana tobacum can be converted to white by overexpressing a side-branch enzyme [anthocyanidin reductase (ANR)] (Xie et al., 2003). Similarly, conversion of white flowers to those producing anthocyanins has been achieved in Petunia by silencing the side-branch enzyme flavonol synthase (FLS) and activating DFR (Davies et al., 2003). Given that the side-branch pathways result in compounds that are important for a number of other plant functions such as UV protection and herbivore resistance (Winkel-Shirley, 2002; Treutter, 2006), selection for these compounds could result in pleiotropic changes in flower color (Strauss and Whittall, 2006). However, changes in flower color caused by altered biosynthetic flux requires increases in expression levels or enzyme activity and are thus gain-of-function mutations, which, although certainly possible, are likely rarer than loss-of-function mutations (Orr, 2005).

A few studies have begun to determine the genetic basis of natural flower color variation. In Petunia axillaris, white flowers can be made pink by the introduction, either through introgression or transgenetics, of a functional copy of AN2, the R2R3-myb transcription factor that controls expression of genes late in the core ABP (Fig. 2.3). Sequence analysis of AN2 alleles from a range of collections indicated 5 independent loss-of-function mutations, suggesting that loss of color arose multiple times (Hoballah et al., 2007). However, most of these alleles also displayed strong down-regulation and thus it is possible that the loss-of-function

alleles arose subsequent to the down-regulation of AN2 expression. In Mimulus aurantiacus, segregation analysis of an F2 population for both color and sequence variants of the core ABP genes, along with analysis of their expression and functional capabilities, indicated that a locus acting in trans accounts for 45% of color variation (Streisfeld and Rausher, 2009). These 2 studies provide the strongest evidence that changes in trans-regulators are responsible for shifts involving changes in the production of anthocyanins as a whole. Shifts from blue to red flowers have been studied in Ipomoea (Zufall and Rausher, 2004). Two mutations, 1 causing a loss of F3′H expression and 1 causing a change in the specificity of DFR for the substrate produced by F3′H rather than that produced by F3′H, are sufficient for this color transition. However, which of these mutations occurred first and thus produced the initial color shift is unclear. In these examples, the primary focus has been on the core ABP genes and their regulators. We know of no study that also has considered how changes in flux from side branches of the core ABP may have affected anthocyanin production in natural systems.

AQUILEGIA AS A MODEL FOR STUDYING FLORAL COLOR EVOLUTION

Aquilegia has been used for nearly 50 years to study the evolution and genetics of flower color. Prazmo (1961, 1965) made extensive crossing studies among purple-, white-, red-, and yellow-flowered species of Aquilegia and followed segregation ratios in F2, F3, and backcross populations. She found that flower color variation could largely be ascribed to 4 independently assorting factors (Prazmo, 1965): Y, which regulates the existence of yellow chromoplasts; C and R, which are needed for the formation of anthocyanins; and F, which modifies red anthocyanins into bluish-violet pigments. In crosses between either Aquilegia chrysantha or Aquilegia longissima (both of which lack floral anthocyanins) and species with floral anthocyanins, Prazmo (1961, 1965) found that a single gene (R) could account for anthocyanin production. Whittall et al. (2006b) found that multiple genes late in the core anthocyanin pathway, especially DFR and ANS, were down-regulated in A. chrysantha, A. longissima, and Aquilegia pinetorum, which together form a clade of taxa lacking floral anthocyanins (Fig. 2.2). These results suggest that Prazmo’s factor R is a transregulator of genes late in the ABP. In crosses with the white form of Aquilegia flabellata, Prazmo also found that a second gene (C) could account for anthocyanin production. Whittall et al. (2006b) found that only CHS was down-regulated in white A. flabellata. Thus, Prazmo’s factor C is likely a mutation in either a transregulator or the cis-regulatory region of CHS. Significantly, F1 progeny from crosses between white A. flabellata and

yellow A. longissima or A. chrysantha produce anthocyanins, confirming independent mutations blocking anthocyanin production (Prazmo, 1965; Taylor, 1984). Finally, Prazmo’s factor F is a mutation that most likely affects either the expression or the function of F3′5′H (Fig. 2.3), because blue/purple-flowered species of Aquilegia primarily produce delphinidins [Fig. 2.2; Taylor (1984)].

Biochemical analyses of anthocyanins found in Aquilegia species have also been conducted (Taylor and Campbell, 1969; Taylor, 1984; Whittall et al., 2006b). These studies suggest that losses of floral anthocyanins are likely caused by changes in expression patterns of the core enzymatic genes of the ABP or changes causing substrate flux away from anthocyanin production. In an extensive analysis of flavonoids and other phenolic compounds, Taylor and Campbell (1969) found that species that lack floral anthocyanins (A. pubescens, A. longissima, A. flavescens) all produce anthocyanins in other tissues. Thus, genes in the ABP must be functional and, if expressed, would result in flowers with anthocyanins. Similarly, Whittall et al. (2006b) found that both flavones and flavonols are produced in the flowers of species that lack anthocyanins, confirming that the genes expressed early in the ABP are functional.

In an analysis of floral anthocyanins, Taylor (1984) found that species with blue/purple flowers produced either just delphinidins or a combination of delphinidins and cyanidins, whereas red-flowered species produced both cyanidins and pelargonidins. From North America, he included 2 red-flowered species (Aquilegia formosa and Aquilegia canadensis) and 2 blue-flowered species (Aquilegia brevistyla and Aquilegia coerulea). According to our reconstruction of ancestral flower colors (Fig. 2.2), these species represent the descendants of 1 shift from blue to red (A. canadensis from the common ancestor with A. brevistyla) and 1 shift from red to blue (the A. coerulea clade from the common ancestor with the A. formosa clade). The first case likely resulted from loss of function or down-regulation of F3′5′H and a concomitant increase in flux down the cyanidin and pelargonidin portions of the ABP. This finding suggests that DFR in the ancestor of A. canadensis was a substrate generalist, unlike some taxa (e.g., Nicotiana) where DFR is specialized for the products of F3′H and F3′5′H and cannot act on the product of F3′H to produce red pelargonidins (Nakatsuka et al., 2007). The second case appears to be an example of a reversal, with the recovery of F3′5′H activity and delphinidin production. Interestingly, F3′5′H is likely expressed and functional in rare individuals of A. pubescens with blue-lavender flowers (Chase and Raven, 1975), suggesting that a functional copy of this gene has been maintained in this species as well.

IDENTIFYING CANDIDATE GENES FOR THE FLAVONOID PATHWAY IN AQUILEGIA

As we have illustrated, a variety of genes could be involved with evolutionary shifts in flower color in Aquilegia. Flower color could be affected by the enzymatic function/activity of genes in either the core or side branches of the flavonoid biochemical pathway or by mutations affecting gene expression either through cis or trans regulation. Multiple copies of genes could also be involved. Although some researchers have predicted that changes are more likely to occur at transregulators (Clegg and Durbin, 2000; Whittall et al., 2006a), because this would allow the structural genes to be used in other tissues, no study to date has considered the expression and function of the entire flavonoid pathway (Fig. 2.3). To initiate such a study, we sought to identify candidate genes for the flavonoid pathway in Aquilegia. Using genes of known function (primarily from Arabidopsis) we conducted tblastn searches of the Aquilegia gene index (http://compbio.dfci.harvard.edu/tgi/cgi-bin/tgi/gimain.pl?gudb=aquilegia). This database is derived from EST sequencing from a broad range of tissues and developmental stages of greenhouse hybrids between A. formosa and A. pubescens, including floral tissue producing anthocyanins. The current gene index contains 13,556 tentative consensus (TC) sequences and 7,278 singleton ESTs and, thus, likely represents a large fraction of the expressed genes in Aquilegia. From these initial searches, we used the strongest Aquilegia hits in tblastx searches of The Arabidopsis Information Resource and National Center for Biotechnology Information, and those that resulted in best hits to the original characterized gene were retained as potential flavonoid pathway genes.

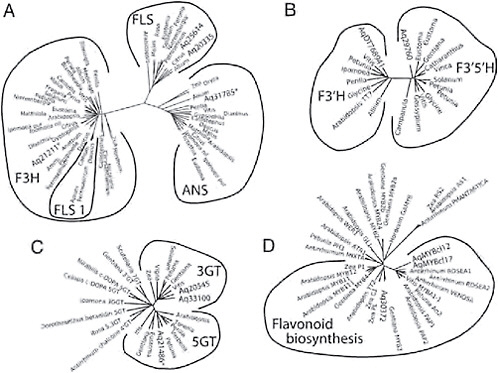

Several genes in the flavonoid pathway belong to large multigene families, making the criterion of reciprocal best hit for identifying homologous genes suspect. However, phylogenetic analysis of a number of these multigene families has identified clades that contain proteins with common function (Gebhardt et al., 2005; Bogs et al., 2006; Nakatsuka et al., 2008b). Thus, after we identified candidates for these genes through tblastx searches, we then included their inferred protein sequences in ClustalW alignments of genes from these studies and conducted neighbor-joining analysis. We then assigned genes to functional groups based on their phylogenetic clustering. For instance, F3H, FLS, and ANS all belong to a large gene family of 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases (2-ODDs). However, across multiple species, genes with the same enzymatic function form monophyletic clades in phylogenetic analyses of 2-ODDs (Gebhardt et al., 2005) (Fig. 2.4A). Inclusion of Aquilegia sequences in the alignment of 2-ODDs resulted in a tree with 1 Aquilegia sequence in each of the F3H and ANS clades and 2 sequences in the FLS clade (Fig. 2.4A). We used a similar approach to identify F3′H and F3′5′H homologs using the

FIGURE 2.4 Gene trees of loci with known function and candidate loci for similar function from Aquilegia. (A) Flavonoid 2-ODDs, including F3H, FLS 1, FLS, and ANS. (B) Flavonoid hydroxylases (F3′H and F3′5′H). (C) Glycosyltransferases (3GT, 5GT, and various others). (D) Myb transcription factors (Mybs affecting the regulation of genes in the flavonoid pathway). Within each tree, the outer lines indicate groups of genes that carry out the same enzymatic function. Aquilegia sequences are indicated by Aq followed by the TC number from the Aquilegia Gene Index or AqMYBcl12 and AqMYBcl17.

sequences from Bogs et al. (2006) and those from Nakatsuka et al. (2008b) to identify homologs of UF3GT and UF5GT (Fig. 2.4B and C). Support for the identification of UF3GT and UF5GT homologs in Aquilegia but not one for UF7GT is the fact that Taylor (1984) found only 3- and 5-glucosides and 3,5-diglucoside classes of anthocyanins in Aquilegia.

Using the Aquilegia gene index we identified candidates for nearly all major genes in the flavonoid pathway (Table 2.1 and Fig. 2.4A–C). However, 1 key gene, the R2R3-myb transcription factor that controls the expression of multiple genes in the ABP in other systems (Hoballah et al., 2007), appeared to be absent from the gene index. When we searched the index with AN2, the myb transcription factor that controls anthocyanin production in Petunia flowers (Hoballah et al., 2007), the best hit, TC30372,

TABLE 2.1 Candidate Genes from Aquilegia for the Flavonoid Pathway and Its Regulation

did not result in a reciprocal best hit to any known myb transcription factor controlling flower color. Given that changes in expression are likely causes of many of the shifts in flower color in Aquilegia, identifying the transregulators of the pathway is particularly important. Using RT-PCR and 3′ and 5′ RACE we identified 2 novel myb sequences, AqMyb12 and AqMyb17 (GenBank accession nos. FJ908090 and FJ908091) expressed in sepals of A. formosa. After alignment with the inferred amino acid sequences of other myb proteins (Nakatsuka et al., 2008a) we found that AqMyb12 and AqMyb17 clustered with other known regulators of floral anthocyanins (e.g., Antirrhinum ROSEA1, ROSEA2, and VENOSA and Petunia AN2; Fig. 2.4D) suggesting that these 2 genes are strong candidates as key regulators of the ABP in Aquilegia.

Our analysis revealed 27 candidates for enzymatic genes in the flavonoid pathway and 7 candidates for transcription factors regulating the core anthocyanin pathway. Interestingly, 4 genes of the core ABP (CHI, F3H, DFR, and ANS) appear to exist as single copies. Loss of enzymatic function of any of these genes would cause the loss of anthocyanin production. However, if these genes are truly single copy then such mutations would also eliminate the products of the side-branch pathways dependent on each enzyme and these losses would occur in all tissues (Fig. 2.3). These potentially detrimental pleiotropic effects likely favor mutations that only change the expression of these genes in floral tissues. In fact, down-regulation of DFR and ANS has been correlated with loss of anthocyanin production in most white/yellow-flowered species of Aquilegia, suggesting that mutations in a common transregulator are responsible for these color shifts (Whittall et al., 2006b). Loss of expression of these 2 enzymes would enable the continued production of most other products of the flavonoid pathway such as flavones and flavonols in floral tissue and may be particularly favored (Whittall et al., 2006b). We also found single copies of F3′H and F3′5′H and thus changes in expression patterns of these genes is most likely responsible for shifts between blue and red flowers. As described above, loss of enzymatic function in these genes in red-flowered species would make future transitions to blue flowers especially unlikely. Because red to blue transitions have apparently occurred in Aquilegia (Fig. 2.2) we would predict that F3′H and F3′5′H have likely retained enzymatic function but lost expression in red-flowered Aquilegia species.

MOLECULAR DISSECTION OF FLOWER COLOR VARIATION IN AQUILEGIA

In addition to identified candidates for nearly all major genes in the flavonoid pathway, 2 features of Aquilegia make it a particularly powerful system for identifying the molecular basis of flower color evolution. First

is the ability to cross virtually any 2 species (Prazmo, 1965; Taylor, 1967). Segregating populations allows for quantitative trait loci (QTL) analysis and the subsequent ability to identify whether genes in the ABP cosegregate with QTL. In an initial analysis of flower color in A. formosa and A. pubescens a single QTL was identified (Hodges et al., 2002) and it should now be possible to determine which, if any, of the genes in the flavonoid pathway cosegregate with flower color. The ability to cross species also allows introgression and the creation of near-isogenic lines as described above. Second is the high degree of sequence similarity among species of Aquilegia (Whittall et al., 2006a), which makes molecular resources developed in 1 species very likely to be transferable to others. For example, a reverse genetic approach, virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS), was developed in A. vulgaris, a European species, but using sequence information of ANS from North American species (A. formosa and A. pubescens) (Gould and Kramer, 2007). Silencing the ANS gene in A. vulgaris converted the normally deep-purple flowers to white (Gould and Kramer, 2007), confirming that a single copy of ANS is expressed in floral tissue. Furthermore, the VIGS technique itself is applicable across species of Aquilegia (Gould and Kramer, 2007).

Natural populations of Aquilegia that vary in flower color also will offer distinct advantages for uncovering the genetic basis of flower color. The production of controlled crosses in the laboratory can be labor intensive and does not necessarily break up genes linked even at relatively great physical distances. Thus, a single QTL may harbor many genes that could potentially affect the trait of interest. For instance, we have identified 34 genes that may play a role in the core ABP and its side-branch pathways (Table 2.1), thus implicating an average of nearly 5 such genes per chromosome (there are 7 pairs of chromosomes in Aquilegia). Of course, there may be even more genes involved in the flavonoid pathway as the Aquilegia gene index likely does not contain all paralogs of the ABP genes and additional side-branch enzymes are possible (Yonekura-Sakakibara et al., 2008). Thus, it is likely that any 1 QTL region may harbor multiple genes in the ABP. However, natural populations polymorphic for flower color are likely to have had long histories of recombination and low linkage disequilibria. In such populations, it should be possible to follow sequence variation at all of the genes in the ABP and identify specific genes that correlate with (and actually influence) flower color.

Aquilegia offers many examples of pronounced variation in flower color. For example, populations of A. coerulea (Miller, 1978, 1981) and Aquilegia scopulorum are often polymorphic for this trait (Fig. 2.1B). In addition, many natural hybrids exist between several Aquilegia species. Hybrid populations of A. formosa (red; Fig. 2.1G) and A. pubescens (primarily white; Fig. 2.1F) have been studied for many years and produce a broad range of

floral phenotypes (Fig. 2.1H). In addition, we have identified numerous hybrid populations between taxa with different flower colors (Fig. 2.2). All such populations offer research opportunities to increase the precision of genotype/phenotype correlations, and perhaps even allow definitive verification of specific genes underlying color variation in Aquilegia.

THE FUTURE OF GENETIC ANALYSIS OF ADAPTATIONS

Despite identification of the likely players in flavonoid pathway function and evolution in Aquilegia (Table 2.1), following the expression and sequence variation in all of these genes in natural or laboratory populations is daunting. With advances in DNA sequencing, such analyses may nonetheless soon become possible in Aquilegia and other natural systems. First, genome sequencing provides a scaffold for mapping variation and identifying the candidate genes that underlie QTL. The Aquilegia genome is currently in production for 8× sequencing (at the Joint Genome Institute), and as sequencing costs decline, similar genomic resources should become available for many additional natural systems. Second, next-generation sequencing techniques open the prospects for sequencing whole transcriptomes from population samples (Kahvejian et al., 2008; Shendure and Ji, 2008). As we have shown here, even without a whole-genome sequence, characterization of ESTs can provide the necessary scaffolds for analyzing the short reads these technologies produce. Thus, if such population-level analysis becomes a reality, then it will be possible to quickly obtain both expression and sequence data for genes underlying flower color (Gilad et al., 2008) in a large number of populations.

Genomic resources will also greatly aid in our ability to dissect traits about which we currently understand little in terms of underlying biochemistry and genetics. Although traits such as petal spur length and flower orientation have strong effects on pollinator visitation and resulting pollen transfer (Hodges et al., 2004), our knowledge of how these traits are genetically influenced and biochemically expressed is meager. Genes affecting cell size or cell number may cause spur-length differences between species. Variation in flower orientation among species is the result of heterochrony as all flowers of Aquilegia go through a similar pattern of orientation during development (Hodges et al., 2002). Early developmental stages of buds are upright; they then become pendent and ultimately become upright again. Differences between species arise because of differences when anthesis occurs in this sequence (Hodges et al., 2002). Little is known about the types of genes that may affect such floral differences and thus the genetic dissection of these traits is more challenging. However, as noted above, the existence of hybrid zones between species that differ in these traits offers the possibility that genomic techniques, such as

association mapping, will allow the identification of the genes underlying traits such as these.

CONCLUSIONS

Adaptive radiations continue to offer a rich resource for understanding the process of evolution. As we have outlined here, they are ideal for identifying general evolutionary trends and often consist of the repeated evolution of the same traits, allowing tests of whether evolution follows predictable trajectories. As we move forward in an era when genomic resources will be increasingly available, adaptive radiations offer additional advantages. Because recent rapid radiations have resulted in closely related taxa with distinct adaptive features, the genomes are likely to be remarkably similar overall, thus leaving relatively clear signals of which genes are likely involved with speciation and adaptation [e.g., Turner et al. (2005)]. Furthermore, the development of genomic tools for 1 species will likely be transferable to other taxa in an adaptive radiation (Abzhanov et al., 2008). Exploration of phenotypes in the field and their genetic basis provides a powerful approach for describing evolutionary processes that have shaped biodiversity. For the reasons outlined above, adaptive radiations maximize our ability to detect patterns and test both long-standing and emerging hypotheses about the nature of adaptive evolutionary change.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank John Avise and Francisco Ayala for the opportunity to discuss our work at the Sackler Colloquium and John Avise, Dolph Schluter, and an anonymous referee for providing comments that greatly improved the manuscript. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant EF-0412727.