6

National Policies and Programs

Four presenters offered case examples of national-level policies and programs aimed at addressing the obesity problem. Kevin Concannon (Under Secretary for Food, Nutrition, and Consumer Services, Food and Nutrition Service, USDA) and Dana Carr (Director, Health, Mental Health, Environmental Health, and Physical Education Team, Office of Safe and Drug-Free Schools, US Department of Education) summarized some of their departments’ efforts to fund and showcase programs, raise visibility, and promote healthier eating and physical activity. Tim Smith (CEO, UK Food Standards Agency) reported on how his agency relies on cooperation and partnerships to help consumers make healthier choices. Finally, Susan Jebb (UK, Chair of the cross-government Expert Advisory Group on Obesity) presented on Change4Life, a national campaign in which multiple partners have joined forces to translate the scientific evidence on the causes of obesity into eight achievable behaviors.

US DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE: MEETING NUTRITION NEEDS

USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service encompasses 15 nutrition programs (see Box 6-1) as well as the Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, which is responsible for nutrition guidance to the public. Concannon noted that current economic conditions make USDA’s nutrition programs critical. The programs have a total budget of more than $80 billion, about one-half of the department’s total budget. The largest is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (previously known as the Food Stamp Pro-

|

BOX 6-1 US Nutrition Programs That Can Promote Healthier Eating USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service oversees feeding programs with a collective annual budget of more than $80 billion. They include the following:

SOURCE: USDA Food and Nutrition Service, Programs and Services. http://www.fns.usda.gov/fns/services.htm. |

gram), which currently serves about 35 million people, half of whom are children. Forty percent of SNAP households have one or more members who are working but still have insufficient resources to purchase enough food for their households. SNAP and the Child Nutrition programs at schools provide essential food to millions of children.

As of October 1, 2009, 49 states had implemented a new food package for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC Program) that increases the amounts of whole grains, fruits, and vegetables, and low-fat milk provided by the program, among other nutritional improvements, and promotes breastfeeding. The hope is that these changes will have secondary effects across families and communities, not just for women and children enrolled in the WIC program.

Likewise, nutritional quality is improving in USDA Foods, formerly known as the Commodities Program, which provides food in emergency feeding programs and to schools. As reported earlier by Ms. Paradis (see Chapter 4), improvements are being achieved by lowering the salt and sugar content of the foods provided.

Concannon also welcomed the IOM recommendations for revising school lunch and breakfast nutrition guidelines (see Box 4-1 in Chapter 4), which he said are consistent with the department’s HealthierUS Schools criteria. However, only a small percentage of the country’s more than 100,000 schools participating in the School Lunch Program are also participating in the HealthierUS Schools initiative. Concannon remarked that more needs to be done to expand this important initiative.

Concannon noted that awareness and use of the US Dietary Guidelines (MyPyramid, based on the Food Guide Pyramid) are low. More research is needed to understand why this is the case and what to do about it, perhaps tapping into how the private sector influences consumer behaviors. Partnerships with the Ad Council and soon with the National Football League also will bring more attention to the importance of physical activity and healthy eating.

Concannon said the current economic conditions have created more food-insecure households at the same time that state and local governments are challenged to implement programs with declining tax revenues. USDA is trying to simplify its requirements so states can provide better access to nutrition programs for those who need them.

US DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION: PROMOTING PHYSICAL EDUCATION IN US SCHOOLS

Carr explained that the US education system is highly decentralized, with most decisions being made at the state and local levels. In fact, the Department of Education is prohibited from influencing policy, curricula, or

staffing decisions. Thus, the department’s role in promoting physical education is to encourage and suggest rather than to regulate or require.

Status of Physical Education in US Schools

Carr said that, although school systems offer physical education classes and recesses/activity breaks during the school week, few consider physical education an integral part of education, especially as students progress from elementary through high school. All 50 states except Iowa and Minnesota have state physical education standards, although their quality and depth vary. Most state standards reflect or exceed the standards suggested by the National Association of Sport and Physical Education: 150 minutes per week for elementary school students and 225 minutes per week for middle and high school students. This standard is not often attained in schools, however. While almost all schools require some form of physical education, only 4 percent of elementary, 8 percent of middle, and 2 percent of high schools provide daily physical education or the equivalent for the entire school year for all students (see Box 6-2). Recess is offered in most elemen-

|

BOX 6-2 Physical Education Time in US Schools Almost all schools in the United States require some physical education:

A small number of schools provide physical education or its equivalent at least 3 days a week:

Very few schools provide daily physical education or its equivalent for the entire school year for students in all grades:

SOURCE: Lee et al., 2007, as cited by D. Carr. |

tary schools at least several times a week, and many middle and secondary schools have some sort of activity break during the school day. In addition, schools that participate in USDA’s school meals programs must develop a wellness policy that includes a requirement for physical activity goals. Overall, however, most of the policies, according to an outside evaluation, are relatively weak (Chiquiri et al., 2009).

Carol M. White Physical Education Program

The Carol M. White Physical Education Program (PEP) is a federal competitive grant program first authorized as part of the No Child Left Behind legislation. Currently funded at $78 million annually, the grants go to local educational agencies or community organizations to “initiate, expand or improve physical education and nutrition education programs to help students improve fitness and eating habits as well as meet state standards for physical education.” Taken together, the program’s six elements represent a comprehensive physical education and nutrition education program:

-

fitness education and assessment to help students understand, improve, or maintain their physical well-being;

-

instruction in a variety of motor skills and physical activities designed to enhance the physical, mental, and social or emotional development of every student;

-

development of, and instruction in, cognitive concepts about motor skills and physical fitness that support a lifelong healthy lifestyle;

-

opportunities to develop positive social and cooperative skills through participation in physical activity;

-

instruction in healthy eating habits and good nutrition; and

-

opportunities for professional development for teachers of physical education so they can stay abreast of the latest research, issues, and trends in the field of physical education.

The principal PEP outcome measured is the number of students who engage in 150 (elementary) or 225 (secondary) minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week. Some schools track body mass index (BMI) and obesity rates, although Carr noted that the grants’ time period is too short to see large-scale changes. Looking ahead, the department is considering a restructuring of the program, with a greater emphasis on comprehensive, community-focused, integrated programming that covers all six of the program elements.

Carr also briefly discussed other Department of Education initiatives to support students’ physical activity. Fueled and Fit: Ready to Learn is

a department-wide campaign to highlight the research-based connection between proper physical fitness/nutrition and student achievement. In addition, department officials are visiting schools to highlight the importance of wellness and fitness. Carr said White House leadership is also helpful in promoting child wellness efforts.

UK FOOD STANDARDS AGENCY: ENCOURAGING HEALTHIER EATING

The UK Food Standards Agency is a nonministerial government department responsible for ensuring food safety and dealing with other consumer-focused issues throughout the United Kingdom. Smith reported that about one-third of the agency’s resources are spent on issues related to obesity and healthy eating. Much less regulation is involved in addressing these issues as compared with the agency’s food safety responsibilities.

A Focus on Partnerships

Smith observed that working in partnerships, as the UK Food Standards Agency does, can result in reformulated products, better messaging about nutrition to consumers at the point of purchase, and other changes that can promote better health. The agency’s focus in addressing obesity issues is on evidence-based, largely voluntary initiatives involving businesses, consumer groups, and public health and other organizations. To achieve “safe food and healthy eating for all,” the agency provides consumer advice and conducts campaigns (to influence people), recommends reformulations and more sensible portion sizes (products), and suggests labeling and promotions (the environment). The goal is to provide consumers with the knowledge and skills to prepare and choose healthy meals—a goal Smith acknowledged is complex. One way in which this goal is being pursued is through partnerships with businesses and civil society centered on product reformulations and campaigns. The agency is developing voluntary standards for many products to make them healthier. As an example, companies agreed to lower the salt content in bread, a measure estimated to save 3,500 to 4,000 lives a year. Similar strategies in which companies take voluntary measures are being applied to fat, sugar, and calories.

In the United Kingdom, five companies account for 84 percent of the retail grocery business, which makes them a more concentrated bloc than the big food brand holders. They understand their customers and how to affect behaviors, and the agency also tries to tap into that understanding. The agency’s awareness campaigns have a limited budget, which means it must use its funds wisely. It funds the provision of simple actionable tips

for consumers, efforts to improve labeling on food products, signage and other nutritional information within stores, and local projects.

Food Labeling

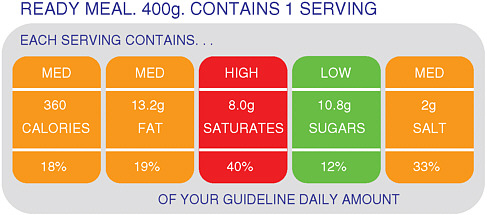

The Food Standards Agency is responsible for front-of-pack nutrition labeling and has actively worked to make the labels more informative for consumers. To that end, it developed several possible label formats that are prominent, easy to read, simple to use, and based on scientific evidence. They are coded with what the agency calls “traffic light colours” in the hope that consumers will minimize their purchases of food with “red” (unhealthier) ingredients and increase their purchases of food with “green” (healthier) ingredients. Moreover, retailers and manufacturers will receive an incentive to reformulate their products to avoid the “red” label. Through consumer testing, the agency learned that the most effective label (see Figure 6-1) has words that describe the nutrition content clearly; the “traffic light” colour scheme; and numbers that show how the food contributes to the EU Guideline Daily Amount of calories, fats, sugars, and salt.

Catering (e.g., take-out food, restaurants, fast food) is also a large market, only slightly smaller overall than the grocery industry. Unlike the grocery industry, the catering market is highly dispersed, encompassing about 250,000 casual dining establishments, many of them small businesses. Twenty-one companies, which Smith termed “trailblazers,” have adopted a calorie labeling system to test consumer response and assess business impact. Those that have signed up have been publicly acknowledged. The

FIGURE 6-1 Most effective food label, as determined through UK consumer research.

labels have the greatest effect at the point of purchase, such as on a menu board or the shelf of a carry-out shop.

Smith concluded with some of the lessons the agency has learned about what works. It has found that disseminating and developing a clear and compelling message that does not get diluted is important. Also, evidence and measurements are necessary to show the impact of the changes that are made. Finally, collaboration and cooperation with the market have advanced the agency’s agenda more quickly than simply relying on legislation, regulation, and mandates.

IMPLEMENTING CHANGE4LIFE

Change4Life is a campaign to change the behaviors that lead to childhood obesity. The disconnect that the campaign addresses is that while obesity has national implications for health and the economy, research shows that people do not relate what they see or hear about obesity to their own situation. Only 5 percent of parents believe their children are overweight or obese, despite data showing that the number is many times greater.

A large body of research—academic, consumer, and ethnographic—was consolidated to develop the campaign. Researchers lived and ate with families, installed cameras in kitchens, went on shopping trips, and looked at shopping receipts. They derived many insights, but according to Jebb, five in particular shaped the philosophy behind Change4Life:

-

Parents acknowledge childhood obesity is a problem, but not for their family.

-

Parents underestimate the amount they and their children eat and overestimate the amount of physical activity.

-

Parents do not see the health risks in sedentary behavior, large portion sizes, snacking, and other behaviors.

-

Parents perceive “healthy living” as a middle-class aspiration that, for many at-risk families, is unattainable or undesirable.

-

Parents prioritize their children’s immediate happiness over long-term health.

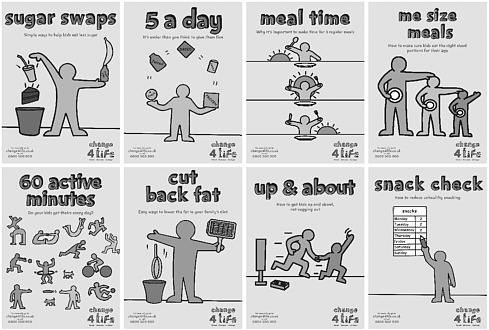

An advertising agency used these insights to develop the messages and branding for the campaign, along with eight consumer-friendly behaviors as an initial focus (see Figure 6-2). The guiding philosophy was that campaigns to change behaviors, such as Change4Life, must be based on science, but their messages must be framed in a way that resonates with consumers. “Change” was used to place an imperative in the brand name; “Life” implies a better life as well as a longer one. The characters in the logo are human but do not represent any particular age, gender, ethnicity, or even

FIGURE 6-2 Change4Life’s eight focus behaviors.

weight status. In fact, the word “obesity” is deliberately omitted. As Jebb observed, the word has strong health connotations and is a clinical diagnosis, but parents and families see it as an insult.

The campaign brings together a broad coalition of partners, in part because families say that health-related messages come to them from the supermarket, the media, schools, their doctor, and other sources. Another impetus behind a broad-based campaign, as called for in the Foresight report, is that systemwide change is needed, not just an advertising campaign. At the same time, Jebb stressed that the campaign is based on an academic and health foundation. Throughout, consumers receive a consistent message with a consistent tone that is empathetic, supportive, and focused on helping rather than lecturing.

Progress to Date

The campaign will take time to have an effect. It includes distinct phases to engage with the delivery chain, reframe the issue to emphasize health over personal appearance, and personalize the issue so parents realize their own children are at risk. Only then will people be ready for the specific knowledge they need to make changes and be receptive to environmental and policy changes.

Change4Life is designed to reach people in all aspects of their daily life. Other programs have adopted its message (e.g., Swim4Life, Dance4Life). People now recite the names of the eight key behaviors, referring to portion control, for example, as “me-size meals.”

A complex, multilevel evaluation framework has been developed. The campaign has already achieved its targets of 370,000 families actively engaged, 750,000 people saying they have taken positive action as a result of the campaign, and 3 million saying the campaign has made them think about their child’s long-term health.

In the next 12 months, a companion brand for pregnant women and parents of children under age 2 will be launched (Start4Life). Materials will also be created for ethnic minority communities in other languages, and the campaign will be extended to adults without children.

DISCUSSION

In the question-and-answer session, Concannon was asked whether the various USDA programs, which are often administered in different departments at the state level, could be brought together to achieve a more coordinated approach. Concannon replied that he and his staff are hosting listening sessions in different areas of the country and could consider this suggestion.

Another questioner asked about considering food and physical activity as part of education. Concannon said the HealthierUS Schools Program does just this, and he hopes this view will extend to more schools. Carr noted that her office is open to suggestions for how to change the Carol M. White Physical Education Program. For example, it is considering a requirement that grantees’ projects encompass all six elements of the program so the projects address both nutrition and physical activity.

Asked to elaborate on private-sector partnerships in Change4Life, Jebb said such partnerships are essential to increase the investment and diffuse the message, but the message must be managed to maintain the credibility and reputation of the brand. Companies sign on to core terms of engagement through a partnership agreement. Guidelines are being developed for the use of Change4Life in retail food settings because consumers say they want the health information while shopping.

One participant observed that, from the presentations over the course of the day, an orderly sequence appeared to have occurred in the United Kingdom: from the Foresight report; to the Healthy Weight, Healthy Lives strategy; to action across sectors. In the United States, he said, there appears to have been a breakdown between a report and the government’s following through with action, perhaps because industry and government have different roles in the United States than in the United Kingdom. Jebb said

the change over a relatively short period occurred in the United Kingdom in part because the Foresight report was issued at a time when there was an opportunity to invest. The evidence had existed for a while, but the report articulated a clear strategy and made the case that investing now would save money later; the cross-government agenda was also crucial. In addition, the report was developed in conjunction with policy makers, which helped in translating it from science to action. McPherson pointed out that the report came from the Office of the Chief Scientist, who reports directly to the Prime Minister rather than a cabinet department.