3

Evolution of the Occupational Classification System

The 1991 Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT) classified and described over 12,000 occupational titles, each representing a larger group of more specific jobs. Viewing data collection for this many occupational titles as expensive and time-consuming, both the National Research Council (1980) and the Advisory Panel for the Dictionary of Occupational Titles (1993) recommended that the “new DOT,” which became O*NET, should cluster larger numbers of specific jobs into a smaller number of occupational categories. The current O*NET classification system defines and describes 1,102 occupations and is aligned with the system used by all federal agencies that gather occupational information, the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) system.

The close correspondence between O*NET and SOC allows users of O*NET to access all of the six “windows” in the O*NET content model, including “workforce characteristics” (Figure 1-1). Information on workforce characteristics is provided to O*NET users through links to Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data and other state and local data that are gathered using the SOC classification system.

Since the inception of the O*NET system in 1998, both users and non-users of the data have often expressed a need for information about more narrowly defined occupations. Requests to include more specific occupations continue today. For example, when the Office of Management and Budget requested public comments on the U.S. Department of Labor’s (2008) request for approval to continue collecting data for three years, a group of economists and workforce development specialists requested that the O*NET occupational classification system break out Information

Technology occupations and “green” occupations—that is, those associated with conservation of energy and environment, the production of energy from nontraditional sources, and creation of products that are ecologically friendly—in greater detail (Reamer et al., 2009). A representative of the Social Security Administration told the committee that O*NET is not useful for this agency’s process of disability determination because it does not break out occupations in enough detail and also because it does not include detailed information on physical abilities (Karman, 2009). Human resource management professionals surveyed by the committee expressed a need for more narrowly defined occupations; the lack of greater detail discourages this community from using O*NET (see Chapter 7).

This chapter describes the evolution of both the O*NET and the SOC systems. It then discusses how users view and use the occupational titles in the current O*NET classification system that do not completely correspond to those in the SOC.

THE O*NET OCCUPATIONAL CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

O*NET-SOC 2000

The first O*NET database, published in 1998, included 1,122 “occupational units.” The following year, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) (1999) mandated that all federal agencies collecting occupational data use the SOC system (see Box 3-1). In response to the OMB mandate, the O*NET classification system was revised, becoming O*NET-SOC 2000 (Levine et al., 2001).

O*NET-SOC 2006

Between 2000 and 2006, further development resulted in O*NET-SOC 2006, to advance two stated goals. The first goal was to increase correspondence between O*NET and the SOC, in order to (a) improve the efficiency and accuracy of data collection (by allowing improved targeting of job incumbents for sampling) and (b) assist users in linking O*NET data to other SOC-based data sources. The second goal was to identify new and emerging occupations in order to (a) reflect changes in technology and society, (b) serve workforce investment in high-growth industry sectors, and (c) meet user needs (National Center for O*NET Development, 2006a).

Advancing the first goal, O*NET-SOC 2006 reduced the total number of occupations from 1,165 to 949 and the number of occupations not corresponding to the SOC to 128. To achieve the second goal, the National

Center for O*NET Development announced that research to identify new and emerging occupations was ongoing and would be incorporated in future revisions of the classification system.

To identify new and emerging occupations, the O*NET Center developed a methodology that includes soliciting information from O*NET users about occupations, gathering and analyzing data on proposed new occupations from a variety of sources, and requesting final approval from the Employment and Training Administration to begin gathering data related to these occupations (National Center for O*NET Development, 2006a).

O*NET-SOC 2009

The current O*NET database (14.0) incorporates a new classification system, O*NET-SOC 2009, which incorporates more new and emerging occupations. This revision was developed to advance the following goals (National Center for O*NET Development, 2009, p. 13):

-

Meet the demand for more extensive information for workforce investment activities within rapidly changing in-demand industry clusters;

-

More accurately reflect the many occupations found in today’s world of work through the inclusion of new and emerging occupations;

-

Maintain efficient and precise sampling of occupations for data collection through the use of SOC-based occupational employment statistics produced by BLS and the states; and

-

Maintain correspondence of O*NET data with employment projections and other labor market information.

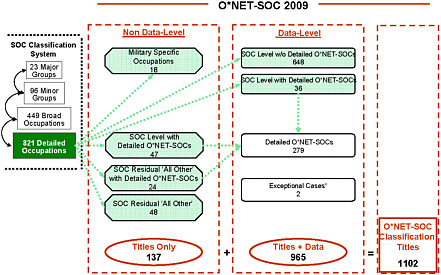

O*NET-SOC 2009 includes 1,102 occupations, of which data are collected on 965. Based on research begun in 2006, the system includes 153 new and emerging occupations identified in 17 “in-demand industry clusters” (as defined by the Department of Labor). Although a few of these additional occupations are identical to new occupations included in SOC 2010 (see Box 3-1), most are “breakouts” of existing SOC occupations or of SOC residual categories (e.g., “managers, all other”). These new occupations are created by splitting an SOC occupation and adding additional digits, beyond the six digits at the most detailed level of the SOC system. For example, in the field of health care, O*NET-SOC 2009 includes 37 occupations that are breakouts of SOC occupations (Lewis and Rivkin, 2009).

|

BOX 3-1 The Standard Occupational Classification System Currently, federal statistical agencies collecting occupational data are required to use occupational classification systems that are aligned with the 1999 SOC (Office of Management and Budget, 1999). The 1999 SOC includes 4 levels, with 23 major groups at the highest level and 821 specific occupations at the lowest level. Each specific occupation is designated by a six-digit code. In addition to directing all federal statistical agencies to align with the SOC, the Office of Management and Budget (1999) stated that agencies may create more specific occupational categories, if desired: In addition, data collection agencies wanting more detail to measure additional worker characteristics can split a defined occupation into more detailed occupations by adding a decimal point and more digits to the SOC code. For example, Secondary School Teachers, Except Special and Vocational Education (25-2031) is a detailed occupation. Agencies wishing to collect more particular information on teachers by subject matter might use 25-2031.1 for secondary school science teachers or 25-2031.12 for secondary school biology teachers. Beginning in fiscal year 2010, all federal agencies collecting occupational data will be required to align their occupational classification systems with the revised and updated SOC, known as SOC 2010 (Office of Management and Budget, 2009). It continues the 23 major groups from SOC 1999 and adds new occupations, for a total of 840 detailed occupations. Occupational areas with significant revisions and additions include information technology, health care, printing, and human resources. Agencies will continue to be permitted to split a defined occupation by adding a decimal point and more digits to the SOC code. Dixie Sommers, a member of the interagency SOC policy commit |

Inclusion of Occupations for Which Data Are Not Collected

The current O*NET database maintains and displays for users the names and codes of 137 SOC occupations for which O*NET data are not collected (see Figure 3-1). Most of these occupations are included to maintain alignment with the SOC and ensure that O*NET users can readily access data on workforce characteristics—one of the six major windows in the O*NET content map (see Figure 1-1). For example, the inclusion of the SOC occupation “nuclear technicians” (19-4051) allows users to find information on education levels, wages, and projected employment

|

tee that oversaw the development of SOC 2010, provided information about the process to the panel (Sommers, 2009). In revising and updating the SOC, the policy committee used a list of detailed criteria, including the following criterion related to collectability of data: The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and the U.S. Census Bureau are charged with collecting and reporting data on total U.S. employment across the full spectrum of SOC major groups. Thus, for a detailed occupation to be included in the SOC, either the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the Census Bureau must be able to collect and report data on that occupation. Sommers (2009) reported that DOL and the National Center for O*NET Development contributed to the revision of the SOC in several ways. First, the Employment and Training Administration (ETA) is represented on the policy committee by the O*NET team leader, who shared knowledge the O*NET Center staff has gained through collection of data on knowledge, skills, tasks, and other detailed characteristics of jobs. Second, ETA and the O*NET Center contributed specific suggestions for additional detailed occupations to include in SOC, based on their experience in collecting occupational data and on their research into new and emerging occupations. The SOC policy committee reviewed the suggested additional occupations in light of both its criteria and public comments in response to the Federal Register notices. The end result is that the 2010 SOC will include 10 new occupations that are currently in O*NET-SOC 2009 at a level of detail below the 2000 SOC, or are similar to O*NET-SOC 2006 occupations that are disaggregated from SOC occupations. However, the SOC policy committee determined that many more of the new occupations proposed by DOL and the O*NET Center did not meet the collectability principle noted above. |

for this occupation. This information is obtained from federal and state agencies that collect wage and employment data using the SOC. However, because the O*NET Center does not collect O*NET information for the “nuclear technicians” occupation, the database does not provide more detailed information on this occupation’s Skills, Abilities, Generalized Work Activities, and other characteristics of this occupation. The database does provide information collected by the O*NET Center on the Skills, Abilities, and other characteristics of two breakouts of the “nuclear technicians” occupation—“nuclear equipment operation technicians” (19-4051.01) and “nuclear monitoring technicians” (19-4051.02).

FIGURE 3-1 The O*NET-SOC 2009 occupational classification system.

SOURCE: National Center for O*NET Development (2009). Reprinted with permission.

In addition to maintaining SOC occupations and SOC residual occupations (e.g., “agricultural workers, all others”) in the classification system, O*NET-SOC 2009 maintains military occupations. No data are collected on these occupations, however, because the O*NET Center and DOL determined that the military services would be the best source of this information (Lewis, Russos, and Frugoli, 2001).

USER VIEWS OF MORE DETAILED OCCUPATIONAL INFORMATION

O*NET-SOC 2009 includes 279 detailed breakouts of SOC occupations, or about 25 percent of 1,102 occupations in the system. In comparison, O*NET-SOC 2006 included 126 breakouts of SOC occupations, or about 13 percent of 949 occupations in the system (National Center for O*NET Development, 2006a). Given this large increase in the proportion of breakouts, it is important to consider how O*NET users currently view and use these more disaggregated occupational data.

For example, O*NET-SOC 2006 breaks the SOC occupation “accountants and auditors” (13-2011) into “accountants” (13-2011.01) and “auditors” (13.2011.02). These more detailed occupations can be linked to the SOC through the extended digits they are assigned. BLS gathers data on

current average wage level and current employment levels and prepares projections of future employment using the SOC system. It is therefore possible to obtain all of these types of data for the combined SOC, “accountants and auditors,” but none of these labor market data are available for the separate O*NET occupations of “accountant” and “auditor.”

The views of different O*NET users about the value of breakouts vary with the purposes for which they are using the system. For example, job analysts consulting with businesses and government agencies often use O*NET data as a starting point for defining tasks, knowledge, skill, ability, and other attributes required by the job and supplement this with additional information on the particular job context or job. For these users, information at the SOC level often provides an adequate starting point, but they would probably welcome the more detailed information from a breakout (e.g., information about an auditor, rather than about accountants and auditors). Because job analysts typically focus on defining the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other attributes of the job, they may have no need for information on wages, employment levels, or other information gathered at the SOC level. If job analysts do need these types of data, they may obtain it from private industry surveys, web-based job posting systems, or other sources.

The career development community welcomes the O*NET Center’s research on new and emerging occupations and values the more detailed information provided by breakouts (see Chapter 6). For example, a guidance counselor would prefer to provide a young person with information about the educational, experience, and other requirements to become an auditor than about the broader group of auditors and accountants (Janis, 2009). A few respondents to the committee’s informal survey of the career development community requested that O*NET include information on more and newer occupations (Janis, 2009).

At the same time, however, the inclusion of breakouts in O*NET poses some challenges to career information delivery systems. Developers of these systems use O*NET extensively, downloading the entire database, revising the information to make it more user-friendly, and linking it to other data sets, including BLS data on wages and employment levels in occupations. Because these system developers highly value wage and employment information collected by the states and BLS, some of them currently work around the breakouts in O*NET. For example, the Georgia Career Information System creates a combined occupational description using information from the separate O*NET-SOC 2006 occupations “accountants” and “auditors” to essentially recreate the SOC occupation “accountants and auditors.” The combined information is then linked to federal and state information on wages, current employment levels, and projected future employment in the “accountants and auditors” occupation.

In general, in the field of career development, the importance of linking O*NET occupational information (such as the level of Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities required for an occupation) with wage data depends on the age of the user. Guidance counselors working with younger people have less need of detailed wage data than guidance or job placement counselors working with adult workers. For example, a middle school guidance counselor could meet students’ needs with information from O*NET about the requirements of the “accountant” and of the “auditor,” along with information from the BLS about wages and projected demand for the broader SOC occupation “accountants and auditors.” However, adult workers with greater financial responsibilities have greater need for specific wage data. A career counselor or job placement specialist assisting an unemployed adult worker and working with O*NET information about the requirements of the “accountant” or the “auditor” would not be able to provide information about wage levels in the two breakout occupations. Of course, the counselor or the workers might be able to obtain more localized information about the wages in these two occupations from other sources, such as online job postings.

State and local labor market information specialists in public workforce development offices very frequently link O*NET data to SOC data. They do so both to assist individual job seekers and also to analyze and understand broader workforce trends. For example, some analysts have linked the two types of data to project future skill demands in their states or metropolitan regions; such projections help education and training providers align curriculum with skills in demand. Because they view the value of O*NET data primarily in terms of their ability to be linked to wage, employment, and other data collected at the SOC level, state labor market information specialists suggest that the occupational definitions in the two systems be coordinated (Ewald, 2009). Some state labor market information specialists have requested that, in the future, the O*NET Center continue its current policy of categorizing all new occupations as breakouts of SOC occupations and including additional digits beyond the six digits of the related SOC occupation (Calig and Ewald, 2009).

Nevertheless, some state and local workforce development officials value the greater detail provided by breakouts of SOC occupations in the O*NET classification system. For example, one survey respondent indicated that developers of a statewide job information system would like O*NET to include more information on newer occupations, including “green” occupations—and occupations in health care, construction, and energy (Janis, 2009). In addition, state labor market information specialists, in a letter to the Office of Management and Budget, requested that O*NET provide more detailed occupational titles in the fields of information technology and green jobs (Reamer et al., 2009).

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The question of the level at which occupations should be defined and described is not new. The National Research Council study of the Dictionary of Occupational Titles stated, “Research priority should be given to developing criteria for defining occupations—the aggregation problem” (National Research Council, 1980, p. 15).

There is a tension between the need of some O*NET users for more aggregated occupational categories and the need of other users for more disaggregated occupational categories. For the workforce development and career development communities, much of the power of O*NET derives from the alignment of its occupational classification system with the occupations included in the SOC system. For the human resource management community, the occupations in O*NET often lack the specificity needed for its purposes. To the degree that an O*NET occupation represents an aggregation of very different individual jobs or job titles, it will lack precision and usefulness to human resource managers as a unit of analysis and description. Moreover, from a statistical standpoint, data that are collected from a diverse set of component jobs and then combined or averaged when creating the occupation-level data reported in O*NET may be misleading or cannot be interpreted. These problems cause significant dissatisfaction with O*NET data among human resource managers, and, in many cases, discourage their use.

Reflecting this tension between the needs of different O*NET users, the panel did not agree about the appropriate level of aggregation of the occupational categories used in O*NET. Some supported the 2009 addition of new and emerging occupations and favored continuing expansion of the number of occupations, while others thought that a smaller number of more highly aggregated occupations, as defined by the SOC, should be included in O*NET.

Recommendation: The Department of Labor, with guidance from the technical advisory board recommended in Chapter 2 and the user advisory board recommended in Chapter 6, should conduct an assessment of the potential benefits of continuing to expand the O*NET occupational classification system to include occupational titles more specific than those in the SOC. It should also consider all potential costs of continued expansion, including but not limited to the costs of collecting data on a larger number of occupations and of collecting data on occupations that may not easily be linked to labor market information collected at the SOC level.

If this assessment determines that the classification system should continue to expand, the research organization should

-

Conduct research to develop a systematic procedure and set of decision rules suitable for guiding ongoing disaggregation efforts and defining new occupations. This should include analysis of alternative methods for defining new occupations, such as the current methods used by the National Center for O*NET Development and methods used in the Current Population Survey and the SOC system. It should also include development of methods to determine when within-occupation aggregation obscures significant variability in physical and other requirements.

-

Develop methods to maintain, and regularly update crosswalks and linkages between the new occupations and SOC occupations.

REFERENCES

Advisory Panel for the Dictionary of Occupational Titles. (1993). The new DOT: A database of occupational titles for the twenty-first century (final report). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration.

Calig, J., and Ewald, K. (2009). O*NET and workforce development: Assessing opportunities. Paper prepared for the Panel to Review the Occupational Information Network (O*NET). Available: http://www7.nationalacademies.org/cfe/Ewald%20and%20Calig%20paper.pdf [accessed June 2009].

Ewald, K. (2009). O*NET and workforce development: Assessing opportunities. Presentation to the Panel to Review the Occupational Information Network (O*NET). Available: http://www7.nationalacademies.org/cfe/Ewald%20Power%20point.pdf [accessed June 2009].

Janis, L. (2009). Summary of responses to Les Janis survey on use of O*NET in career development. Available: http://www7.nationalacademies.org/cfe/Janis%20Survey%20Summary%20Responses.pdf [accessed June 2009].

Karman, S. (2009). Definition of disability: What compels SSA to use DOT. Presentation to the Panel to Review the Occupational Information Network (O*NET), March 26. Available: http://www7.nationalacademies.org/cfe/Karman%20Power%20point.pdf [accessed June 2009].

Levine, J., Nottingham, J., Paige, B., and Lewis, P. (2001). Transitioning O*NET to the Standard Occupational Classification. Available: http://www.onetcenter.org/reports/TRreport_xwk.html [accessed June 2009].

Lewis, P., and Rivkin, D. (2009). O*NET program briefing. Presentation to the Panel to Review the Occupational Information Network (O*NET). Available: http://www7.nationalacademies.org/cfe/Rivkin%20and%20Lewis%20ONET%20Center%20presentation.pdf [accessed November 2009].

Lewis, P., Russos, H., and Frugoli, P. (2001). O*NET occupational listings, database 3.0. Available: http://www.onetcenter.org/dl_files/3_1Intro.pdf [accessed July 2009].

National Center for O*NET Development. (2006a). Updating the O*NET-SOC taxonomy. Raleigh, NC: Author. Available: http://www.onetcenter.org/dl_files/UpdatingTaxonomy_Summary.pdf [accessed June 2009].

National Center for O*NET Development. (2006b). New and emerging occupations methodology development report. Available: http://www.onetcenter.org/reports/NewEmerging.html [accessed June 2009].

National Center for O*NET Development. (2009). New and emerging occupations of the 21st century: Updating the O*NET-SOC taxonomy. Available: http://www.onetcenter.org/reports/UpdatingTaxonomy2009.html [accessed July 2009].

National Research Council. (1980). Work, jobs, andoccupations: A critical review of the Dictionary of Occupational Titles. A.R. Miller, D.J. Treiman, P.S. Cain, and P.A. Roos (Eds.). Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Available: http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=92 [accessed May 2009].

Office of Management and Budget. (1999). SOC Federal Register notice. Available: http://www.bls.gov/soc/soc_sept.htm [accessed June 2009].

Office of Management and Budget. (2009). 2010 Standard Occupational Classification (SOC): Final decisions: Notice. Federal Register, 74(12), 3920-3936. Available: http://www.bls.gov/soc/soc2010final.pdf [accessed May 2009].

Reamer, A., Carnevale, C., Nyegaard, K.D., Judy, R., Poole, K., Alssid, J., Stevens, D., Reedy, E.J., Dorrer, J., and Weeks, G. (2009). Comments in response to ETA proposed O*NET data collection program. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution. Available: http://www7.nationalacademies.org/cfe/Andrew%20Reamer%20Comments%20on%20ONET.pdf [accessed November 2009].

Sommers, D. (2009). O*NET and the Standard Occupational Classification. Statement before the Panel to Review the Occupational Information Network (O*NET). March 26. Available: http://www7.nationalacademies.org/cfe/Sommers.ONET%20Panel%20Statement.pdf [accessed July 2009].

U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration. (2008). O*NET data collection program, Office of Management and Budget clearance package supporting statement, Volume 1. Raleigh, NC: Author. Available: http://www.onetcenter.org/dl_files/omb2008/Supporting_Statement2.pdf [accessed June 2009].