Improving the Nation’s Health Care System

The United States currently spends more than $2.2 trillion annually on health care expenses, including costs borne by the government, the private sector, and individuals. In 2007, the latest year for which data are available, the nation spent on health care 16 percent of its gross domestic product, the broadest measure of economic output—a level higher than any other developed nation. Many observers argue that with this level of investment, the nation should be able to provide all of its residents with quality health care. Yet the health care system falls well short of that goal. Nearly every component of the system costs too much to operate, and the various components too often fail to work together, with the whole system becoming less than the sum of its parts. But perhaps the system’s overarching flaw is that it provides many patients with less-than-optimal care or, in some cases, no care at all. Such concerns are driving interest in health care reform from both sides of the political aisle.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) seeks ways to help reinvigorate the health care system every year. Studies range from crafting blueprints for major system overhauls to offering guidance for how health care professionals should provide care to patients, to studies on development of policies and technologies that reduce the effects of disabilities.

Creating a health care system that works well

The nation’s health care system is complex almost beyond description, with payers, providers, regulators, and patients interacting in myriad ways.

Across every sector of the system, opportunities exist to streamline operations and improve patient care.

Coping with an aging population

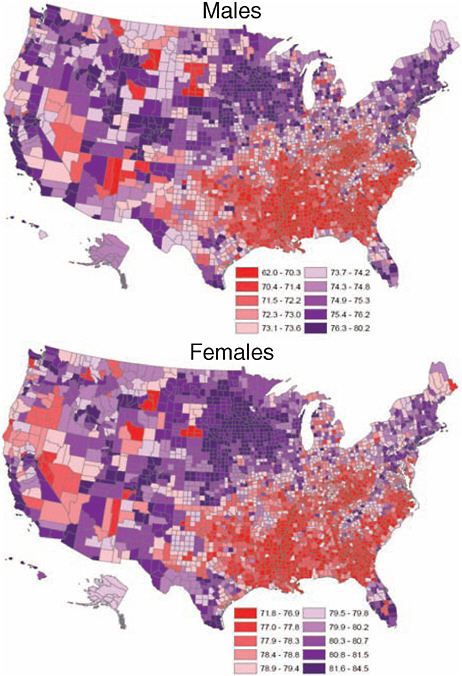

The nation is rapidly growing older. By 2030, the number of adults aged 65 and older will almost double, placing accelerating demands on the nation’s health care system. Older adults rely on health care services far more than other segments of the population. Additionally, this cohort of elderly people will be the most diverse the nation has ever seen, with greater education, increased longevity, widely dispersed families, and more racial and ethnic diversity, making their needs much different than previous generations.

With support from a number of private organizations, the IOM examined what this explosion of older people will mean for the nation and how it can prepare to meet the challenges certain to arise. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce (2008) finds that the current workforce is too small and woefully unprepared to provide an adequate level of high-quality care to this growing population group, and it calls for a series of bold initiatives—starting immediately.

Among the initiatives, a national effort is needed to train all health care providers in the basics of geriatric care. Such training may be undertaken in health professional schools and health care training programs or through other means. A national push also is needed to better prepare family members and other informal caregivers to tend to older people, as well as to prepare these individuals to take more active roles in their own care. To foster such efforts, Medicare, Medicaid, and other health plans should pay more for the services of geriatric specialists and direct-care workers to attract more health professionals and to staunch turnover among care aides, many of whom earn wages below the poverty level.

Governments at all levels, along with a spectrum of health care organizations, need to do more to disseminate innovative models of care delivery that have proved efficient and cost effective for older adults. Diffusion of such models has been minimal, often because current financing systems do not provide payment for features such as patient education, care

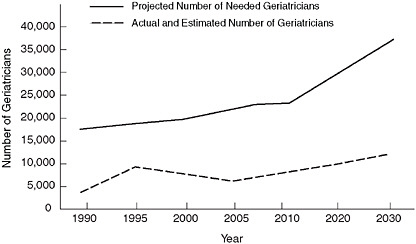

Projected number of needed geriatricians.

SOURCE: Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce, p. 20.

coordination, and interdisciplinary care. Because no single model of care will be sufficient to meet the needs of all older adults, Congress and public and private foundations should significantly increase support for research and programs that promote the development of additional innovative care models, especially in areas where effective delivery models are lacking, such as in preventive and palliative care.

The IOM accompanied the report’s release with an intensive communication outreach effort, which included, among other activities, three symposia held across the country to discuss various aspects of the report and extensive briefings of congressional leaders.

By 2030, the number of adults aged 65 and older will almost double, placing accelerating demands on the nation’s health care system.

As a direct result, in December 2008, Senator Herb Kohl (D-WI) and Representative Jan Schakowsky (D-IL) jointly introduced the Retooling the Health Care Workforce for an Aging America Act, which incorporates the report’s recommendations. According to its sponsors, the bill “aims to expand education and training opportunities in geriatrics and long-term care for licensed health professionals, direct-care workers, and family caregivers.” Both the Senate and House bills were referred to Committee in early 2009.

In another of the report’s ripple effects, a group of national organizations representing older adults, health care professionals, direct-care workers, and family caregivers joined together to form the Eldercare Workforce Alliance. Now with 29 members, the alliance is working to implement many of the IOM’s recommendations.

Restructuring medical resident training

Among the many recommendations aimed at preparing the nation for an aging baby boomer population is a clear need to address the training of future doctors. In addition to the great need to train geriatric specialists, however, the nation also must address how to better train all medical residents. As an important part of their training, recent medical school graduates must serve a residency to prepare them to practice medicine independently. During the 3 to 7 years of this training, residents often work long hours with limited time off to prevent acute and chronic sleep deprivation. Some observers argue that such duty hours may unduly fatigue residents and lead to increased risk of medical errors and accidents. Many medical educators, on the other hand, maintain that extensive duty hours are essential to provide residents with the educational experiences necessary to become competent in the complexities of diagnosing and treating patients.

At the request of Congress and with support from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the IOM evaluated current evidence on this thorny issue. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety (2009) finds considerable scientific evidence that the amount of duty hours permitted in current resident work schedules can result in fatigue and the chance of fatigue-related medical errors, and that adjustments to the duty hour limits are needed. The report does not recommend reducing the total residents’ work hours from the maximum average of 80 per week now allowed. Rather, the report recommends that the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, which sets the standard, reduce the maximum number of hours that residents can work without time for sleep to 16, down from 30 hours; increase the number of days residents must have off; and restrict moonlighting during residents’ off-hours, among other changes. The report also

Comparison of IOM Committee Adjustments to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s (ACGME’s) Current Duty Hour Limits

|

|

2003 ACGME Duty Hour Limits |

IOM Recommendation |

|

Maximum hours of work per week |

80 hours, averaged over 4 weeks |

No change |

|

Maximum shift length |

30 hours (admitting patients up to 24 hours then 6 additional hours for transitional and educational activities) |

|

|

Maximum in-hospital on-call frequency |

Every third night, on average |

Every third night, no averaging |

|

Minimum time off between scheduled shifts |

10 hours after shift length |

|

|

Maximum frequency of in-hospital night shifts |

Not addressed |

4 night maximum; 48 hours off after 3 or 4 nights of consecutive duty |

|

Mandatory time off duty |

|

|

|

Moonlighting |

Internal moonlighting is counted against 80-hour weekly limit |

|

|

Limit on hours for exceptions |

88 hours for select programs with a sound educational rationale |

No change |

|

Emergency room limits |

12-hour shift limit, at least an equivalent period of time off between shifts; 60-hour workweek with additional 12 hours for education |

No change |

|

SOURCE: Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety, p. 13. |

||

calls for greater supervision of residents by experienced physicians, limits on patient caseloads based on residents’ levels of experience and specialties, and better patient handover procedures, as well as an overlap in schedules during shift changes to reduce the chances for error during the handover of patients from one doctor to another.

During the 3 to 7 years of this training, residents often work long hours with limited time off to prevent acute and chronic sleep deprivation.

Financial costs and an insufficient health care workforce are the biggest barriers to revising resident hours. Accordingly, all financial stakeholders in graduate medical education should provide additional funding for teaching hospitals to cover the additional costs—an estimated $1.7 billion annually—associated with shifting some work from current residents to other health care personnel or additional residents. At the same time, productivity and quality gains among residents may help offset these costs. For example, a previous IOM report, Preventing Medical Errors (2006), found that the extra medical costs of treating drug-related injuries occurring in hospitals nationwide conservatively amount to $3.5 billion a year.

Improving cancer care

With nearly 1.5 million new cases of cancer expected to be diagnosed in America in 2009, the effect of the disease on the nation can hardly be overstated. Cancer impacts not only patients and their families, but also the health care workforce, and it is connected to many other challenges, from research strategies to end-of-life care, that confront society. Patients are living longer thanks to cancer care today that provides state-of-the-science biomedical treatment. But the treatments often fail to address the psychological and social problems associated with the illness—or with the treatments themselves—and patients and their families suffer in various ways.

At the request of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the IOM took an in-depth look at how cancer patients might be better served. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs (2007) concludes that care that focuses solely on eradicating tumors without taking

account of the patient’s general well-being falls short of quality care. Such incomplete care may increase a patient’s suffering and compromise his or her ability to follow through on treatment. As a remedy, the nation should adopt a new standard of care under which all oncology care providers would systematically screen patients for distress and other problems; connect patients with health care or service providers who have resources to meet these needs and coordinate care with these professionals; and periodically reevaluate patients to determine if any changes in care are indicated.

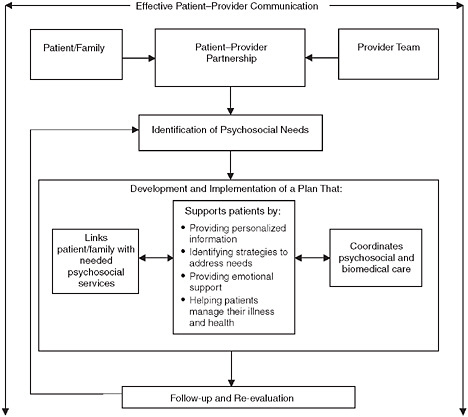

As a guide to achieving this standard, the report recommends a set of 10 actions that should be taken by oncology providers, health policy makers, educators, health insurers, health plans, quality oversight organizations, researchers and research sponsors, and consumer advocates. As one step,

Model for the delivery of psychosocial health services.

SOURCE: Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs, p. 8.

group purchasers of health care—Medicare, Medicaid, and employers—and health insurance plans should assess how psychosocial care is addressed in their agreements with each other and with health care providers, and then determine the adequacy of payment rates, adjusting them as necessary. In addition, a number of government and private organizations can encourage cancer care providers to adhere to the new standard. For example, the National Cancer Institute (NCI), as the nation’s leader in developing better approaches to cancer care, could include requirements for meeting psychosocial health needs in its protocols and programs. Standard-setting organizations, such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer, also could incorporate the new standard and its components into their own standards.

Leaders in the field were listening. At a congressional briefing in March 2008, a high-ranking official at the NCI reported that his agency has taken numerous steps to implement some of the report’s recommendations. For example, the Institute is continuing to fund “centers of excellence” in patient-centered communications; providing community cancer centers with support to conduct patient experience surveys; and pursuing a number of projects, often in collaboration with other agencies, to improve measurement of “whole patient” outcomes, with the end goal being development of a national monitoring and surveillance system.

Reducing conflicts of interest in medical research

In cancer as well as many other areas of medicine, collaborations of physicians and researchers with industry can provide valuable benefits to society, particularly in the translation of basic scientific discoveries to new therapies and products. But financial ties between medicine and industry may create conflicts of interest that put at risk the integrity of medical research, the objectivity of professional education, the quality of patient care, the soundness of clinical practice guidelines, and the public’s trust in medicine.

… the report notes that if industry and the medical community fail to strengthen their conflict-of-interest policies, practices, and enforcement, more policy makers may turn to legislative solutions, as officials in some states already have.

With support from the NIH and several private foundations, the IOM took a comprehensive look at the risks of—and possible solutions to—such conflicts. Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice (2009)

offers principles to inform the design of policies to identify, limit, and manage conflicts of interest without damaging constructive collaboration with industry. It calls for both short-term actions and long-term commitments by institutions and individuals, including leaders of academic medical centers, professional societies, patient advocacy groups, government agencies, and companies that manufacture drugs and medical devices.

Among key steps, researchers, medical school faculty, and private-practice doctors should forgo gifts of any amount from medical companies and should decline to publish or present material ghostwritten or otherwise controlled by industry. Consulting arrangements should be limited to legitimate expert services spelled out in formal contracts and paid for at a fair market rate. Physicians should limit their interactions with company sales representatives and use free drug samples only for patients who cannot afford medications. At a broader level, all academic medical centers, journals, professional societies, and other entities engaged in health research, education, clinical care, and development of practice guidelines should establish or strengthen conflict-of-interest policies.

On the other side of the coin, Congress should require pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and device firms to report through a public website the payments they make to doctors, researchers, academic health centers, professional societies, patient advocacy groups, and others involved in medicine. Such a public record could serve as a deterrent to inappropriate relationships and undue industry influence, and would provide medical institutions with a way to verify the accuracy of information that physicians, researchers, and senior officials have disclosed to them.

Although the report calls for some new legislation and regulations, it emphasizes the role of voluntary efforts by the various stakeholders, stressing that voluntary action is more likely to reinforce professional values and foster policies that minimize unintended consequences and administrative burdens. But the report notes that if industry and the medical community fail to strengthen their conflict-of-interest policies, practices, and enforcement, more policy makers may turn to legislative solutions, as officials in some states already have.

Conflict of Interest Report Recommendations in Overview

|

Recommendation Number and Topic |

Primary Actors |

|

General policy |

|

|

3.1 Adopt and implement conflict of interest policies |

Institutions that carry out medical research and education, clinical care, and clinical practice guideline development |

|

3.2 Strengthen disclosure policies |

Institutions that carry out medical research and education, clinical care, and clinical practice guideline development |

|

3.3 Standardize disclosure content and formats |

Institutions that carry out medical research and education, clinical care, and clinical practice guideline development and other interested organizations (e.g., accrediting bodies, health insurers, consumer groups, and government agencies) |

|

3.4 Create a national program for the reporting of company payments |

U.S. Congress; pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotechnology companies |

|

Medical research |

|

|

4.1 Restrict participation of researchers with conflicts of interest in research with human participants |

Academic medical centers and other research institutions; medical researchers |

|

Medical education |

|

|

5.1 Reform relationships with industry in medical education |

Academic medical centers and teaching hospitals; faculty, students, residents, and fellows |

|

5.2 Provide education on conflict of interest |

Academic medical centers and teaching hospitals; professional societies |

|

5.3 Reform financing system for continuing medical education |

Organizations that created the accrediting program for continuing medical education and other organizations interested in high-quality, objective education |

|

Medical practice |

|

|

6.1 Reform financial relationships with industry for community physicians |

Community physicians; professional societies; hospitals and other health care providers |

|

6.2 Reform industry interactions with physicians |

Pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotechnology companies |

|

Recommendation Number and Topic |

Primary Actors |

|

Clinical practice guidelines |

|

|

7.1 Restrict industry funding and conflicts in clinical practice guideline development |

Institutions that develop clinical practice guidelines |

|

7.2 Create incentives for reducing conflicts in clinical practice guideline development |

Accrediting and certification bodies, formulary committees, health insurers, public agencies, and other organizations with an interest in objective, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines |

|

Institutional conflict of interest policies |

|

|

8.1 Create board-level responsibility for institutional conflicts of interest |

Institutions that carry out medical research and education, clinical care, and clinical practice guideline development |

|

8.2 Revise Public Health Service regulations to require policies on institutional conflicts of interest |

National Institutes of Health |

|

Supporting organizations |

|

|

9.1 Provide additional incentives for institutions to adopt and implement policies |

Oversight bodies and other groups that have a strong interest in or reliance on medical research, education, clinical care, and practice guideline development |

|

9.2 Develop research agenda on conflict of interest |

NIH, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and other agencies of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

|

SOURCE: Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice, p. 16. |

|

Advancing the national health agenda

As policy makers work to create a blueprint for health care in the years ahead, they must consider both establishing new policies and programs and reforming those that do not function well. A recent IOM report, HHS in the 21st Century: Charting a New Course for a Healthier America (2008), described earlier in this book, suggests ways in which the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) can be improved. Subsequent work by the IOM discusses other strategies for improving the nation’s care.

As part of a universal effort to bring down health care costs in the United States while improving the quality of the care provided, Congress requested in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act that the IOM conduct a study to determine the appropriate national priorities for comparative effectiveness research.

The medical field depends on the trust placed by patients in their doctors and in their doctors’ advice about treatment and care. Yet often, physicians and patients must make decisions in the absence of complete information because the evidence is lacking for the effectiveness of one approach compared to another. Comparative effectiveness research offers the opportunity to demonstrate the effectiveness of one strategy over another for a certain condition, enabling doctors and patients to make smarter health decisions founded in sound scientific evidence. One of the fundamental aims of comparative effectiveness research is to help doctors avoid ineffective or more costly approaches that might not work or, worse, allow a patient’s condition to deteriorate by delaying more effective treatment.

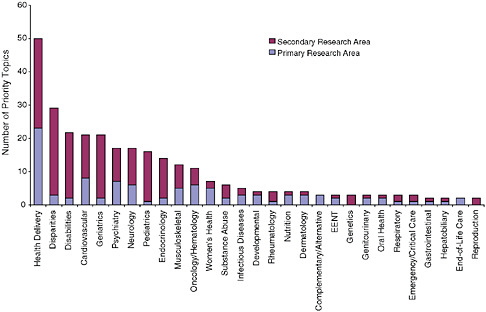

The IOM report, Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research (2009), provides 100 top priorities for comparative effectiveness research. These priorities should play into decisions regarding the $400 million appropriated for comparative effectiveness research in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

Embracing health information technologies

The old adage “knowledge is power” may apply especially to health care. Yet many sectors of the health care system have been slow to embrace information technologies. In a recent report, for example, the American Hospital Association found that only 11 percent of hospitals had fully implemented use of electronic health records, while another 57 percent had partially implemented their use. To help foster progress in applying information technology to health care, the HHS in 2004 established the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) and set a 10-year goal for creating the Nationwide Health Information Network. For guidance on its efforts to advance its health agenda, HHS turned to the IOM.

Distribution of the recommended research priorities by primary and secondary research areas.

SOURCE: Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research, p. 101.

The IOM’s Board on Health Care Services, in collaboration with the National Research Council’s Computer Science and Telecommunications Board, examined the cohesiveness and pace of the HHS program, focusing in particular on efforts to develop and implement operating standards. Opportunities for Coordination and Clarity to Advance the National Health Information Agenda: A Brief Assessment of the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology: A Letter Report (2007) finds a number of shortcomings in current efforts and points to needed improvements.

In sum, the study committee was unable to make a straightforward assessment of the pace of activities, in large part because the ONC had not set forth a clear and complete set of milestones against which such an assessment could be made. The report notes that some observers believe the process (from the selection of use cases to standards acceptance) is proceeding too slowly, while others believe it is going too quickly. These views reflect varying perceptions about the standards processes as a whole as well as concerns about whether a uniform pace is appropriate for all activities.

The report advises the head of the ONC to develop a strategic plan—as required by the Executive Order that established the office—providing a roadmap with specific objectives, milestones, and metrics for the national health information technology agenda. The ONC also should clarify how it will accomplish its aims, focusing specifically on processes for making program decisions, for managing workflow, for coordinating efforts within the program and with other groups, and for obtaining feedback and incorporating it into program operations. These steps can help capitalize on the promise that information technology holds for improving the nation’s health.

Exploring the prospects of integrative medicine

At a time when attention has turned to health reform and the future shape of health care, many are considering the promise of “integrative medicine.” Integrative medicine can be described as orienting the health care process to engage patients and caregivers in the full range of physical, psychological, social, preventive, and therapeutic factors known to be effective and necessary for the achievement of optimal health.

With support from The Bravewell Collaborative, the IOM convened the Summit on Integrative Medicine and the Health of the Public in February 2009 to explore the science and practice of integrative medicine for improving the breadth and depth of patient-centered care and promoting the nation’s health. During the meeting, participants reviewed the state of the science, assessed the potential and the priorities, and began to suggest elements of an agenda to help improve the prospects for integrative medicine’s contributions to better health and health care. Speakers and attendees also discussed the ways in which integrative medicine seeks to encourage the personal and community environments that shape and empower patients’ knowledge, skills, and support to be active participants in their own care.

Ensuring that those who need care can receive care

The nation’s health care system not only must be efficient and deliver high-quality services. The system also must be properly structured and complemented by a range of other government policies in order to ensure that everyone has ready and equal access to health services.

Seeking solutions for the nation’s uninsured crisis

The growing number of uninsured Americans—totaling 45.7 million as of 2007—is taking a toll on the nation’s health. One in 5 adults under age 65 and nearly 1 in 10 children are uninsured. Uninsured individuals experience much more risk to their health than insured individuals.

Between 2001 and 2004, the IOM issued six reports on the consequences of being uninsured and offering a uniform recommendation—namely, that the nation quickly implement a strategy to achieve health insurance coverage for all. With support from The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the IOM returned to this issue in 2008 and produced an up-to-date assessment of the research evidence regarding insurance coverage. America’s Uninsured Crisis: Consequences for Health and Health Care (2009) finds that a chasm remains between the health care needs of people without health insurance and access to effective health care services. This gap results in needless illness, suffering, and death.

The evidence shows more clearly than ever that having health insurance is essential for people’s health and well-being, and safety-net services are not enough to prevent avoidable illness, worse health outcomes, and premature death. Moreover, new research suggests that when local rates of uninsurance are relatively high, even people with insurance are more likely to have difficulty obtaining needed care and to be less satisfied with the care they receive. Without concerted attention from all stakeholders, these problems will only grow worse as the current economic crisis and associated growth in unemployment fuel further decline in the number of people with health insurance and intensify financial pressures on local health care delivery.

The growing number of uninsured Americans—totaling 45.7 million as of 2007—is taking a toll on the nation’s health. One in 5 adults under age 65 and nearly 1 in 10 children are uninsured.

Reducing health disparities and promoting health literacy

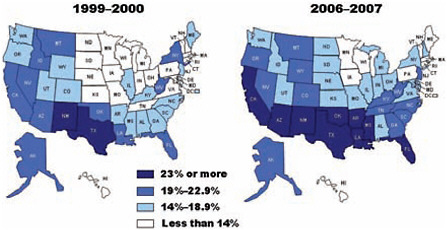

For many of those who do have health insurance, proper health care remains a fantasy more than reality. Although the health status for many U.S. resi-

Comparison in the percentage of nonelderly adults without health insurance, by state, 1999–2000 and 2006–2007.

SOURCE: America’s Uninsured Crisis: Consequences for Health and Health Care, p. 14.

dents has improved steadily, some racial and ethnic groups—including African Americans, Hispanics, Native Americans, Alaskan Natives, Asians, and Pacific Islanders—find themselves excluded from such progress. Members of these groups more frequently develop diseases such as cancer, HIV infection and AIDS, cardiovascular disease, asthma, stroke, and diabetes, and their infants suffer higher rates of mortality. Across these groups, tens of millions of people experience health levels, as measured in terms of life expectancy, that are more typical of those in developing countries.

The IOM’s Roundtable on Health Disparities convened a workshop to increase the visibility of racial and ethnic health disparities as a national problem, further the development of programs and strategies to reduce disparities, and foster leaders who can advance the field. Challenges and Successes in Reducing Health Disparities: Workshop Summary (2008) presents the experiences of health professionals and other care workers who serve on the front lines of efforts to reduce disparities in health care, as well as the experiences of researchers, policy makers, community activists, and other individuals who deal with the array of social factors that help determine a person’s overall health.

Based on their various experiences, some participants called for increased efforts at the national level to collect solid data about health disparities and eliminate institutional racism. Other participants focused on

the local level, suggesting, for example, that communities develop the capacity to gather their own health, social, and economic data, rather than rely on standard indicators alone. In this way, communities will be able to track the health status of their members over time, enabling them to call for help from state or national organizations as needed to correct any health problems that emerge.

As the nation has experienced vast demographic changes, especially over the past generation as waves of immigrants dispersed across the country and formed new communities, new challenges have emerged in the way the health care system delivers services. Health care providers now must tailor their efforts to each individual, reflecting that person’s culture and languages. The aim is to ensure that all patients receive the same quality of care and that they have adequate knowledge and understanding of health issues and services to make appropriate decisions about their care.

This transformation has incidentally elevated health care disparities and health literacy as major health care topics. Three IOM bodies—the Forum on the Science of Health Care Quality Improvement and Implementation, the Roundtable on Health Disparities, and the Roundtable on Health Literacy—jointly convened a workshop in 2008 to discuss these concerns. Toward Health Equity and Patient-Centeredness: Integrating Health Literacy, Disparities Reduction, and Quality Improvement: Workshop Summary (2009) explores the various steps that health professionals and others are taking to improve care delivery to today’s populations and what challenges remain in assuring better health for future populations.

Workshop participants, drawn from a range of fields across the health care spectrum, examined how providing patients with appropriate medications in their primary languages and offering translation services can vastly improve the health care patients receive, and they considered ways in which health care providers might integrate these seemingly separate challenges into their daily routines. Participants discussed how providers can best manage available resources and how they can teach health literacy over the life course of their patients. They also considered how improvements at the national level in areas such as data collection and workforce training can positively affect health care and improve health outcomes.

Largest Disparities in Health Care Quality for Selected Groups: 2005 Versus 2007 NHDRa

|

Group |

2005 NHDRa |

2007 NHDRa |

||

|

Measure |

Relative Rate |

Measure |

Relative Rate |

|

|

Black |

New AIDS cases per 100,000 population age 13 and over |

10.4 |

New AIDS cases per 100,000 population age 13 and over |

10.0 |

|

|

Hospital admissions for pediatric asthma per 100,000 population ages 2–17 |

4.0 |

Hospital admissions for pediatric asthma per 100,000 population ages 2–17 |

3.8 |

|

|

Percent of patients who left the emergency department without being seen |

1.9 |

Hospital admissions for lower extremity amputations in patients with diabetes per 100,000 population |

3.8 |

|

Asian |

Persons age 18 or older with serious mental illness who did not receive mental health treatment or counseling in the past year |

1.6 |

Composite: Adults who reported poor communication with health providers |

1.6 |

|

|

Adults who can sometimes or never get care for illness or injury as soon as wanted |

1.6 |

Long-stay nursing home residents who were physically restrained |

1.5 |

|

|

Adults age 65 and over who did not ever receive pneumococcal vaccination |

1.5 |

Adults age 65 and over who did not ever receive pneumococcal vaccination |

1.5 |

|

AI/ANb |

Women not receiving prenatal care in the first trimester |

2.1 |

Women not receiving prenatal care in the first trimester |

2.1 |

|

|

Composite: Adults who reported poor communication with health providers |

1.8 |

Composite: Adults who reported poor communication with health providers |

1.8 |

|

Group |

2005 NHDRa |

2007 NHDRa |

||

|

Measure |

Relative Rate |

Measure |

Relative Rate |

|

|

|

Children ages 2–17 with no advice about physical activity |

1.3 |

Women age 40 and over who reported they did not have a mammogram within the past 2 years |

1.8 |

|

Hispanic |

New AIDS cases per 100,000 population age 13 and over |

3.7 |

New AIDS cases per 100,000 population age 13 and over |

3.5 |

|

|

Adults who can sometimes or never get care for illness or injury as soon as wanted |

2.0 |

Hospital admissions for lower- extremity amputations in patients with diabetes per 100,000 population |

2.9 |

|

|

Composite: Children whose parents reported poor communication with their health providers |

1.8 |

Women not receiving prenatal care in the first trimester |

2.0 |

|

Poor |

Composite: Children whose parents reported poor communication with their health providers |

3.3 |

Composite: Children whose parents reported poor communication with their health providers |

3.0 |

|

|

Adults who can sometimes or never get care for illness or injury as soon as wanted |

2.3 |

Adults who can sometimes or never get care for illness or injury as soon as wanted |

2.4 |

|

|

Children ages 2–17 who did not have a dental visit |

2.0 |

Women age 40 and over who reported they did not have a mammogram within the past 2 years |

2.1 |

|

aNHDR = National Healthcare Disparities Report. bAI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native. SOURCE: Toward Health Equity and Patient-Centeredness: Integrating Health Literacy, Disparities Reduction, and Quality Improvement: Workshop Summary, p. 10. |

||||