6

Challenges and Opportunities

Workshop speakers and discussants brought up a number of challenges to creating and implementing a RLHS (see Box 6-1).

IMPLEMENTATION OF EHRS

Rapid healthcare learning is dependent on rapid electronic means of communication, and EHRs are a basic foundational element of an ideal RLHS. Yet it has been challenging to achieve widespread adoption of EHRs, reported Dr. Charles Friedman, deputy national coordinator of the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) for Health Information Technology (HIT). A recent survey by his office in 2008 found that only about one-fifth of physicians’ office practices have a four-component basic EHR system, with adoption skewed to larger practices. The survey also found that only about one out of ten hospitals has a basic EHR system with eight key functions fully deployed across all major clinical units.

To spur efforts to computerize the nation’s health records by 2014, Congress included in its American Recovery and Reinvestment Act two sections that together are called the “HITECH” Act. These sections provided an unprecedented $19 billion to stimulate adoption of health IT systems, to provide “meaningful use” of a nationwide interoperable EHR system (Blumenthal, 2009).

Meaningful use is an evolving concept preliminarily defined as adop-

|

BOX 6-1 Challenges to Implementing a RLHS Identified by Workshop Speakers and Participants

|

tion of certified electronic health records, health information exchange, and quality reporting. Meaningful use will be tied to Medicare and Medicaid payment incentives and a policy process led by ONC. Initially, meaningful use will emphasize capturing and sharing data, but by 2013 a higher definition will emerge that emphasizes more advanced care processes, including sophisticated implementation of clinical decision support, which by 2015 will progress toward realization of improved outcomes through enhanced levels of technology. According to Friedman, meaningful use will likely not include the additional elements needed for a RLHS, including gridware, data stewardship, advanced intelligent methods, and means to aggregate information. Yet because these elements will eventually be superimposed on the infrastructure created by the basic elements of an EHR system it is critical that the foundation of EHRs be harmonious and compatible with the higher-level layers that will be added later.

ONC will use financial incentives to boost adoption of EHRs and will promote such adoption by creating a national system of regional extension centers to support providers in adopting and becoming meaningful users of HIT and by creating programs to enhance the number of health IT work-

ers and certify them. As Dr. Friedman pointed out, there is a widespread belief that there currently are not sufficient numbers of health IT workers to enable adoption and connection of EHR systems.

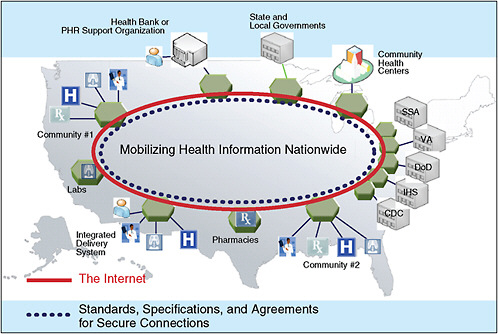

To foster connectivity of EHR systems, ONC will develop standards needed to implement information exchange and quality reporting, as well as programs to ensure privacy and security of EHRs, and will also provide grants to promote health information exchange on a state and territorial level. ONC is also working on the National Health Information Network (NHIN) to mobilize health information by creating a nationwide network of government agencies, community health centers, hospitals, laboratories, pharmacies, and community practices (see Figure 6-1).

To aid this endeavor, the ONC, through the Federal Health Architecture Program, developed an open-source computer tool (CONNECT) that enables connectivity in the NHIN. The NHIN currently consists of 24 entities that have demonstrated the ability to exchange information in real time, and the Network’s capabilities are expected to be expanded in 2010.

“We are making progress on all fronts,” said Dr. Friedman, “but boy do we have a long way to go.” He added later during discussion that meaningful use is currently broadly defined and does not yet call for EHR modules specific to certain practice specialties, such as oncology. Discussant Suanna Bruinooge of ASCO staff pointed out that ASCO, in conjunction with the NCI Center for Biomedical Informatics and Informational Technology and the NCI Community Cancer Centers Program (NCCCP), has an initiative under way to specify the core informatics requirements, data element specifications, and EHR functions needed by practicing oncologists, paving the way for the development of oncology-specific products. “Clinical oncology involves many care processes that may or may not be reflected in the EHR products that are currently on the market,” Ms. Bruinooge pointed out. She said ASCO has also been working with the Certification Commission for Healthcare Information Technology (CCHIT) to develop “a wish list of items that would be helpful to have in an EHR so as to create some interoperability between research systems and EHRs. There is a lot of looking at this in an oncology-specific sense, and hopefully that will be helpful as we are trying to create this system of the future.”

Dr. Wallace pointed out that “an EHR is necessary but insufficient for supporting oncology practice,” and that certain key pieces of information, such as the action plan for a given patient, are not easily captured with EHRs. “The challenge is that there are a whole variety of things that the

EHR does well but there are also things that it does not do particularly well at all,” he said.

DATA QUALITY, COMPLETENESS, AND APPROPRIATE ANALYSES

Lynn Etheredge expressed concern about the data quality in registries and other healthcare databases because “unless you have got it right at the point of entry, it is going to be useless for any other purposes, and unless you define the data, the registries, and the research plan, you will not have learned anything reliable. We have to make building a quality observational system a cornerstone for a learning healthcare system.”

Dr. Edge noted that cancer registry problems are largely related to the quality and the timeliness of the data, and he stressed the need to enhance that quality by linking cancer registry data with administrative data, including payer claims, hospital data, and data from EHRs. Such linkages can both verify and expand the data entered in registries. Dr. Stead pointed out that sets of data from multiple sources might be more statistically reliable than one integrated set of data, because that way there could be interpretation of multiple related signals rather than a single source of information. Unlike with an integrated dataset, “if you aggregate information from multiple sources and use statistical algorithms to interpret them, every new system that you add, every new source you add, actually makes the already existing algorithms more robust,” Dr. Stead said.

Dr. Potosky added that even with linked datasets, there often are data missing from cancer registries, which impedes accurate analyses. For example, in the SEER-Medicare database, cases selected for treatment are often based on nonmeasured characteristics, such as health status, that can only be acquired from patients and are not currently captured in the SEER-Medicare database. Follow-up care and treatments and new comorbidities are also not recorded. Dr. Edge noted that “engaging patients in helping us provide good data may well be a way to get around this [issue of missing data]. The problem is that there are patients who do not provide us that data, and they may be those people who we most need to get the data on.” Dr. Stead suggested that entry of data into a computer be something the clinician and patient do together, with shared records and the aid of patients’ family members. He suggested that patients enter their data at home prior to meeting with their physician, who can review and supplement or change

the data as needed, noting this as an example of the kind of change in roles and processes it will take to make technology work.

Ms. Thames noted that the reported data in cancer registries are not only incomplete, but inconsistent as well. “We do not get consistent, standardized reporting from non-hospital data sources,” she said. In addition, Ms. Thames pointed out that there often are errors in data that are entered manually. She added that cancer surveillance efforts have been limited due to the expense of manually collecting and processing large amounts of data.

Dr. Peter Bach of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center reported a number of problems he had with data quality and completeness when he and his colleagues were engaged in the 2006 Medicare Oncology Demonstration Project, whose goal was to gather more information about patients and treatment patterns in routine cancer care. Providers were asked to include new billing codes for disease status, visit focus, and guideline adherence on claims forms. Physician practices were paid an additional $23 for submitting these codes, and it was done on 66 percent of office visits. Yet critical information was lost because many physician offices created “cheat sheets” to simplify coding and make reporting more efficient. There was a lack of clarity on what it meant to “adhere to guidelines,” with some doctors inaccurately assuming they adhered to guidelines even if they administered another drug in addition to the drugs specified by the guidelines, for instance. “One has to be very careful of the assumptions made when one asks ‘front-line’ physicians to submit data that are analyzable,” Dr. Bach said. He added that one should probably assume that the overarching purpose of data collection will not be easy to convey and will get “lost in translation” as specialty societies, office managers, et cetera, filter what CMS conveys and what physicians see.

Dr. Janet Woodcock of the FDA added that even if EHRs are implemented more widely, “the electronic database is only as good as the data put into it, which are only as good as the people’s understanding of what enterprise they are engaged in.” She suggested more training of community cancer physicians in data collecting and analysis techniques and clinical research. She suggested that the key to acquiring quality data from community practices is by buttressing them with a supportive infrastructure. “You need trained clinical personnel who go to the community and assist the investigators in getting this work done. If you want quality data you have got to help build quality in,” Dr. Woodcock said. She suggested developing structured, convenient, and brief training for community practitioners,

central administrative support to handle clinical trial paperwork, and computerized support of trial documentation. She called for systematized data collection by people who have enough support to do it properly. She suggested creating a broad network of well-supported community-based investigators with central administrative support, noting “you are going to have to support learning” in order to have a learning health system. She said this would require expansion and reconfiguring of the existing clinical research structures in the United States.

Detailing what information needs to be collected, as Kaiser Permanente does, is not sufficient if providers do not provide that information in a standardized way. Dr. Wallace pointed out that many oncologists, including those who have EHRs, do not extensively document the care they provide to their patients, nor do they standardize it, and without such standardization and documentation there is no learning from the care. For example, he noted that although it is standard to give CHOP (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) chemotherapy to patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, there is tremendous variability in the way CHOP is administered (e.g., variability in dosages and interval, and whether cytokines are administered concurrently). “If you have 30 different oncologists, you probably have at least 30 different versions of CHOP,” Dr. Wallace said. “Such variability based on provider [as opposed to patient] nuance is unsafe and compromises our ability to learn,” he added. This variability may be alleviated to some degree by ASCO’s QOPI Program, which recently developed standard chemotherapy treatment plans and summary forms for physicians to document patients’ chemotherapy regimens and responses to treatment, Dr. Jacobsen reported.

Dr. Sox suggested that to counter the problem of missing data, outcomes, and unmeasured confounders in the datasets taken from the records of actual patient care, data-gathering protocols should be established that detail what data physicians need to enter into the record and when, as well as systematic follow-up to ensure there are no missing data. To avoid the problem of confounding by indication, he suggested documenting why one treatment was chosen over another and having more patient-reported outcomes.

Once quality data are collected, they have to be properly integrated, analyzed, and applied. Several speakers pointed out that the observational data collected from clinical practice have numerous potential analytical flaws that must be addressed. For example, Dr. Potosky described a study that assessed the effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy for elderly colon

cancer patients by comparing those that received it to age-, stage-, and comorbidity-matched controls using SEER-Medicare data. In this study, the treatment appeared to be more effective than no adjuvant therapy, but as Dr. Potosky pointed out, probably healthier patients were given the treatment, and thus they were not comparable to the control group used in the study. When randomized controlled clinical trial data have the same findings as those generated in observational studies, Dr. Potosky said, it may validate those finding from observational studies, but sometimes there are no controlled clinical trials that are comparable. In addition, observational studies using cancer registry data may not consider certain variables that foster a selection bias. One such study that assessed the death rates of prostate cancer patients who were treated versus the mortality of those who underwent watchful waiting found those who were treated fared better, Dr. Potosky reported. However this study neglected to assess prostate-cancer-specific deaths, and when those were determined, there were no statistically significant differences between those treated and the control group. There can also be bias due to differential access to care when using claims data.

Some of the statistical shortcomings of observational claims data can be overcome using certain analytical techniques, such as instrumental variable analysis (IVA), Dr. Potosky pointed out. This technique is used in social science and economics studies when randomization is not a feasible practice and can overcome some unknown biases. IVA requires finding a variable that is correlated with the treatment of interest while being (or assumed to be) not causally related to the treatment. The instrumental variable can be used to balance treatment groups. For example, whether the patient resides in an area with high or low use of the tested treatment is a dichotomous instrumental variable posited to be highly correlated with whether or not the patient receives the treatment but not correlated with the outcome of the treatment. Dr. Pototsky concluded by noting that “using SEER-Medicare data to assess the effectiveness of cancer treatment is perilous and potentially misleading. We have to be careful.” He recommended confirming findings of studies using claims data with prospective trials when possible and, if not, then via targeted studies that collect detailed data to assess or account for biases.

Mindful of the dangers of acting on conclusions based on invalid data, Dr. Sox suggested that “we build on analytic guidance systems, so that if I were to sign into a national dataset, I would be at least somewhat informed about good analytic practice. We really need to require basic statistical skills

before people get access to the data, as well as independent clinical epidemiology and statistical review before people act on findings—in other words, do not follow your nose until you know the shortcomings of the data, their implications for statistical validity of the analysis, and the potential for error in applying the conclusions to the patients.” Dr. Sox also suggested that there be some sort of transparent, unbiased peer review prior to researchers’ communicating their results to colleagues. Discussant Amy Guo of Novartis Oncology Health Economics noted that the International Society of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research currently has a task force to develop a guidance on observational studies and how to interpret them. Dr. McGinnis suggested that the National Cancer Policy Forum engage more explicitly on what represent reliable data. However, Dr. Bach cautioned that if too much time is spent planning for observational research, not enough progress will be made. “Some of the activity needs to be pushed forward while the quality of that activity is backed up,” he said.

HARMONIZATION AND STANDARDIZATION

Many speakers talked of the need for harmonization and standardization of both what data are reported and how they are integrated into computer systems. Dr. Neti stressed the need to have appropriate reporting standards so that the data collected can be used not only for evidence-based decision support and health care tailored to individual patients, but also to generate data that can be used for CER. The right type of data needs to be reported to categorize patients and their outcomes and to enable comparisons. “I don’t think we have thought this through completely and we need to put a lot of time and effort into thinking about this,” he said. He added that standard nomenclature that accurately represents the context of data is also critical for the computer analyses needed for CER. Dr. Buetow added that “in biomedicine, context is critical. The same observation of the same word used in a different place means very different things in different biomedical contexts.”

Some data collection standards have been established, but inconsistencies in these standards hamper connectivity and the completeness and usefulness of the data. Ms. Thames called for harmonizing existing cancer registry standards with those generated by the Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE) and Healthcare Information Technology Standards Panel (HITSP) so that cancer surveillance data can be connected to national health IT efforts. Ms. Thames pointed out that there are no standards for

data collection, transmission, and reporting of cancer patients that have been implemented for non-hospital sources. This is problematic given that patients are increasingly acquiring more of their cancer care outside of hospitals at free-standing radiotherapy treatment centers, physician practices, or other settings. A CDC-led working group will test implementation of electronic reporting from provider offices to registries and will try to “move the cancer registry community forward in using consistent standards for electronic provider reporting to improve completeness, timeliness, and quality of cancer registry data,” Ms. Thames said. Efforts are also under way to link cancer registry data to insurance claims data, state all-payers claims data, hospital discharge data, and provider office billing data. Other CDC initiatives have focused on standardization and harmonization of public health records. For example, CDC’s collaboration with IHE has led to international standards for reporting anatomical pathology for public health records.

In discussion, Dr. Abernethy raised the issue of whether there should be data governance at the local, national, and/or global level. Data governance encompasses a convergence of a set of processes relating to data quality, data management, business process management, and risk management. Data governance is necessary to ensure that data connected in networks can be trusted and that there is accountability for poor low data quality. With data governance, there can be positive controls over the processes and methods used by participating data stewards in computerized networks. “The more we think about developing datasets that are highly interoperable, we also have to think about the data governance that goes along with that,”

Dr. Abernethy said. Drs. Stead and Neti agreed that data governance is a major issue that must be tackled in computer networks. Dr. Stead noted that the life span of useful data may be shortened due to changing medical paradigms that may change the current interpretation of data, as well as advances in computer science that may provide new ways of extracting meaningful and useful knowledge from existing data stores. To avoid that problem, he suggested designing information and workflow systems to accommodate disruptive change and archiving data for subsequent reinterpretation in anticipation of future advances in biomedical knowledge or computer applications. “In 1970 there were two types of diabetes. By the mid-90s there were four, and now it is well over twenty depending on what you elect to count. To have actually recorded the raw observation in one of those diabetes terms would have been very lousy compression. It would have been like taking a picture with a one-megapixel camera instead of a sixteen-

megapixel camera,” he said. Consequently, Dr. Stead suggested recording raw data, as well as having IT vendors supply IT systems that permit the separation of data from applications and facilitate data transfers to and from other non-vendor applications in shareable and generally useful formats. “We need to redefine interoperable data as data that can be assembled and interpreted in light of current knowledge and reinterpreted as knowledge advances,” he said.

ENSURING PATIENT PRIVACY AND PORTABILITY OF MEDICAL RECORDS

A major challenge in developing and implementing EHRs, computer grids, and other components of a RLHS is ensuring patient privacy and conformity to HIPAA rules, yet enabling portability of patient records, given that patients are increasingly being cared for at multiple institutions and access to patient data is needed for statistical analyses. With the proper computer hardware and software it is possible to de-identify patients or hide certain data items when patient data are used in the statistical analyses done by researchers. Computer platforms such as caBIG and cancer registries such as SEER have that capability to protect patient privacy, as do the EHR systems used by many institutions. However these automatic controls that shield patient identity or prevent the sharing of patient information can hamper the connectivity of a RLHS, as well as make it difficult for patients to share their medical information with multiple institutions.

Dr. Buetow stressed that “if we really want to share data in HIPAA-compliant forms, we actually have to know what the data are. The bottom line is that there is all this discussion and excitement that we will just segment data and decide what pieces can be shared and what pieces have to be consented or de-identified.” Yet as he pointed out, if it is not precisely known what is contained in each data field, it is not possible to appropriately consent a patient to have the data be shared or de-identified. “We need to define how we can ultimately combine and share the data, because we can then be quite explicit with the people providing us with the data, who will use it and under what circumstances. In the absence of definition, you just cannot do that,” Dr. Buetow said. He suggested that access controls for computer grids require definition of data.

Frydman pointed out that protecting patient privacy was a major concern of ACOR. All of its online communities have closed archives to avoid potential employers’ searching their site for medical information about

job applicants and other such invasions of patient privacy that concern its members. “All of our content has been hidden in a quiet spot of the deep Web never to be found until we find some solution [to these privacy issues],” said Frydman.

Heywood pointed out that privacy limits the amount of meaningful individual data that can be used in statistical analyses. “There will be a contest between what these closed networks can do versus what a fully open network can do, and if we can capture 20 percent of the patients with a disease in a fully open network, the power of the value of that openness will destroy all the other datasets, just in terms of being usable,” Heywood said.

However, Dr. Sommer countered, “I do not think it is realistic to actually think that we are going to get the entire population receptive to sharing their data with everybody openly. We really need to have a dialogue of how do you create that safe, honest broker—that place where genomic and other data can be housed in a safe manner, and you can get the value of what you are doing without it having to be open.”

Dr. Mendelsohn pointed out that transparent data will drive the cost of care down, while driving the quality of care up. “We need to convince Congress of this because HIPAA is inhibiting research. We are not going to get transparent data until we begin to define vocabularies and agree to share data,” he said.

Dr. Sommer underscored the need for portable patient data, pointing out that chordoma patients often have multiple surgeries at multiple institutions and surgeons often cannot acquire the records of prior surgeries. Similarly, oncologists cannot access the prior chemotherapy records of their patients. She called such lack of record sharing a tragedy that impedes quality care. Specifically, she noted the frequent difficulties she had in bringing her son’s imaging files to other institutions that were unable to read them because they used different data formats. She stated that in her experience, up to 30 percent of images from one institution cannot be read by another unless provided in standard DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) format. Consequently, imaging done at one institution had to be duplicated at another. “There must be portability of patient records,” Dr. Woodcock responded, “because there is an issue of radiation exposure when all these films have to be repeated. There should be a convergence on national standards on how it is done.” Dr. Bach agreed that portability of patient records is critical. Heywood added that some patients are even denied their medical records when they request them, and this should not be allowed.

Commenting on lost learning opportunities due to a lack of access to patient data, Dr. Victor Vikram of NCI added that there be consideration of how to use the electronic oncology records of the 500,000 to 600,000 radiation oncology patients each year, who receive some of the most expensive interventions undertaken in cancer patients, that are just sitting in radiation facility files. He suggested this information might be useful.

RAPID REPORTING AND TRANSLATION

Ideally, a RLHS would have rapid reporting of the clinical information it gathers, which will be an advantage for patients, clinicians, and researchers trying to quicken efforts to improve care, but some questioned the value of such rapid reporting unless it is accompanied by efforts to ensure the reliability of the information reported.

There are significant delays in the availability of cancer registry data, pointed out Ms. Thames. “The time gap between the diagnosis of cancer and when the data are made available for analysis can be more than two years,” she said. Dr. Potosky added that the time lag between acquiring the data and being able to analyze them for the linked Medicare-SEER database is about four years. Dr. Edge called for modernizing cancer registries by having more rapid case ascertainment so the data can be used for rapid quality management. Many of the CDC endeavors that Ms. Thames discussed aim to promote more rapid reporting of data by encouraging more standardized, machine-readable electronic health records.

To promote rapid reporting and awareness of research findings, Dr. Sommer suggested that there be open access to medical literature based on studies that are federally funded. This literature should be available to the public because the taxpayers have paid for the studies, she said. She also called for time limits for the review of journal articles that ensure more timely publication so that patients do not have to wait for results.

Discussant Dr. Mia Levy questioned how fast dissemination should be of information that may be of questionable quality. Dr. Sox pointed to the rigorous process that some journals use to review their articles prior to publication. This process includes authors interacting with statisticians and editors. This is an intense, expensive, and sometimes protracted effort that few journals can afford to do right, he said. “The public really looks to journals to evaluate research for them, and that is a public good that journals do,” Dr. Sox said. He then went on to question whether such rigorous review will be carried out in a RLHS where “individuals are working on their comput-

ers at home and then translating [findings] into practice,” without a rigorous statistical review. “I am trying to make you worried about the quality of the evidence that you are getting through that process,” Dr. Sox said.

Dr. Wallace responded that “historical principles are still the right ones about peer review, patient protection, and generalizability. The challenge is that the context could change pretty dramatically. Our orthopedists would argue that the 300 of them meeting monthly is peer review, whether it has been actually published externally or not. Generalizability is redefined when you have access to clinicians and to tools that allow you to dive into a population database and learn. There are a lot of options for how things can be brought forward and a lot of different ways to learn.”

STAKEHOLDER COOPERATION AND PARTICIPATION

Although a RLHS in theory may provide numerous benefits, putting it into practice can be fraught with difficulties, particularly when it comes to the system’s human components. “Whenever you go to buy some technology, you ought to go out to lunch with an anthropologist because the major failures and our major write-offs are when we get enthralled by the electrons and lose track of how people do their work,” said Dr. Wallace. Dr. Buetow concurred, noting that “culture eats strategy for lunch.” Changing culture so that it will be more adapted to a computerized RLHS is a major challenge that cannot be ignored. Buetow pointed out that the culture of academic biomedical research has traditionally been focused on a competitive system of individual investigators and institutions. There can also be competition and a lack of collaboration between stakeholder groups such as patients, physicians, academic researchers, government agencies, payers, and industry. “You are going to have to encourage people to pound their swords into plowshares a lot of the time, and that is not necessarily a trivial undertaking,” he said. “It can be facilitated with technology, but let’s not assume that it just evaporates in the presence of good will.”

Based on what he learned creating caBIG, Dr. Buetow warned that ignoring cultural barriers can cripple such large-scale efforts and that there must be commitment from all levels of participating organizations. “You need engagement all the way from those guys that install printers up to the boardroom if you actually want to be able to do this kind of work,” Dr. Buetow said. Also needed is a willingness of stakeholders to collaborate and join together as a motivated community that drives and directs the

changes needed to make large-scale improvements in the healthcare system, he added.

Dr. Buetow pointed out that much of what prevents data sharing is not technical, but reflects the segmentation of stakeholders into silos by discipline, geography, and sector or reflects concerns about being recognized and/or rewarded for intellectual capital. Establishing new kinds of collaborative activity between and among those silos is critical, using IT as the electronic “glue” to enable each constituency to achieve its organizational goals. He noted later during discussion that cultural factors, including data access issues, have been the main impediments to making computerized healthcare databases compatible across government agencies, such as the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Department of Defense, the CDC, and the NIH. “There aren’t natural tendencies for these groups to play together—you do not get funding for using somebody else’s system,” he said. However, Dr. Buetow struck a note of optimism by pointing out that as various government organizations and other healthcare stakeholders increasingly recognize the benefits of cooperating to achieve the common goal of a RLHS or its subcomponents, they are working more effectively together. The CDC and NCI, in specific, are starting to leverage common architectural frameworks to facilitate interconnectivity, Dr. Buetow said.

The needs of point-of-care physicians also must be addressed for a RLHS to be effective. Dr. Clancy stressed that in order to implement a vision of a RLHS, we have to be able to answer the most pressing question of providers, which is, What’s in this for me? “This question has got to be paramount in our minds at all times. If people are not getting something back for it, if clinicians do not see that this is worth their while, we are going to fail,” she said and added, “Better to collect two data elements that people find incredibly valuable, than to lay out this amazingly complex vision for what could be but does not have anything to do with real life and the needs of patients and their providers.” Although health information technology is a big part of a RLHS, “the electrons are the easiest part of this,” Dr. Clancy said.

Dr. Ganz suggested one incentive for providers participating in a RLHS is the ability to streamline and standardize. The capacity to provide highquality information for clinicians will ultimately make physician practices more efficient, and the use of decision support tools and their ilk can simplify the discussions doctors have with their patients. Dr. Abernethy added that “there is great hunger in the community oncology sector about how to make this work. They see it as improving practice efficiency and patient

satisfaction—as really helping them figure out how to do the best thing,” Dr. Clancy agreed that “what motivates most people who are providing care is actually making it better. The only reason physicians, for the most part, will participate with energy and enthusiasm is if it actually makes their jobs easier by making the right thing to do the easy thing to do. That is something people get real excited about.”

Dr. Bach noted a major barrier to instituting a RLHS is the fact that the focus of most practicing physicians is to treat their current patients adequately. There is little interest, let alone room in their busy schedules, to gather information that might be useful for future patients, he claimed. “It will be hard to get buy-in that downstream learning is valuable. Today’s care is about today’s patient and today’s bill,” Dr. Bach said, adding that physicians who do a lot of clinical trial work may be more amenable to gathering more patient data.

Heywood suggested making physician reimbursements dependent on keeping detailed records on the care provided to patients. He pointed out that shorthand notations of care, such as CHOP, can have variable interpretations and that variability impedes analyses in computerized databases of the outcomes of treatments and whether some treatments are more effective than others. “We should make a rule that says that if you cannot provide patients a computable accurate history of what was done to them, they then have the right to challenge payment for such services,” Heywood said.

Others at the conference pointed out that the inadequate training community physicians often have in regards to clinical research limits their adequate participation. “Physicians think about an ‘n of 1’ experience in terms of decision making, and they have been brainwashed a little bit to look at randomized clinical trials as the gold standard that leads to drug approvals. They have no conception of population-based findings and observational data and their limitations and opportunities,” said Dr. Ganz. She suggested more physician postgraduate learning in this regard, perhaps within the institutions in which they are training. “We have to school a generation of physicians, nurses, and other healthcare providers who are actively engaged in understanding how they can make use of all of this,” Dr. Ganz said.

Dr. Woodcock countered that it is difficult to get already overtaxed medical schools to fit anything more into their curriculums. Mr. Etheredge called for more physician training in the use of decision support tools and models and a better understanding of how they work. Dr. Woodcock disagreed. “I’m a real advocate of modeling, but the average physician tells us,

‘just give us the answer,’” she said. She noted that the FDA always tries to simplify what information it provides in drug or diagnostic labels, because “doctors’ lives are so busy.” Dr. McGinnis opined that the upcoming generation of physicians will be able to access algorithms online in the process of care, but probably will not be interested in understanding how models are built, so more effort should be put in vetting the models and getting universal acceptance of them rather than teaching conceptual understanding.

CHOOSING APPROPRIATE IT

Technology can both help and hinder clinical improvements, Dr. Stead noted in his presentation, and pointed out that IT isn’t used as effectively as it could be to aid clinicians. Dr. Stead chaired the National Research Council (NRC) report Computational Technology for Effective Health Care, which revealed significant shortcomings in how health IT was put into practice (NRC, 2009). For example, the committee noted that patients’ medical records, even when computerized, were so fragmented in some institutions that there often were five different members of a care team, each examining the same patient’s records on their individual computers, who were unable to integrate such information electronically.

In addition, Dr. Stead pointed out that although care providers spend a great deal of time electronically documenting what they did for patients, much of this documentation occurred after the fact for regulatory, legal, or billing and business purposes, often merely mimicking paper-based forms. In some cases, IT applications actually increased the time providers spent on administrative tasks as opposed to providing direct patient care. With few exceptions, because the data collected were not used to provide clinicians with evidence-based decision support and feedback, or to link clinical care and research, clinicians generally did not see these electronic data as being useful to improve their clinical care.

About 90 percent of how healthcare IT is used today focuses on applying techniques for automated repetitive actions, which are only applicable on small-scale systems, according to Dr. Stead. Little attention is given to the more important tasks of boosting connectivity of people and systems, data mining, and decision support, and “where we do these other things, we bolt them onto an automation core so our ability to do data processing automation kind of work becomes the rate-limiting step. It will not work and we have to rebalance our portfolio to use the other techniques,”

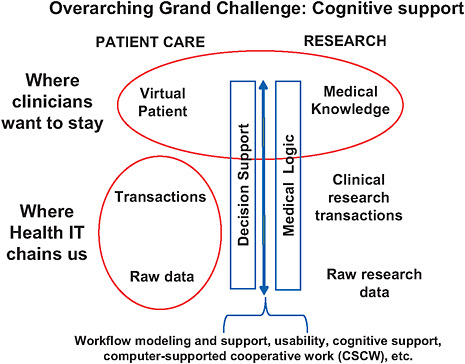

Dr. Stead said. A possible framework for future healthcare IT is depicted in Figure 6-2.

Dr. Stead suggested that rather than having data entered by clinicians into computer systems, intelligent sensors could create an automatic self-documenting environment of the medically significant content of the interactions of providers with their patients. IT systems could then use this content, along with other relevant clinical information, to model a virtual patient and suggest and support holistic care plans used by multiple decision makers.

FIGURE 6-2 The virtual patient—component view of systems-supported, evidence-based practice.

NOTE: Mapping from medical logic to cognitive decision support is the process of applying general knowledge to a care process and then to a specific patient and his or her medical condition(s). This mapping involves workflow modeling and support, usability, cognitive support, and computer-supported cooperative work and is influenced by many nonmedical factors, such as resource constraints (cost-effectiveness analysis, value of information), patient values and preferences, cost, time, and so on.

SOURCE: NRC, 2009.

TABLE 6-1 Paradigm Shift Necessary for More Successful Computational Technology for Effective Health Care

|

Old |

New |

|

One integrated set of data |

Sets of data from multiple sources |

|

Capture data in standardized terminology |

Capture raw signal and annotate with standard terminology |

|

Single source of truth |

Current interpretation of multiple, related signals |

|

Seamless transfer among systems |

Visualization of the collective output of relevant systems |

|

Clinician uses the computer to update the record during the patient visit |

Clinician and patient work together with shared records and information |

|

System provides transaction-level data |

System provides cognitive support |

|

Work processes are programmed and adapted through nonsystematic work-around |

People, process, and technology work together as a system |

|

SOURCE: Stead, 2009. |

|

Summarizing his approach to helping people think about electronic health records based on his experience, Dr. Stead contrasted old and new ways of thinking, highlighting the paradigm shift needed (see Table 6-1).