17

Darwin’s “Strange Inversion of Reasoning”

DANIEL DENNETT

Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection unifies the world of physics with the world of meaning and purpose by proposing a deeply counterintuitive “inversion of reasoning” (according to a 19th century critic): “to make a perfect and beautiful machine, it is not requisite to know how to make it” [MacKenzie RB (1868) (Nisbet & Co., London)]. Turing proposed a similar inversion: to be a perfect and beautiful computing machine, it is not requisite to know what arithmetic is. Together, these ideas help to explain how we human intelligences came to be able to discern the reasons for all of the adaptations of life, including our own.

TWO STRANGE INVERSIONS OF REASONING

Some of the most important thinkers we philosophers take seriously were not philosophers but scientists—Newton, Einstein, Gödel, and Turing, for instance—but by far the scientist who has made the greatest contribution to philosophy is Charles Darwin. If I could give a prize for the single best idea anybody ever had, I’d give it to Darwin. In a single stroke Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection united

Center for Cognitive Studies, Tufts University, Medford, MA 02155-7059.

the realm of physics and mechanism on the one hand with the realm of meaning and purpose on the other. From a Darwinian perspective the continuity between lifeless matter on the one hand and living things and all their activities and products on the other can be glimpsed in outline and explored in detail, not just the strivings of animals and the efficient designs of plants, but human meanings and purposes: art and science itself, and even morality. When we can see all of our artifacts as fruits on the tree of life, we have achieved a unification of perspective that permits us to gauge both the similarities and differences between a spider web and the World Wide Web, a beaver dam and the Hoover Dam, a nightingale’s nest and “Ode to a Nightingale.” Darwin’s unifying stroke was revolutionary not just in the breadth of its scope, but in the way it was achieved: in an important sense, it turned everything familiar upside down. The pre-Darwinian world was held together not by science but by tradition: all things in the universe, from the most exalted (“man”) to the most humble (the ant, the pebble, the raindrop) were the creations of a still more exalted thing, God, an omnipotent and omniscient intelligent creator—who bore a striking resemblance to the second-most exalted thing. Call this the trickle-down theory of creation. Darwin replaced it with the bubble-up theory of creation. One of Darwin’s 19th century critics put it vividly:

In the theory with which we have to deal, Absolute Ignorance is the artificer; so that we may enunciate as the fundamental principle of the whole system, that, IN ORDER TO MAKE A PERFECT AND BEAUTIFUL MACHINE, IT IS NOT REQUISITE TO KNOW HOW TO MAKE IT. This proposition will be found, on careful examination, to express, in condensed form, the essential purport of the Theory, and to express in a few words all Mr. Darwin’s meaning; who, by a strange inversion of reasoning, seems to think Absolute Ignorance fully qualified to take the place of Absolute Wisdom in all of the achievements of creative skill.

MacKenzie (1868)

This was indeed a “strange inversion of reasoning,” and the outrage and incredulity expressed by MacKenzie more than a century ago is still echoing through a discouragingly large proportion of the population in the 21st century. A page from a 20th century creationist pamphlet (Fig. 17.1) perfectly captures the “obviousness” of the intuition that Darwin’s theory overthrows.

When we turn to Darwin’s bubble-up theory of creation, we can conceive of all of the creative design work metaphorically as lifting in Design Space. It has to start with the simplest replicators, and gradually ratchet up, by wave after wave of natural selection, to multicellular life in all its forms. Is such a process really capable of having produced all of the wonders we observe in the biosphere? Skeptics ever since Darwin have tried to demonstrate that one marvel or another is simply unapproachable

FIGURE 17.1 An expression of incredulity about Darwin’s inversion, from an anonymous creationist propaganda pamphlet, ca. 1970.

by this laborious and unintelligent route. They have been searching for a “skyhook,” something that floats high in Design Space, unsupported by ancestors, the direct result of a special act of intelligent creation. And time and again, these skeptics have discovered not a miraculous skyhook but a wonderful “crane,” a nonmiraculous innovation in Design Space that enables ever more efficient exploration of the possibilities of design, ever more powerful lifting in Design Space. Endosymbiosis is a crane; sex is a crane; language and culture are cranes. (For instance, without their addition to the arsenal of R&D tools available to evolution, we couldn’t have glow-in-the-dark tobacco plants with firefly genes in them. These are not miraculous. They are just as clearly fruits of the tree of life as spider webs and beaver dams, but the probability of their emerging without the helping hand of Homo sapiens and our cultural tools is nil.)

As we learn more and more about the nano-machinery of life that makes all this possible, we can appreciate a second strange inversion of reasoning, provided by another brilliant Englishman: Alan Turing. Here is Turing’s strange inversion, put in language borrowed from MacKenzie:

IN ORDER TO BE A PERFECT AND BEAUTIFUL COMPUTING MACHINE, IT IS NOT REQUISITE TO KNOW WHAT ARITHMETIC IS.

Before Turing there were computers, by the hundreds, working on scientific and engineering calculations. Many of them were women, and many had degrees in mathematics. They were human beings who knew what arithmetic was, but Turing had a great insight: they didn’t need to know this! As he noted, “The behavior of the computer at any moment is determined by the symbols which he is observing, and his ‘state of mind’ at that moment …” (Turing, 1936). Turing showed that it was possible to design machines—Turing machines or their equivalents—that were Absolutely

Ignorant, but could do arithmetic perfectly. And, he showed that, if they can do arithmetic, they can be given instructions in the impoverished terms that they do “understand” that permit them to do anything computational. (The Church-Turing Thesis is that all “effective procedures” are Turing-computable—although of course many of them are not feasible because they take too long to run. Because our understanding of effective procedures is unavoidably intuitive, this thesis cannot be proved, but it is almost universally accepted, so much so that Turing-computability is typically taken as an acceptable operational definition of effectiveness.) A huge Design Space of information-processing was made accessible by Turing, and he foresaw that there was a traversable path from Absolute Ignorance to Artificial Intelligence, a long series of lifting steps in that Design Space.

Many people can’t abide Darwin’s strange inversion. We call them creationists. They are still looking for skyhooks—”irreducibly complex” features of the biosphere that could not have evolved by Darwinian processes. Many people can’t abide Turing’s strange inversion either. I propose that we call them “mind creationists.” Among them are some eminent thinkers. They argue—so far with no more success than creationists—that there are aspects of (human) minds that are forever and “in principle” inaccessible by the long upward trudge of Turing machines. John Searle (1980, 1992) and Roger Penrose (1989, 1990) are the two best known. Interestingly, in the last few years, several philosophers have come close to embracing both species of creationism: Jerry Fodor (2007, 2008a,b), Thomas Nagel (2008), and Alvin Plantinga (1993, 1996, 2009). Fodor and Nagel deny that religion has anything to do with their skepticism about evolution. Fodor declares that his arguments provide no support for Intelligent Design because he isn’t saying that adaptations are due to an Intelligent Designer; he is saying that nobody knows how adaptations arose. He accepts descent with modification, but doesn’t think natural selection (“adaptation”) is the explanation of any features of living things. “It is in short one thing to wonder if evolution happens and another thing to wonder if adaptation is the mechanism by which it happens” (Fodor, 2008a). The paleontologist Simon Conway Morris (2009) takes a strikingly different tack: he wholeheartedly accepts adaptationism but still thinks that human minds are inexplicable as a product of natural selection unaided by the intelligence of a Christian God.

PLANTINGA’S ATTEMPTED REDUCTIO AD ABSURDUM OF NATURALISM

Plantinga also has an explicitly religious foundation for his repugnance, and he covers both kinds of creationism in his attempt at a reductio ad absurdum of naturalism (1996, 2009). Where N is naturalism, E is current

evolutionary theory and R is the proposition that our cognitive faculties are reliable:

-

P(R||IN&E) is low. [The probability of R, conditional on N&E, is low.]

-

One who accepts N&E sees that (1) is true has a defeater for R.

-

This defeater can’t be defeated.

-

One who has a defeater for R has a defeater for any belief she takes to be produced by her cognitive faculties, including N&E.

Therefore:

-

N&E is self-defeating and can’t rationally be accepted.

Plantinga (2009)

We needn’t dwell here on the interpretation of the whole argument because the crucial Premise 1 is false. We can see why in terms of evolution by natural selection. Consider the excellence and reliability of various organs. Across the entire spectrum of, say, vertebrates, hearts are highly reliable pumps, lungs are highly reliable blood oxygenators, and eyes and ears are highly reliable distal-information-acquirers. In each species there is admirable—but not perfect—tuning of these organs to the specific needs of the organisms in their demanding environments. The eagle’s eyes are strikingly unlike the rabbit’s eyes or the frog’s eyes. The effect is that the beliefs (or if you’re abstemious about using that term, the information states) that are provoked by those eyes and ears are highly reliable—but far from perfect—truth-trackers. Animals that get it right in general fare better than those whose senses deceive them.

This is adaptationist reasoning, of course, and it is not surprising that creationists of both kinds have typically taken aim at adaptationist thinking in biology, for they see, correctly, that if they can discredit it, they take away the only grounds within biology for assessing the justification or rational acceptability of the deliverances of such organs. We need to put matters in these “reverse engineering” terms if we are to compare organs with respect to their reliability—and not just their mass or density or use of phosphorus, for instance. Such an appeal to the power of natural selection to design highly reliable information-gathering organs would be in danger of vicious circularity were it not for the striking confirmations of these achievements of natural selection using independent engineering measures. The acuity of vision in the eagle and hearing in the owl, the discriminatory powers of electric eels and echolocating bats, and many other cognitive talents in humans and other species have all been objectively measured, for instance.

It might seem that the skeptics could short-circuit this defense of our natural reliability as truth-trackers by showing that there can be no gradualistic path to truth-tracking. They could claim that there are no quasi-

believers, proto-thinkers, hemi-semidemi-understanders; you either have a full-blown mind or you don’t. This is where Turing’s strange inversion comes usefully into play, for his insight has given us a wealth of undeniable examples of just such partial comprehension: devices that can do all manner of impressive discriminative, predictive, and analytic tasks. We may insist on calling this competence without comprehension, but, as the competence grows and grows, the declaration that there is no comprehension at all embodied in that competence sounds less and less persuasive. This is made especially vivid when we reflect that, as we learn more about the nano-technology within our cells, we discover that they themselves contain trillions of protein robots: motor proteins, proofreaders, snippers, and joiners and sentries of all kinds. It is undeniable that the other necessary competences of life are composable from unliving, uncomprehending parts; why should comprehension itself be the lone exception?

In the gradual path to intelligence, endosymbiosis has played a particularly potent role as a crane. The endosymbiotic origin of the eukaryotic revolution ≈2.5 billion years ago gives us a telling example of a quite sudden multiplication of competence: each partner in the symbiosis got the potential benefit of over a billion years of independent R&D, a tremendous acquisition of talent not found in one’s ancestors. Instead of eating the intruder—disassembling it for raw materials and energy—the host coopted the intruder, preserving most or all of the valuable information embodied in its design. The greater complexity of the resulting eukaryotes permitted greater versatility, allowing for the sorts of division of labor that enabled multicellularity to evolve. (As Lukeš et al., Chapter 4, this volume, show, the evolution of multicellularity also involved reducing the complexity of prokaryotic replication methods, which were temporally and energetically too inefficient to support the profligate cell division of viable multicellular organisms.)

FREE-FLOATING RATIONALES OF EVOLUTION

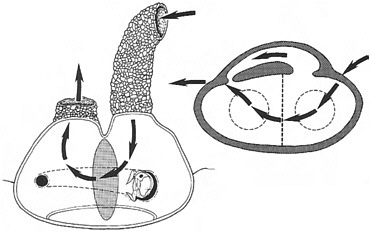

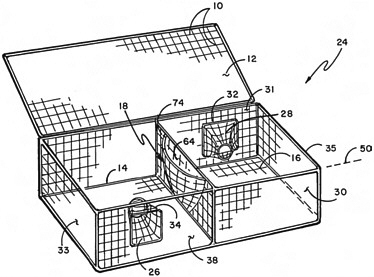

When we observe the caddis fly’s impressive food sieve (Fig. 17.2) we can see that there are reasons for its features that are strikingly similar to the reasons for the features of another artifact for harvesting food from water, the lobster trap (Fig. 17.3).

The difference is that the reasons in the former case are not represented anywhere. Not in the caddis fly’s “mind” or brain, and not in the process of natural selection that “honored” those reasons by blindly homing in on the best design. These are examples of the ubiquitous “free-floating rationales” of evolution (Dennett, 1995). Some of the features of the lobster trap may be similarly the result of blind trial and error by trap-makers over the centuries, but there is little doubt that most if not all of the reasons

FIGURE 17.2 A caddis larva food sieve, exhibiting design features for which there are good (unrepresented) reasons (Hansell, 2000) that are strikingly similar to the reasons for the features of another artifact for harvesting food from water, the lobster trap (see Fig. 17.3).

SOURCE: Reproduced with permission from Hansell (2000) (Copyright 2000, Cambridge University Press).

FIGURE 17.3 Lobster trap diagram, exhibiting design features similar to those of the caddis larva food sieve (see Fig. 17.2); the reasons for the design features are described in the patent application (available at www.freepatentsonline.com/7111427.html).

SOURCE: Reproduced with permission from United States Patent 7111427.

for the design features instantiated by today’s lobster traps have been represented, understood, appreciated, and communicated by their (more or less intelligent) artificers.

Consider the murderous behavior of the cuckoo chick, pushing the eggs of the host out of the nest to maximize its food intake. The rationale for this behavior is unmistakable, but the chick has no Need to Know; it can be the beneficiary of a routine that it follows without any comprehension of its rationale. This is Turing’s strange inversion uncovered in nature. There is a common tendency to overinterpret animals exhibiting such clever behaviors, imputing to them much more comprehension than they need, or have, and an equally common tendency, in reaction, to underestimate them. The literature on animal intelligence reverberates with the contests between the romantics and the killjoys (Dennett, 1983), and long series of ingenious experiments are gradually limning the actual boundaries of these competences. Because we don’t have everyday terms for semi-understood quasi-beliefs, we have no stable vocabulary for describing the cascade of Turing powers that climbs to the summit of our particular human levels of comprehension. Is it “metaphorical” to attribute beliefs to birds or chimpanzees? Should we reserve that term, and many others, for (adult) human beings alone? This lexical dearth helps to sustain the illusion that there is an unbridgeable gulf between animal minds and human minds—despite the obvious fact that similar quandaries of interpretation afflict us when we turn to young children. Just when do they exhibit enough prowess in one test or another for us to say, conclusively, that they “have a theory of mind” or understand numbers? How much do we human beings need to know to understand our own concepts? There is no good, principled answer to this question.

EVOLUTION OF THINKING TOOLS

Rather than attempt to answer such an ill-motivated question about necessary and sufficient conditions we can simply acknowledge, with Maynard Smith and Szathmary (1995), that along the path from amoebas and cuckoos to us, there was a major transition with powers to rival the endosymbiotic birth of the eukaryotes: the evolution of language and culture, one of the great cranes of evolution. In both cases, individual organisms were enabled to acquire, rapidly and without tedious trial and error, huge increases in competence designed elsewhere at earlier times. The effects have been dramatic indeed. According to calculations by MacCready, at the dawn of human agriculture, the worldwide human population plus livestock and pets was ≈0.1% of the terrestrial vertebrate biomass. Today, he calculates, it is 98%!

Over billions of years, on a unique sphere, chance has painted a thin covering of life—complex, improbable, wonderful and fragile. Suddenly we humans … have grown in population, technology, and intelligence to a position of terrible power: we now wield the paintbrush.

MacCready (1999)

Unlike the biologically “sudden” Cambrian explosion, which occurred over several million years ≈530 million years ago (Gould, 1989), the MacCready explosion occurred in ≈10,000 years, or ≈500 human generations. There is no doubt that it was the rapidly accumulating products of cultural evolution that made this possible. As Richerson and Boyd (2006) show, in addition to the standard highway, the vertical transmission of genes, a second information highway from parents to offspring is evolvable under rather demanding conditions; and once this path of vertical cultural transmission is established and optimized, it can be invaded by “rogue cultural variants,” horizontally or obliquely transmitted cultural items that do not have the same probability of being benign. (The comparison to spam on the internet is hard to avoid.) These rogue cultural variants are what Richard Dawkins (1976) calls “memes,” and although some of them are bound to be pernicious—parasites, not mutualists—others are profound enhancers of the native competences of the hosts they infect. One can acquire huge amounts of valuable information of which one’s parents had no inkling, along with the junk and scams.

Language is the key cultural element, because it alone provides the digitized base for reliable cumulative evolution. (It is digitized in the sense that it is composed of a finite set of discrete, all-or-nothing elements—phonemes—that can survive noisy transmission, different accents and tones of voice, drawls and lisps, by a process of largely automatic correction to norms.) Other species, such as chimpanzees, have a handful of culturally transmitted traditions—of termite fishing or grooming signals or nut cracking, for instance—but nothing that ramifies the way human culture does. Language, by providing a basic repertoire of readily replicated elements, permits the reliable transmission of semi-understood formulas, recipes, admonitions, techniques. (It is not typically noticed that one of the most valuable features of language is its ability to convey information down a chain of communicators who do not really understand what they are “parrotting.”) By rendering copying and transmission relatively impervious to variations in comprehension, language optimizes fidelity in the pathway. Words, composed of a finite “alphabet” of phonemes, share with computers and the genetic code the self-normalizing feature of absorbing noise, or permitting many minor variations to “count as the same” for the purposes of computation or replication. This makes it

possible, using language, to create fairly “standardized” thinking tools. Douglas Hofstadter (2007) provides a short list of some of his favorites:

-

wild goose chases

-

tackiness

-

dirty tricks

-

sour grapes

-

elbow grease

-

feet of clay

-

loose cannons

-

crackpots

-

lip service

-

slam dunks

-

feedback

Each of these is an abstract cognitive tool, in the same way that long division or finding-the-average is a tool; each has a role to play in a broad spectrum of contexts, rendering hypothesis generation more efficient, pattern recognition more probable. Equipped with such tools one is able to think thoughts that would otherwise be relatively hard to formulate. Of course, as the old joke has it, when the only tool you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail, and each of these can be overused. Acquiring tools and using them wisely are distinct skills, but you have to start by acquiring the tools.

BOOTSTRAPPING OUR WAY TO INTELLIGENT DESIGN, AND TRUTH

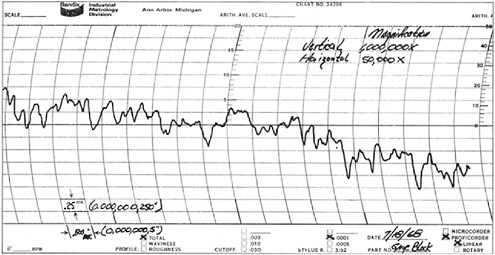

In fact, the development of cultural tools for thinking, for designing, for extracting and recording information have led to orders of magnitude of improvement in all our belief-forming competences. Consider, as just one simple example, the evolution of the straightedge. How do you draw a straight line? By placing a pencil on a straightedge and running it across the paper. Where did you get the straightedge? From a straightedge-maker. Where did the straightedge-maker get the straightedge used to make this product? From some earlier toolmaker, and so on, but not to infinity. This is an instance of nonmiraculous bootstrapping, and it has occurred many times. There is a finite regress leading back to the earliest relatively primitive and inaccurate straightedges, but, over time, straightedges have been manufactured to ever more demanding tolerances. The deviations from perfection manifest in a straightedge from the 1960s are shown in Fig. 17.4, magnified a millionfold. Such representations make possible highly efficient, guided, foresighted trajectories in design space.

FIGURE 17.4 A surface trace of a precision gauge block at 1 million times vertical magnification, illustrating the representation of deviations from perfection.

SOURCE: Reproduced with permission from Moore (1970) (Copyright 1970, Moore Special Tool Company).

And our indefinitely extendable recursive power of reflection means that not only can we evaluate our progress, but we can evaluate our evaluation methods, and the grounds for relying on evaluation methods, and the grounds for thinking that this iterative process gives us grounds for believing the best fruits of our research, and so forth. Science is a culturally transmitted and maintained system of truth-tracking that has identified and rectified literally hundreds of imperfections in our animal equipment, and yet it is not itself a skyhook, a gift from God, but a product of adaptations, a fruit on the tree of life.

That is, in outline, the response to Plantinga’s premise (MacKenzie, 1868). We have excellent internal evidence for believing that science in general is both reliable and a product of naturalistic forces only—natural selection of genes and natural selection of memes. An allegiance to naturalism and to current evolutionary theory not only doesn’t undermine the conviction that our scientific beliefs are reliable; it explains them. Our “godlike” powers of comprehension and imagination do indeed set us apart from even our closest kin, the chimpanzees and bonobos, but these powers we have can all be accounted for on Darwin’s bubble-up theory of creation, clarified by Turing’s own strange—and wonderful—inversion of reasoning.

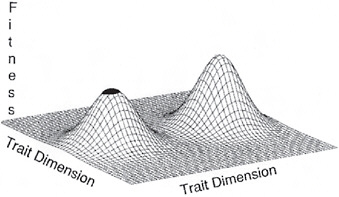

Our powers of representation permit us, for instance, to represent some of our predicaments as locations on adaptive landscapes (Fig. 17.5).

FIGURE 17.5 Adaptive landscape, which can be used as an explicit representation of valuable states of affairs or goals, relative to one’s current situation.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from Schull (1991) (Copyright 1991, Springer).

Here, we are, we may think, isolated on this sup-optimal peak; is there any way of getting over there, to what seems to be the global summit? Because we can represent this state of affairs (in diagrams or words—you don’t need to use adaptive landscape sketches, but they often help), we can, for the first time, “see” some of the peaks beyond the valleys, and thereby are motivated to devise ways of traversing those valleys. We, the reason representers, can evaluate our possible futures far more powerfully, far less myopically, than any other species, can now look back at our own prehistory and discover the unrepresented reasons everywhere in the tree of life.

We are not perfect truth-trackers, but we can evaluate our own shortcomings by using the methods we have so far devised, so we can be confident that we are justified in trusting our methods in the foreseeable future.

It took Darwin to discover that a mindless process created all those reasons. We “intelligent designers” are among the effects, not the cause, of all those purposes.