11

What Are the Societal Implications of Citizen Mapping and Mapping Citizens?

The popularity of Web mapping sites such as Google Maps, Google Earth, and Microsoft Virtual Earth has exploded in recent years. Particularly in wealthier parts of the world, these sites have become a central part of daily life (the “next utility”) as they are used to navigate to places of work, pleasure, and commerce, and to allow citizens to increase their knowledge of the world. Not only do people want to receive information from these sites; they increasingly want to share it as well. Sites, such as Wikimapia.org, OpenStreetMap.org, MapAction.org, and Flickr.com are empowering millions of citizens to create a global patchwork of geographical information. This information is already serving society in many ways—assisting in local tourism and community planning, disaster response (e.g., citizen maps of Southern California fires), humanitarian aid, habitat restoration, public health monitoring, and personal assessments of environmental impacts. This citizen mapping “workforce” is largely untrained, under no authority, and the mapping is often done for no obvious reward (Goodchild, 2007).

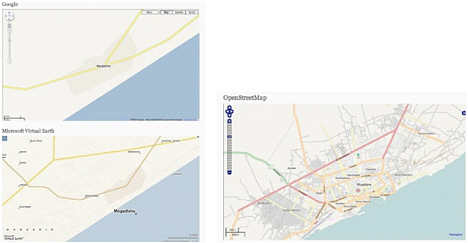

Goodchild (2007) terms this recent phenomenon “volunteered geographic information” (VGI), wherein a private citizen participates in the creation, assembly, and dissemination of geographical information on the Web. The information is “volunteered” primarily by adding a geographical identifier (known also as a geotag) to a Wikipedia article, photograph, or video, or by adding one’s own geographical data to an interactive, Web-based map, often by marking locations of certain features that are of importance, places where various events have occurred, or places where an individual has been or would like to go (Figure 11.1). For those with more advanced computing skills, Google Earth and other virtual globes are providing ways for citizen mappers (known also as neogeographers) to develop their own mapping applications, such as geoGreeting, which create greeting messages in Google Maps spelled out in satellite images of real buildings from all over the world that happen to be shaped as letters when viewed from above. VGI can be a boon, for example, to international development and humanitarian relief organizations, which can supply these organizations with the most up-to-date detailed data (Figure 11.2).

The power of such Web sites to increase the efficiency, pleasure, and safety of our lives is becoming increasingly apparent. However, the issue of individual privacy has arisen just as quickly as the technologies themselves. Privacy is about limiting access to facts about an individual, including gender, marital status, income, and social security number, in order to protect against intrusion, appropriation, or breach of confidence. The issue of privacy is heightened when locational information is involved. Most people do not expect ultimate privacy while at their places of work, but they expect it in their homes. Location can also present privacy concerns in a dynamic sense, both directly (“I don’t want people to know my current location in space and time”) and indirectly (“I don’t want certain things associated with me because of my current location in space and time, such as my presence at an adult video store”) (Curry, 1998; Armstrong and Ruggles, 2005; Bertino et al., 2008).

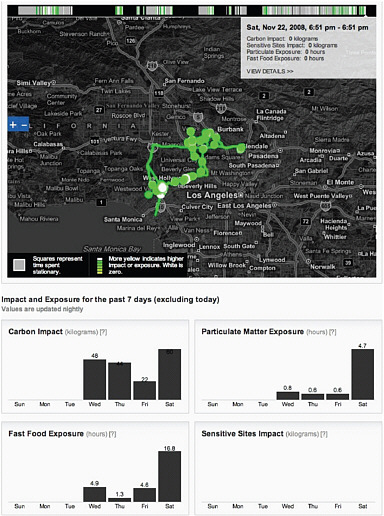

FIGURE 11.1 Example of a VGI project from the University of California, Los Angeles Center for Embedded Networked Sensing, where private citizens use their mobile phones to explore and share the impact of the local environment on their lives and vice versa (e.g., Cuff et al., 2008). The map and graphs show demonstration outputs from the Personal Environmental Impact Report, an online service that interacts with a user’s mobile phone to provide an environmental “scorecard” that tracks possible exposure to carbon emissions, fast food, and particulates, as well as impact on sensitive sites throughout the Los Angeles metropolitan area. In this sense, the citizens themselves become the environmental sensors. The service is accompanied by a privacy policy for participants that explains the risks of collecting and sharing location information and how data and information are being controlled. SOURCE: peir.cens.ucla. edu (accessed January 20, 2010).

FIGURE 11.2 The map on the left shows part of the street network in Mogadishu, Somalia, available in Google Earth (top) and Microsoft Virtual Earth (bottom). The map on the right showing the same region, but with streets supplied by VGI in OpenStreetMap. org, provides information of considerable use to international development and humanitarian relief organizations. SOURCE: www.developmentseed.org/tags/mapping (accessed January 20, 2010).

THE ROLE OF THE GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENCES

Most citizen mapping involves the use of the Internet. Some view the Internet as a technology that is abolishing the significance of geographical location and distance (e.g., Cairncross, 1997), but there is much evidence to the contrary. As noted in The Economist (2003):

It was naive to imagine that the global reach of the Internet would make geography irrelevant. Wireline and wireless technologies have bound the virtual and physical worlds closer than ever…. Actually, geography is far from dead. Although it is often helpful to think of the Internet as a parallel digital universe, or an omnipresent “cloud,” its users live in the real world where limitations of geography still apply. And these limitations extend online. Finding information relevant to a particular place, or the location associated with a specific piece of information, is not always easy.

It follows that geographical context is relevant to any discussion of the nature and implications of VGI and its enabling technologies. VGI is often made possible through the use of geographically enabled “smartphones,” personal digital assistants or PDAs (i.e., handheld computers), digital cameras, and vehicle navigation systems. These devices are equipped with ready-made maps and Global Positioning System receivers, further empowered by a location-based service (LBS). LBS is an information service provided by a device that knows where it is and then uses that knowledge to select, transform, and modify the information that it returns to the user. Hence the device can supply driving or walking directions to businesses, restaurants, and automated teller machines; find other users in close proximity; or even send alerts, such as when a user is approaching a traffic jam or accident. Peter Batty (a former chief technology officer of two leading geographic information system [GIS] companies) has recently introduced whereyougonnabe.com, which takes this kind of networking one step further by allowing users to tell their friends where and when they plan to be located in the future.

There is growing concern that the proliferation of technologies and the production of detailed, micro-level spatial data are outpacing our ability to protect information about individuals. The same techniques that allow Web users to create mashups by linking infor-

mation around common geographical locations also allow government agencies to build massive databases on individuals and their behaviors (e.g., NRC, 2008a) and make it possible for the private sector to keep track of a wealth of personal information. The practitioners of the emerging field of “collective intelligence” acknowledge that, if misused, locational information on individuals “could create an Orwellian future on a level Big Brother could only dream of ” (Markoff, 2008). The geographical sciences are of central importance to this challenge because, as noted by the NRC Committee on Confidentiality Issues Arising from the Integration of Remotely Sensed and Self-Identifying Data (NRC, 2007b): “precise information about spatial location is almost perfectly identifying: if one knows where someone lives, one is likely to know the person’s identity.”

The social issues raised by these tools are more urgent today than two decades ago, and there is every indication that the urgency will grow in the future. The geographical sciences are central to understanding the nature and implication of new forms of data acquisition. Geographical scientists have the background and training to bring to bear language, guiding principles, and theoretical constructs that are relevant to locational and mapping technologies. They offer research methods that can facilitate the exploration, analysis, synthesis, and presentation of data about citizen mapping activities and their social implications. The concern of geographical scientists with place and context is particularly important, as the study of citizen mapping and locational privacy is not just about acquiring and using locational data. It is about understanding how data are used and viewed in particular places, and by particular communities. Geographical scientists wonder not only about the “where” of the present, but the implications of “where” for the future, and how spatial behaviors will change under the circumstances of traffic congestion, crisis (emergency evacuation from natural disaster, terrorist attack; e.g., Torrens, 2007), or even mass euphoria (musical concerts or a political rally). Bringing these concerns to bear on citizen mapping initiatives and locational data collection is essential to the effort to understand the social implications of geographical practices.

The responsibility of the geographical sciences to confront this issue becomes clear when one considers that geographical research itself may infringe upon the personal privacy rights of individuals. Box 11.1 describes one present-day example. The following research questions provide examples of issues that would be particularly productive to investigate.

|

BOX 11.1 Tracking Residents in Bath, England ‘There’s a storm brewing in [the English town of] Bath. Today’s Guardian newspaper reports that residents are being tracked without their knowledge. The tracking is part of a University of Bath project that’s called Cityware [a research collaboration of computer scientists and psychologists]. It’s designed to study how people move around cities. Here’s how it works. Cityware researchers have installed scanners at secret locations around Bath. Those scanners capture bluetooth radio signals. Bluetooth is a short-range wireless technology. It’s found in mobile phones, laptops, even digital cameras. Now if somebody in Bath moves by a scanner with his or her bluetooth device turned on, then Cityware can pinpoint that person’s whereabouts. The results are stored in a database. Researchers and city officials contend that they cannot identify anyone personally from the data collected, but the scanners don’t let Bluetooth users KNOW that they are being watched, and some have called ‘foul….’ [transcripted from the radio broadcast Public Radio International’s The World, as broadcast on July 21, 2008, available also at www.theworld.org/?q=node/19600]. The researchers of this study maintain that the purpose of Cityware is not to track individuals, but to study the aggregate behavior of city dwellers as a whole, while also allowing those individuals to find their way around the city, participate in interactive citywide games and cultural activities, and access a host of information services while working, socializing, or relaxing (Lewis, 2008). The human rights “watchdog” group Privacy International has countered that “it would not take much adjustment to make this [Cityware] system an ubiquitous surveillance infrastructure over which we have no control” (Lewis, 2008). |

RESEARCH SUBQUESTIONS

What are the characteristics of the producers of VGI and how should we evaluate the content and quality of what they have produced?

Producers of VGI are themselves subjects of much needed research (e.g., who volunteers and why, what are their geographical and social characteristics, what kind of locational information are they interested in volunteering?). Initial studies have shown that people

volunteer information in the belief that it will be open, accessible, and free, and may even be of significant help. Some are also motivated by self-promotion, the desire to fill in gaps in data, or merely to connect easily to friends, relatives, and colleagues (Goodchild, 2008). Geographical methods for exploration, analysis, synthesis, and classification of spatial data (e.g., multiple-criteria evaluation methods in the context of decision-support systems as developed by Jankowski et al. [2008], as well as various landscape visualization techniques and participatory three-dimensional models) are needed to shed light on who is involved in VGI and what they are doing. A study that mapped participation and correlated it with multiple socioeconomic variables might, for example, reveal that most VGI in a certain region comes from upscale residential neighborhoods, and could further understanding of the social, political, and technological factors that affect how geographical data are developed, accessed, and interpreted (Elwood, 2007). Research is needed to define the limits of VGI in this context and to shed light on the social psychology of the producers of VGI.

Institutional review boards (IRBs) have emerged in recent years to protect the rights of human subjects in research projects, and yet there is wide variability in their capacity to apply and disseminate confidential research (Lane, 2003). Many IRBs are quite conservative vis-à-vis locational privacy, making it difficult for researchers to work with tracking data. This orientation could be a major impediment to useful research. Sieber (2004) has suggested some innovative ways in which IRBs could improve researchers’ understanding of confidentiality issues, including how best to interpret, adapt, and apply nondisclosure techniques, but the challenge of developing ways to contront locational privacy issues remains (NRC, 2007b).

Turning to the evaluation of content and quality, VGI has been termed asserted information, to contrast it with the authority of traditional sources. While mapping agencies have developed elaborate mechanisms for quality control and assessment, the quality of VGI remains very much an open research issue (although in other areas of volunteered information, such as Wikipedia, some preliminary research results are now available, e.g., Read, 2006). Researchers working on this topic need to develop ways for educated citizens to produce not only volunteered geographical information but also volunteered geographical analysis. Given existing perspectives and methods, the geographical sciences could develop rubrics to assess and evaluate the quality of VGI (i.e., both the validity and accuracy of VGIs, as well as the quality of any metadata) and the accuracy of resulting maps. For example, Flanagin and Metzger (2008) discuss (1) emerging analyses and rubrics for geographical training and education of novices by experts; (2) assessment of the notoriety of systems (such as the level of trust users now have in Wikipedia, Google Earth, Citizendium, etc.); and (3) development of algorithms that reveal (via IP address) the source of content or compute the “reputation” of an author’s entry as measured by its longevity. Researchers could investigate the thematic limits of VGI (i.e., the kinds of geographical information that is best acquired in this way, rather than by scholars or government authorities) and its ethics (what protections are needed for individual privacy, and the limits on what people should be able to report about others?).

In what ways does participation in VGI have the unintended effect of increasing the digital divide?

Discussions of neogeography and of what can be achieved today by citizen mappers rarely include the issue of the digital divide—the sharp contrast between those with effective access to digital technology and those with limited or no access. Although most people in high-income countries are used to the power of Google Earth, the vast majority of the world’s citizens have no access to either the Internet or personal computers. Moreover the divide is growing, as certain groups acquire more and more technology and others continue with nothing. Since the proliferation of VGI could exacerbate the digital divide, it is important to understand better whether, and where, this might happen (e.g., in contrast to Figure 11.2, some parts of the world still don’t yet “show up” because people there cannot contribute information).

In the free-for-all atmosphere of the Internet, it is easy to forget the impediments to accessing geographical data and tools. GIS software can be expensive and far beyond the resources of many. In other cases, governments actively seek to keep geographical technologies out of the reach of groups of people. We need to understand how spatial knowledge is shaped

by identity, power, and socioeconomic status, and how spatial data handling is socially and politically mediated (Harvey et al., 2005). Research in this vein will help us understand how we need to alter community planning paradigms and decision-making practices in order to more fully realize the potential of VGI, without exacerbating the digital divide.

Sui’s (2008) call for a focus on equity and privacy in studies of VGI raises critical questions about the motivations and incentives for people to engage in VGI. For example, to what extent does the digital divide influence citizen participation? He asks whether the “wikification process” may enlarge disparities in society by allowing “the favored few to exploit the mediocre many,” as opposed to narrowing the digital divide, thereby producing “digital dividends” for a broader community (Sui, 2008). Addressing these issues will require collaboration with the open-source software community, as it (1) already understands the relationships between security, privacy, functionality and freedom (Peterson, 2008), (2) is beginning to understand and implement the principle of developing software that is both citizen controlled, yet privacy oriented (Peterson, 2008), and (3) is often committed to closing the digital divide.

What and where are the most significant threats to human privacy as presented by emerging geographical technologies and how can we design technologies to provide protection?

Even as geographical technologies are enabling positive aspects of citizen mapping such as VGI, they also appear to be among those opening society up to a new kind of surveillance in the mapping of citizens (Pickles, 1991; Monmonier, 2002). As an example, Elwood (2008) cites www.RottenNeighbor.com, which allows people to post the location and perceived offenses of their neighbors. Richards (2008) reports that various shopping centers in the United Kingdom are now using the cell phone signals of customers to monitor which stores people visit and how long they stay there. Yang et al. (2008) propose an activity recognition system that would track people’s movements throughout their home in order to help them perform forgotten tasks (such as taking medicine), choose which rooms to play music in, or diagnose a slow Internet connection. Such a system makes use of the existing Wi-Fi connections and Internet protocols already at play within a home network of PCs, printers, phones, TVs, and networked stereos. However, as highlighted by Claburn (2008), such systems also raise privacy issues. How will datasets be protected? Who will have access to them? And what will prevent them from being stolen or even subpoenaed? These questions point to the need for research into how new forms of knowledge production and access may affect privacy and facilitate new forms of surveillance (Elwood, 2008).

The core assumption of the LBS industry is that corporations will own and control locational information about their individual customers. This assumption leads to different technical challenges and research questions for situations involving both the public and private sectors (Raper et al., 2007). Researchers need to take up the challenge of developing the synthetic datasets that will limit “the risk of identification while providing broader access and maintaining most of the scientific value of the data” (NRC, 2007b: 2). We thus support the conclusions of the National Research Council that “various new technical procedures involving transforming data or creating synthetic datasets show promise for limiting the risk of identification while providing broader access and maintaining most of the scientific value of the data. However, these procedures have not been sufficiently studied to realistically determine their usefulness” (NRC, 2007b: 2).

Collaborations between academics and industry scientists can lead to the development of effective algorithms for “geographic encryption,” also known as “geographic masking” (Kwan et al., 2004). There is a need for different ways of suppressing, resampling, or multiplying by random noise certain records in a geographical database (e.g., Armstrong et al., 1999), perturbing the underlying microdata rather than perturbing the database cells themselves (Lane, 2003), and developing other geomasking techniques for both continuous and categorical variables that can be applied locally (to a subset of records with a high disclosure risk) rather than globally (e.g., VanWey et al., 2005; Zimmerman et al., 2007). These approaches are supported by the NRC (2007b), which recommends that data stewards develop licensing agreements to provide increased access to linked social-spatial datasets that include confidential information. Bertino et al. (2008)

recommend further that development of standards for geographical data security and advanced geographical data protection is now critical. In addition, the work of Zandbergen (2008), which characterizes the capabilities of reverse geocoding (i.e., deriving an address from a position, rather than vice versa) using a range of different network analysis methods, offers a promising example of how research on this topic could make advances over the next 10 years.

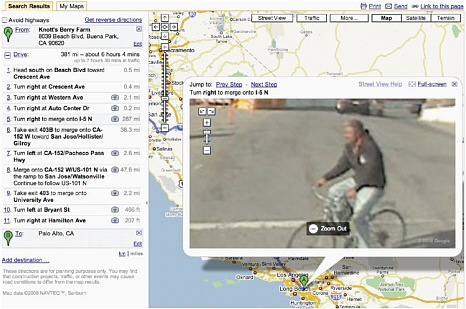

The urgent need for work on privacy protections for locational data becomes clear when one considers that, despite efforts to ensure the privacy of personal information (e.g., protection of social security, credit card, and driver’s license numbers), no explicit regulation currently protects locational privacy in the United States. It is important to note that data availability and concerns about privacy vary by culture. For example, in the United States, Google has responded to privacy concerns by testing and gradually implementing a face-blurring algorithm for its Street View service (Figure 11.3), but Canada has enacted an identity protection law, requiring Google to blur not only faces, but also license plates. Bitouk et al. (2008) have developed software that goes beyond the simple blurring of a face in a photograph to “swapping” the features in a face with random features from a library of faces (such as a Flickr library). The result is a composite photograph that changes the identity of the person in order to further protect his or her privacy.

Over the next 10 years, geographical scientists should continue research on responsible locational data release formats, while working to develop codes of practice for LBS use. The work of Onsrud (2003) and Solove and Rothenberg (2003) shows that there is great potential in collaborations with legal scholars to identify principles governing the dissemination of personal geographical information in various contexts. This will allow researchers to estimate the social benefits and costs of information dissemination, and to identify potential conflicts.

FIGURE 11.3 Implementation of the face-blurring algorithm in Google Street View. SOURCE: maps.google.com/help/maps/street-view (accessed January 20, 2010).

SUMMARY

The recent and stunning emergence of citizens as both the sources and subjects of mapping has serious implications for individual privacy and many related societal issues, as millions worldwide continue to create a global patchwork of geographical information. The geographical sciences are central to promoting understanding of the nature and responsible use of these new forms of data acquisition and dissemination.