2

The Dual Crises: Tandem Threats to Nutrition

Three of the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), adopted in 2000 by the member states of the United Nations and the world’s major development institutions, are closely linked to malnutrition in young children and in women: eradicate extreme poverty and hunger (MDG 1), reduce child mortality (MDG 4), and improve maternal health (MDG 5). A strong evidence base underpinning and motivating further investment in nutrition has emerged over the past 5 years. Specifically, a Lancet series, published in January 2008, showed that maternal and child undernutrition is the underlying cause of 3.5 million deaths annually, 35 percent of the disease burden in children younger than 5 years, and 11 percent of total global disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) (Black et al., 2008). With this evidence as a foundation, it seemed that if the will, the tools, and the technologies had all been mobilized, then real progress in nutrition could be made. Then the recent abrupt increases in global food prices, exacerbated by the current global economic downturn, began to threaten the hoped-for trajectory of progress. Between March 2007 and March 2008, price increases of 31 percent for corn, 74 percent for rice, 87 percent for soya, and 130 percent for wheat were documented (Hawtin, 2008). This chapter looks at the contributing factors and potential causes of the recent food price hikes and the current global economic downturn. As described by planning committee chair and session moderator, Reynaldo Martorell of Emory University, the following presentations helped to set the stage for the deliberations by having an overview of the recent food price crisis and how it, in tandem with the current economic crisis, affects developing countries.

THE RECENT AND CURRENT FOOD PRICE CRISIS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Per Pinstrup-Andersen, Ph.D.,

H.E. Babcock Professor of Food and Nutrition Policy

Cornell University

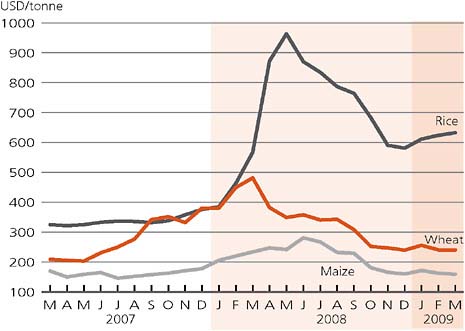

The “global food crisis” is often thought of as a crisis that came and went. In reality, this is a crisis that came but never went away. Until the beginning of this century, there had been a tremendous decrease in the real prices of food (the food price relative to other prices). Dramatic increases in food prices were seen during the past 2 to 4 years, up until the middle of 2008. Since then, prices began to fall, and they fell quite dramatically during the subsequent year, between the middle of 2008 until April or May of 2009. Yet the food crisis is far from over. Food prices are still considerably higher than they were 5 or 6 years ago. From a poverty and nutrition perspective, the fluctuation of the prices—or the price volatility—has the most significant impact (Figure 2-1). These fluctuations have led to an unstable nutritional environment, especially for the world’s poor.

Causes of Food Price Fluctuations

A number of factors, specifically supply side, demand side, market, and public and private action, caused the prices of food to fluctuate. On the supply side these included adverse weather, rapidly falling prices (1974–2000), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)1 production subsidies, and limited agricultural investments. On the demand side, these factors included biofuel production, increased demand for meat and dairy products, increased feed demand, economic growth in middle-income countries, and economic recession. The market factors included low and falling stock levels, capital market transfers (capital invested into commodity futures), changing dollar value, and increasing oil and fertilizer prices. The public and private action factors included export bans and restrictions, panic buying, reduced import tariffs, price controls, rationing, food riots, hoarding, and media frenzy.

Supply Factors

A variety of supply factors affected price fluctuations. Changes in weather, especially short-term droughts, had a large impact on wheat producers in Australia, Ukraine, and parts of the United States. Droughts reduced production, which increased wheat prices. The rapidly falling prices that occurred after the

FIGURE 2-1 Selected international cereal prices.

NOTE: Prices refer to monthly average. For March 2009, 2 weeks average.

SOURCE: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2009b.

1974 price hike also affected the current food crisis. When prices continue to fall, little investment is made in rural areas and in agriculture. Therefore, agriculture productivity does not increase as fast as it should, production does not keep up with demand, and eventually prices begin to increase. In OECD countries, production-expanding subsidies were maintained, and more food was produced than the markets could bear at the higher prices. However, the products were dumped into the international market and even developing country markets, creating a very unfair advantage for the OECD countries and resulting in the depression of prices.

Demand Factors

When the prices of energy and oil rose, the United States, European Union, and a number of other countries turned to the use of food commodities to create biofuels. This increase in demand resulted in the pulling away of food commodities from the food market. Supply reduced, and food prices rose. Institutions’

opinions as to how great an impact the use of biofuels had on the rapid price increase are usually in line with what the institution’s economic interests are (some claim a 30 percent impact, others a 3 to 4 percent impact). Therefore, the extent to which biofuels increase food prices is unknown, but it is certain that biofuels had some effect.

While food prices were dropping, rapidly growing middle-income and high-income countries, such as China, increased their demands for meat and dairy. This put more pressure on the need for livestock feed, taking food away from the food market and causing prices to rise. Economic growth also contributed to an increase in the food demand. When the economic recession hit, however, prices came down again.

Market Factors

There were also various market factors contributing to the rapid increase in food prices. Stock levels, especially of grain, were very low from 1998 onwards. This added to concern that there would be price increases. Additionally, there was quite a bit of capital made available as part of the housing market problems and other financial crises-related issues in the United States and elsewhere. Much of that capital went into commodity futures. Oil prices were going up, food prices were beginning to go up, and people with money to invest decided commodity futures was a good place to put money. This phenomenon pushed up prices far beyond what the supply and demand called for. Later, when the capital was pulled out, there was a dramatic drop in prices, at least partly caused by this capital flowing out of the futures market.

Increasing oil prices pulled the prices of fertilizer and pesticides up as well, since oil is needed for the production of those commodities (in particular, nitrogen fertilizers). Fertilizer prices increased faster than the food prices and were much slower to come down after food prices began to decrease. Many farmers in Denmark, for example, were told in August and September 2008 that there was going to be a short supply of fertilizer for use in March and April 2009, and that they should buy fertilizer despite the high prices. Though farmers expected grain prices to remain high, they fell instead.

Yet another market factor for the food price increase was the depreciation of the U.S. dollar. Food prices are usually expressed in dollars; when the dollar became weak at the beginning of this century, food prices rose wherever they were expressed in dollars.

Public and Private Action Factors

Public and private behaviors also caused this rapid increase in food prices. Export bans and restrictions, particularly in the rice market, had an especially large impact. When wheat prices began to rise (due to drought, increase in

biofuel production, and other reasons), the Indian government decided to stop exporting rice in order to protect itself and keep the rice price down, hoping to see a substitution between the higher-priced wheat and the lower-priced rice. This caused the rice price in the international market to increase dramatically. Other countries, such as Vietnam, Cambodia, and China, decided to follow India’s lead in order to protect their own consumers. This is “bad neighbor policy,” for the government sees its legitimacy and population as being threatened, and therefore has no concern about the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the rest of the world. Later, India and Vietnam continued to restrict exports, but gave political favors by allowing some select countries to purchase their rice. The United States, Thailand, and a few other countries decided to risk continued rice exporting; these “good neighbor policies” (though they were driven by self-interest) were the saving grace in the rice export market.

Reduced import tariffs also played a role in the rapid price increase. Countries put import tariffs on food to generate public revenue, but they began to take away the tariffs when international prices went up. The WTO did not have power over these policies so was unable to intervene. Countries faced with higher food prices put in place such things as price controls and food rationing. Households, and even governments, began to hoard food since they expected food prices to rise. In addition, there were food riots in up to 60 countries. These riots are not instigated by poor rural people whose children are dying from hunger and malnutrition, but rather by lower-income urban consumers who do not like paying more for food. The governments only respond to those who pose a threat to the government; therefore, no attention was paid to the people in the rural areas. This is why price controls, rationing, and input tariff reductions were put in place only in urban areas.

There was also a media frenzy surrounding the food crisis. When food prices went up, the food crisis was on the front page of virtually every newspaper in the world. However, as soon as food prices began to fall, the media stopped producing articles about the issues. This frenzy contributed to some of the panic and hoarding that happened after food prices began to rise. Even in the United States, some retail chains rationed rice for a short period of time.

Impact of Food Price Fluctuations

Factors that determine the impact of food prices at the household level include:

-

Price transmission,

-

Whether the household is a net buyer or net seller,

-

Household budget share for food,

-

Extent of value addition,

-

Relative price changes among diet components,

-

Relative price elasticities, and

-

Risk management capacity.

The impact of food price fluctuations depends on the price transmission, or how the international market transmits prices to the country, household, and ultimately, to the individual. For example, consumers in India and China did not see much change in the rice price because the policies their governments had in place prevented consumers from being affected. These same policies, though, hurt others in the international community; for instance, they caused consumers in the Philippines to be greatly affected by rice prices. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), although prices have come down, many low-income, developing countries are still feeling the effects of the food price spikes (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2009a). For example, in Kenya, the price for maize continued to increase as the international prices for maize decreased. Therefore, it is important to remember that there is not a direct link between global trade policies and the prices that poor people are faced with in developing countries.

Another factor that determines the impact of food prices on a household is whether the household is a net buyer or net seller. A large percentage of small farmers in developing countries are net buyers of food and therefore suffer short-term negative effects from food price increases. Organizations such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation are trying to reach farmers with agricultural investments to help them become net sellers instead of net buyers. Once households overcome that threshold, they can benefit from higher food prices.

The impacts of the price increases also depend on the household budget share for food. Poor people spend 50 to 70 percent of their income on food. High-income people, on the other hand, spend 5 to 10 percent (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank, 2007). Furthermore, people in high-income countries spend a larger share of their consumer dollar on post-harvest additions to food, while poor country consumers’ dollars go largely to pay for the food itself. Nutrition of the poor, then, is clearly much more affected by food price fluctuations. The relative price range among diet components can have very serious nutrition implications. If one particular food price goes up faster than another, households adjust to the change.

Finally, the effects of the food price fluctuations greatly depend on risk management capacity, which is very low among the poor. High-income people can utilize savings or cut back on luxury spending in times of crisis, whereas low-income people have to take much more drastic measures to adjust to the changes in price.

Policy Response to Food Price Increases: The Movement Toward Food Self-Sufficiency

Policy responses to the food price increases include expanding food production, moving toward self-sufficiency, and maintaining government legitimacy. Expanding food production has resulted in a renewed interest in national self-sufficiency and an increased interest in reserve stocks and the acquisition or control of land across borders. The move toward food self-sufficiency has built up global grain stocks, enhanced control over land in foreign countries, and increased the impetus toward a build-up of financial reserves. Efforts to maintain government legitimacy often emphasize such short-term measures as price controls, export bans, lifting import tariffs, rationing, and food distribution. Other efforts to maintain government legitimacy emphasize short-term transfers to the urban lower-middle class, which result in the continued neglect of the rural poor.

Governments can take a variety of positive steps, such as investing in rural areas, increasing productivity, funding agricultural research, and developing agricultural infrastructure. These allow farmers to produce more and increase their income so that they can finally escape poverty. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has been supportive in helping farmers achieve this goal. These policy responses are positive ways that governments can gain more control over food price fluctuations.

Negative steps have also been taken. Governments are motivated to stay in power, which requires national support. This desire to maintain legitimacy when food prices began to increase led to price controls, export bans, reduced import tariffs, rationing, and food distribution. These governments emphasized short-term solutions that only addressed the unsatisfied and vocal urban lower-middle class, so as to diminish the threat this group posed to the government. These policies neglected the rural poor, who are continually ignored and malnourished.

Some governments expanded food production, showing a renewed interest in achieving national self-sufficiency. Food self-sufficiency is a dangerous idea that negatively affects the international community. Governments are rapidly building up reserve stocks to try to protect themselves from the untrustworthy international trade market. Additionally, some governments are trying to take control over land outside of their own country, often termed “land-grabbing.” This might occur when middle-income countries move in to lower-income countries and attempt to gain control of large extensions of land and the crops that are produced on that land.

Ideally, countries need to focus their energies on building financial reserves in order to handle price volatilities. However, the economic crisis has made it difficult for countries to build such reserves.

Future Perspectives

What will happen in the future can be affected by a number of factors, including

-

A significant supply response,

-

Falling real food prices,

-

Increasing price volatility,

-

Strong links between oil and food prices,

-

Continued urban bias in policy interventions,

-

Return to government complacency, and

-

$20 billion from the G8 that could dramatically increase food production and decrease poverty, hunger, and malnutrition.

When prices change, there is a significant supply response. For example, in response to price increases, farmers produce more food. Alternatively, when prices drop, farmers decrease the amount of food they produce. Lower-income farmers may not have the opportunity to expand and contract their production in response to the market, due to poor infrastructure, lack of available Green Revolution technologies, inability to get credit, and nonfunctioning markets. It is important to focus on the unique situation of those in low-income countries when trying to mitigate the impacts of food price increases.

Prices are eventually going to decrease, due to the large amount of food that will be released into the market over the next few years. Countries that have export bans will eventually have to open their doors for exports because they will be internally flooded with extremely high amounts of rice and grain stock.

An increase in price volatility in the future is highly likely because of climate change (more severe droughts and floods) as well as national efforts to become food self-sufficient. Attempts to be self-sufficient will cause increased food production where it should not necessarily be produced, while disincentivizing food production where it is most efficiently produced.

The strong links between oil and food prices may lead to a reconsideration of biofuel policies. Currently, without subsidies, it is not profitable to produce biofuels from corn. With higher food prices, there will likely be more investment in agricultural productivity. It would be ideal if developing country governments prioritize agricultural development and productivity increases. This is possible; the world is not running out of productive capacity. Yet, governments should not intervene in such a way that prices become skewed; that will affect not only economic efficiency, but also either producers, consumers, or both.

In the future, there will likely be a continued urban bias in policy interventions, owing to threats such as food riots that the urban poor pose against governments. The return to government complacency is a real danger to the health and nutrition of those most affected by the global food price crisis. Ideally, if the $20

billion that came out of the L’Aquila G8 summit in Italy is used effectively, there will be a dramatic increase in food production in Africa and a dramatic decrease in poverty, hunger, and malnutrition.

THE CURRENT GLOBAL ECONOMIC CRISIS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Hans Timmer, Director of the Development Prospects Group

The World Bank

The world is encountering a major global financial and economic crisis that has taken a heavy toll on private capital flows to developing countries. The financial crisis was sudden, global, and unprecedented. In September 2008, the world suddenly changed. Because of different policy reactions to this financial crisis, including aggressive stimuli by governments and severe reactions by monetary authorities, the World Bank predicts that the total crisis will not be as dire as the Great Depression of the early 1930s. International policy responses helped stabilize financial and commodity markets and stopped the “free fall” in trade and production. As a result of appropriate policy reactions, the worst of the collapse in the global economy is likely over. More worrisome, though, is the idea that this crisis—even if it lasts only a short time—is so deep that it will take several years to resolve. Coordination is needed to achieve true global recovery from the problems that many developing countries, in particular, are facing at the moment.

Impact on Developing Country Economies

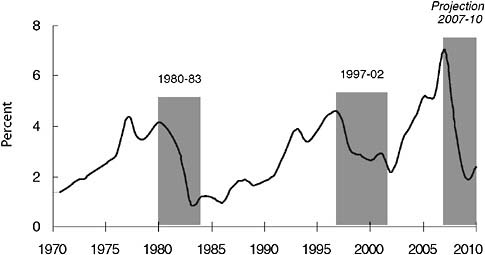

The first mechanism through which developing countries were affected by this crisis was when, because of an increase in uncertainty, anxiety, and panic, financial markets saw a sudden drying up of credit. For example, the failure of Lehman Brothers had consequences that reached all over the world. As a result of the failure of big financial institutions in the United States, suddenly these institutions began to withdraw their overseas investments. Over the past several years, such investments had, to a large extent, gone to emerging economies. In fact, because there is strong growth potential in developing countries, there had been a boom in capital flows going to developing countries (mainly to the private sector) since the beginning of this decade. Such investments reached $1.2 trillion in 2007, dropping to around $700 billion in 2008 (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank, 2009a). The World Bank forecasts show that the capital flows going to developing countries will decrease further in 2009 to around $360 billion—a quarter of what resources were only 2 years ago (from 8 percent to 2 percent of gross domestic product [GDP] of all developing countries), significantly affecting developing countries (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank, 2009a) (Figure 2-2).

FIGURE 2-2 Net private capital flows per GDP in developing countries.

SOURCE: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank, 2009b.

In a macroeconomic sense, as a result of the crisis, all countries are facing financing needs this year. These needs are difficult to meet because of the collapse in financial flows, especially for central and eastern European countries that currently have large account deficits (they import more than they export and must repay money borrowed in previous years). In total, developing countries need some $1.1 trillion this year to repay former or finance current account deficits (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the World Bank, 2009b). Developing countries need support from international financial institutions to weather the storm of the financial crisis.

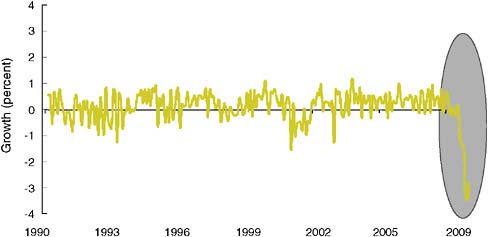

The World Bank gathers data from approximately 150 countries in the world and each month calculates the “heartbeat of the global economy”—or the growth of global industrial production. The recession after the burst of the dot-com bubble in 2000 and 2001 had global proportions. It is also notable that since that time, the world economy has experienced a period of very stable, strong growth. Developing countries especially performed very strongly over the past 5 years, but starting in September 2008, the points fall off the chart (Figure 2-3). Within 5 months, the world economy lost more than 15 percent of global industrial production (as much as was accumulated in the 4 years before September 2008). Global trade also experienced a similar, sudden decline.

In an attempt to determine the ingredients of a global recovery, it is important to understand the relation between this global decline in production and the global decline in trade, as well as the global decline in commodity prices. In the period of 5 months starting in September 2008, all commodity prices (including food

FIGURE 2-3 Rapid decline in global industrial production.

SOURCE: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank, 2009a.

and oil prices) fell between 40 and 50 percent (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank, 2009a, 2009b).

A common explanation of the global economic downturn assumes the world’s dependence on the U.S. economy. According to this explanation, the crisis in the United States caused all developing countries that exported to the United States to feel the negative effects; as a result, the whole world economy is in a recession, and what is needed is large stimulus in the United States. The U.S. consumer needs to spend again, which will allow the rest of the world to recover. In the World Bank’s view, this is the wrong story.

Instead, the World Bank’s assessment is that, as a result of the financial crisis in the United States, all developing countries were affected in their domestic economies. Because of the withdrawal of capital flows and the global panic in financial markets, investors in developing countries stopped investing, and consumers in developing countries stopped purchasing. Within a month after September 2008, the car sales in India, South Africa, and even in China were 15–20 percent below the previous year’s sales. This investment and consumer process is actually what impacted the global economy during the past 5 years.

Evidence for this explanation is seen in the import and export demand in the United States at the end of 2006. At that time, housing prices in the United States stopped increasing, and then started falling in the beginning of 2007. In the middle of 2007, housing prices fell at double-digit rates; the United States already had a financial crisis, but it was localized in the United States. As a result, U.S. consumers did not increase their consumption, and imports did not grow.

During this period, the developing world grew 8.1 percent—record growth in an historical perspective. Because of the financial crisis in the United States, U.S. exports declined. In developing countries between August 2008 and March 2009, the decline in imports was actually larger than the decline in exports. The cause of the financial crisis in the developing world, then, was not that they couldn’t export to the U.S. market, but instead that their own domestic economies stopped functioning.

Thus, what is needed for a global recovery is recovery in the investment process in developing countries. Emphasis must be placed on coordinated stimuli that help developing countries restore their equilibrium so they can grow again.

Future Perspectives

By the end of 2009, a contraction of almost 4 percent of global GDP is expected. To a large extent this has been caused by the economic decline in high-income countries that face both domestic economic problems and reduced exports. On average, developing countries are still growing; a 1.2 percent growth is expected in 2009 (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank, 2009b). However, if India and China are removed from the list of developing countries, there would be a decline of 1.7 percent (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank, 2009b).

Because of the stabilization of the market and the myriad endogenous mechanisms that exist with a crisis like this, the World Bank predicts that the world will recover and even see 2 percent growth this year. Despite this percentage of recovery, at the end of 2010 there will still be less income being generated in the world than at the end of 2008. During these 2 years, the global economy will have lost income, which is unprecedented in the recorded history of the world.

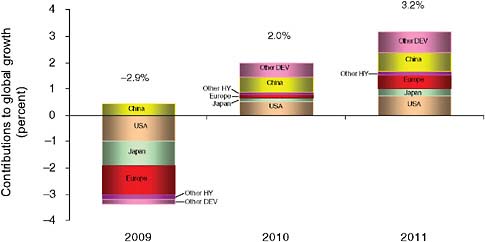

In terms of the contribution to growth, the World Bank estimates that in 2010, more than one-half of growth will originate in developing countries, and half of that will be from China. This prediction is consistent with the performance of the world economy during the past 5 years. Developing countries contribute roughly one-quarter of the world economy, but over the past 5 to 7 years, their growth rate was on average 2.5 times the growth rates of high-income countries. In terms of contribution to growth, then, developing countries are already more important than high-income countries. It follows that the focus on where to stabilize the world economy should be in developing countries (Figure 2-4).

Despite the fact that recovery is predicted, the severity of the problems to be tackled—global underutilization of capacity, idle factories, and unemployment—may continue to increase. For example, unemployment will further increase in most countries next year and even in 2011.

FIGURE 2-4 United States, China, and developing countries lead upturn.

NOTE: Other DEV = Other Developing; Other HY = Other High Income.

SOURCE: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank, 2009b.

Conclusions

First, while recent market indicators show stabilization, much remains to be done to place global finance on a stable footing. The global economic recession is a problem for governments that will require international support and coordination.

Second, protecting the growth prospects of developing countries serves the interest of rich countries as well. Major reforms in the developing world were seen during the 1990s that led to strong growth in many countries. It is not coincidental that the economic crisis did not start in countries with these emerging economies, but rather it began in high-income countries. There is still a great deal of potential in emerging economies, but they have been adversely affected by the crisis and need help to restore their economies.

Finally, the global nature of the crisis places a premium on policy coordination in order to prevent new crises and ensure balanced global growth. The current economic problems are occurring on such a large scale that no individual country can solve them on its own. International coordination should focus on two things: preventing new crises from developing and recovering growth in a balanced way that doesn’t re-create the imbalances that contributed to the current crisis.

DISCUSSION

This discussion section encompasses the question-and-answer sessions that followed the presentations summarized in this chapter. Workshop participants’ questions and comments have been consolidated under general headings.

Impact of the Crises on Poverty

The World Bank analyzed the impact of the economic downturn on poverty levels and determined that because of the crisis, up to 100 million people were pushed back into poverty (defined as living on less than $1.15 a day) or were not able to come out of severe poverty (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank, 2009). Although the poor are always the most vulnerable and it is always difficult for them to absorb shocks of any kind, the current economic crisis is actually one that does not necessarily impact the poor disproportionately. The economic shock decreases the value of assets and, therefore, affects the middle class in developing countries more than the extremely poor who have few assets. (Food prices, on the other hand, more than proportionately affect the poor.)

Impact of the Economic Crisis in Sub-Saharan Africa

The World Bank’s first impression was that sub-Saharan African countries would be less affected by the financial crisis because they are not very integrated into global financial markets. It was later realized that the impact was large in many African countries because a large number of the investments in the mining sector were public–private partnerships. The private part of these partnerships ceased activity as private investors were hesitant, and they either postponed or cancelled their investments because of the financial crisis or the uncertainty in commodity prices.

More importantly, Africa is threatened by a political backlash. The reforms in Africa are much more recent than in many other parts of the developing world. Only recently did many sub-Saharan countries open their borders and invite foreign investors to come in. In Africa, this had a positive effect, and sub-Saharan Africa saw growth of 5–6 percent after decades of per capita income declines. The fear is that African national governments or opposition parties will now be reluctant to rely on international markets as a result of the crisis, and they will attempt to remain self-reliant.

Temporality of Food Price Spikes and Economic Downturn

The spike in food prices occurred in June and July 2008; the global economy dropped in the fall of 2008. Is there a temporal connection to be drawn between the two? In fact, what happened in the food markets is very consistent with what

happened in other commodity markets, which is, in turn, very consistent with what happened in the global economy. The spike in food prices in mid-2008 can be explained by the fact that growth in the world economy was extremely strong. As a result, oil prices were very high. The link between oil prices and the food market is relatively new. What happened after September 2008 is exactly the reverse—a decline in global production. Demand for oil declined by 3.5 million barrels a day. Oil production decreased and oil prices came down, which brought down other prices.

Speculation

What role does speculation play in the food commodities market? Is there a way to regulate that type of commodity speculation when it comes to food staples? Should there be regulation of that kind? The World Bank does not believe that the financial markets were the cause of the swings in the food prices or in commodity prices in general. In addition, the World Bank does not believe that the financial markets were the cause of the sharp increase that was seen in the middle of 2008, and it is believed financial markets were not the cause of the downturn. What is very likely is that financial markets exacerbated some of the movement that was seen; it might be possible that the decline in food prices and commodity prices since the start of the crisis (that would have occurred anyway) occurred earlier and more quickly because of the working of financial markets.

It is not easy to regulate without damaging some of the advantages of financial markets—smoothing out behavior and giving either producers or consumers the opportunity to hedge the risks that they have to make. Even without financial markets there would have been large price swings. In fact, in several metal markets, the same kind of price behavior occurred though there were no financial instruments at work with those metals. It is easy to overestimate the importance of the financial markets.

Diet Diversity More Important Than Energy Consumption

There was a concern, voiced by Dr. Ricardo Uauy, that when food production is discussed, the conversation is only about cereals, and hunger should not be defined by energy or calorie intake alone; both diet diversity and the nutrient and micronutrient densities of diets are important in influencing nutritional health of populations. Food quality is what is important for nutritional well-being, and “hunger” should no longer be based on energy alone. The assumption that sufficient caloric intake for energy is all that matters has been misguided, and the global community is now paying the price of that. Diet diversity is what the international nutrition community needs to be concerned about. Statistics from FAO are still focused on calories and protein; a change in favor of empirical evidence on diet diversity and the intake of micronutrients would be an improvement.

Agricultural Foreign Direct Investment in Africa

The issue of foreign direct investment in Africa is controversial. While investing in agricultural productivity and the infrastructure needed to support it can contribute in positive ways, there are differing views on the process. Much of the effort that is taking place in this area is between two country governments, or between a private corporation outside the country and a government within the country. The risk of having that kind of negotiation is that small farmers who are currently on the land are being ignored; when these agreements are made, the farmers are often pushed off their land. If, instead, the agreements were made in negotiation with the farmers who are currently on the land, and if investment in rural infrastructure came along with such agreements, this type of agricultural foreign direct investment would have positive effects.

Trends in Development Assistance

Certain financial flows to developing countries are more resilient than other flows. For example, the flow of remittances (transfer of money by foreign workers to their home countries) is very resilient (and amounts this year to more than $300 billion to developing countries, which is almost as much as the private capital flows to developing countries and more than official aid to developing countries). The World Bank does expect a decline in that flow as a result of the labor market problems in countries of destination for migrants, but less so than is predicted in other flows to developing countries. Official aid, including philanthropies, is also a relatively stable source of growth. Financial flows coming from the World Bank are almost countercyclical in that the Bank is currently tripling its lending to developing countries.

Food Price Reasonableness

What constitutes “food price reasonableness,” and how can it be measured? A reasonable food price is a function of productivity in agriculture and a function of people’s purchasing power. There is no way to have a definition that declares the price of commodities without taking these variables into account; it is a very slippery concept. It is much easier to identify unreasonable prices than reasonable prices.

Sustainable Management of Natural Resources

Poverty, in many cases, creates unsustainable management of natural resources. If poverty can be reduced, particularly in rural areas, improved sustainable management of natural resources will follow. If rural people can be helped out of poverty, it is very possible that the sustainability in natural resource

management can be increased. There is a misguided sentiment that if you increase productivity and agriculture is increased, natural resources are harmed. This is not necessarily so (Nkonya et al., 2008).

Investment in Human Capital

A significant proportion of recent economic growth has been the result of growth in developing countries. Some people in the nutrition and health field link that growth to investment in human capital. When discussing financial flows and eventual recovery strategies as part of the mitigation policy, is there any effort being made to preserve or continue the investment in human capital? Several workshop participants agreed that the international effort should not combat this crisis by merely spending money to create jobs in the short run. Instead, the focus should be on government interventions that help maintain or further increase productivity in preparation for the rebound. It is very important that government spending focuses on the long run, including investments in human capital.

Reliable Data for Early Warning in Africa

Obtaining reliable and current data from Africa is an ongoing challenge. This creates a big problem for timely response to crises. National governments’ capacities to generate reliable data needs to be strengthened. The World Bank has a data group, and one of its missions is building capacity in developing countries, mainly in Africa. There is cooperation with governments and various institutes in improved data analysis, compilation, survey management, and organization.

Beyond direct data collection and analysis, there are indirect ways of trying to understand the impact of the crisis, such as watching the international markets and making comparisons with other countries. A degree of creativity may also be needed when working with early warning systems. Some workshop participants argued that, in some situations, although the hard data do not exist, action can and should be taken. It is not always prudent to wait until perfect data collection exists in all countries.

The World Bank Response

In responding to the food price crisis, the World Bank focused on three areas, starting with safety nets. A safety net refers to the institutions through which targeted transfers to those who need help most can be facilitated. The focus is much more on institutions than on money.

The second area the World Bank has focused on is investment, especially in Africa. If a very long-term view is taken, the problem is not that the world is running out of food. There is, instead, a continuous increase in the production of food and, in particular, meat. The problem is that there are regions where the

demand is relatively high and the supply growth is lacking. Africa is the perfect example of that. Decades ago, Africa was a food exporter; it is now one of the largest food importers. A solution to the global food crisis, then, is to increase productivity in Africa.

The third area of focus for the World Bank was an attempt to stabilize prices through international government intervention in stock keeping and regulation of financial markets. After much debate, though, the Bank decided that such efforts have always failed, been ineffective, and turned into price subsidies and price management.

Effects of the Crisis on Geopolitics

Every major crisis changes the world in some lasting way. After this crisis, the world will be never the same because the role of developing countries will be much larger than it was before. Additionally, the very dominant position of the United States in financial markets and international policy making will be diminished somewhat, and the role of other countries—especially in Asia—will increase. The G20 is already more important than the G8 in many policy discussions, part of a growing trend toward increasing the voice of developing countries.

REFERENCES

Black, R. E., L. H. Allen, Z. A. Bhutta, L. E. Caulfield, M. de Onis, M. Ezzati, C. Mathers, and J. Rivera. 2008. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet 371(9608):243-260.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2009a. “Global Information and Early Warning System.” Retrieved September 3, 2009, from http://www.fao.org/giews/english/index.htm.

———. 2009b. “GIEWS International Cereal Prices.” Retrieved September 3, 2009, from http://www.fao.org/giews/english/ewi/cerealprice/2.htm.

Hawtin, G. 2008. CIAT’s Response to the World Food Situation. Cali, Columbia: CIAT.

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank. 2007. World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

———. 2009a. Global Development Finance 2009: Charting a Global Recovery. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

———. 2009b. Global Economic Monitor. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

New Challenges Emerge at Millennium Development Goals’ Half-Way Point. 2009. Retrieved November 3, 2009, from http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/NEWS/0,,contentMDK:21914817~pagePK:64257043~piPK:437376~theSitePK:4607,00.html.

Nkonya, E., et al. 2008. Linkages between Land Management, Land Degradation, and Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Uganda. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.