7

U.S. Policy in Food and Nutrition

The U.S. government can play an important role in the fight to end global hunger, and there is a renewed sense of political will to address these issues. This chapter covers what is being done to reorient U.S. policy in food and nutrition from the perspectives of the Roadmap to End Global Hunger, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Chicago Initiative on Global Development. As described by moderator Jackie Judd of the Kaiser Family Foundation, the following presenters discussed what the U.S. government can and should do to help avoid future food crises and mitigate the negative nutritional effects of those that cannot be avoided.

THE ROADMAP TO END GLOBAL HUNGER

James McGovern, B.A., M.P.A.,

Representative for Massachusetts’ 3rd Congressional District

U.S. House of Representatives

Although these are interesting and challenging times, the issue of ending hunger must take on a renewed sense of importance and urgency. The United Nations estimates that the number of hungry people in the world is over 1 billion (FAO, 2009). A statistic of this magnitude is difficult to comprehend. The number is so huge that some may lose the human ability to feel it—or some may be overwhelmed and choose to ignore the crisis. The fact is this: there are some issues that cannot be solved in this lifetime, but ending hunger is not one of them. Ending hunger can be achieved with political will. This presentation addresses

the Roadmap to End Global Hunger. It will discuss how an idea was born, how it turned into the report titled The Roadmap to End Global Hunger, and how the recommendations of that report have been translated into legislation, spearheaded by Jo Ann Emerson and James McGovern.

Background

In May 2008, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report that described why donor nations, including the United States, were failing in their efforts to help sub-Saharan African nations meet the first Millennium Development Goal of cutting hunger in half by 2015. The authors of this report, Tom Melito and Phil Thomas, briefed the cochairs of the House Hunger Caucus about the report and its findings. One of the central issues that was raised was the lack of coordination and the lack of any clear strategy about how the United States would make an effective contribution to reducing the incidence of hunger and malnutrition in sub-Saharan Africa, or work with those nations on how to create longer-term food security.

This led the House Hunger Caucus to begin discussions about the need for a specially appointed coordinator or office—or a “Hunger Czar”—to oversee a comprehensive, government-wide strategy to address global hunger and food security. This person would be responsible for helping to coordinate the often very uncoordinated food security programs on the ground. The global food crisis of 2008 put into sharp relief how many programs the United States has on food aid, nutrition, and food security and how they are spread over a variety of federal departments, agencies, and jurisdictions. The same problem exists on Capitol Hill, with global food security programs under the jurisdiction of the Agriculture, Foreign Affairs, Ways and Means, and Financial Services, to name just the principal committees.

This led Jo Ann Emerson and James McGovern to lead a crusade for a comprehensive government-wide strategy and for a coordinator on global hunger and food security. The day after he was elected President in 2008, a bipartisan letter was sent to Barack Obama from 116 members of Congress, calling for a comprehensive government-wide strategy and the appointment of a White House coordinator of such a strategy. In addition, meetings were held with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, as well as members of the Obama transition teams for the Department of State, USAID, and USDA, to discuss the importance of a comprehensive, government-wide strategy that would maximize efforts to reduce global hunger and promote nutrition and long-term food security.

In spring 2008, a diverse group of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) began talking about drafting a blueprint for the next administration on how U.S. programs and policies could more effectively and successfully address global hunger, nutrition, and food security. The NGOs had their own “jurisdictional” problems, with some focusing mainly on emergency and humanitarian relief

operations, while others were engaged in agricultural development, women and children, health and hygiene interventions, research and development, or market development; the list of their various issue, field, and regional expertise goes on and on. After months of discussion, this broad-based coalition found consensus. As a result, in February 2009 the findings and recommendations were released and presented in a report—The Roadmap to End Global Hunger.

The Roadmap to End Global Hunger

The Roadmap is noteworthy for being simple, straightforward, and brief. It recommends that U.S. government actions to alleviate global hunger and promote food security be the following:

-

Comprehensive—It must involve a government-wide effort and integrate all programs.

-

Balanced and flexible—U.S. actions must carefully balance and meet emergency needs, longer-term investments in agriculture, and safety nets for the most vulnerable, especially during this global food and financial crisis.

-

Sustainable—U.S. actions need to increase the capacity of people and governments to ultimately feed and care for themselves, reduce the impact of hunger-related shocks (whether they are natural or man-made), and be environmentally sustainable and responsive to the new challenges of climate change.

-

Accountable—The comprehensive strategy and individual programs need clear targets, benchmarks, and indicators of success. Monitoring and evaluation systems to measure and improve programs need to be developed and implemented.

-

Multilateral—Not only should the United States contribute its fair share to the multilateral efforts to address global hunger, nutrition, and food security, but its strategy should also strengthen the multilateral effort and provide international leadership.

The Roadmap recommends four basic actions to alleviate hunger and promote food security.

Create a White House Office on Global Hunger

To lead the efforts of this office, the President would appoint a global hunger coordinator. Concretely, the purpose of the office and the coordinator is to create a permanent entity to pull all related federal agencies together and design and carry out a comprehensive government-wide strategy. Equally important, this position holds the backing of the President and ensures accountability that assignments

are carried out, determines what is and is not working, what can be improved, and what needs to be eliminated—without regard to turf, budget, or other individual agency interests.

Resurrect the Congressional Select Committee on Hunger

This would allow one central committee—and the Roadmap proposes it be bicameral—to focus on issues of hunger, nutrition, and food security.

Required Components of a Comprehensive Strategy to Alleviate World Hunger

The components of a comprehensive federal strategy to alleviate world hunger and promote food security require, first, a well-managed emergency response capability. Second, a comprehensive strategy must include safety nets, social protection, and the reduction of the risk of disaster. Two types of nutrition programs are required: one that focuses on mothers and children, emphasizing comprehensive nutrition before the age of 2; the other incorporates nutrition across the board in all food security programs. Finally, market-based agriculture and the infrastructure necessary for its development must be in place. In all of these areas, the Roadmap proposes a special emphasis on and sensitivity to the centrality of women in securing sustainable food security, increased agricultural development and productivity, and the reduction of malnutrition, undernutrition, and hunger.

Specific Recommendations and Funding Targets

The Roadmap provides specific recommendations and funding targets across a number of accounts in order to measure whether the administration and its agencies are on track to meet these critical global requirements.

The Roadmap Becomes Legislation

House Resolution 2817, the Roadmap to End Global Hunger and Promote Food Security Act of 2009, was introduced on June 11, 2009. The legislation references the total increased investment of $50.36 billion called for over 5 years, fiscal year (FY) 2010 through FY 2014, for agricultural development, nutrition (including maternal and child programs and for other vulnerable populations), school feeding programs, productive safety net programs, emergency response, research and development, and technical assistance programs. In addition, under this bill, the first increase in agricultural development funding for FY 2010 was targeted at $750 million—and President Obama exceeded that and asked for $1 billion.

The Way Forward

President Obama has designated Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to coordinate a government-wide approach to create, design, and implement a comprehensive U.S. strategy on global hunger, nutrition, agriculture development, and food security. This has been implemented and has been reflected in the President’s FY 2010 budget, and the President’s announcements at both the G20 meeting in London and the G8 Summit in Italy. The Roadmap recommendations and the NGOs that make up the Roadmap Coalition have played a critical role in supporting the U.S. coordinated effort.

A number of organizations and voices all pushing in the same direction for similar priorities, such as the Partnership to End Hunger and Poverty in Africa, are important contributors to the Roadmap. The majority of resources will be invested in the areas of greatest need, including Africa and South Asia; however, a number of regions where nations are on the verge of breakthroughs should be included as well. For example, Guatemala and Brazil are carrying out Zero Hunger campaigns, including a special emphasis on ending child hunger. With their leadership, there is a hemisphere-wide initiative to end hunger in the Americas. The United States should be included in this effort and should find ways to support it and contribute to its success.

Emphasis on Nutrition

In June 2009 at the World Food Prize meeting, Secretary Clinton highlighted the seven principles for a food security strategy. The strategy was worrisome because it did not include nutrition. This was different from the comprehensive message presented by Secretary Clinton in a briefing received in April 2009. In addition, nutrition once again failed to have a central role in the announcement at the G8 on agricultural development and global food security.

The emphasis must be made to focus on the under-two population, and the staffing, resources, funds, and coordination must be mobilized for this priority. At the same time, nutrition should be more fully incorporated and emphasized in all antihunger and food security programs. All children need nutritious food, so programs for vulnerable children should fully integrate nutrition into their policies, programs, and projects. Nutritious meals need to be provided to school-age children, and nutrition education must be provided to the children, teachers, parents, and communities served by those schools. Nutrition education should be promoted for pregnant women, in addition to all families and communities that are beneficiaries or touched by such programs. Emergency operations should emphasize nutrition, especially for children of all ages, and use foods that meet the special nutritional and developmental needs of children.

As part of a comprehensive vision, nutrition and food security programs need to integrate the necessary global health interventions into their projects, including

deworming, immunizations, vitamin A supplements, and micronutrient fortification, as well as clean water, hygiene, waste management, and even watershed management. That is a comprehensive approach. That is a government-wide approach. That is the Roadmap.

USAID’S RESPONSE TO THE FOOD CRISIS AND PREVENTING MALNUTRITION FOR THE FUTURE

Michael Zeilinger, M.D., M.P.H.,

Chief of Nutrition Division, Bureau for Global Health

U.S. Agency for International Development

USAID defines food security as existing when all people at all times have both physical and economic access to sufficient food to meet their dietary needs for a productive and healthy life. There are three main components to food security by USAID’s definition—availability, access, and use—and they are each interrelated with the others. Any of these three by itself does not achieve food security. The determinants of food security vary from country to country, region to region, and community to community, but USAID and the U.S. government must strive to achieve food security by addressing the problem comprehensively. Food availability is defined as including sufficient quantities of food from household production, other domestic output, commercial imports, or food assistance. Food access includes adequate resources to obtain appropriate foods for a nutritious diet. This depends on income available to the household, the distribution of income within the household, and the price of food. Food use, or consumption, includes the proper biological use of food, requiring a diet providing sufficient energy and essential nutrients, potable water, and adequate sanitation, as well as knowledge within the household of food storage and processing techniques, basic principles of nutrition, and proper child care and illness management. This presentation will focus on food use or consumption.

Humanitarian Assistance

The global food price crisis began in 2007, and prices peaked in the middle of 2008. In response to the increase and the needs resulting from this crisis, the U.S. Congress provided $1.825 billion to USAID under the President’s food security response initiative. This was in addition to existing funds allocated for humanitarian assistance. With these additional funds, USAID focused mostly on addressing the emergency needs of countries that were most affected by the price increase and provided them with humanitarian assistance. The majority of these supplemental funds were used to provide increased emergency food assistance to such countries as Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Ethiopia. USAID also funded local and regional purchases to complement Title

II resources, and it addressed the immediate impact of rising commodity prices on U.S. emergency food aid programs.

In addition, with the geographic focus in Africa, USAID began to implement longer-term programs that addressed the underlying causes of food security. These programs created diversified household assets, improved economic opportunities for the most vulnerable, preserved livelihood access, increased agricultural productivity, promoted seed quality, supported improved management of acute malnutrition and water and sanitation programs, and reduced the risk of disaster through planning and management and improved irrigation techniques.

Development Assistance

In addition to the humanitarian response, $200 million in development assistance was made available by Congress to focus on increasing agricultural productivity in two key regions, East and West Africa. In West Africa, this money was provided to increase agricultural productivity of staple foods, stimulate the supply response, and expand trade of staple foods. In East Africa, the money strengthened the staple food markets to support local and regional procurement. Finally, funding was also provided to the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) to disseminate off-the-shelf technologies in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

Food Insecurity

In 2008, there was a crisis when food prices increased drastically, but for most of the countries in which USAID works, food insecurity was already a major problem. It remains a major problem with a higher level of poverty and malnutrition than existed just 2 years ago. The United States has primarily responded to global hunger through humanitarian assistance. While this is essential for reducing the suffering of those devastated by humanitarian disasters, the underlying causes of chronic food insecurity need to be addressed, and food insecurity needs to be eradicated through comprehensive programs that address all three pillars of food security—availability, access, and use (consumption).

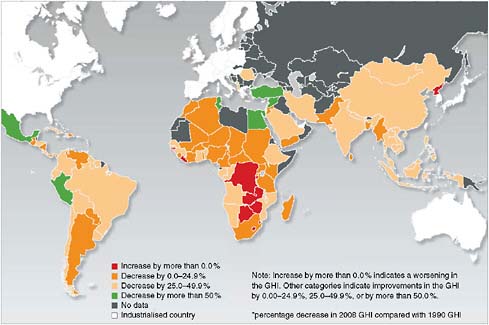

Over the past two decades, there has been insufficient progress in reducing hunger. In fact, as the Global Hunger Index map shows, some countries in central and southern Africa have actually increased their index (Figure 7-1).

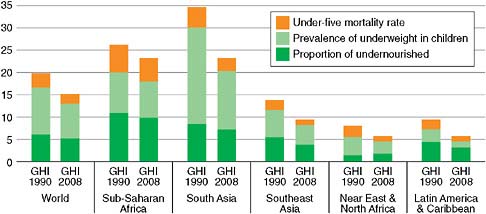

The Global Hunger Index is based on three indicators: under-five mortality rate, the prevalence of underweight in children, and the proportion of undernourished. Figure 7-2 demonstrates the contribution of the prevalence of underweight to the overall index, particularly in Africa and in South Asia, which are home to 114 million underweight children representing 77 percent of the global burden of underweight (Black et al., 2003). Thus, reducing the prevalence of underweight children under 5 years is critical to reducing overall hunger. Focusing on nutri-

FIGURE 7-1 Progress toward reducing the Global Hunger Index (GHI), 1990–2008.

NOTE: Increase by more than 0.0% indicates a worsening in the GHI. Other categories indicate improvements in the GHI by 0.00–24.9%, or by more than 50%. Percentage decrease in 2008 GHI compared with 1990 GHI.

SOURCE: von Grebmer et al., 2008. Reproduced with permission from the International Food Policy Research Institute, http://www.ifpri.org. The original report can be found online at: http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/pubs/cp/ghi08.pdf.

tion as part of a comprehensive food security strategy can help lift families out of poverty, improve economic growth, increase educational attainment, and can even reduce maternal and child mortality (Figure 7-2).

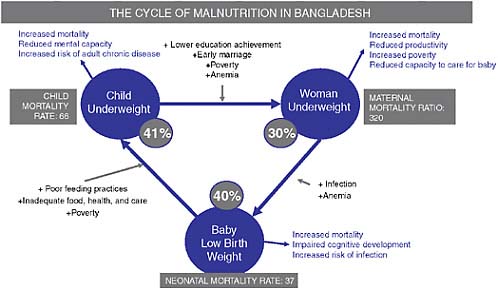

In Bangladesh, about 8 million children are undernourished despite relative availability of food (UNICEF, 2008). There, malnutrition is the cause of two out of three child deaths. It is also the cause of long-term damage to cognitive development, physical growth, and productivity for millions more. The damage caused by malnutrition to physical growth, brain development, pregnancy, and early childhood is irreversible. It leads to permanently reduced cognitive function and diminished physical capacity throughout adulthood.

A family’s nutrition status is perpetuated from generation to generation (Figure 7-3). Malnourished girls are more likely to have children who are malnourished, who will be less productive workers, earn lower wages, and who will develop noncommunicable diseases later in life. In countries like Bangladesh where half the women and children suffer from malnutrition, the losses are staggering. Yet, this entire process is preventable.

FIGURE 7-2 Contribution of three indicators (under-five mortality rate, prevalence of underweight in children, and proportion of undernourished) to the Global Hunger Index (GHI), 1990 and 2008.

SOURCE: von Grebmer et al., 2008. Reproduced with permission from the International Food Policy Research Institute, http://www.ifpri.org. The original report can be found online at: http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/pubs/cp/ghi08.pdf.

FIGURE 7-3 The cycle of malnutrition in Bangladesh.

SOURCE: USAID, 2009.

USAID’s Approach to Food Security

USAID is currently engaged in the process of strengthening its approach to food security and is transitioning to a balanced approach that offers both humanitarian actions for emergency purposes as well as developmental assistance that will increase agricultural productivity, increase trade, support women, and increase support for families, among other components. The support for women and families includes a strong focus on reducing and preventing malnutrition.

The principles that are guiding USAID’s work in nutrition in the Global Health Bureau, include:

-

A focus on the chronically hungry,

-

The window of opportunity is from pregnancy to 24 months,

-

The quality of foods and their use within the household are crucial elements of food security,

-

Prevention of malnutrition is ultimately the most sustainable approach, and

-

Programs should be country owned and designed based on the country-specific determinants of malnutrition and food insecurity.

Malnutrition can be prevented. Evidence-based interventions exist to improve nutrition through integrated community-based approaches, effective targeting, and public-private partnerships. These interventions include the following:

-

Community-based education and counseling programs promote maternal nutrition, exclusive breast-feeding under 6 months, and the introduction of appropriate locally available complementary foods for children aged 6 to 23 months.

-

Micronutrients are provided for the most vulnerable, including vitamin A for children under 5 years, iron for women and children, and iodized salt.

-

Community management of acute malnutrition is integrated into national health services and community outreach.

-

Fortification programs are part of value-chain development with the private sector, including biofortification.

-

Innovative foods for young children are delivered in partnership with the private sector, including ready-to-use complementary foods.

-

Access to and consumption of diverse and high-quality foods is increased by promoting community, school, and kitchen gardens.

FOOD SECURITY IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Nina Fedoroff, Ph.D., Science and Technology Adviser to the Secretary of State and to the Administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development

Global crises abound, and each of them rapidly pushes aside the previous. The current financial crisis has added to last year’s global food and energy crises and even the ever-looming climate change crisis. This presentation will address the U.S. Department of State’s approach to food security and will begin by addressing the changes in the earth’s climate and how these changes have profound implications for food security.

Climate Change and Food Security

The earth has warmed over the past 100 years by almost 1ºC. By now it is no longer contentious to assert that this is anthropogenic.1 The atmosphere’s carbon dioxide concentration has increased by one-third since 1750, predominantly due to the burning of fossil fuel, but also because of deforestation. More importantly, the rate of increase is somewhere between 100 and 1,000 times faster than the rates observed historically.

How will climate change affect the crops that feed the world? The average temperature in Europe in the summer of 2003 was 3.6ºC higher than average, although rainfall was normal. That summer, between 30,000 and 50,000 people died from heat-related causes, a statistic that received much attention. But the effect on crops received little notice: Italy saw a 36 percent decrease in maize yield, while France experienced a 30 percent reduction in maize and fodder yields, a 25 percent decrease in fruit harvests, and a 21 percent reduction in wheat yields. Summer temperatures this high will become more frequent in the coming decades, and by mid-century, such record high temperatures are likely to be the norm. Familiar crops do not survive well at these temperatures, and even a brief period of very high temperatures at the critical time of flowering and pollination can devastate a crop. Temperature also influences how fast a plant develops and reaches maturity. Higher temperatures speed plants through their developmental phases. Annual crops like corn, wheat, and rice set seed just once and then stop producing. As temperature increases from the crop’s optimum, the growing period is shorter. Both the shortening of the growing period and the decrease in photosynthetic efficiency at higher temperatures reduce yields.

Irrigation can be used to cool crops at critical times, however many countries are already unsustainably overpumping aquifers. These include three of the big-

gest grain producers—China, India, and the United States. More than half the world’s people live in countries where water tables are falling.

The primary options to address these issues include more efficient agriculture, particularly with respect to water use; intensive crop breeding; modern molecular genetic modification for both drought and heat tolerance, as well as insect and disease resistance; and development of new crops. Some of this can be done immediately; some will require research and changes in public opinion.

Overall, investments in agricultural development have declined. Historically, rural poverty decreased and agricultural productivity increased with (1) better education, (2) new technologies, and (3) investment. It is essential that the recent trend toward providing food aid at the expense of investing in agricultural research and development be reversed.

Unfortunately, many well-meaning people around the world today believe that genetically modified crops are dangerous. What this means for the present is that modern science cannot be used to improve crops in many countries, including most of Africa. Although the U.S. regulatory apparatus is not completely prohibitive, it is dauntingly complex and so expensive that public-sector researchers have largely turned away from molecular crop improvement. Progress needs to be made in moving toward a regulatory framework that is based on actual risks and real scientific evidence, not hypothetical risks and popular fears.

U.S. Department of State Effort on Food Security

Secretary Clinton sees food security as one of the areas in which the State Department can make a difference. An interagency committee has been working to lay out a vision, goals, and strategy. The vision is straightforward—the United States envisions a world in which all people have reliable access to safe, nutritious, and affordable food. The goals are familiar and very much in line with the Millennium Development Goals. The goals are to:

-

Halve the proportion of young children who are undernourished;

-

Halve the proportion of people who suffer from hunger;

-

Halve the proportion of women and men living on less than $1.25 a day; and

-

Build sustainable agriculture systems that create jobs, increase incomes, and raise agricultural productivity without harming the environment.

The State Department’s strategy has seven pillars:

-

Increase farm and farmer productivity.

-

Stimulate postharvest private-sector growth.

-

Enable private-sector investment and development.

-

Increase trade flows.

-

Support women and families in agriculture.

-

Use natural resources sustainably.

-

Support research and development of agricultural technologies and expand access to knowledge and training.

The substance of the first pillar is expanding access to land, seeds, fertilizer, and irrigation, with an emphasis on women’s access, as well as expanding extension services, training and credit, and working with social entrepreneurs. The second is about transportation networks, storage facilities, and food processing, as well as local procurement, transport, and distribution of emergency food aid. The third is about creating private-sector markets, streamlining business regulations, addressing land tenure, and supporting the development of local organizations to increase participation in decision making. The fourth pillar of the strategy is about developing regional markets, lowering trade barriers, helping to develop food safety standards, improving market information and communications systems, and improving access to finance for agricultural trade and agribusiness development. The fifth is adapting services and training to the needs of women, increasing their access to credit, financial services, education, and land ownership, as well as improving child nutrition through school feeding programs. The sixth is about promoting sustainable agricultural practices and adapting agriculture to climate change. The seventh is about increasing support for the CGIAR; facilitating public-private partnerships, as well as collaborative partnerships between U.S. universities and universities in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and Latin America; and creating a competitive award fund to support research.

The overall strategy relies on the development of country-led plans that bring all stakeholders to the table, as well as the coordination of multilateral support through the UN High-Level Task Force on Food Security. At present, the State Department policy group is engaging with other agencies to develop a “whole-of-government” approach.

USDA’S RESPONSE TO THE CRISES AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Rajiv Shah, Under Secretary and Chief Scientist

U.S. Department of Agriculture

This presentation discusses lessons learned from the U.S. experience and what that means as the country goes forward to try to integrate agriculture with nutrition. Although this is not the first time the global community has come together to try to significantly reduce hunger and poverty in an agriculture-focused manner, it is perhaps the best chance to succeed.

Background

An estimated 1.1 billion people live on $1 a day, and a large portion of that population is dependent on agriculture for its basic economic opportunities and its basic access to foods (The World Bank, 2009). Agriculture is a central component of global extreme poverty. It is not the entire solution to all poverty, but it is simply the largest slice of the most extreme poverty.

A number of people in the world suffer from hunger, which is defined as not having enough basic calories to meet energy needs in a very basic and subsistent manner. A few years ago, this was estimated at 840 million (FAO, 2006), and in 2008 it increased to 960 million (FAO, 2008). It is now reported that there are more than 1 billion hungry people in the world (FAO, 2009). This is a number that is very difficult to comprehend. In addition, 10 million children die each year because they have poor nutrition that makes them prone to diarrheal and infectious diseases that they do not have the physical capacity to survive (Black et al., 2003). These are complex and interrelated problems.

The U.S. Experience

The U.S. experience offers a template for how to potentially address the problem of hunger elsewhere. A long time ago, the United States was a largely agrarian society that struggled to provide enough food to meet the needs of its population. The country was hyperdependent on and responsive to the rain-fed agriculture that was variable, challenging, and difficult. The land-grant university system was developed by Abraham Lincoln in the 1860s, and it started to systematically invest in agricultural research. Coupled with that system, an extension service was created, which today is the most dramatic way to deliver information to farmers that has ever been created. It is the largest adult education program in the country. Basic extension services are the primary means for developing public-sector electronic content that reaches farm communities and rural communities through the e-extension service. Today, 4-H programs are able to reach more children than any other structured program in the federal government—about 6 million children participate in 4-H programs each year.

The coupling of research and extension helped increase U.S. productivity. In addition to these, a third critical component is the developing of structured markets. In the United States, markets have existed and improved over time because of the phytosanitary2 standards that allow commodities to be traded and that allow people to understand what buyers are buying and what sellers are selling. Systems have been in place to ensure the protection of the food supply and our food safety. Such basic market mechanisms often do not exist in the countries that face the biggest burden of hunger.

Nutrition Assistance

The largest percentage of the USDA budget is committed to nutrition assistance programs. Such programs target children, vulnerable populations, and communities that would not otherwise have access to basic food items and would have to spend a very high percentage of their disposable income acquiring food. The United States has a low-cost food supply in which only 11 percent of the average American’s disposable income is spent on food. In the countries with the most vulnerable populations, approximately 70–80 percent of total disposable income is spent on acquiring food. In that environment, when food prices increase, it presents difficult challenges to some very vulnerable populations. The nutrition assistance component of having a robust, active, and self-sustaining agriculture system is an important component that is often overlooked.

Experience of China and India

Lessons can be learned from other countries, including China and India. Over the past few decades, both countries have pursued effective agricultural development strategies and have significantly increased their agricultural productivity through the Green Revolution and crop varieties, along with a range of other policy interventions. China has been far more successful at translating those agricultural productivity gains into reductions in the rates of malnutrition; India has been far less successful. In India, there was less investment in lagging regions—those parts of the country that did not experience the increases in productivity and income—and were essentially left behind as a result. In addition, India lacked infrastructure in nutrition support for rural communities. Even today, a disjointed system exists where there are significant and persistent rates of rural malnutrition and rural poverty, despite having a significant growth rate that created a modern middle class in India. These experiences can provide lessons as new food security strategies are implemented in a range of countries. It will be important to couple nutrition-oriented efforts with agriculture programs in order to maximize their impact.

New Technologies

Research and science can offer unique contributions to the intersection of agriculture and nutrition. Several technologies exist that can improve basic human nutrition in a targeted way for children and women. The first is biofortification. This approach takes the staple foods that some of the poorest populations depend on and enhances them with the micronutrients that women and children need, like vitamin A, zinc, and folic acid.

One example is the orange-fleshed sweet potato. A joint project between the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and HarvestPlus bred higher

amounts of beta carotene into sweet potato varieties in parts of Africa. This project caused a lot of debate and concerns about whether it would actually make a difference in children’s health. Data now demonstrate that introducing a sweeter, orange-fleshed product into the daily food supply has doubled the serum retinol3 in vitamin A–deficient children in northern Mozambique and northern Uganda. The initiative was successful because the product tastes good and children like it. A great deal of investment in agricultural technology development or agricultural foods and productivity has not taken into account the preferences of the people. For biofortification initiatives to be successful, it is important to allow farmers to taste different varieties that are created, and then target efforts on those traits the people want most. This type of research is important and must target the customers. For example, if the customers are malnourished children under 5 years, see what they like, and use that feedback to inform the research.

Another example of a scientific contribution is vegetable breeding. A number of programs are focused on breeding improved varieties of vegetables, while also making sure they are pest and disease resistant. Such research systems exist in the United States and are a reason that the United States is the world leader in agriculture. People in lower-income countries suffering from food insecurity need the same types of research systems to protect their own ability to produce food, particularly vegetables, because they help achieve dietary diversity and improve micronutrient sufficiency in families.

The third area of technological promise concerns livestock. As families’ incomes grow from $2 a day to $10 a day, some of the first luxury items that are brought into the market basket of goods they consume are meat products and dairy products—and thus higher levels of protein. Yet there has been very little effective investment in dairy productivity, livestock improvement, genetic improvement for animals, or pasteurization technologies that would allow smallholder farmers (who don’t have access to large chilling plants or other types of energy systems) to protect their product from spoiling in order to sell it into a more formal market. These technologies are being developed and need to reach small farmers through food security initiatives.

Conclusion

Without extension services, education programs, and the targeting of women, technology alone will not solve the problem of hunger and undernutrition. Technology, however, does hold tremendous untapped potential. The USDA is working to expand its resources in technology development, phytosanitary standards, and market standards, as well as its ability to regulate and develop commercial systems for commodity exchanges. All of those solutions can help to achieve both the agriculture objectives and the health and nutrition objectives that are so

critical in helping millions of low-income children and families lead healthy and productive lives in some of the toughest places on earth.

RENEWING AMERICAN LEADERSHIP IN THE FIGHT AGAINST GLOBAL HUNGER AND POVERTY

Catherine Bertini, Professor of Public Administration

Syracuse University

Dan Glickman, Chairman and CEO

Motion Picture Association of America, Inc.

This presentation describes the objectives and recommendations of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs’ Chicago Initiative on Global Agricultural Development as laid out in its report, Renewing American Leadership in the Fight Against Global Hunger and Poverty, 2009.

Background

In June 2008, work began on the Chicago Initiative with a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The objective of the Chicago Initiative was to generate political, media, and public support for U.S. international leadership to put agricultural development back at the center of U.S. development policy. Food aid remains a top priority, and while the United States should play a critically important role with food aid, U.S. programs should build on food aid and supplement it with additional funding. The United States should have a food security program and a program to support agriculture that can reach the problems where they begin.

The Chicago Council on Global Affairs held a number of meetings with opinion leaders, campaigns, and members of Congress. By the end of 2008, the group had developed a white paper to present to the new administration and met with various transition teams to give them the outline of what was proposed in the plan.

In his inaugural speech, President Obama pledged to work alongside the people of poor nations to help make their farms flourish. In February 2009, the Chicago Council’s report was made public, Catherine Bertini and Daniel Glickman testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and President Obama pledged $1 billion to agricultural development. There were a number of similarities between the Chicago Initiative, the Global Food Security Act, and President Obama’s plan—especially the emphasis on agriculture education and research, infrastructure, policy coordination, and strengthening USAID in public-private partnerships (Table 7-1).

TABLE 7-1 Comparison of Three Versions of U.S. Food Aid

|

|

Chicago Council on Global Affairs |

Global Food Security Act |

President Obama’s Plan |

|

Goal |

Mobilize U.S. knowledge, training, assistance, and investment to increase the productivity and income of smallholder farmers. |

Alleviate poverty and enhance human and institutional capacity by investing in agricultural research and education. |

Improve the lives of poor populations by focusing on agricultural growth in rural communities. |

|

Agricultural education and research |

Increase USAID-sponsored scholarships, U.S. land-grant universities’ partnerships, and agricultural research at CGIAR. |

Collaborate with U.S. land-grant universities to increase support for agricultural research including genetically modified technology. |

Work with U.S. landgrant universities to expand development and use of modern technology and strengthen host country research institutions. |

|

Rural and agricultural infrastructures and market access |

Increase support for rural and agricultural infrastructure, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, working with international financial institutions. |

Improve agricultural infrastructure, finance and markets, safety net programs, job creation, and household incomes. |

Strengthen national and regional trade and transport corridors to boost farmers’ access to seeds, fertilizers, rural credit, and markets. |

|

Policy coordination |

Create Council on Global Agriculture and a deputy in National Security Council. |

Create a Special Coordinator for Global Food Security within the Executive Office. |

N/A |

|

USAID’s role |

Strengthen the leadership and in-house capacity of USAID. |

Designate USAID as the lead agency. |

USAID to develop a comprehensive Food Security Initiative. |

|

Encourage public-private-partnerships |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Cost |

$341.05 million (first year) $1.03 billion (fifth year) |

$750 million (FY 2010) $2.5 billion (FY 2014) |

$1 billion (FY 2010) |

Chicago Initiative on Global Agricultural Development Report Recommendations

A strategic plan for combating global hunger and poverty must involve agricultural development, emergency food assistance, nutrition, agricultural research, extension, and investment in modern methods of agriculture. The Chicago Initiative provided the following recommendations in its report:

-

Increase support for agricultural education.

-

Increase support for agricultural research.

-

Increase support for rural infrastructure.

-

Improve the national and international institutions that deliver agricultural assistance.

-

Revise U.S. agricultural policies.

Agricultural Education

The Chicago Initiative recommends increased USAID support for sub-Saharan African and South Asian students studying agriculture; increased American agricultural university partnerships with universities in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia; direct support for agricultural education, research, and extension for young women and men; a special Peace Corps cadre of agriculture training and extension volunteers; and support for primary education for rural girls and boys through school feeding programs.

Agricultural Research

This recommendation aims to increase support for agricultural research in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. This includes providing external support for agricultural scientists working in national agricultural research systems, research conducted at the international centers of CGIAR, collaborative research between scientists from sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia at U.S. universities, and creating a competitive award fund to provide an incentive for high-impact agricultural innovations to help poor farmers.

Rural Infrastructure

The Chicago Initiative recommends increased support for rural and agricultural infrastructure, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. This recommendation also encourages a revival of The World Bank lending for agricultural infrastructure in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. In addition, it recommends accelerating disbursal of the Millennium Challenge Corporation funds already obligated for rural infrastructure projects.

Institutional Reform

This recommendation is to improve the national and international institutions that deliver agricultural development assistance. It recommends restoring the leadership role of USAID; rebuilding USAID’s in-house capacity to deliver and administer agricultural development assistance programs; improving interagency coordination for America’s agricultural development assistance efforts; strengthening the capacity of the U.S. Congress to collaborate in managing agricultural development assistance policy; and improving the performance of international agricultural development and food institutions, notably FAO.

Policy Reform

This Chicago Initiative recommendation aims to improve U.S. policies currently seen as harmful to agricultural development abroad. There is a need to improve America’s food aid policies, repeal current restrictions on agricultural development that might lead to more agricultural production for export, review USAID’s long-standing objection to any use of targeted subsidies to reduce the cost to poor farmers, revive international negotiations aimed at reducing trade-distorting policies (including agricultural subsidies), and adopt biofuel policies that place a greater emphasis on market forces and on the use of nonfood feed stocks.

Next Steps

The Chicago Initiative highlights a number of issues and makes recommendations on them; however, it is important to note that the main challenge is prioritizing these issues and providing leadership within the U.S. government to nonprofits, universities, and international NGOs. The next steps include:

-

Expansion of G20 initiatives,

-

Passage of the Global Food Security Act,

-

Strengthening leadership of USAID,

-

Continued agricultural development advocacy activities,

-

A strategy for leveraging donors and international organizations,

-

Continued in-depth discussion of key agricultural development issues, and

-

Creativity of Obama appointees.

This is a collective responsibility; now that the U.S. government has made these issues a priority, and the G8 has placed them on the agenda, it will take additional pressure to develop the strategic plans and the leadership to make sure the goals are reached.

DISCUSSION

This discussion section encompasses the question-and-answer sessions that followed the presentations summarized in this chapter. Workshop participants’ questions and comments have been consolidated under general headings.

Coordinating U.S. Global Health Initiatives

A number of U.S. initiatives that currently exist could naturally be blended, such as food and nutrition programs with HIV/AIDS programs. It was noted that the administration is working to integrate the various agencies and programs into one comprehensive plan. A wide variety of issues are part of a worldwide global health initiative; however, food and agricultural issues do not attract the same interest as a number of other issues. For example, AIDS and malaria initiatives get much support worldwide, especially when compared to the international hunger effort, whose political resonance is not nearly as developed or as widespread. It is positive to note that governments, NGOs, and foundations are beginning to take hold of this issue and develop the political will to make these issues an important part of global development efforts.

Political Will

Sustaining political will is an important element to defeating global hunger and undernutrition. How can this be sustained in an environment in which so many important issues are on the table? Policy makers are faced with a multitude of simultaneous issues, so the key is to find leaders who are willing to sustain the effort and articulate the problems in a way people can understand. For example, in the area of food assistance, the public does recognize the moral and humanitarian aspect, which has helped gain support for food aid. However, agricultural assistance has fallen off the map and needs to be restored. People have become disengaged with trying to “help people help themselves” in the world of agriculture. It was noted that because food security is now on the President’s agenda, support is growing because people realize that food and economic issues affect everyone—not just the NGO and university communities, but the American private sector and corporate world as well.

The Role of Food Aid

The view was expressed that the United States should not lead its fight against global hunger with food aid (although food aid should not be decreased and more flexibility should be allowed for local purchase of food). Food aid becomes more important in emergency situations when there is no other food available for purchase, or where buying food in the market would greatly disrupt

the market and increase prices in others areas. In the United States, there are some important constituencies involved in food aid, including commodity groups and shippers, that make reform of food aid challenging.

U.S. Leadership

The role of the United States as a leader in coordinating the number of organizations that work in the nutrition landscape was discussed. It was noted that a coordination role is more important than a commanding role. It is important for the United States to listen to what works in other countries and help guide sustainable food security solutions according to the local context.

It was noted that in the field, although there are competing interests, there is actually much more synergy among various agencies and groups than is seen in Washington, DC. Typically, the countries with the worst hunger and development indicators actually have more synergy within the U.S. overseas missions. In these situations, those on the ground see what needs to be done and are able to put aside their differences to improve the dire situation in that country.

WORKSHOP CLOSING REMARKS

Reynaldo Martorell, Ph.D., Robert W. Woodruff Professor of Public Health

Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University

In reflecting on the workshop, Dr. Martorell drew attention to the fact that the title of the workshop, Mitigating the Nutritional Impacts of the Global Food Price Crisis, spoke about that price crisis alone. As the planning committee began preparations for the workshop, however, the financial crisis occurred and the planning committee decided to expand the workshop’s focus to include both the food price and the economic crisis in the workshop proceedings.

During the 3-day workshop, many topics were covered by various presenters. Per Pinstrup-Andersen gave a detailed analysis of the global food price crisis; he highlighted the fact that it was not only the high prices for commodities, but also the price volatility that caused a great deal of problems. Dr. Pinstrup-Anderson further pointed out that prior to the food crisis, commodity prices were too low to provide a good livelihood for producers and to encourage investment in agriculture. In this way, low prices are also a problem.

Hans Timmer from the World Bank spoke about the financial crisis. Not only were the countries that participate actively in financial markets impacted by this crisis, but also the countries of sub-Saharan Africa, for example, were also very much impacted. While the price of commodities did decrease during the financial crisis, prices on average remained higher than before the food price crisis. It is important to note that governments’ capacities to respond with safety nets are weakened because of the financial crisis. It is therefore crucial for the

global economy—and in the best interests of the United States—that developing countries begin to have healthy economies; this is part of the solution for the global economy.

Marie Ruel discussed the fact that vulnerable people in urban areas were expected to be affected most severely because they are net buyers of food. In reality, though, a substantial number of people in rural areas also seem to be gravely affected. The country experiences described by the case studies demonstrated the fact that the data are not ideal, and a variety of nutrition surveillance mechanisms were discussed. The session that examined the global response made clear that the crisis did not affect every country in the same way and there was tremendous diversity in response. In many cases, governments’ reactions exacerbated the problem by imposing export bans and interfering with trade. Among the negative nutritional effects that were described in the presentations were deteriorations in dietary quality when people eat less of more expensive foods; typically more expensive foods are the more nutrient dense foods such as meat, vegetables, and fruits.

The food price and financial crises present an opportunity to rethink approaches to food security and nutrition, to coordinate and deploy systems in a better way, to motivate policy makers at national and global levels to a greater commitment to action, and to do effective advocacy. There was much discussion about forging partnerships with the private sector, NGOs, and civil society, and to advocate for an increased level of resources. Workshop participants talked about a way forward, which includes increasing investment in agriculture, increasing productivity, and bringing science and technology to bear.

The Way Forward—Themes from the Workshop

The following themes emerged during the workshop through several speakers’ presentations and during discussion sessions with workshop participants. These themes are not intended to be and should not be perceived as a consensus of the participants, nor the views of the planning committee, the IOM, or its sponsors.

-

The current crisis presents an opportunity to motivate donors and engage affected country governments in efforts to address undernutrition, hunger, and food insecurity in vulnerable populations.

-

There is a window of opportunity with women and children where known nutritional interventions will be most effective and have a long-term payoff, as described in the 2008 Lancet series on maternal and child undernutrition.

-

There is a simultaneous call for better quality data to inform program design and effectiveness, but there is also a critical need to immediately move forward with proven programs and policies to mitigate hunger and undernutrition in vulnerable populations.

-

Short-term, emergency actions are not sufficient to remedy recurring food crises; instead, both short- and long-term investments in global food and agriculture systems are needed.

-

Mechanisms to help vulnerable populations cope with food price volatility and to prevent future shocks are required.

-

It is important to draw upon the expertise of governments, NGOs and civil society, the private sector, foundations, and the broad spectrum of actors in the international nutrition and agriculture sectors.

-

The roles of the multiple UN agencies that work to promote the food and nutrition security of vulnerable populations need to be clarified.

-

Fostering engagement with the private sector may yield new expertise and resources.

-

A stronger voice from indigenous NGOs is needed. Such local NGOs could benefit from capacity-building efforts to encourage ownership and political involvement.

REFERENCES

Black, R., S. Morris, and J. Bryce. 2003. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? Lancet 361(9376):2226-2234.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2006. The State of Food Insecurity in the World. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

———. 2008. Number of Hungry People Rises to 963 Million. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

———. 2009. 1.02 Billion People Hungry. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

Renewing American Leadership in the Fight Against Global Hunger and Poverty: The Chicago Initiative on Global Agricultural Development. 2009. Chicago: The Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

The World Bank. 2009. Food Crisis: What The World Bank is Doing. Retrieved November 9, 2009, from http://www.worldbank.org/foodcrisis/bankinitiatives.htm.

UNICEF. 2008. The State of the World’s Children 2009: Maternal and Newborn Health. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund.

USAID. 2009 (unpublished). The Cycle of Malnutrition in Bangladesh.

von Grebmer, K., H. Fritschel, B. Nestorova, T. Olofinbiyi, R. Pandya-Lorch, and Y. Yohannes. 2008. The Challenge of Hunger: The 2008 Global Hunger Index. Bonn: Welthungerhilfe; Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute; Dublin: Concern Worldwide.