5

Process for Developing the Meal Requirements

Meal Requirements encompasses standards for school meals that are used for two purposes: (1) to develop menus that are consistent with Dietary Guidelines and the Nutrient Targets and (2) to specify what qualifies as a meal that is eligible for federal financial reimbursement. Meal Requirements comprise standards for meals as offered by the school and standards for meals as selected1 by students. As offered meal standards are applied in the development of menus for school breakfast and lunch and thus may be called standards for menu planning. As selected meal standards are used by the cashier to determine whether the student has selected a meal that meets requirements for reimbursement. The process used by the committee to develop the Meal Requirements was iterative in nature, and it also contributed to the committee’s final recommendations for the Nutrient Targets. This chapter describes the processes used to develop recommendations for the Meal Requirements. Different processes were used to develop the standards for menu planning and for meals as selected. The final recommendations appear in Chapter 7.

DEVELOPMENT OF STANDARDS FOR MENU PLANNING

The development of standards for menu planning involved five major steps: (1) consideration of the adequacy of the meal planning approaches in current use; (2) the selection of the new meal planning approach; (3) the identification of an established food pattern guide to serve as a basis for

school meal patterns for planning menus that are consistent with Dietary Guidelines for Americans; (4) the design and use of spreadsheets to test possible meal patterns against the preliminary nutrition targets established in Chapter 4; and (5) the testing of a series of possible standards for menu planning and evaluation of the resulting menus in terms of nutrient content, cost, and suitability for school meals. These steps are described briefly below. Appendix H describes the third and fourth steps in more detail.

Consideration of Current Menu Planning Approaches

The two major categories of menu planning in current use are food-based menu planning and nutrient-based menu planning.

-

A food-based approach relies on the use of an approved meal pattern to serve as the basis for menu planning. The pattern specifies that the menu must include minimum amounts of food from selected food groups. The approach does not require the use of computer analysis to ensure that the existing Nutrient Standards are met, but some school food authorities (SFAs) supplement their food-based approach by conducting computerized analysis of some nutrients. Food-based approaches are the most common method of menu planning in current use (USDA/FNS, 2007a).

-

A nutrient-based approach focuses on nutrients rather than food groups. The menu planner uses a computerized process to ensure that the nutrient content of the menus conforms to the existing Nutrition Standards. The method does not include any food group specifications other than fluid milk. Two evaluations of nutrient-based menu planning (USDA/FNS, 1997, 1998a) revealed challenges related to staff resources, time requirements, and the software used but reported that the approach offered increased flexibility in menu planning. The resulting menus tended to be lower in saturated fat than they had been before the approach was adopted and tended to meet the existing Nutrition Standards for protein, two vitamins, and two minerals. Student participation rates and program costs remained about the same.

Development of a New Meal Planning Approach

A major component of the committee’s task was to make recommendations for menu planning that would improve the consistency of school meals with both the Dietary Guidelines and the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs). Although the nutrient-based approach has certain advantages, the committee identified two serious limitations of this menu planning approach:

-

Analysis of an expanded list of nutrients (the preliminary nutrient targets [see Table 4-5] rather than the current five nutrients) would be needed because there is little evidence of “key” nutrients that would ensure an overall nutritionally adequate diet. This larger set of nutrients would create practical problems for the nutrient-based approach because of limited food composition data for many foods used in school meals and because the necessary software is not available to the school food authorities.

-

A focus on nutrients alone does not ensure alignment with the Dietary Guidelines recommendations, which place a strong emphasis on foods; and it may, in some cases, lead to unnecessary reliance on specially fortified foods.

Using solely a food-based meal planning approach, the foods offered could be made more consistent with Dietary Guidelines recommendations, and the meal pattern could be designed to be reasonably consistent with the DRIs for protein, nine vitamins, six minerals, fiber, and linoleic and α-linolenic acids (as illustrated in Chapter 3). However, a food-based approach alone would not be sufficient because it would not ensure that menus are appropriate in calorie content and meet Dietary Guidelines recommendations for saturated fat and sodium. Therefore, the committee concluded that a combined meal planning approach—one that is food based but that also incorporates specifications for a small number of dietary components—was needed to improve consistency with both the Dietary Guidelines and the DRIs. Although the committee considered more complex approaches that required additional nutrient analyses, it determined that a well-specified menu pattern precluded the need for such analyses.

Identification of a Food Pattern to Guide School Meal Planning

In response to comments on the Phase I report (IOM, 2008), the committee considered two food pattern guides to serve as a basis for the school meal patterns: the Thrifty Food Plan (USDA/CNPP, 2007) and the MyPyramid food intake patterns (USDA, 2005). The Thrifty Food Plan was designed for planning a minimal cost, healthful diet. The first constraint in developing the plan was cost (USDA/CNPP, 2007). The plan incorporates consumption patterns of low-income families and is consistent with Dietary Guidelines. The committee decided against its use for two reasons. In particular, (1) the Thrifty Food Plan makes use of 7 major food groups but a total of 58 food categories—an unwieldy number for SFAs to use for menu planning purposes; and (2) several categories of food listed under the plan’s “other” group (ready-to-serve and condensed soups, dry soups, and frozen or refrigerated entrées [including pizza, fish sticks, and frozen meals]) are foods that are used frequently in many school meal programs. (The nutrient

profiles of the “other” foods used by school meal programs tend to be more favorable than those of similar foods included in the Thrifty Food Plan.)

As described in Chapter 3 and in more detail in the Phase I report (IOM, 2008), the MyPyramid food intake patterns provide a basis for planning menus for a day that are consistent with the Dietary Guidelines and that provide nutrients in amounts that equal or exceed the most current Recommended Dietary Allowances—with two exceptions (vitamin E and potassium). The MyPyramid patterns specify amounts of foods from six major food groups and seven food subgroups—a larger number of food groups than currently used for planning school meals2 but a number judged workable by the committee. To ensure that the nutrient amounts provided by the MyPyramid patterns would meet the School Meal-Target Median Intakes (School Meal-TMIs), the committee compared School Meal-TMIs for the elementary school, middle school, and high school age-grade groups with the nutrient content of MyPyramid patterns for 1,800, 2,000, and 2,400 calories (see Table 4-6 in Chapter 4). The School Meal-TMI values are less than 100 percent of the amounts of the nutrients in the MyPyramid patterns except for vitamin E and potassium for all age-grade levels, protein and calcium for schoolchildren ages 11 years and older, and also magnesium for schoolchildren ages 14 years and older.

MenuDevelopment Spreadsheets

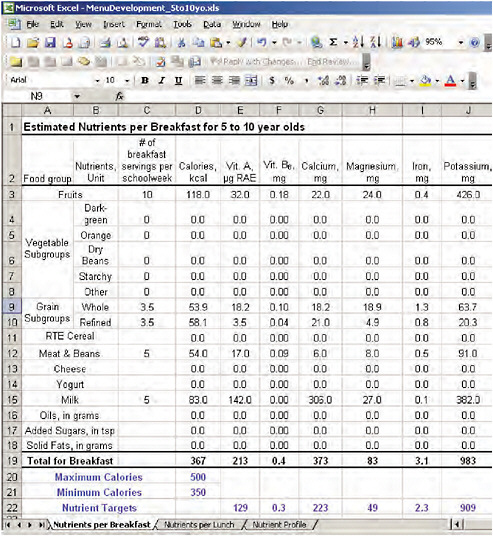

The committee developed spreadsheets (called MenuDevelopment spreadsheets) to assist in designing and evaluating preliminary meal patterns for school breakfast and lunch. Upon entering test values for a meal pattern (the number of servings3 from each food category per week), formulas in the spreadsheets calculate an estimate of the average daily nutrient content of the pattern and show how the nutrient estimates compare with the preliminary targets (preliminary nutrient targets are given in Table 4-7 in Chapter 4). These spreadsheets primarily used the 2005 MyPyramid nutrient composites (Marcoe et al., 2006) to estimate the energy and nutrient content that would be provided by possible meal patterns for breakfast and lunch. Modifications to the nutrient composites to make them more suitable for school meals are indicated in footnotes to Table H-2 in Appendix H. Figure 5-1 shows a portion of the spreadsheet for school lunch for ages 5–10 years (kindergarten through grade 5). The committee recognizes that the estimates obtained using the MenuDevelopment spreadsheets are

FIGURE 5-1 Excerpt from a late version of the MenuDevelopment spreadsheet for estimating and evaluating the average daily energy and nutrient content that would be provided by possible meal patterns for breakfast, using preliminary targets for schoolchildren ages 5–10 years (kindergarten through grade 5). The spreadsheet had been revised during the iteration period to include separate rows for low-fat cheese and low-fat sweetened yogurt (see Chapter 6). Added sugars and solid fats are included for testing purposes; they were not intended to be part of the menu pattern.

NOTES: The MenuDevelopment spreadsheet provides nutrient output for an additional 21 nutrients. Information about the food groups and nutrient composites used can be found in Appendix Table H-2. The “servings” refer to the amounts of food as specified in Appendix Table H-1. The use of unsaturated oils is encouraged within calorie limits.

approximations. The nutrient composites were designed using food consumption data from adults as well as children. Nonetheless, the committee considers them to be good approximations that help to design and test for nutritionally sound meal patterns.

School Meal Pattern Development

To begin developing the meal patterns, the committee assigned amounts of food from each MyPyramid food group to breakfast and lunch using the percentage of calories assigned for each meal. That is, for each age-grade group, the initial breakfast and lunch patterns (Table H-3 in Appendix H) were designed to correspond to approximately 21.5 percent of the MyPyramid amounts for breakfast and 32 percent of the MyPyramid amounts for lunch. This method keeps the food group amounts proportional to the number of calories specified for the meal. Because it is uncommon for a majority of U.S. schoolchildren to consume vegetables at breakfast (with a few exceptions, such as hash-brown potatoes), the committee agreed to omit all vegetables from the trial breakfast patterns and to test the effects of adding more fruit at breakfast.

The patterns were adjusted up or down if necessary to achieve practical serving amounts. For example, instead of specifying 0.8 cups of vegetable per day, ¾ cup or 1 cup would be specified. As work progressed, meal patterns were adjusted to consider student acceptance and school meal operations. (These topics are addressed further in Chapter 6.)

Because the foods specified by MyPyramid are the lowest fat forms and are free of added sugars, it was necessary to take discretionary calories (calories primarily from saturated fat and added sugars) into account during the testing with the MenuDevelopment spreadsheets. An allocation as made for the added sugars in flavored fat-free milk, for example, because retaining this type of milk in school meals is one way to promote milk intake by students (Garey et al., 1990). Although tentative allocations were made for discretionary calories from added sugars and saturated fat components, they were not intended to be part of any meal pattern.

Setting Additional Specifications

In working with the MenuDevelopment spreadsheets, it became obvious that three specifications from the preliminary nutrient targets would need to be an integral part of the standards for menu planning (that is, for meals as offered): (1) the minimum and maximum calorie level, (2) the limit on saturated fat, and (3) the maximum level of sodium. Simply specifying the number of servings to include from each of the food groups would not ensure that the meals would meet those targets. Evidence from the third

School Nutrition Dietary Assessment study (SNDA-III) makes it clear that calories, saturated fat, and sodium merit special attention. Thus the committee considered these additional dietary components when developing the standards for menu planning. The levels of total fat were consistently below 35 percent of calories when calories and saturated fat were controlled.

The committee notes that its approach to developing the standards for menu planning leaves relatively few discretionary calories for added sugars and saturated fat. In conjunction with the meal patterns, the specification of a maximum calorie level places limits on the use of foods with added sugars. This is quite consistent with the new recommendation from the American Heart Association (AHA) (Johnson et al., 2009) to limit added sugars to about half of the discretionary calorie allowance. With careful menu planning, enough discretionary calories should be available to cover flavored fat-free milk in place of plain fat-free milk as a daily option, some flavored low-fat yogurt, and some sweetened ready-to-eat cereals. These are highly nutritious foods that are very popular with many schoolchildren and that are identified in the AHA statement as potentially having a positive impact on diet quality. Fruits in light syrup contain about 10 grams of added sugars per half cup serving.4 The omission of those sweetened foods might result in decreased student participation as well as in reduced nutrient intakes.

Testing of Revisions of Standards for Menu Planning

To test revisions of the standards for menu planning, the committee used two methods:

-

revision of representative baseline menus to determine the types of changes needed to meet new standards, followed by analysis of modified baseline menus to allow comparison of the nutrients, key food groups, and cost before and after the revision; and

-

writing sample menus to meet the revised standards.

This section describes both of these methods. The iterative nature of the methods is addressed in Chapter 6.

Analysis was conducted using a software application called the School Meals Menu Analysis (SMMA) program (see Appendix K), which was designed for this project at Iowa State University. After the data were entered in the program, the application allowed the estimation of the average daily (1) content of energy and 23 nutrients and (2) food cost for each set of

5-day menus. The committee implemented quality control procedures to verify acceptable performance of the application, to ensure that the revised baseline and sample menus met the revised meal standards, and to verify that the menus had been entered into the software application accurately.

Test Menus and Representative Baseline Menus

The committee initially wrote menus to test the practicality of possible revisions of the meal standards. To support analysis of effects of the revisions on nutrients and the possible effects of the revisions on cost, the committee identified a group of menus (called representative baseline menus) that provide a representation of meals currently served in the School Breakfast Program and the National School Lunch Program (NSLP).

Selection of Representative Baseline Menus SNDA-III, which includes data on the meals offered and served in a nationally representative sample of 397 schools, was the source of the menus. The committee identified menus for breakfast and lunch for each of three different school levels (elementary, middle, and high) and included equal numbers of menus planned using food-based and nutrient-based menu planning approaches. As a result of its decision to use primarily a food-based approach to menu planning, the committee identified and used a subset of six different representative baseline menu sets, each of which covered five school days. Although schools have two options for food-based menu planning (traditional or enhanced), the committee focused on traditional food-based menu planning because it is the most widely used system. About 48 percent of all schools use a traditional food-based approach, 22 percent use an enhanced food-based approach, and 30 percent use a nutrient-based approach to menu planning (USDA/FNS, 2007a). In addition, the traditional food-based menu plan requires less food than the enhanced food-based plan and thus provides a better baseline for assessing the impacts of proposed revisions on nutrient content and costs. The procedures for selecting the baseline menus appear in Appendix L.

Use of Representative Baseline and Modified Baseline Menus The committee modified the representative baseline menus as described in Chapter 6 and reviewed the results. Changes in alignment with the Dietary Guidelines were determined by inspection of the menus. Both the representative baseline menus and the modified baseline menus were then analyzed using the aforementioned SMMA software application. Factors considered in the analyses included changes in the nutrient content, consistency with the initial nutrient targets, and the mean cost relative to the mean cost of the representative baseline menus.

Sample Menus

Once the recommendations for the standards were finalized (see recommendations in Chapter 7), the committee wrote sample menus based on those standards, entered them in the SMMA program as described in Appendix K, and analyzed the results as described above. The sample menus appear in Appendix M, and the results of the analyses appear in Chapter 9.

DEVELOPMENT OF STANDARDS FOR MEALS AS SELECTED BY STUDENTS

Background

Prior to 1975, regulations for Meal Requirements were based only on meals as offered. At the time, a food-based menu pattern (primarily the Type A pattern mentioned in the excerpt that follows) was used as the sole approach to menu planning, and participants were required to take all five of the food components offered at lunch. In October 1975, Congress passed P.L. 94-105 (see Box 5-1), which included language targeted toward reducing food waste in the NSLP. That law led to the establishment of rules governing the number of food components that must be included in a reimbursable meal as served. The excerpt below summarizes the initial regulations.

In order to ensure that children are provided as [sic] nutritious and well-balanced lunch, and have the opportunity to become familiar with, and enjoy different foods, present regulations require that they be served the complete lunch. In some instances this requirement has resulted in plate waste. In furtherance of the objective of reducing food waste, Pub. L. 94–105 requires that students in senior high schools participating in the National School Lunch Program not be required to accept offered foods which they do not intend to consume. The regulations have been amended so that students in senior high schools, as defined by the State and local educational agency, shall be offered all the five food items comprising the full Type A lunch and must choose at least three of these food items in order for that lunch to be eligible for Federal reimbursement. Further, the intent of Congress is reflected in the regulations to: (1) Require that if a student chooses less then [sic] the complete Type A lunch, the student would be expected to pay the established price of the lunch; (2) the amount of reimbursement made to any such school for such a lunch will not be affected.

Federal Register, Vol. 41, No. 21—January 30, 1976, Proposed Rulemaking

|

BOX 5-1 Excerpts from Laws Relating to Offer versus Serve P.L. 94-105 (October 7, 1975) Sec. 6. Section 9 of the National School Lunch Act is amended as follows: “(a) Subsection (a) is amended by adding at the end thereof the following new sentences: The Secretary shall establish, in cooperation with State educational agencies, administrative procedures, which shall include local educational agency and student participation, designed to diminish waste of foods which are served by schools participating in the school lunch program under this Act without endangering the nutritional integrity of the lunches served by such schools. Students in senior high schools which participate in the school lunch program under this Act shall not be required to accept offered foods which they do not intend to consume, and any such failure to accept offered foods shall not affect the full charge to the student for a lunch meeting the requirements of this subsection or the amount of payments made under this Act to any such school for such a lunch.” P.L. 95-166 (November 10, 1977) ACCEPTANCE OF OFFERED FOODS Sec. 8. The third sentence of section 9(a) of the National School Lunch Act is amended [by inserting the following phrase] (and, when approved by the local school district or nonprofit private schools, students in any other grade level in any junior high school or middle school). P.L. 97-35 (August 13, 1981) TITLE VIII—SCHOOL LUNCH AND CHILD NUTRITION PROGRAMS (95 Stat. 529) FOOD NOT INTENDED TO BE CONSUMED Sec. 811. The third sentence of section 9(a) of the National School Lunch Act is amended by striking out “in any junior high school or middle school.” Revised Language of the Current Law (also cited in P.L. 95-166): Students in senior high schools that participate in the school lunch program under this Act (and, when approved by the local school district or nonprofit private schools, students in any other grade level) shall not be required to accept offered foods they do not intend to consume, and any such failure to accept offered foods shall not affect the full charge to the student for a lunch meeting the requirements of this subsection or the amount of payments made under this Act to any such school for such lunch. P.L. 99-591 (October 30, 1986) Sec. 331. Section 4(e) of the Child Nutrition Act of 1966 is amended by addition at the end thereof the following new paragraph: “(2) At the option of a local school food authority that participated in the school breakfast program under this Act may be allowed to refuse not more than one item of a breakfast that the student does not intend to consume. A refusal of an offered food item shall not affect the full charge to the student for a breakfast meeting the requirements of this section or the amount of payments made under this Act to a school for the breakfast.” |

The committee considered the relevant wording of P.L. 94-105, the excerpt of the proposed rule above, and subsequent amendments to the law (Box 5-1). Current usage refers to the offer versus serve (OVS) provision. OVS is mandatory for senior high schools, became optional for middle schools in 1977, and, in 1981, became optional for elementary schools as well as middle schools. The option has been adopted widely: in school year 2004–2005, SNDA-III found that 78 percent of elementary schools and 93 percent of middle schools used OVS (USDA/FNS, 2007a).

P.L. 94-105 makes it clear that the administrative procedures developed to implement the law are

-

to be established by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (the Secretary) with substantial input from state educational agencies and also with the participation of local educational agencies and students,

-

to reduce waste of foods served in the NSLP, and

-

to maintain the “nutritional integrity” of the meals served.

The current rules (typically called the as served meal standards) provide limits on the number (and sometimes the type) of food components that may be declined, as shown in Tables 1-1 and 1-2 in Chapter 1. These existing meal standards clearly provide a mechanism for reducing food waste. The term as served has been a source of confusion, however, because under OVS the food that the student is served is the food that the student selects. For this reason, the committee uses the term standards for meals as selected to apply to the standards for OVS. The terms meals as served or simply meals served apply to the food placed on the student’s tray regardless of whether OVS is in effect.

Review of Published Evidence

A few published studies provide data relevant to setting standards for meals as selected. Using a visual estimation method of measuring food consumption by 457 elementary school students in Louisiana, Robichaux and Adams (1985) concluded that OVS and the traditional method of serving were generally comparable in terms of food consumption by participating students. In a study evaluating OVS at a middle-income elementary school (N = 201) and a high-poverty elementary school in Alabama (N = 170), Dillon and Lane (1989) reported the percentages of students selecting the various food components on each day of a 5-day school week. Selection of the entrée and milk approached or equaled 100 percent. Selection of a fruit serving approached 100 percent on three of the days, especially in the high-poverty school, but on one day it went as low as 44 percent in the middle-income school. The selection of grains also was high, either as part

of an entrée or as an accompaniment to an entrée. In contrast, much smaller percentages of the children selected vegetables (10 to 34 percent of the children in the middle-income school and 33 to 68 percent of the children in the high-poverty school).

Analysis of data from the first School Nutrition Dietary Assessment study (SNDA-I) (USDA/FNS, 1993) revealed that NSLP participants wasted about 12 percent of the food energy and from 10 to 15 percent of the individual nutrients that they were served. The overall nutrient intakes of the students did not differ when OVS and non-OVS schools were compared. Compared with findings at non-OVS schools, smaller percentages of students of similar age were served milk at OVS schools, but they wasted less food. High school males wasted the least food (about 5 percent) and 11–14-year-old female participants wasted the most (about 17 percent).

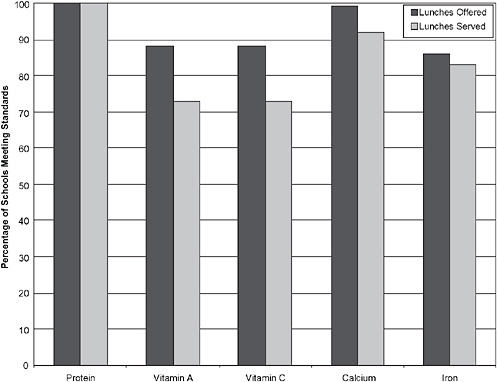

Data from SNDA-III show that only half of the schools served lunches that met the existing energy standard, whereas 71 percent of the schools offered lunches that met the standard. Clearly, students did not select all the offered food components. Figure 5-2 allows comparison of the percentages of schools meeting existing (School Meal Initiative) standards for key nutrients as offered by the schools and as served to the students. These percentages represent averages for the schools. If a student declines food items, the nutrient content of that student’s meal may be reduced substantially more than is illustrated in Figure 5-2. For example, a student who declines milk and a vegetable will have a meal that is reduced in calories, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, zinc, vitamins A and D, B vitamins, and other nutrients.

In summary, data indicate that the use of the OVS provision has led to less waste (and therefore reduced food cost) and the selection of fewer food components by some students (therefore reduced calories and nutrients on the tray). Notably, in a multivariate analysis, predicted participation rates were significantly higher in elementary and middle schools that used OVS at lunch than in those that did not (70 percent, compared with 44 percent) (USDA/FNS, 2007a). Higher student participation rates translate to more students benefiting from school meals and more revenue for the program.

Methods

Because the standards for meals as selected by students apply to a large majority of elementary and middle schools as well as to all senior high schools, the committee recognized that recommendations for these standards would have a large impact on students’ food selections and on the nutrient content of their meals. To provide a sound nutritional basis for the standards, the committee analyzed nutrient data related to several options for the standards at both breakfast and lunch. Then it compared

FIGURE 5-2 Percentages of schools meeting existing (School Meals Initiative) standards for key nutrients as offered by the schools and as served to the students in National School Lunch Program lunches.

SOURCE: USDA/FNS, 2007a.

estimates of the nutrient content of those options with the Nutrient Targets for the meal.

In particular, the MenuDevelopment spreadsheets were used to examine how various omissions may affect the nutrient content of school meals. The spreadsheets made it possible to estimate the effects of omitting specific types and amounts of food from the breakfast and lunch patterns for the three age-grade groups. This process provides nutrition information relevant to the specificity of the standards for meals as selected and to the minimum number of food items that would be allowed. The omissions that were tested appear in Box 5-2. These food items were chosen based on evidence regarding food items commonly declined by students.

Results

Tables presenting the results of the analyses appear in Appendix H (Tables H-4 through H-7). The analyses provide data on the effect of specific omissions on the approximate nutrient content of the meal (breakfast

or lunch) and relate the nutrient content to the preliminary nutrient targets for the meal. The committee specifically considered nutrient shortfalls. In these summaries, the term shortfall applies to nutrient contents that are less than 80 percent of the Nutrient Target for the meal. As anticipated, the vitamin E content of the meals is well below the nutrient target even before testing the omission of any foods.

For breakfast, the omission of all fruit at breakfast leads to shortfalls in dietary fiber, vitamins C and B6, magnesium, and potassium. The omission of milk at breakfast leads to different shortfalls relative to the nutrient targets for the three age-grade groups, but the vitamin D content would be very low for all. The nutrients of concern may include vitamin A, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and potassium, depending on the age-grade group.

The committee noted that for lunch the omission of two vegetables (that is, the case where no vegetables were selected by the student) causes the meal’s content of fiber and potassium to be well under 80 percent of the Nutrient Target for all grades; magnesium would be a shortfall nutrient for high school students. Omitting milk leads to nutrient content that is well under 80 percent of the target for calcium and phosphorus, and also to shortfalls in potassium and/or riboflavin, depending on the age-grade group. In addition, the vitamin D content of the meal would be very low.

SUMMARY

This chapter describes the processes used to develop the Meal Requirements—standards for meals as offered by the school and as selected by the student. The committee used several types of analysis to inform decisions related to meal patterns and additional specifications for standards for menu planning (the as offered meal standards). It also used analytic methods to address the question of what and how many food items might be required for a meal to qualify for federal reimbursement under OVS (the standards for meals as selected by students). Chapter 6 covers some aspects of the iterative nature of the process and major challenges to the development of the Meal Requirements. Recommendations for the Meal Requirements appear in Chapter 7.