1

Background

ESTABLISHING A COMMON TERMINOLOGY

Although all disorders of the nervous system are related due to their common origin, the absence of a common terminology can negatively impact the establishment of common policies. Throughout the workshop, participants used many different terms to describe the many mental health, neurological, and substance use (MNS) disorders that impact the populations of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). However, Marcelo Cruz, president of the Global Network for Research on Mental and Neurological Health, Ecuador, suggested that in order to include a wide range of disorders that are often otherwise separated into treatment silos in developed countries, such as neurology, psychiatry, psychology, substance use etc.; the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) term “MNS disorders”—covering mental health, neurological, and substance use disorders—should be adopted. Workshop participants agreed, and thus it was adopted for use during the workshop and in this summary.

MNS disorders encompass a wide range of conditions of the brain from depression to epilepsy to alcohol abuse. These and the many other MNS disorders found throughout the world are often linked in a complex way with other health conditions (WHO, 2008a). They may be comorbid or risk factors for noncommunicable and communicable diseases like HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis. MNS also factors into sexual and reproductive health in, for example, postpartum depression or injuries from violence or traffic accidents. Furthermore, depression and substance use disorders adversely affect adherence to treatment for other diseases, often exacerbated by poverty and the presence of endemic infectious diseases.

The scientific underpinnings of MNS are now better understood. Most have their origins in abnormal brain structure or function. Therefore, given the related nature of MNS, better integration of these specialties is needed, especially neurology and psychiatry (Fenton et al., 2004;

Hyman, 2007; Insel and Quirion, 2005). In developed countries these conditions are typically treated by highly trained specialists; however, developing countries do not have enough MNS specialists, and other resources, to diagnose and treat all comorbidities. This often can result in a failure to account for diagnostic complexity where it exists (Njenga, 2004). Therefore, casting a wide net over the spectrum of disease is especially important given the resource-constrained nature of SSA and the often comorbid nature of MNS disorders in the region.

This sentiment was echoed repeatedly by workshop participants, who noted that SSA countries have an opportunity to avoid the consequences that have resulted from separating disorders into various separate “mental health” or “neurology” silos, as other countries have done, and instead recognize the related nature of MNS disorders and thus leverage limited resources across the wide (and integrated) range of MNS disorders, in order to help patients who need care. Specialists are not needed specifically for neurology or psychiatry; individuals are needed who care for disorders of higher brain function (Hyman, 2007). Advancing the use of the term “MNS disorders” will allow policy makers, healthcare providers, and advocacy groups to focus on the widest range of diseases and medical conditions, explained Sheila Ndyanabangi from the Ministry of Health in Uganda.

THE MNS DISEASE BURDEN

“Disease burden” is a term used to convey how prevalent various diseases are. Donald Silberberg, professor at the Department of Neurology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, put it plainly, “The burden of disease can be viewed as the gap between current health status and an ideal situation in which everyone lives into old age free of disease and disability. Causes of the gap are premature mortality, disability, and exposure to certain risk factors that contribute to illness.”

One common source of disease-burden guidance comes from the regular World Health Reports by the WHO, which uses the disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) method to assess the impact of certain diseases. DALYs is the sum of potential years of life lost due to premature mortality, plus the years of productive life lost due to disability. An acknowledged shortcoming of the DALYs metric is that it does not include the social or economic impacts on individuals, families, communities, or health systems—or the true burden these diseases have on the lives of those who suffer from them and those who care for them. Recognizing

these limitations, on a DALYs and years-living-with-disability basis, Africa at first glance seems to have a lower disease burden due to neuropsychiatric disorders than the rest of the world (Table 1-1).

Acquiring accurate prevalence data of MNS disorders can be difficult. But as Steven Hyman, provost of Harvard University, explained, the extraordinary burden of infectious disease and other conditions such as malaria and tuberculosis have understandably, but at the same time tragically, interfered with the recognition of burden of MNS disorders. The sheer numbers of deaths and disabilities caused by HIV/AIDS, malaria, other infectious disease, and diseases of poverty overwhelm the disease burden that can be attributed solely to MNS disorders (WHO, 2001). Because of the high need for treatment of infectious diseases, healthcare resources are focused on diagnosing and treating those diseases, and MNS disorders are often overlooked, ignored, or misdiagnosed. The result is a systemic underreporting of the true disease burden created by these disorders.

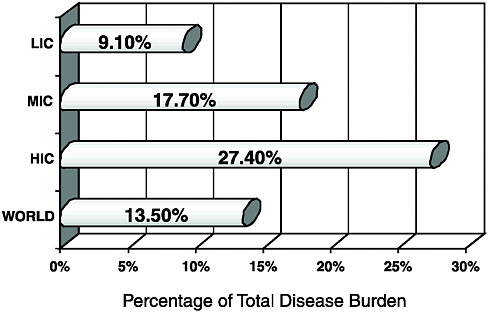

Vikram Patel from the University of London highlighted data from the WHO’s 2006 Global Burden of Disease report, which shows that nearly 10 percent of the total disease burden in the world’s lowest income countries is attributable to neurological and psychiatric disorders (Global burden of disease and risk factors, 2006) (Figure 1-1).

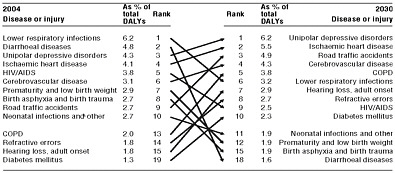

The burden of MNS is both significant and significantly underreported. It is also on the rise. The WHO estimates that depression will become the leading cause of years lost due to disability by 2030. This is not surprising knowing the comorbidity of depression with cerebrovascular disease, which is also expected to move up from sixth to fourth by

FIGURE 1-1 Disease burden of neuropsychiatric disorders.

NOTE: HIC = high-income countries; LIC = low-income countries; MIC = middle-income countries.

SOURCE: Global burden of disease and risk factors, 2006.

2030. Ischemic heart disease and traffic accidents (ranked second and third, respectively) also are intricately linked with MNS disorders (Figure 1-2), making the true burden of MNS disorders both overwhelming and extremely difficult to calculate.

MNS Disorders in Sub-Saharan Africa

While many MNS disorders are common throughout the world, their relative impact on each region varies. Silberberg noted that with respect to MNS disorders, “The leading problems that are more common in sub-Saharan Africa are birth defects affecting the brain and spinal cord; mental retardation; cerebral palsy; bacterial, viral, and parasitic infections of the nervous system; epilepsy; and head and spinal cord trauma, mostly from road traffic accidents.” Although the number of comprehensive epidemiology studies is limited, it is widely accepted in the provider

FIGURE 1-2 Predicted changes from 2004 to 2030 to the leading causes of burden of disease worldwide.

NOTE: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HIV/AIDS = human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome.

SOURCE: WHO, 2008b.

community that cognitive disorders, dementia, epilepsy, and stroke are common “secondary diseases” attached to conditions that are widespread in the region, including tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, malaria, and sickle-cell anemia (The global burden of disease: A comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020, 1996). Widespread in sub-Saharan Africa, HIV/AIDS and malaria have significant mental health implications. Not only are there common mental health disorders that are due to, or associated, with these diseases, such as depression and substance use, but there are also many neurological disorders that can arise as direct complications from opportunistic infections (UNAIDS, 2007).

Many other MNS disorders also occur at higher rates in sub-Saharan Africa, and many disorders have predictably worse outcomes than in the developed world. For example, in Tanzania, individuals who have suffered a stroke have 10 times the mortality rate when matched for age compared with those in the Western world (Matuja et al., 2001; Walker et al., 2000). Despite the difficulties associated with diagnosing cases, the prevalence rate of cerebral palsy is at least 4 times as high in some SSA countries compared to rates in Europe (Silberberg, 2009). Epilepsy due to trauma at birth and head injury in later life is probably one of the most common MNS disorders in Africa. Childhood infections, including measles, are other common causes of epilepsy, a condition that is comor-

bid with mental illness in some cases (Njenga, 2004). Likely surpassing epilepsy in numbers of those affected are diagnosed and undiagnosed cases of depression that may or may not be linked to infectious diseases or substance use. Because these conditions (epilepsy, HIV/AIDS, malaria, and substance use) appear most prevalent in SSA, they have been singled out and addressed in more detail below.

The Disease Burden of Mental Health Disorders

Mental disorders are health conditions that can affect an individual’s cognition, emotion, and behavioral control and cause the person distress and difficulty in functioning. Some of the most common disorders include depression, schizophrenia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Such disorders tend to begin early in life and often run a chronic recurrent course. Although most experts agree that mental disorders represent a substantial portion of the world’s disease burden, these disorders remain highly neglected and stigmatized, making prevalence data difficult to obtain and interpret (Horton, 2007). From the limited data available, it appears that depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder are the most prevalent in SSA; however, the leading mental disorders—depression and anxiety—are often grouped together and referred to as “common mental disorders (CMD)” (Silberberg, 2006). The causes of CMD in sub-Saharan Africa might be from alcohol and substance abuse, conflicts and war, HIV/AIDS, gender-based violence, or other childhood maladies resulting in stigmatization from an early age.

Regardless of the cause, mental disorders receive very little attention from most African governments. Health in general is still a poorly funded area of social services in most African countries and, compared to other areas of health, mental health services are poorly developed even though mental disorders account for approximately 350 million DALYs lost per year in SSA—significantly greater than developed countries at 150 million DALYs per annum (WHO, 2006b). Table 1-2 shows the leading cost in DALYs is due to CMD. Also noted in the table are the other major psychiatric disorders in SSA that contribute significantly to the years of productive life lost due to these disabilities as well as the economic benefits of cost-effective treatments.

TABLE 1-2 Disease Burden and Cost-Effective Treatment of Selected Major Psychiatric Disorders in Sub-Saharan Africa

|

Disorder |

DALYs per Year per 1 Million Population |

Cost-Effective Treatment |

|

Depression |

4,905 |

proactive care with newer antidepressant drug (SSRI; generic) |

|

Bipolar disorder |

1,803 |

older antipsychotic drug plus psychosocial treatment |

|

Schizophrenia |

1,716 |

older mood-stabilizing drug plus psychosocial treatment |

|

Panic disorder |

777 |

newer antidepressant drug (SSRI; generic) |

|

SOURCE: WHO, 2006c. |

||

The Disease Burden of Epilepsy

Throughout the workshop, participants stressed that although substantial prevalence data are not available, epilepsy is one of the most common MNS problems in SSA. The absence of data is the result of a variety of reasons. There is a lack of specialized personnel, particularly in neurology, needed to recognize the symptoms. Furthermore, diagnostic equipment is not available—there are 75 electroencephalographs and 25 computed tomography scanners in tropical Africa, which are frequently out of order—limiting the ability to accurately ascertain a diagnosis (Preux and Druet-Cabanac, 2005). Furthermore, screening questionnaires typically used to identify patients with epilepsy do not translate well across different populations with diverse social or cultural backgrounds, medical records are often incomplete, and terminologies for classifying seizures and epilepsy differ among studies, making comparisons difficult to impossible, which all further complicate diagnosis and epidemiology of epilepsy.

Despite these limitations, epilepsy is reported to affect 2–10 percent of the African population. The prevalence varies from country to country, and—due to the reasons cited above—it can vary from study to study within a country. But what is clear is that the number of persons in SSA suffering from epilepsy is significant. In Lesotho in 2008, “Epilepsy (was) the main mental health condition, accounting for 42 percent of out-patient department visits,” said Mathaabe Cecilia Ranthimo, acting director for Mental Health Services at the Ministry of Health and Social Wel-

fare. Osman Miyanji, chair of the Kenya Association for the Welfare of People with Epilepsy, said that although one study indicated the prevalence was about 1.8 percent in Kenya, other studies have shown different results. He believes the true number is higher (Miyanji, 2009). Although the prevalence in Tanzania ranges from 2 to 3.8 percent (Box 1-1), depending on the study, a researcher in Rwanda found approximately 4.9 percent of the population to have epilepsy in 2005 (Simms et al., 2008). In Mozambique, 13.5 percent of all households reported a case of seizure disorder, according to one report (Silberberg, 2009).

The wide range of reported numbers just on this one disorder clearly illustrates the difficulty in obtaining quality epidemiological data for policy makers. Although a number of factors can account for the reported high rates of epilepsy in SSA, common causes of epilepsy are likely to include infectious diseases, trauma, alcohol consumption, and birth asphyxia resulting from poor maternal health care—all of which are known to be high in parts of SSA. In addition, due to poor living conditions characterized by overcrowding, poor water supply, and bad sanitation, there is a high prevalence of communicable diseases such as malaria, meningitis, cysticercosis, and tuberculosis, which are also frequent causes of epilepsy. The data suggest, however, that contrary to the disease burden numbers previously presented, the prevalence of epilepsy is at or above the levels found in the United States and other parts of the developed world.

The Disease Burden of HIV/AIDS

Saying that HIV/AIDS has a large impact in SSA is a gross understatement. Sixty-eight percent of people living with HIV worldwide live on the African continent, and every year, 76 percent of all AIDS-related deaths in the world occur there. In 2007, Africa accounted for 68 percent of new HIV infections in the world. In some regions, more than 20 percent of the adult population is infected, including more than 26 percent of the population of Swaziland (UNAIDS, 2007).

Thanks to better HIV/AIDS treatments using antiretroviral therapies, morbidity and mortality have decreased in HIV patients with advanced disease. However, as the number of patients on antiretrovirals increases, more and more people are living longer with HIV, raising new challenges. Furthermore, only about 30 percent of Africans who need antiretroviral therapy actually receive appropriate care (AVERT, 2008; WHO,

2008a), and current treatment guidelines often delay initiation of antiretroviral therapy during the early stages of disease. One common guideline recommends initiating therapy if a patent’s CD4 white blood cell count falls below 200 (WHO, 2006a). But new studies suggest that may be too late to prevent neurological damage. Angela Kakooza-Mwesige, a neurologist from Makerere University School of Medicine, stated: “Accord-

|

BOX 1-1 Epilepsy Care in Tanzania Epilepsy is the most commonly seen neurological disorder in Tanzania, with a prevalence of 2 to 3.8 percent. However, only a small percentage of these patients—perhaps as few as 5 to 10 percent—receive appropriate care and adequate therapy (Matuja et al., 2001). People with epilepsy in Tanzania have twice the mortality rate of the general population when matched for age (Jilek-Aall and Rwiza, 1992). The area of Mahenge in the Morogoro region of the country has had an epilepsy clinic since it was started by Louise Jilek-Aall in 1959. What began as a small clinic with 50 patients grew to 200 patients within 3 years. Six years ago, the Tanzanian health system took over the clinic because it was no longer staffed. Since that time, a collaborative group has worked to improve epilepsy care for people in the region. Bringing together the government, non-governmental organizations, and private partnerships, the collaboration has worked to improve the lives of people with epilepsy in the area, and remarkable advances have been made:

Because of these improvements, the clinic in Mahenge now sees 4,000 patients a year, and seizure frequencies are down 60 to 70 percent since 2003. Mortality has also decreased (Winkler et al., 2010). These improvements in care are largely the result of strong collaborations. The government, which was involved since the beginning, supplies the drugs to the district hospitals for free. The Tanzania Epilepsy Association supplies personnel and educational materials. Rotary International supplied motorbikes to the district for use in monthly follow-ups and home visits. The district maintains the vehicles and supplies fuel. The Savoy Foundation of Canada, the Mahenge Dioceses of the Catholic Church, and the Kasita Seminar all work together to help rehabilitate epilepsy patients. Research is done by Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, along with colleagues from Germany and Austria. In short, disparate groups came together and made a huge impact in the lives of the local patient population. |

ing to the molecular studies, we are seeing that cognitive impairment occurs much, much earlier.”

Neurological complications occur in 39 to 70 percent of patients with symptomatic HIV infection, and most are caused by opportunistic infections, which are complex and difficult to diagnose and treat with limited resources in most SSA healthcare systems (Odiase et al., 2006). Even though low-cost treatments are available for opportunistic infections associated with HIV, they are often inaccessible to most individuals living with HIV. Even for otherwise healthy patients, an antiretroviral regimen can require the patient to take many pills each day, leading them to believe they have “pill overload” and thus causing difficulty in adhering to the medication regimen, Kakooza-Mwesige said. When neurological disorders or depression are included, these challenges become larger. For example, AIDS dementia complex is a major concern because it is usually observed in the later stages of the disease. It is reportedly seen in up to 50 percent of patients prior to death (Ances and Ellis, 2007). When individuals with this complex are on a regular and effective antiretroviral regimen, a new complication arises: establishing the resources needed to care for them as they age with the associated complications.

Currently there are no robust guidelines on the interaction of HIV and therapies with the older generation medications used to treat mental health disorders commonly available in SSA. In fact, for patients with epilepsy, there are noted drug interactions between the older, commonly used antiepileptic medications, such as phenobarbitone, carbamazepine, and phenytoin, and certain newer antiretroviral regimens (Kakooza-Mwesige, 2009). Kakooza-Mwesige noted that this means patients need to be monitored—especially those on medications such as antiepileptic drugs—for both short- and long-term toxicities. The question, Kakooza-Mwesige noted, is always “do we have the available resources?” Studying, understanding, and learning to cope with the complex overlay of HIV/AIDS and MNS disorders is going to be increasingly critical to care in SSA over the next decade. Patrick Kelley, director of the Board on Global Health at the IOM, noted, “We have about 4 million people under antiretroviral therapy, yet there are approximately 30 million infected people and 2 to 3 million new infections in Africa each year.” At the same time, MNS disorders will likely grow as well. “We know scientifically, at the molecular level, that HIV affects brain cells much earlier than we anticipated in the past,” noted Elly Katabira, associate professor at Makerere University School of Medicine. This means that HIV prevention is extremely important from an MNS point of view. It also means that the success with antiretroviral therapy is raising a new policy

issue—it is not only reducing HIV transmission, but it is also affecting the prevalence or manifestations of the mental complications that can show up in persons living with HIV/AIDS.

With the growing numbers of infected people, Kelley noted, “Over the next decade to 15 years, there is going to be a tremendous increase in demand for HIV therapy. I suspect some money will follow this demand because there is a lot of compassion around the world in addressing the problem.” That, as panelists would discuss later, offers a window of hope to improve patients’ lives by attacking both problems at the same time. Leveraging the established HIV/AIDS infrastructure will provide new opportunities to raise awareness of associated MNS disorders, improve diagnosis, and establish better treatments and care.

The Disease Burden of Malaria

Malaria is endemic in much of Africa, and illness due to malaria is one of the most common reasons for a visit to a health facility. For example, in Uganda 25 to 40 percent of outpatient visits are due to malaria, with 20 percent of health facility admittances due to the infectious disease. Malaria is responsible for nearly 14 percent of deaths in Uganda (Roll Back Malaria et al., 2005). Most malaria cases are uncomplicated—the disease is not normally fatal if diagnosed early and treated properly. However, all too often treatment is delayed, and the patient may deteriorate to the point where the disease becomes severe, with high risks of complications and death.

A related complication is cerebral malaria, which occurs when parasitized blood cells are found in the capillaries of an infected individual’s brain. Although most complications are transient and resolve within 6 months, about 10 to 24 percent of people who survive cerebral malaria go on to have neurological and cognitive sequelae—impaired vision, impaired hearing, impaired speech, recurrent seizures, gait disturbances, and various degrees of paralysis, noted Daniel Kyabayinze, clinical epidemiologist and research officer at Malaria Consortium Africa. However, Silberberg reported data that suggest an even greater impact on children, noting that between 50 and 75 percent of children with cerebral malaria survive, but not without consequences. He described a study that showed 32 percent of individuals had complications at a 71-week follow-up, including behavioral disturbances, epilepsy, gross motor delay, language delay, or hemiparesis (weakness on one side of the body) (Potchen et al.,

2010). Furthermore, children between the ages of 6 months and 5 years old are at a higher risk for cerebral malaria, as are travelers from non-malaria areas, pregnant women, individuals with sickle cell disease, and people with HIV/AIDS (WHO, 2006b).

Treatment for malaria complications is often delayed in part because malaria is so common in the region. For example, Kyabayinze estimates that every year there are one to two episodes of malaria for every person living in Uganda. Because so many people have had it, often more than once, many people think of malaria as a simple disease. Sub-Saharan countries with endemic malaria have an added risk for MNS disorders because the disorder may stem from delayed treatment for what appears to be just malaria. However, with improved focus on malaria prevention and awareness among healthcare providers about associated MNS complications, the portion of the burden of MNS disease arising from malaria could potentially decline.

Substance Use Disorders in Sub-Saharan Africa

Unfortunately, comprehensive statistics on substance use (alcohol and drugs) disorders in SSA is limited. For example, unrecorded alcohol consumption is estimated to be about half the amount consumed in Africa and in East Africa—specifically, more than 90 percent of alcohol consumed, according to some estimates, is unrecorded (WHO, 2004). This is due in part because in many African countries alcohol is produced at the local level in villages and homes. These traditional forms of alcohol are usually poorly monitored for quality and strength, and in most countries it is possible to find examples of health consequences related to harmful impurities and adulterants.

Alcohol, tobacco, and drug-related problems are becoming an increasing concern in the African region. In addition, many African countries are used as transit points for illicit drug trade and these drugs are finding their way into local populations, adding to the indigenous problems associated with cannabis consumption. Furthermore, there is an increased demand for home-brewed beer or locally distilled liquor. Most countries have no national policies on alcohol or tobacco; consequently, their advertising, distribution, and sale are largely uncontrolled (Okasha, 2002). Increasing poverty, natural disasters, wars, and other forms of violence and social unrest are major causes of growing psychosocial problems, which include alcohol and drug abuse, prostitution, street chil-

dren, child abuse, and domestic violence. These often lead to greater substance use disorders.

Aside from the direct effects of alcohol on a person’s physical and mental health, studies from Nigeria, South Africa, and Uganda have shown strong associations between domestic violence and alcohol use (Jewkes et al., 2002; Koenig et al., 2003; Obot, 2000). In South Africa levels of alcohol were particularly high for transport- and violence-related injuries with, for example, 46 percent of patients with transport-related injuries in Cape Town having levels above the legal limit for driving (0.05g/100ml), and 73 percent of patients with violence-related injuries in Port Elizabeth. In addition, alcohol abuse has been linked to risky sexual behavior and increased likelihood of contracting HIV. Alcohol use is also strongly associated with depression.

A large number of medical conditions are seen in individuals who suffer from addiction, including lung and cardiovascular disease, stroke, cancer, and mental disorders. Drug abuse has deleterious impacts throughout the body. Furthermore, a third of new AIDS cases are a result of infection through the injection of drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine.

STIGMA AND HUMAN RIGHTS

The Stigma Problem: Breaking the Silence

Throughout Europe and the United States, MNS disorders such as substance use, seizure disorders, and psychological conditions carry social stigmas. SSA is no different, and MNS sufferers face substantial stigma within their communities (Baskind and Birbeck, 2005; Satcher, 1999). To people unfamiliar with the scientific underpinnings of MNS disorders, simple behavioral changes such as confusion can be seen as madness; seizures can be seen as possession by evil or angry spirits.

The stigma of MNS disorders impacts all aspects of treatment and care of the patient—from individuals in the community, through providers in healthcare facilities, even into policies being developed by governments. It affects people in many ways, most tragically by often preventing individuals from receiving treatment. Katabira of Makerere University discussed the stigma that individuals with epilepsy receive. “Epilepsy is treatable,” he said. “But it is treatable because you know there are drugs available. The ordinary man in the village may have entirely different beliefs about epilepsy. He may relate it to a curse in the fam-

ily.” However, because epilepsy is not often associated with a medical condition, it may never occur to the individual’s family that they should seek medical treatment. Instead, the families may hide the patient for fear of what the village community would think. Even when services are available in the community, they are often not used out of fear or ignorance, he said.

The healthcare community is not immune to these issues. Practitioners hold their own beliefs and, as Katabira said, their prejudices and associations are often in direct contradiction to their training. This is not the case for specialists who have received significant training. Rather, he suggested, there are few specialists in the community setting. “The majority of our healthcare workers have had very little training,” he continued. “When they see a person with an epilepsy fit, their natural instincts tend to come on first, and these may actually deter the patients from actually seeking professional health services.”

Workshop participants discussed the need to end the silence about MNS disorders, noting the importance of education—educating the communities and health workers in each local village that these MNS disorders are treatable medical conditions that should be devoid of shame and fear of, or for, the victim. Through the collection of data, instituting education, advocacy, and healthcare policies that include MNS disorders can be tools to end the silence and treat the suffering. This will be discussed in greater detail in Chapter 4 of this summary.

Human Rights Violations

There is a history of human rights violations of persons with mental disorders across the world, but today the most disturbing examples are found in developing countries (Patel et al., 2006). Images displayed at the workshop by Patel were first released by Time magazine in 2003. These pictures depict atrocious conditions of care for people with mental disorders in hospitals in Southeast Asia. On further exploration, Patel and colleagues discovered these images were tragically representative of conditions for mentally disturbed patients that extended to intellectually challenged disabled children and women who were dispersed by war. Images of despair depicted the harsh lives of persons with MNS disorders in Africa, stripping them of their dignity. Often, these conditions are deemed necessary by family members to keep the person “safe.” For example, there was an image of a young man who was put in a cage that his parents constructed to keep him safe when they went to work every

morning because no one else was home with him. The WHO website shows a woman with a mental illness standing on a street in an African village, begging while being shackled to a log of wood, with the shackles in place more to keep her safe than any other reason.

Two models were discussed that could serve as ways the provider community could improve care and reduce stigma and mistreatment of individuals with MNS disorders. The South African Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) is one model. TAC was established to demand respect and dignity for people living with HIV/AIDS. Launched in 1998 on Human Rights day, this 10-year-old action campaign called for access to treatments and demanded dignity for people living with HIV/AIDS, first in South Africa, then in the world. Inspired by TAC, the Movement for Global Mental Health was launched on October 10, 2008. Its goals are to achieve the call for action to scale up evidence-based services and strengthen human rights protection for people with mental and neurological disorders. This movement hopes to emulate the success of TAC and bring together individuals and institutions who share a vision of human rights protection for all those with MNS disorders.