5

Transforming Discovery to Impact: Translation and Communication of Findings of Women’s Health Research

The previous chapters document substantial progress in research on women’s health. This chapter examines first the factors that shape translation of research findings on women’s health into use by health-care providers and public-health practitioners and, second, how those factors shape communication of research findings to women. The chapter closes with case studies of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), breast and cervical cancer and cardiovascular disease (CVD) to illustrate successes of—or obstacles to—translation into improvements in women’s health and communication of research findings to women. The information in this chapter addresses questions 5 and 6 in Box 1-4, which deal with whether research findings are being translated in a way that affects practice and whether they are being communicated effectively to women.

Many of the barriers to the translation and communication of research findings are similar between women’s and men’s health. Those barriers have been reviewed in other Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports (2001a,b, 2002a, 2006a,b), and their analysis is beyond the scope of this report. In this chapter, the committee highlights the issues that it considered especially relevant to women’s health.

TRANSLATION OF FINDINGS INTO PRACTICE

The steps in translation, communication, and application of research findings into practice and policies that lead to health improvements are complex. Each step involves different and sometimes competing factions—patients, providers, payers, purchasers, and manufacturers—and multiple processes. There are questions regarding who should transmit research information (investigators, government, industry, or the press), what the message should be (complex information or basic

elements), how the message should be framed (regarding an individual or a population), how the information should be transmitted (in scientific publications or by professional organizations, medical practitioners, or the mass media), who the target audience of the message is (health-care providers, women, or both), who uses the information, and, ultimately, what the individual woman, does with the information (Bero et al., 1998; Berwick, 2003; IOM, 2001a; Kreuter and Wray, 2003; Rogers, 1995).

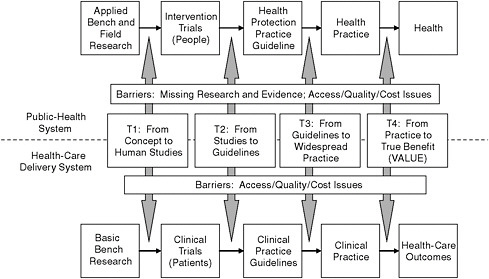

The steps in translating research discoveries into practice are outlined in Figure 5-1. The initial step generally occurs with the publication of results in peer-reviewed scientific journals. For some topics, the news media may immediately report the findings, as in the coverage of the WHI. If research findings will affect clinical practice, professional societies may develop clinical-practice guidelines. At each step, constraints associated with current practices limit the translation of findings into improved services. In cases where there are uncertainties or contradictory research findings, guidelines from different organizations can differ or updated guidelines might reflect recent data and contradict previous guidelines, leading to confusion. For example, if research findings are not analyzed or presented separately for women and men, this might decrease their utility in addressing women’s needs, including the development of women-specific

FIGURE 5-1 The process for translating research into practice. The top half of figure shows the path for a public-health system. The bottom half shows the path for health-care delivery systems.

SOURCE: Modified from a presentation by Dr. Julie Gerberding to the House Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies, March 5, 2008.

guidelines. Although there are exceptions, such as the women-specific guidelines for CVD issued by the American Heart Association (AHA) (Mosca et al., 2004a), most practice guidelines are not sex specific.

Government agencies and professional organizations play an important role in the translation of research findings into policy and practice. For example, in light of findings from the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial showing that tamoxifen reduced the incidence of invasive breast cancer in women at high risk for the disease (Cuzick et al., 2003; Fisher et al., 1998; Lewis, 2007; Mamounas et al., 2005; Powles et al., 1998; Veronesi et al., 1998, 2007), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required modification of the language on the label for tamoxifen (FDA, 1998). Government agencies and professional organizations have also developed campaigns to disseminate research findings to both health-care providers and women. For example, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office on Women’s Health (OWH), and AHA collaborated to develop the Heart Truth campaign to increase women’s awareness of their risks of heart disease (HHS, 2010). The campaign has contributed to an increase in awareness compared with that in 1997 (Christian et al., 2007; Mosca et al., 2010).

Barriers Associated with the Nature of Science

Clinically useful findings are almost never generated by a single study but require a multitude of studies of types—basic, clinical, and applied—and require the overall evidence to lay the foundation for a given clinical action. Along the way, different studies may produce dissimilar results. Beyond the uncertainty due to inconsistent findings, uncertainties about the applicability of findings and about inadequate data on the effects of treatments in women can occur when data are not analyzed and reported by sex. Failure to report sex-specific findings has resulted in delays in standard-of-care treatment for women, such as the use of stents, beta blockers, and aspirin for myocardial infarction (Berger et al., 2009; Chauhan et al., 2005; Lansky et al., 2005; Rich-Edwards et al., 1995).

Paradoxically, there are also examples of rapid adoption of unproven interventions, such as transplantation of autologous bone marrow for advanced breast cancer, which was later shown by research not to provide benefit but to increase risk (Farquhar et al., 2003; Rettig et al., 2007). An objective research base with sex-specific information is critical both for the adoption of new approaches and to stop practices that are not beneficial and may actually be harmful.

Barriers Associated with Economic, Social, and Cultural Factors

Economic forces and other nonscientific factors may complicate the interpretation of scientific data and their translation into practice. Conflicts of interest can occur in the conduct of science and the publication of scientific information

(Jagsi et al., 2009; Lexchin and Light, 2006), including findings related to drugs used primarily or exclusively by women. The role of industry in funding research, interpreting results, writing papers, and presenting findings directly to providers and industry’s relationships with patient-advocacy organizations can introduce bias (Burton and Rowell, 2003; Herxheimer, 2003; Koch, 2003; Moynihan, 2003; Watkins et al., 2003).

Social and cultural values may also complicate the translation of research into practice. That is most clearly seen in relation to sexual and reproductive health. For example, the adoption of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, which could prevent the vast majority of cervical cancers, has been slowed, in addition to concerns of parents about safety,1 because of a number of nonscientific issues. An editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine looking at the HPV vaccine highlighted the issues of access to the vaccine, high cost, and concerns focused on purported interference in family life and sexual mores (Charo, 2007). It identified a variety of political efforts to forestall the creation of a mandated vaccination program, which was attacked as an intrusion on parental discretion and an invitation to teenage promiscuity. Other identified barriers to vaccination include misinformation, lack of knowledge, substandard provider–patient communication, parental concerns about the sexual implications of HPV vaccination, and concerns about the manufacturers’ influence (Charo, 2007).

The case of the HPV vaccine also demonstrates disparities in the translation of knowledge into health-care services for less-advantaged groups. Specific populations of women—such as those of lower socioeconomic status (SES), those who have low literacy level, illegal immigrants, and those who have language barriers—are likely to be more affected by social barriers or by a lack of knowledge about HPV and the vaccine. For example, the 2007 California Health Interview Survey indicates that 90% of non-Hispanic white women 18–50 years old had heard of HPV, compared with 69% of Latinas (California Health Interview Survey, 2010). Vaccination rates are also lower in Latinas (14.0 %) than in white girls (19.7%) 12–26 years old; the largest discrepancy is in those 19–26 years old: Latinas, 6.7%, and non-Hispanic white women, 14.3% (California Health Interview Survey, 2010). Some studies have examined attitudes toward the HPV vaccine among Latinas, but methodologic shortcomings limit the utility of their results, and the factors that contribute to Latina underuse of the HPV vaccine remain unknown.

Although new knowledge generally benefits the more advantaged to a greater extent, more advantaged women may also be more likely to receive new treatments that have not been thoroughly tested and can have adverse effects that are

discovered only after additional study. Use of hormone therapy is a case in point. Hormone therapy was prescribed more frequently to more affluent, educated women; those women were then at greater risk of developing breast cancer. A recent analysis of the decline in breast-cancer mortality seen after the publication of the WHI findings, which studies have attributed to the decreased use of hormone therapy (Chlebowski et al., 2009; Hausauer et al., 2009; Jemal et al., 2007; Krieger et al., 2010), showed that the greatest decreases in mortality occurred among white women over 50 years old who had estrogen-receptor–positive tumors and lived in counties that had higher mean incomes (Hausauer et al., 2009; Krieger et al., 2010). Smaller decreases were seen in women in other racial or ethnic groups and in poorer areas who were less likely to have been using hormone therapy in the first place (Hausauer et al., 2009; Krieger et al., 2010).

Barriers Associated with Health-Care Providers

The existence and characteristics of substantial problems in our health-care system have been the topic of a multitude of studies and IOM reports (IOM, 2000, 2002b, 2006a, 2009). The problems are not specific to women but constitute a serious barrier to the efficient and effective uptake of information to improve the treatment of women. US adults receive only about half the recommended care, and its quality varies significantly by medical condition. Fragmentation of health care also hinders translation and may be particularly problematic for women. Many women receive their primary care from obstetricians and gynecologists, and others are seen also by other primary-care providers (Bean-Mayberry et al., 2007a). In addition, given the higher rates of comorbidities and late-life illnesses in women than in men (Marcus et al., 2005), women’s health issues often encompass a broader array of conditions and comorbidities—such as mental health disorders, bone disorders, CVD, cancers, autoimmune disorders, and violence—in addition to reproductive issues. To have those health needs met, women must see multiple providers, who are often in different places and who do not communicate with one another about the care they are providing. In the current health-care system, it is difficult for women to receive comprehensive evidence-based care in one place.

The HHS OWH funded National Centers of Excellence in Women’s Health to address the issue and change the care model for women. The centers were established to provide a comprehensive model of health-care delivery for women and to encourage community outreach, stimulate research in women’s health, incorporate research findings into women’s health in the clinic and medical-school curriculum, and the provision of leadership positions for women in academic medicine (Goodman et al., 2002). Funding for the centers ceased, however, and without outside support there is a risk that they will not be maintained by academic medical centers (Goodman et al., 2002). Although the Department of Veteran Affairs has established similar centers for women’s health (Bean-

Mayberry et al., 2007b), such a model is not widely adopted in other settings. That is especially disappointing in light of the evidence from a survey that women who used the centers of excellence were more satisfied with their health care than comparison populations and that the centers were particularly successful in mammography and breast self-examination and in counseling services related to many of the important determinants of health discussed in Chapter 2, including smoking and violence against women (Goodman et al., 2002).

Barriers in the Health Systems and Health Plans

Health systems and health plans can play an important role in translating evidence-based practices and research advances into clinical practice through the use of public reporting mechanisms and payment incentives. A key example is the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), a set of publicly reported health-plan performance measures maintained by the National Committee for Quality Assurance. The measures are routinely collected by managed-care plans through a review of administrative claims data, provider chart abstraction, and member surveys to gauge plan quality, preventive-care services, prenatal care, acute-disease and chronic-disease management, and satisfaction with health plans and doctors (NCQA, 2010). The data are used by some commercial plans and by Medicaid and Medicare managed-care organizations, and plans are evaluated and accredited on the basis of their performance on HEDIS measures. Therefore, there are strong incentives for providers in health plans or networks to meet the standards of care. Although the HEDIS measures have been expanded in recent years to capture conditions that are specific to women more fully, many measures for conditions specific to women are still not included. Furthermore, sex-, race- and ethnicity-specific analysis is rarely conducted on HEDIS measures to investigate possible sex-based differences in care or differential care patterns by race and ethnicity (Bird et al., 2007; McKinley et al., 2002; Weisman, 2000). No comparable, reportable, and uniform data source exists for patients in fee-for-service arrangements, so less is known about the quality of care of women who use those services than about the care of women in managed care (McGlynn et al., 1999).

Reimbursement by government and private insurers influences the provision of services and may determine whether research findings are adopted in clinical practice (Trivedi et al., 2008). For example, although research findings supported the value of breast and cervical cancer screening, many women were not being routinely screened until the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–funded National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program expanded coverage to low-income uninsured women (Henson et al., 1996). In recent years, there has been increased interest in basing reimbursement on practices that have been demonstrated to be effective. Reimbursement decisions might require additional studies of the safety and effectiveness of new treatments, such as comparative-

effectiveness studies. Those studies would be more informative if they provided sex-specific analyses of the effectiveness of treatments.

Barriers in Patient Decision Making

Given the fragmentation of care described above, patients often have to coordinate their own care. Those who are seriously ill often have to make a cascade of decisions about their treatment, and even those who are well and who wish to maintain their health and optimize wellness have an array of possibilities. The increased research on women’s health has led to more knowledge about women’s health, which has translated into heightened awareness of conditions that affect women, the availability of more treatments for some conditions, more information on an expanded number of outcomes of given treatments, the ability to detect potential diseases at earlier stages, and a proliferation of clinical guidelines. Those developments represent progress, but the increase in information and alternatives can overwhelm women who are making decisions.

Most decisions made by patients and providers alike involve weighing options that have uncertain probabilities and anticipating how they will affect overall health and quality of life. Some studies help to clarify the probabilities or value of outcomes, but more often than not new research expands available options that have uncertain outcomes (O’Connor et al., 1999). Studies of decision making have shown that, counter intuitively, some people making choices who are given more options make poorer choices on the average and are less satisfied with their decisions than those who are given fewer options (Schwartz et al., 2002). Expanding options (whether for screening, diagnosis, or treatment) is generally advantageous, especially if these offer different mixes of costs and benefits. However, increasing the number of alternatives also increases uncertainty in decision making and can pose profound challenges for patients and providers. For example, the use of more sensitive tests for cervical cancer lowers the threshold for detecting cervical cancer, decreases specificity, and increases uncertainty about the likelihood of future disease and the benefits of intervention. In other words, a more sensitive test will detect abnormalities in the cervix that are less likely to develop into cervical cancer than are more advanced lesions. A positive test provides a woman and her physician with less information about the risk posed by the lesion than if the lesion had been detected at a more advanced stage (Sundar et al., 2005). The problems posed by uncertainty and multiple options should not preclude developing or offering alternatives or encourage limiting choice. Rather, awareness of the difficulties should foster more research on how best to present complex choices and highlight the need for clear explanations and decision aids for such decisions.

The increased knowledge about multiple end points that might be affected by a treatment decision (that is, if a treatment for one disease might not only decrease the risk of adverse consequences from that disease but also increase the

risk of other diseases) introduces additional challenges, including questions as to which end points are most important; how to weigh multiple end points, which might vary in severity, timing, and likelihood; and how to assess composite impact. For example, the WHI reported on dozens of outcomes. There are attempts to report on composite end points (such as the WHI “global index” and a similar index for tamoxifen), but there is no consensus on components of these indexes or their internal weighting (Sundar et al., 2005).

Advances in decision-making science over the last 2 decades provide greater understanding of the barriers to optimal decision making by both providers and patients. Patient preference is playing a larger role in treatment decisions through shared clinical decision making (O’Connor et al., 2007). Decision aids can facilitate communication between patients and providers concerning specific clinical decisions, make information about options and outcomes available, and clarify personal values (O’Connor et al., 1999). Decision aids are particularly helpful when there is no clear right or wrong decision and the evidence supporting different treatment options suggests equipoise. Such aids have proved to be effective, for example, in relation to decisions regarding treatments for breast cancer. In one study, Sepucha and colleagues (2002) randomized breast-cancer patients to an intervention that helped them to prepare for a consultation visit or to usual care. Patients who received consultation planning were more satisfied with their consultation, as were the physicians who treated women in the intervention group. Later studies have shown that those tools not only increase satisfaction but enhance communication and improve decision quality and that such practices can be institutionalized into clinical care, not only in the academic medical setting in which they were developed but in practices that serve rural women (Belkora et al., 2009; Franklin et al., 2009). More sophisticated computerized risk models that can account for many conditions that affect women (such as breast cancer, cervical cancer, and osteoporosis) have been developed and can be used as decision-making tools.

Developments Aimed at Speeding Translation

In women’s health, as in all elements of health, there is a large gap between research discoveries and their implementation into practices that result in better outcomes. Increased investment in health research in recent times has resulted in an explosion of discoveries. However, the serendipitous nature of translation and the barriers to the adoption of new discoveries are reflected in the 15–20 years that it typically takes for discoveries to be adopted into clinical practice (Bansal and Barnes, 2008). Several developments are working to speed the process.

One is the emphasis in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) on translational research. Policy makers, administrators, and scientists are increasingly considering how to translate basic-science discoveries at the molecular and animal levels into human-health applications at the clinical and population levels more

rapidly. NIH has funded Clinical and Translational Science Awards to medical research institutions to support consortia whose goal is to develop the infrastructure needed to speed translation of research from bench to treatment, from treatment to provider practice, and from provider practice to improved population health (NIH, 2010).

A second development is the emergence of the health-consumer advocacy movement, which has sought a more active role for laypersons in their own health care (Keefe et al., 2006). A number of advocacy groups are devoted to women’s health and have pushed for increased research and increased translation of research findings into practice, including groups advocating for research, treatment, and policy changes related to breast cancer and to heart disease in women (Kolker, 2004; Lerner, 2002). For example, the National Breast Cancer Coalition (NBCC) had as one of its main goals “increasing access to screening and treatment for all women.” The NBCC has been credited with ensuring congressional funding for the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program and the Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act of 2000, which provide funding, respectively, for breast- and cervical-cancer screening and for treatment for women who cannot afford to pay (Lerner, 2002). The NBCC is one of many groups that have contributed to an improvement in women’s health, either through the women’s health movement in general or through organizations related to specific conditions (Allsop et al., 2004; Keefe et al., 2006; Kolker, 2004).

Third, the movement toward evidence-based practice is creating demand for a more rigorous evaluation of new treatments. Research findings are necessary for evidence-based medicine that can be used to speed the adoption of effective and safe interventions while avoiding interventions that are less effective, ineffective, harmful, or more expensive (IOM, 2008). Pressures for evidence-based medicine arose, in part, from women’s experiences with drugs whose adverse health effects and efficacy were supported by inadequate data. Two examples are diethylstil-bestrol, which resulted in a rare form of vaginal cancer in the female offspring of women who used it while pregnant (Herbst and Anderson, 1990), and the WHI, which demonstrated that hormone therapy, which without proper trials had been in widespread use to reduce cardiovascular risk in women, was not effective in reducing cardiovascular risk and, in fact, increased the risk of breast cancer in women (Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators, 2002).

COMMUNICATION

Women are not passive recipients of care, but active participants in decision making (Braddock et al., 1997). To be effective in that role, however, women need access to clear and accurate information. That need highlights the importance of communicating scientific findings, which can often be complex, in simple, accurate, understandable, and actionable messages. Although a substantial literature provides information on the process of communication itself and on identifying

strategies that are effective in the diffusion and adoption of new information and approaches (Rogers, 2003), the findings are not explicitly developed in relation to the communication of research findings to women.

Women’s access to research findings and their capacity to use them to improve their health depend on a number of factors, including their SES, race, and ethnicity. Greater uptake of new information by those who have more advantages works to increase disparities when new data are available (Donohue et al., 1975; Viswanath and Finnegan, 1996).

Even when research results are delivered by reliable and objective sources, problems can emerge in communicating them. Some of the problems are derived from the complexity of results, which may generate confusion. An example is the recent statement released by the US Preventive Services Task Force on mammography screening. It reviewed extensive data on the appropriateness of mammography screening for women and on the balance between lives saved through early detection and adverse effects of false-positive results as these varied by age (discussed in case study below) (Nelson et al., 2009). One of the task force’s recommendations for women aged 40–49 was that “the decision to start regular, biennial screening mammography before the age of 50 years should be an individual one and take patient context into account, including the patient’s values regarding specific benefits and harms” (US Preventive Services Task Force, 2009). The main message received by the public, however, was that women aged 40–49 years should not routinely screen for breast cancer. Another example of the difficulty of disseminating research information, also discussed below, is the WHI, in which messages were communicated rapidly to women in the study but only later to physicians; there was thus a lag in the movement of complete information to clinicians who were receiving questions from and giving advice to female patients before they had it (Bush et al., 2007).

The Internet has added a powerful new dynamic to communicating information (Viswanath and Finnegan, 1996). About four-fifths of American adults use the Internet in their homes, offices, schools, or other locations (Harris Interactive, 2008a), and the population of Internet users increasingly looks like the population of the United States. Initially dominated by men, the population of Internet users is today equally divided between men and women. The Internet has become a common source of health information for people in general and for women in particular. Over 80% of Internet users said that they had looked on line for health information (Harris Interactive, 2008b). The Internet was the third-most frequent (46%) source of information that respondents reported turning to when facing a health problem, behind professionals (83%) and family and friends (51%) (Estabrook et al., 2007). Fewer people turned to print sources of health information (37%), television or radio (16%), government agencies (15%), and libraries (10%) (Estabrook et al., 2007).

Women have consistently engaged in more health-related online activities than men (Tu and Cohen, 2008). A 2006 survey found that 54% of health-

information seekers were women, whether they were acting as consumers, caregivers, or “e-patients” (Internet users who seek online health information that is of particular interest to them). The top health topics on which women sought information were specific diseases or medical problems (69%); medical treatments (54%); diet, nutrition, and vitamins (53%); exercise or fitness (46%); and prescription or over-the-counter drugs (39%). Women reported significantly more interest in online information than men about specific diseases, particular treatments, diet, and mental health (Fox, 2006). Another study found that women are more likely than men to look online for support groups to communicate about health conditions (Fallows, 2005).

There is evidence that Internet users, including women, find online health information to be helpful and use it to make decisions about their health. In one survey of e-patients, 31% said that they or someone they knew had been substantially helped by following medical advice or health information found on the Internet, whereas only 3% said that they or someone they knew had been seriously harmed by following advice found online (Fox, 2006). Women who have breast cancer use the Internet to access information about their condition, share experiences, and obtain support (Fogel et al., 2002; Klemm et al., 1998; Sharf, 1997).

As discussed earlier, however, more information is not necessarily better from the health consumer’s standpoint. Evidence is emerging that confusion about cancer in general may be having an adverse effect on the American public. In a cross-sectional analysis, Arora and colleagues (2008) found that of the 45% of American adults who had searched for cancer information on the Web, nearly three-fifths expressed concerns about the quality of information, nearly half reported negative experiences when searching for cancer information, and about two-fifths reported frustration in their searching. Compared with those who had a better experience, those experiencing such frustration were more likely to agree that “everything causes cancer,” that there are few actions a person can take to prevent cancer, and that it is hard to know what prevention recommendations to follow. Importantly those who had no more than a high-school education were more likely to report having an adverse experience and the other effects mentioned. As the Internet continues to transform how people receive health information and interact with their health-care providers, work is needed to address those concerns and frustrations.

CASE STUDIES IN TRANSLATION AND COMMUNICATION

The Women’s Health Initiative

Hormone therapy has been studied, prescribed, debated, hailed, and criticized for more than 70 years (Rymer et al., 2003). From the middle 1960s to 2002, hormone therapy for postmenopausal women (then called hormone-replacement therapy) was commonly prescribed not only for menopause symptoms but be-

cause of presumed health benefits, including prevention of chronic disease (Garbe and Suissa, 2004; Rymer et al., 2003). The WHI was designed as a primary prevention study that was, by many, anticipated to demonstrate the preventive effects of hormone therapy for postmenopausal women against CVD. For example, the design of the WHI was reviewed and critiqued by an IOM committee during the early phases of the study (IOM, 1993). One criticism made by the IOM committee was that the informed consent and “stopping rules” for the study were not explicit enough, with the major concern being that “[t]he emergence of new information that may require closing a branch of the [clinical trial] is not unlikely over the next nine years. One branch is at special risk: the near-term effects of hormones on reducing cardiovascular risk factors and event rates may be confirmed early in this project.” In July, 2002, when the WHI (see Appendix C for description) stopped its clinical trial of conjugated equine estrogen plus progestin (Prempro™) early (HHS, 2002a), many women’s and physicians’ opinions and perspectives of hormone therapy changed (Bush et al., 2007). The WHI results demonstrated that rather than reducing the risk of CVD, estrogen plus progestin therapy could increase the risk of CVD and the risk of breast and ovarian cancer (Schonberg et al., 2005). Once it was determined that the treatment could cause harm, the clinical trial was immediately canceled on the advice of a data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) after a mean of 5.2 years of study (HHS, 2002a).2 The DSMB determined that the increased risk of breast cancer and CVD (stroke and venous thromboembolic disease)—consistent with the results of the previous Heart Estrogen/Progestin Study—outweighed the benefit of lower risk of colorectal cancer and hip and osteoporotic fractures (Prentice and Anderson, 2008). In March of 2004 NIH informed participants of the estrogen-only hormone-therapy trial portion of WHI to stop taking the medication because of what it considered an unacceptable risk of stroke (HHS, 2004).

A search of Pubmed.gov for articles with “Women’s Health Initiative” in “All Fields” OR “hormone replacement therapy” as a MeSH term, limited to publication dates between July 9, 2002, and July 9, 2003,3 retrieved over 1,500 publications. Within a month of the announcement, 215 articles on the WHI findings were published in popular media (McIntosh and Blalock, 2005), and a study of local, regional, and national newspapers showed an 8-fold increase in the number of articles about hormone therapy the month after the stopping of the trial compared with periods before the announcement (Haas et al., 2006). A large number of women stopped hormone therapy almost immediately (Barber et al., 2004; Schonberg et al., 2005; Theroux, 2008). Filled prescriptions for hormone therapy dropped by 29%; and new prescriptions in 2003 and 2004 were 73% and

77% lower, respectively, than in 2001, and they were for different formulations from those in the WHI (Wegienka et al., 2006).

The response from physicians was uneven. A 2004 survey of a multidisciplinary group of health-care providers determined that 67% of the time respondents overestimated risks when hormone therapy increased risks and overestimated benefits when hormone therapy increased benefits (Williams et al., 2005). A study conducted in 2003 found that nearly half the physicians surveyed did not find the WHI results convincing enough to stop the clinical trial (Power et al., 2008). Physicians who had completed their residency more recently rated evidence from randomized clinical trials as more important, were more inclined to be favorable toward alternative therapies, and were most accepting of the trial results. In contrast, older physicians who had been in practice longer were unconvinced of the need to terminate the trial (Power et al., 2008).

Critiques of the WHI raise criticisms about which results were communicated and how. The stopping of the trial was based on relative risk; relative risk differs from attributable risk, which may not seem significant (Lobo et al., 2006) and which can overstate risk if it reflects “data-mining” (Bluming and Tavris, 2009). Another issue was generalizibility. Women in the hormone-therapy study were older and many years past the onset of menopause, so they had other health risks, such as the risk of atherosclerosis, which could have affected study results (Harman et al., 2005; Lobo et al., 2006). Sample selection is an issue in observational studies as well as in clinical trials. In addition to the fact that higher-SES women were more likely to be using hormone therapy, subjects in other hormone-therapy studies may have been affected by “healthy-user bias,” in that subjects were healthier, were better educated, had higher incomes, and were inclined to have better compliance than the general population (Harman et al., 2005). Observational studies of healthy users may have led to overestimation of expected benefits of hormone therapy in the WHI, which was a study of a population that was older, more obese, sometimes diabetic, and more often smokers than the women who were using hormone therapy at that time (Harman et al., 2005).

The WHI sample also underrepresented women for whom symptom relief would be a major benefit. Although the primary reason for hormone therapy in menopausal women is to treat for vasomotor symptoms (such as night sweats and hot flashes), the WHI focused on primary prevention of coronary heart disease, cancer, and fractures, and relief of menopausal symptoms was not included as a major end point (Prentice and Anderson, 2008). Women who had severe vasomotor symptoms were excluded from the study, probably to avoid having to randomize some of them to placebo (Lobo et al., 2006).

Women seek health information about hormone therapy from the mass media and health-care professionals. One study indicated that 48% go to health-care providers, 33% to print media, 29% to the Internet, 8% to social networks, and 5% to broadcast media (Breslau et al., 2003). Other reports have said that only 31% go to health-care providers for information on hormone therapy and that

the mass media are often primary and trusted sources of new information on hormone therapy (Theroux, 2005). The Internet provides a great deal of information, but it is also a venue for marketing pharmaceutical products, such as hormone therapy.

Some articles in scientific journals and in the popular press have been critical of the WHI and have cast doubt on the validity of its findings. Adding to the confusion about the value of and harm caused by hormone therapy are more recent allegations that pharmaceutical companies that produce hormone-therapy drugs influenced some of the publications that were critical of the study (Singer, 2009). That illustrates how the different goals and interests of science and industry may foster greater controversy and confusion.

The mass media played a large role in the dissemination of the findings of the WHI, which had worldwide ramifications. MacLennan and colleagues (2004) stated on the basis of a survey that most of the 64% of Australian women who stopped taking hormone therapy did so because of published reports. In a survey of Swedish women, “newspaper or magazines” and “television or radio” were the main sources of information for 43.8% and 31.7%, respectively (Hoffmann et al., 2005). In a very small study of 97 US women surveyed, all had heard about the WHI study, and 52% reported changing their use of hormone therapy in response (McIntosh and Blalock, 2005). In a study of women who received a mammogram at a site that is part of the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (327,144 women), “greater average household exposure to newspaper coverage about the results of the [estrogen plus progestion therapy arm of the Women’s Health Initiative] (EPT-WHI) was associated with a larger population-based decline in HT use after the publication of the EPT-WHI” (Haas et al., 2007). Among US women who received mammography and were surveyed by Kerlikowske and colleagues (2007), the decline in hormone therapy use was associated with exposure to newspaper coverage of the risks posed by hormone therapy. Taken together, those studies indicate that media coverage of the WHI affected women’s decisions regarding continuing that therapy.

After the WHI, women stated confusion and fear in making decisions about hormone therapy. Some women who could have benefited from hormone therapy stopped taking it or refused it for fear of increased risks of other health conditions. Other women who initially ceased hormone therapy began again but often with accompanying worry (French et al., 2006). Women stated that they would like to have their physicians more involved in the decision process (Theroux, 2005). Physicians observed that their patients were confused about hormone therapy and menopausal treatments and that they themselves would like more assistance, perhaps in the form of discussion or decision guides, in counseling patients (Bush et al., 2007; Lobo et al., 2006).

There are important lessons to be learned from the WHI experience. First, the surprising findings from the WHI emphasize the value of generating data

through objective research and using them as the basis of decisions in clinical practice. Such treatments as hormone therapy can affect multiple systems; if they are to be used for many years, long-term clinical trials are needed to gain data on their intended use. The data showed that what was then the practice of putting menopausal women on hormone therapy to prevent heart disease did not have this intended effect and in fact was harming them (Chlebowski et al., 2003). Later results confirmed that the health risks posed by long-term use of combination hormone therapy in healthy postmenopausal women persist even a few years after the drugs are stopped and clearly outweigh the benefits. About 3 years after women stopped taking combination hormone therapy, many of the health effects of hormones, such as increased risk of heart disease, were found to be diminished, but the risk of cancer remained elevated (Heiss et al., 2008).

The WHI demonstrated the value of a study design that included a variety of outcomes. Data on multiple end points allow a balancing of disease risks that may be increased, decreased, or unaffected by a given treatment. However, communicating findings that involve balancing benefits in relation to some outcomes and harm in relation to others is challenging. That problem arose in relation to the WHI and in the recent events surrounding guidelines for mammography. In both cases, the large response among women in general is indicative of how engaged women are on topics related to their health.

Cardiovascular Disease

CVD used to be thought of as a male disease, and this meant that less attention was paid to its impact on women. For more than a decade, there have been concerted efforts and calls to action by government agencies and private-sector not-for-profit organizations to reduce the burden of CVD in women through improved awareness, translation of research, and dissemination of information to the public and health-care providers. In 1997, an AHA scientific statement on CVD in women pointed to the growing number of women at risk (Mosca et al., 1997) and suggested that healthy lifestyles for young women should be emphasized, health-care providers should be sensitive to sex differences in CVD, scientists should examine potential sex differences in the pathophysiology of and outcomes related to CVD, research in minority-group women should be expanded, and education should play a pivotal role in communicating and translating scientific developments about women and heart disease. In that year, the AHA launched its national women’s heart disease and stroke campaign, highlighting the need for greater awareness of heart disease in women (Mosca et al., 2004b). The Red Dress symbol developed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Heart Truth campaign has become the national icon of the movement toward awareness of heart disease in women (Long et al., 2008).

The first initiative to develop female-specific recommendations to prevent

heart disease were published in 1999 and were based on a qualitative review of science, previous guidelines and consensus panel statements, and available gender-specific data (Mosca et al., 1999). The relative lack of data on CVD in women, however, limits the development of better guidelines for clinical care of women (Pepine et al., 2004). A report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality noted the paucity of women enrolled in diagnostic studies and stated that much evidence is based on research done in men (Grady et al., 2003), and an AHA consensus panel concluded that clinical decision making would be greatly improved if sex differences in cardiac-imaging technologies were better understood (Mieres et al., 2005). An expert panel representing a dozen national organizations updated the 1999 guidelines in 2004 and 2007, providing clinical recommendations based on a review and evaluation of gender-specific results of clinical trials (Mosca et al., 2004a, 2007). Hsia and colleagues (2010) applied the 2007 updated AHA guideline categories to the data from the WHI and found that the updated categories predicted coronary events with an accuracy similar to that of the Framingham risk categories.

Although physicians appear to be aware of CVD-prevention guidelines for women, implementation is less than optimal. A survey of randomly selected physicians (primary-care physicians, cardiologists, and gynecologists) found that perception of a woman’s risk was the primary determinant of adherence to preventive recommendations (Mosca et al., 2005). Gynecologists, two-thirds of whom reported providing primary care for their female patients, were less aware of national prevention guidelines and had lower self-reported effectiveness in managing risk factors than did the other physicians. Of concern was the finding that fewer than one-fifth of physicians knew that more women than men die of CVD each year and that in specific groups of women who have risk profiles identical with men’s, women were more likely to be assigned to a lower risk category than men (Mosca et al., 2005). As this example shows, simply releasing guidelines is not sufficient to change provider knowledge and practice; educational efforts aimed at health-care providers may be needed to improve translation of scientific results into practice.

Women themselves have become more aware of CVD: in 1997, only 30% of women recognized CVD as the leading killer of women, significantly less than the 57% and 54% of women who recognized CVD as the leading killer of women in 2006 and 2009, respectively (Mosca et al., 2010). In turn, greater awareness is linked to a greater likelihood of taking preventive action (Mosca et al., 2006). That association is more pronounced in racial- and ethnic-minority populations, and this suggests that targeted educational campaigns have the potential to reduce disparities in CVD outcomes in women.

Mammography

Mammography has an extensive history of scientific investigation, public and private extramural research funding, clinical care and practice guidelines, government regulations, public exposure in the mass media, confusion, and controversy. It illustrates the interaction of important public and private institutions and organizations, including the role of guidelines and government regulations, that shape the agenda for women’s health research and their knowledge, attitudes, and use of findings.

Competing Perspectives and Interests

In relation to any issue, those with different interests and concerns position themselves to build an agenda and shape the “frame” within which people will interpret information to which they are exposed (Hilgartner and Bosk, 1988; McCombs and Shaw, 1977, 1993). They compete in a symbolic “arena” for public attention. The communication media play a major role as gatekeepers to that arena (Gandy, 1982). Media attention, in conjunction with key social and institutional actors (such as news sources), raises, changes, or reinforces the public’s perception of the importance of issues (Corbett and Mori, 1999; Viswanath and Finnegan, 2002) and how the public thinks about them (Scheufele and Tewksbury, 2007).

Radiologic technology developed to a point where it was feasible and useful for routine screening for breast cancer in the late 1960s (Gold, 1992; Picard, 1998), and scientific and public controversy surrounding benefits of and risks posed by mammography have existed almost since then. The questions of the early 1970s centered on its promise as a new clinical tool and on the role that it should play for women at different levels of risk. By the middle 1970s, a scientific and clinical consensus was forming around the three-part approach to breast-cancer prevention: breast self-examination (BSE), breast clinical examination (BCE) by a trained health-care provider, and regular mammography for women over 50 years old and for younger women who have a family history of breast cancer (Foster and Costanza, 1984; Gorringe et al., 1978; Green and Taplin, 2003; Justin, 1977). The major clinical trials that would have provided an evidentiary basis of safety, efficacy, benefit, and timing vs risk and outcomes had to yet be developed, but major organizations became engaged in the issues. In 1982 the American Cancer Society (ACS) recommended that women at least 50 years old and younger women who were at risk receive mammograms “every year when feasible” (National Task Force on Breast Cancer Control, 1982). Mammography centers were established nationwide. The economic benefits of the centers to providers and producers introduced an economic variable and new conflicts of interest into women’s health care (Blakeslee, 1976). At that time, mammography was not high on the public’s or women’s agenda, in part because of a taboo about

openly discussing cancer in general and breast cancer specifically (Braun, 2003). However, when high-profile women, undoubtedly aided by a re-empowered feminist movement in the United States, spoke out about personal experiences with breast cancer (Braun, 2003; Corbett and Mori, 1999; Subak-Sharpe, 1976), the taboo was substantially diminished, and mass-media stories on breast cancer spiked in 1974 (Corbett and Mori, 1999). That spike in coverage was the largest recorded up to that point and portended increasing media attention to research. Compared with news coverage in the 1960s, news stories increased especially in the category of “screening and diagnosis.” Corbett and Mori (1999) found a lagged relationship of about 2 years between media coverage and increased breast-cancer incidence, which suggested an effect on screening behavior. They also observed a potential relationship between increased media coverage and discussion, increased publication of medical research articles, and increased federal funding of breast-cancer research.

Braun (2003) reviewed the history of advocacy by groups seeking to raise public awareness of breast-cancer issues. She described four chronologically overlapping phases, in all of which the mass media played an important role: an early phase, raising public awareness and understanding of the issue (“priming the market”); a second phase, “engaging consumers”; a third phase, “establishing political advocacy”; and finally “taking the advocacy mainstream.” In the l980s women’s health-advocacy groups emerged, such as the Susan Komen Race for the Cure, as did the establishment of guidelines that institutionalized the three-part approach to breast-cancer prevention: mammography, BSE, and BCE. By the middle 1990s, private and public advocacy efforts on behalf of research on breast cancer had dramatically increased funding not only through NIH but through the Department of Defense and the US Army.

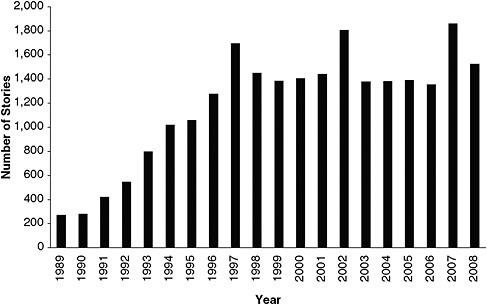

The increase in emphasis on breast cancer is illustrated in Figure 5-2. Specifically, the graph shows the growth of news coverage of mammography by major US news and wire-service outlets from 1989 through 2008 as reflected in the LexisNexis database. News coverage of mammography roughly doubled from 1989 to 1992 and again from 1992 to 1995. By 1997–1998, the high level of news coverage was continuous, and it was sustained through 2008. That appears to support Braun’s (2003) contention that breast-cancer advocacy activity has been strong and steady. Since the late 1990s, breast cancer has become a standard “repertoire” issue on the health agenda in government, science, women’s advocacy groups, and the communication media.

Mammography Standards

The successful implementation of the Mammography Quality Standards Act of 1992 (MQSA; Public Law 102-539) and the well-documented improvement in the quality of mammography services available to American women constitute a model for the dissemination and adoption of national standards for other services.

FIGURE 5-2 Number of news items on mammography in major US news and wire-service outlets listed in LexisNexis database, 1989–2008.

The MQSA evolved from a voluntary program created in 1987 by the American College of Radiology to address concerns about variations in mammography quality in the United States (Galkin et al., 1988; Suleiman et al., 1999). Accreditation became tied to evidence that facilities met standards for personnel, equipment, quality-assurance procedures, clinical images, phantom images, and dose. By 1991, one-fourth of the roughly 10,000 mammography units in the country had been accredited by American College of Radiology, and another one-fourth had sought accreditation but failed to meet the standards (McLelland et al., 1991). Following the voluntary program, state and federal legislation required facilities to meet quality standards, with all facilities requiring accreditation under the MQSA by October 1, 1994 (Destouet et al., 2005). Regulations have evolved in response both to new concerns about quality and to the development of new technologies, such as full-field digital mammography (IOM, 2005). There is now substantial research supporting the improvements in quality for patients since the uniform adoption of quality standards under the MQSA. This is an example of how research findings contribute both to the initial development of new screening and treatment services and to the evaluation of their implementation and of the value of mandatory standards in improving the quality of services (Destouet et al., 2005).

The Mass Media and Controversy

There has been continuing scientific study and changing interpretations of research surrounding the use of mammography as a regular screening tool for women’s breast health. The process has been complicated by the mass media’s interest in “news value,” which emphasizes novelty, conflict, and drama. At its best, media coverage generates public attention to and learning about important subjects and builds and sustains an issue on the public agenda. At its worst, it engenders confusion and perhaps fatalism that can lead to inaction (Dunwoody, 1999; Kitzinger and Reilly, 1997; Nelkin, 1995).

For example, in the early 1970s, ACS launched an initiative with NIH to test mammography’s detection ability. The partnership established the Breast Cancer Detection Demonstration Project (BCDDP), which engaged some 280,000 women volunteers 35–74 years old in receiving regular mammograms over 5 years (Finkel, 2005). It was not a clinical trial of effectiveness, but a feasibility demonstration involving 29 sites. It was a precursor to the health-care system’s potentially widespread investment in expensive technology. As Cunningham (1997) recounted, the project was criticized almost immediately in the media by some scientists and clinicians for its “risk, cost, effectiveness and purpose.” The director of the National Cancer Institute raised the question of radiation risks accruing from mammography, especially in women 35–50 years old, in a letter to the physicians at the BCDDP sites, stating his concerns and recommendations (Blakeslee, 1976; Cancer Institute Proposes Limits on Breast X-rays, 1976; Finkel, 2005). Although his recommendations had no official status, media coverage reduced the number of BCDDP volunteers who adhered fully to the demonstration protocol (Cunningham, 1997). This was never formally studied, but it may be that media coverage of the risk of contracting breast cancer from repeated mammography engendered enough uncertainty in the volunteers for many to choose not to continue (Dunwoody, 1999).

A 2001 research letter in the Lancet by two Cochrane Collaboration investigators who had conducted a systematic review of mammography sparked considerable controversy that appears to be linked to mass-media coverage (Steele et al., 2005). The investigators had re-examined the clinical trials that formed the basis of mammography guidelines, which were conducted in the 1980s and 1990s (Smith et al., 2004). In summarizing the collective results of those clinical trials, they said that “there is no reliable evidence that screening for breast cancer reduces mortality” (Olsen and Gotzsche, 2001). Steele and colleagues (2005) found that the media appeared to play a large role in the response to the study. Of the newspapers reviewed, only the Washington Post reported on the study’s finding when it was first published (Steele et al., 2005). However, 2 months later, the New York Times reported the findings in a front-page article; after that, there was a spike in coverage of the original findings and responses and statements issued by a number of government agencies. Media coverage of mammography spiked several times over the next year as some investigators reanalyzed the same

clinical-trial data and arrived at the opposite conclusion, health and medical organizations took out full-page newspaper advertisements pledging their continued support of mammography, and HHS issued new guidelines continuing to support mammography, which were underscored in a public hearing in the US Senate (HHS, 2002b).

Controversy emerged again in 2009 when an independent scientific panel of the US Preventive Services Task Force issued its findings. The task force had examined the evidence base again from the standpoint of risk of harm from vs benefits of mammography (Mandelblatt et al., 2009). It concluded that women under 50 years old who had no familial or personal history of breast cancer should not be screened routinely, but that “the decision to start regular, biennial screening mammography before the age of 50 years should be an individual one and take patient context into account, including the patient’s values regarding specific benefits and harms” (US Preventive Services Task Force, 2009), and that women 50–74 years old should be screened with mammography every 2 years rather than annually. The task force’s recommendations were based on its evaluation of conclusions about risk and harm based on how the task force members ranked the quality of available evidence. It suggested—on the basis of the research as it existed, with all its flaws and challenges—that the accepted mammography guidelines interpreted benefits too liberally and harm too conservatively. It used multiple indicators of harm from false-positive results, including psychologic harm from unnecessary anxiety and physical-health risks from additional tests. That is more complicated and harder to understand than a simple balance of lives saved due to one or another treatment and, in many cases, the message that was conveyed was that women under 50 should not routinely be screened for breast cancer.

Media coverage spiked rapidly (Woolf, 2010). One reason for the interest was that professional experts, key institutions, advocacy groups, and the government might have different perspectives, and the report challenged established guidelines developed by those stakeholders. Complicating matters was that its release occurred at the height of the US Senate debate regarding national health-care reform. Opponents of reform efforts seized on the report as evidence that the US government was intent on a policy of “health-care rationing” that would endanger women’s health (Woolf, 2010). Individual women testified that if the proposed recommendations had been followed by their health-care providers, they would probably not have survived their breast cancers. Such anecdotes and arguments were easier to convey in brief sound-bites than the more complicated balance of harm vs benefit and the more abstract concept of population-attributable risk. The panel appeared to have been surprised by the intense controversy and did not have an immediate strategy for dealing with the reactions to its report.

The issues illustrated by the controversies surrounding mammography will continue to occur in this and other fields. Science evolves and different groups will have different guidelines and recommendations depending on how they weigh the scientific evidence.

Lessons Learned

The case of mammography illustrates the interaction of the forces and factors of science, politics, economics, and culture that combine with mass-media communication to shape and reshape the research agenda for women’s health and the health services that they receive. The process frames the meaning of women’s health itself and the interpretation and limits of scientific data. The meaning and interpretation of scientific results is often variable and contentious, especially as findings are translated into clinical recommendations and strategies for improving women’s health. The dynamics of the mammography issue offer a case in point about the struggle of conveying in the media the meaning and interpretation of scientific findings given the sometimes conflicting opinions within the scientific community about the findings and how best to effectively convey the messages. Although the portrayal of conflict can increase the salience of an issue so as to gain the public’s attention, it can also foster contentiousness among policy makers, scientists, and others. Such conflict runs the risk of discouraging and confusing women potentially to the point of fatalism about the causes and prevention of breast cancer. That impact is greater on those of lower SES, who tend to have poorer health outcomes overall.

CONCLUSIONS

-

Barriers delay or preclude the translation of findings of women’s health research into practice. Those barriers range from fragmentation of health-care delivery and health-care policies, and reimbursement to the complexity of science and research, challenges in communicating understandable and actionable messages, and consumer confusion and apprehension. Few studies of how to increase the speed or extent of translation of findings related to women’s health into clinical practice have been conducted. Clinical-practice guidelines, mandatory standards, reimbursement practices, laws (including public-health laws), and health-professions school curricula and continuing education are some methods of translation that have been used and warrant evaluation for translating research findings on women.

-

Women are, in general, a receptive audience for medical messages and information. Many messages, however, are confusing because of conflicting results and uncertainty in data. Improved strategies for communicating research results to the public are needed.

RECOMMENDATIONS

-

Research should be conducted on the best ways to translate research findings on women’s health into clinical practice and public-health policies rapidly. Research findings should be incorporated at the practitioner level and at the overall public-health systems level through, for example, the use of targeted

-

education programs for practitioners and the development of guidelines. Research on what messages women find confusing and how those messages could be delivered in a more effective manner is needed. As those programs and guidelines are developed and implemented, they should be evaluated to ensure effectiveness.

-

HHS should appoint a task force to develop an evidence-based strategy to communicate and market health messages to women that are based on objective research results. In addition to content experts in relevant departments and agencies, the task force should include mass-media and targeted-messaging and marketing experts. The goals of the strategy should include effective communication to the diverse audience of women; increasing awareness of women’s health issues and treatments, including prevention and intervention strategies; and decreasing confusion in light of complex and sometimes conflicting health messages. Strategies to explore might include

-

requiring a plan for communication and dissemination of findings in government-funded studies to the public, providers, and policy makers, similar to the requirement to have a data and safety monitoring board in those studies;

-

establishing a national media advisory panel with experts in women’s health, which would be readily available to provide context to reporters, scientists, clinicians, and policy makers at the time of release of important or potentially complex new research reports. (One goal of the panel could be to explain discrepancies and uncertainties in research findings); and

-

creation by the HHS OWH of a program dedicated to translation of findings of women’s health research into practice.

-

REFERENCES

Allsop, J., K. Jones, and R. Baggott. 2004. Health consumer groups in the UK: A new social movement? Sociology of Health & Illness 26(6):737–756.

Arora, N. K., B. W. Hesse, B. K. Rimer, K. Viswanath, M. L. Clayman, and R. T. Croyle. 2008. Frustrated and confused: The American public rates its cancer-related information-seeking experiences. Journal of General Internal Medicine 23(3):223–228.

Bansal, A. T., and M. R. Barnes. 2008. Genomics in drug discovery: The best things come to those who wait. Current Opinion in Drug Discovery & Development 11(3):303–310.

Barber, C. A., K. Margolis, R. V. Luepker, and D. K. Arnett. 2004. The impact of the Women’s Health Initiative on discontinuation of postmenopausal hormone therapy: The Minnesota Heart Survey (2000–2002). Journal of Women’s Health 13(9):975–984.

Bean-Mayberry, B., E. M. Yano, N. Bayliss, J. Navratil, C. S. Weisman, and S. H. Scholle. 2007a. Federally funded comprehensive women’s health centers: Leading innovation in women’s healthcare delivery. Journal of Women’s Health 16(9):1281–1290.

Bean-Mayberry, B. A., E. M. Yano, C. D. Caffrey, L. Altman, and D. L. Washington. 2007b. Organizational characteristics associated with the availability of women’s health clinics for primary care in the veterans health administration. Military Medicine 172(8):824–828.

Belkora, J. K., M. K. Loth, S. Volz, and H. S. Rugo. 2009. Implementing decision and communication aids to facilitate patient-centered care in breast cancer: A case study. Patient Education and Counseling 77(3):360–368.

Berger, J. S., M. J. Krantz, J. M. Kittelson, and W. R. Hiatt. 2009. Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with peripheral artery disease: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Journal of the American Medical Association 301(18):1909–1919.

Bero, L. A., R. Grilli, J. M. Grimshaw, E. Harvey, A. D. Oxman, and M. A. Thomson. 1998. Closing the gap between research and practice: An overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Review Group. British Medical Journal 317(7156):465–468.

Berwick, D. M. 2003. Disseminating innovations in health care. Journal of the American Medical Assocation 289(15):1969–1975.

Bird, C. E., A. M. Fremont, A. S. Bierman, S. Wickstrom, M. Shah, T. Rector, T. Horstman, and J. J. Escarce. 2007. Does quality of care for cardiovascular disease and diabetes differ by gender for enrollees in managed care plans? Women’s Health Issues 17(3):131–138.

Blakeslee, A. 1976. Women shouldn’t fear breast x-rays: Doctor. Associated press wire story. St. Petersburg Times, September 5, 15A.

Bluming, A. Z., and C. Tavris. 2009. Hormone replacement therapy: Real concerns and false alarms. Cancer Journal 15(2):93–104.

Braddock, C. H., S. D. Fihn, W. Levinson, A. R. Jonsen, and R. A. Pearlman. 1997. How doctors and patients discuss routine clinical decisions: Informed decision making in the outpatient setting. Journal of General Internal Medicine 12(6):339–345.

Braun, S. 2003. The history of breast cancer advocacy. Breast Journal 9:S101–S103.

Breslau, E. S., W. W. Davis, L. Doner, E. J. Eisner, N. R. Goodman, H. I. Meissner, B. K. Rimer, and J. E. Rossouw. 2003. The hormone therapy dilemma: Women respond. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association 58(1):33–43.

Burton, B., and A. Rowell. 2003. Unhealthy spin. British Medical Journal 326(7400):1205–1207.

Bush, T. M., A. E. Bonomi, L. Nekhlyudov, E. J. Ludman, S. D. Reed, M. T. Connelly, L. C. Grothaus, A. Z. LaCroix, and K. M. Newton. 2007. How the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) influenced physicians’ practice and attitudes. Journal of General Internal Medicine 22(9):1311–1316.

California Health Interview Survey. 2010. Ask CHIS: 2007 California health survey. http://www.chis. ucla.edu/main/DQ3/output.asp?_rn=0.2069513 (accessed August 16, 2010).

Cancer Institute Proposes Limits on Breast X-Rays. 1976. New York Times (1923–Current file), 12. Charo, R. A. 2007. Politics, parents, and prophylaxis—mandating HPV vaccination in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 356(19):1905–1908.

Chauhan, M. S., K. K. Ho, D. S. Baim, R. E. Kuntz, and D. E. Cutlip. 2005. Effect of gender on in-hospital and one-year outcomes after contemporary coronary artery stenting. American Journal of Cardiology 95(1):101–104.

Chlebowski, R. T., S. L. Hendrix, R. D. Langer, M. L. Stefanick, M. Gass, D. Lane, R. J. Rodabough, M. A. Gilligan, M. G. Cyr, C. A. Thomson, J. Khandekar, H. Petrovitch, and A. McTiernan. 2003. Influence of estrogen plus progestin on breast cancer and mammography in healthy post-menopausal women: The Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 289(24):3243–3253.

Chlebowski, R. T., L. H. Kuller, R. L. Prentice, M. L. Stefanick, J. E. Manson, M. Gass, A. K. Aragaki, J. K. Ockene, D. S. Lane, G. E. Sarto, A. Rajkovic, R. Schenken, S. L. Hendrix, P. M. Ravdin, T. E. Rohan, S. Yasmeen, G. Anderson, and the WHI Investigators. 2009. Breast cancer after use of estrogen plus progestin in postmenopausal women. New England Journal of Medicine 360(6):573–587.

Christian, A. H., W. Rosamond, A. R. White, and L. Mosca. 2007. Nine-year trends and racial and ethnic disparities in women’s awareness of heart disease and stroke: An American Heart Association national study. Journal of Women’s Health (2002) 16(1):68–81.

Corbett, J. B., and M. Mori. 1999. Medicine, media, and celebrities: News coverage of breast cancer, 1960–1995. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 76(2):229–249.

Cunningham, M. P. 1997. The breast cancer detection demonstration project 25 years later. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 47(3):131–133.

Cuzick, J., T. Powles, U. Veronesi, J. Forbes, R. Edwards, S. Ashley, and P. Boyle. 2003. Overview of the main outcomes in breast-cancer prevention trials. Lancet 361(9354):296–300.

Destouet, J. M., L. W. Bassett, M. J. Yaffe, P. F. Butler, and P. A. Wilcox. 2005. The ACR’s mammography accreditation program: Ten years of experience since MQSA. Journal of the American College of Radiology 2(7):585–594.

Donohue, G. A., P. J. Tichenor, and C. N. Olien. 1975. Mass media and the knowledge gap: A hypothesis reconsidered. Communication Research 2(1):3–23.

Dunwoody, S. 1999. Scientists, journalists, and the meaning of uncertainty. In Communicating Uncertainty: Media Coverage of New and Controversial Science, edited by S. M. Friedman, S. Dunwoody and C. L. Rogers. Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates. Pp. 59–79.

Estabrook, L. S., E. G. Witt, and H. Rainie. 2007. Information Searches That Solve Problems: How People Use the Internet, Libraries, and Government Agencies When They Need Help. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project.

Fallows, D. 2005. How Women and Men Use the Internet: Women Are Catching Up to Men in Most Measures of Online Life; Men Like the Internet for the Experiences It Offers, While Women Like It for the Human Connections It Promotes. http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2005/PIP_Women_and_Men_online.pdf.pdf (accessed December 8, 2009).

Farquhar, C., R. Basser, S. Hetrick, A. Lethaby, and J. Marjoribanks. 2003. High dose chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow or stem cell transplantation versus conventional chemotherapy for women with metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1: CD003142.

FDA (US Food and Drug Administration). 1998. The oncologist news bulletin. Oncologist 3(6): 452–454.

Finkel, M. L. 2005. Understanding the Mammography Controversy: Science, Politics, and Breast Cancer Screening. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Fisher, B., J. P. Costantino, D. L. Wickerham, C. K. Redmond, M. Kavanah, W. M. Cronin, V. Vogel, A. Robidoux, N. Dimitrov, J. Atkins, M. Daly, S. Wieand, E. Tan-Chiu, L. Ford, and N. Wolmark. 1998. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: Report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 90(18):1371–1388.

Fogel, J., S. M. Albert, F. Schnabel, B. A. Ditkoff, and A. I. Neugut. 2002. Use of the internet by women with breast cancer. Journal of Medical Internet Research 4(2):E9.

Foster, R. S. J., and M. C. Costanza. 1984. Breast self-examination practices and breast cancer survival. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 39(6):404.

Fox, S. 2006. Online Health Search 2006. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project.

Franklin, L., J. Belkora, S. O’Donnell, D. Elsbree, J. Hardin, B. Ingle, and N. Johnson. 2009. Consultation support for rural women with breast cancer: Results of a community-based participatory research study. Patient Education and Counseling 80(1):80–87.

French, L. M., M. A. Smith, J. S. Holtrop, and M. Holmes-Rovner. 2006. Hormone therapy after the Women’s Health Initiative: A qualitative study. BMC Family Practice 7:61.

Galkin, B. M., S. A. Feig, and H. D. Muir. 1988. The technical quality of mammography in centers participating in a regional breast cancer awareness program. Radiographics 8(1):133–145.

Gandy, O. H. 1982. Beyond Agenda Setting: Information Subsidies and Public Policy, Communication and Information Science; Variation: Communication and Information Science. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Garbe, E., and S. Suissa. 2004. Issues to debate on the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Study: Hormone replacement therapy and acute coronary outcomes: Methodological issues between randomized and observational studies. Human Reproduction 19(1):8–13.

Gold, R. H. 1992. The evolution of mammography. Radiologic Clinics of North America 30(1): 1–19.

Goodman, R. M., M. R. Seaver, S. Yoo, S. Dibble, R. Shada, B. Sherman, F. Urmston, N. Milliken, and K. M. Freund. 2002. A qualitative evaluation of the national centers of excellence in women’s health program. Womens Health Issues 12(6):291–308.

Gorringe, R., M. M. Lee, and A. Voda. 1978. The mammography controversy: A case for breast self-examination. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing 7(4):7–12.

Grady, D., L. Chaput, and M. Kristof. 2003. Results of systematic review of research on diagnosis and treatment of coronary heart disease in women. In Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. No. 80. (Prepared by the University of California, San Francisco—Stanford Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No 290-97-0013.) AHRQ Publication No. 03-0035. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Green, B. B., and S. H. Taplin. 2003. Breast cancer screening controversies. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice 16(3):233–241.

Haas, J., B. Geller, D. L. Miglioretti, D. S. Buist, D. E. Nelson, K. Kerlikowske, P. A. Carney, E. S. Breslau, S. Dash, M. K. Canales, and R. Ballard-Barbash. 2006. Changes in newspaper coverage about hormone therapy with the release of new medical evidence. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21(4):304–309.

Haas, J., D. Miglioretti, B. Geller, D. Buist, D. Nelson, K. Kerlikowske, P. Carney, S. Dash, E. Breslau, and R. Ballard-Barbash. 2007. Average household exposure to newspaper coverage about the harmful effects of hormone therapy and population-based declines in hormone therapy use. Journal of General Internal Medicine 22:68–73.

Harman, S. M., F. Naftolin, E. A. Brinton, and D. R. Judelson. 2005. Is the estrogen controversy over? Deconstructing the Women’s Health Initiative Study: A critical evaluation of the evidence. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1052:43–56.

Harris Interactive. 2008a. Four Out of Five Adults Now Use the Internet. http://www.harrisinteractive.com/harris_poll/index.asp?PID973 (accessed April 15, 2009).

———. 2008b. Number of “Cyberchondriacs”—Adults Going Online for Health Information—Has Plateaued or Declined. http://www.harrisinteractive.com/harris_poll/index.asp?PID937 (accessed April 25, 2009).

Hausauer, A., T. Keegan, E. Chang, S. Glaser, H. Howe, and C. Clarke. 2009. Recent trends in breast cancer incidence in US white women by county-level urban/rural and poverty status. BMC Medicine 7(1):31.

Heiss, G., R. Wallace, G. Anderson, A. Aragaki, S. Beresford, R. Brzyski, R. Chlebowski, M. Gass, A. LaCroix, J. Manson, R. Prentice, J. Rossouw, and M. L. Stefanick. 2008. Health risks and benefits 3 years after stopping randomized treatment with estrogen and progestin. Journal of the American Medical Association 299(9):1036–1045.

Henson, R. M., S. W. Wyatt, and N. C. Lee. 1996. The National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program: A comprehensive public health response to two major health issues for women. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 2(2):36–47.

Herbst, A. L., and D. Anderson. 1990. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix secondary to intrauterine exposure to diethylstilbestrol. Seminars in Surgical Oncology 6(6):343–346.

Herxheimer, A. 2003. Relationships between the pharmaceutical industry and patients’ organisations. British Medical Journal 326(7400):1208–1210.

HHS (US Department of Health and Human Services). 2002a. NHLBI Stops Trial of Estrogen Plus Progestin Due to Increased Breast Cancer Risk, Lack of Overall Benefit. Washington, DC.

———. 2002b. News Release: NCI Statement on Mammography Screening, Edited by National Cancer Institute. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services.

———. 2004. NHLBI Advisory for Physicians on the WHI Trial of Conjugated Equine Estrogens Versus Placebo. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/whi/e-a_advisory.htm (accessed April 12, 2010).

———. 2010. About the Heart Truth Campaign. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/educational/hearttruth/about/index.htm (accessed March 17, 2010).

Hilgartner, S., and C. L. Bosk. 1988. The rise and fall of social problems: A public arenas model. American Journal of Sociology 94(1):53–78.

Hoffmann, M., M. Hammar, K. I. Kjellgren, L. Lindh-Astrand, and J. Brynhildsen. 2005. Changes in women’s attitudes towards and use of hormone therapy after HERS and WHI. Maturitas 52(1):11–17.