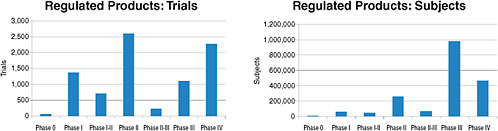

FIGURE 2-3 Number of the 8,386 clinical trials involving FDA-regulated products and 1.9 million study subjects being sought for these trials by phase of research.

SOURCE: Krall, 2009. Reprinted with permission from Ronald Krall 2009.

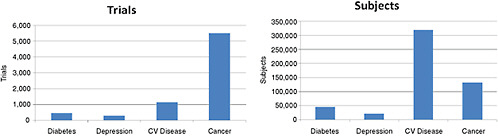

FIGURE 2-4 Number of the 10,974 ongoing clinical trials and 2.8 million study subjects being sought by disease being studied. NOTE: CV Disease = cardiovascular disease.

SOURCE: Krall, 2009. Reprinted with permission from Ronald Krall 2009.

compared with 20 patients per cancer trial, 70 patients per depression trial, and 100 per diabetes trial.

THE CLINICAL INVESTIGATOR WORKFORCE

Annual surveys from the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development indicate a consistently high turnover rate in the clinical investigator community. Investigators conducting a clinical trial to support a New Drug Application (NDA) or a change in labeling are required to complete FDA’s Form 1527. In 2007, 26,000 investigators registered this form with the FDA, 85 percent of whom participated in only one clinical trial. The issues facing clinical investigators were discussed throughout the workshop, and many participants echoed the theme of the Tufts data—it is difficult to conduct clinical trials in the United States and establish a career as a clinical investigator. While opportunities in clinical investigation can vary depending on whether or not an investigator is working in private practice or academia, for example, the challenges to successfully conducting a clinical trial in the United States are substantial. Making clinical investigation an attractive career option for academics and professionals was mentioned by a number of participants as an important component of any approach to improving the capacity of the clinical trials enterprise in the United States.

Globalization

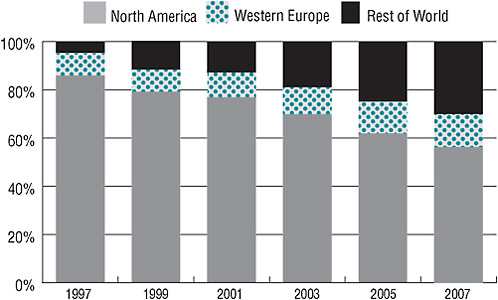

In addition to high turnover, the U.S. clinical investigator workforce is subject to an absolute decrease in its ranks. While there has been an annual decline of 3.5 percent in U.S.-based investigators since 2001, there has been an increase in investigators outside the United States. Figure 2-5 reveals that investigators from the rest of the world increased steadily between 1997 and 2007, making up for the decline in North American investigators over the same period. As of 2007, U.S. investigators constituted 57 percent of the global investigator workforce, a decrease from approximately 85 percent in 1997. According to the Tufts data, there are an estimated 14,000 U.S. investigators, compared with an estimated 12,000 investigators outside the United States. Currently, 8.5 percent of investigators are from Central and Eastern Europe, 5.5 percent from Asia, and 5.5 percent from Latin America.

Finally, Krall noted the difference between the role of a clinical investigator (i.e., the person who establishes the hypotheses to test, designs the trial, analyses and reports the results) and that of the individual who finds patients to participate in a trial and collects information about them. The latter role is essential to the ability to carry out research and should be recognized, rewarded, and developed to a greater degree, according to

FIGURE 2-5 The proportion of clinical investigators from North America has decreased since 1997, while the proportion of investigators from Western Europe and the rest of the world has increased.

SOURCE: Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development. 2009. Impact Report Jan/Feb; Current Investigator Landscape Poses a Growing Challenge for Sponsors. 11(1):2. Reprinted with permission from Kenneth Kaitin.

Krall. Workshop presenters and participants echoed Krall’s sentiment later in the day by discussing the many different levels of staff, in addition to the principal investigator, that ultimately make a clinical trial successful.

CAPACITY OF THE CLINICAL RESEARCH ENTERPRISE

KMR data from 2006 for the 15 largest pharmaceutical companies show that the majority of patient visits associated with an industry-sponsored clinical trial occur outside the United States. According to Krall, this statistic speaks to the costs and difficulty associated with conducting clinical research in the United States. In terms of cost-effectiveness, 860 patient visits occur in the United States per $1 million spent on clinical operations, whereas for the same cost, 902 patient visits occur outside of the United States. Thus, by the measure of cost per patient visit, U.S.-based clinical trials are not as cost-effective as those in the rest of the world. Krall urged caution in interpreting these data, however, given the high degree of variability among pharmaceutical companies in patient visit and cost measures.

U.S. investigators enroll two-thirds as many subjects into clinical trials as investigators in the rest of the world. Among U.S. investigators participating in a clinical trial, 27 percent fail to enroll any subjects, compared with 19 percent of investigators elsewhere. Investigator performance in the United States and the rest of the world is similar in that 75 percent of investigators fail to enroll the target number of subjects; also, 90 percent of all clinical trials worldwide fail to enroll patients within the target amount of time and must extend their enrollment period. Krall commented that these data on patient enrollment are from one pharmaceutical company but that, based on his industry experience and conversations with colleagues from other companies, he believes the data are generally consistent with the pharmaceutical industry as a whole.

According to clinicaltrials.gov data, clinical trials today call for the enrollment of 1 in every 200 Americans as study participants. Because this is such a remarkable undertaking, Krall questioned whether this high level of human participation is being put to the best use possible—that is, are the right questions being asked through the thousands of clinical trials being conducted today?

3

Challenges in Clinical Research

Cooperation among a diverse group of stakeholders—including research sponsors (industry, academia, government, nonprofit organizations, and patient advocates), clinical investigators, patients, payers, physicians, and regulators—is necessary in conducting a clinical trial today. Each stakeholder offers a different set of tools to support the essential components of a clinical trial. These resources form the infrastructure that currently supports clinical research in the United States. Time, money, personnel, materials (e.g., medical supplies), support systems (informatics as well as manpower), and a clear plan for completing the necessary steps in a trial are all part of the clinical research infrastructure. A number of workshop participants lamented that most clinical trials are conducted in a “one-off” manner.1 Significant time, energy, and money are spent on bringing the disparate resources for each trial together. Some workshop attendees suggested that efficiencies could be gained by streamlining the clinical trials infrastructure so that those investigating new research questions could quickly draw on resources already in place instead of reinventing the wheel for each trial.

This chapter summarizes workshop presentations and discussions focused on the challenges facing clinical research today. The first three challenges reflect broad, systemic issues in clinical research: (1) prioritizing of clinical research questions, (2) the divide between clinical research and

clinical practice, and (3) the globalization of clinical trials. Issues of paying for clinical trials and the narrow incentives for practitioners to participate in clinical research are then discussed. Finally, the chapter turns to the challenges of a shrinking clinical research workforce, the difficulties of navigating administrative and regulatory requirements, and the recruitment and retention of patients.

PRIORITIZING OF CLINICAL RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Fewer than half of all the medical treatments delivered today are supported by evidence (IOM, 2007), yet the United States lacks a clear prioritization of the gaps in medical evidence and an allocation of clinical research resources to efficiently and effectively fill these evidence gaps. The federal government, industry, academic institutions, patient advocacy organizations, voluntary health organizations, and payers each have incentives to develop research questions that suit their unique interests. The value of a particular research effort is judged by stakeholders according to their own cost–benefit calculation. Reflecting the diversity of stakeholder value judgments, and in the absence of a broad national agenda, clinical trials are conducted in a “one-off,” narrowly focused fashion.

Because clinical trials are necessary to obtain regulatory approval in the United States, they are a high priority to companies. It was noted by a number of workshop participants that the prioritization of clinical research questions by companies seeking regulatory approval is distinctly different from the priorities of society in general, which may prioritize the comparison of two commonly used therapies. This divergence between the priorities of society and industry is notable as the nation discusses how to address the current gaps in clinical research and medical decision making.

As an example, in investigator-initiated research, academic investigators seek federal funding (primarily from the National Institutes of Health [NIH]) to conduct research they deem important to advancing science and/or medical practice. But James McNulty, Vice President of Peer Support for the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (DBSA), believes the NIH peer review process for research grants is inherently conservative and fails to reward innovative research into areas about which little is known. McNulty believes this conservative approach has contributed to serious gaps in knowledge in the area of mental health, specifically in schizophrenia, depression, and bipolar disorder. In terms of formulating relevant research hypotheses, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) was cited as one example of a health system that successfully engages practicing physicians in noting potential research questions that arise in the day-to-day care of patients. The VA Cooperative Studies Program works to ultimately take physicians’ questions into the clinical trial setting.

Industry-sponsored trials are conducted largely to gain U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval to market a new drug or a previously approved drug for a new indication. Preapproval trials include a simple protocol (i.e., ask a limited number of questions) and test a drug in a highly selected patient group designed to provide the most robust evidence on the drug’s benefits and risks. Conversely, the federal government conducts large clinical trials to answer medical questions unrelated to gaining regulatory approval for a new drug or therapy. These studies can involve a wide range of patients and seek to answer a number of relevant clinical questions at once. Several presenters in the diabetes session of the workshop suggested that government-funded clinical trials for diabetes would not be conducted by industry or other sectors. New therapies for type 1 diabetes are often of limited interest to pharmaceutical companies because of the small patient population, whereas drugs for the exponentially larger type 2 diabetes population are avidly pursued.

The beginnings of a coordinated prioritization of research needs can be seen in the recent increased interest in comparative effectiveness research (CER). To enhance the ability of clinical research to generate knowledge that can better inform clinical practice, Congress included in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009 an allocation of $1.1 billion for federal agencies (the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], NIH, and the Department of Health and Human Services [HHS]) to jumpstart the national CER effort. CER seeks to identify what works for which patients under what circumstances, providing evidence about the costs and benefits of different medical options. One-third of ARRA funds ($400 million) were designated as discretionary spending by the Secretary of HHS to accelerate CER efforts. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) was tasked with recommending national CER priorities to be supported with these discretionary funds and to guide the nation’s creation of a long-term, sustainable national CER enterprise.2 Recently enacted health care reform legislation (Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act passed in March 2010) created the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)—a nonprofit institution positioned outside the federal government to define and execute comparative effectiveness research methods.

Several speakers and workshop participants raised questions about the ability of the current clinical trials system, which is already showing signs of strain, to absorb a substantial amount of the anticipated CER studies. Many voiced concern regarding the overall organization of clinical research in the United States: how it is prioritized, where it is conducted, who oversees it, how it is funded, who participates, and who staffs it. Presenters and

|

2 |

A list of initial national priorities for CER recommended by the IOM in 2009 can be found at http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2009/ComparativeEffectivenessResearchPriorities.aspx. |

participants also described the diminished capacity of the current clinical trials system. These observations, and proposed solutions, informed the discussion over the course of the 2-day workshop.

THE DIVIDE BETWEEN CLINICAL RESEARCH AND CLINICAL PRACTICE

Janet Woodcock, Director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), identified bridging the divide between research and the clinical practice of medicine as one of the most critical needs facing the clinical research enterprise today. The limited involvement of community physicians in clinical research reduces physician referrals of patients to clinical research studies, as well as the total number of investigators available to conduct the research (see the discussion of narrow incentives for physician participation in clinical trials below). Furthermore, the findings of research conducted in academic medical centers rather than in community settings are less likely to be adopted by physicians in their daily practice. The poor rate of adoption of effective clinical practices is reflected in one study that examined adherence to 439 indicators of health care quality for 30 acute and chronic conditions and preventive care. Results indicated that American adults receive on average only 54.9 percent of recommended care (McGlynn et al., 2003).

Woodcock stressed that, to generate relevant research based in clinical practice, community practitioners must be actively involved in the clinical trial process. She suggested it is not surprising that the uptake of evidence-based practices is slow when practitioners are not engaged in the research that supports the changes. In many instances, the characteristics of the study population, their comorbidities and therapeutic regimens, and the setting and conditions under which the trial is conducted bear little resemblance to typical community practice. Indeed, the outcomes are often quite different as well. It is little wonder that community physicians may be hesitant to modify their treatment practices to reflect clinical findings developed in this manner. According to Woodcock, the divergence between physicians conducting research and those in community practice is one of the greatest barriers to successfully translating study results into clinical practice. She argued that, to develop a truly learning health care system capable of self-evaluation and improvement, the currently separate systems of clinical research and practice must converge.

Challenges Facing Investigators in Academic Health Centers

Woodcock discussed a number of important obstacles facing investigators conducting research using the current infrastructure. Clinical investi-

gators, those who lead a research idea through the clinical trial process, face multiple small obstacles that together can appear insurmountable. These obstacles include locating funding, responding to multiple review cycles, obtaining Institutional Review Board (IRB) approvals, establishing clinical trial and material transfer agreements with sponsors and medical centers, recruiting patients, administering complicated informed consent agreements, securing protected research time from medical school departments, and completing large amounts of associated paperwork. As a result of these challenges, many who try their hand at clinical investigation drop out after their first trial. Especially in the case of investigator-initiated trials, where an individual’s idea and desire to explore a research question are the primary force behind the trial, the complex task of seeing a clinical trial through from beginning to end is making the clinical research career path unattractive for many young scientists and clinicians. Woodcock noted that in her experience, successful clinical investigators represent a select subset of clinicians—highly tenacious and persistent individuals with exceptional motivation to complete the clinical trial process.

According to Robert Califf, Vice Chancellor for Clinical Research and Director of the Duke Translational Medicine Institute, some of the challenges to participating in clinical research mentioned by clinical cardiovascular investigators include

-

the time and financial demands of clinical practice;

-

the overall shortage of cardiovascular specialists;

-

the increasing complexity of regulations;

-

the increasing complexity of contracts;

-

the lack of local supportive infrastructure;

-

inadequate research training;

-

less enjoyment from participation (e.g., increasing business aspects, contract research organization pressures); and

-

data collection challenges (medical records, reimbursement, quality control, pay for performance).

Califf noted that most of these challenges do not involve the actual conduct of a clinical trial and that many investigators say it is not difficult to get patients to participate in trials as long as the critical physician–patient interaction takes place. Investigators also cite the importance of support for research efforts from their home institution.

Challenges Confronting Community Physicians

Practitioners face a number of challenges to their involvement in clinical research. Busy patient practices and the associated billing and reporting

requirements leave them with limited time for research. A further barrier is the lack of a supportive clinical research infrastructure, especially in the form of administrative and financial support. For practitioners who become engaged in running a clinical trial and recruiting patients, their financial reimbursement per patient can, in some cases, be less than they would receive from regular practice. In addition, there is a financial disincentive for physicians to refer their patients to clinical trials. Physicians who do so must often refer those patients away from their care; thus each patient referred represents a lost revenue stream.

Challenges Facing Patients

Patients also face challenges to participating in clinical research. Many workshop participants noted that patients often are unaware of the possibility of enrolling in a clinical trial. If they are aware of this opportunity, it is often difficult for them to locate a trial. Patients may reside far from study centers; even the largest multicenter trials can pose geographic challenges for those wishing to participate. Moreover, depending on the number of clinic visits required by the study protocol, significant travel and time costs may be associated with participation. In addition, trials designed with narrow eligibility criteria for participation purposely eliminate many patients who might have the disease being studied but are ineligible because of other characteristics (e.g., age, level of disease progression, exposure to certain medicines).

As noted, trials often require patients to temporarily leave the care of their regular doctor and receive services from unfamiliar providers. In addition to confronting potentially undesirable interruptions in care, it is understandably difficult for many patients to justify the physical and emotional strain of leaving their regular provider to volunteer for a clinical trial. If a patient reaches the point of enrolling in a clinical trial, the extensive paperwork associated with the informed consent process can be confusing and burdensome. As discussed later, informed consent forms are developed to meet legal requirements and can contribute to the confusion patients feel regarding the trial and what it entails. In addition, there is sometimes a mistrust of industry-sponsored trials among the public. These feelings of mistrust can further complicate the already difficult decision about whether to join a trial.

GLOBALIZATION OF CLINICAL TRIALS

The increasing trend toward conducting clinical trials outside the United States is an important consideration in discussing ways to improve the efficiency of trials. The number of patients enrolled in clinical trials

is decreasing in the United States and increasing abroad. According to Woodcock, when development programs are conducted entirely outside the United States, the FDA questions the extent to which the results can be translated to U.S. clinical practice. The applicability of foreign trials results depends on the disease being studied and the state of current clinical practice in that area.

Califf suggested that the difficulties inherent in conducting clinical trials in the United States have contributed to the relative decline in U.S. clinical trials described in Chapter 2. Citing a recent paper that he coauthored, he noted that one-third of phase III trials for the 20 largest U.S. pharmaceutical companies are being conducted solely outside the United States (Glickman et al., 2009). For these same firms and studies, a majority of study sites (13,521 of 24,206) are abroad (Glickman et al., 2009). Califf stated that the situation is the same across study sponsors—NIH, industry, and academia all look to conduct trials internationally.

Califf suggested that globalization is a positive trend overall, one in which he and his home organization, the Duke Clinical Research Institute (DCRI), are engaged. However, the current situation in which clinical research is being sent abroad just to get trials completed is unsustainable. One reason for this situation is that clinical trials in a number of other countries cost less than they currently do in the United States (Table 3-1) (see also the discussion of costs below). If a large outcome trial requires enrolling tens of thousands of patients, for example, selecting trial sites in Russia or India instead of the United States can result in hundreds of millions of dollars in savings. The overall cost associated with gathering the necessary resources to conduct a clinical trial is an important factor in the choice of a trial site. For instance, physician salaries in a number of countries are lower than in

TABLE 3-1 Global Research Costs: Relative Cost Indexes of Payments to Clinical Trial Sites

|

Country |

Cost of Clinical Trials Relative to the United States |

|

United States |

1.00 |

|

Australia |

0.67 |

|

Argentina |

0.65 |

|

Germany |

0.50 |

|

Brazil |

0.50 |

|

China |

0.50 |

|

Russia |

0.41 |

|

Poland |

0.39 |

|

India |

0.36 |

|

SOURCE: Califf, 2009. |

|

the United States. In these countries, the charges to clinical trial sponsors for conducting a clinical trial with physician involvement are lower than they would be in the United States. Some also argue that clinical trials conducted outside of the United States are of higher quality because of better adherence to trial protocols and better patient follow-up.

THE COST OF CLINICAL TRIALS

Clinical trial costs can vary widely depending on the number of patients being sought, the number and location of research sites, the complexity of the trial protocol, and the reimbursement provided to investigators. The total cost can reach $300–$600 million to implement, conduct, and montor a large, multicenter trial to completion. Table 3-2 outlines the various costs of an exemplar large, global clinical trial, which in this case add up to about $300 million.

Christopher Cannon, senior investigator in the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Study Group, stated that two clinical trials on which he is working cost a total of $600 million. To put this cost in perspective, it represents approximately half of the $1.1 billion allocated for comparative effectiveness research in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. According to Cannon, the exorbitant cost of clinical trials today points to the need to move toward simpler large trials that would study a broader population, include less data, and cost less overall.

The federal government funds a large portion of clinical research in the United States, primarily through NIH. In some cases, it has been estimated that NIH institutes pay research sites 20–40 percent less than the actual cost of conducting trials. Michael Lauer, Director of the Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI),

TABLE 3-2 Breakdown of the Costs for a Large, Global Clinical Trial (14,000 patients, 300 sites)

|

Expense |

Cost (in millions of $) |

|

Site payments |

150.0 |

|

Monitoring |

90.0 |

|

Data management and statistics |

12.0 |

|

Project and clinical leadership |

12.0 |

|

Interactive voice response systems (IVRS) and drug distribution |

10.8 |

|

Publications |

.1 |

|

Total |

~300 |

|

SOURCE: Califf, 2009. |

|

National Institutes of Health, responded that to remedy the issue of appropriate NIH payments to research sites, the solution will likely involve a combination of increasing the amount of money paid by NIH to sites and decreasing the charges associated with conducting the research. Lauer further explained that because NIH’s funding is relatively flat, if research site payments are increased, an equivalent decrease in funding in other areas will be necessary. Given this zero-sum calculation, it will be politically difficult to increase payments for research sites. Lauer believes that simplifying trials could be most effective in reducing their cost. He suggested that good science comes from high-quality observations that are followed by focused experiments to test these observations. The trials that have had the greatest impact on clinical decision making and patient care have been simple (e.g., uncomplicated study protocols, short case report forms). Thus, if the research community could keep trials simple and large enough to answer the study question(s), costs could decrease, while the impact and relevance of the results would increase.

Workshop participants also discussed the inequality of NIH payments to research sites across the various NIH institutes. This variation has created a scenario in which some institutes that pay research sites more are seen as the “haves,” while those that pay less are seen as the “have-nots.” Judith Fradkin, Director of the Division of Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Metabolic Diseases in the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) at the National Institutes of Health, noted that inconsistency across Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) institutions in the level of clinical trial support they provide makes it difficult for NIH to determine how its payments to research sites should be adjusted to take CTSA support into account.

NARROW INCENTIVES FOR PHYSICIAN PARTICIPATION IN CLINICAL RESEARCH

As discussed earlier, the current clinical research enterprise in the United States is largely separate from traditional clinical practice. In part because the United States does not have a nationalized health care system in which services are provided to all citizens through government-funded providers, clinical research takes place in various types of sites, frequently outside of the community-based, primary practice setting where most patients receive care. Moreover, as noted above, private practice physicians have disincentives to refer their patients to clinical trials. The fewer physicians are involved in developing and implementing clinical trials, the less scientific the practice of medicine will be. A number of workshop attendees suggested that a mechanism to adequately compensate physicians for referring patients to clinical trials could improve recruitment rates of U.S. patients.

Making it easier for community-based physicians to participate actively in clinical trials could also have a positive effect on patient recruitment; enhance the engagement of the community in important research; and increase the chances that physicians will change their practice behavior based on research results they were involved in generating, thereby strengthening the trend toward evidence-based medicine in the United States. Workshop participants also suggested that, to encourage physician participation in clinical trials, the study questions and protocol should be designed in the context of clinical practice—that is, the procedures required by a trial protocol should be easily incorporated into practice.

It is also important to consider that the research questions clinical trials seek to answer reflect the incentives and interests of those developing the questions. In this respect, the capability of the health care system to act on trial results is part of the clinical research decision making process. For instance, Amir Kalali, Vice President, Medical and Scientific Services, and Global Therapeutic Team Leader CNS (central nervous system), at Quintiles Inc., explained that his company ran the two largest clinical trials testing the combination of psychotherapy and medication to treat depression. Despite scientific evidence for the benefits of psychotherapy, it has seen limited uptake. According to Kalali, this is because patients have limited access to psychotherapy as a medical treatment in the United States. Thus, the capability of the health care system to implement or act on research findings can be an important consideration in conducting clinical trials to test alternative treatments for a condition.

SHRINKING CLINICAL RESEARCH WORKFORCE

Research involving human subjects has become an increasingly complex environment in which to work and be successful. Thus, it is not surprising that, as noted in Chapter 1, the clinical investigator workforce is plagued by high turnover. Clifford Lane, Clinical Director, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), shared data from NIAID revealing the trend that fewer professionals are entering the research field than in the past. As Figure 3-1 indicates, the number of tenure-track principal investigators conducting research within the NIAID/NIH intramural program decreased from 74 in 2003 to 42 in 2008. While there was a slight increase to 53 tenure-track investigators in 2009, this number is still well below that in 2003.

The majority of phase III clinical trials are conducted by extramural researchers. However, trends in intramural NIH programs add to our general understanding of the issues and challenges facing investigators today. Lane commented that the overall decrease in intramural investigators is due in part to the fact that more researchers are turning to laboratory work be-