8

Simultaneous Sessions

The second session was organized into four breakout sessions, each with presentations and discussions describing the development of Chinese and Indian innovation capacity in a broad sector of the economy or set of related industries – information technology and communications, transport equipment (automobiles and aircraft), pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, and energy. The sessions were intended to highlight and compare key microeconomic trends rather than thoroughly analyze each sector.

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND COMMUNICATIONS

At the outset of the IT session, Ashish Arora of Carnegie Mellon University made two main points about the global software sector. First, the United States still dominates the software industry in a unique way; second, South Korea, Israel, and Japan represent a group of comparably sized second tier producers. In his view, the main story is the “utter dominance” by the United States, with Israel leading the group of “underdog” countries. The United States continues to hold this dominance because it is home to a key population of highly sophisticated software users (Table 3).

In China, 90 percent of total software sales are to the domestic market, a market pulled along by the country’s economic boom rather than leading it. Nevertheless, the technological competence among Chinese firms probably exceeds that of Indian firms. Indian firms are moving into higher value-added software development, Arora said, but not necessarily advancing technology. “Human capital is the key,” he emphasized (Table 4).

Roy Singham of ThoughtWorks, Inc., had a different perspective on the shifting locus of IT innovation. “We’re at the beginning of a 150-year shift in power to Asia.” The shift will not be drastic, he speculated. The European Union will remain a significant part of the picture for some time, as will Brazil and Argentina. Still, he suggested, a new “tricycle of innovation” will hinge on the centers of Stockholm, Beijing, and Bangalore.

The emphasis on human capital and value for social capital, Singham said, explains Scandinavia’s lead in global IT competitiveness per capita. A value on collaboration, not just competitiveness, can spur global innovation. In this new environment, agility of innovation and fast solutions for new business models will command a premium. He posited that there are two revolutions taking place--one on the process side of enterprise and a second on the product side. In terms of process, he expects to see a less hierarchical approach than he observed on a recent tour of Indian software companies, which reflected the assembly line model from the industrial revolution. Arora responded that the factory model remains workable in how it addresses the high turnover of employees and ensures a company can consistently deliver its product. Is the factory approach a cause of staff turnover or an effect of it? Singham replied that ThoughtWorks has a low 5 percent attrition rate among its staff in India, in large part because it values its employees.

A generation ago the Asian diaspora tended to settle in the United States and elsewhere overseas, but now they are likely to return to their home countries. That change will have a profound effect, according to Singham, who questioned, “How did the United States, which was home of open intellectual debate, lose that advantage?”

TABLE 3 The International SW Industry (2002)

|

Countries |

Sales ($B) |

Empl (‘000) |

Sales/Empl |

Sales/GDP |

|

Brazil * |

7.7 |

160 ** |

45.5 ** |

1.50% |

|

China |

13.3 |

190 ** |

37.6 |

1.1 |

|

India |

12.5 |

250 |

50 |

2.5 |

|

Ireland (MNE) |

12.3 |

15.3 |

803.9 |

11 |

|

Ireland (Dom) |

1.6 |

12.6 |

127 |

1.3 |

|

Israel * |

4.1 |

15 |

273.3 |

3.7 |

|

US |

200 |

1024 |

195.3 |

2 |

|

Japan ** |

85 |

534 |

159.2 |

2 |

|

Germany * |

39.8 |

300 |

132.7 |

2.2 |

|

Argentina ** |

1.35 |

15 |

89.3 |

0.5 |

|

SOURCE: Adapted from Arora, A. & Alfonso Gambardella, 2005. "The Globalization of the Software Industry: Perspectives and Opportunities for Developed and Developing Countries," in: Innovation Policy and the Economy, Volume 5, pages 1-32 National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. *=2001; **=2000 |

||||

TABLE 4 The Software (SW) Industry in India ($B USD)

|

|

FY 2004 |

FY 2005 |

FY 2006 |

FY 2007 |

|

IT Services |

10.4 |

13.5 |

17.8 |

23.5 |

|

-Exports |

7.3 |

10.0 |

13.3 |

18.0 |

|

-Domestic |

3.1 |

3.5 |

4.5 |

5.5 |

|

ITES-BPO |

3.4 |

5.2 |

7.2 |

9.5 |

|

-Exports |

3.1 |

4.6 |

6.3 |

8.4 |

|

-Domestic |

0.3 |

0.6 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

|

Eng, R&D Serv and Products |

2.9 |

3.9 |

5.3 |

6.5 |

|

-Exports |

2.5 |

3.1 |

4.0 |

4.9 |

|

-Domestic |

0.4 |

0.8 |

1.3 |

1.6 |

|

Total Software and Services Revenues |

16.7 |

22.6 |

30.3 |

39.5 |

|

SW Exports |

12.9 |

17.7 |

23.6 |

31.3 |

|

Hardware |

5.0 |

5.9 |

7.0 |

8.5 |

|

Total IT Industry (including Hardware) |

21.6 |

28.4 |

37.4 |

48.0 |

|

SOURCE: Adapted from Indian IT-BPO Industry Factsheet (2008) NASSCOM |

||||

Frictions in labor markets are different from the frictions that exist within capital markets. Singham posited that talent is less transportable than capital—a point that was debated. Arora maintained that capital and talent can both move; the sticky part, in his opinion, is proximity to users.

Jason Dedrick of the University of California, Irvine, spoke on IT market opportunities in China and India (Table 5). He amplified a theme noted by others—innovation is most intense in sectors where users are nearby. This means that the greatest potential for innovation exists in sectors where Chinese and Indian markets are growing rapidly. By 2006 there were 415 million cell phone users in China, compared to 15 million in India. Personal computer shipments that year to China were 28 million; to India, 7.7 million. In understanding these markets we will see where different products are likely to emerge. Multinational corporations are struggling with this shift, while it creates opportunities for local firms in both countries.

By building on their domestic market base, local firms can launch into the global market, as Haier and Huawei in China have done. The Chinese government’s strategy of developing domestic technology and dictating standards may be a miscalculation, insofar as it is hard for any firm to keep teams moving ahead on both the domestic standard and the international format.

Table 5 Emerging Market Opportunities

|

|

China |

India |

|

Installed PC base, 2005 |

54 million |

15 M |

|

PC shipments, 2006 |

28 M |

7.5 M |

|

Domestic software market |

$3.9 B |

$1.4 B |

|

Domestic IT services market |

$6.2 B |

$3.7 B |

|

Cell phones in use, 2006 |

415 M |

150 M |

|

Cell phone shipments, 2006 |

130 M |

75 M* |

|

SOURCE: Dedrick, *new subscribers |

||

Indian firms are gaining in scale and scope, with implications for U.S. enterprise. One implication for U.S. workers is that there will be greater needs for project management, cross-technology skills, business and industry knowledge, as well as cross-cultural management. Dedrick characterized this as a need for “T-shaped people,” with the vertical base of the T representing technical depth and the top horizontal bar representing broad management familiarity.

Balaji Yallavalli of Infosys Technologies, Ltd., illustrated how the “world is flattening” by describing his own situation—managing a company based in India, working from Plano, Texas, and New York. The structural shift in demographics is strengthening the position of developing countries. At the same time, technological applications are “being pushed out of companies” and into the hands of their customers, in various ways ranging from air passengers who print their own boarding passes, to greater user involvement in software development. His observations about shifts in the dominant modes of thinking resonated with other participants in the IT session. Technology can help predict the future turns in a sector and identify ways to weather those changes. Yallavalli described Infosys as “a company that can scale ideas quickly,” not an R&D-based company, but one based on innovation to meet business model needs. He cited a recent news article suggesting that outsourcing was sufficiently successful that India was now exporting jobs abroad.

Yallavalli reiterated that with time-to-market shrinking for innovations and with customers wanting to be part of value creation, it is not as necessary to climb the technological ladder as it is to move toward customer satisfaction and the value chain. “Innovation is the only means to sustain customer loyalty in a flattening world,” he said.

Lee Ting of of Lenovo observed, “True innovation occurs [mainly] at headquarters.” In Lenovo’s case, they aimed to keep innovation hubs intact in a larger system. For example, the ThinkPad design process is still driven from its former IBM base in Raleigh, North Carolina, although Lenovo is based in Taiwan. Domestic firms in China are well situated to innovate for the domestic market and get ahead of MNCs. PayPal, for example, shut down its Chinese operation because it did not adapt to the Chinese payment preferences. There is not only a need for innovation based on technology but also for innovative new business models.

Patrick Canavan of Motorola, the session moderator, told how in Motorola’s experience the company’s innovation in China came, in one instance, from a disappointed company executive who engaged local technical expertise to find a market sensitive solution. Cycles of staff departures among competitors affect the dynamics of innovation.

On the question of whether formal education would play a large role in the shift ahead, Singham noted that 10 percent of ThoughtWorks employees do not have bachelor’s degrees, just as some leaders of the U.S. software industry lack them. “Software is a weird world,” he said, where innovation is correlated more with creativity than with education. Creativity is more crucial in designing new software than in engineering a new hardware chip, for example, and is the quality on which ThoughtWorks places a premium. Singham insisted that the company has a global cap on the number of engineers it hires. “We believe they stifle creativity,” he said provocatively.

Alongside growing creativity, there is a growing acceptance of risk in China and India, linked to their demographic changes. There are also structural differences in risk-taking in different societies. Bankruptcy in Japan, for example, can spell disaster; in Silicon Valley it

is far easier to recover from bankruptcy. The latter encourages innovators.

Asked about what activities may shift to Asia, the panel made several suggestions. State-owned enterprises and their international partnerships will shift the dynamic, Canavan noted. For example, China Mobile’s stake in the Pakistan market and China’s investment in Africa would help China grow its influence in the global market. Others felt the shift would depend less on government policies and more on technological innovation coming out of Indian firms and business-model innovations in China. By 2020, one predicted, India’s largest firms will be capitalizing on the domestic market there.

Martin Kenney pursued the question of different types of creativity, in particular at Infosys. Yallavalli acknowledged tensions between fostering an open and creative environment on the company campus and the expectations of stakeholders to find a serious, no-nonsense approach. Among their clients, he noted a kind of double standard; they want employees to be creative but not at the expense of the existing corporate structure.

TRANSPORT EQUIPMENT

This session focused primarily on cars, trucks, and civilian and military aircraft as these are expected to be areas of major domestic market growth and manufacturing capacity expansion in both China and India.

In the part of the session devoted to aviation, Thomas Pickering from Boeing discussed that company’s operations and plans in both India and China. In particular he noted that the opening of Indian defense procurement will mean greater opportunities in that country for western companies such as Boeing and Martin Marietta. It promised to become a major market.

Rishikesha Krishnan of the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore reported that the Indian government is thinking about what it will take to move from its current engineering design capabilities in aviation and aerospace to the development of a domestic production capacity in those areas. Such a production capacity is largely nonexistent in India at the moment, but the government aspires to develop one.

Warren Harris, the chief executive officer of the design services firm INCAT, offered the complementary observation that the automotive and aerospace industries are moving from outsourcing to globalizing innovation. That is, where innovation in these industries has been limited mostly to companies in the developed countries, it is now being spread much more broadly around the globe. Access to qualified personnel is a key driver in this globalization of innovation, he said.

A principal theme of the session was the growing sophistication of engineering services in India and China. “If anyone has the notion that the variety and types of engineering services being outsourced to India are at the lower end of the value-added chain, they are seriously out of date,” according to Pete Engardio, BusinessWeek senior writer, who described some of the design work he observed on recent visits to a number of service firms in India. Companies there are working on a variety of sophisticated projects in the aviation and automotive sectors, he said, from fuselage design and avionics to passenger car platforms, and this work is being done in India not only by the multinationals but also by Indian-owned and domestically headquartered companies.

This development, in Engardio’s view, is a function of the disintegration of vertical integration in global manufacturing, the emphasis on modular production and much shorter production cycles, the importance of embedded software in many products, and the effects of various government policies, such as those that require a significant domestic contribution in manufactured items. The movement of design services to places like India and China has in large part been a function of cost, he said, but increasingly it is also being done in pursuit of talent. In short-run economic terms, the most important topic discussed in the session was the rapid growth of both the Chinese and Indian markets for passenger vehicles and the efforts of domestic producers in both countries to ensure that they have the capacity to meet that demand.

Paul McCarthy, PriceWaterhouseCoopers consultant on the automotive industries in both

India and China, gave an overview of market trends in both countries. Between 2006 and 2011, China’s production is projected to increase by nearly 50 percent, while India’s production is expected to jump by nearly 110 percent in the same period. Although Chinese production capacity is still more than three times as large as India’s—7 million versus just over 2 million vehicles per year – expansion is occurring at comparable rates.

McCarthy characterized innovation in the two industries in different dimensions. One pattern is domestic companies’ adoption of Western and Japanese innovations by copying, licensing, or entering into joint ventures. He illustrated Chinese and Indian innovation, in its most primitive form, with a series photographs of pairs of vehicles—for example, a 2007 pickup truck made by the Chinese company Chamco and a 2004 Toyota Tundra. They appeared nearly identical.

Purchasing rights to designs and components, on the other hand, offers an opportunity for learning by domestic companies as well as business opportunities for foreign intellectual property holders. There are a number of examples, including Cummins’ licensing of its diesel engine technology to Dongfeng of China and Tata of India.

Multinationals’ R&D activity in China or India constitutes a second type of innovation common to other industries. “Every major multinational automaker has at least one research facility in either India or China,” McCarthy observed, the result as in other cases of lower costs and skilled labor availability.

The third category consists of local companies developing innovations independent of MNCs. One example is Tata’s recently announced development of an extremely low-cost automobile for mass markets with wide income disparities. This may drive a low-cost automobile revolution among international as well as Chinese and Indian manufacturers.

Other session participants focused primarily on the development of the Chinese passenger automobile market, which Zheng Jane Zhao of the University of Kansas Business School projected will continue to grow at the current robust rate for about 15 more years, becoming a huge factor in the global market. Every major multinational car manufacturer has a presence in China, Zhao said, but these companies mainly conduct only component innovation in China and keep their architectural innovation at home. It is the architectural innovation—changing the overall layout of the vehicle, including power train development—that is the core competency of automakers, and the multinationals generally try to protect their core competencies by doing this architectural innovation at home.

In the past, multinationals have accounted for almost all the cars sold in China, McCarthy noted, but that is rapidly changing. In 2007, cars made by domestic manufacturers accounted for an estimated 32 percent of the domestic car market, up from just 11 percent in 2004. The Chinese auto makers are competing on the low end, and, as a result, are far less profitable than the multinational auto makers selling cars in China. Furthermore, the R&D expenditures of Chinese automotive companies are still very low compared to producers in developed countries—0.63 percent versus 3 to 5 percent in western companies. “Even though we are seeing more and more market and design innovation, technical innovation still remains weak,” McCarthy said. “Chinese companies need to develop their R&D capability in core technologies, such as engine, transmission, and chassis.”

The Chinese government is encouraging the automotive industry to develop its own indigenous innovation, and China’s 11th Five-Year Plan explicitly singles out automotive innovation and development for advancement. The government’s objectives outlined in the plan include upgrading local R&D capabilities, creating more environmentally friendly and energy-efficient vehicles, building indigenous brands, and speeding up industry consolidation. As for prospects that Chinese manufacturers will become major suppliers in other markets, the development of brand identification is perhaps even more critical than technological innovation. Chinese auto makers are handicapped in this regard not only by a history of poor quality but also by characteristics of the domestic market. In particular, brand name recognition has little economic value in China.

Furthermore, Zhao said, the Chinese automotive industry is hampered by its

fragmentation, with many smaller companies competing for market share. “Most car makers are not producing at economic scale,” she said, “and 121 out of 128 car brands produce less than 0.1 million units each year. There are too many players in each segment, and yet new entrants are still entering.” Thus the government is pushing for consolidation, and the MNCs may be helping the process. Volkswagen, for example, has consolidated production planning and purchasing processes between its two Chinese joint venture partners. It is likely that consolidation will be pronounced trend in the industry in the next few years, Zhao suggested.

Over the past decade, Morgenthaler noted, Chinese auto makers have generally relied on alliances with multinationals for much of their innovation, but this is being questioned because the alliances limit the Chinese companies’ ability to control their own destiny and brand identity. Thus they are now tending to learn by outsourcing and acquisitions rather than by alliances.

Meanwhile, according to McCarthy, Chinese firms are aspiring to move up the ladder from copier to joint venture partner, to semi- and then fully independent innovator. The best known automaker, Chery, he judged to be somewhere between phase two and phase three, with government-supported ambitions to achieve phase four in the next few years.

PHARMACEUTICALS AND BIOTECHNOLOGY

Charles Cooney of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who chaired the breakout session on pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, used the concept of value chain to frame a discussion of the role of China and India in the biopharma sector. A therapeutic product goes through a series of steps in its development—discovery, formulation, clinical trials, regulatory approval, manufacturing, and distribution. Each of those steps may offer opportunities for an emerging economy to participate. Which steps in this value chain are the most likely areas that China and India will make major contributions in the next decade or two?

Recently, Cooney said, a number of multinational pharmaceutical and biotech corporations have been outsourcing work to China and India. This work represents several different points in the value chain. A number of multinationals have R&D efforts in the two countries, for example, and many of them are developing partnerships with indigenous companies, particularly in India, to work on early-stage discovery and other research. There are also a large number of multinationals doing manufacturing in the two countries. India has the largest number of FDA-approved manufacturing facilities outside the United States, while China is somewhat less advanced with respect to best manufacturing practices.

Both countries also serve as the site for much clinical trial work, Cooney said; and quite recently China has surpassed India as the site of the largest number of trials outside of the developed countries. Vincent Ling, vice president of molecular biology at Dragonfly Sciences, documented the shift in locus of clinical trials with Food and Drug Administration data. In 1997, 85 percent of all safety and efficacy clinical drug trials were performed in the United States, 10 percent in Europe, and only 5 percent in the rest of the world. By 2005, the United States accounted for only 66 percent of clinical trials, Europe 13 percent, and the ROW more than 20 percent.

Several factors are driving this offshoring, Cooney said, including the lower cost of building manufacturing facilities in India and China compared with the United States, as well as lower labor costs, although the latter are increasing rapidly. Multinational corporations are also attracted by the large markets in the two countries and, on the clinical side, by the extremely large patient populations.

Intellectual property regimes are another determinant of how the biopharma sector has evolved in China and India, according to Cooney. For example, Indian patent law for many years allowed only pharmaceutical process, not product, patents. As a result, Indian companies have highly developed process technologies and strength in manufacturing and selling generic drugs. In Cooney’s opinion, Indian and Chinese companies will soon dominate the generic sector.

Ling described the corporate experience of Dragonfly Sciences in performing a range of specialized and customized activities. Dragonfly performs discovery biology, serves as an overflow laboratory for large pharmaceutical companies, and acts as an implementation lab for virtual biotech companies that need research performed. Because of the high cost of these services in the United States, Dragonfly set up its main operations in China, with a small headquarters staff in the United States. Currently, the Shanghai laboratory employs 20 full-time workers while the U.S. headquarters office has three.

The imperative for the pharmaceutical industry, according to Ling, is to manage the escalating cost of drug development, testing and approval and/or increase the success rate in the testing phase. “You have outsourcing simply because the cost has to be managed,” he said. “As more small and mid-tier pharmaceutical companies strive to become clinical organizations, the high cost and low success rates of human studies will create significant challenges for that sector and lead them to adopt outsourcing and other clinical practices that big pharma is using to control costs and manage risks.”

Speaking of Dragonfly’s specific experience in outsourcing to China, Ling summarized a number of advantages and disadvantages. A major advantage is the cost of scientific labor in Shanghai, which is one-fourth to one-seventh the cost in the United States. On the other hand, the Chinese biotechnology industry is very young and most scientists are newly minted Ph.D.s or have less than three years of experience. Chinese bioscientists tend to have good learning skills but most of them perform well below the level of their peers in the United States and Western Europe. U.S.-trained biomedical scientists generally want to remain in the United States to conduct research. Regulation of biomedical research and product development is less onerous in China than in the United States, according to Ling; but it also tends to be more arbitrary and unpredictable. Dragonfly’s Shanghai laboratory was set up to comply with U.S. as well as Chinese regulations. Nevertheless, Chinese inspectors often provided little guidance about what was expected. Chinese workers are willing to work hard and comply with instructions, yet they are reluctant to participate in problem-solving discussions or to offer new ideas and opinions.

One of the keys to Dragonfly’s outsourcing has been maintaining what Ling called “granularity,” where data are regularly communicated from Shanghai to the U.S. office. Because the biological experiments they perform are generally messy and often produce unanticipated results, the experiments need to be overseen by an experienced manager with a constant eye on the data being produced. Furthermore, Dragonfly’s MNC clients often lack confidence in the integrity of the research results. They required that the Shanghai workers upload data daily for review by the U.S. staff.

Another disadvantage of working in China is the cost of reagents and the difficulty in getting them quickly. “They may have all the equipment,” Ling opined, “but you cannot necessarily get the materials.” In spite of these disadvantages and inconveniences, Ling concluded, the lower cost of labor outweighs all other factors. Ling expects this advantage to persist at least for the next decade.

Surprisingly, another part of the value chain that may offer opportunities for innovators in China and India is the discovery of new pharmaceuticals. Kuan Wang from the National Institutes of Health spoke about the possibility of using knowledge from the traditional medicines of China and India to develop new treatments. There have been many success stories involving the traditional herb medicines as sources of drug discovery, Wang said. GL-331 is an anticancer drug in Phase II trials, for example, and PA-334 is in preclinical studies for use as an inhibitor of HIV reverse transcriptase. A more familiar example is curcumin, the active substance in the spice turmeric. Cell and animal studies have indicated that it has anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory, and anti-pain properties and that it may be useful against neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s. In its natural form its effectiveness is limited because of poor solubility in water and poor bioavailability, but encapsulating it in nanoparticles has been shown

to increase its bioavailability, and data suggest that curcumin in this form inhibits pancreatic cancer cell lines.

China has a number of ongoing efforts to push the development of traditional medicine, Wang said, but there are a number of challenges facing that development. Foremost is the lack of western-style placebo-controlled studies establishing the efficacy of these traditional treatments. A great deal of research must be done to explore the clinical pharmacology and pharmacodynamics of these traditional medicines; and studies are needed on how these medicines behave when combined with western medicine, including the possibility of adverse interactions. Intellectual property rights will also be tricky to establish and disputes difficult to resolve. Traditional medicines themselves cannot be patented, but derivatives can be, so research will be needed both to identify the effective ingredients in traditional medicines and to work from those ingredients to discover compounds that can be patented. Finally, there is no large international market for traditional medicine from India and China. Nonetheless, if these challenges can be overcome, traditional medicine can provide a platform from which China and India could become innovators in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology worlds.

ENERGY

The energy session’s first speaker, Dilip Ahuja of the National Institute for Advanced Studies in Bangalore, India, described China’s and India’s role in the link between energy and climate change. Because more than two-thirds of anthropogenic greenhouse gases are energy-related, Ahuja said, the need to reduce carbon emissions from power generation is clear. And because the greatest growth in power demand over the next several decades is projected to come from China and India, innovations in the production, distribution, and use of energy in these two countries will play a major role in determining how well the world responds to the threat of global warming.

On the other hand, many in China and India are skeptical about the motivations of those in the developed countries who tell those in the developing countries that they need to worry more about climate change. There is a suspicion that the arguments for reducing greenhouse gases are really an attempt to slow down growth in China and India as they become serious economic competitors of the United States, Europe, and Japan. A new approach is needed if China and India are to work with the developed countries on climate change.

The first step out of the impasse, according to Ahuja, will be for the developed countries to transform their emissions goals into firm commitments, as articulated by the Global Leadership for Climate Action, which recommended that developed countries should commit to reducing their emissions by 30 percent between 2013 and 2020, while the rapidly industrializing countries, such as India and China, should reduce their energy intensity by a similar amount. Energy intensity is the ratio of a country’s energy consumption to its gross domestic product (GDP), so it measures how much energy a country uses to produce a certain economic output.

Reducing energy intensity by this amount in China and India will require a variety of innovations but is feasible, Ahuja said. Over the past several decades, for instance, the average energy intensity of all countries around the world has been declining by 1.25 percent per year. In India, energy intensity has declined by about half over the past 30 years.

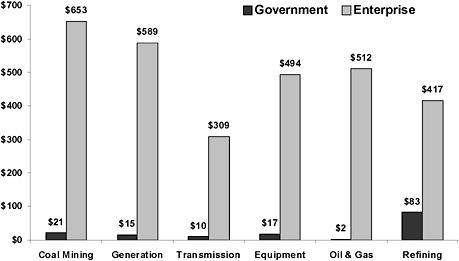

Trevor Houser, a director at China Strategic Advisory, discussed Chinese energy use and Chinese energy R&D (Figure 11). He noted that in 1980 the entire Chinese energy sector was controlled by the government; without any profit motive at work, investment was based purely on government plans. Since then much of the energy sector has been turned over to private corporations, resulting in large gains in efficiency. China’s energy intensity today is only one-third of what it was in 1978. On the other hand, the private operators of energy companies have no incentives to limit emissions.

The demand for energy in China is increasing at a phenomenal rate, Houser noted. Currently China has about 680 gigawatts of installed generating capacity, much of it added very recently. About 100 gigawatts was brought on line two years ago and another 100 gigawatts

FIGURE 11 Chinese spending on energy R&D ($ millions, 2004) SOURCE: Houser

last year. It is projected that by 2020, China will have installed another 1000 to 1300 gigawatts of capacity. To put that in perspective, the total current generating capacity of the United States is now about 900 gigawatts.

“When you have power demand growing that fast, it creates challenges for innovation because you are trying to throw whatever you have on the grid as quickly as possible,” Houser observed. Large-scale blackouts in 2004 and 2005 pushed China to add power as quickly as possible, with very little investment in R&D and reliance instead on the technology most familiar to Chinese energy companies—pulverized coal. The Chinese power industry has become very adept at building coal-fired power plants in a period of shortage, taking about six months from start to finish. Last year, coal accounted for 90 of the 100 gigawatts added by Chinese power producers, with hydro and wind accounting for the remainder.

The future will look very similar, Houser said, although Chinese companies are trying to diversify their power generating capacity somewhat. For example, China will add about 40 gigawatts of nuclear power over the next 15 to 20 years, making the country the largest nuclear power market in the world; but nuclear power will account for only 3 to 4 percent of the total installed capacity in 2020. Initially, the nuclear technology will be supplied by Westinghouse, which will build several nuclear plants and then transfer the technology to local companies that will build that next thirty plants.

Hydroelectric power is the major hope for meeting China’s goal of supplying 15 percent of its energy demand with renewable sources by 2020, Houser said. The plan is to have 240 gigawatts of hydro power by then, but that is the equivalent of building a new Three Gorges Dam every two years, which may not be politically feasible. Natural gas will be used to a certain extent in power generation, but it is needed for other purposes, such as feedstock in chemical plants and for household uses. Thus coal will continue to be the source of a large majority of

the country’s power for the foreseeable future.

Because China will account for so much of the world’s new power generation capacity over the next couple of decades, according to Houser, the innovation choices made in China will be crucial not just for that country but also for the rest of the world. He suggested that it is crucially important to get the incentives for cleaner technologies right in China because the country’s huge market and position as a global manufacturing base for energy technology. If China builds a large amount of capacity with wind power, for example, world prices for that technology will drop significantly. But the same is true of dirtier technologies such as pulverized coal. Costs will go down, encouraging increased worldwide use.

Lifeng Zhao of Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government spoke on prospects for clean coal technologies under development in China. Agreeing with Houser that coal will dominate China’s energy needs for the next few decades, she said that as a result, China is focusing a great deal of attention on clean coal technologies.

A number of agencies in China are funding a variety of approaches to clean coal technology, Zhao said. A great deal of attention is being paid to increasing efficiency, for instance, and to various pollution control technologies. New coal-fired plants are being equipped with flue gas desulfurization (FGD) units, and existing plants will need to be retrofitted with the FGD units to meet standards on emissions of sulfur dioxide. New plants are also setting aside space for future flue gas denitrification equipment installations, and emission standards are being prescribed for nitrogen oxides.

The Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology is supporting R&D efforts in a number of coal technologies, including circulation fluidized boiler (CFB) plants, which are high efficiency and low polluting; ultrasupercritical pulverized coal power generation technology, which is also high efficiency but has back-end clean-up to keep emissions at a minimum; integrated gasification combined cycle plants, which can be almost as clean as plants burning natural gas; and coal gasification and liquification technologies. Some of these technologies have already been put to work in China, Zhao said. In April 2005 China opened a 300-megawatt CFB plant made with imported technology and equipment; and in June 2006 it started up a 300-megawatt CFB plant that was made domestically. More than ten other 300-megawatt CFB plants are currently under construction. Other innovative coal technologies being explored in China are direct hydrogen production from coal and simultaneous carbon dioxide control and removal of gaseous pollutants during coal combustion.

Finally, Zhao noted, even though China is going to be heavily dependent on coal for the foreseeable future, there is still room for innovation in other sectors—nuclear, wind, and solar cell technology, among others—and other countries should be thinking of China as a market for innovative technologies in these areas.