5

Reducing the Burden of Cardiovascular Disease: Intervention Approaches

The preceding chapters have described the many interrelated risk factors that influence cardiovascular health, which involve aspects of economies and societies that extend far beyond public health and health systems. This underscores the complexity of any undertaking to promote cardiovascular health and to prevent and manage cardiovascular disease (CVD). In addition to being complex, CVD is also a long-term problem. It cannot be addressed through a singular, time-limited commitment but rather requires long-term interventions and sustainable solutions.

This chapter first outlines the ideal vision of a comprehensive approach to promote cardiovascular health and reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease. The chapter then turns to a more pragmatic and focused discussion, starting first with a description of the committee’s approach to the evidence. This is followed by a more thorough consideration of the rationale and evidence for components of the ideal approach, which include population-based approaches such as policies and communications campaigns; delivery of health care; and community-based programs. Recognizing the complexity of the disease and the local realities and practical constraints that exist in developing countries, the goal of this final section of the chapter is to identify, based on the totality of the available evidence, what is most advisable and feasible in the short term and what might hold promise as part of longer-term strategies.

IDEAL STRATEGY TO ADDRESS GLOBAL CVD IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD

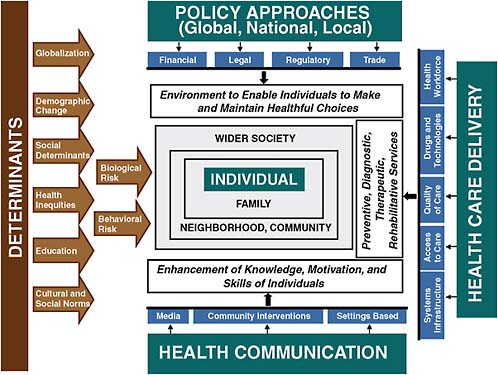

The factors described in Chapters 2 and 3 that contribute to the burden of CVD and related chronic diseases are the targets for change in the quest to promote global cardiovascular health. These can be divided into behavioral factors (such as tobacco use, diet, and physical activity); biological factors (such as blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood glucose); psychosocial factors (such as depression, anxiety, acute and chronic life stressors, and lack of social support); health systems factors (such as access to care, screening, diagnosis, and quality of care); and intersectoral factors (such as tobacco control policies and agricultural policies). The evidence describing the interrelated determinants of CVD provides a strong conceptual basis for a strategy that coordinates across multiple sectors and integrates health promotion, prevention, and disease management as part of a long-term, comprehensive approach. This approach would employ multiple intervention strategies in a mix of programs and policies that accomodate variations in need according to context and locale.

The ideal approach would take advantage of opportunities for intervention at all stages of the life course in order to promote cardiovascular health by preventing acquisition and augmentation of risk, detecting and reducing risk, managing CVD events, and preventing the progression of disease and recurrence of CVD events. Policies and programs to change the factors that contribute to CVD would be designed to work through population-wide approaches; through interventions within health systems; and through community-based programs with components in schools, worksites, and other community settings. A comprehensive strategy of this kind that takes into account the full range of complex determinants of CVD, illustrated in Figure 5.1, would have the theoretical potential to produce a synergistic interaction among approaches at individual and population levels. Concurrent modalities could include policy and regulatory changes, health promotion campaigns, innovative applications of communications technologies, efficient use of medical therapies and technologies, and integrated clinical programs. For individuals already at high risk or with existing disease, this approach would combine education, support, and incentives to both address behavioral risk factors and improve adherence to clinical interventions. Participation in this approach extends beyond clinical providers and public health approaches to also include public media outlets, community leaders, and related sectors, especially food and agriculture policy, transportation and urban planning, and private-sector entities such as the food and pharmaceutical industries. All these players are potential partners both in assessing needs and capacity and in developing and implementing solutions.

Such a comprehensive approach stands as an ideal for countries facing the burden of CVD and for global stakeholders in the fight against CVD and related chronic diseases. Reality, of course, complicates this ideal considerably. A comprehensive integrated approach of this kind has not been successfully implemented in a model that can be readily replicated in low and middle income country settings. Progress in high income countries points to models for many of the components that could make up such an ideal approach to CVD, but interventions that may be efficacious in certain settings cannot be assumed to be effective if they are implemented in settings that have significantly different available resources and differ significantly at the level of policy or population characteristics. Most of the intervention components described as part of the ideal approach do not have sufficient evidence to support scale-up for widespread implementation in low and middle income countries in the immediate term. Even with sufficient evidence to support implementation, many low and middle income country governments might not have adequate resources in place to undertake ambitious, comprehensive, full-scale approaches.

Nevertheless, although the components are likely to work best in synergy with each other, the lack of readiness and capacity to accomplish the comprehensive ideal is not reason to do nothing. An impact on the very high burden of CVD is possible even without doing everything that makes up the ideal. Indeed, developing countries will want to focus more pragmatically on efforts that promise to be economically feasible, have the highest likelihood of intervention success, and have the largest morbidity impact. The goal of this chapter is to provide an analysis to help determine (1) what policies, programs, and clinical interventions have sufficient evidence for priority implementation in developing countries in the near term and (2) what approaches have a solid conceptual basis but require greater knowledge based on specific policies and programs with demonstrated effectiveness and implementability in developing-country settings in order to make progress toward implementation in the medium and long term. Chapter 7 will continue the discussion of feasibility and prioritizing the use of limited resources in low and middle income countries with a synthesis of the available economic evidence and future economic research needs for the intervention approaches described in this chapter.

Building a Strategy to Address CVD

The following briefly outlines the series of components needed for countries and supporting global stakeholders to build a strategy to promote cardiovascular health. As described above, these components would ideally be integrated to work toward a comprehensive intervention strategy. The intent is to develop a supportive policy environment and build the capac-

ity to develop, implement, and evaluate intervention programs, with the ultimate goal of reducing the burden of CVD through reduction of risk factors and management of disease. This includes “top-down” policies and complementary “bottom-up” approaches in health care delivery systems and in community-based education and health promotion programs. The specific components within each of these steps and examples of the available evidence to support their implementation are described later in the chapter, along with more discussion of the limitations, taking into account gaps in the evidence and variations among countries in baseline capacity, economic status, and level of infrastructure.

Needs and Capacity Assessment

A crucial basis for developing policies and programs is for governments and communities to estimate and, where possible, measure the nature of the problem as it occurs in the local context where approaches will be implemented; to assess the needs of the population; to catalog current efforts; to assess the available capacity and infrastructure to address CVD and related chronic diseases; and to gauge the political will to support the available opportunities for action. This assessment will inform priorities and determine choices about the implementation of evidence-based policies and programs as well as capacity-building efforts. This should lead to specific and realistic goals for intervention strategies that are adapted to local baseline capacity and burden of disease and that also aim to improve that baseline capacity. This critical underlying step was discussed in full in Chapter 4.

Country-level measurement, assessment, and prioritization of this kind can occur at the level of national or local governments, such as provincial or city-level health authorities. In many low and middle income countries, this will require the development of sufficient capacity and infrastructure to carry out population-based approaches for measuring cause-specific mortality and behavioral and biological risk factors. In countries with very limited capacity at baseline, at first it may be nongovernmental organizations, foreign assistance agencies, and other donors who need to carry out a needs assessment and prioritization before implementing programmatic efforts. Regardless of the driving force behind the initiated action, this strategic planning can, to the extent possible, involve local authorities, be harmonized with local efforts, and be designed as an opportunity to improve local baseline capacity over time.

Policy Strategies

When a baseline is established and priorities are determined based on country-level data, the starting place for developing intervention ap-

proaches is policy strategies for population-based prevention. The primary population approach can be based on setting or changing policies, incentives, and regulations, especially those related to food, agriculture, and tobacco. There is evidence to support the implementation of some of these policies in the immediate term. For those developing countries where there exist democratic means to develop policies, where regulatory and enforcement capacity is sufficient, these policy changes may include, for example, taxation and regulations on tobacco production and sales; regulations on tobacco and food marketing and labeling; alterations in subsidies for foods and other food and agricultural policies; and strategies to make rapid urbanization more conducive to health. Regulatory change usually needs to be incremental and should be proportional to the possible impact and cost.

Health Communications

Both in coordination with policy changes and as a separate strategy for affecting crucial CVD-related behaviors, there is substantial promise in implementing health communications and education efforts. Public communication interventions that are coordinated with select policy changes can enhance the effectiveness of both approaches, which together can help create an environment in which more targeted programs in health systems and communities can succeed. Even in the absence of an ideal policy environment, well-constructed stand-alone population-level health communication efforts have the potential to be effective in encouraging population behavior change, for example, in areas such as smoking initiation and salt and fat consumption. Depending on the governmental infrastructure within a country, policies with coordinated communication and health education efforts can occur at the level of national or local authorities.

Delivery of Quality Health Care

Along with select population-based approaches, a key step in addressing CVD is to strengthen health systems to deliver high-quality, responsive care for the prevention and management of CVD. Improving health care delivery includes, for example, provider-level strategies, financing, integration of care, workforce development, and access to essential medical products. The need to strengthen health systems in low and middle income countries is not specific to CVD, and it is important that ongoing efforts in this area take into account not only traditional focus areas such as infectious disease and maternal and child health but also CVD and related chronic diseases as well as chronic care needs that are shared among chronic non-infectious diseases and chronic infections such as HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis (TB).

Community-Based Programs

Along with efforts to implement population-based approaches and to strengthen health systems, an ideal comprehensive integrated approach would also include community-based programs that offer opportunities to access individuals where they already gather, such as schools, worksites, and other community organizations. Depending on local priorities, there is potential for synergism in both effectiveness and economic feasibility through coordinated interventions that target multiple risk factors, are conducted in multiple settings in communities, and coordinate the health systems and population-based strategies described above with related, community-specific strategies. Because of the lack of community-based models that have been successfully implemented, evaluated, and sustained in low and middle income country settings, the critical next step in these settings is to support research to develop and evaluate demonstration projects through implementation trials. In many cases, the focus can be on adapting and evaluating programs with demonstrated success in developed countries. The design of demonstration programs will need to take into account local infrastructure and capacity to develop and maintain such programs over time, particularly if they are ultimately intended to affect a large portion of the population and operate on a large scale.

Scale-Up and Dissemination

The ultimate goal when intervention approaches in all these domains are demonstrated to be effective and feasible is scale-up, maintenance, and dissemination. In addition to implementing best practices and evidence-based policies and programs on a larger scale, this includes disseminating in a broader global context, by sharing knowledge among similar countries with analogous epidemiological characteristics, capacity, and cultural norms and expectations.

Ongoing Monitoring, Evaluation, and Assessment

As described in Chapter 4, ongoing surveillance and evaluation of implemented strategies will allow policy makers and other stakeholders to determine if implemented actions are having the intended effect and meeting the defined goals, and to reassess needs, capacity, and priorities over time. This will be critical to alter policies and programs as priorities change, as new lessons are learned, and as a country goes through inevitable transitions in its economy and its health or social environments.

Global Support

As described in more detail in Chapter 8, international agencies can play an important role in working toward comprehensive country-level approaches. These agencies can help initiate and enrich any country’s CVD prevention and management process through direct financial and technical assistance. In addition, external aid and coordination can facilitate the transfer of lessons learned among countries, allowing each country to actively contribute to the international repertoire of prevention strategies.

APPROACH TO THE EVIDENCE

This chapter is concerned with what works. The challenge is to define what qualifies as an intervention that works, to martial these findings together to establish a coherent evidence base, and then to use this as the basis to necessarily prioritize approaches. This section of the chapter briefly discusses the committee’s approach to considering evidence for evaluating intervention approaches for CVD at all levels. This includes how the methodology for evaluating large-scale programs and population-based and policy interventions differs from clinical interventions and small-scale projects as well as a special emphasis on the importance of effectiveness and implementation evidence in relevant contexts.

The attempt to define a broad-based set of effective approaches available for CVD promotion and prevention rests on data standards—notably data standards that continue to evolve. The aspirational standard is evidence that describes causal linkages between intervention and better health status (i.e., outcomes). These data should meet the additional standards of contextual generalizability so that the reported findings are feasible based on implementation evidence and economic evaluation and adaptable in a variety of settings.

The intent is that good epidemiologic observational data on the role of risk factors and the preventive effects of reductions in those risk factors will lead to hypotheses about causal pathways that interventions are designed to influence. Ideally, these hypotheses will be confirmed by prospective interventional studies that are repeated and reaffirmed in a variety of settings. Evidence from randomized trials can be highly valuable to infer causality. As a rigid evidence standard, however, this is not always available, feasible, necessary, or even optimal. For many intervention approaches, the best available evidence can also come from, for example, cohort evaluations and qualitative assessments as well as other research methodologies that support plausible causal linkages. For policy and public health approaches in particular, traditionally defined rigorous evaluation standards are often unrealistic, and it is instead a comprehensive perspective on the totality of

the available evidence that is weighed alongside other policy pressures to drive implementation decisions. Therefore, the committee did not apply randomization as a standard of evidence for consideration of the illustrative examples included in this chapter. However, the committee did restrict its review of the evidence to published studies that included some comparison condition, either through a control group or a comparison to before and after an intervention was implemented.

The second standard for evidence set out by the committee is one of relevancy, an issue of particular importance here, although it is by no means exclusive to low and middle income countries. Conceptually, the ideal is not narrowly defined evaluations focused on internal validity but instead evaluations that look beyond efficacy—the estimation of what is possible—to effectiveness—the determination of what actually was accomplished by an intervention in a real-world setting. This refers to what is often a tension between confident findings of causal influence and confident findings of the relevance of evidence. Studies imposing enough controls on the context to support strong causal statements often in the process have to create a context that is distant from the messy environment and constraints in which programs at scale will be implemented, particularly in low and middle income countries. This review of evidence by the committee respects that tension, and then puts substantial emphasis on relevance.

Beyond effectiveness and relevance, the ultimate ideal standard to inform large investments in programs and intervention approaches is evidence from implementation research, operations research, and health services research. In addition, evidence on economic feasibility is a critical factor in determining implementation readiness and prioritizing intervention approaches. The available evidence from economic evaluations of intervention approaches is the subject of Chapter 7.

Applying the standards described here to the available evidence for CVD in developing countries revealed significant gaps in the evidence base, especially given the desire to have a concrete basis for advocating policy change, system change, or program implementation. The committee, however, does not intend that the message about higher data mandates with a responsible exposure of these data gaps be equated with a suggestion of inaction. A principle throughout the report is one of being action-oriented based on available findings. The committee’s review of the available evidence according to these standards informed an analysis of which potential components of the ideal comprehensive approach warrant priority for implementation or, if near-term implementation is not supported, which components warrant other intermediate steps to develop the evidence base in support of implementation in the longer-term.

Given the broad and global scope of this study, a comprehensive systematic review of all available evidence related to every aspect of CVD and

related chronic diseases was not within the scope of this project. Nor was it feasible for this report to catalog every intervention approach that has been attempted and documented across all countries. Instead, to present the rationale put forth by the committee, the following sections include illustrative examples that represent the best available evidence to support the committee’s findings on the implementation potential for component strategies. In order to limit the length of this document and to avoid replication of existing work, the committee sought existing relevant, high-quality, systematic and narrative reviews. In content areas where these were available, this chapter includes summaries of key findings, but otherwise refers the reader to the available resources for more detailed information.

The focus is on intervention approaches for CVD with evidence for effectiveness and implementation in developing countries. Where this evidence is limited, generalizable examples are offered with evidence for effectiveness and implementation from both CVD-specific approaches in developed countries and developing-country evidence for non-CVD health outcomes. An assessment of the transferability of the evidence for these approaches is included. For components where there is limited or no effectiveness or implementation data, the logical basis for intervention approaches is discussed as being derived from knowledge about the determinants of CVD, modifiable risk factors, and characteristics of ideal intervention design and implementation.

Conclusion 5.1: Context matters for the planning and implementation of approaches to prevent and manage CVD, and it also influences the effectiveness of these approaches. While there are common needs and priorities across various settings, each site has its own specific needs that require evaluation. Additional knowledge needs to be generated not only about effective interventions but also about how to implement these interventions in settings where resources of all types are scarce; where priorities remain fixed on other health and development agendas; and where there might be cultural and other variations that affect the effectiveness of intervention approaches. Translational and implementation research will be particularly critical to develop and evaluate interventions in the settings in which they are intended to be implemented.

COMPONENTS OF A STRATEGY TO REDUCE THE BURDEN OF CVD

This section presents in more detail the rationale for the ideal approach described previously and the evidence for the main components, which include population-based approaches such as policies and health

communications campaigns; delivery of health care; and community-based programs. Recognizing the complexity of the disease and the local realities and practical constraints that exist in developing countries, the goal of this final section of the chapter is to identify, based on the totality of the available evidence, policies, programs, and strategies to improve clinical care that have sufficient evidence for advisable and feasible implementation in developing countries in the near term as well as approaches that have a solid conceptual basis but need more evidence for specific policies and programs with demonstrated effectiveness and implementability in developing country settings to progress toward implementation in the medium and long term.

Intersectoral Policy Approaches1

Chapter 2 described the complexity of the determinants of CVD, which are drawn from a range of broad social and environmental influences. As a result, many of the crucial actions that are needed to support the reduction of CVD burden are not under the direct control of health ministries, but rather include other governmental agencies as well as private-sector entities. For example, they rely on tax rates on tobacco set by economic agencies, food subsidy policies set at agricultural agencies, access rules for public service advertising set by communication agencies, curricular choices by education agencies, and commitments to product reformulation by multinational corporations. Thus, success in achieving the specific priority goals for CVD programs will rely heavily on decisions made outside of health agencies, and that success will only come if there is substantial intersectoral collaboration.

The specifics of how that collaboration will come about will vary with the particular political arrangements in a country, but there will be a common theme: success will depend on building a shared commitment across sectors in the whole of government. This will require engaging not only those already motivated by health-related goals but also those who have very different pressures and considerations driving their decision making. Therefore, it is important to acknowledge the different forces that drive policy decisions in different sectors in order to seek out shared objectives, including economic objectives. To this end, there will be a need not only to make a case that the population as a whole will benefit from addressing CVD, but also to make the specific case that work to target CVD-related behaviors and outcomes will be in the interest of each collaborating agency or stakeholder in the private sector. For example, it may not be enough to

talk up health benefits to encourage increased taxation on tobacco; evidence bearing on the likely gains and losses in revenues associated with such increased taxation and reduced tobacco consumption may have higher priority. To this end, a pragmatic approach will require a realistic assessment of what the fundamental requirements are for CVD-related needs, and what aspects of a proposed policy might be negotiable.

Intersectoral policy approaches for CVD will not be simple to implement, and a central part of intervention will be to form a strategy to stimulate such actions. In addition, just as with all interventions, policies need to be context specific and culturally relevant, and need to take into account infrastructure capacity and economic realities. A review commissioned for this committee identified the key success factors for implementing intersectoral approaches (Jean and St-Pierre, 2009). These include elements related to context, including political will and support; a favorable legislative, economic and organizational environment; and community support. There also needs to be a well-defined problem targeting an issue that is widely significant with a clear rationale for intersectoral action. Planning is also an important aspect of intersectoral approaches and requires credible organizers, as well as carefully chosen partners with a shared vision, clearly defined roles and responsibilities, and sufficient authority. It is also crucial to have evaluation based on concrete and measurable objectives. The final key success factor is a system for adequate communication, flexible and adaptable decision making, and conflict resolution.

The following sections present a more detailed discussion of the policy levers that have the most potential to affect the future course of CVD within an intersectoral approach by addressing specific goals, including tobacco control, reduced consumption of salt and unhealthful food, and increased physical activity. The rationale for these policy approaches are described, along with precedent for implementation. The focus is on examples from low and middle income countries when possible. Evaluations of policy interventions are not common, especially in low and middle income country settings, but where an evaluation has generated evidence on policy this is presented as well.

Tobacco Control Policies

Tobacco control, including efforts to reduce both tobacco use and exposure to secondhand smoke, is one of the most well-developed areas of CVD-related policy. Strategies for tobacco control in high income countries have been reviewed extensively elsewhere and will not be repeated here (Breslow and Johnson, 1993; Frieden and Bloomberg, 2007; IOM, 2010; Jha et al., 2006). This precedent in high income countries provides a strong

rationale for policy measures of this type in low and middle countries with adequate regulatory and enforcement capacity.

Indeed, strategies for tobacco control worldwide were laid out exhaustively as part of the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) (WHO, 2008b). The FCTC emphasizes the importance of both demand reduction and supply control strategies, including taxation measures on tobacco products, protection from exposure to tobacco smoke, packaging and labeling of tobacco products to include health warnings and to ban misleading terms like “light” and “mild,” education and public awareness campaigns, controls on tobacco advertising, tobacco cessation services, control of illicit trade in tobacco products, control of sales to minors, and provision of support for economically viable alternative economic activities. WHO has also presented a policy package for tobacco control to support implementation of the FCTC (WHO, 2008b). Known as the MPOWER package, the focus is on six key policy areas: monitor tobacco use, protect people from tobacco smoke, offer help to quit tobacco use, warn about the dangers of tobacco, enforce bans on tobacco advertising and promotion, and raise taxes on tobacco products.

However, although many low and middle income countries have signed the FCTC treaty, implementation has been achieved in only a limited number (Bump et al., 2009). Indeed, there are only a few well-documented examples of implementation of tobacco control policies in low and middle income countries to serve as models, including Bangladesh, Brazil, Poland, Thailand, and South Africa (de Beyer and Brigden, 2003). Therefore, evaluation strategies are needed to examine the effects of tobacco control policies in low and middle income settings, and there is a need for more knowledge and analysis of the barriers to successful implementation and how to overcome them (Bump et al., 2009).

In Bangladesh, systematic and concerted efforts by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) provide a model of very low-budget advocacy (Efroymson and Ahmed, 2003). Similarly, in Thailand tobacco control policy has been significantly influenced by NGOs in the health sector with direct access to government officials (Vateesatokit, 2003). In Brazil, by contrast, persistent action led from within the government resulted in strong legislation and a nationwide, decentralized program, with training and support cascading down the levels of government (da Costa and Goldfarb, 2003). In South Africa, political and social change created new environments and policy windows that public health advocates were able to turn to their advantage. Comprehensive legislation was enacted in two steps, with a second law strengthening the first. Legislative efforts began with policies to inform consumers and to restrict smoking and advertising. Later, tax increases were put in place and helped reduce consumption. The availabil-

ity of strong local evidence, especially on the economic implications of tax increases, was very important in this case (Malan and Leaver, 2003).

Food and Agriculture Policies

Policies related to dietary changes can be thought of in terms of an integrated food system that goes from “farm to fork.” This system includes food production, food processing, supply chain including food delivery and food availability, food marketing, and food choices both at point of purchase and in individual dietary choices. This system can be influenced by a variety of policies and initiatives in the agriculture sector, the public health sector, and the private sector. By facilitating greater consumption of specific foods, which often replace more healthful traditional foods, changes in agricultural production and policy can be linked with the “nutrition transition,” much of which contributes to rising levels of CVD (Hawkes, 2006). Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that there is potential for cardiovascular health to be promoted by finding economically feasible ways to globalize agricultural and food policies that promote more healthful food production and make more healthful foods affordable to developing country populations, including the poor.

In the past 25 years, agricultural production has increased for all major food groups around the world; however, the rate of increase has been markedly steeper for some foods associated with CVD and other diet-related chronic diseases. One example is Latin America—a major producer of vegetable oils, meat, fish, sugar, and fruit. As part of globalization, agricultural policy in the region shifted in the early 1990s from production to market-led policies. The food-consuming industries (distributors, manufacturers, processors, and retailers) played a key role in this shift. Case studies from Brazil, Colombia, and Chile show that these changes in agricultural policy are linked to changing consumption patterns. In Brazil the government instituted a series of market-led reforms in the early 1990s, which opened up the soybean oil market and encouraged production and enabled greater consumption in export markets (Hawkes, 2006). After investments in technology and infrastructure and trade liberalization during the 1980s in Colombia, the government implemented a market liberalization program, called “Apertura,” which eased imports on feed ingredients and reduced import duties in the early 1990s (Hawkes, 2006). In line with the market-led paradigm, the government in Chile deregulated agricultural policy, privatized land ownership, cut labor costs by dismantling organized activity, provided more favorable conditions for foreign investment, and liberalized trade. These actions increased foreign investment in the fruit industry and were strengthened in the mid-1980s, with the provision of tax incentives to boost exports, increased investment in export-oriented

agriculture, and more provisions to further increase foreign investment (Hawkes, 2006).

Agriculture is also a heavily traded sector, and trade policies affect what food is available within a country and its trading partners. The United States and Europe are major food exporters, and the composition of food available in their developing-country trading partners shows the influence of agricultural subsidies for animal-based products and coarse grains that provide animal feed. A recent study illustrates this by examining the increase in agricultural trade between the United States and Central America, following a new trade pact in 2004. The analysis suggests that “food availability change associated with trade liberalization, in conjunction with social and demographic changes, has helped to facilitate dietary change in Central American countries towards increased consumption of meat, dairy products, processed foods and temperate (imported) fruits. Such dietary patterns have been associated with the nutrition transition and the growing burden of obesity and non-communicable disease reported in the region” (Thow and Hawkes, 2009). The World Trade Organization (WTO) has recognized health consequences as a legitimate concern for trade policy in relation to access to essential drugs. This suggests that countries should have deliberate policies in relation to the health implications of their international trade. However, the WTO has to date not allowed countries to impose trade barriers against unhealthy foods (Clarke and McKenzie, 2007; Evans et al., 2001).

It is also important to note that agricultural trade will not necessarily worsen diets in developing countries. Diets can also be improved by trade through greater dietary diversification, greater food availability, lower consumer prices, and increases in domestic food production spurred by export demand.

In addition to the effects of agricultural production and trade, specific agriculture and food policies can also be linked to changes in food consumption related to CVD risks. For instance, as part of a broader set of chronic disease prevention approaches in Mauritius, the government implemented policies to change the composition of cooking oil made available to the population by limiting the content of palm oil. After 5 years, there were significant decreases in mean population cholesterol levels (Dowse et al., 1995; Uusitalo et al., 1996). Although this was a promising effect, it is important to note the mixed effects of the broader integrated intervention approach, which is described in more detail later in this chapter. In fact, obesity rose during the same time period and there were no other effects on CVD risk factors, indicating that the overall intervention approach was not sufficient to overcome secular trends (Hodge et al., 1996). Therefore, the Mauritius experience serves as an example of how a middle income country can mobilize governmental policies to achieve future health improvement,

but it cannot be used to define the specific tactics that are needed to achieve success, especially without comparison communities (or regions) to control for secular changes. In addition, the specific circumstances of policy implementation and enforcement in a small island nation like Mauritius may not be widely generalizable.

In Poland, changes in economic policy led to reductions in subsidies for animal fat products, and consumption patterns changed, characterized by decreasing amounts of saturated fat and increasing amounts of polyunsaturated fat intake. This was associated with rapid declines in coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality during the same time period (Zatonski and Willett, 2005; Zatonski et al., 1998). However, this is evidence from an unplanned natural experiment using retrospective data, which offers limited lessons on strategic approaches that could be duplicated in other settings. Indeed, in Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria (neighboring countries with similar political and economic changes) there was little apparent decline in ischemic heart disease mortality.

There is also a history in developing countries of price-based policies to influence nutrition outcomes for their populations—primarily basic food subsidies to reduce undernutrition (Pinstrup-Andersen, 1998). Health goals beyond alleviating undernutrition have not always been a consideration in establishing those policies. Analyses of oil price policies in China (Ng et al., 2008) and staple commodity subsidies in Egypt (Asfaw, 2006) suggest that price policies can influence food choices, in these examples with a negative effect on CVD risk. The consumption of edible oils in China has increased substantially with recent drops in edible oil prices stemming from changes in trade patterns (with especially strong effects on the poor) (Ng et al., 2008). In Egypt, the government subsidizes energy-dense foods, and female body mass index (BMI) appears to be influenced by the availability of those subsidized foods, even as the cost of a high-quality diet is out of reach for many in the population (Asfaw, 2006). This analysis does not establish a causal relationship, but it does suggest that government food price policies are influential and that this potential for price policies to adjust consumer demand for specific food ingredients could be considered as a means to promote consumption of healthier foods. The theoretical argument in support of subsidizing healthy foods responds to the problem of food pricing in which healthier foods (fresh fruits and vegetables) are relatively expensive, and energy-dense foods (sugared and heavily processed) are relatively cheap (Drewnowski, 2004). Preliminary research suggests that a “thin subsidy” to lower the price of healthy foods in the United States would be a cost-effective intervention for CHD and stroke (Cash et al., 2005).

The evidence is not yet available as to the effectiveness of the reverse policy—taxing unhealthy food products. Because tobacco taxation has been a very effective and cost-effective policy tool for reducing CVD risk in a

broad range of countries, taxation of other products has been discussed (Brownell and Frieden, 2009) and even tried out on a limited basis in high-income countries. However, there is insufficient evidence on the effectiveness and health impact of this approach (Thow et al., 2010). In addition, for either of these potential price-based policy approaches it should be noted that changing the price of any one category of food or beverage may have impacts on consumption of other categories, which could be for the better or worse of heart health.

There is precedent for strategies to reduce salt in the food supply and in consumption that have been reviewed and documented extensively elsewhere (He and MacGregor, 2009). Salt-reduction strategies in high income countries include public health campaigns to increase consumer awareness of healthy salt intake and to encourage decreased consumption, product labeling legislation, and salt reduction by the food industry (He and MacGregor, 2009). These strategies have the potential to be adapted both to low and middle income country efforts as well as to be scaled up for broader, coordinated global efforts (He and MacGregor, 2009). However, evidence on salt-reduction strategies comes mostly from high income countries, where the majority of salt (80 percent) comes from processed foods (He and MacGregor, 2009; James et al., 1987). Therefore, it is important to note that in many low and middle income countries, even with increasing consumption of processed foods, most of the salt consumed is either added during cooking or in sauces (WHO Forum on Reducing Salt Intake in Populations, 2006). As a result, enhancements to prior policy strategies may be needed when adapting to this context, such as a public health campaign or other efforts to encourage consumers to use less salt. Similarly, precedent for reductions in transfat through policy initiatives, such as the experience in New York City (Angell et al., 2009), offers promise for potential adaptation to a wide range of settings. However, to adapt policy strategies related to the food supply, consideration must be given to the much greater representation of unregulated, informal food sales in most developing countries.

Environmental Policies

There are environmental consequences associated with some of the major CVD drivers that offer an opportunity for shared objectives with the environmental policy sector. Urbanization and increasing air pollution as well as changing global dietary patterns and changing agricultural trends, most notably the rapid increase in meat and palm oil consumption, have implications for CVD risk and also have a significant and often negative impact on the environment (Brown et al., 2005; Langrish et al., 2008; vonBrown et al., 2005; Langrish et al., 2008; vonvon Schirnding and Yach, 2002; Yach and Beaglehole, 2004).

Agriculture and food production in general is a resource-intensive endeavor, and significant portions of the global workforce, land area, water supply, and energy resources are dedicated to it (Schaffnit-Chatterjee, 2009). Meat and dairy production is particularly resource-intensive. Animal-sourced food requires significantly more energy, water, and land use to produce than do basic crops such as legumes, grain, fruits, and vegetables (Popkin, 2003; Steinfield et al., 2006). Indeed, it is estimated that the livestock sector is responsible for more than 8 percent of global human water use and accounts for 70 percent of all agricultural land (30 percent of Earth’s land surface) (Steinfeld et al., 2006).

Livestock production also erodes topsoil, causes land degradation, pollutes water, and threatens biodiversity. Livestock compact the soil and degrade the land, disrupting the water supply, contributing to erosion and necessitating expansion into new grazing lands. These are often created through deforestation, which destroys the habitat of other animals, threatening biodiversity. The livestock sector is also responsible for an estimated 18 percent of greenhouse gas emissions (a higher share than the transport sector)—a result of poor manure management and methane gas emissions from ruminant species such as cattle, sheep, and goats. Furthermore, manure, fertilizers used for growing feed crops, and waste materials from livestock processing are often dumped into waterways without proper treatment, polluting the water supply (Steinfeld et al., 2006).

The rapid rise in palm oil consumption in some low and middle income countries has also had a significant negative impact on the environment and has strained fragile natural ecosystems. In 2001, Malaysia and Indonesia produced 83 percent of the world’s palm oil and were responsible for 89 percent of global palm oil exports. Hundreds of thousands of square miles of rainforest have been cut or burned down to accommodate the growing industry. Palm oil production has also indirectly contributed to further deforestation by displacing local farmers, leading them to expropriate additional rainforest as new land for their subsistence farming. These rainforests are the only habitats for a number of critically endangered species such as the orangutan, the Sumatran tiger, and the Sumatran rhinoceros. Some zoologists believe these species will be pushed into extinction if rainforest destruction continues at its current pace (Brown and Jacobson, 2005; Gooch, 2009).

In addition to contributing to deforestation, palm oil production also contributes to soil and water pollution. As with other crops, extensive use of fertilizers and pesticides on oil palm plantations has led to pollution in the soil and waterways. Additional pollution is caused by oil palm processing, which creates effluent that ends up in rivers and waterways. Indeed, in some Indonesian rivers, pollution from palm oil mill effluent is so severe that fish cannot survive. In the past 6 years, the industry has tried to set

standards to ensure that palm oil production is sustainable; however, rainforests continue to be destroyed and effluent continues to be improperly dumped into waterways. While the production of some other oil crops leads to water pollution and rainforest destruction (for example, parts of the Brazilian Amazon are now being cut down to make way for soybean production), the exponential increase in palm oil use combined with the projected future rise in global demand make it a particularly glaring example of potential long-term harmful environmental effects (Brown and Jacobson, 2005; Gooch, 2009).

This opens a door for shared approaches between those trying to promote cardiovascular health and those trying to promote environmentally sustainable development. These shared approaches may include policies to limit overproduction of palm oil production and to encourage shifts in agricultural production from meat and dairy to more fruits and vegetables. Tobacco production, processing, and consumption have also been associated with negative environmental consequences (Bump et al., 2009). This provides an additional rationale for synergistic efforts to overcome the technical, political, and commercial barriers to implementing policy changes in the food and agriculture sectors that both promote health and protect the environment.

Urban Planning Policies and the Built Environment

A broad range of structural factors comprise the “built environment,” and many of these factors contribute to health outcomes. They encompass factors such as chemical, physical, and biological agents, as well as physical and social environments, including housing, urban planning, transport, industry, and agriculture (Papas et al., 2007). Thus urbanization is another area for potential synergy between promoting environmentally sustainable development and promoting cardiovascular health.

As described in Chapter 3, trends show that the changes in the built environment due to urbanization are generally associated with several risk factors for CVD, including an increase in tobacco use, obesity, and some aspects of an unhealthful diet, as well as a decline in physical activity and increased exposure to air pollution (Brook, 2008; Gajalakshmi et al., 2003; Goyal and Yusuf, 2006; Langrish et al., 2008; Ng et al., 2009; Steyn et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2008; Yusuf et al., 2001).

Motivated by the growing prevalence of obesity in many developed nations and the potential public health impacts stemming from subsequent CVD and diabetes, studies conducted within the United States, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand over the past three decades have successfully demonstrated the correlation between different aspects of the built environment and physical activity levels (Humpel et al., 2002). These correla-

tions provide a compelling rationale, and reports such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Community Guide and the Institute of Medicine’s Local Government Actions to Prevent Childhood Obesity (2009) have produced guidance for different types of policy initiatives at several levels of jurisdiction, including changes to the built environment.

However, there is a lack of prospective studies investigating the effect of introducing changes to the built environment on individual and population health. These prospective data are much needed as the current cross-sectional analyses have limited ability to demonstrate causality. For example, it is difficult to ascertan if built environments that are more conducive to healthy lifestyles lead to increased physical activity, or whether individuals who are more physically active are more likely to live in a neighborhood that is more conducive to walking, bicycling, or playing sports. It is difficult to obtain prospective data, as there are a wide variety of exogenous variables to interfere with potential findings. In addition, these studies would require a significant financial investment, either on the part of the research funding institution or the local community (Sallis et al., 2009). There has also been little economic analysis of the potential costs associated with modifying an element of the built environment, which could be a barrier in developing countries.

In addition, it is important to note that the majority of data on the correlation of environments and increased physical activity comes from high income countries. With the exception of some work in Latin America described below, there is a lack of evidence from a range of developing country settings, and most guidance documents do not address generalizability or adaptation to low and middle income country settings. While there may be some commonalities between individuals from both urban and rural regions of the developed and developing world, differences in social norms, culture, existing built environment, and local variations in baseline daily activity levels are likely to have a substantial impact on the potential effectiveness of a change in the built environment in leading to behavior change.

On the other hand, low and middle income countries undergoing rapid development and urbanization provide promising opportunities to help fill the evidence gap through future prospective research given the multitude of neighborhoods and cities in the early stages of land use development. The need for investment of resources in this research may be lessened in settings where the intervention is not an alteration of an existing environment but rather an element of design planning where investment has already been committed to future urbanization projects. In fact, prospective studies in the context of planned urbanization in rapidly developing countries could also provide better evidence on the monetary investments required to achieve “successful” future urban design.

A few public health initiatives in middle income countries in Latin America, such as Muévete in Bogota and Agita São Paulo in Brazil, have altered the local built environment as a component of an overall program, but evaluations of their results are limited (Gamez et al., 2006; Matsudo, 2002). The Agita program in Brazil is one of the few programs with an evaluation that uses health outcomes. This was a multicomponent program that included changes in the environment through an increase in the number of walking areas, facilities for bicycling, and recreational facilities. Changes related to the practice of physical activity during the intervention period were observed. An annual survey showed that over 5 years there was a decrease from 14.9 percent to 11.2 percent in the population defined as inactive, a decrease from 30.3 percent to 27 percent in the population deemed irregularly active, and an increase from 54.8 percent to 61.8 percent in the population considered active or very active. Changes were also observed in targeted groups, such as groups of patients suffering from hypertension or diabetes and patients and workers in hospitals and health centers (Matsudo et al., 2006).

In summary, there is limited evidence of the effects on CVD-related outcomes of strategies and investments to alter the existing built environment, and urban planning policies are likely not a CVD priority in many low and middle income countries. However, for policy makers in countries undergoing rapid urbanization, there is a strong evidence-based rationale to take advantage of the opportunity going forward to implement and evaluate strategies to encourage cardiovascular health by making cities walkable, cyclable, safer, and free of air pollution. A more “heart-healthy” approach to growth and urbanization provides opportunities to avoid negative impacts, and possibly to even use the growing investment in new city development for health gains, including CVD prevention and health promotion.

Health Communication Programs

Health communication programs are typically designed to reach a large audience with messages as part of their established exposure to communication sources such as radio, television, billboards, newspapers and other printed material including mass mailings, and the Internet. Such exposure is often passive, relying on routinely accessed sources, rather than requiring the motivation of actively seeking a new communication source by an individual. Communication programs may affect behavior through three paths: (1) by directly educating and persuading individuals to change their behavior (e.g., by changing people’s minds and providing skills needed to quit smoking); (2) by changing the expectations of peers in social networks, which in turn influence individual behavior (e.g., by changing friends’ willingness to condemn smoking); and (3) by changing public opinion to

influence public policy, which then influences individual behavior (e.g., by changing the political climate to permit regulation of secondhand smoke and thus reducing opportunities for individuals to smoke).

The effectiveness of policies and programs can be enhanced if linked to health communication programs targeted to the same objective—for example, to complement lobbying of policy authorities and food manufacturers to restrict salt content with public education about salt reduction. In addition, linking communication programs to policy approaches can make them more likely to gain presence in the public mind and thus gain public support. A communication program may also be designed to precede the policy change to nurture the public support needed for legislative action. Health communication strategies can also be an important complementary component of health systems and community-based approaches. Depending on the infrastructure within a country, communication and health education efforts can occur at multiple levels, from the national government to local authorities and community-based organizations.

The following section describes the evidence and considerations for designing and implementing communication campaigns at scale under the kinds of conditions that would be expected in real-world public health systems rather than research programs. An analysis of the current literature, described in more detail below, indicates that what might be most feasible for short-term implementation, and for coordination with policy approaches, is a focus on reasonably narrowly defined CVD-related targets, rather than trying to change all determinants of CVD at once. This focus can be most effective when using multiple intervention approaches to achieve the same ends, with large-scale communication programs as one important component.

CVD-Related Communication Campaigns in Low and Middle Income Countries

There is currently very limited evidence about the effects of communication interventions on CVD-related behaviors (or morbidity) in low and middle income countries, with few reported examples of communication programs with rigorous evaluations. The evidence is also challenging to interpret because large-scale communication programs tend to be components of multifaceted programs. Even when such multifaceted programs are evaluated, the effects of separate components are difficult to distinguish. In addition, in many reported evaluations no control condition is present, and as a result the effects of secular change can be difficult to discriminate from the effects of intervention efforts.

There are descriptive reports about some programs implemented in middle income countries that incorporate communication elements (Grabowsky

et al., 1997). Some of these reports, described below, describe an evaluation and infer effects on CVD-related outcomes, but in some cases these effects are weakly supported, with little evidence of sustained impact.

The Coronary Risk Factor Study (CORIS), conducted in South Africa from 1979 to 1983, was a multilevel, multifactor intervention in which most of its effects were explained by use of a mass media campaign (Rossouw et al., 1993). There were three nonrandomized, matched towns: two treatment and one control. There was a mass media component plus community “events” in one town, and the same with the addition of a high-risk counseling program in a second treatment town. Before-and-after cross-sectional surveys measured knowledge of risk factors, smoking habits, and medical history as well as BMI, blood pressure, and cholesterol. Blood pressure, smoking, and composite risk were lowered compared to the control town, but there was no difference between the two treatment conditions. Thus, this was a replication of a successful use of a mass media strategy and was a test of these methods in a middle income country. However, the program focused only on middle income white South Africans, so the generalizability to other low and middle income countries may be limited. After the initial intervention was implemented, a maintenance program was established and surveyed at 4-year intervals. In a review of the project’s 12-year results Steyn et al. (1997) concluded that while the CORIS community intervention was successful in the short term, in the longer term both the control group and one of the two intervention groups showed decreased risk factors. The authors speculate that this can be explained by strong secular trends and local factors. This highlights the challenge of maintaining long-term effects in these interventions.

The Healthy Dubec Project was a single-community, 2-year education campaign in the country that was then Czechoslovakia, with a before-and-after analysis that surveyed height, weight, blood pressure, and cholesterol, as well as sociodemographic variables and behavioral CVD risk factors (Komarek et al., 1995). The education campaign was delivered primarily through print media, including newspaper columns and brochures distributed at community sites and events and to residents’ homes. Significant improvements were noted in blood pressure, cholesterol, and saturated fat intake. No effect was observed on smoking or BMI (Albright et al., 2000). This provides another example of some documented effects in a middle income country. Like many of the available examples of evaluated programs, this was a single-community model, which carries less evidentiary weight than studies with one or more control communities. Nonetheless, this study demonstrated the ability to achieve culturally appropriate adaptations of the print materials used in the Stanford Five City Project. This is an important lesson about the potential for transferability of materials tested in high income countries.

In Poland, the Polish Nationwide Physical Activity Campaign “Revitalize Your Heart” had the main goal of promoting an active lifestyle through education via mass media, including large broadcasting stations, public television, popular newspapers, magazines, and leading electronic media. This was accompanied by a country-wide contest and different local interventions (sports events, outdoor family picnics). Questionnaires administered to the participants of the contest and more than 1,000 people in the Polish population showed increased awareness of low physical activity as a problem. In addition, almost 60 percent of participants reported increased frequency and duration of exercise during the campaign (Ruszkowska-Majzel and Drygas, 2005).

Brazil’s Agita intervention, described in the previous section, had two main objectives: to increase the population’s awareness of how important physical activity is to health and to increase the level of physical activity within the population (Matsudo et al., 2003). To achieve these objectives, the program organized three main types of interventions: mega-events, specific activities with partner institutions, and partnerships with community organizations. The program succeeded in obtaining significant media coverage: 21 million people were reached by means of at least 30 newspapers distributed in the state’s various cities, as well as at least 7 national newspapers and 4 broadcasts on national television (Matsudo et al., 2002). As described in the previous section, an annual survey carried out over 4 years showed increased self-reported levels of physical activity (Matsudo et al., 2006).

Potential Lessons from CVD-Related Communication Campaigns in High Income Countries

Although evidence is limited from CVD-related programs in low and middle income countries, there are evaluations of programs in high income countries that offer some lessons for designing and implementing programs in low and middle income countries. This includes those that focused on a single outcome (smoking, physical activity, high blood pressure control, cholesterol reduction, salt consumption) and those that addressed multiple CVD risk factors within a single program. Some of these programs (whether they address a single risk factor or multiple risk factors) make communication a central (or the central) component of the intervention. Others make use of communication as one component of a multicomponent intervention. Even from these high income country programs the evidence is mixed, but a few general conclusions can be drawn.

Tobacco Use There is substantial evidence in support of youth antitobacco communication programs, which is described in more detail in

Chapter 6 (Wakefield et al., 2003). There is also some evidence, particularly time-series evidence, supporting the influence of communication on adult smoking (National Cancer Institute, 2008). A detailed synthesis of evidence on the effectiveness of media strategies employed in tobacco control campaigns, including marketing and advertising and news and entertainment media, can be found elsewhere and is not repeated here (National Cancer Institute, 2008).

In addition to tobacco control campaigns, there is good reason to believe that important reductions in tobacco use in part reflect deliberate efforts by the antitobacco movement to shift public opinion to recognize the dangers of secondhand smoke, to publicize the deliberate efforts by the tobacco industry to deceive the public and addict children and young people, and to achieve recognition of the right to restrict the free exercise of individual smoking rights when they affect the health of others. These efforts often included deliberate efforts to shape media coverage of the tobacco issue, and to use that as a path to changing public policy (Shafey et al., 2009). While it is not possible to make definitive attributions of influence, it is reasonable to connect this form of media advocacy to behavior change and to view it as an important model for tobacco control in low and middle income countries as well as for possible extension to other areas of behavior relevant to CVD.

Tobacco also offers an example of how communication can be used in ways that run counter to the promotion of health. For instance, the tobacco industry has used the media to promote tobacco products (Sepe et al., 2002; Shafey et al., 2009; Tye et al., 1987) and has spent billions of dollars a year on marketing initiatives in the United States (Frieden and Bloomberg, 2007). Tobacco advertising has proliferated on the Internet, and pro-tobacco messages are widely available on social networking websites (WHO, 2008). However, the media can also be effectively used for counter advertising, as has been demonstrated in different regions (Emery et al., 2007; Fichtenberg and Glantz, 2000; Goldman and Glantz, 1998; Ma’ayeh, 2002; Pierce, 1994). Moreover, controls on tobacco advertising and marketing can be effective if they are comprehensive, include both direct and indirect advertising and promotion, and are combined with other antitobacco efforts (Frieden and Bloomberg, 2007; Pierce, 1994; Saffer and Chaloupka, 2000).

Other Risk Factors There is some evidence in high income countries of the success of communication efforts in reducing salt consumption (He and MacGregor, 2009) and improving awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension (Roccella and Horan, 1988). There is less evidence for communication efforts alone to influence physical activity outcomes, par-

ticularly sustained physical activity changes (Kahn et al., 2002; Taskforce on Community Preventive Services, 2002).

There is also some credible evidence for the effects of communication programs targeted to multiple CVD-related risk factors (Schooler et al., 1997). Six successful community-based, multilevel, multifactor CVD prevention projects in high income countries in the 1970s and 1980s had effects that can be attributed largely to their use of a mass media health communication approach, which is the aspect of these programs discussed here. These projects are also discussed later in this chapter in the section on community-based programs. They were done in the United States, Finland, Australia, Switzerland, and Italy and have been reviewed extensively elsewhere (Schooler et al., 1997).

The North Karelia project in Finland continued for many years and, after its successes on all CVD risk factors during the first 5 years, its methods were applied throughout Finland and culminated in major declines in CVD mortality (Puska et al., 1995). The Stanford Three Community Study showed evidence for effects on important risk factors of smoking, blood pressure, cholesterol, and body weight and a large decrease in total CVD risk (Farquhar et al., 1977; Williams et al., 1981). The Stanford followon study (the Five City Project) showed relatively large effects on smoking and blood pressure, with somewhat lesser effects on overall risk than in the previous Three Community Study, and no effect on body weight (Altman et al., 1987; Farquhar et al., 1990; Sallis et al., 1985). The Three Community Study was also the basis for the design of the CORIS project described earlier (Rossouw et al., 1993). Indeed, the North Karelia program and Three Community Study galvanized substantial further major trials and worldwide consideration of community-focused programs to address CVD burdens.

Across the major projects that followed, including CORIS in South Africa, there has been replication of reductions in smoking and blood pressure in all seven projects, cholesterol in three, and body weight in two (Schooler et al., 1997). These replications provide evidence that rather small cities and towns in high income settings appear to have responded well in their risk-factor change to educational programs based largely on mass media.

In contrast, two other large programs that began somewhat later, in the mid-1980s, the Minnesota Heart Health Project and the Pawtucket Heart Health Project in Rhode Island, did not show appreciable effects (Carleton et al., 1995; Luepker et al., 1996). A likely reason for the lack of effect in the latter two programs is their relative lack (Luepker et al., 1996; Mittelmark, 1986) or absence (Carleton et al., 1995) of mass media. Other subsequent studies in Europe also tended to have greater success when

extensive broadcast and print media were used (Breckenkamp et al., 1995; Greiser, 1993; Schuit et al., 2006; Weinehall et al., 2001). These programs are also discussed again in the community interventions section below.

Another factor that may affect the success of health communication campaigns is secular trends that influence the novelty and potential effects of the campaign’s messages. The earlier studies, done in the 1970s and early 1980s, reflect the possibilities for mass education at that time, when radio and newspapers were a more important news source than at present, and while the trends for risk-factor levels and CVD events were beginning to decline. It was also a time before major changes had occurred in smoking rates, before the messages became more commonplace in the settings where they were implemented, and before the relatively easy changes in diet had occurred for many in the target populations. These studies also preceded the expansion of many of the broad drivers of CVD risk. Therefore, these earlier projects may have faced fewer obstacles to change than might be faced earlier or later in the epidemiological transition cycles.

Potential Lessons from Other Health Communication Programs in Low and Middle Income Countries

Even when communication programs in high income countries have demonstrated success, these programs may be difficult to generalize to developing-country contexts. Because there are so few models of CVD-related communication programs in low and middle income countries, it is worth looking to programs with evidence of effectiveness in these settings that have been targeted to other health-related behaviors for possible models of design and implementation, especially those programs that target outcomes that similarly require sustained behavioral change.

There is a rapidly growing evidence base for communications in low and middle income countries related to a range of health issues. For example, there is credible evidence for communication program effects on child survival-related outcomes including immunization (a repeated behavior requiring parents to bring their children to a clinic or other site), use of rehydration solutions for diarrheal disease (a repeated behavior undertaken at home in response to disease symptoms), and breastfeeding (a behavior already often performed but the campaigns are meant to shape the behavior and extend it in time) (Hornik et al., 2002). In addition, there is support for the effects of communication programs on HIV risk-related behaviors, particularly condom use with “casual” partners, and on family planning behaviors, particularly increasing initial visits to providers of contraceptive services (Bertrand et al., 2006; Hornik and McAnany, 2001).

Principles to Guide Future Design and Implementation of Communication Programs

Health communication campaigns require careful planning, ideally involving professionals with adequate training in health communication. Some of the key principles for designing and implementing these programs are described briefly here; existing resources that have informed communication strategies in developing world settings can provide more thorough guidance for planning CVD-related interventions (see, for example, NCI, 2002; O’Sullivan et al., 2003; Piotrow et al., 2003; Smith, 1999).

Strong communication programs choose messages based on behavior change theory and reflect thorough knowledge of their target audience, in terms of both their structural context—how the old and new behaviors fit into their lives—and their cognitive response to the behavior. Often audiences are heterogeneous and message strategies have to be differentiated by audience segment; formative research to precede widespread launching of a campaign can be used to test prototypes of the campaign’s messages with representative subsets of the intended target audience.

From the epidemiological perspective of preventing CVD, it is natural to look at the set of risk factors for CVD as interrelated and to consider how to construct a program that will influence all those factors. However, from the perspective of trying to prioritize and act synergistically with policy interventions to achieve change in risk factors or the behaviors associated with them, it may not be wise to try to address multiple CVD risk factors in one campaign. There may be greater potential to achieve behavior change by constructing independent programs that address each factor by itself (e.g., tobacco use, salt consumption, transfat consumption, saturated fat consumption, physical activity, and obesity). The institutional actors relevant to each of those risk factors are distinct, and the way one might construct communication campaigns for each can be sharply different. For example, there may be different focus audiences; different motivations for adopting new behaviors; and different types of behaviors with regard to timing, difficulty, and opportunity to act. The lack of commonalities among, for example, quitting smoking, maintaining physical activity, or purchasing foods low in saturated fats makes it very difficult to design one communication strategy that will maximally affect all relevant behaviors. However, hybrid campaigns may be preferred in some cases for greater efficiency when, for example, the trained health education staff is already in place.

A communication program can get exposure for the intended message through a number of means. For example, it can be required if the government controls media outlets. However, health authorities may not have access to the media even when it is government controlled. Exposure

can also be purchased, although purchasing media time can be expensive especially because the audience needs to be reached repeatedly with the intended messages. If it is necessary to purchase media time, achieving high levels of exposure and maintaining exposure over time could become the most expensive element of communication programs. Low and middle income countries therefore have an economic incentive to seek strategies to ensure the availability of low-cost educational media programming. Another strategy for program exposure is to make news and attract coverage from media outlets (e.g., National Power of Exercise Day in Thailand celebrity endorsement and involvement). However, media coverage may not be reliable and can be biased depending on factors such as whether media outlets are private entities or government agencies, and whether or not they operate within a system that guarantees freedom of the press.

New communications technologies may also provide opportunities to reach people with health-promoting messages and research suggests that channels such as computer programs, websites, and videogames may reach audiences missed by traditional health communication (Barrera et al., 2009; Boberg et al., 1995; Hawkins et al., 1987; Levy and Strombeck, 2002; Walters et al., 2006). However, although programs are emerging that depend on interactive communication technology, there is insufficient evidence at this time to determine if these approaches will be effective in low and middle income countries. One potential disadvantage to these kinds of digital media interventions (at least as they have been implemented up until now) is that they require audiences to seek out, have access to, and make continuing active use of the sources. This is unlike mass media interventions, which assume that the audience can be reached passively through its routine use of media. The requirement for active seeking is likely to limit the proportion of the unreached population who are engaged. This essential weakness runs up against a frequent goal of population-focused programs, which is to involve people who are not substantially motivated to act.

Another critical aspect of effective communication programs, like most behavior change programs, is that they cannot be single, fixed interventions. Rather, they need to evolve in response to changes in their audiences, to changes in the context in which the behavior is to be performed, and to changes in the social expectations of those around the individual. A good program is not defined by its specific communication actions (such as the number of messages on specific channels over a specific time period) but by the methods employed for changing messages and diffusion channels as circumstances change over time. They are more analogous to what a practicing physician might do, ideally, in working with a patient whose symptoms and illness level, readiness to comply with recommendations, and family support change over time.

Finally, capacity is a consideration that cannot be ignored since the ca-