Reimbursement

In addition to technological and regulatory hurdles to the development of personalized medicine in oncology, reimbursement hurdles also exist. Drs. Jeff Roche and Amy Bassano of CMS described how Medicare decides what predictive tests to reimburse and how much to reimburse for a test. Their presentations were followed by critiques of the current reimbursement system, as well as suggestions for improving the reimbursement of predictive tests.

MEDICARE COVERAGE OF PREDICTIVE TESTS

Dr. Roche explained that the Social Security Act of 1965 established Medicare, a health insurance program run by the U.S. government for individuals age 65 and over, or for individuals who meet special criteria.1 Medicare pays for services and items that are reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury in those who qualify for the program.2 In general, Medicare is not required to cover screening services, although there are certain exceptions (e.g., Medicare covers the cost of Pap tests, colorectal cancer screening tests, mammograms, and the PSA screening test). The diagnostic services that Medicare covers are done in a variety

of settings, Dr. Bassano noted, including hospitals, physician offices, and independent labs.

For a medical intervention to qualify as reasonable and necessary, evidence must show, among other considerations, that the item or service improves clinically meaningful health outcomes in Medicare beneficiaries (CMS, 2009c). Evidence is assessed using standard principles of evidence-based medicine. CMS generally follows the evaluation process developed by other agencies or advisory bodies, such as AHRQ, USPSTF, and EGAPP. Genetic test coverage determinations are particularly challenging because genetic tests can be used for both diagnostic and screening purposes, Dr. Roche said. In addition, the evidence base is small for genetic tests, and the science is evolving. “The ultimate health outcomes attributable to genomic testing are not clear at this time,” Dr. Roche said, and there can be dangers in making some coverage determinations prematurely.

More recently, CMS has begun using criteria for Analytic validity; Clinical validity; Clinical utility; and Ethical, legal, and social implications (ACCE) (CDC, 2009) in making decisions on whether sufficient evidence exists to justify coverage of predictive tests. However, CMS has not yet formally adopted the ACCE framework or any other framework of evidence for predictive testing. In general, CMS rates evidence according to health outcomes. Diagnostic tests that lead to longer life expectancy, improved function, or significant symptom improvement are rated higher than tests that result in doctor confidence or earlier detection without improved survival (Box 1).

Some Medicare coverage decisions are made at the national level of the organization, but approximately 85 to 90 percent of coverage decisions are made by local contractors (CMS, 2009b). Local contractors can increase national coverage and reimburse additional procedures. For example, some local contractors cover gene marker tests for hereditary cancer syndromes, including ovarian cancer and colorectal cancer, assuming certain conditions are met (i.e., the individual is clinically affected by the disorder and is willing to undergo pretest genetic counseling). While some contractors do not cover these gene marker tests, local coverage of genetic analyses must be provided through a laboratory that meets ASCO’s recommended requirements, and the patient must sign an informed consent form prior to testing.

Dr. Ratain pointed out that because laboratories can receive samples for testing from all over the country, some local coverage decisions have national ramifications. For example, a California Medicare contractor made

|

BOX 1 Rating Evidence of Health Outcomes More Impressive

Less Impressive

SOURCE: CMS presentation (June 9, 2009). |

a decision in 2007 to cover chemotherapy sensitivity testing, and laboratories that provide this testing in southern California can receive samples from anywhere in the United States. Dr. Ratain believes there is inherent unfairness in a system that enables a laboratory in one area of the country where the predictive test is covered to do nationwide testing, yet deny reimbursement for such testing to a laboratory located in other areas with different local coverage determinations. Dr. Roche acknowledged the inconsistency in policy, but pointed out that “when you lose local coverage discretion, you’re also losing the ability of a local coverage organization to respond to the needs that are being expressed in that region of the country.”

Dr. Roche also stated that CMS often consults with experts in other government agencies, such as those at the FDA and CDC, as well as with professional societies such as ASCO, the American Society for Hematology, and the American College of Chest Physicians, when making coverage decisions. “We are now realizing that things that are embedded outside of CMS deserve more than a second look, and we’re trying to integrate this information and understand better some of the implications [of coverage decisions] on the system,” he said.

REIMBURSEMENT RATES

Dr. Bassano explained how Medicare determines the payment rate for diagnostic tests. The Medicare payment rate for diagnostics is calculated as the lesser of

-

the amount billed;

-

the local fee for the area; or

-

the national limitation amount (NLA) for the particular code.

The NLAs are on a fixed-fee schedule. For tests that had NLAs established before January 1, 2001, the NLA is 74 percent of the median of all local fee schedule amounts. NLAs established on or after January 1, 2001, are 100 percent of the median. Fees may be updated by statute, but are not updated regularly. No updates occurred between 2004 and 2008. In 2009, fee rates were increased by 4.5 percent. “This is an older system that hasn’t had the same type of updating or scrutiny by Congress that some of the other physician or hospital systems have. It’s not resource based, nor is it a prospective payment system, and there’s really no opportunity for CMS to reassess the payment rates for the codes,” said Dr. Bassano. Furthermore, there are no budget neutrality requirements for Medicare reimbursement of diagnostics.

Dr. Quinn asserted that the fixed-fee schedule for diagnostics hampers innovation. For example, fee rates are currently around $14 for all PSA tests, he said. This test frequently has been criticized by clinicians for insufficient specificity. If an improved version of the test was developed, this would require substantial resources. However, the new test would receive reimbursement at the same rate as the older, less effective PSA test because of the lack of specificity in the fee schedule.

There is a process, however, for annually updating the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for new diagnostics. (The CPT code categorizes the diagnostic and ultimately determines its fee rate.) To determine the CPT code for new tests, the code can be crosswalked to an existing test, pricing the new test at the same rate as a similar test that already has a CPT code, or “gap filled.” Gap filling requires Medicare contractors to collect data specific to their geographic area and to set a new price that reflects those data. This process is burdensome, so most new code pricing is determined by crosswalking. CMS collects public feedback on the new code pricing before putting it into practice.

Dr. Bassano noted that many laboratory-developed tests come from

independent labs that are not required to have a CPT code. Instead they are given an unlisted code that the lab can use to bill, and that price is set by the local contractor. These tests tend to be more expensive, costing as much as thousands of dollars. Also, this coding process is not tracked as well as that for tests using standard CPT codes, Dr. Bassano pointed out.

Alternatively, laboratory-developed tests can use a “stack” of generic chemical-test steps represented by CPT codes such as “83898 DNA Amplification” (AMA, 2009). These stacked CPT codes are often difficult to track, Dr. Quinn said. “You get a list of 30 CPT codes, and have no idea what the test is, what was done, what the accuracy is, what the characteristics are, and what the utility is.” Stacked codes can also provide disincentives to develop step-saving innovations, Dr. Shak added, because the current system of CPT codes pays for activity, not value. For example, an older test to detect methylation known as the Southern methylation analysis requires six steps, whereas a newer PCR methylation test requires only four of those steps (Table 2). Consequently, the older test is reimbursed at a higher rate, despite the fact that the newer test has improved dependability and performance, eliminates the need for radioactivity, and produces faster results. Laboratories that choose to do the better PCR-based methylation test are paid less than those that

TABLE 2 Current System of CPT Codes Pays for Activity, Not Value

continue to use the older test. “The rewarding of activity perversely can lead to the performance of lots of unnecessary steps,” Dr. Shak said.

Several presenters and speakers said another major problem with the reimbursement rates for predictive tests is that they are far lower than therapeutics. For example, the Oncotype DX test, which identifies node-negative, ER-positive breast cancer patients for whom chemotherapy is unlikely to help, costs $3,500 a test, Dr. Hayes said. Yet he estimates that the test provides a net healthcare savings of about $1 billion annually by preventing the ineffective use of chemotherapy. Most health insurers balk at the prospect of paying $3,500 for a test, but “that’s cheap if it’s going to save $50,000 in chemotherapy expenses,” he said. Dr. Quinn added, “Cost-saving innovations are potentially huge. We just need a pathway to make it possible.”

Additionally, the high complexity of the technology used in many predictive tests, such as gene splicing, should drive up the cost of the tests, Dr. Quinn stressed. “Every test is almost like a master’s degree back when I was in college.” He estimated that developing a new test can cost more than $50 million, but may only be used by 10,000 patients a year. Breaking even on development costs in 5 years would require recouping about $10 million, which boils down to a fee of a few thousand dollars per test. This level of reimbursement would not result in a profit or cover operating costs and other company expenses linked to the test, Dr. Quinn noted. Ms. Stack concurred, noting that “It’s expensive to do quality development and we need to be able to charge a fair market value [for our tests], like we do for drugs. It’s not too much to ask to charge 10 to 20 percent of what a therapy would cost for a diagnostic that’s innovative.”

BUNDLING OF PAYMENTS

Dr. Bassano stated that Medicare prefers to have one payment for all the services provided to a patient during a hospital stay. This often means that the reimbursement for a test done on a specimen collected during a hospital stay is bundled with a reimbursement payment for other hospital services. The bundled payment is made to the hospital, not to the laboratory doing the testing. Since 2001, Medicare rules state that the date of service for reimbursed laboratory services is generally the date the specimen is collected (CMS, 2009a). If a specimen is stored less than 30 days, payment for the test performed on that specimen is bundled into the payment for the inpatient hospital stay, and there is no separate payment for the test,

Dr. Bassano explained (CMS, 2009a). An outpatient center can also bill for the test. For tests done on specimens stored for more than 30 days, the date of service is the date the specimen was removed from storage, and payment is separate from inpatient payments (CMS, 2009a). In this case, the lab doing the test does the billing, rather than a hospital.

In response to complaints by stakeholders, this rule was modified in 2007 to allow some payments for tests to be unbundled from the payment for hospital service. This exception applies if the test was performed on a specimen collected during a hospital stay and stored for less than or equal to 30 days, and one of the following conditions applies:

-

The test was ordered at least 14 days following the date of the patient’s discharge from the hospital.

-

The specimen was collected while the patient was undergoing a hospital surgical procedure.

-

It would be medically inappropriate to have collected the sample other than during the hospital procedure for which the patient was admitted.

-

The results of the test do not guide treatment provided during the hospital stay.

-

The test was reasonable and medically necessary for treatment of an illness.

These exceptions are viewed as insufficient by some stakeholders, Dr. Bassano noted. She said industry claims the inpatient bundling of payments was not intended to cover the costs of expensive, complex tests, and that such bundling inhibits the development of tests performed in a single location. Laboratories do not want to negotiate the reimbursement rates for their tests with hospitals located throughout the country, and would rather negotiate directly with local Medicare contractors, Dr. Bassano said.

Dr. Quinn concurred, saying, “This means that the lab has to contract with 5,000 hospitals, instead of one Medicare program or contractor. So the transaction costs go through the roof.” Hospitals also do not want to take on the audit risk, he added; there is an auditing requirement that hospitals track down all the hospital and doctor records involved in the testing done on an oncology specimen acquired at the hospital. Often, specimens are transported to multiple physicians or cancer facilities throughout the country, so this is a major undertaking. In addition, by bundling tests into hospital payments, CMS loses the opportunity to recoup payment if its

audit of a lab determines the service was not medically necessary. “Once the test is being done all across the country, in 3,000 hospitals, and with an unlisted code, it’s no longer auditable,” Dr. Quinn said.

Ms. Stack observed that “a lot of our companies are testing samples that were collected in a hospital, and they don’t want to wait 15 days to do the genomic tests so that they can be in accordance with the 14-day rule,” she said. Another problem with the rule is that it creates a bias against inpatient cancer care because such care requires bundling of the test reimbursement into the total hospital payment, rather than reimbursing the lab directly, Dr. Quinn said. “If you have something like a brain tumor that requires inpatient surgery, you’d be biased against developing a test for it, but if it’s a lumpectomy with a lot of outpatient surgery, you’d be more biased to develop a test for it. Large companies are very aware of that,” he said.

Dr. Quinn also questioned the logic of how Medicare bundles its payments, and called for more economically rational bundling. “If you bundled the cost of a $2,000 lab test backward to an $80 office visit or a $4 blood draw, it’s very hard to make economic sense out of that. If you would bundle that cost forward to the $50,000 chemotherapy, people would be knocking over themselves to use that test. So I think forward bundling could make a lot of sense if it was tied to chemotherapy. There are old rules that don’t apply now, and have really detrimental effects on the development of this [genetic testing] industry,” he said

VALUE OF BIOMARKERS

Dr. Hayes called for valuing markers as much as we value therapeutics. This will “require a wholesale change of the system,” he said. “A bad tumor marker is as harmful as a bad drug,” yet the evidence of safety and effectiveness required to put a tumor marker on the market is far lower than that for a tumor therapeutic. “We would not let drugs into the market based on Phase I data,” he said. “We insist on showing efficacy and safety before we allow people to use the drug, and we don’t just say, ‘well let’s get it out there and see if people like it’ because I think we convince or trick ourselves into thinking we like something when, in fact, it may not be helpful.”

The lack of evidence on tumor markers is appalling, Dr. Hayes stressed. Over the past 14 years, the ASCO Tumor Marker Guidelines Panel has only recommended the use of four tumor markers, despite publications on hundreds of such putative markers. The other markers the panel reviewed lacked sufficient evidence. Most tumor marker studies are tested in retro-

spective trials with multivariate or univariate analyses, he said, and have small sample sizes. Markers are not often tested in sufficiently powered studies or meta-analysis studies in which the marker was the primary objective of prospective testing, or in prospective studies in which the marker was the secondary objective (Hayes et al., 1996).

Despite their insufficiencies, the results of many tumor marker studies are published in reputable scientific journals, Dr. Hayes said. However, it takes years for this type of study to gather enough evidence on clinical utility. “We could truncate this entire process considerably by looking at markers the way we look at drugs,” he said. The clinical utility of a tumor marker can be shown through just one well-designed trial, he said, but using archived samples with many built-in biases could take two or three trials. “This makes it harder up front, but in the long run you actually get answers quicker that way,” Dr. Hayes said.

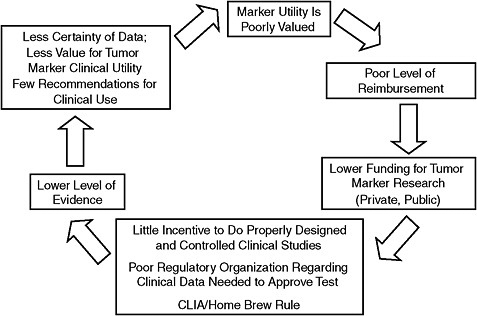

Unfortunately, doing large, controlled, prospective clinical trials of tumor markers would be much more costly, and untenable given the current reimbursement rates for predictive tests, Dr. Hayes said. “If we increase the rigor required to introduce a new predictive tests to that required to introduce a new drug, current reimbursement systems will smother innovation,” he said. Consequently, a vicious cycle is created: Because predictive tests are insufficiently reimbursed, shortcuts are taken in their development to save money, and their clinical safety and effectiveness is not adequately determined. As a result of their questionable utility, insurers continue to undervalue them and thus provide inadequate reimbursement (Figure 8). Given the low rates at which tests are reimbursed, and the inconsistent and often minimal amount of regulatory oversight on tests, “there is little incentive to do properly designed and controlled clinical trials,” Dr. Hayes said. “Therefore, there is a much lower level of evidence for markers than there is for drugs, less certainty of data, and less value for tumor marker clinical utility because people don’t know how to use them.”

In addition, the NIH, academic institutions, and other sponsors of clinical research do not value biomarkers as much as they do drugs, and consequently do not provide adequate support for clinical trials of these markers, Dr. Hayes said. This adds to the vicious cycle. “Tumor marker research is not perceived to be as exciting or as important as new therapeutics, especially the clinical component. There is less academic credit and funding for those of us who do tumor marker work.” Dr. Leonard concurred, saying, “The only thing we have to work with are convenient samples because there is no funding. That’s an NIH decision. So we have

FIGURE 8 Undervalue of tumor markers: A vicious cycle.

NOTE: CLIA = Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments.

SOURCE: Hayes Presentation (June 9, 2009).

to [work] with in vitro diagnostic companies that don’t pay, and that’s not respected in academia. It’s a terrible system and we have to fix it.”

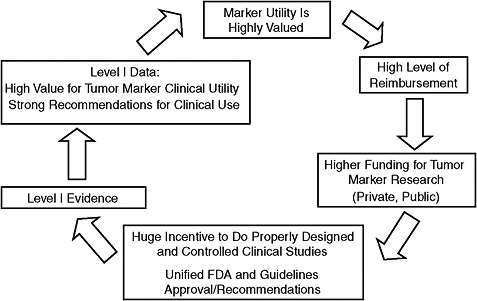

Dr. Hayes proposed what he called a “virtuous cycle” to replace the current vicious cycle (Figure 9). In the virtuous cycle, tumor markers would be highly valued, and thus researchers would receive greater funding for clinical trials to assess them. This would result in better evidence of their utility and require higher levels of reimbursement. The end result would be strong recommendations for clinical use of tumor markers that would occur much sooner, with proven efficacy. The study section the NCI recently started for cancer biomarker research is a first step toward implementing the virtuous cycle, Dr. Hayes noted. Previously, grants for clinical research on tumor markers were inappropriately reviewed by the pathology or therapeutic study sections. Another positive step is the fact that criteria for reporting tumor marker studies have been recently developed and adopted by scientific journals (Bossuyt et al., 2004; McShane et al., 2005).

To achieve the virtuous cycle, Dr. Hayes called on the patient advocacy community to promote the value of tumor markers, and to insist that CMS provide a higher level of reimbursement for predictive tests, commensurate

FIGURE 9 Highly valued tumor markers: Virtuous cycle.

NOTE: FDA = Food and Drug Administration.

SOURCE: Hayes Presentation (June 9, 2009).

with what is provided for drugs and with a more rigorous approval process for tests. Dr. Phillips added that private payers are key drivers in the reimbursement system and need to change their reimbursement rates for predictive tests.

In addition, Dr. Hayes suggested changing the method of caregiver reimbursement so that doctors can spend more time with their patients explaining predictive tests, and not be financially penalized for not recommending chemotherapy because the test indicates it will not be effective. “I can spend 15 minutes with a patient and say she should get chemotherapy, and she’ll probably be quite happy because it sounds like I’m being aggressive and doing the right thing, or I can spend 45 minutes to an hour explaining what the 21-gene recurrence score is, and why that patient probably won’t benefit from chemotherapy. If I do the latter, I think I’ll get $220 for the visit. If I do the former, my institution and I get about several thousand dollars. That’s not right. It should be the same, and I think we need to figure out how to make it the same,” Dr. Hayes said.

“Paying for outcomes will [also] drive the development of markers, and

until we pay for outcomes, the likelihood that there’s going to be money to develop a predictive test is going to be small,” said Dr. Friend. Dr. Parkinson added, “Maybe low levels of evidence will get low levels of reimbursement, and high levels of evidence and clinical utility will get higher levels of reimbursement. So all of a sudden, the system will be motivated to perform. We ’re starting to see pay-for-performance on the therapeutics development side. Maybe it’s time to have that on the diagnostics development side.” Dr. Ratain said it might be worthwhile to “create a completely level playing field where all medical technologies are reimbursed as something that is somehow tied to value.” Basing reimbursement rates for therapeutics on the value they provide might lower the cost of drugs and provide funds for increasing the price of predictive tests.

Several participants called for early reimbursement of predictive tests. Dr. McCormick of Veridex noted that small device companies such as his own operate differently from drug companies because they have less financial assets to do extensive clinical trials. Early reimbursement helps a device manufacturer to fund these trials. Dr. Herbst also urged early reimbursement in clinical trials of tests that assess multiple tumor markers “so you can [assess] the mutations you’re interested in and then look at others.” Both Drs. Johnson and Small noted that it can be problematic to run clinical trials of predictive tests because it is questionable whether health insurers will reimburse the cost of the tests.

Dr. Friend suggested developing an accelerated approval process for the codevelopment of a diagnostic and therapeutic. Alternatively, a predictive test could reach the market quickly for a new indication through off-label use. However, Dr. Quinn noted that off-label use of a diagnostic by the company that makes the test creates a conflict of interest, which is different from that seen in off-label use of drugs or devices. “We have this conflict that is more direct for innovative lab tests because the same company that produces the test—does the innovation—is also selling it, and that doesn’t occur anywhere else. GE makes positron emission tomography (PET) scanners and spends a billion dollars developing a new PET scanner. But then it sells them, and a hospital and a doctor will get the profit or manage the use,” he said. To recoup their innovation costs, companies that make laboratory-developed tests will be inclined to overpromote and overuse their tests.

Dr. Quinn also criticized relying on evidence-based medicine to determine use and reimbursement of tests. “Say I have colon cancer with a 10 percent chance of recurrence, and I have a PET scan that shows golf ball–sized lesions all over my innards. This test has an odds ratio of 3,

which means I have a 30 percent chance of having recurrent colon cancer. It doesn’t make any sense in the context of the diagnostic test,” he said, adding, “We have no good standard for coverage decisions. We say, ‘you need more evidence,’ but there’s no unit of evidence. You don’t measure evidence in cubic feet or in meters. We say ‘you need more evidence,’ but against what standard? There’s absolutely none.” He stressed that predictive tests are conceptually quite different from therapeutics, and should be evaluated differently.