Taking Care of Those Who Take Care of Us: Military and Veterans

The men and women in the United States armed forces confront health challenges of a scope and complexity that few other Americans ever experience. Active-duty personnel in combat directly face risks of injury or death. In addition, both combat forces and personnel serving away from the front lines may experience lengthy exposures to hazardous environments, either natural or produced by human activities. Chemical exposures, for example, may at times exceed those that would be considered safe in a civilian working environment. Beyond immediate physical threats, military personnel often must deal with the effects of being in high-intensity, stressful, and dangerous environments, sometimes for months or years at a time.

The Department of Defense (DoD) bears the primary responsibility for keeping troops fit for service, protecting service men and women from preventable risks, and providing them with high-quality health care. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provides health care to service members after they leave the military. In order to help fulfill these missions, the DoD and the VA regularly turn to the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to study and recommend actions on a range of health-related issues.

Assessing the health effects of the Gulf War

In 1991, nearly 700,000 U.S. troops, including many members of the reserve and National Guard, took part in the Persian Gulf War. On returning home, a substantial number of military personnel reported health problems that

they believed to be connected to their service. At the request of Congress, the IOM has conducted a series of studies that examine the scientific and medical evidence on the health effects of the various agents to which military personnel may have been exposed during the Gulf War. The IOM more recently expanded its focus to include studies on the health effects experienced by military personnel involved in the war in Afghanistan, which began in 2001, and the war in Iraq, which began in 2003.

The IOM published the first volume in the Gulf War and Health series in 2000. It assesses the health effects of exposure to a variety of chemicals, including depleted uranium and the warfare agent sarin, as well as the health effects that may be related to use of pyridostigmine bromide and vaccines, including the botulinum toxoid and anthrax vaccines. (An update to this report, focused specifically on sarin, was released in 2004.) The second volume in the series, published in 2003, examines the health effects associated with exposure to pesticides and solvents. The third volume, published in 2005, analyzes the long-term human health effects associated with exposure to selected environmental agents, pollutants, and other synthetic chemical compounds, such as fuels and propellants. The fourth volume, published in 2006, examines the state of veterans’ health in the years since the conflict, rather than specific potential causes of health problems. The fifth volume, published in 2007, examines the long-term health effects associated with various infectious diseases that Gulf War veterans—as well as veterans of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars—may have faced.

Evaluating the effects of combat stress

The sixth volume in the series focuses on health effects linked to the stresses of serving in a combat zone. By definition, war zones are stressful places. Troops face concerns about surviving, being taken prisoner, or being tortured. They may see friends die or become maimed, and they may have to handle dead bodies. Less traumatic but more pervasive stressors include anxiety about home life, such as loss of a job and income, impacts on relationships, and absence from family.

Gulf War and Health, Volume 6: Physiologic, Psychologic, and Psychosocial Effects of Deployment-Related Stress (2007) finds that military personnel who serve in war zones face a greater risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), other anxiety disorders, and depression than do personnel who are not deployed. They also are more likely to experience

alcohol abuse, accidental death, suicide, and marital and family conflict, including domestic violence, within the first few years after leaving the war zone. In addition, drug abuse, unexplained illnesses, chronic fatigue syndrome, gastrointestinal symptoms, skin diseases, fibromyalgia, chronic pain, and an increased likelihood of being incarcerated may be associated with the stresses of being in a war, although the evidence to support these links is weaker. The findings are based not only on studies of Gulf War veterans, but also on studies of veterans from World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The report notes that it is not yet possible to offer definitive answers about the connections between many health problems and the stresses of war, in part because the military does not routinely assess service members’ physical, mental, and emotional status before deployment. This knowledge gap is taking on increased importance as the United States continues its military operations in Iraq and expands them in Afghanistan. To help bridge the gap, the DoD should conduct comprehensive, standardized evaluations of service members’ medical conditions, psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses, and psychosocial status and trauma history before and after they deploy to war zones. Such screenings would provide baseline data for comparisons and information to determine the long-term consequences of deployment-related stress. In addition, they would help identify at-risk personnel who might benefit from targeted intervention programs, such as marital counseling or therapy for psychiatric or other disorders, during deployment, and they would help the DoD and the VA choose which intervention programs to implement for veterans adjusting to post-deployment life. A separate IOM study, described later in this chapter, specifically discusses treatment of PTSD.

Evaluating the effects of brain injury

War is damaging in any form, but the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have brought new types of weaponry and methods of attack that have proved increasingly dangerous. In particular, these conflicts are seeing expanded use of more powerful explosive devices that are causing more severe types of blast injuries, especially traumatic brain injury. Indeed, traumatic brain

|

Summary of Findings Regarding the Association Between Deployment to a War Zone and Specific Health and Psychosocial Effects Sufficient Evidence of a Causal Association Evidence from available studies is sufficient to conclude that there is a causal relationship between deployment to a war zone and a specific health outcome in humans. The evidence is supported by experimental data and fulfills the guidelines for sufficient evidence of an association (below). The evidence must be biologically plausible and satisfy several of the guidelines used to assess causality, such as strength of association, dose-response relationship, consistency of association, and temporal relationship.

Sufficient Evidence of an Association Evidence from available studies is sufficient to conclude that there is a positive association. That is, a consistent positive association has been observed between deployment to a war zone and a specific health outcome in human studies in which chance and bias, including confounding, could be ruled out with reasonable confidence. For example, several high-quality studies report consistent positive associations, and the studies are sufficiently free of bias and include adequate control for confounding.

Limited but Suggestive Evidence of an Association Evidence from available studies is suggestive of an association between deployment to a war zone and a specific health outcome, but the body of evidence is limited by the inability to rule out chance and bias, including confounding, with confidence. For example, at least one high-quality study reports a positive association that is |

|

sufficiently free of bias, including adequate control for confounding, and other corroborating studies provide support for the association (corroborating studies might not be sufficiently free of bias, including confounding). Alternatively, several studies of lower quality show consistent positive associations, and the results are probably not due to bias, including confounding.

Inadequate/Insufficient Evidence to Determine Whether an Association Exists Evidence from available studies is of insufficient quantity, quality, or consistency to permit a conclusion regarding the existence of an association between deployment to a war zone and a specific health outcome in humans.

|

|

Limited/Suggestive Evidence of No Association Evidence from well-conducted studies is consistent in not showing a positive association between exposure to a specific agent and a specific health effect after exposure of any magnitude. A conclusion of no association is inevitably limited to the conditions, magnitudes of exposure, and length of observation in the available studies. The possibility of a very small increase in risk after exposure studied cannot be excluded.

SOURCE: Gulf War and Health, Volume 6: Physiologic, Psychologic, and Psychosocial Effects of Deployment-Related Stress, p. 8. |

injury has come to be the signature wound of the war in Iraq, with more than 5,500 soldiers suffering such injury as of early 2008.

Gulf War and Health, Volume 7: Long-Term Consequences of Traumatic Brain Injury (2008) finds that military personnel who suffer moderate or severe degrees of such injuries face an increased risk for developing several health problems at some time in their lives. These problems include symptoms similar to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, aggression, memory loss and impaired concentration, depression, and diminished abilities to maintain social relationships. Some personnel who suffer even mild traumatic brain injury also experience some of these health consequences, including increased risk for aggressive behavior, depression, and memory and concentration problems. Traumatic brain injury may cause other adverse consequences as well, such as vision problems and seizures, a particular type of diabetes, psychosis, and suicide, though there is not sufficient evidence to make definitive conclusions.

… traumatic brain injury has come to be the signature wound of the war in Iraq, with more than 5,500 soldiers suffering such injury as of early 2008.

The report emphasizes the need to develop a fuller picture of the effects of traumatic brain injuries and other blast injuries. Toward this end,

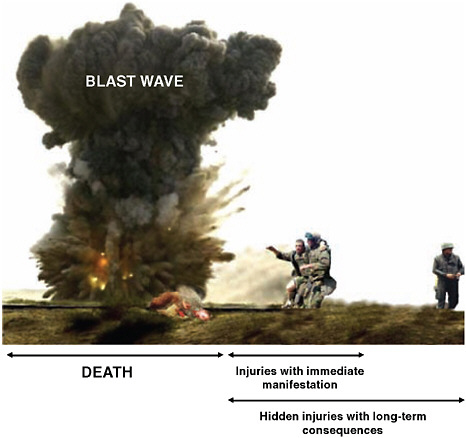

Potential consequences of blast exposure.

SOURCE: Gulf War and Health, Volume 7: Long-Term Consequences of Traumatic Brain Injury, p. 30.

the DoD should make use of several available diagnostic and evaluative tools to study every soldier who has a history of blast exposure, even of low intensity. It also should conduct predeployment neurocognitive tests of all military personnel to establish a baseline for identifying postinjury consequences, and it should conduct postdeployment neurocognitive testing of representative samples of military personnel, including those who have and have not suffered traumatic brain injury. In addition, the VA should include uninjured service members and other comparison groups in the Traumatic Brain Injury Veterans Health Registry that the agency is developing.

The DoD and the VA also should work with the broader research community to develop new or improved clinical and animal testing meth

ods to answer an array of questions. One area of interest, for example, centers on determining the long-term effects of brain injuries sustained as a result of exposure to the force of an explosion without a direct strike to the head—one of the most common perils for soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan. Problems stemming from such injuries currently may be underdiagnosed, and wounded service members may be losing valuable time for therapy and rehabilitation.

Congress has begun to take note. Shortly after the report’s release, Senator Patty Murray (D-WA), a senior member of the Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, issued a statement calling for increased screening and research related to traumatic brain injury and declaring her intention to work with the Obama administration “to implement the recommendations outlined by the Institute of Medicine.”

In other follow-on activities, the IOM and the National Academy of Engineering convened a workshop to discuss potential tools and techniques for improving the care of patients with traumatic brain injury. Participants, including both engineering and health experts, considered ways to better design care practices for service members treated at multiple institutions within the military, the VA, and the civilian sector.

Evaluating the health effects of depleted uranium

The Gulf War marked the first time that the U.S. military made extensive use of depleted uranium, using it to strengthen tank armor and to increase the penetrating ability of tank munitions. The military continues to use depleted uranium for such purposes in the Iraq war. Depleted uranium is a by-product of the uranium enrichment process used to generate fuel for nuclear power plants. It is abundant and inexpensive, and its chemical and physical properties give it added strength and a high melting point—valuable traits for military use. However, although depleted uranium is less potent than natural uranium, it still emits a significant amount of radiation, and the IOM has conducted several recent studies to better understand the risks that military personnel may face from such exposure.

In 2000, when the IOM issued its initial report on depleted uranium and various other chemical agents, few studies of health outcomes of such exposure had been conducted. The report concluded that there was inadequate or insufficient evidence to determine whether an association exists between uranium exposure and 14 types of adverse health outcomes that were considered possible. Since then, however, the results of additional

studies have become available, including studies specifically on exposure to depleted uranium, and the VA asked the IOM to update its review.

Gulf War and Health: Updated Literature Review of Depleted Uranium (2008) finds that the evidence is still inadequate or insufficient to determine whether an association exists between exposure to depleted uranium and all of the health outcomes examined. This list includes lung cancer, leukemia, lymphoma, bone cancer, renal cancer, bladder cancer, brain cancer, stomach cancer, prostate cancer, testicular cancer, reproductive or developmental dysfunction, nonmalignant respiratory disease, gastrointestinal disease, and immune-mediated disease, among others.

During the Gulf War, an estimated 134 to 164 people experienced high levels of exposure to depleted uranium, and hundreds or thousands more may have experienced lower exposure through inhalation of contaminated dust particles or ingestion via hand-to-mouth contact with contaminated clothing or other items.

Given the many remaining health unknowns, the IOM, at the request of Congress, also explored how epidemiologic studies of veterans might best be conducted to determine the health effects of exposure to depleted uranium on soldiers and on any of their children born after their exposure. Soldiers may be exposed to depleted uranium through a variety of means, including being close to tanks that are attacked and burned, participating in clean-up and salvage operations, or being caught in friendly fire incidents, among others. During the Gulf War, an estimated 134 to 164 people experienced high levels of exposure to depleted uranium, and hundreds or thousands more may have experienced lower exposure through inhalation of contaminated dust particles or ingestion via hand-to-mouth contact with contaminated clothing or other items.

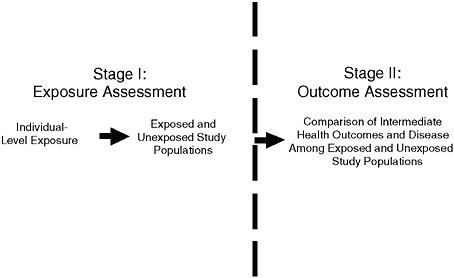

Epidemiologic Studies of Veterans Exposed to Depleted Uranium: Feasibility and Design Issues (2008) concludes that it would be difficult to carry out a comprehensive study with currently available data. Rather, the best option would be to conduct a prospective cohort study if future military operations involve exposure of large numbers of service members to depleted uranium. To detect a statistically significant increase in risk of developing lung cancer, a relatively common cancer, such a study may require following more than 1 million people who become exposed. The success of such studies also will depend on the DoD’s ability to collect accurate and complete individual-level exposure information on military personnel who enter a war theater in which depleted-uranium munitions

Stages of an epidemiologic study of depleted uranium exposure.

SOURCE: Epidemiologic Studies of Veterans Exposed to Depleted Uranium: Feasibility and Design Issues, p. 7.

and armor are used. In addition, while preparing to conduct such studies, the DoD should work with the research community to advance animal tests and other laboratory methods that may help in expanding the current knowledge base.

Tracking the health effects of Agent Orange

From 1962 to 1971, the U.S. military sprayed herbicides, including a compound called Agent Orange, over Vietnam to strip the thick jungle canopy that could conceal opposition forces, to destroy crops that those forces might depend on, and to clear tall grasses and bushes from the perimeters of U.S. base camps and outlying fire-support bases. Following the war, many veterans and their families began attributing various chronic and life-threatening diseases to exposure to Agent Orange or to dioxin (a contaminant found in the mixture), and in 1991 Congress directed the IOM to study the claims. Veterans and Agent Orange: Health Effects of Herbicides Used in Vietnam (1994) provided the first comprehensive, unbiased review of the scientific evidence regarding links between such exposure and vari

ous adverse health effects, including cancer, reproductive and developmental problems, and neurobiological disorders. Since then, the IOM has published a series of biennial updates. Collectively, these reports provide the scientific basis on which the VA awards disability compensation to Vietnam veterans. The reports also recommend research that could provide more definitive conclusions about possible health effects.

Even as the IOM carried out its series of studies, one key factor that helps determine health risk remained poorly understood—that is, comprehensive information was lacking about the levels of Agent Orange and other herbicides to which military personnel serving in Vietnam were exposed. To fill this need, a group of academic researchers developed a computer model that characterizes soldiers’ exposure based on their proximity to herbicide spraying. Put simply, the model links data on where the military sprayed herbicides with information about troop locations, and then uses the “proximity-based” data to calculate troop exposure levels. But questions have remained about the model’s accuracy and reliability, and the VA asked the IOM to analyze the model in order to determine its value, strengths, and limitations.

The Utility of Proximity-Based Herbicide Exposure Assessment in Epidemiological Studies of Vietnam Veterans (2008) finds that, in general, the model offers a promising way to extend knowledge about the effects of herbicides on the health of veterans. The model has certain shortcomings, as does the overall proximity-based approach as a surrogate for determining exposure levels. But the improved ability that the model offers in classifying herbicide exposure, and the application of that information to studies of veterans’ health, has value because of its potential to enhance understanding of the health experience of this population.

The report recommends conducting studies using the model, but it also identifies challenges in applying it and additional research that may strengthen it. For example, conducting epidemiologic studies using the exposure assessment model requires data on when and where each veteran served in Vietnam and on the veteran’s health outcomes. But the processes involved in obtaining data on individuals’ unit assignments and unit locations are administratively

difficult, time consuming, and costly, and the report calls on the VA to work with the DoD and the National Archives and Records Administration to facilitate use of military records in future studies. Even as such studies proceed, however, the VA and other federal agencies should ensure that they be accompanied by other research efforts—including the exploration of other possible exposure models—aimed at reducing the scientific uncertainty about the health of Vietnam veterans.

Fostering the well-being of military personnel

As part of its charge, the U.S. military must protect the health and well-being of its personnel—and their families—in ways that extend beyond bearing arms.

Assessing dietary supplements

Members of the military, like civilians, increasingly are using dietary supplements. Although some supplements may provide benefits to health, others may compromise the readiness and performance of service members. The risks may be greatest for specific military populations, such as members of Special Forces units, who often endure harder tasks and harsher environments and therefore face heightened physiological demands.

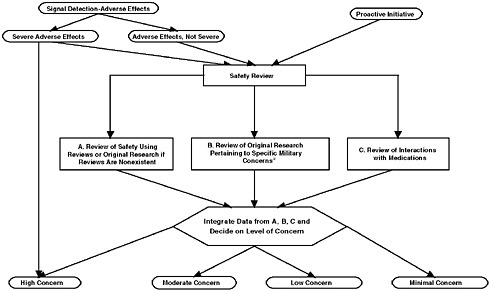

The military does not have integrated service-wide policies to guide service members or their commanders on how to use dietary supplements safely. To fill this gap, the DoD and several other public agencies and private groups turned to the IOM. Use of Dietary Supplements by Military Personnel (2008) recommends that the military adopt a systematic approach that encompasses three primary strategies: developing a system for monitoring the use of dietary supplements by military personnel, charting a framework for determining which dietary supplements pose the greatest potential problems, and devising a system that soldiers and others and can use to report adverse events associated with dietary supplements. The report also encourages the DoD to appoint an oversight committee or organization to oversee these activities and ensure their performance.

The military does not have integrated service-wide policies to guide service members or their commanders on how to use dietary supplements safely.

Framework to review the safety of dietary supplements.

aHigh physical activity, calorie restriction, hydration, gastrointestinal tract (diarrhea/nausea), liver health/function (xenobiotic clearance), cardiovascular health, mood/behavior altering, alertness/drowsiness, extreme heat/cold, injury/bleeding.

SOURCE: Use of Dietary Supplements by Military Personnel, p. 7.

In implementing this approach, several activities will be key. Information gathering and sharing must be improved. The various military services should, among other things, continue their periodic surveys, but also conduct additional surveys at selected military bases about dietary supplement use among service members who might face heightened health risks due to their tasks or environment. The services also should increase their educational and outreach efforts to provide soldiers and their families, unit commanders, and health care personnel with accurate, up-to-date information about the effects of dietary supplements and the importance of reporting any adverse effects that result from their use.

Reducing tobacco use

Fewer than 20 percent of Americans use tobacco, but more than 30 percent of active-duty military personnel do. Tobacco use not only endangers individual health, but among military populations, it impairs readiness by reducing

physical fitness, visual acuity, and sometimes hearing. Adding to concerns, the increased incidence of tobacco use among service members carries over into civilian life, with about 22 percent of veterans using tobacco.

The DoD and the armed services have set goals and taken some actions to become tobacco free, and the VA has a long history of attempting to reduce smoking among veterans. But problems remain, and the DoD and the VA asked the IOM to review their efforts and recommend improvements. Combating Tobacco Use in Military and Veteran Populations (2009) recommends that the DoD and the VA increase the priority they place on reducing tobacco use and back up this commitment by implementing state-of-the-art programs to achieve tobacco-free military and veteran populations. These programs should be run according to a strategic plan with an established time line, enforced by an engaged leadership, supported by adequate resources, and implemented by effective and enforceable policies.

As one key guideline, the report says that achieving a tobacco-free military begins by limiting the number of new tobacco users entering the military and by promoting cessation programs to ensure abstinence. Using a phased approach, the military academies and officer training programs in both universities and the military should become tobacco free first, followed by newly enlisted recruits, and finally by all other active-duty personnel. As an important part of this effort, Congress should change its policy that requires the military to sell tobacco products at reduced prices in its commissaries and exchanges, with the ultimate goal being to prohibit tobacco sales entirely at these outlets. Congress also should repeal its requirement that the VA provide designated smoking areas at its health care facilities, as such provisions have precluded the VA from going entirely tobacco free.

Fewer than 20 percent of Americans use tobacco, but more than 30 percent of active-duty military personnel do.

Identifying the best ways to treat posttraumatic stress disorder

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the most commonly diagnosed service-related mental disorder among military personnel returning from Iraq

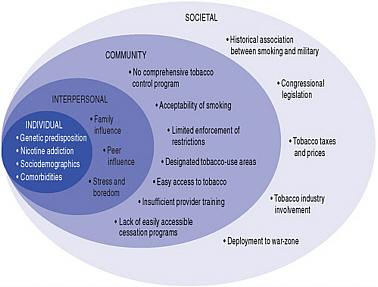

Some of the socioecologic influences on tobacco use among the military and veteran populations.

SOURCE: Combating Tobacco Use in Military and Veteran Populations, p. 82.

and Afghanistan. Surveys indicate that an estimated 12.6 percent of those who fought in Iraq and 6.2 percent of those who fought in Afghanistan have experienced PTSD. Significant numbers of Vietnam veterans and veterans of earlier conflicts also report suffering from PTSD.

Although clinicians now use several drug regimens and psychotherapeutic interventions to treat PTSD, the effectiveness of these therapies remains in question. Many observers suggest that the bulk of the studies have significant scientific shortcomings, and as a result they do not provide a clear picture of what does and does not work. At the request of the VA, the IOM reviewed the literature in an attempt to bring matters into better focus and to identity needed actions.

Treatment of PTSD: An Assessment of the Evidence (2007) concludes that because of shortcomings in many of the studies, there is not enough reliable evidence to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of most treatments. However, there is sufficient evidence to conclude that exposure therapies, such as exposing individuals to a real or surrogate threat in

a safe environment to help them overcome their fears, are effective. This finding is not meant to suggest that only exposure therapies should be used to treat PTSD and that other treatments should be discontinued. Rather, the review underscores the urgent need for additional high-quality studies that can assist clinicians in providing the best possible care to veterans and others who suffer from this serious disorder. The report offers a series of recommendations that the VA and others can use to build an effective research program. It also calls on Congress to ensure that the VA and other federal agencies have adequate resources to fund quality research on treatment of PTSD and that all stakeholders—including veterans—are represented in research planning.

Surveys indicate that an estimated 12.6 percent of those who fought in Iraq and 6.2 percent of those who fought in Afghanistan have experienced PTSD.

Evaluating military medical ethics

Military health professionals play a key role in ensuring the welfare of the service members—and, in some cases, the nonmilitary detainees—they treat. But these professionals sometimes may face ethical conflicts that arise from their responsibilities to their patients and their duties as military officers integrally involved in military operations.

To examine these ethical challenges and explore ways to meet such conflicts and gain optimal results, the IOM held a workshop that brought together stakeholders from a variety of fields, including the military, the health care community, universities, and human rights groups. The workshop proceeded from the premise that military ethical conflicts are best brought to light and discussed by military and civilian leaders rather than relegated to individuals to cope with them alone in situations of stress. To hone discussions, workshop participants focused on two particular instances in which ethical conflicts may arise: when a health professional must make a decision about returning to duty a soldier who has experienced a closed head injury, and when a professional must decide how to handle captured detainees who choose to engage in a hunger strike or other ethically charged activities.

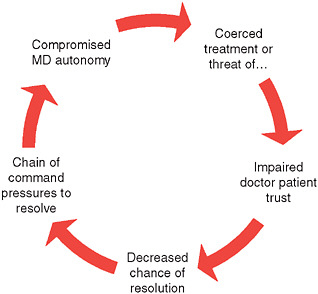

Military Medical Ethics: Issues Regarding Dual Loyalties: Workshop Summary (2008) identifies a number of areas of common ground, but also a number of areas in need of continued discussions. Participants discussed at length the need for transparency in policies and processes related to mili-

Potential for a spiral of impaired trust in prisons.

SOURCE: Military Medical Ethics: Issues Regarding Dual Loyalties: Workshop Summary, p. 20.

tary ethics, and on the need to seek a wide range of public and professional perspectives when dealing with such issues. They also discussed a need for improvements in training in medical ethics and outlined steps that public and private organizations might take in supporting better ethical awareness and expanded use of ethical standards.