3

Impacts on Nutrition

The global poor are usually the hardest hit by food price increases and economic strife. At the household level in developing countries, poor consumers spend 50–70 percent of their budget on food (von Braun et al., 2008), so their capacity to respond to higher food prices (or reduced incomes) is limited, and often forces households to make difficult choices that adversely affect women and children. This chapter highlights the theoretical pathways and evidence base around how the dual crises are affecting nutrition. As described by moderator Isatou Jallow of the World Food Programme, the following presentations helped workshop participants to understand the pathways from the food and economic crises to nutritional impact, including a discussion of existing evidence and vulnerable populations.

CONCEPTUAL PRESENTATION ON PATHWAYS TO NUTRITIONAL IMPACT

Ricardo Uauy, Ph.D., Professor, Public Health Nutrition and Pediatrics

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; Institute of Nutrition INTA, University of Chile

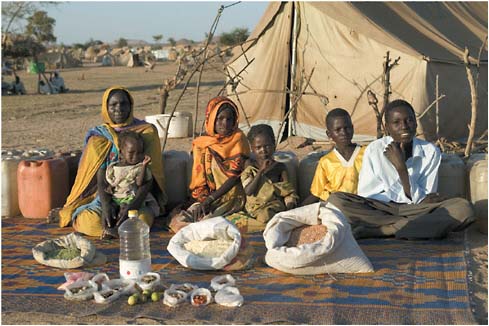

The pictures below illustrate the substantial difference in food expenditures of families in different areas of the world. This demonstrates how income directly affects the ability to maintain good nutrition through food consumption (Figures 3-1 to 3-6).1

A Survey of Food Expenditures Around the Globe

In Germany, families spend about $500 per week to feed a family of four. There is much variety, including a great deal of processed foods, although fresh fruits and vegetables are also prominent in the household (Figure 3-1).

In Cuernavaca, Mexico, families spend about $189 per week. Here fruits and vegetables are abundant, although processed foods and sweetened beverages figure prominently (Figure 3-2). In this situation, if it is necessary to make do with a reduced income, it is possible to decrease food quantity without necessarily sacrificing the food quality. Ironically, a reduced income might cause the family to cut out the unnecessary processed foods and soft drinks, which would improve this family’s nutritional status.

In Cairo, a family spends $69 dollars per week on food. This amount of weekly expenditure in Egypt still enables a fairly varied diet (Figure 3-3).

In Quito, Ecuador, however, families spend about $32 on food, and sacks of cereals, wheat, and some legumes are featured prominently (Figure 3-4). Less fruits and vegetables are seen as compared to the previous families’ diets. In this scenario where there is less variety, if some foods are eliminated from the picture, the family’s consumption will suffer in nutritional quality.

FIGURE 3-1 One week of food for the Melander family in Germany.

SOURCE: Menzel and D’Aluisio, 2005.

FIGURE 3-4 One week of food for the Ayme family in Ecuador.

SOURCE: Menzel and D’Aluisio, 2005.

A family in Bhutan can only afford $5 per week for its food. There is less food overall, and it is basically plant foods, including fresh fruits and vegetables. There are less animal foods, as grains figure prominently (Figure 3-5).

A family in Chad spends only $1 on food each week. The essence of their meager diet is cereals and some legumes, and almost exclusively features plant foods (Figure 3-6).

Diet Quality Suffers in Times of Crisis

These pictures demonstrate what foods people buy with the amount of money they have to spend on food each week. While these photos convey the present status of these populations, they suggest what people might stop buying if they had less money—during a food crisis, for example. In crisis situations, families preserve diets based on less expensive foods. If their income is sharply reduced, families do away with animal foods and nonstaple foods. They eat less meat, less dairy, less processed foods, less vegetables, and less fruits; they are predominately dependent on cereals, fats, and oils. They find ways to get adequate energy at a very low price, but may forego appropriately nutritious foods, which results in poor quality diets that are inadequate in terms of micronutrients (unless these sources are fortified, such as the fortified cereal and oil provided by the UN World

Food Programme [WFP]). Continued access to energy-dense, micronutrient-poor diets in urban setting leads to increased risk of obesity, setting the stage for diet-related chronic diseases of adults (Victora et al., 2008). Micronutrients need to be preserved in diets, even during times of crisis.

Poor-Quality Diets Increase Morbidity and Mortality

Income has a major effect on the access that various populations have to a nutritious variety of foods, specifically animal foods, fruits, and vegetables. Income not only affects what people buy and what they eat, but it also directly affects the health of children, as well as their cognitive and immune functions. Poor nutrition leads to increased infection, which, in turn, compromises nutrition. Breast milk is a protective factor during the crucial first year of life and beyond, both in terms of its capacity to provide food energy and protein, but also as an immune enhancer and a protective factor against infections (Black et al., 2008). In fact, breast-feeding promotion is the most cost-effective means of saving 1 million out of the 3.5 million children younger than 5 years that are presently dying from all causes related to nutrition. Exclusive breast-feeding is recommended for the first 6 months of life. However, suboptimum breast-feeding, especially non-exclusive breast-feeding in the first 6 months of life, is estimated to be responsible for 1.4 million deaths and 10 percent of the disease burden in children younger than 5 years (Black et al., 2008). Among children living in the 42 countries with 90 percent of child deaths, a group of effective nutrition interventions including breast-feeding, complementary feeding, and vitamin A and zinc supplementation could save about 2.4 million children each year—25 percent of total deaths (Jones et al., 2003).

Poor Nutrition Also Has Lasting Economic Impacts

Deficiencies in diet quality during the ongoing food crisis have the greatest impact on women of reproductive age and children under 3 years, especially children under 18 months. At the same time, families with fewer resources will use less money for education, housing, and medical care, likely compounding the effects of the food price crisis for the most vulnerable groups.

A recent examination by the Economic Commission for Latin America showed that only 10 percent of the cost of hunger in Latin America was related to health or poor educational performance. Instead, almost 80 percent of the negative consequences of hunger were linked to reduced productivity throughout the life course. In this way, economic growth will be restricted by the productivity of those children who are suffering the negative impacts of the global food crisis, and that will have a long-term, transformational effect upon society’s develop-

ment. In addition to the short-term nutritional effects of the food crisis, then, there may also be long-term effects that need to be considered.

Conclusion

The following conclusions were drawn about the food crisis and its impact on nutrition:

-

Demand for food staples that provide energy (rice, wheat, maize, sugar) is less affected by prices and income than nonstaple foods (meat, dairy, pulses, fruits, and vegetables).

-

Critical essential micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) are concentrated in nonstaple foods. The consumption of these more expensive, less affordable foods is very price sensitive.

-

Present global malnutrition is characterized by poor intake of vitamins and minerals, resulting in high prevalence rates of micronutrient deficiencies.

-

Modest decreases in current intakes of vitamins and minerals will increase prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies, affecting the short- and long-term nutrition and public health of the poor.

-

The challenge is not only to prevent a reduction in the quantity of food, but also to preserve the quality of the food consumed. The solution to hunger and malnutrition is not achieved by providing only food energy in sufficient amounts; the food should also be of adequate micronutrient content and quality.

-

Unfortunately, micronutrient-rich foods are normally the more expensive foods. The international nutrition community must make a stronger effort at fortification and biofortification in order to make micronutrients available for vulnerable groups, especially children and women of reproductive age, and especially during times of crisis.

-

The food price crisis is already having a significant impact on the world’s ability to reach the first UN Millennium Development Goal (MDG). The number of food-insecure people has increased; thus, the goal of halving the number of hungry people by 2015 will certainly not be met. Moreover, malnutrition in its various forms will restrict the international community’s capacity to meet all other MDGs.

EXISTING EVIDENCE OF NUTRITIONAL IMPACTS

Francesco Branca, M.D., Ph.D., Director,

Department of Nutrition for Health and Development

World Health Organization

The Global Impact

For the first time in human history, more than 1 billion people are undernourished worldwide. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimate that 1.02 billion people worldwide—one-sixth of humanity—are undernourished (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2009). This is about 100 million more than last year. Unless substantial and sustained remedial actions are taken, the Millennium Development Goal and World Food Summit target of reducing the number of undernourished people by half by 2015 will not be reached. The latest estimates of the FAO show a significant deterioration of the already disappointing trend witnessed over the past 10 years. The spike in numbers of undernourished in 2009 underlines the urgency to tackle its root causes swiftly and effectively.

The current global economic slowdown, which follows and partly overlaps the food and fuel crisis, is at the core of the sharp increase in numbers of undernourished in the world. It has reduced incomes and employment opportunities of the poor and significantly lowered their access to food. The increase in undernutrition is not a result of limited international food supplies. Recent figures of the FAO Food Outlook indicate strong world cereal production in 2009.

With lower incomes, the poor are less able to purchase food, especially where prices in domestic markets are still high. While world food prices have retreated from their mid-2008 highs, they are still high by historical standards. Also, prices have been slower to fall locally in many developing countries.

At the end of 2008, domestic staple foods still cost on average 24 percent more in real terms than 2 years earlier, a finding that was true across a range of important foodstuffs (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2009). The combination of lower incomes caused by the economic crisis and persisting high food prices has been devastating for the world’s most vulnerable populations.

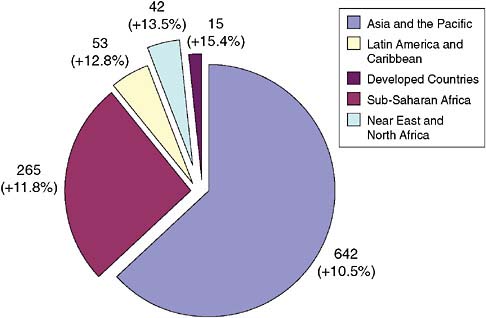

The declining trend in the rate of undernutrition in developing countries since 1990 was reversed in 2008, largely because of escalating food prices (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2009). As seen in Figure 3-7, 642 million of the world’s undernourished are in Asia and the Pacific, with a majority in developing countries; almost 300 million are in sub-Saharan Africa. Both these regions have seen a 10 percent increase in numbers of undernourished from 2008 to 2009 (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2009).

Because these data are from 2007, they do not answer the question as to

FIGURE 3-7 Estimated regional distribution of undernourished in 2009 (in millions) and increase from 2008 levels (in percentage).

SOURCE: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2009.

whether the food price crisis produced these results. It is likely that a combination of events caused the reversal in the declining trend of numbers of undernourished, including the HIV epidemic and major human-made disasters. How, then, can the impact of the food price crisis be measured? A number of organizations such as Action Against Hunger and Save the Children have been looking at data in newspapers and existing literature; other organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) have been actually collecting data, but the data are sparse and anecdotal. It is very difficult to have a comprehensive, systematic picture of the impact of the food price crisis on the nutritional status of vulnerable groups.

Lessons have been learned from previous crises. The 1994 devaluation of currency in the Congo led to an increase in wasting among mothers, more babies born with low birth weight, and a greater level of stunting and wasting among children. A few years later in Indonesia, the financial crisis led to increased wasting in mothers and higher prevalence of anemia in mothers and children, although strangely no increase in childhood malnutrition. The Dutch famine of 1944 showed that the negative experiences of mothers during the famine had significant consequences on their children, including not only low birth weights, but also increased risks of noncommunicable diseases like obesity, mental disorders,

behavioral problems, increased blood pressure, and coronary heart disease. This knowledge should cause great concern about what will happen to those who are now experiencing food shortages.

What Nutritional Impacts Are Expected?

Not everyone is affected equally by high food prices. It is expected that households that are net food buyers would lose with rising food prices, while net food-selling households stand to gain. Even within households, however, individual members are likely to be affected by food crises in different ways, with the nutritionally vulnerable members—women of childbearing age and young children—most at risk.

Households that are net consumers in rural and urban areas are most likely to face the negative effects of high food prices, and households’ resilience to these increases will depend on their available coping strategies. Typically, poor households have limited strategies in which to cope with such shocks. Reducing household expenditure in other areas may mean a reduction in spending on education and health service utilization, therefore affecting child well-being. The impact on girls’ education and nutrition in certain areas of the world may be particularly severe, due to strong cultural preferences toward sons (girls are less likely to be kept in school and may be fed differently than boys).

A decrease in purchasing power causes people to purchase fewer nutrient-dense foods, such as animal-source foods (meat, poultry, eggs, fish, and milk), fruits, and vegetables. When the “savings” brought about by this coping strategy is not enough, they may also reduce expenditure on basic foods, such as sugar, oil, and salt, as well as staples. In this way, the intake of specific nutrients, in particular micronutrients, is reduced before energy intake is reduced.

The Impact of the Food Crisis: Evidence from Case Studies

To evaluate exactly what the effect of the food crisis is in various countries, their particular resilience and capacity to cope must be understood. Such capacity is very different in various countries and even within households. The following case studies, from Tajikistan, Ethiopia, Cambodia, and Sierra Leone, paint a picture of how four countries have reacted to the crisis.

Tajikistan

In Tajikistan, 91 percent of households are net food buyers. The shock of food price increases in 2008 caused a severe increase in undernourished in this country. In 2009, the majority of food-insecure households improved to the point where they are only moderately food insecure. For these households, access

to food has improved, mostly thanks to the return of migrants, the transfer of remittances before the winter months, and the stable (but still high) food prices. On the other hand, these households remain vulnerable to shocks as most have not built sustainable assets and continue to use such negative coping strategies as skipping entire days without eating or eating “famine foods” such as seeds. This difficult and precarious economic situation is forcing households to contract new debts mostly to buy animal feed. One-half of the households surveyed have taken on new debts, and one-third of them will take longer than 2 months to pay them back (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank, 2009).

Ethiopia

In Ethiopia, during the 2008 food price hikes, the cost of maize increased by more than 75 percent, cabbage by more than 66 percent, and haricot beans by more than 20 percent (Action Contre la Faim, 2009). High international prices of cereals and inflated oil prices in the region had some effect, but drought and conflict remain the most significant factor behind the price rises of locally produced foods. Consumption of high-quality, micronutrient-rich foods was reduced while staple food consumption remained largely the same. In Ethiopia, it is likely that staple foods will continue to be replaced by cheaper, lower-quality staples: maize will be replaced by kocho, which has a lower vitamin A and protein density than maize (Abebe and Singburaudom, 2006). At the national level no increase in malnutrition rates were seen. However, survey data from 3 districts indicate that rates of malnutrition and under-five mortality increased in late 2007 and early 2008, corresponding with high food prices. No change in malnutrition rates was seen at the national level, indicating that country-level data are too imprecise to inform policy making and that surveillance data from the local level is needed (Action Contre la Faim, 2009).

Cambodia

Cambodia is classified as chronically food insecure as defined by the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification. All of the indicators are very close to crisis levels, and there are signs of negative change. The urban poor may have been more affected by rising food prices than the rest of the country; in urban areas, consumption of nearly all food groups (12 of 14) has decreased, and mean consumption has dropped from 5.4 to 4.8 food groups. Consumption of meat and fish has dropped 14 percent. Perhaps the most alarming finding is that the percentage of wasting among the urban poor has risen from 9.6 percent in 2005 to nearly 16 percent in 2008 (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2008).

Sierra Leone

Since 2002, Sierra Leone has been recovering from civil war. Food prices are intensely political, and undernutrition remains a threat to long-term security. Malnutrition remains very high, with 27 percent of children under 5 years reported as underweight. High inflation (more than 10 percent), stunting rates (37 percent), and poverty levels (between 65–75 percent) prompted FAO to rank Sierra Leone sixth in its assessment of nations most vulnerable to global price rises (Action Contre la Faim, 2009).

From January to March 2008, rice prices increased by 64 percent, and fuel prices increased by about 15 percent between January and May. The price rises corresponded with the beginning of the annual “hunger season,” when families rely more on imported rice because local produce is more expensive and in short supply before the harvest. A survey was conducted in Freetown, home to more than 760,000 people, of whom 60 percent are under 25 years old and 97 percent rely primarily on the market for food. Areas experiencing the greatest increase in prices were also the areas where people most decreased the quantity of rice eaten per day. Meat consumption was most radically affected, and 43 percent of respondents reported they no longer consumed meat (Action Contre la Faim, 2009).

Conclusions

A number of conclusions and recommendations can be offered. The first conclusion is that the available data are poor. The data are often sparse and oftense and often anecdotal, although good monitoring systems on prices of commodities and on expected numbers of undernourished exist. However, nutritional surveillance is not performed systematically.

One recommendation to improve this situation emphasizes better surveillance. To achieve this, protocol standardization and technical and financial resources are needed. The best methodology for improved surveillance needs to be determined; for example, can national surveys and hot spot monitoring be combined? In addition, the nature of the data must be broadened to include food consumption, nutritional status, health outcomes, socioeconomic and policy context, growth velocity, and micronutrient data.

The second conclusion is that nutritional impact varies by population and is possibly linked to the extent of stress and resilience. Variations in dietary intake and coping mechanisms in response to an increase in food prices include reduction of nutrient-dense foods, reduction of meals, reduction of portions, and use of “famine foods.”

The recommendations for dealing with the varying nutritional impacts on the population are to detect hidden nutritional effects and to identify and monitor vulnerable populations. To achieve this will require documenting nutritional impacts in population subgroups; identifying and monitoring micronutrient deficiencies

in vulnerable groups; tracking such long-term effects as low birth weight and chronic diseases; following population groups, such as the elderly; monitoring vulnerable households; and evaluating the coverage and impact of nutrition interventions for targeted populations.

ARE THE URBAN POOR PARTICULARLY VULNERABLE?

Marie Ruel, Ph.D., Director, Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division

International Food Policy Research Institute

Poverty Better Indicator of Food Crisis Impacts Than Geography

In the next quarter century, the population explosion that characterized much of the previous century will be replaced by another dramatic transformation: urban population growth on an unprecedented scale. About half of the world already lives in cities, and by 2025 almost 50 percent of Africans and Asians and 80 percent of Latin Americans will live in urban areas (UN, 2004).

Urban dwellers have limited access to agriculture and to land, so they must purchase most of their food; they are net buyers, which means they purchase more of their calories than they produce. For this reason, they need to have access to income. Urban people have to work in order to get cash to buy food. Because they need employment, very often women work outside the home in addition to men.

Are the urban poor truly particularly vulnerable to the food price crisis and its impacts? The evidence regarding whether or not the urban poor really are suffering the most is largely anecdotal. It often comes from small context-specific and nonstatistically representative studies. The media has declared there needs to be a focus on the urban poor, and the urban poor also have made themselves heard with food riots. The hypothesis is that the food price crisis affects the urban poor disproportionately. Intuitively, it seems this must be true because they purchase most of their food; so as food prices rise, the urban poor must be unduly affected. With the arrival of the current global economic crisis, it is presumed that the phenomenon has intensified the vulnerability of the urban poor because it has reduced employment opportunities. At this point, no documented information regarding the effects of the economic crisis on urban populations has been found.

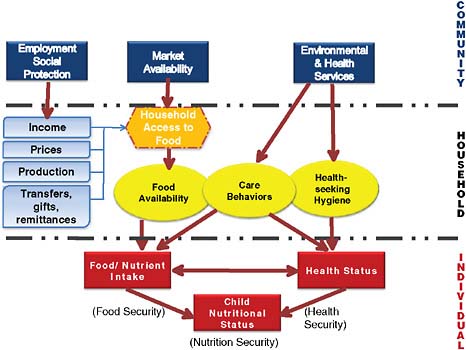

Figure 3-8 is a conceptual framework on the determinants of child nutrition. On the left side are listed the different factors affecting household access to food: income, prices, production, and transfers and remittances. The relative importance of these factors differs in urban and rural areas because in urban areas people have less access to production and therefore they need income, or jobs to generate income; they also need reasonable prices to have adequate access to food. If none of these factors exist, urban dwellers use transfers, remittances,

FIGURE 3-8 Determinants of food, nutrition, and health security in urban areas.

or other social protection mechanisms. The food price crisis is affecting these access factors, and it is affecting overall food availability at the household level. The response of households and their coping strategies—how resources are reallocated in terms of who works, how many hours they work, whether children are taken out of school to work, who eats what—is where households can make some adjustments. They can change such behaviors as their use of health services or the allocation of resources within the household and make decisions about who works, for how many hours, and where.

It is widely accepted that urban populations are net buyers of staple foods; what is often not discussed, however, is that there is also a very large proportion of rural dwellers who are also net buyers of staple foods. Table 3-1 shows nine different countries; overall, 96 percent of the urban populations are net buyers versus 74 percent of the rural dwellers. Among the poor, the rural poor have the highest percentage—88 percent are net buyers. In this light, the rural poor and the urban poor are all net buyers, meaning poverty is probably more important than geography in determining the effects of the food price crisis.

A special 2008 issue of Agricultural Economics also found that the poorest are the ones who suffer the most from the food price crisis, irrespective of

TABLE 3-1 Net Buyers of Staple Foods: 96% of Urban and 74% of Rural Dwellers

country, region, and geographic area. The journal also found that female-headed households suffer disproportionately. The most vulnerable groups were found to be the poorest, the urban, those who do not own land, the nonfarmers, the larger households, the less educated, the less well-served by infrastructure, and those who live in a rural area and have limited access to land and modern agricultural inputs—essentially people who are poor or ultra-poor and need money to purchase food (Headey and Fan, 2008).

Coping Strategies

The impact of the global food crisis on food security will depend a great deal on the food-related coping strategies that affected households adopt. There are strategies that revolve around food, such as switching to cheaper, less preferred, lower-quality foods; buying less food, skipping meals, and reducing food intake; decreasing intake of nonstaple foods; eating out and increasing consumption of street foods; using different ingredients and cooking methods; and modifying the allocation of resources within the household.

There are also nonfood coping strategies such as boosting agricultural production and even returning to rural areas if the household owns land; augmenting income through child labor and women working outside the home; increasing the number of hours worked; taking children out of school; reducing spending on nonfood (health, education); and other desperate measures such as sending children to live with relatives or putting them up for adoption. The most detrimental of these coping strategies are those that include deinvesting in children, as noted

above, as this will have long-term consequences on those children’s development and future earning potential.

Conclusions and Lessons Learned

The following conclusions and lessons learned were offered:

-

The urban poor are clearly vulnerable to the food price crisis and will most likely be extremely vulnerable to the financial crisis as well.

-

Landless rural poor (who were vulnerable to start with) are net buyers and are extremely vulnerable; the dichotomy of the urban poor versus the rural poor may not be necessary except when you think of delivery mechanisms for interventions.

-

The magnitude and severity of suffering depends on the families’ ability to adapt and on the specific nature of coping strategies adopted.

-

Several coping strategies may have long-term irreversible consequences on transmission of poverty (e.g., deinvesting in children).

-

It is critical to identify the most vulnerable households and individuals and apply a rapid and effective response to prevent further deterioration.

-

It is critical to understand the most vulnerable households’ coping strategies in order to craft both short-term and long-term responses.

-

The international community was ill prepared for this crisis in that early-warning, monitoring, and surveillance systems were lacking; not much is known about the impact of the crises on nutrition.

-

Global and national responses should support, rather than undermine, the coping strategies adopted by the poor; the response should prevent such households from adopting coping strategies that will cause long-term irreversible damage on human capital formation.

-

Targeted nutrition interventions need to be better incorporated into agricultural interventions, social protection programs, income generation projects, and women’s empowerment programs; the international nutrition community must work across sectors and integrate nutrition interventions into the global development agenda.

DISCUSSION

This discussion section encompasses the question-and-answer sessions that followed the presentations summarized in this chapter. Workshop participants’ questions and comments have been consolidated under general headings.

Remittances

Remittances have become very important in recent times and are particularly affected in the global financial crisis. In many countries that are very dependent on remittances, the WFP has evidence of current remittances decreasing rapidly and drastically for the first time in 20 years. In urban areas, people are either recipients of international remittances, or they themselves send remittances to rural areas. Although the impacts from the financial crisis are primarily seen on middle-income groups, remittance issues are the notable caveat in that those who depend on remittances are usually the most poor and vulnerable.

Eating Out

Counterintuitively, the crisis in West Africa has actually allowed people to keep some diversity in their diet because people are “eating out” more. Typical meals eaten at informal restaurants include some meat, some vegetables, and a larger amount of a staple food. Ironically, eating out seems to be one way people maintain diet diversity as opposed to merely accessing calories from staple foods at home.

Urban Interventions

One workshop participant voiced the concern that interventions in urban areas may actually bring more people to urban areas, seeking that intervention. Different thinking is needed to plan the delivery mechanisms for the urban poor and the rural poor, and the incentives of urban interventions should not be so attractive that they instigate an even more serious problem of urbanization than already exists.

Investment in Rural Agriculture

The belief that the international community should keep food prices artificially low as a response to the current food crisis and ongoing price volatility is controversial. The idea that lower food prices (even if they are kept artificially low) are better than higher food prices makes intuitive sense. Yet this issue needs to be considered from a dynamic perspective. The true negative aspects of the current crisis stem from the lack of investments in rural areas. Agricultural productivity has not increased, and infrastructure development has been ignored. Several workshop participants argued that because food prices were kept artificially low, agricultural investments were neglected. As a result, now a variety of social intervention programs are needed—including transfer programs and poverty relief programs. The underlying issue of a lack of investment in rural agriculture still remains.

REFERENCES

Abebe, D., and N. Singburaudom. 2006. Morphological, cultural and pathogenicity variation of exserohilum turcicum (pass) leonard and suggs isolates in maize (zea mays l.). Kasetsart Journal—Natural Science 40(2):341-352.

Action Contre la Faim. 2009. Feeding hunger and insecurity: The Global Food Price Crisis. London: Action Against Hunger..

Black, R. E., L. H. Allen, Z. A. Bhutta, L. E. Caulfield, M. de Onis, M. Ezzati, C. Mathers, and J. Rivera. 2008. Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet 371(9608):243-260.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2008. Cambodia Initiative on Soaring Food Prices. Cambodia: FAO/WFP.

———. 2009. More People Than Ever Are Victims of Hunger. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

Headey, D., and S. Fan. 2008. Anatomy of a crisis: The causes and consequences of surging food prices. Agricultural Economics 39(SUPPL. 1):375-391.

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. 2007. World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Jones, G., R. W. Steketee, R. E. Black, Z. A. Bhutta, and S. S. Morris. 2003. How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet 362(9377):65-71.

Menzel, P., and F. D’Aluisio. 2005. Hungry Planet: What the World Eats. New York: Random House, Inc.

UN. 2004. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2003 Revision. New York: United Nations.

Victora, C. G., L. Adair, C. Fall, P. C. Hallal, R. Martorell, L. Richter, and H. S. Sachdev. 2008. Maternal and child undernutrition: Consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet 371(9609):340-357.

von Braun, J., A. Ahmed, K. Asenso-Okyere, S. Fan, A. Gulati, J. Hoddinott, R. Pandya-Lorch, M. W. Rosegrant, M. Ruel, M. Torero, T. van Rheenen, and K. von Grebmer. 2008. High Food Prices: The What, Who, and How of Proposed Policy Actions. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.