Key Elements of America’s Climate Choices

A comprehensive and effective response to climate change requires a diverse portfolio of actions that evolve with new information and understanding.

As discussed in Chapter 4, a balanced risk management strategy for addressing climate change requires an integrated portfolio of policy options, including actions aimed at reducing the likelihood of adverse outcomes and actions aimed at reducing the damages such outcomes could cause. It further requires making investments over time to advance the knowledge on which future decisions will be based, to expand the options available to decision makers in the future, and to ensure that decision makers at all levels (including the public) have the information necessary to make decisions that properly reflect new knowledge and new options. Cutting across all of these elements are needs for international engagement and for coordinating the different actors and elements of an overall response strategy. This chapter offers recommendations along each of these dimensions, with an emphasis on near-term responses that enhance the capacity for, and reduce the costs of, more substantial responses that may be chosen in the more distant future.

LIMITING THE MAGNITUDE OF CLIMATE CHANGE

Limiting the magnitude of climate change requires stabilizing atmospheric greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations, which in turn requires reducing emissions of these gases so that their emissions are no greater than the rate at which they are naturally removed from the atmosphere. The basic opportunities available for reducing GHG emissions include restricting or modifying activities that release GHGs (e.g., burning of fossil fuels), removing CO2 from the waste stream of large point sources of emissions and sequestering it underground (carbon capture and storage), or augmenting natural processes that remove GHGs from the atmosphere, for example by managing agricultural soils or forests to increase the rate at which they sequester carbon (postemission GHG management). In addition, GHG emissions could potentially be offset by enhancing the reflection of solar radiation back to space (solar radiation management),

which together with some post-emission GHG management strategies is sometimes referred to as geoengineering (see Box 5.1). NRC, Advancing the Science and Limiting the Magnitude review the technologies and practices that are available for pursuing these various opportunities. Here we provide a very brief overview, starting with the more general issue of setting goals for limiting the magnitude of climate change.

BOX 5.1

Geoengineering

Geoengineering, applied to climate change, refers to deliberate, large-scale manipulations of the Earth’s environment intended to offset some of the harmful consequences of GHG emissions, and it encompasses two very different types of strategies: solar radiation management and post-emission GHG management.a Many proposed geoengineering approaches are ambitious concepts with global environmental consequences; as such, they have attracted a great deal of attention. In general, however, current scientific knowledge of the efficacy and overall risk reduction potential of most geoengineering approaches is limited.

Solar radiation management (SRM) involves increasing the reflection of incoming solar radiation back into space. Some SRM approaches can, in theory at least, produce substantial cooling quickly and thus could potentially be used in the case of “climate emergencies” involving unexpectedly rapid warming or severe impacts. A much-discussed example is the proposal to continuously inject large quantities of small reflective particles (aerosols) into the stratosphere.This would mimic some effects of sustained large volcanic eruptions, which have been observed to cool the earth’s surface measurably for months. Another SRM strategy sometimes proposed is to increase the reflectivity of the Earth’s surface through widespread use of “white roofs.”

The potential benefits of many SRM strategies are offset by potential risks. In the case of aerosol injection strategies, for example, significant regional or global effects on precipitation patterns could occur,b potentially placing food and water supplies at risk. SRM alone would also do nothing to slow ocean acidification, since CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere and ocean would continue to rise. Thus, it is unclear if any of the proposed large-scale SRM strategies could actually reduce the overall risk associated with human-induced climate change.c Large-scale proposals for post-emission GHG management generally involve either removing CO2 from the atmosphere by direct air capture technologies or managing ecosystems on land or in the ocean to increase their natural uptake and storage of carbon. Strategies for enhancing carbon sequestration in soils and forests (which are often viewed as standard strategies for limiting climate change rather than geoengineering) are relatively well understood and offer important opportunities for reducing net GHG emissions in some parts of the world. However, changes in the sequestration rates of these systems are often difficult to quantify, and the potential effectiveness of these strategies may decline over time due to saturation effects.d A more controversial post-emission GHG management strategy which has actually been tested at small scales is fertilizing the ocean by adding iron to iron-poor waters (or adding other limiting nutrients or minerals) to increase removal of CO2 from the atmosphere by phytoplankton. Concerns have been raised both about the efficacy of this approach and about possible risks that it might pose to marine

Setting Goals

Concrete, quantitative goals for limiting the magnitude of climate change offer the benefit of allowing all parties involved to have a common sense of purpose and a clear metric against which to measure progress. Finding agreement on quantitative

ecosystems.e Other post-emission approaches involve removing CO2 from the air though chemical processes, but as with conventional carbon capture and storage from point emission sources, direct air capture schemes require reliable geological repositories for the removed CO2. In general, most CO2 removal approaches seem to pose fewer ancillary risks than SRM approaches, but they appear likely to be expensive, and because they would have only a gradual effect on atmospheric GHG concentrations, they would not have the potential to produce substantial cooling quickly.

Because some forms of geoengineering would have consequences that span national boundaries, international legal frameworks are needed to govern the development and possible deployment of these options. Such frameworks need to include a clear definition of the “climate emergency” that would trigger deployment of large-scale SRM, and criteria for whether, when, and how SRM (and some versions of post-emission GHG management) would be tested —recognizing that even the act of field testing may create international tensions. More fundamentally, intentional alteration of the Earth’s environment via geoengineering raises significant ethical issues, including the distribution of risks among population groups in both present and future generations, as well as challenging questions of public perceptions and acceptability.f

In conclusion, geoengineering approaches may conceivably have a role to play in future climate risk management strategies, particularly if efforts to reduce global GHG emissions are unsuccessful or if the impacts of climate change are unexpectedly severe. At present however, the costs, benefits, and risks of many geoengineering approaches are not well understood. In the committee’s judgment, it would therefore be imprudent to use certain geoengineering approaches (in particular, SRM and ocean fertilization strategies) to manipulate the Earth’s environment in the near future, and it would be unwise to assume they will be attractive options even in the more distant future. We recommend instead a program of research to better understand the potential effects of different geoengineering options and efforts to address the international governance issues raised by many geoengineering proposals.

______________

aSee, e.g., Royal Society, Geoengineering the Climate: Science, Governance, and Uncertainty, RS policy document 10/09 (London: The Royal Society, 2009); American Geophysical Union, Geoengineering the Climate System. A Position Statement of the American Geophysical Union (Adopted by the AGU Council on 13 December 2009); American Meteorological Society, Geoengineering the Climate System. A Policy Statement of the American Meteorological Society (adopted by the AMS Council on 20 July 2009).

bG. C. Hegerl and S. Solomon, “Risks of climate engineering” (Science 325[5943]:955-956, 2009, doi: 10.1126/science.1178530).

cSee NRC, Advancing the Science, Chapter 15 for additional discussion of proposed SRM approaches, including the research needed to better understand their potential efficacy and risks.

dSee NRC, Advancing the Science and Limiting the Magnitude for further discussion and references.

eK. O. Buesseler, S. C. Doney, D. M. Karl, P. W. Boyd, K. Caldeira, F. Chai, K. H. Coale, H. J. W. De Baar, P. G. Falkowski, K. S. Johnson, R. S. Lampitt, A. F. Michaels, S. W. A. Naqvi, V. Smetacek, S. Takeda, and A. J. Watson, “Environment: Ocean iron fertilization—Moving forward in a sea of uncertainty” (Science 319[5860]:162, 2008).

fNRC, Advancing the Science.

targets is, however, an inevitably contentious process, and a failure to reach consensus on such targets can become a barrier to moving ahead with meaningful actions. It is of course possible to proceed with meaningful actions to limit GHG emissions in the absence of universally-accepted quantitative goals. Nonetheless, it is important to understand the different types of goals that are being actively debated at national and international levels.

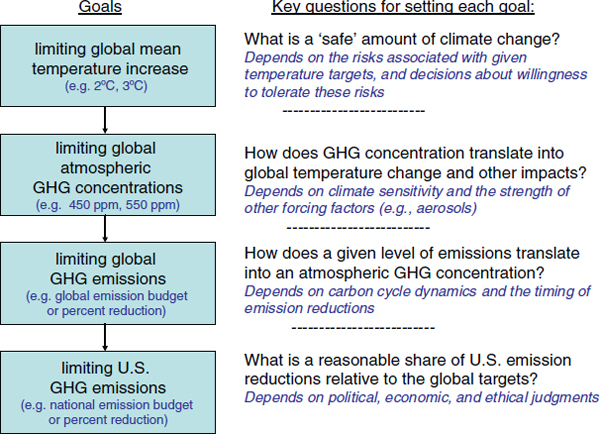

At the international level, a commonly discussed goal is the tolerable increase in global average surface temperature relative to pre-industrial times. (The goal of limiting global average temperature rise to 2°C (3.6°F) has been agreed to in a number of major international platforms,1 although there is ongoing scientific debate about whether that actually represents a “safe” threshold for limiting climate change.2) For any given global temperature goal, corresponding goals can then be derived for atmospheric GHG concentrations that would give a reasonable chance of meeting the temperature goal, for global GHG emissions limits that would give a reasonable chance of meeting those GHG concentration goals, and, finally, for national GHG emission limits that would collectively achieve the needed global emission reductions. These relationships are complicated, however, by a variety of scientific uncertainties and value judgments (see Figure 5.1).3

A global mean temperature limit is not a goal that can be directly controlled, but rather, is an emergent property of the decisions made by countless governments, private sector actors, and individuals around the world, and of the earth system processes that determine how emissions affect the earth’s climate. Operationally, domestic-level response strategies require metrics that can be directly tracked and controlled at the national level. For the U.S. national goal, the America’s Climate Choices (ACC) panel report Limiting the Magnitude of Future Climate Change recommends setting a “budget” for cumulative domestic GHG emissions over a set period of time—a recommendation the committee supports. The budget concept has also been proposed in the context of global emissions.4

It is beyond the mandate of this committee to recommend specific global or national emission budget goals because such goals are based in large part on value judgments about what is an acceptable degree of risk, and what is a fair U.S. share of the global emissions-reduction burden. Nor do we try to evaluate the risks of adverse climate impacts associated with different possible U.S. emission goals, because such risks ultimately depend on global emissions, not U.S. emissions alone. We do suggest, however, that in the context of iterative risk management, any such goals need to be periodically revisited and revised over time, in response to new information and understanding.

FIGURE 5.1 A schematic illustration of the steps involved in setting goals for limiting the magnitude of future climate change, and some key questions and uncertainties that need to be considered in each of these steps.

Reducing Global Emissions

The United States currently accounts for roughly 20 percent of global CO2 emissions, despite having less than 5 percent of the world’s population. The U.S. percentage of total global emissions is projected to decline over the coming decades, however, mainly because emissions from rapidly developing nations such as China and India will continue to grow (see Figure 3.1). International engagement challenges are discussed later in this chapter, but it is worth emphasizing here the central point that poorer nations usually find requests by the United States to limit their emissions unjustified for several reasons: because current per-capita emissions and standard of living in the United States and other developed nations are far above theirs, because the United States is responsible for the largest share of the historical increase in atmospheric GHG concentrations, and because the United States has not yet been willing to enact its

own national policies to limit emissions. As a result of such dynamics, the international community has not yet forged an agreement in which both developed countries and all large, rapidly developing countries commit to binding GHG emission reductions. Forging a comprehensive international agreement will be difficult and possibly infeasible without credible U.S. leadership, demonstrated through strong domestic actions.5

In addition to this need for demonstrating leadership through strong domestic actions, America’s climate change response strategies need to include cooperative international efforts aimed at helping developing countries advance their economies along less carbon-intensive pathways than were followed by today’s industrialized nations. This is primarily because reducing global GHG emissions requires limiting the growth in emissions from developing countries. Additional motivation comes from the fact that it is generally less expensive to reduce emissions in developing nations than in developed ones (although the evidence can vary considerably depending on the specific context),6 and because developing nations often present more significant opportunities for ancillary benefits such as reducing local air pollution.

Emission Offsets

Offsets can be used at either the domestic or international level to help lower the cost of reducing emissions. In most cases, an offset system allows actions that remove or prevent GHG emissions in one place to cancel (or offset) an equivalent amount of emissions elsewhere. Offsets can include investments in agriculture and land management, reforestation, energy efficiency, capture or destruction of industrial gases and methane, or low carbon energy generation such as renewables. International offset programs such as the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), that allow GHG emitters in the United States or other developed countries to pay for emission reductions in developing countries, can also be a potentially important mechanism for engaging those countries in emission-reduction efforts. Although the United States does not participate in the CDM, it has been involved in discussion of other international mechanisms similar to offsets, particularly proposals to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (often referred to as REDD).

The use of offsets can be complex and fraught with pitfalls, however. Some offsets, such as capturing methane from livestock waste, are relatively straightforward to quantify and implement. Others, such as sequestering carbon in soils and forests, or those where investments are made in small scale technologies such as improved wood stoves, present many challenges. Quantifying the size of the offset requires

not only knowing how much carbon is being sequestered by the system (which in turn requires accurate baselines and monitoring) but also knowing what would have happened in the absence of the offset program—i.e., offsets only contribute to reducing emissions if they are clearly additional to programs that would have been implemented anyway. In contrast, a cap-and-trade or carbon tax system (that does not allow use of offsets) considers only what actually is emitted; it does not require estimates, often controversial, of what would have been emitted absent the policy or action considered.

Offsets also raise concerns about emissions leakage: for example, if the demand for timber is unchanged (and there are no global emission caps), saving one forest that would have been cut could simply increase the pressure to cut other forests that would otherwise have been spared. A similar problem occurs with the so-called rebound effect, when savings from energy efficiency actions are invested in other activities that produce GHGs. Another complication arises from the fact that the amount of sequestered carbon can change over time. For instance, if a forest grown to offset carbon emissions from elsewhere burns down 10 years later, the emissions reductions provided by the offset will be lost.

Finally, the ancillary ecological and social impacts of offset programs can be either positive or negative, depending on whether they are guided by sound sustainable development or land management principles and practices, including respect for local property rights.7 For these reasons, the inclusion of offsets as a major component of U.S. climate policy will require rigorous rules, standards, and accounting procedures to ensure claimed emissions reductions are real and sustained.

Reducing U.S. Emissions

The nation’s efforts to reduce GHG emissions depend to a large degree on private sector investments (in areas such as technology development, physical assets, manufacturing operations, and marketing and delivery of goods and services) and on the behavioral and consumer choices of individual households. But federal, state, and local governments have a large role to play in influencing these key stakeholders through effective policies and incentives. In general, there are four major tool chests from which to select policies for driving GHG emission reductions:

- pricing of emissions by means of a tax or cap-and-trade system;

- mandates or regulations, which includes full-scale programs of controls on emitters (for example through the Clean Air Act) and more narrowly targeted mandates such as automobile fuel economy standards, appliance efficiency

standards, labeling requirements, building codes, and renewable or low-carbon portfolio standards for electric generation;8

- public subsidies through the tax code, appropriations, or loan guarantees; and

- providing information and education and promoting voluntary measures.9

A comprehensive national program would likely use tools from all four of these areas. Most economists and policy analysts have concluded, however, that putting a price on CO2 emissions (that is, implementing a “carbon price”) that rises over time is the least costly path to significantly reduce emissions and the most efficient means to provide continuous incentives for innovation and for the long-term investments necessary to develop and deploy new low-carbon technologies and infrastructure.10 A carbon price designed to minimize costs could be imposed either as a comprehensive carbon tax with no loopholes or as a comprehensive cap-and-trade system that covers all major emissions sources. (Pricing systems that are not comprehensive can also produce substantial reductions, though at higher per-ton costs.) Both of these could be effective tools; however, cap-and-trade policy offers the advantage of specifying emissions goals. Moreover, if several nations have cap-and-trade systems and international trading is permitted, firms in rich nations can reduce their costs—and total global costs—by paying for less expensive emissions reductions in other nations, rather than by making expensive reductions themselves.11

Meeting stringent national emission-reduction goals also requires the carbon price to rise to levels that are high enough to ensure the necessary investments are made in energy-efficient buildings and equipment, low-carbon energy production technologies, and other key areas, especially over the long run as stocks of equipment and infrastructure turn over. Estimating possible future carbon prices, which depends on many unpredictable factors, such as the pace of technology development, is beyond the scope of this study; but NRC, Limiting the Magnitude does contain a detailed discussion of future carbon price projections made in the recent multi-model studies of the Energy Modeling Forum.12

In addition to a price on carbon, there is a need for complementary policy measures that help to overcome market failures not fully addressed by a carbon price.13 Complementary policies may also be needed to overcome institutional barriers that inhibit responses to carbon prices and/or slow the penetration of new low-carbon technologies.14 Examples of such barriers include outdated building codes and regulatory systems15 and the information-related problems that reduce incentives for builders and home owners to invest in energy-efficient homes and appliances.16 Complementary policies must be chosen strategically, however—an optimal policy reduces emissions where it is cheapest to do so, not taking all possible measures, nor requiring all sectors

of the economy to participate equally. Limiting the Magnitude examines the types of complementary policies that are most useful for ensuring rapid progress in key areas such as household-level energy efficiency, development and use of renewable energy technologies, and retiring/retrofitting existing emissions-intensive equipment and infrastructure.

As a matter of political reality, a comprehensive carbon-pricing strategy of the sort described above may not be feasible in the near term. A strategy relying solely on other types of policies would involve higher costs but would still encourage near-term emission reductions and thus reduce the need to make costly reductions later. These policies range from relatively simple measures such as supporting R&D on low-carbon technologies and reducing behavioral and institutional barriers to energy efficiency, to more ambitious steps such as a nationwide renewable portfolio standard or a cap-and-trade system covering only electric power plants.17 To minimize the long-run costs of reducing emissions, however, it is important to avoid policies that may make it more difficult later (either economically or politically) to adopt a comprehensive carbon-pricing policy. This includes, for instance, policies that would implicitly or explicitly exempt some sources from a subsequent carbon tax or a broader emissions cap. It may also be necessary to avoid certain policies that have unacceptable equity and competitiveness impacts (see Box 5.2).

At the time of writing this report, the EPA is in the process of promulgating new rules to constrain CO2 emissions using the current authorities of the Clean Air Act. These rules, if adopted,18 will likely achieve emission reductions and may also stimulate innovation, but the regulatory strategy is not as likely as a well-crafted pricing strategy to provide continuous incentives to find the cheapest path to significant GHG reductions.19

RECOMMENDATION 1: In order to minimize the risks of climate change and its adverse impacts, the nation should reduce greenhouse gas emissions substantially over the coming decades. The exact magnitude and speed of emissions reduction depends on societal judgments about how much risk is acceptable. However, given the inertia of the energy system and long lifetime associated with most infrastructure for energy production and use, it is the committee’s judgment that the most effective strategy is to begin ramping down emissions as soon as possible.

Emission reductions can be achieved in part through expanding current local, state, and regional level efforts, but analyses suggest that the best way to amplify and accelerate such efforts, and to minimize overall costs (for any given national emissions

BOX 5.2

Equity and Competitiveness Issues

Significantly reducing U.S. GHG emissions, however it is accomplished, will produce “winners” and “losers” along several dimensions. Increasing the price of carbon-intensive energy, for instance, will have a disproportionate impact on those who need to drive long distances to work and residents of some coal-mining communities. Basic notions of fairness require that adverse energy price impacts on those least able to bear them be identified and addressed. Carbon-related revenues, obtained from carbon taxes or auctioning of emissions allowances in a cap-and-trade system, would provide resources that could be used for this purpose. Alternative or additional policy measures that make incentive-based climate change policies more accessible to low-income households (e.g., graduated subsidies or tax credits for home insulation improvements) may also be appropriate. Directly engaging economically disadvantaged and other vulnerable communities in the policy planning process helps allow the legitimate interests of those communities to be addressed, while nonetheless allowing broadly desirable investments to be made.

In an economy with substantial unemployment, expansion of labor-intensive activities like retrofitting buildings for increased energy efficiency can be an attractive option for increasing job opportunities.a A transition to a low-carbon economy would inevitably produce gains in some sectors and occupations and losses in others, and some studies suggest that such a transition will probably have only a small net impact on the overall level of U.S. employment.b For those sectors and regions that are at greatest risk of job losses, this transition could be smoothed through targeted support for education and training programs.

reduction target), is with a comprehensive, nationally uniform, increasing price on CO2 emissions, with a price trajectory sufficient to drive major investments in energy efficiency and low-carbon technologies. In addition, strategically-targeted complementary policies are needed to ensure progress in key areas of opportunity where market failures and institutional barriers can limit the effectiveness of a carbon pricing system.

If a pricing strategy proves to be politically infeasible, second-best approaches may include the expansion of regional, state, and local initiatives already under way, along with the adoption of national-level mandates or performance standards, some of which could potentially be implemented through the Clean Air Act. The committee suggests that new mandates and standards leave as much flexibility as possible for the private sector to choose the means necessary (i.e., the technological options) for meeting stated emission-reduction goals and leave room for later adoption of a pricing strategy.

Finally, de-carbonizing the U.S. energy system—or failing to do so—could have a significant impact on the competitiveness of some U.S. industries. The European Union (EU) has already increased its reliance on renewable energy and put a price on CO2 emissions from major sources, without detectable adverse economic effects.c China has now placed low carbon and clean energy industries at the heart of the country’s strategy for industrial growth, and is making large]scale public investments (for instance, in “smart grid” energy transmission systems) to support this growth.d If others continue to press in this direction but the United States does not, firms operating in the United States could find themselves increasingly out of step with the rest of the world, and without the robust domestic markets for climate-friendly products that their competitors in the EU and elsewhere would enjoy. Moreover, U.S. firms in energy-intensive sectors could be disadvantaged relative to their more energy-efficient foreign competitors if energy prices rise in coming decades (as many observers expect) regardless of whether global actions are taken to reduce GHG emissions. Firms operating in the United States might also face tariffs on their exports to countries that have emissions caps in place and are seeking to protect their industries from the competition posed by countries without such caps.

______________

aR. Pollin, H. Garrett-Peltier, J. Heintz, and H. Scharber, Green Recovery: A Program to Create Good Jobs and Start Building a Low-Carbon Economy(Washington, D.C.: Center for American Progress, 2008)

bNRC, Limiting the Magnitude; CBO, The Economic Effects of Legislation to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Budget Office, 2009); H. Huntington, Creating Jobs with Green Power Sources, Energy Modeling Forum OP64, (Stanford, CA: Stanford University, 2009).

cA. D. Ellerman, F. J. Convery, and C. de Perthuis, Pricing Carbon: The European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

dhttp://www.energychinaforum.com/news/42628.shtml (accessed Feb.20, 2011).

Finally, as with all elements of an iterative risk management strategy, actions taken to reduce GHG emissions need to be carefully monitored. Decisions made today (e.g., regarding emission targets, price schedules, sectors chosen for special attention) will require periodic reevaluation in light of new developments in climate science, in technological capabilities, in costs, and in understanding the impacts of response policies themselves (for instance, understanding how a carbon pricing system implemented in a less than comprehensive form will actually influence investments). In this regard, long-term emissions goals that stretch out for decades are useful and probably necessary but would likely need to be revisited over time. This need for the capacity to adjust polices in response to new information and understanding must be balanced against the need for policies to be sufficiently durable and consistent to attract substantial investment and encourage long-term changes in behavior. There is a natural tension between these goals and designing mechanisms to provide both durability and flexibility poses a key challenge for climate change governance.

REDUCING VULNERABILITY TO CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS

Even if substantial global GHG emissions reductions are achieved, human societies will need to adapt to some degree of climate change. In the committee’s judgment, choosing to do nothing now and simply adapt to climate change as it occurs, perhaps by accepting losses, would be an imprudent choice for a number of reasons. Even moderate climate change will be associated with a wide range of impacts on both human and natural systems (see Chapter 2), and the possibility of severe climate change with a host of adverse outcomes cannot be ruled out (especially if GHG emissions continue unabated). Moreover, as climate change progresses, unforeseen events may pose serious adaptation challenges for regions, sectors, and groups that may not now seem particularly vulnerable. Thus, just as the committee recommends that America embark on a course of substantial emission reductions, we recommend that America take proactive actions to mobilize the nation’s capacity to adapt to future climate changes. This dual-path strategy will reduce the risks of future climate-related damages more than pursuing either path alone.

Mobilizing Now for Adaptation

As discussed in NRC, Adapting to the Impacts, proactive adaptation involves preparing for the impacts of projected local and regional changes in climate before they occur. Examples of such changes (also described in Chapter 2 and references therein) include reduced surface water supply in America’s rapidly growing western regions and increased vulnerability of the Gulf Coast to sea level rise, especially in low-lying areas that are already subject to land subsidence and other environmental changes. Global climate models can provide robust projections of changes in some regions (such as reduced precipitation across the southwestern United States), and there are a variety of efforts under way to “downscale” this information to local and regional levels. Currently, however, models are limited in their ability to reliably project many of the local and regional scales that are critical for adaptation decisions; and this situation is only expected to improve gradually as computer power and scientific understanding advance.20 Regardless, efforts to assess adaptation needs at these scales can help indicate possible risks and key vulnerabilities.

Many types of decisions would benefit from improved insight into adaptation needs and options, but most notable are decisions with long time horizons. These include, for instance, decisions about siting of facilities, conserving natural areas, managing water resources, and developing coastal zones. In these realms, adaptation to climate change is less about doing different things than about doing familiar things differently. For

example, throughout history, governments have typically designed and managed water supply systems based (either implicitly or explicitly) on the assumption that future climate conditions will be similar to those experienced in the past. Proactive adaptation to climate change will require these decisions to account for the strong possibility that future climate conditions will be unlike the past (see Box 5.3). Many investments in adaptation will be largely inseparable from routine investments in infrastructure development and upgrading.

Because specific local or regional climate changes often cannot be precisely predicted, long-lived investments whose value may be affected by future climate change are inherently risky. Decisions about such investments accordingly become exercises in risk management. When climate models make differing predictions for a given locality, for example, it is prudent to seek robust options that will lead to acceptable outcomes across the full range of plausible future climate change scenarios (including low-probability but high-risk scenarios). An iterative risk management approach to adaptation also requires effective monitoring and assessment of both emerging impacts and the effectiveness of adaptation actions.

In many cases, adaptation options are available now that both help to manage longer-term risks of climate change impacts and also offer nearer-term co-benefits for other development and environmental management goals (see NRC, Adapting to the Impacts for examples). Experience to date indicates that if adaptation planning is pursued collaboratively among local governments, private-sector firms, nongovernmental organizations, and community groups, it often catalyzes broader thinking about alternative futures, which is itself a considerable co-benefit.

An Effective National Adaptation Strategy

Much of the work of adaptation will be done by state, local, and tribal21 governments, private-sector firms, nongovernmental organizations, and representatives of especially vulnerable regions, sectors, or groups. Decision makers at these levels often lack the resources necessary to perform this work effectively or lack experience in accessing and using information that may be available to inform their decisions. Dealing with vulnerabilities that cross geographic, sectoral, or other boundaries are particularly challenging. Although early adaptation planning is beginning to emerge from the bottom up in the United States, it is hampered by a lack of both knowledge and resources.22

The federal government can play a valuable leadership and coordination role for adaptation. In the near term, this includes initiating the development of a national (i.e.,

BOX 5.3

Adapting to Changing Precipitation Patterns

Different regions of the United States face different types of risks from climate change, thus requiring very different adaptation strategies. Responses to the potential impacts of changing precipitation patterns provide illustrations of these challenges. Climate models generally predict that across the United States, precipitation will increase in northern regions and decrease in the southern and western states. Below are two examples of the different adaptation challenges posed by such changes.

Vulnerability of Mass Transit in New York City to Extreme Precipitation Events. New York City experiences substantial precipitation in all months of the year. Mean annual precipitation has increased slightly over the course of the past century, and inter-annual variability has become more pronounced. Climate models project that in the coming decades, the city will experience an increasing number of heavy rainfall events (for example, the number of days per year where rainfall exceeds 1 inch, 2 inches, or 4 inches).a Many components and facilities of rail systems in New York City, such as public entrances and exits, ventilation facilities, and manholes, were built at low elevations. For example, in upper Manhattan parts of the subway system are as much as 180 feet below sea level. Large sections of the system are thus vulnerable to flooding from such heavy precipitation events as well as from sea level rise.b

On August 8, 2007, heavy precipitation from a major storm resulted in a system-wide outage of New York City subways during the morning rush hour. Before the system could re-open, eight tons of debris had to be removed and a variety of equipment had to be repaired or replaced.c More frequent events like this one can be expected to increase the frequency of transit interruptions unless proactive adaptation steps are taken.The Metropolitan Transit Authority has subsequently invested significantly in the distribution of large pumps throughout the system to reduce sensitivity to extreme precipitation, and the city is also planning investment strategies to reduce exposure.

not just federal) adaptation strategy that engages a broad range of decision makers and stakeholders. An important initial step in developing such a strategy is to identify key vulnerabilities to plausible climate changes, which will vary substantially from place to place and among parties within each place. Basic notions of fairness suggest that special near-term consideration be given to identifying and developing adaption strategies for especially vulnerable populations.

Another important federal role is to provide key resources (e.g., scenarios, visualization tools, methods, data) to support vulnerability analyses. There is currently no widely-accepted approach for conducting vulnerability assessments, and much of the data and scientific infrastructure needed to make these assessments robust are lacking. Yet another important component of a national adaptation strategy is to evaluate existing

Projected Changes in Precipitation and Runoff in the Southwest. As a result of climate change, it is projected that the southwestern states will face an overall reduction in average annual precipitation, with corresponding reductions in runoff in the Upper and Lower Colorado River. Recent estimates suggest a reduction of roughly 6 percent for each degree of increase in global mean temperature over the coming century or beyond.d The southwest region has long struggled with issues of water availability as population has grown,e and the challenges of coping with scarce water resources in this region will only be exacerbated by declines in future water availability due to climate change. A study of potential climate change impacts on the Colorado River system (a system that roughly 30 million people depend upon for drinking and irrigation water) finds that climate changes occurring over the next several decades would increase the risk of fully depleting water reservoir storage far more than the risk expected from population pressures alone. A scenario of 20 percent reduction in the annual Colorado River flow due to climate change results in a near tenfold increase in the probability of annual reservoir depletion by 2057 —a huge water management challenge.f

______________

aNew York City Panel on Climate Change,Climate Risk Information (New York: New York City Panel on Climate Change, 2009).

bNYCSubway.org, June 24, 2005, http://www.nycsubway.org/perl/stations?207:2659 (accessed July 15, 2009).

cMetropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), August 8, 2007 Storm Report. New York: Metropolitan Transportation Authority, 2007, p. 34.

dNRC, Stabilization Targets, Table 5.3.

eSee, e.g., NRC, Colorado River Basin Water Management: Evaluating and Adjusting to Hydroclimatic Variability (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2007).

fB. Rajagopalan, K. Nowak, J. Prairie, M.Hoerling, B. Harding, J.Barsugli, A. Ray, and B. Udall, “Water supply risk on the Colorado River: Can management mitigate?” (Water Resources Research 45:W08201, 2009, doi:10.1029/2008WR00765).

state and federal policies (many involving infrastructure and land use) in light of current knowledge about projected future changes in climate.23

Effective federal government leadership means ensuring that federal programs, activities, and planning take climate change into account and, in particular, that maladaptive policies and practices be identified and reformed. This includes, for instance, revising the current definition of the 100-year floodplain.24 The federal government will also need to take steps to ensure that the national adaptation strategy will be implemented effectively and revised in light of new knowledge. A variety of decision-making processes at all levels will need to be redesigned to ensure that the latest information regarding future climate change is taken properly into account going forward. The exchange of information at the state, local, and tribal levels and between

the public and private sectors may be particularly valuable. It will also be important to institutionalize coordination among the many federal agencies with resources and authorities relevant to adaptation and to implement durable research and training programs aimed at enhancing the capability of nonfederal governments and the private sector to adapt to future climate change.

Internationally, the impacts of climate change will disproportionately be felt in those developing nations that lack both the necessary expertise and financial resources for critical investments.25 The potentially destabilizing impacts of climate change in the developing world have been identified by military and security analysts as a national security issue for the United States. Such impacts also pose a humanitarian concern should climate change, for example, lead to increases in the occurrence or severity of natural disasters. There are also economic implications should climate change affect consumers of key exports or regions of critical food production and other imports. It would thus be prudent for the federal government to support efforts to enhance adaptive capability in the developing world, as well as within the United States. These and other international concerns are further discussed later in the chapter.

Like the challenge of reducing GHG emissions, the challenge of adaptation will be with America for decades. Accordingly, federal efforts need to include not just formulating an initial national adaptation strategy but also creating durable institutions (or in some cases, strengthening existing institutions) that can revise and improve that strategy over time, in light of new knowledge and new policy options.

Regardless of whether the federal government plays this leadership and coordination role in the near term, it would be prudent for nonfederal government leaders, the private sector, and nongovernmental organizations to take proactive steps to reduce vulnerability to climate change, through for instance, vulnerability assessment and investments in preparedness and disaster response. In addition, “horizontal” coordination among subfederal governments and the private sector can help facilitate the efforts of all participants. There is a role as well for nongovernmental organizations that provide expertise and help catalyze the needed coordination.

RECOMMENDATION 2: Adaptation planning and implementation should be initiated at all levels of society. The federal government, in collaboration with other levels of government and with other stakeholders, should immediately undertake the development of a national adaptation strategy and build durable institutions to implement that strategy and improve it over time.

INVESTING TO EXPAND OPTIONS AND IMPROVE CHOICES

A sound strategy for managing climate-related risks requires sustained investments in developing new knowledge and new technological capabilities as well as investments in the institutions and processes that help ensure such advances are actually used to inform policy decisions. There is, in particular, an important role for federal support of basic climate-related research and pre-commercial technology development, because private firms and individuals typically do not stand to benefit commercially from, and thus are unlikely to invest in, such efforts. As discussed below, improved coordination among the federal agencies involved, and between domestic and foreign research efforts, can increase the returns on research spending.

Advancing Scientific Understanding and Technological Development

As discussed in NRC, Advancing the Science, scientific research in the United States and around the world has greatly enhanced our understanding of climate change and its causes and effects. The U.S. Global Change Research Program has played an important role in this effort. However, because important questions remain unanswered and because the stakes are so high, it is imperative to continue research, in both the biophysical and social sciences, aimed at increasing our understanding of climate change processes, enhancing our ability to predict climate change and its impacts on critical systems (e.g., agriculture, water resources, urban infrastructure, ecological systems), and increasing our understanding of how people and institutions are affected by and respond to those impacts.

Together with research that enhances fundamental understanding of the climate system, there is a need for research that generates additional options for limiting climate change and adapting to its impacts, and research on how to effectively inform decision making through decision support tools and practices. For example, the development of new technologies for reducing GHG emissions should be accompanied by studies aimed at understanding barriers to their implementation. Adaptation responses can be improved through research on methods for assessing vulnerability and on integrative approaches for responding to the impacts of climate change in interaction with other stresses.

Improving observational and monitoring systems, and developing mechanisms that ensure relevant results are available to key decision makers, can yield a substantial return in the form of better decisions (conversely, in the absence of such information, important decisions would have to be made while “flying blind”). Future decision-

support efforts can be improved by research on risk communication and risk management processes, by improved understanding of the factors that facilitate or impede decision making, and by analysis of information needs and existing decision-support activities. Among other things, these efforts will require the development and testing of new analytical approaches and integrative models.

If GHG emissions are to be substantially reduced in a growing U.S. economy, research on climate-friendly energy technologies, and factors affecting their adoption, must be an important element of the nation’s R&D portfolio. It often takes decades to bring new energy technologies to market and to deploy them widely, and thus in the near term the U.S. energy system will necessarily rely on technologies that are in (at best) pre-commercial development today. Because the benefits of basic research or pre-commercial technology development in the energy sector cannot be completely captured by the entity that performs it, federal government support of these activities is appropriate, while at the same time recognizing that it is important for government R&D dollars be spent with a willingness to take risks and to focus on long-term benefits.

The federal government plays an essential role in the development of climate-friendly technologies, but government programs are generally ill-suited for translating research results into commercial products. Those final stages of the innovation process are almost always best left to the private sector. But the private sector will not invest significant resources in the design and marketing of climate-friendly products unless it can reasonably expect that there will be demand for them. Because the climate-related benefits of low-carbon technologies are not reflected in market prices, without a substantial and rising carbon price, or some other guarantee of a commercial market, the private sector is likely to under-invest in bringing new low-carbon technologies to market. There is likewise a need, in some instances, for policies to help overcome obstacles to technology commercialization. For example, large-scale demonstration programs may be necessary to reduce uncertainties regarding the cost of newnuclear generating units. Similarly, the large-scale deployment of carbon capture and storage would require the creation of a comprehensive legal framework governing the transportation and underground storage of CO2.

Research on adaptation is another important component of a balanced R&D portfolio. Just as it is appropriate for the federal government to support research on earthquake-resistant building codes (that can be applied by many local governments, none of which could afford the cost of such research alone), so it is appropriate for the federal government to support research on standards for the design of roads, bridges, and other structures that will perform well under a variety of possible future climates.

Other important adaptation-related research topics include, for instance, improving methods for assessing vulnerability and developing crop varieties and farming methods that can perform well in a range of possible future climate conditions.

RECOMMENDATION 3: The federal government should maintain an integrated, coordinated, and expanded portfolio of research programs with the dual aims of increasing our understanding of the causes and consequences of climate change and enhancing our ability to limit climate change and to adapt to its impacts. In order for federal spending on climate-related R&D to yield optimal returns, it must be effectively coordinated across the many different federal agencies involved, and funding must be relatively stable over time.

Making New Knowledge Pay Off Through Effective Information Systems

An effective national response to climate change demands informed decision making that is based on reliable, understandable, and timely climate-related information tailored to the needs of decision makers in different levels of government, the private sector, educators, and the public. Information systems and services are essential to the effective management of climate risks, because they allow decisions to be modified in response to changing conditions and new information through ongoing evaluation and assessment of policies and actions. Good information systems also underpin effective communication.

NRC, Informing Effective Decisions identifies several key aspects of information support to help decision makers develop effective responses to climate change, including the following:

- Information on climate change, vulnerability, and impacts in different regions and sectors is needed for formulating adaptation strategies and understanding how GHG emissions reductions may reduce risks.

- Institutions and mechanisms for “climate services” (i.e., the timely production and delivery of useful climate data, information, and knowledge to decision makers) must respond to the needs of users, be understandable and easily accessible, and be based on the best available science.

- Information for GHG management and accounting—such as establishing emission baselines and supporting monitoring, reporting, and verification—are essential to legitimize market-based systems, as well as voluntary commitments by governments and the private sector.

- Information on energy efficiency and GHG emissions (e.g., conveyed through

product labeling) can help encourage consumer purchasing and behavioral changes.

- Public communication must rest on high quality information that clearly conveys climate science and climate choices and that is seen as coming from trusted sources.

- Because many climate-related choices are occurring in an international context (e.g., in the case of global agricultural and trade systems)—it is essential for the United States to support international information systems and assessments.

In a policy area as complex and rapidly changing as climate change, sound iterative risk management requires institutions with the ability and responsibility to monitor new learning and to make it available in understandable, relevant form to decision makers in the public and private sectors. There is much to be gained by sharing information about what works and does not work, both within the United States and internationally. Existing institutions perform some of these functions, but none provides an ideal model for performing the range of tasks described above, and few effectively engage nonfederal actors.

There are a variety of mechanisms that could be developed for carrying the sort of periodic reporting effort described above. NRC, Limiting the Magnitude suggests, as one example, a process in which the President periodically reports to Congress on key developments affecting our nation’s response to climate change. This process can be seen as analogous to the Economic Report of the President, prepared annually by the Council of Economic Advisers. It could build upon existing mechanisms for periodic reporting on climate change information (e.g., the annual GHG emissions inventory carried out by the EPA, the U.S. Climate Action report organized by the State Department as input to the UNFCCC, the Our Changing Planet report compiled by the USGCRP), and it may include updates on factors such as:

- national and global emissions trends, and their relationship to developments in our understanding of climate change science (including reporting on whether the United States is making sufficient progress toward meeting its GHG budget);

- energy market developments and trajectories;

- the implementation status, costs, and effectiveness of GHG emission-reduction policies;

- the status of the development and deployment of key technologies for reducing GHG emissions;

- the distributional consequences of emission-reduction policies across income groups and regions of the country;

- developments in understanding of climate change impacts and vulnerability to those impacts; and

- updates of adaptation plans and actions underway at federal, state, and local levels.

A wide array of actors in state and local governments, nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector are already playing important roles and should continue to be involved, in the enterprise of collecting and sharing climate-related information (see NRC, Informing Effective Decisions for details). But there are a number of areas where federal-level leadership is of particular importance. This includes, for instance, the issuance of federal guidelines for gathering and reporting of key climate-related information, to help ensure the legitimacy and comparability of information being collected by different parties. It also includes monitoring relevant developments internationally and ensuring information access for especially vulnerable populations. Current examples of federal leadership include NOAA and NASA’s roles in collecting basic observations of atmospheric, oceanic, and land-surface changes (with regional and private sector actors adding local detail and value-added products); and the EPA’s role in collecting and evaluating emission inventory data. Such efforts are clearly valuable in national debates about whether climate change is happening, and whether responses are effective.

RECOMMENDATION 4: The federal government should lead in developing, supporting, and coordinating the information systems needed to inform and evaluate America’s climate choices, to ensure legitimacy and access to climate services, greenhouse gas accounting systems, and educational information. To help garner public trust, the design and implementation of any such information systems should be transparent and subject to periodic independent review.

Engaging the Broader Community

As discussed in Chapter 4, establishing processes that bring together scientific / technical experts and government officials with key stakeholders in the private sector and the general public is essential for the success of an iterative risk management approach to addressing climate change. This is because these other stakeholders make important contributions to mitigation and adaptation efforts through their daily choices; because they are an important source of information and perspectives in assessing policies options and in setting priorities for research and development; and because they determine the direction and viability of most governmental policies over the long term.

Processes for engaging stakeholders in learning and deliberation take many forms (for example, Box 4.2 discusses the value of analytic deliberative processes). A substantial research literature, summarized in a number of NRC reports, identifies design principles and tools for implementing such engagement processes. These principles include, for instance, the need to be collaborative and broad based, to combine deliberation with analysis, to ensure transparency of information and analysis, to attend to both facts and values, to explicitly address assumptions and uncertainties, to provide a means of inquiring into official analyses, and to allow iterative reassessment of prior conclusions based on new information.26 Federal agencies and other organizations that can provide scientific analyses for informing climate choices could do so through direct engagement with the regions, sectors, and constituencies they serve. There are many examples already under way, ranging from national networks such as NOAA’s Regional Integrated Science and Assessment Centers to ad hoc community-level dialogues.

RECOMMENDATION 5: The nation’s climate change response efforts should include broad-based deliberative processes for assuring public and private-sector engagement with scientific analyses, and with the development, implementation, and periodic review of public policies. Such processes can be initiated by federal agencies, state or local governments, the private sector, or non-profit organizations—linking the organizations that can provide relevant scientific analyses with the constituencies they are best suited to serve, and engaging those who are most affected by a given decision.

The United States has a strong national interest in ensuring an effective global response to climate change, because if domestic GHG emissions reductions are to be effective in actually limiting climate change, they must be accompanied by significant emission reductions from all major emitting countries. Also, the United States can be deeply affected by climate change impacts occurring elsewhere, given the degree to which different nations are linked by shared natural resources (e.g., fisheries, cross-border river systems), migration of species, diseases vectors, and human populations, and linked economic and trade systems. The United States can magnify the returns on its climate-related investments by a thoughtful strategy of international engagement that encompasses all the various activities discussed in earlier sections of this chapter.

In the committee’s judgment, serious U.S. emission-reduction efforts and effective participation in international negotiations are necessary conditions for stimulating sub-

stantial global emission reductions. The difficult and unwieldy nature of the UNFCCC process underlies the need for U.S. diplomatic efforts to be enhanced by continued involvement in the Major Emitters Forum and other bilateral and multilateral settings. As discussed earlier, the use of international offsets, in which a U.S. firm pays for and receives credit for relatively inexpensive emissions reductions (relative to some baseline) in another country, may play a constructive role in engaging developing nations; but only experience will tell if these approaches will be sufficient to induce substantial global emissions reductions.

International agreements to limit GHG emissions (and to enhance GHG sinks through land-use practices) will require rigorous methods to accurately estimate these emissions, monitor their changes over time, and verify them with independent data. To help assure that such efforts are carried out with transparency, consistency, and proper quality assurance in all countries, there is a need for active U.S. participation in international cooperative efforts, including financial and technical assistance for developing countries that lack the needed resources and expertise. In 2010, the NRC assessed existing capabilities for estimating and verifying GHG emissions and identified ways to improve these capabilities through strategic near-term investments.27

The United States also has much to gain from actively participating in international adaptation efforts, particularly those involving developing nations. It is in the nation’s interest to limit the potentially destabilizing impacts of climate change in the developing world, and it can be argued that our large contribution to current and historic global GHG emissions gives us some responsibility to assist those whose vulnerabilities exceed their resources. Moreover, active U.S. participation in international adaptation programs could enable us to learn from the effective programs of others. Some efforts could be collaborative, such as research on drought-resistant agriculture for tropical regions. Some efforts might be carried out through existing treaties and development assistance programs, for instance, various UN and World Bank programs, as well as existing UNFCCC adaptation funding programs. Additional mechanisms may be needed, however, for multilateral exploration of techniques and technologies that support adaptation, as well as for communication and trust-building. Durable institutional arrangements will be necessary for long-term success.

The United States also has much to gain from international engagement in scientific research and technology development. Understanding and responding to the risks of climate change requires ongoing efforts to collect and evaluate a vast array of information from around the world. In addition to observations of the climate itself, this includes data on relevant socioeconomic indicators, on emissions monitoring and verification activities, and on best practices in climate change limiting and adaptation

efforts. Some relevant information can be gathered by top-down physical observations (e.g., satellite remote sensing), but some will require the bottom-up collection and synthesis of detailed local-scale monitoring. Almost all such efforts are beyond the means of any single country and can only be effectively advanced through international cooperation, in which U.S. leadership could well prove critical.

Carefully targeted and coordinated R&D efforts can help enable developing nations to achieve both the economic growth necessary to alleviate poverty and the GHG emissions reductions necessary to limit future climate change. If today’s poor nations rely only on currently available technologies in their drive to approach the living standards of today’s rich nations, dramatic increases in global CO2 emissions are inevitable. To reduce global emissions, developing nations must travel a less carbon-intensive development path; and it is in U.S. interest to help facilitate their efforts to follow these alternative paths. In addition, U.S. firms could gain valuable technology and market access from participation in international efforts to develop low-carbon technologies.

RECOMMENDATION 6: The United States should actively engage in international-level climate change response efforts: to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through cooperative technology development and sharing of expertise, to enhance adaptive capabilities (particularly among developing nations that lack the needed resources), and to advance the research and observations necessary to better understand the causes and effects of climate change.

TOWARD AN INTEGRATED NATIONAL RESPONSE

The different types of actions presented in this chapter as part of America’s climate choices are not separate and distinct. Rather, actions in one category can directly affect actions in others—for better or for worse. For example, the more successful efforts are to reduce GHG emissions, the less climate change there will be to adapt to, and the more time will be available to adjust. The more we advance basic understanding of the climate system, the more effective our responses will be. Table 5.1 illustrates these and other linkages among the different elements of a comprehensive response strategy. A comprehensive national response strategy that effectively integrates these different elements, however, presents significant challenges of coordinating across different levels of government, across different types of organizations (within and outside government), and across different types of response functions. Each of these challenges is discussed below.

TABLE 5.1 Matrix of Interdependencies Among the Different Elements of a National Response to Climate Change

| Will strengthen this element because… | |||||

| Limiting | Adapting | Advancing Science & Technology | Informing | ||

| Advancing this element… | Limiting | There may be less stringent, disruptive requirements (and thus lower costs) for adapting to climate change impacts. | There may be less pressure to develop risky and/or expensive technologies for coping with impacts. | The decision environment may be less contentious if the severity of climate change can be limited. | |

| Adapting | Any given degree of climate change may be associated with less severe impacts and disruptions of human and natural systems. | There may be less pressure to develop risky and/or expensive technologies for limiting climate change (e.g., some forms of geoengineering). | The decision environment may be less contentious if communities and key sectors are prepared to deal with impacts. | ||

| Advancing Science & Technology | R&D could help identify more and better options for limiting climate change. | R&D could help provide more adaptation options and more knowledge about their implications. | The knowledge base for informing decisions may be more complete, and the knowledge base about how to most effectively inform may allow better information flow. | ||

| Informing | Effective options for limiting climate change may be more widely deployed and used. | Effective options for adapting to climate change may be more widely deployed and used. | Science may be more attuned to decision needs, and public support for advances in science is likely to increase. | ||

Coordination Across Levels of Government

Efforts to limit and adapt to climate change present different types of coordination challenges. Adaptation choices will be made largely by state and local governments and the private sector. The federal government can play an important leadership role by providing widely useful knowledge and information, but an effective national adaptation strategy will be based not on top-down federal directives. Rather, it will be based on coordination and information sharing across levels of government and between public and private sectors.

The federal role is more obviously and critically important in limiting GHG emissions. The relevant domestic costs and benefits can be fully aggregated only at the national level, and strong federal action will be necessary to achieve large U.S. emission reductions and to sustain an effective, balanced R&D program. Nevertheless, many states and localities have taken significant early steps to limit emissions, and some important limiting options, such as revising building codes, changing land-use patterns, and reconfiguring transportation systems, are within the traditional authority and expertise of state and local governments.

Effective coordination requires carefully balancing federal with state and local authority and promoting regulatory flexibility across jurisdictional boundaries where it is sensible to do. This includes, for instance, allowing states the option of regulating GHG emissions more stringently than federal law (in which case, the state is shifting more of the burden of meeting national goals onto its own residents). There is generally little to be gained by preempting such state regulations, as long as one can avoid standard-setting that fragments the national market among numerous states with differing regulations. Perhaps most importantly, efforts of state and local governments to reduce GHG emissions or adapt to climate change provide valuable policy experiments from which decision makers at other levels can draw useful lessons.

Coordination can also take the form of providing federal incentives (or removing disincentives) for action by states and localities. This includes, for instance: ensuring that states and localities have sufficient resources to implement and enforce significant new regulatory burdens placed on them by federal policy makers (e.g., national building standards); ensuring that new federal directives do not disadvantage states and localities that have taken early action to reduce emissions; and providing incentives for adaptation planning across jurisdictions and sectors.

Coordination Across Organizations

Dozens of federal agencies and other organizations are carrying out research, making decisions, and taking action on climate change through a host of existing programs and authorities. These include, for example, adaptation on federal lands (Departments of Agriculture, Interior, and Defense); research on climate change and related impacts (many agencies); research and development for technologies to respond to climate change (Department of Energy); information provision (Energy Information Administration, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Environmental Protection Agency); and regulation of automobile efficiency and GHG emissions (Department of Transportation, Environmental Protection Agency). Many additional organizations will likely engage as national strategies for limiting and adapting to climate change emerge.

Although the various activities carried out through these different programs are inextricably linked, they are managed largely as separate, isolated activities across the federal government. For example, many departments and agencies that are or will be engaged in climate response (e.g., Federal Emergency Management Agency, Department of Housing and Urban Development, Department of Energy) have not been part of the U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP) and lack sufficient communication with the federal agencies that are developing knowledge they need. The USGCRP and the Climate Change Adaptation Task Force have largely been confined to convening representatives of relevant agencies and programs for dialogue, without mechanisms for making or enforcing important decisions and priorities. Moreover, even the USGCRP and the Climate Change Technology Program together do not appear sufficient for effectively coordinating the full portfolio of research needed to support climate change response efforts.

One can look to other major policy arenas (e.g., public health, national security) and to other countries for examples of different coordinating mechanisms that have been employed with varying degrees of success. Some common models include:

- Giving one federal agency full responsibility and authority to lead and coordinate activities across the federal government (e.g., as has occurred with climate change in the United Kingdom and Australia);

- Creating a White House staff position tasked with directly advising the President on policy decisions and leading coordination efforts (e.g., a climate “czar”);

- Establishing a new executive branch organization, staffed by senior-level officials from other relevant government bodies, responsible for coordinating policy and advising the President (e.g., the National Security Council model).

A detailed evaluation of the pros and cons associated with each of these different organizational models is beyond the scope of this report, but the next section discusses the general capabilities and responsibilities that would be most important for any such coordinating entity.

Coordination Across Functions

Many previous NRC studies have offered guidance on how to ensure that decision makers are informed by the best relevant scientific and technical analysis;28 but in the context of climate change, efforts to actually do so are in their infancy. Traditionally, climate change research efforts have been organized predominantly around priorities defined by advancing scientific understanding, which do not necessarily match the needs of affected decision makers. Meeting the coordination challenge of linking knowledge to action will require sustained efforts from decision makers at all levels, but there is a particularly strong need for federal leadership. Federal agencies can create organizations to perform coordination functions for particular regions or sectors, as NOAA has done with its Regional Integrated Sciences and Assessments Program, and DOI is planning to do with its Landscape Conservation Councils and Climate Science Centers. They can also support networks that link decision makers within a region or sector to each other and to decision-relevant knowledge, can facilitate processes to collect and analyze data on climate response efforts around the country, and can communicate the lessons from objective assessments of these efforts, thus enabling decision makers to learn from each other’s experiences.

In summary, the following are some essential coordination challenges that a national climate change response effort will need to address:

- Ensuring that federal actions facilitate (or at a minimum, do not impede) effective nonfederal actions for mitigation and adaptation;

- Developing a clear division of labor among federal agencies and a process to monitor how well this division of labor is functioning over time;

- Ensuring decision support for constituencies that do not have a particular government agency or program responsible for providing such information; and

- Linking science, decision support, and resource management functions within the federal response to climate change.

To address such wide-ranging challenges, any institution with major responsibility for coordinating our nation’s climate change response efforts will need to have several key features, including: authority to set priorities and to turn these priorities into

resource allocation decisions; sufficient budgetary resources to actually implement allocation decisions; personnel who both understand climate science and understand the needs of climate-affected decision makers; mechanisms for monitoring the organization’s performance, in order to improve over time; and processes to ensure accountability to the parties that use information developed or shared by the institution.

RECOMMENDATION 7: The federal government should facilitate coordination of the many interrelated components of America’s response to climate change with a process that identifies the most critical coordination issues and recommends concrete steps for how to address these issues. Coordination and possible reorganization among federal agencies will require attention from the highest levels of the executive branch and from Congress. In areas of mixed federal and non-federal responsibility, the federal government’s leadership role should emphasize support and facilitation of decentralized responses at lower levels of government and in the private sector.

CHAPTER CONCLUSION

Responding to the risks of climate change is one of the most important challenges facing the United States today. Unfortunately, there is no “magic bullet” for dealing with this issue; no single solution or set of actions that can eliminate the risks we face. America’s climate choices will involve political and value judgments by decision makers at all levels. These choices, however, must be informed by sound scientific analyses. This report recommends a diversified portfolio of actions, combined with a concerted effort to learn from experience as those actions proceed, to lay the foundation for sound decision-making today and expand the options available to decision makers in the future. Doing so will require political will and resolve, innovation and perseverance, and collaboration across a wide range of actors.