8

How Is Economic Globalization Affecting Inequality?

We live in an unequal world in which descriptors of global inequality—especially inequalities in income—abound. “[T]he world’s richest 500 individuals have a combined income greater than that of the poorest 416 million … 2.5 billion people [are] living on less than $2 a day” (Watkins et al., 2005: 18). Researchers and policy makers continue to debate how, and at what scale, inequality trends are changing, but, by any measure, the disparities between rich and poor are striking (Firebaugh, 2003; Milanovic, 2005; The Economist, 2006; Held and Kaya, 2007; Lobao et al., 2007). The recent past has also seen rapid economic globalization—characterized by the supranational spatial integration of economies and societies (Stiglitz, 2002). Globalization has intensified flows of goods, finance, people, and political/cultural interactions all across our planet (Mittelman, 2002; Dicken, 2007). Understanding the nature of, and linkages between, globalization and inequality is crucial because disparities abound in access to needs such as shelter, land, food and clean water, sustainable livelihoods, technology, and information. Inequalities in all of these realms pose challenges to human security and environmental sustainability.

Much of the research on the link between globalization and inequality has focused on the global scale—looking at inequality between countries using aggregate economic indicators such as gross domestic product per capita (sometimes weighted by national population). These measures of global inequality are limited because they implicitly assume that within-country distributions of income are perfectly equal (Milanovic, 2005). Comparisons of inequality across individuals in the global population, and across a broader range of measures, regardless of national boundaries, are much rarer, but are increasingly possible and necessary (Milanovic, 2005). Beyond the need for improved measures of global inequality, we are currently witnessing a historic change in patterns of inequality, termed by Firebaugh (2003) as the “inequality transition.” Since the 1980s, evidence suggests that inequalities have increased more rapidly within countries than between them, heralding the reversal of increasing between-country inequality—a trend that began with the Industrial Revolution (Milanovic, 2005; Held and Kaya, 2007).

Because it may seem counterintuitive that subnational inequality would grow in an era of globalization, this finding points to the importance of research on scale differences in inequality patterns, and on the spatial impacts of specific aspects of economic globalization, so that we can better understand how globalizing processes influence inequality—where and for whom (Kanbur and Venables, 2007). Addressing this problem requires research aimed at identifying how distributional mechanisms within markets and governance arrangements are shaping inequality across geographical scales and differentially distributed populations (see Lobao et al., 2007).

The timing of the recent shift in inequality patterns (the early 1980s) corresponds with the rise of new forms of economic globalization that have transformed spatial relationships around the globe. Expanding transportation and communication networks, trade liberalization, reorganization of financial structures, and the rise of new

regional trade agreements have been redefining flows of commodities, investments, labor, and political power across the globe (Murray, 2006; Dicken, 2007). In the process, the “where and who” of the winners and losers of globalization are changing, as is the traditional role of the state in economic governance. The state is no longer the only, or even the primary, actor in economic processes, because markets are now global, regional, and local as much as they are national (O’Loughlin et al., 2004). A key research challenge going forward, then, is to move beyond a focus on individual states and identify the relationships between globalization and shifting patterns of inequality at varying scales (Held and Kaya, 2007).

ROLE OF THE GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENCES

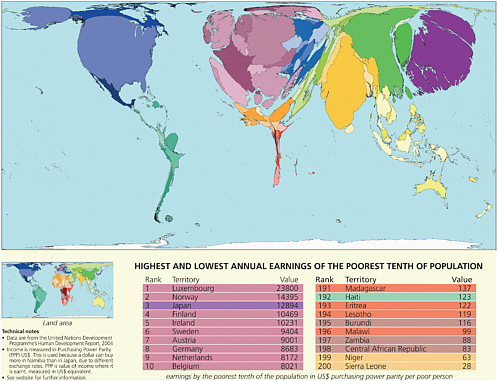

Research in the geographical sciences can help identify the patterns and processes producing inequality across the world—within states and at local levels. Although sociology takes inequality to be a central problem, Lobao et al. (2007) argue that too much sociological research on inequality still operates at the national scale and entails questionable geographical assumptions about both the causes and patterns of inequality. These scholars argue for “the systematic incorporation of spatial factors into theory and research on inequalities” (Tickameyer, 2000: 811) and for research that builds multiscale models and draws on spatially referenced data. Geographical scientists are at the forefront of this research, undertaking projects aimed at representing and analyzing the intersections between the spatial and social dimensions of inequality. For example, geographical research is providing innovative cartographic representations of inequality that shed light on the nature and significance of patterns of inequality (Figure 8.1).

Research in what has been termed the “new economic geography” is currently analyzing the spatial character of inequality by building structural models of the relations between economies of scale, transport costs, geographical remoteness from markets, and biophysical resource endowments (Krugman, 1993; Redding and Venables, 2004). The 2009 World Development Report adopts this frame of analysis to argue that three geographical dimensions of the global economy must be transformed to reduce inequality. The report argues that these reductions will result from (1) a greater concentration of economic activity (density), (2) a reduction in the friction of distance (i.e., increasing the mobility of goods, capital, and labor), and (3) diminished divisions between places as a result of borders and differences in language and regulations (World Bank, 2009: 7). Research in the geographical sciences extends the new economic geography (see Part I, Box 1), positing the fundamental importance of place-based influences on economic developments. It follows that policy makers need to focus more attention on local contextual influences, a point highlighted by Kates and Dasgupta (2007: 16749). Along the same lines, Sachs (2006: 73) notes that “policy makers and analysts should be sensitive to geographical, political and cultural conditions that may each play a role (in producing poverty).”

In their efforts to understand uneven development within and across places, geographical scientists have developed a body of work focused on the spatially variable operation of processes producing inequality in places characterized by different systems of macroeconomic regulation, different welfare regimes, different social divisions of labor (between paid and unpaid work, for example), and different consumption and distribution practices (Jones and Kodras, 1990; Smith, 1990; Kodras and Jones, 1991; Perrons, 2001). Research in this vein, which has been undertaken by geographically oriented researchers in demography, geography, economics, and political science, has shown that inequality emerges from multiple processes operating simultaneously at a range of spatial scales, including unequal global distributions of returns to production and work at sites along international production and consumption chains; regional trade agreements that limit national sovereignty on environmental and labor protections; and the presence of race and gender discrimination in different places (Nagar et al., 2002). Their findings are of relevance to debates about the economic and inequality impacts of market liberalization (see generally Firebaugh, 2003; Milanovic, 2005; Dicken, 2007; Kanbur and Venables, 2007).1

FIGURE 8.1 This cartogram resizes national territories by the earnings of the poorest 10th living in each territory, focusing attention on comparative issues of importance for research on space, scale, and inequality. By visualizing the relative scope of inequality across major regions, questions are raised about the causes of similarly deep inequality in both Latin America and Africa vis-à-vis the countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Striking spatial patterns such as these point to the potential importance of common social and economic histories that situate each of these regions in particular ways within global divisions of labor, commerce, politics, and cultural flows. SOURCE: Worldmapper. Copyright 2006 SASI Group (University of Sheffield) and Mark Newman (University of Michigan).

Systematic comparisons of subnational inequality and its causes across a range of countries, and in the context of global processes, could move the research agenda forward. Prior research has compared patterns and processes of within-country inequality for Britain, the United States, South Africa, and the former Soviet Union to determine how different economic structures, institutional arrangements and processes of discrimination (apartheid, class, gender and race) are associated with distinct patterns of spatial and social inequality (Smith, 1987). Smith’s comparative research is now 20 years old, however, and we lack an adequate understanding of how recent developments are changing economic, social and political landscapes as a result of global financial instability, new global trade regimes, and environmental instability in the wake of the transition from socialist to capitalist, globalized economies in some parts of the world (cf. Mykhenko and Swain, 2010, who provide a contemporary example of research on the links between territorial inequality, post-socialist transition, and the importation of foreign capital).

Studies by Dicken (2007) and Leichenko and O’Brien (2008) in particular highlight the value of focusing on the specific mechanisms of globalization and the role they play in shaping who and where the winners and losers of globalization are found. Their work points to the importance of analyzing the inequality outcomes of international trade treaties, global environmental regulations, global regulations on investments and the activities of transnational corporations, as well as spatial variations in labor standards and laws. Yet to date, the inequality impacts of these seismic shifts in global institutional and societal processes have not been systematically compared as they play out between and within countries around the globe (Murray, 2006; Dicken, 2007). In the next 10 years, researchers will have access to decennial census data and household income surveys (from many countries) that will allow them to represent and understand the spatial and scalar dimensions of inequality—both between and within countries during a period that will likely be characterized by intensifying globalization and economic instability. Against this backdrop, the investigation of the following research questions would be particularly productive.

RESEARCH SUBQUESTIONS

What patterns of inequality are emerging at the subnational scale?

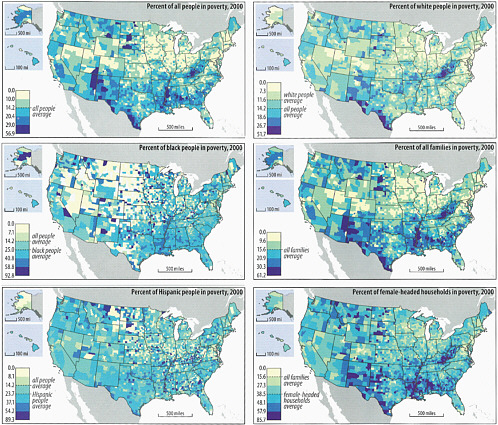

A long tradition of geographical work focuses on developing visualizations of spatial patterns that can facilitate deeper understanding of sociospatial processes. Cartographic representations of inequality across countries and scales reveal current patterns of winners and losers in the face of globalization processes. For example, Glasmeier’s Atlas of Poverty in America (2005) identifies regions in distress: Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta, areas where indigenous people are concentrated, and much of the U.S.-Mexico border region. Drawing on state, county, and metro-scale socioeconomic data across four decades, the Atlas represents the social and spatial dimensions of poverty within each region and identifies vulnerable populations of children, women-headed households, and minorities. This detailed mapping of poverty over time suggests relationships between places and people, raising analytical questions about the intersections of gender, household structure, race/ethnicity, place, and poverty in different parts of the United States (Figure 8.2). This within-country representation of variables associated with poverty provides a model for the type of comparative spatial analyses that are needed across countries.

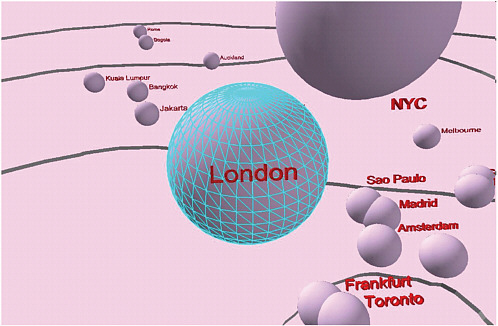

New geographical visualization techniques also offer insights into linkages between inequality and the multiple consequences of globalization. Professor Danny Dorling’s team at the University of Sheffield is developing geovisualizations of social spatial structures (at a range of scales) that allow the research community to pose new questions about how people’s life chances are distributed and how are they changing (Figure 8.3).2 This research group has also developed a series of virtual atlases using flow lines and multidimensional scaling to visualize global city networks (see Figure 8.3). These visualizations demonstrate how fast Internet connectivity for some people and places changes their possibilities for engaging globalization processes, with different implications for places that remain relatively disconnected.

The digital divide in Internet connectivity could influence the ways in which places are understood in the future, as volunteer geographical information becomes increasingly central to the collection of georeferenced data about our world. Those cities and countries that are relatively underresourced in technologies, relevant education, and Internet connectivity will be poorly represented in terms of data accuracy or the range of information available (elaborated further in Chapter 11 of this report). In the future, teams of researchers could use geovisualizations to model uncertainty in inequality patterns that may result from distinct scenarios of globalization. By representing the possible impacts of global connectivity and isolation, they could inform policy decisions about the implications of connectivity and isolation for access to key resources (land, water, energy, etc.), engagement with the global economy, and environmental alteration at the subnational level (Smith, 1987; Murray, 2006; Moseley and Gray, 2008).

Where and how does market liberalization exacerbate or reduce spatial inequalities?

Market liberalization has been a central facet of globalization since the 1980s. Market liberalization

|

2 |

See www.sasi.group.shef.ac.uk/ (accessed January 20, 2010). |

FIGURE 8.2 A map series showing the spatial distributions of different populations in poverty in the United States. SOURCE: Glasmeier (2005).

entails the global integration of trade and capital markets through free trade agreements and changes in national trade and financial regulations such as tariff barriers and capital controls. These liberalization processes, along with exuberant lending, overconfidence in monetary policy (as an effective control on money and credit supplies), and floating currencies, brought both high economic growth rates and considerable economic turbulence, with dramatically different impacts for different people and places (as in the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s, the Asian financial crisis of the 1990s, the global financial crisis of 2008; Krugman, 2000). Market liberalization has also led to a reworking and intensification of networks of connectivity between many cities; an expanding role for transnational corporations in global production and consumption networks; and the large-scale privatization, and international ownership, of telecommunications, transport systems, and primary resource extraction in low-income countries (Dicken, 2003).

In recent years, geographical research has yielded important insights into the social and spatial trade-offs

FIGURE 8.3 City connection map that demonstrates how “close” other cities are to London in a virtual space of relationships based entirely on connection values. SOURCE: Social and Spatial Inequalities. Used with permission.

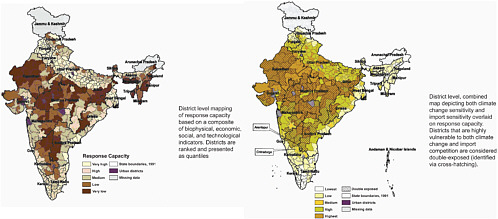

between trade liberalization and inequality (including research focused on economic growth, environmental change, and human vulnerability). For example, Leichenko and O’Brien (2008) have exposed patterns of advantage and harm in agricultural communities in India in the face of twinned processes of market liberalization and climate change. Their work begins from the premise that the inequality effects of global processes have distinct spatial and social expressions (see also Sachs, 2006; Kates and Dasgupta, 2007). Drawing together data on climate impacts on crop yields, changes in plant pollination and competition, and human vulnerability to climate change, Leichenko and O’Brien (2008) constructed maps revealing the regions that are most vulnerable to predicted climate changes across the country (see also the discussion of this study in Chapter 3). A geographic information system analysis of the relationship between that map and patterns of agricultural export advantage, import sensitivity, and the resilience of farmers to socioeconomic change allowed them to identify places across India that are “double exposed” to climate change and trade liberalization and places that are less exposed, and therefore are likely to be less vulnerable in the face of these processes (Figure 8.4).

Similar methodologies and tools can be employed to analyze the changing geography of inequality in the face of the twin impacts of market liberalization and climate change (Liverman and Vilas, 2006). Research in this vein will require the construction of integrated datasets from existing national and international sources at a range of spatial scales, including production and trade data, household income surveys, national census data, and United Nations and World Bank data (see Ravallion, 2001; Redding and Venables, 2004). These new datasets can be employed to produce targeted sectoral and regional analyses of understudied economic sectors (e.g., industry and energy systems in the tropics), which in turn can pave the way for research exploring the ways in which a variety of key economic sectors are influenced by global trade and

FIGURE 8.4 Maps depicting district-level response capacity and sensitivities to climate change and import competition. SOURCE: Leichenko and O’Brien (2008).

capital flows in ways that produce shifting landscapes of production, consumption, and vulnerability (Liverman, 2008).

How are poverty, wealth, and consumption interrelated across space and at multiple geographical scales?

Differences in wealth and poverty are often not solely the result of local circumstances; they are produced by relationships that link far-flung places. Geographical scientists investigate how spatial relationships shape inequality, such as the relationships between production in low-income countries and rich-country consumption, or the inequality effects of deploying agricultural lands for domestic foodstuffs or for export crops. They have developed conceptual and analytical tools for tracing the networks of production, consumption, and exchange that link people across world markets and for identifying the processes through which wealth and poverty are explicitly linked. Of particular significance is work on (1) production chains—linked sequences of place-based functions where each stage adds value to the commodity (Dicken, 2007); (2) consumption chains—links between consumption and the conditions of production (Hartwick, 1998); and (3) global commodity chains, which expose prices, and the geographical distribution of value, at each node along the production and marketing trajectory of a specific commodity (Gereffi and Korzeniewicz, 1994; Leslie and Reimer, 1999).

Geographical research on commodity chains is enchancing understanding of the ways in which inequality is reworked through production and consumption linkages. For example, Nepstad et al. (2005) have traced how consumers in high-income countries shape the nature of agricultural commodity chains through an examination of the globalization of soy and beef industries based in the Brazilian Amazon. They developed a network analysis that connects growing fears of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE or mad cow disease) in ration-fed beef in the United States and Europe with increasing demand for grass-fed beef from the Amazon. Their work demonstrates how conditions of production are reworked by pressures from consumers demanding both improved environmental stewardship and better social conditions for workers. Their study reveals that pressures from lender and consumer organizations to reduce the negative socioecological impacts of production are leading to the environmental and social certification of beef, timber, and soybeans. Additional geographical research building on this conceptual and empirical foundation could further elucidate the nature of commodity networks and show how certification

programs rework inequality (e.g., Mutersbaugh, 2003; Tovar et al., 2005; Klooster, 2006).

Bassett’s (2008, 2010) empirical research on cotton commodity chains linking West African agriculture to global markets provides further evidence that poverty and consumption are linked across space and scale (Moseley and Gray, 2008). Bassett explores how patterns of inequality across space and scale are shaped by the linkage of West African cotton farmers’ incomes to market liberalization; relationships between producers, workers, and consumers; and interactions between ecological and social systems. He found that African cotton growers are relatively marginalized in negotiations over prices for seed cotton, fertilizers, and pesticides vis-à-vis ginning and marketing companies, as well as in dealings with cotton trading companies that set prices based on world markets. These negotiations with national cotton companies and the World Trade Organization are central to the setting of global cotton prices and so shape how and where returns to the crop are distributed among growers, ginners, and traders. Bassett’s research also traces the relationship between currency values and farmers’ incomes. For example, cotton trades globally in U.S. dollars, and yet currencies in Burkina Faso and Mali are pegged to the Euro. The recent devaluation of the dollar relative to the Euro thus reduced cotton farmers’ returns on their internationally traded crops. In addition, Bassett’s work reveals that U.S. cotton subsidies result in overproduction by U.S. producers, who generate 40 percent of global cotton production—thereby suppressing global cotton prices. As a result, farmers in West Africa, who do not have access to similar subsidies, face lower prices on international markets, resulting in lowered incomes (see also Friedberg, 2004, for a commodity chain analysis of French bean crops, and Gwynne, 2002, for a study of fruit exports from Chile).

Geographical research aimed at integrating economic, environmental, and social variables across place and scale can shed additional light on the impacts of market liberalization on inequality within states, at the local scale and across the globe. In particular, much could be gained from comparative case studies employing rigorous experimental frameworks that include common questions and metrics to facilitate aggregation and meta-analysis.

SUMMARY

An understanding of the causes and consequences of inequality requires consideration of geographical patterns and networks—whether economic, political, or environmental. Spatial analyses that take explicit account of place-to-place variations and scalar differences can be of particular value in the effort to elucidate the complex interactions between globalization and inequality.