3

Genetics and Ecological Speciation

DOLPH SCHLUTER and GINA L. CONTE

Species originate frequently by natural selection. A general mechanism by which this occurs is ecological speciation, defined as the evolution of reproductive isolation between populations as a result of ecologically based divergent natural selection. The alternative mechanism is mutation-order speciation in which populations fix different mutations as they adapt to similar selection pressures. Although numerous cases now indicate the importance of ecological speciation in nature, very little is known about the genetics of the process. Here, we summarize the genetics of premating and postzygotic isolation and the role of standing genetic variation in ecological speciation. We discuss the role of selection from standing genetic variation in threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus), a complex of species whose ancestral marine form repeatedly colonized and adapted to freshwater environments. We propose that ecological speciation has occurred multiple times in parallel in this group via a “transporter” process in which selection in freshwater environments repeatedly acts on standing genetic variation that is maintained in marine populations by export of freshwater-adapted alleles from elsewhere in the range. Selection from standing genetic variation is likely to play a large role in ecological speciation, which may partly account for its rapidity.

Biodiversity Research Centre and Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z4.

One of Darwin’s greatest ideas was that new species originate by natural selection (Darwin, 1859). It has taken evolutionary biologists almost until now to realize that he was probably correct. Darwin looked at species mainly as sets of individuals closely resembling each other (Darwin, 1859), in which case adaptive divergence in phenotype eventually leads to speciation almost by definition. Later, Dobzhansky (1937) and Mayr (1942) defined species and speciation by the criterion of reproductive isolation instead. Recent evidence indicates that reproductive isolation also evolves frequently by natural selection (Schluter, 2000, 2009; Coyne and Orr, 2004; Price, 2008).

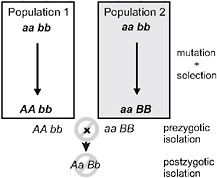

Speciation by natural selection occurs by 2 general mechanisms (Price, 2008; Schluter, 2009). The first of these is ecological speciation, defined as the evolution of reproductive isolation between populations, or subsets of a single population, as a result of ecologically based divergent natural selection (Schluter, 2000, 2001; Rundle and Nosil, 2005; Funk, 2009). Under this process natural selection acts in contrasting directions between environments, which drives the fixation of different alleles, each advantageous in one environment but not in the other (Fig. 3.1). In contrast,

FIGURE 3.1 A simple genetic model for speciation by natural selection, after Dobzhansky (1937). Two initially identical populations accumulate genetic differences by mutation and selection. In population 1, mutation A arises and spreads to fixation, replacing a, whereas mutation B replaces b in population 2. Selection is divergent under ecological speciation, favoring allele A over a in one environment and B over b in the other (emphasized by shading). Under the alternative mutation-order process, selection is uniform and favors A and B in both environments, with divergence then occurring by chance. If A and B are “incompatible” then populations in contact will produce fewer hybrids than expected (prezygotic isolation) or hybrids will be less fit (postzygotic isolation). The process is identical if instead both genetic changes occur sequentially in one population and the other retains the ancestral state. For example, the final genotypes shown could occur instead if the ancestral genotype is AAbb, and a replaces A, and then B replaces b in population 2.

under mutation-order speciation (Mani and Clarke, 1990; Schluter, 2009), populations diverge as they accumulate a different series of mutations under similar selection pressures (Fig. 3.1). Natural selection drives alleles to fixation in both speciation mechanisms, but selection favors divergence only under ecological speciation. Divergence occurs by chance under the mutation-order process.

There is growing evidence in support of both ecological and mutation-order speciation in nature (Price, 2008; Schluter, 2009), yet numerous aspects of these mechanisms remain obscure. One of the most glaring deficiencies is the almost complete absence of information on the genetics of ecological speciation. Here, we review several aspects of the problem. We address characteristics of genes underlying premating isolation; the evolution and genetics of postzygotic isolation; and the role of standing genetic variation as a source of alleles for the evolution of reproductive isolation. Although data are not plentiful, it is possible to reach some conclusions about how the genetic process of ecological speciation should work and how it might differ from that mutation-order speciation. We end with a summary of evidence for ecological speciation in a threespine stickleback system and address the possible role of standing genetic variation in their adaptation to freshwater environments. We present a hypothesis for the repetitive origin of freshwater stickleback species involving natural selection of standing genetic variation.

GENETICS OF PREMATING ISOLATION

Premating isolation is the reduced probability of mating between individuals from different populations as a result of behavioral, ecological, or other phenotypic differences. In ecological speciation, premating isolation is of 2 general types. The first is selection against migrants or “immigrant inviability” between locally adapted populations (Via et al., 2000; Nosil et al., 2005). Interbreeding is reduced when spatial proximity of individuals is required for mating, and when the survival, growth, or reproductive success of immigrant individuals is diminished because their phenotype is less well adapted than the resident population to local conditions. This form of premating isolation is unique to ecological speciation, although it is not always present (e.g., when populations or gametes move between environments during mating). Immigrant inviability can account for a high fraction of total reproductive isolation (Nosil et al., 2005; Lowry et al., 2008).

Because it arises from direct selection on the phenotypes of individuals, the genetics of immigrant inviability is identical to the genetics of local adaptation. Any locus under divergent natural selection between parental environments contributes to immigrant inviability and therefore

may contribute to speciation. The contribution to reproductive isolation increases directly with the strength of selection on genes (Rice and Hostert, 1993; Nosil et al., 2009). For example, Hawthorne and Via (2001) discovered several quantitative trait loci (QTL) responsible for host-specific performance of specialized aphid populations. Each type survives poorly on the other’s host plant. Because aphids must survive in their chosen habitat to mate there, these QTL indirectly influence who mates with whom (Via et al., 2000). Color pattern differences under divergent selection between spatially separated species of Heliconius butterflies map to a QTL identified as wingless (Kronforst et al., 2006). The hybrid sunflower Helianthus paradoxus inhabits salt marshes in which both its parent species have reduced viability. Reduced viability of the parental species in this habitat mapped to a QTL identified as the salt tolerance gene CDPK3 (Lexer et al., 2004). Great progress is now being made in identifying genes responsible for local adaptation in natural populations (Abzhanov et al., 2008). The contribution of such genes to the evolution of reproductive isolation, however, should not be assumed until the magnitudes of effects are quantified in nature.

Assortative mating is the other component of premating reproductive isolation important to ecological speciation. The genetic mechanisms that permit its evolution and/or persistence have received considerable attention, particularly when there is gene flow between populations. Felsenstein (1981) pointed out that in the absence of very strong reproductive isolation between hybridizing populations, recombination between genes governing assortative mating and genes under divergent natural selection will cause existing levels of assortative mating between populations to decay and inhibit the evolution of even stronger assortative mating. Numerous ways around this dilemma have been proposed (Gavrilets, 2004), including low recombination between the genes for assortative mating and those under divergent selection, close proximity between genes for assortative mating and genes under divergent selection, and pleiotropic effects of the genes under divergent selection on assortative mating. Finally, the dilemma is overcome by the evolution of a “1-allele” mechanism for premating isolation in which individuals choose mates according to their values of a trait under divergent selection (e.g., “mate with someone the same size as oneself”) (Felsenstein, 1981).

Genetic mechanisms for premating isolation that overcome the antagonism between selection and recombination have been confirmed in nature. For example, genes for assortative mating between host-specialized aphid populations map to the same regions of the genome as those determining performance on the alternative host plants (Hawthorne and Via, 2001). Adaptive differences in wing color patterns between Heliconius butterfly species are also cues in assortative mating, and both trait and assorta-

tive mating map to the same candidate gene, wingless (Kronforst et al., 2006). Finally, the YUP locus and other QTL affecting flower color and shape differences between the monkeyflowers Mimulus cardinalus and Mimulus lewisii have pleiotropic effects on assortative mating through their attractiveness to alternative pollinators (Schemske and Bradshaw, 1999; Bradshaw and Schemske, 2003).

DIVERGENT SELECTION AND POSTZYGOTIC ISOLATION

The genetics of postzygotic isolation in ecological speciation has received little attention. Ecological speciation uniquely predicts the evolution of ecologically based postzygotic isolation (also called “extrinsic,” or “environment-dependent” reproductive isolation). As populations in different environments evolve toward different adaptive peaks, intermediate forms, including hybrids, increasingly fall between the peaks and suffer reduced fitness in both parental environments (Hatfield and Schluter, 1999; Rundle and Whitlock, 2001; Schluter, 2001). Such ecologically dependent hybrid fitness has been detected in a few study systems, including pea aphids (Via et al., 2000) and threespine stickleback (Rundle, 2002). The fitness of hybrids between divergently adapted populations may also be affected by heterosis (hybrid vigor), especially in the F1 hybrids (Barton, 2001), and this has not been controlled in most field estimates of ecologically based postzygotic isolation. However, if heterosis is strong the impact of ecologically based postzygotic isolation is diminished (Lowry et al., 2008).

Most of the populations and species that have been studied from an ecological perspective are young and appear to manifest little “intrinsic” (environment-independent) postzygotic isolation. Exceptions include mine populations of Mimulus guttatus, which possess an unidentified copper tolerance gene or gene complex that is favored by ecological selection but that interacts with 1 or more other loci to cause the death of F1 hybrids in crosses to nonmine populations (MacNair and Christie, 1983). Another exception involves sympatric dwarf and normal forms of lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis), which show elevated mortality of embryos (Rogers and Bernatchez, 2006). In a laboratory experiment, Dettman et al. (2007) recorded intrinsic postzygotic isolation affecting growth rate and frequency of meiosis in hybrids between yeast populations that had evolved for 500 generations in 2 distinct environments. Without more evidence on the mechanism of selection we are unable to determine which, if any, of the genes recently discovered to underlie intrinsic postzygotic isolation in Drosophila, yeast, and mice (Coyne and Orr, 2004; Brideau et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2008; Mihola et al., 2009; Tang and Presgraves, 2009) fixed as a result of ecologically based divergent natural selection.

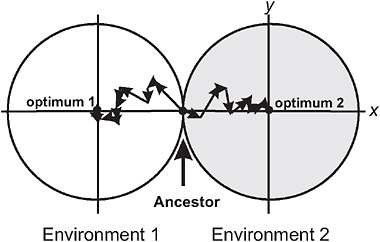

Barton (2001) used the Fisher-Orr geometric model of adaptation (Orr, 1998) to demonstrate that both intrinsic and extrinsic postzygotic isolation should evolve as a by-product of adaptation to contrasting environments. To illustrate, he assumed that divergent selection acted on just a single trait between populations (Fig. 3.2), whereas multiple additional traits were under stabilizing selection, favoring the same mean in both environments. Mutations were assumed to be pleiotropic, which means that while they change the population mean for the trait under directional selection in each environment, they have the side-effect of changing the mean in other traits, too. As each population attains its local adaptive peak by a sequence of mutational steps, advantageous mutations fixing later compensate for deleterious side-effects of advantageous mutations that fixed earlier (Fig. 3.2). These compensatory mechanisms fail in hybrids containing a sample of mutations from each of the parent populations, resulting in a phenotype that deviates from the optimum in the secondary traits (Barton, 2001). Thus, as populations adapt to different environments, the fitness of hybrids between them evolves below that predicted from the hybrid’s phenotype for the trait under divergent selection, the amount depending on genetic details such as

FIGURE 3.2 A model for the buildup of postzygotic isolation between 2 populations descended from a common ancestor adapting to distinct ecological environments, after Barton (2001). The perimeter of each circle represents a contour of equal fitness; fitness in each environment is higher inside the circle than outside. Trait x is under divergent natural selection, represented by separate adaptive peaks. Other traits, here represented by a single dimension y, are under stabilizing selection in both environments, as indicated by identical optima along this axis. A population adapts by fixing new advantageous mutations that bring the mean of trait x toward the optimum. An example of a sequence of adaptive steps is shown for each population by the linked arrow segments.

dominance relationships at individual loci. This extra component of postzygotic isolation is intrinsic in that it is manifested in both environments, and it represents a Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibility (Coyne and Orr, 2004) because it results from an interaction within hybrids of genes that are favored in the genetic background of the parent populations. Barton (2001) pointed out that the model might not be able to account for cases of very strong hybrid incompatibility, such as the lethality of gene combinations in hybrids between mine and nonmine populations of M. guttatus.

Surprisingly, Barton (2001) also found that intrinsic postzygotic isolation evolves just as readily between populations experiencing parallel selection as between populations under divergent selection. This finding conflicts with empirical studies that typically find faster evolution of reproductive isolation, including intrinsic postzygotic isolation (Dettman et al., 2007), between populations adapting to different environments than between populations adapting to similar environments (Rice and Hostert, 1993; Schluter, 2000, 2001). Broad comparative studies have found that intrinsic postzygotic isolation is highest between species that are ecologically differentiated (Bolnick et al., 2006; Funk et al., 2006). This discrepancy may be accounted for by features of nature not incorporated in the model. For example, Barton’s model assumes that adaptation occurred entirely from new mutations of which an infinite variety is available. Yet, the number of advantageous mutations for a given trait may be restricted, with the result that the same mutations occur and fix repeatedly under parallel selection (Palmer and Feldman, 2009; Unckless and Orr, 2009), preventing divergence. The same is expected if populations adapt from the same standing genetic variation (Colosimo et al., 2005; Barrett and Schluter, 2008) and if there is gene flow between separate populations evolving under parallel selection (Morjan and Rieseberg, 2004). Finally, divergent selection may be more effective than parallel selection simply because it acts on more traits and on more genes (Nosil et al., 2009). These factors help to explain why ecological speciation may generally be faster than mutation-order speciation even though selection is driving alleles to fixation under both mechanisms.

ECOLOGICAL SPECIATION FROM STANDING GENETIC VARIATION

Speciation occurs from standing genetic variation when reproductive isolation between 2 or more populations evolves from alleles already present within the common ancestral population, rather than from new mutations. Theory to describe the buildup of Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities often explicitly assumes that speciation occurs from new mutations [e.g., Barton (2001) and Gavrilets (2003)] rather than from standing

variation. In contrast, quantitative genetic models of speciation assume that response to selection, at least in the early stages of divergence, is based on standing genetic variation (Dieckmann and Doebeli, 1999; Burger and Schneider, 2006). There is little direct evidence for either assumption (Noor and Coyne, 2006). The topic is interesting because speciation from standing variation is potentially more rapid than that from new mutations, because the waiting time for new mutations is skipped and alleles present as standing variation begin at higher frequency (Hermisson and Pennings, 2005; Barrett and Schluter, 2008). Standing genetic variation can result in the same alleles being used repeatedly in separate speciation events, enhancing the probability of parallel evolution of reproductive isolation.

The apple maggot, a recently evolved race of the haw fly, Rhagoletis pomonella, provides a possible example of standing genetic variation contributing to speciation. The haw fly exploits haw fruits, but in the 1880s it expanded its host range to domestic apple. Haw and apple differ in their peak fruiting times, and accordingly the 2 races have diverged in pupal diapause traits (affecting overwinter dormancy) that also affect their timing of emergence as adults. This seasonal difference contributes to strong (although still incomplete) reproductive isolation. Significantly, racial differences in pupal diapause traits map to genomic regions that are polymorphic for chromosomal inversions. Each inverted version of a specific chromosomal region is at higher frequency in the apple race than in the ancestral haw race (Feder et al., 2003b). Remarkably, phylogenies based on gene sequences within the inverted regions reveal that the inversions themselves are old and that they occur as standing variation within R. pomonella across its geographic range. The frequency of the inversions declines from the southern to northeastern United States (Feder et al., 2003a). The pattern suggests that formation and divergence of the apple race involved selection of preexisting genetic variation for pupal diapause traits located on inversions, although the presence of these traits in southern populations needs to be confirmed.

A second possible example occurs in the Lake Victoria cichlids, Pundamilia pundamilia and Pundamilia neyereri, which have different alleles at the long-wave sensitive opsin gene. These alleles affect sensitivity to wavelengths of ambient light at the different depths in the lake where the 2 species reside (Seehausen et al., 2008), and they may also influence the color (red vs. blue) of males chosen by breeding females, contributing to assortative mating. However, whereas the red and blue Pundamilia are sister species, each being the other’s closest relative, the 2 long-wave-sensitive alleles are not sister lineages on the phylogenetic tree of opsin gene sequences (Seehausen et al., 2008). Rather, the 2 opsin alleles share a common ancestral opsin sequence at a time well before the divergence of the 2 Pundamilia species, perhaps even before the appearance of Lake Victoria itself. This implies that speciation in Pundamilia used preexisting genetic variation.

In the next section we evaluate the possibility of speciation from standing genetic variation in threespine stickleback, a model system for which considerable evidence of ecological speciation has accumulated.

ECOLOGICAL SPECIATION FROM STANDING VARIATION IN STICKLEBACK

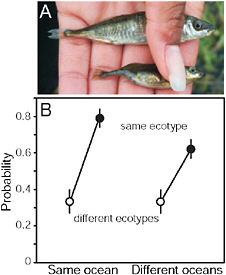

We focus on progress in understanding ecological speciation between adjacent marine and stream-resident threespine stickleback populations. The marine species or ecotype is the ancestral form to all freshwater populations. Most marine populations are anadromous, migrating to streams to breed and returning to sea afterward. While breeding in streams they may encounter stream-resident stickleback populations that are highly divergent in morphology and behavior (Fig. 3.3A) but that are descended within the past 10,000 years or so from the same marine form. In many streams the 2 forms show little introgression and exhibit premating isolation when measured in the laboratory (McKinnon et al., 2004).

FIGURE 3.3 Parallel speciation between marine and stream-resident stickleback. (A) Photo showing typical specimens from the marine (Upper) and stream-resident populations (Lower). The forms differ in defensive body armor and body size (both greater in the marine form), along with many other morphological traits. (Photo by J. McKinnon.) (B) Mating compatibility between males and females taken from different marine and stream stickleback populations around the Northern Hemisphere. Compatibility is measured by the proportion of mating trials reaching the penultimate stage of the courtship sequence. Fish were sampled from multiple populations in both the Atlantic and Pacific ocean basins.

SOURCE: Reproduced with permission from McKinnon et al. (2004) (Copyright 2004, Nature Publishing Group).

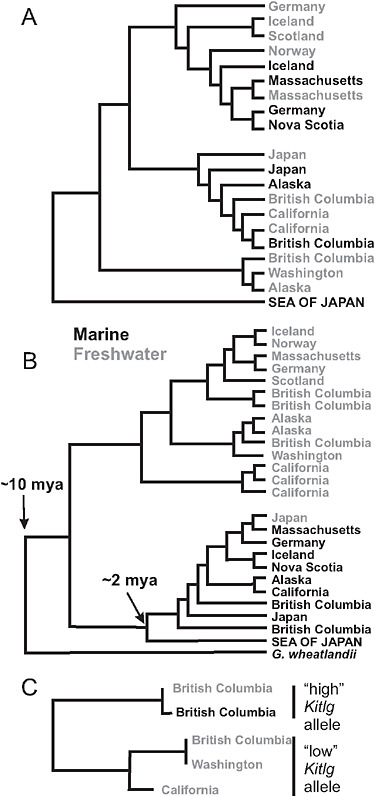

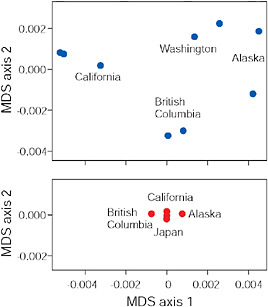

The stream stickleback populations exhibit rampant parallel evolution of morphological traits. Virtually everywhere it occurs, the stream ecotype is smaller in size, less streamlined in shape, and has reduced armor compared with the marine species. Size and other differences between stickle-back populations have been shown in laboratory common-garden studies to be substantially heritable (McKinnon et al., 2004). Phylogenies based on microsatellite markers (McKinnon et al., 2004) and nuclear gene SNPs (Fig. 3.4A) suggest that the stream ecotype has originated multiple times independently in coastal bodies of water around the Northern Hemisphere. The ancestral marine form has persisted over this same period in similar but geographically widespread marine habitats. The parallel evolution of stream forms, and the maintenance of the large anadromous phenotype in often distant but similar marine habitats, suggests that morphological differences between the freshwater and anadromous forms represent adaptations to contrasting environmental selection regimes (McKinnon et al., 2004).

The alternative explanation for these phylogenetic data (Fig. 3.4A) is that each freshwater population was formed by individuals immigrating directly from other freshwater populations nearby, via the sea, and that subsequent gene flow between adjacent marine and stream populations erased the signature of freshwater-to-freshwater colonization at neutral marker loci. However, this alternative hypothesis is difficult to reconcile with years of observational studies that find freshwater-adapted alleles in the sea (see below) but no freshwater individuals. Direct movement of fish between closely adjacent streams emptying into the sea might be feasible, but migration of freshwater individuals between streams in separate ocean basins and across other long distances is very unlikely.

The strongest evidence for ecological speciation in this group comes from a test of “parallel speciation” demonstrating repeated evolution of reproductive isolation between populations across a similar environmental gradient (McKinnon et al., 2004). When brought to the laboratory, individuals from different populations were more likely to mate with one another if they were the same ecotype and came from the same type of

FIGURE 3.4 Phylogenies of populations and genes. (A) Global phylogeny of marine and freshwater populations of threespine stickleback based on SNP markers at a sample of 25 nuclear genes. High-armor, marine populations are in black, low-armor freshwater populations are in gray. (B) Global phylogeny of Eda gene sequences from marine high-armor and freshwater low-armor stickleback populations. The Eda sequence in Gasterosteus wheatlandi was used as the outgroup. (C) Phylogeny of Kitlg sequences from 4 freshwater and 1 marine population in the Pacific basin. Branch lengths are not scaled to a comparable age between plots. SOURCE: A and B are reproduced with permission from Colosimo et al. (2005) (Copyright 2005, American Association for the Advancement of Science). C is reproduced with permission from Miller et al. (2007) (Copyright 2007, Elsevier).

environment (e.g., both were from streams, or both were from the sea) than if they were from different environments (i.e., one was marine and the other was from a stream) (Fig. 3.3B). This was true even in those mating trials involving fish sampled from separate ocean basins (Fig. 3.3B). Such a consistent pattern of phenotypic divergence implies that divergent natural selection is driving the evolution of reproductive isolation between marine and stream populations.

Body size appears to be an important trait influencing mating compatibility (McKinnon et al., 2004). Fish from different populations were more likely to mate with one another if they were similar in body size than if they were different in size. In addition, altering body size of females experimentally (by food and density manipulation) changed between-population mate preferences in the predicted direction: reducing female size increased mating probability with the small stream males, whereas increasing female size increased mating probability with large marine males. These findings imply that the differences in body size between marine and stream populations are partly responsible for assortative mating. Size differences between stickleback populations are partly heritable when fish are grown in a laboratory common garden (McKinnon et al., 2004). In the “common garden” of the wild, adult body size difference between marine and stream fish breeding in the same stream are also likely to be enhanced by the divergent habitat choices of young fish (i.e., to remain in the stream or migrate to sea), a decision presumably also under genetic control. In contrast, body size variation generated by phenotypic plasticity within populations likely weakens reproductive isolation between marine and stream populations.

The genes underlying assortative mating between marine and stream populations have not yet been located and identified. However, studies linking assortative mating to body size differences suggest that a large part of premating isolation between marine and stream populations will be determined by genes underlying ordinary phenotypic traits. Possibly, strong selection maintaining phenotypic differences between adjacent marine and stream populations negatively impacts the fitness of hybrids, which would also contribute to postzygotic isolation. These considerations justify looking to genes causing phenotypic differences between marine and freshwater populations as a first step toward understanding the genetics of reproductive isolation in this group.

Studies of genes underlying phenotype traits implicate selection from standing genetic variation in marine-freshwater divergence events. An example is Ectodysplasin (Eda), a gene that accounts for most of the transition from a marine phenotype having a large number of bony plates down each side of the body to the armor-reduced forms found almost everywhere in freshwater (Colosimo et al., 2005). One of the most remarkable discoveries about this gene is that the low-armor Eda allele found in

almost every freshwater population around the Northern Hemisphere belongs to the same clade of low-armor alleles (Fig. 3.4B). The origin of this clade predates the ages of all known freshwater populations, in most cases by orders of magnitude, suggesting that the original low-armor mutation occurred long ago. This fact implies that low-armor alleles were brought into lakes and streams by the marine species when it colonized those waters at the end of the last ice age ≈10,000 years ago. Sampling has confirmed that the partly recessive, low-armor allele is present as standing variation in the marine population (Colosimo et al., 2005; Barrett et al., 2008). Approximately 1% of marine adult fish are heterozygous at the Eda locus, containing 1 low- and 1 high-armor allele, which represents ample standing variation for selection to act on in freshwater.

It is likely that other traits in freshwater stickleback populations are the result of selection of standing genetic variation brought from the sea. We now have a second example of this in Kitlg, a gene responsible for lighter skin pigmentation in a subset of freshwater stickleback populations (Miller et al., 2007). Not as many populations have been surveyed as in the case of Eda, but the low-pigmentation alleles present in 3 freshwater populations in British Columbia, Washington state, and California form a monophyletic clade (Fig. 3.4C). This finding again implies that the allele was present in the marine population at the time of freshwater colonization and has been repeatedly selected in widespread freshwater populations.

Given these findings for Eda and Kitlg, it would not be far-fetched to suppose that the same process of repeated selection from standing genetic variation has occurred at many loci. Selection from standing variation provides a ready explanation for rapid parallel evolution in so many phenotypic traits that characterizes this group, including those affecting reproductive isolation. However, the question remains as to where the standing variation in the sea comes from and how it is maintained. Below, we develop the hypothesis that standing variation in the ancestral marine population was and continues to be maintained by recurrent gene flow from existing freshwater populations. Gene flow from freshwater populations provides a better explanation for the maintenance of low-armor alleles than mutation-selection-drift balance in the sea because recurrent mutation would generate many novel freshwater alleles at each locus, whereas very few origins of the freshwater Eda and Kitlg alleles are indicated (Fig. 3.4B and C).

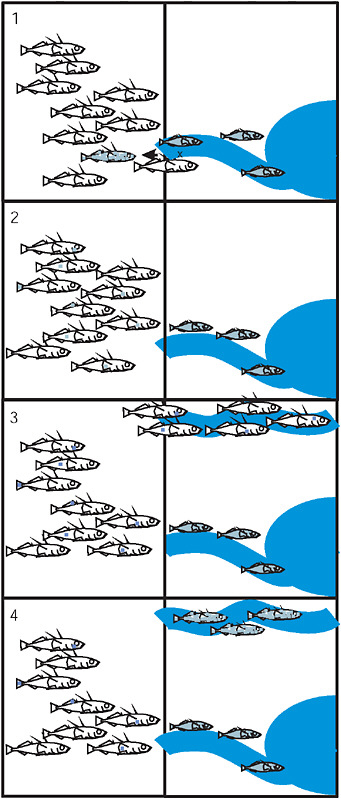

Our “transporter”* hypothesis is founded on what we know already about Eda and Kitlg and adds what we suspect regarding the source of standing variation in the marine population. In the first step of the trans-

porter process (Fig. 3.5), alleles from a stream-adapted population are exported to the sea by a hybridization event between individuals from the marine and stream populations. Multiple generations of recombination cause the disintegration of the freshwater-adapted genotype, such that each member of the marine population carries 0, 1, or only a small number of freshwater-adapted alleles. In the third step, a new stream is formed elsewhere, such as at the front of a receding glacier, and is colonized by the marine species, which brings standing genetic variation from the sea. In the last step, selection with recombination increases the frequency of freshwater-adapted alleles in the new location, gradually reassembling the freshwater-adapted genotype at a new site (Fig. 3.5). This transporter process is a special case of the broad view that hybridization is a creative force in evolution and diversification (Arnold, 1992; Rieseberg, 1997; Seehausen, 2004). In our model, gene flow facilitates multitrait parallel evolution and speciation on a large geographic scale. The hypothesis does not address where or when an advantageous mutation arose, but proposes that once a mutation reaches appreciable frequency in a freshwater population it could participate in the transporter process.

A key assumption of this transporter hypothesis is that existing freshwater populations are the source of standing genetic variation in the marine ancestral population. Existing data allow a preliminary test. The most likely sources of alleles present as standing variation in a given marine population are nearby freshwater populations, because the freshwater-adapted alleles are presumably selected against in the sea, which will shorten the distance that an allele copy can disperse before it is eliminated by selection. It follows that the source of freshwater-adapted alleles brought by the marine species when it colonized a new stream is most likely to have been close by. To test this idea we examined the similarity of the DNA sequences of low alleles at the Eda locus between nearby freshwater populations compared with that between more distant freshwater populations (Fig. 3.6). We confined our attention to freshwater populations in the Pacific basin, because there is currently no dispersal route for stickleback between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Fig. 3.6 displays the

FIGURE 3.5 The 4 stages of the transporter process: (1) Hybridization between the marine and derived freshwater population exports freshwater alleles to the sea. (2) Recombination in the marine population breaks apart the freshwater combination of alleles. Each allele is now present as rare standing variation in the sea. (3) Colonization of a new freshwater environment by marine fish brings along standing variation. (4) Selection with recombination in the new freshwater population drives the freshwater-adapted alleles to high frequency and reassembles the freshwater genotype. In each panel the vertical line separates the ocean from terrestrial environments containing streams that drain into the sea.

FIGURE 3.6 Multidimensional scaling (MDS) of low-armor Eda sequences from different freshwater populations (Upper) and of high-armor Eda sequences from marine populations (Lower), all within the Pacific basin. Axes are scaled so that magnitudes are comparable in both plots and along both axes.

SOURCE: Data are from Colosimo et al. (2005).

results of a multidimensional scaling analysis (R Development Core Team, 2008) based on pairwise percentage sequence similarity between populations in 1,328 bp of the Eda gene (Colosimo et al., 2005). Points next to one another indicate populations that have similar Eda sequences, whereas points far apart indicate populations with more different Eda sequences. The findings reveal that indeed nearby freshwater populations have similar low-armor alleles at the Eda locus. This result is confirmed by a high Mantel correlation between percentage sequence divergence and geographic distance (z = 0.97, P = 0.002). This similarity cannot be explained as the result of direct gene flow between the populations because they have always been isolated from one another by the sea. Instead, we attribute the similarity of Eda alleles between nearby populations to the transport of low alleles from one population to the other by a process that included an intermediate stage during which alleles exported from freshwater were present as standing variation in the marine population. Such a transport process may continue today in moving allele copies between freshwater populations that still hybridize with marine populations.

The strong biogeographic pattern seen in freshwater-adapted low-armor Eda alleles contrasts strikingly with the absence of geographic structure in the high-armor Eda alleles found in contemporary marine popula-

tions (Fig. 3.6). Absence of geographic structure in high-armor Eda alleles is associated with a low overall level of sequence heterogeneity, suggesting that the marine populations of the Pacific are well mixed compared with freshwater populations (Fig. 3.6). Such mixing would also be expected to eliminate any geographic pattern in the sequences of low Eda alleles present as standing variation in the sea. The presence of geographic structure in freshwater implies that standing variation for low-armor alleles in the sea was also structured biogeographically at the time of colonization. The most likely cause of such structure in an otherwise well-mixed sea would have been continuous replenishment from nearby freshwater sources as proposed in the transporter hypothesis.

This transporter hypothesis helps to explain the parallel evolution of premating reproductive isolation in widely distant freshwater populations (McKinnon et al., 2004). Further tests are warranted aimed at distinguishing this hypothesis from the alternative hypothesis that speciation is the result of new mutations that occurred in freshwater populations after colonization (or in the sea immediately before colonization). Both hypotheses make the same prediction regarding expected phylogenetic histories of neutral markers, namely that the alleles present in freshwater populations should be descended from alleles present in nearby marine populations (e.g., Fig. 3.4A). If selected genes arose by new mutation after (or immediately before) freshwater colonization, then they should show a similar history to that of neutral markers. However, under the transporter process, genes underlying reproductive isolation in freshwater populations were positively selected from standing variation maintained in the sea, in which case the genes should be most closely related to gene copies found in other freshwater populations nearby. Further tests await the discovery of genes underlying reproductive isolation.

CONCLUSIONS

Ecological speciation differs conspicuously from the mutation-order speciation by the pattern of selection on genes. Under ecological speciation, alleles at diverging loci are favored in the environment of one population but not that of the other. In contrast, under the mutation-order process the same alleles are favored in both populations, at least initially; yet by chance each allele arises and fixes in just one of them. An immediate consequence is that ecologically based prezygotic and postzygotic isolation should evolve only under ecological speciation. In contrast, the buildup of intrinsic postzygotic isolation by incompatible side-effects of selected loci can occur under either mechanism (Barton, 2001). Under the right conditions both mechanisms would leave a signature of positive selection at the molecular level, and it is difficult to think of an easy way

to discriminate ecological from mutation-order speciation solely from examination of features of the underlying genes.

Evidence from laboratory experiments and field studies suggests that reproductive isolation accumulates more rapidly between populations adapting to different environments (ecological speciation) than between populations adapting to similar environments (potentially, mutation-order speciation). This difference might have a genetic explanation. There is a higher probability that the same or equivalent mutations will fix under parallel selection than under divergent selection, which will slow the rate of divergence between populations experiencing similar selection pressures. Alternatively, divergent selection may simply act on more genes.

Other genetic processes during ecological speciation become apparent when there is gene flow between populations, either continuously during their divergence or after secondary contact. With significant gene flow, premating isolation is unlikely to arise or persist unless the genes underlying it somehow overcome the antagonism between selection and recombination, such as by pleiotropy or by reduced recombination with genes under divergent natural selection. No such genetic features are predicted for premating isolation under either ecological or mutation-order speciation in the absence of gene flow.

Finally, for similar reasons the role of standing genetic variation in speciation is likely to be greater under ecological speciation than under mutation-order speciation. Selection from standing variation will increase the chances that separate populations experiencing similar selection pressures will fix the same rather than different alleles, inhibiting divergence. The repetitive origin of species under the transporter process proposed herein seems possible only under ecological speciation. The reason is that while a derived population with a distinct set of strongly interacting alleles built under a mutation-order process and conferring significant reproductive isolation can persist after secondary contact in the face of some gene flow with an ancestral population (Barton, 2001), the export of individual alleles will be resisted by these same interactions. Individual alleles that succeed in spreading to the ancestral population may be favored there, in which case differentiation at the locus will be eliminated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Avise and F. Ayala for their kind invitation; J. Avise, R. Barrett, P. Nosil, S. Via, and another reviewer for helpful comments on the manuscript; and P. Colosimo (Stanford University) and D. Kingsley (Stanford University) for the Eda sequences. Research in D.S.’s laboratory is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (Canada) and the Canada Foundation for Innovation.