3

Framing Health Disparities

Lori Dorfman, Dr.P.H.

Director, Berkeley Media Studies Group

Lori Dorfman is the director of the Berkeley Media Studies Group (BMSG), a project of the Public Health Institute. The Public Health Institute is an independent, nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting health, well-being, and quality of life for people throughout California, across the nation, and around the world. BMSG studies news coverage of public health issues, provides professional education for journalists, and conducts media advocacy training for community groups and public health advocates. It is from this perspective that Dorfman delivered her comments. She began her presentation by describing why BMSG focuses much of its research on the news. The goal of public health is to improve the health of populations and to do this by improving the conditions in which they live. The news is crucial to public health, according to Dorfman, because policy makers pay attention to the news and policy makers are making key decisions about whether the environments surrounding the public support health or foster disease. Therefore, if public health practitioners want to get the attention of policy makers, they need to understand how public health issues are portrayed in the news and be able to interest reporters in public health stories. By studying the news, BMSG can determine how public health issues are portrayed, including what part of the story is being told and what part is being missed.

FRAMING PUBLIC HEALTH ISSUES

According to Dorfman, framing public health issues is complicated and difficult in part because it involves the issue of race, one of the most difficult topics to discuss in the United States. Although there are no easy answers or magic words, understanding how these issues are framed is a good place to start.

To begin, a definition of the concept of “framing” itself is needed. “Framing” is an abstract idea, one studied by individuals from many disciplines, including social psychology, cognitive linguistics, sociology, economics, and political science. Scholars from these fields teach that frames are the conceptual bedrock for understanding anything. Frames help people extract meaning from all sorts of texts: words, pictures, events, or interactions.1 That is, people are able to interpret words, images, actions, and text of any kind only because their brains fit those texts into a conceptual system that gives them order and meaning. Just a few cues—say, a word or an image—trigger whole frames that determine how people understand the matter at hand. Frames, Dorfman says, are structures that people’s minds bring to text to make sense of it. Frames are mental structures that help people understand the world.

At the same time that people have frames operating from within, there are cues from the environment that also influence people’s understanding of the world. Framing is therefore an interaction with the ideas in people’s minds and the cues that they encounter. The external cues can activate people’s internal assumptions and values. Recent research in the field of cognitive linguistics indicates that some assumptions, values, explanations, or stories are more easily triggered than others.

To illustrate, Dorfman used the example of looking up a new word in the dictionary. After one goes to the trouble to look up and really learn the new word, it suddenly seems as if one sees it everywhere. It is a paradox of sorts: the word was there all along, but the person’s brain did not recognize it until after he or she learned it. As Walter Lippmann put it, “For the most part we do not first see, then define, we define first and then see” (Lippmann, 1965).

Dorfman used a second example to illustrate how people’s brains react to cues in the environment (Figure 3-1). With a few external cues, people think that they know what is said in the first box. In other words, a person’s brain fills in the blanks. The second box, however, which shows the actual text, indicates that the person’s interpretation would have been wrong. This

|

1 |

There is a broad literature on framing. See, for example, the work of Lakoff (1996) and Hall (1997). For studies of how public health issues are framed in news coverage, see http://www.bmsg.org/; for studies of how people interpret frames, see http://www.culturallogic.com/ and http://frameworksinstitute.org/. |

FIGURE 3-1 Example of the importance of external or environmental cues.

SOURCE: Adapted from BMSG (2005).

is how framing works: frames fill in the blanks, giving meaning to what people see. Human minds are so efficient at filling in the blanks that the process is unconscious and unquestioned, which can be a problem when the answer is wrong, as it was in this case.

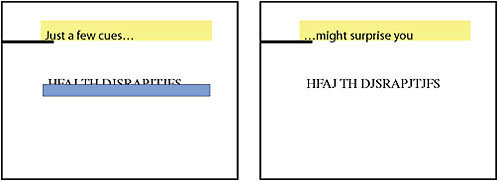

Another example, from the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press in 1999 (Figure 3-2), shows how two variations of a question from the same public opinion poll garner different responses depending on how the question is asked. Essentially, the poll asked the same thing, but because the questions are expressed slightly differently, the percentages of people choosing the different answers were dramatically different.

One explanation for the discrepancy in the poll results could be that the word “government” has been demonized in the United States and is therefore dismissed out of hand by most people. If this is true, this is a major problem for the field of public health because public health must rely on the government as the solution in many instances. A second explanation is that the second question is more descriptive and concrete than the first question. Either way, the words used matter, as they made a difference in how people responded.

A key concept here is that the brain interprets external stimuli—words, images, interactions—on the basis of what it already knows. It means that the more that an idea is repeated, the easier it is for people to “see.” In addition, information that contradicts well-formed and strongly held ideas and beliefs is hard for people to integrate. Therefore, reframing needs to take place, by which people learn to tell new stories and adopt new ideas.

THE DEFAULT FRAME: RUGGED INDIVIDUALISM AND PERSONAL RESPONSIBILITY

The framing process happens whenever people interpret cues of any kind. It is critical, then, to talk about cultural cues in the United States and how those cues influence society. Small cues from words or pictures can trigger whole sets of ideas in the minds of audiences, who fill in the rest of the story. Thus, from a public health perspective, the question is: are we triggering the right frame, one that will help people understand that environments affect the population’s health? If not, it will be hard to help people see the importance of the policies that can help rectify health disparities.

It is also critical to understand what is wrong with the typical, frequent cues that people receive and how they perpetuate ideas about what is possible and how things change. In American society, people operate with a default frame that elevates the notion of personal responsibility above institutional accountability. This is in large part because in American culture the stories that people tell themselves about themselves in various forms of media and other venues are typically hero stories, such as the Horatio Alger myth emphasizing the idea that if people try hard enough or work hard enough, anything can be accomplished. A commonly applied metaphor for this idea is “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps.” Even computers “boot themselves up”—that is, they start from nothing to become something—indicating how deeply this metaphor runs in society.

Dorfman pointed out that the flip side of this metaphor is that if a person fails, it is his or her own fault. These two ideas are parts of the same whole; one cannot exist without the other. The challenge facing public health advocates in the United States today is that this is the unspoken starting point for any conversation about health disparities or any other health problem. Any cues about health will be interpreted against this backdrop, unless an alternative is provided. This means that, for example, delivering simple statistics about health disparities is likely to engender a response such as, “Well, that’s too bad. Those people should try harder,” rather than a response that points to the conditions surrounding individuals. Although this might seem inconsistent with Dr. Brown’s earlier statement about the importance of data, the point is that having good data is necessary but not sufficient in altering frames.

Americans do have alternative stories that illustrate the “collective good,” but those stories are harder to trigger. For example, for most people, the story of civil rights in the 1950s and 1960s is understood almost exclusively as a hero story. Of course, there were important heroes in the civil rights movement. People need to hear more about heroes like Rosa Parks and the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. However, Dorfman suggests,

should we not also hear just as often about the institutions and organizations that nurtured and supported those heroes? Why is the role of the Highlander Center, as described by Mindy Fullilove, not as well known as the name of Rosa Parks?

An example of a story about the collective good is the popular culture idea of a barn raising, in which the entire community comes together for the day and works together to literally frame and build a barn. Together, people build what none of them could do alone. However, this is an image that is based in the 19th century. People have few readily available images of what it means to work together for the collective good today.

The fundamental problem, according to Dorfman, is that the stories that reinforce individualism are the ones that are heard the most, and they are the ones that are the most easily evoked and the most frequently cued. Therefore, to address health disparities, new stories, a new language or a “second language” for public health, are needed (Wallack and Lawrence, 2005). These new stories can help people see that along with personal responsibility, environments shape health.

THE ROLE OF THE MEDIA

The media plays an important role in setting the agenda around public health issues for policy makers. They help frame the debate, which can influence the choices that are made about how health disparities may be rectified.

Media researchers have identified two types of news stories, the episodic story and the thematic story (Iyengar, 1991). Dorfman compared the difference between episodic and thematic stories to the difference between a portrait and a landscape. Most news stories are portraits, or episodic stories, that focus narrowly on people or events rather than on the context surrounding those people or events. About 80 percent of television news stories and most newspaper stories are episodic. In the news, people see, over and over again, stories that emphasize individuals or specific events without much attention to the broader context of the story.

In experiments, when researchers ask viewers who have seen episodic news to identify who has responsibility for causing or fixing a problem, no matter what the topic is, viewers who have seen stories framed as portraits will respond in ways that tend to blame the victim. This is consistent with the default frame and consistent with what social psychologists call the “fundamental attribution error.” This tendency to attribute responsibility for solving a problem to the individual rather than institutions or other aspects of the environment surrounding individuals is a problem for public health, in that the types of policies designed to improve public health usually address changing the conditions surrounding people.

The good news is that the other 20 percent of news stories are framed thematically, more like landscapes. In this case, the news story still generally depicts a central person or event, but there is some context around that person or event. Viewers respond differently to this type of story. When viewers see stories framed as landscapes or thematic stories and are then asked in experiments about who has the responsibility for causing or fixing the problem depicted, they tend to answer in ways that include institutions or government as part of the solution. The inclusion of even a little more context in a 2-minute television news story can trigger a different understanding by viewers. This is a hopeful finding for public health professionals who must rely on governmental strategies to solve health problems.

Unfortunately, however, when the protagonist in these thematic or landscape stories is African American, this effect no longer holds. Rather, viewers go back to “blaming the victim.” This finding is extremely disheartening and evidence of the extraordinary difficulty that this country has when it comes to race. This is an enormous problem that simple prescriptions about storytelling cannot easily overcome. Other research on how the public understands—or does not understand—health disparities reinforces the challenges that researchers and the public health community face in reframing health disparities. Researchers studying how inequality is understood found the following, for example (Grady and Aubrun, 2008):

-

Operating from the default frame, the average person sees disparate health outcomes as evidence of the natural order of things rather than as evidence of a problem that needs to be rectified.

-

The American culture’s emphasis on individual responsibility blinds people to the systemic factors that affect population health.

-

Such thinking reinforces us-versus-them divisions that distance groups from one another (and, if the default frame is not challenged, can be reinforced whenever public health statistics are disaggregated by race or socioeconomic status).

-

Guilt, denial, and “compassion fatigue” can undermine support for taking action on health disparities.

STEPS TOWARD REFRAMING HEALTH DISPARITIES

Dorfman suggested that to alter frames, public health advocates should consider the following questions:

-

What cues are we giving?

-

What stories are we telling?

-

What values do these stories activate or trigger?

-

What actions are we taking?

In other words, according to Dorfman, reframing is more about what public health advocates do than what they say.

In the earlier example from the civil rights movement, the community organizing that was ignited by Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat on a Birmingham bus one Thursday afternoon was about actions as much as words.

In a current example from public health, advocates and funders concerned about obesity and related health problems are acting to change the built environment so it encourages daily activity, such as walking to work. Major structural changes, however, require significant resources. In the case of changes to roads and sidewalks, these resources can be found in the federal transportation legislation to be authorized by the U.S. Congress in 2010. These funders are therefore providing public health groups with the resources needed to work on the transportation sector as a solution to the problem of obesity. They are also providing resources to reformers in the transportation sector to work with public health. Their collective actions will help reframe transportation so it is understood and acted upon as a public health issue (Bell and Cohen, 2009).

In conclusion, Dorfman reiterated that actions influence reframing as much as how things are talked about. That is, the message is never first; rather, the reframers must know what needs to be changed. Public health professionals need to be clear about how they are going to make the changes and why change needs to occur. Beyond words, Dorfman says, actions are needed. What organizational practices within public health itself can be instituted to establish mechanisms for rectifying health inequities? Health disparities are about inequities, as well as about race and class, and both of these are very difficult to talk about in the context of the default frame. It is therefore important to be clear about what the goal is, what people are trying to do, and how this will be accomplished.

Dorfman summarized by reminding the workshop participants about the quotation in the front of every Institute of Medicine publication, by Goethe: “Knowing is not enough. We must apply. Willing is not enough. We must do.”

REFERENCES

Bell, J., and L. Cohen. 2009. The Transportation Prescription: Bold New Ideas for Healthy, Equitable Transportation Reform in America. Convergence Partnership. Available at: http://www.convergencepartnership.org. Accessed August 11, 2009.

BMSG (Berkeley Media Studies Group). 2005. Committee for Economic Development. Framing the Economic Benefits of Investments in Early Childhood Development. Available at: http://www.bmsg.org/documents/CEDDorfmanECEFrames.pdf.

Grady, J., and A. Aubrun. 2008. Provoking thought, changing talk: discussing inequality. In “You can get there from here….” An occasional paper series from the Social Equity and Opportunity Forum, College of Urban and Public Affairs at Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Hall, S. 1997. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (Culture, Media and Identities Series). Edition 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Iyengar, S. 1991. Is Anyone Responsible? How Television Frames Political Issues. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, G. 1996. Moral Politics: What Conservatives Know that Liberals Don’t. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Lippmann, W. 1965. Public Opinion. New York: The Free Press. P. 54.

Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. 1999. Third Party Chances Limited. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center for the People and the Press.

Wallack, L., and R. Lawrence. 2005. Talking about public health: developing America’s “second language.” American Journal of Public Health 95:567–570.