6

How Does Where People Live Affect Their Health?

Health has always been a fundamental social concern, but apprehension over health issues has escalated in recent years in the wake of extensive media coverage of disease outbreaks, the rapid spread of infectious diseases around the world, growing evidence of the health impacts of exposure to the by-products of industrialization, and anxieties about the availability and affordability of health care. Because environmental factors play a fundamental role in shaping human health, locational issues are of central importance to addressing health questions. A variety of place-based influences affect health, including physical circumstances (e.g. altitude, temperature regimes, and pollutants), social context (e.g., social networks, access to care, perception of risk behaviors), and economic conditions (e.g., quality of nutrition, access to health insurance). Because locational influences are myriad and constantly shifting, and because people themselves are moving around at unprecedented rates (Chapter 7), understanding the health impacts of where people live is one of the most challenging, yet important, contemporary geographical problems.

The influence of location on health is clear even at the global scale. The best way to reduce the worldwide burden of disease may be to provide individuals with ready access to clean water, adequate nutrition, and rudimentary sanitation, yet the availability of these “big three” basic needs differs greatly from place to place. People’s access to immunization is perhaps the next most important variable in the health picture, yet access to immunization often depends on social circumstances and the distribution of health care facilities.

Much has been learned in the past about geographical influences on health through mapping the spread of diseases, access to care, and the treatment and prevention of illness. Coming more fully to terms with the impacts of location on human health, however, requires documenting, modeling, and predicting human health outcomes at individual- to population-level scales, while accounting for

-

Human mobility (e.g., daily, weekly, seasonal, life course),

-

Socioeconomic circumstance (e.g., income status, age, education, gender),

-

Behavioral risk factors (e.g., smoking, drinking, drugs, diet),

-

Changing environment (e.g., climate change, industrial development, urban expansion),

-

Time course of disease (e.g., cancer latency, induction period),

-

Genetics (e.g., determinants of predisposition to disease).

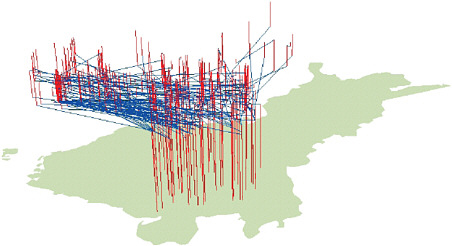

Addressing some of the major health challenges of the 21st century requires developing increasingly sophisticated theories, methods, visualizations, and tools that can help account for the intersecting impacts of these six variables in different locations (Figure 6.1).

The global resurgence of vector-borne diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, yellow fever, and Lyme disease (Gubler, 1998) highlights the need to enhance understanding of the geographical dimensions of disease occurrence and spread. Malaria alone kills an

FIGURE 6.1 A three-dimensional geographical visualization of the residential mobility of 1,000 cases of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) in southeastern Finland, distinguishing movers (blue) from nonmovers (red). The vertical lines represent periods of stability and the blue lines link the origins and destinations of the moves. Sabel et al. (2003) identified a birthplace cluster of the disease in southeast Finland—the first example of a significant ALS cluster being identified worldwide. This part of Finland has suffered from significant industrial pollution, and heavy metals are present in the environment. To determine whether these heavy metals may be implicated in the etiology of ALS, Sabel et al. (2009) used the detailed migration histories of the cases and controls to explore differences between movers and nonmovers. The results demonstrated that moving away from the area seems to be protective, meaning that the environment has a role to play in the disease etiology. SOURCE: Unpublished figure courtesy of Paul Boyle.

estimated 700,000 to 2.7 million people each year (Patz and Olson, 2006). The increasing movement of people and products is raising the specter of the spread of one of the most potent malaria vectors, Anopheles gambiae, from Africa to South America and Southeast Asia. Such an event occurred in the 1930s when A. gambiae was accidentally introduced to Brazil. A vigorous campaign to identify breeding areas and eradicate larvae was required during the 1930s and 1940s to avert a near disaster (Parmakelis et al., 2008). More sophisticated analyses of locational influences on malaria are vital to several current international initiatives aimed at halting the spread of malaria, including the Multilateral Initiative on Malaria, which is part of the United Nations Children’s Fund, United Nations Development Programme, World Bank, and World Health Organization Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases.1

ROLE OF THE GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENCES

Traditionally, epidemiologists allocate risk for specific diseases such as cancer to specific causes, including willingness to participate in high-risk behaviors (e.g., smoking), nutritional status, age, genetic predisposition, and gene–environment interactions. Studies are usually based on experiments (e.g., case-control studies, cohort studies) aimed at evaluating whether a specific factor is associated with an increased risk of disease. Although useful, this approach often fails to take into account the range of locational influences that affect diseases or the temporal and spatial complexities that arise from disease latency and individual mobility through the life course. The geographical sciences have a role to play in addressing such matters. Building from an early focus on disease patterns, the geographical sciences are devoting attention to the development of models and visualizations that provide insight into space-time influences on health and disease (Jacquez et al., 2005a,b; Meliker et al., 2005). These models and visualizations

|

1 |

See www.mimalaria.org (accessed January 20, 2010). |

help geographical scientists account for the impacts of exposure to potentially hazardous substances in different places (Meliker and Jacquez, 2007). Geographical scientists are also exploring ways of using remote sensing (satellite data and hyperspectral imagery) in the study of disease location and spread (Goovaerts et al., 2005; Avruskin et al., 2008).

The geographical sciences add at least four dimensions to the investigation of disease incidence and response, and of conditions such as drug addiction (Thomas et al., 2008). First, they provide a series of techniques suited to the detection of patterns and anomalies in the incidence of disease, and to their interpretation in terms of disease-spreading and disease-causing mechanisms. From the earliest successes achieved by John Snow in unraveling the etiology of cholera (Johnson, 2006) to modern techniques for detecting statistical significance in apparent clusters (O’Sullivan and Unwin, 2003), a vast amount of pure and applied research has gone into the examination of health and disease patterns, and their connection to other circumstances and processes in the human–environment system (Cromley and McLafferty, 2002; Waller and Gotway, 2004; Koch, 2005). Second, geographical science tools allow researchers to ask questions about the factors present in an area that correlate with disease outcomes, whether as causes or as statistical correlates. Geographic information systems (GIS) have proved valuable in this regard because they support a range of multivariate analyses and can be used to analyze the impacts of factors at different scales. Third, geographical scientists have developed spatially explicit models of disease spread that incorporate concepts such as distance and connectivity directly into the models, often in the form of cellular automata2 (Schiff, 2008) or as agent-based models (Maguire et al., 2005). Finally, the concern of the geographical sciences with location promotes consideration of access to health care. When facing conditions such as heart attacks, the distance between the patient and the emergency room and the ability to get to the emergency room quickly can literally be the difference between life and death. Geographical scientists have found dramatic impacts of differentially located health care facilities, at scales that range from the global to the local (e.g., O’Meara et al., 2009), and they have developed a range of techniques for optimizing the location of facilities to achieve desirable goals (e.g., Rushton, 2003).

Much health research makes use of statistical techniques to make general conclusions from samples of laboratory animals or patients. When these experiments are controlled, by choosing random samples and giving them identical treatments, the conditions conform precisely to the assumptions made in standard statistical tests. In such cases significance levels can be determined, and results generalized to the populations from which the samples were randomly drawn. However, in research focused on actual fine-scale geographical patterns rather than controlled conditions, these assumptions are rarely valid (O’Sullivan and Unwin, 2003). Analysis at the national level often uses health statistics aggregated to the county or even state level—units of analysis that have their origins in previous centuries, vary enormously in size, and average or smooth out much of the actual variation that occurs at smaller scales. These statistical issues provide examples of the substantial problems confronting health researchers that the technical arsenal of the geographical sciences can help resolve. The following questions illustrate the types of research that allow the geographical sciences to contribute to the development of a multidisciplinary synthesis, which is needed to tackle major health issues in the years to come.

RESEARCH SUBQUESTIONS

How do diseases respond to changes in ecosystems and climate?

Spatial distributions of diseases are seldom uniform, and understanding the reasons for their heterogeneity can lead to valuable insights. As our ability to conduct spatial and temporal analysis has improved, so has our ability to characterize both sides of the disease equation—the genetics of diseases themselves and human risk factors. Advances in spatial and temporal analysis are also facilitating efforts to respond to changes in the human–environment system.

On the genetic side, new insights into how and why diseases emerge and sometimes lead to pandemics such

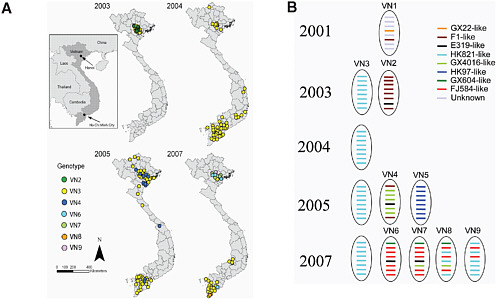

as HIV and influenza can be achieved by coupling the study of molecular and spatial analysis. One example of this type of inquiry is a study on H5N1 avian influenza that analyzes genetic change using a spatial approach (Figure 6.2). As part of the study, a spatiotemporal influenza genotype database was built and integrated with ecosystems factors using GIS. The diffusion of different H5N1 genotypes and mutations that are related to virulence is being tracked, and the impacts of human–environment ecosystem factors (e.g., human population distributions, farming systems, land use, climate) on H5N1 viral evolution are being measured using a spatial analytical approach called ecological niche modeling. Similar efforts for other viruses can help identify the human–environment ecosystems in which viruses change.

Climate change can have substantial impacts in the area of health, affecting, for example, the emergence and resurgence of vector-borne diseases (those diseases such as malaria or West Nile virus that are transmitted to humans, animals, or plants via an insect or other organism). A recent National Research Council report states that “nearly half of the world’s population is infected with at least one type of vector-borne pathogen” (NRC, 2008c). With climate change potentially expanding the spatial reach of vector-borne diseases by increasing flooding, altering precipitation patterns, and raising temperatures, there is a need for research that explores the link between climate change and such diseases.

A robust earth observing system that monitors key climate variables is critical to predicting future disease outbreaks. Anyamba et al. (2009) propose using satellite measurements to examine the linkage between climate variability and the outbreak of Rift Valley fever in the Horn of Africa. Their work examines the relationship between outbreaks of the disease, which affect animals and humans, and the El Niño/Southern Oscillation. They conclude that satellite observations can be used to map climate changes, which in turn can be used to predict the location of outbreaks. Like Rift Valley fever, outbreaks of malaria, yellow fever, or

FIGURE 6.2 (A) Geographical distribution of the genotypes identified for 142 H5N1 viruses isolated in Vietnam from 2003 to 2007, with the viral genotype of each H5N1 isolate mapped chronologically to show the time of genotype isolation in different regions of Vietnam. (B) Emerging H5N1 genotypes from introduction and reassortment in Vietnam from 2001 to 2007, showing the genetic change of each H5N1 virus segment using a different color corresponding to its precursor virus—a sort of family tree for the virus. SOURCE: Michael Emch, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Geography. Used with permission.

dengue fever are not just public health events; they are environmental, economic, and ecological as well. The geographical approach adopted in the Rift Valley fever study could advance understanding of the relationship between climate change and vector-borne disease outbreaks more broadly.

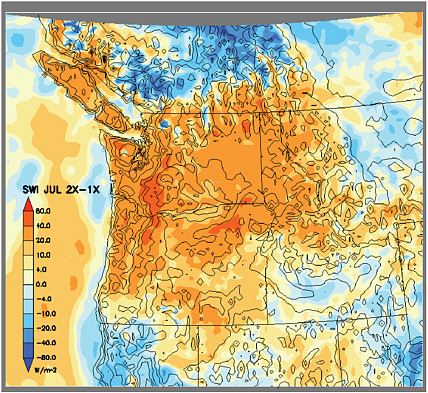

Climate change could also affect the risk to humans of noninfectious diseases such as melanoma. Melanoma is known to be caused by exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Ethnicity is a risk factor (epidermal melanin is protective), as is location (altitude, latitude), occupation (indoor, outdoor), and individual behaviors (e.g., outdoor lifestyle). Climate models predict highly spatially heterogeneous changes in UV radiation as a function of atmospheric CO2 doubling (Figure 6.3). Future research is needed on the impact of different climate change scenarios on melanoma incidence using the time-dependent locations of individuals coupled with models of climate change and of melanoma risk.

How do disparities in geographical access to health care affect health and well-being?

The locations, number, and quality of health care providers differ from place to place, and services may not be available in places where they are most needed. Access to health care is not simply a matter of measuring distance to health facilities; access is affected by socioeconomic status, cultural and social norms, and transportation networks. In a study of access to gov-

FIGURE 6.3 Simulated changes in July incident solar radiation over the Pacific Northwest expressed as the difference between doubled and present atmospheric CO2 concentrations (2×-1×). SWI: incoming solar radiation (W/m2). The model was configured with a horizontal grid spacing of 15 km and 23 layers in the vertical. Solid black lines indicate U.S. state borders and elevation. SOURCE: Courtesy of Steve Hostetler and Justin Holman.

ernment health services in Kenya, for example, Noor et al. (2006) show that a transportation model adjusted for actual use patterns and competition between health facilities provided a much better indicator of access to health care than did a model focused solely on distance. Their example illustrates that understanding the locational circumstances that create inequalities in access to health care is a critical piece of the health picture.

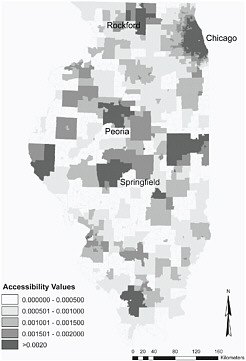

Studies analyzing geographical inequalities in health care access should build on increasingly detailed work on this topic. For example, Luo and Wang (2003) have developed an index of spatial accessibility as a way of analyzing the local supply of primary health services in relation to local demand. Their method was used to analyze spatial access to primary care in Illinois and its relationship to late-stage cancer (Wang et al., 2008). Not surprisingly, in Illinois, as in much of the United States, rural areas are characterized by lower levels of spatial access to primary care than urban areas (Figure 6.4). But why are some rural communities much more disadvantaged than others? Geographical scientists such as Cutchin (1997) have taken up this question, looking at the specific attributes of rural places that tend to attract primary-care physicians and encourage them to stay. Additional work in this vein can provide policy makers and community planners with much needed insight into ways of addressing the problem of rural health care access.

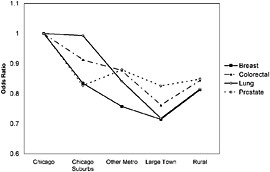

Another example of the promise of spatially explicit studies of health care access comes from ongoing research on whether cancer patients living in communities with poor access to primary health care have a higher-than-average risk of late-stage diagnosis (cancer diagnosed after it has spread to distant tissues or organs; Figure 6.5). The researchers conducting the study undertook multilevel analyses of the associations between late-stage risk, individual demographic variables, and contextual variables, describing socioeconomic characteristics of places and their spatial access to primary care (McLafferty and Wang, 2009). Their research showed that, in Chicago, the high risk of late diagnosis among cancer patients largely reflects the high concentration of vulnerable people living in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods. Outside Chicago, poor spatial access to primary care significantly heightens the risk of late diagnosis among breast and colorectal patients, supporting the findings of geographical scientists in other contexts (Rushton et al., 2004). McLaffery and Wang also identify poor health outcomes in a dense urban setting where spatial access to care is quite high, according to GIS-based measures.

These findings highlight the need for research investigating the connections between population vulnerability, place vulnerability (Chapter 3), and access to health care. Among the most important topics to investigate are effects of time-space constraints on the use of primary health care by low-income urban residents

FIGURE 6.4 Spatial access to primary care in Illinois by ZIP code based on the 2-Stage Floating Catchment Area method. Light tones indicate poor spatial access to primary care. The map was created as part of a study examining the combined effects of spatial access and socioeconomic factors on breast cancer diagnosis. The results showed that poor geographical access to primary health care had significantly increased the risk of late diagnosis. The study also showed that spatial access to primary health care was more important than similar access to mammography. SOURCE: Wang et al. (2008).

FIGURE 6.5 Variation in risk of late-stage cancer diagnosis for the four major cancers in Illinois. The figure shows that risk is highest for cancer patients living in Chicago. The odds of late diagnosis decrease away from Chicago, reaching their lowest levels among patients living in large towns (defined here as towns with populations ranging from 10,000 to 50,000 and not located in metropolitan areas). This figure does not control for age or race, but the study looked at the impacts of both and found that the rural-urban gradient remained consistent for breast, colorectal, and lung cancers, but disappeared for prostate cancer. SOURCE: McLafferty and Wang (2009).

and geographical variations in the quality of health care. There is also much to be gained from comparative analyses of the spatial dimensions of health care access in different parts of the world and for different types of health challenges (e.g., heart disease, HIV/AIDS, vector-borne diseases).

How are social factors affecting the spread of diseases, such as HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa?

HIV/AIDS is the leading cause of death in Sub-Saharan Africa, which remains the epicenter of the epidemic, accounting for 67 percent of all people living with HIV worldwide and 72 percent of all AIDS-related deaths (UNAIDS, 2008). In southern Africa, the worst-affected region, national adult prevalence exceeds 15 percent in seven countries. Women account for nearly 60 percent of HIV infections in Sub-Saharan Africa, and young women represent 67 percent of all new cases of HIV among people ages 15-24 living in developing countries (UNAIDS, 2008).

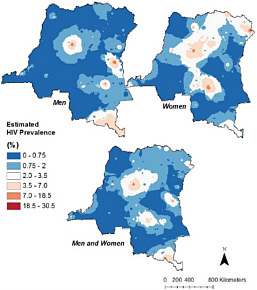

It is well established that spatial variability is a key factor in understanding HIV/AIDS; geographical concentrations of HIV/AIDS are found even in many countries with very low HIV prevalence. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, for example, Messina et al. (In review; Figure 6.6) documented a high degree of spatial variability in HIV/AIDS cases and found that the distribution of the disease was influenced by such social factors as sexual practices, socioeconomic status, and access to transportation. Future work in this vein could describe the spatial distribution of genetic subtypes of the HIV/AIDS virus, which in turn could facilitate the effort to understand not only where imported cases originate, but where and how those cases evolve from earlier strains. Work on the impacts of socioeconomic status on the distribution of

FIGURE 6.6 HIV distribution in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, showing differential patterns for men and women. A geographically based, population-representative sampling scheme allowed Michael Emch and his colleagues to construct this visualization, which was then used to examine the impacts of social factors on the distribution of HIV/AIDS. Not surprisingly, the study found that social factors are the most important drivers of the distribution of the disease. SOURCE: Michael Emch, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Geography. Used with permission.

cholera in Bangladesh confirms the value of this type of approach (Emch et al., 2010).

There is a long tradition of work on this subject in the geographical sciences (Gould, 1993), but the range of contextual influences needs to be expanded. It is becoming clear that more attention needs to be paid to the influence of attitudes toward sex, female empowerment, and economic inequities on the spread of diseases (Kalipeni et al., 2007). Additional work focused on developing and analyzing data on the spatial distributions of HIV/AIDS and relevant social circumstances can improve understanding of the range of influences on the vulnerability of different people in different places (Kalipeni et al., 2007, 2008).

Globalization and migration are also changing sexual practices in Africa (Ampofo, 2001; Spronk, 2005). As a result of globalization, the media, including cinema, television, and the Internet, provide Africans with new sexual imagery, and undermine traditional boundaries of sexuality and sexual expression. Further research is needed on where these changes are having the greatest impacts, and how they are affecting the spread of HIV/AIDS. Work in this vein could also provide a more detailed understanding of the role of migrant labor on the diffusion of HIV/AIDS (Bassett and Mhloyi, 1991; Jochelson et al., 1991; Hunt, 1996).

Governance is another social factor affecting the spread of HIV/AIDS in Africa and elsewhere. Relatively little attention has been paid to the effects of civil wars and political instability on HIV/AIDS. As victims of armed conflict and as refugees (or internally displaced persons), women and children are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence and abuse. Warring factions often use rape as an expression of violence and revenge against their enemies (Kalipeni and Oppong, 1998). In refugee camps, women and girls remain subjects of sexual coercion; separated from their families and living as internally displaced persons or refugees, survival compels many individuals to engage in transactional sex with other refugees or the host population (Spiegel and Nankoe, 2004). The volatile mix of refugees, soldiers, desperate women with children, and the chaos associated with war facilitates HIV/AIDS spread, but how this plays out in different places is not well understood.

The efforts of multilateral organizations, such as UNAIDS, have focused on assisting governments to deal with the challenge of HIV/AIDS rather than evaluating how the apparatus of government—whether democratic, autocratic, or chaotic—affects HIV/AIDS spread. Yet government leadership, particularly good governance, expressed by effective administration of international aid for HIV/AIDS control, and public health programs including antiretroviral access, influence the success or failure of HIV/AIDS control efforts, as do policies that address poverty and social inequalities. Including such matters in a broadened effort to look at contextual influences on the geographical spread of HIV/AIDS can enhance understanding of how and why disease diffusion patterns are different from place to place.

SUMMARY

The geographical sciences have a role to play in advancing understanding of spatial variations in the spread of disease, access to care, and the treatment and prevention of illness. The tools and approaches of the geographical sciences can provide insights into locational factors affecting health, and they can illuminate important contextual influences on the diffusion of diseases. A major initiative to build upon and expand work in the geographical sciences on health matters would benefit efforts to combat disease and promote human well-being.