3

Research on Conditions with Particular Relevance to Women

This chapter discusses women’s health research of the last 2 decades according to conditions.1 The committee limits its discussion according to its characterization of women’s health in Chapter 1—conditions that are specific to women; that are more common or serious in women; that have distinct causes, manifestations, outcomes, or treatments in women; or that have high morbidity or mortality in women. Appendix B summarizes the incidence, prevalence, and mortality data and trends that, in part, guided committee selections.

Given the impossibility of presenting all research on women’s health, the committee first discusses examples of successful research that contributed to progress in women’s health. The committee assessed progress on the basis of decreases in incidence or mortality or on the basis of scientific innovations that led to major transformations in approaching a condition. The committee then discusses conditions on which some progress has been made and those on which little progress has been made and about which heightened awareness and further research are needed. Although aware of comorbidities and cross-cutting issues, the committee organized the data for this chapter by condition to reflect of predominant models of research funding and publications.

The committee is aware that the conditions do not include all health conditions that are important to women; a number of conditions that affect many women’s quality of life—including arthritis, chronic fatigue syndrome, chronic pain, colorectal cancer, eating disorders, fibromyalgia, incontinence, irritable bowel syndrome, many pregnancy-related issues, melanoma, memory and cognitive changes associated with perimenopause, mental illness other than depression,

migraines, sexual dysfunction, stress-related disorders, thyroid disease, and type 2 diabetes—are not discussed here. Because of the volume of literature available, the committee could not discuss the research on all health conditions important to women and on some conditions there was little research to discuss. Absence of discussion does not indicate that the committee thought it unimportant. The committee highlighted conditions to provide examples of successes and examples of less progress on which overarching conclusions and recommendations can be based.

The diseases on which there has been substantial progress are breast cancer, cardiovascular disease, and cervical cancer. Conditions on which there has been some progress are depression, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), and osteoporosis. The committee discusses research on other conditions—unintended pregnancy,2 maternal mortality and morbidity, autoimmune diseases, alcohol and drug addiction, lung cancer, gynecologic cancers other than cervical cancer, non-malignant gynecological disorders, and dementia of the Alzheimer type (Alzheimer’s disease)—on which little progress has been made.

Each condition is discussed with regard to a brief evaluation of advances in research; its relevance to women’s health in terms of current incidence, prevalence, and mortality rates and trends therein; disparities in current incidence, prevalence, and mortality rates and trends therein among groups of women (see Box 3-1 for explanation of data on disparities); advances in research, particularly in relation to women’s health encompassing research on the understanding of the biology, prevention,3 and diagnosis of, screening, and treatment for it; research gaps; and lessons learned from the research and extent of progress. When discussing treatments, the committee focuses on conventional treatments and does not discuss complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in detail. As discussed in a previous Institute of Medicine (IOM) report (2005), women are more likely than men to seek CAM therapies and, therefore, those therapies are important to consider when looking at women’s health, from the perspective of potential therapies as well as their potential toxicities and interactions with other medications. The reader is referred to the previous IOM report for further details on CAM research (IOM, 2005).

It is important to note that trends in incidence need to be interpreted in the context of changes in diagnostic criteria and technologies, which can result in the appearance of an increased incidence of a condition (see Box 3-2). This chapter addresses questions 2, 3, and 4 from Box 1-4, whether women’s health research is

|

2 |

The committee considered whether to discuss unintended pregnancy as a health outcome or a determinant of health. It decided to discuss it as an outcome, along with maternal mortality and morbidity, and discuss the determinants that increase the rate of unintended pregnancies in Chapter 2. |

|

3 |

Non-biological determinants of health are mentioned only briefly in this chapter. Details of research on them are discussed in Chapter 2. |

|

BOX 3-1 Data on Disparities Incidence, prevalence, and trend data across races and ethnicities are presented as available. For some conditions for which there is active surveillance, such as cancer, data are routinely collected and presented by race or ethnicity. For other conditions, data are available from the published literature. |

|

BOX 3-2 Interpretation of Changes in Incidence In looking at changes in incidence, it is important to consider whether an increase or a decrease in a rate is due to a real trend in occurrence or to a change in diagnostic criteria, sensitivity of diagnostic tests, screening programs, or another external factor that changes the likelihood of finding a case and might make it appear that incidence is changing (Devesa et al., 1984). For example, some increases seen in breast-cancer incidence have been attributed to more intensive screening programs increasing the ascertainment of cases and not an increase in the secular trend (Seigneurin et al., 2008). |

focused on the most appropriate and relevant conditions and end points, whether it is studying the most relevant groups of women, and whether the most appropriate research methods are being used.

CONDITIONS ON WHICH RESEARCH HAS CONTRIBUTED TO MAJOR PROGRESS

Breast Cancer

The committee considered a large and diverse body of scientific research on breast cancer to have contributed to major progress in understanding the basic biology of breast cancer and the identification of specific risk factors, which led to prevention efforts; in improvements in the detection and treatment of breast cancer; and ultimately in a decrease in mortality rates.

Incidence, Prevalence, and Mortality in Women

During the last 2 decades, there has been heavy investment in breast-cancer research owing in part to the lobbying efforts of breast-cancer survivors and

advocates (IOM, 2004a). One example is the authorization by Congress of a new funding mechanism for breast-cancer research through the Department of Defense, initially focused on pursuing interservice research on breast-cancer screening and diagnosis for military women and dependents of military men (IOM, 2004a). Increased funding was also made available from the National Cancer Institute, other government agencies (such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ]), and individual statewide programs (such as the California Breast Cancer Research Program, funded with tobacco-tax funds). In parallel, the private philanthropic community—such as the Susan G. Komen Foundation, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and Avon—raised awareness and money for research to improve treatment and quality of life of the growing number of breast-cancer survivors.

After remaining relatively steady from 1975 to 1990, the overall invasive– breast-cancer mortality in women in the United States began a steady fall in 1990 and continued to drop each year between 1998 and 2007 (NCI, 2010a). The age-adjusted mortality4 from invasive breast cancer dropped from 33.1 per 100,000 women in 1990 to 22.8 per 100,000 women in 2007 (NCI, 2010a). A consortium of investigators using 7 statistical models indicated that the portion of the reduction in mortality attributable to improved or increased screening varied from 28 to 65% (median, 46%), and the remainder was attributed to improved adjuvant therapies (Berry et al., 2005). Breast cancer, however, is still the second-leading cause of cancer deaths in women in the United States (ACS, 2009a; CDC, 2010).5

Despite many gains from research and regardless of the recent drop in mortality, the incidence of breast cancer in women is higher now than in 1975, and breast cancer is the most common non-skin cancer in women in the United States, estimated to account for about 28% of new cancer cases in 2010 (Jemal et al., 2010). The age-adjusted incidence of breast cancer was as high as 141.2 per 100,000 women in 1998 and 1999, and decreased to 124.7 per 100,000 women in 2007, up from about 100–105 per 100,000 women in 1975–1980 (NCI, 2010b). Much of the increase between 1980 and 1998 occurred during the 1980s and reflected increased detection of localized tumors through increased mammographic screening (Garfinkel et al., 1994; Miller et al., 1991; White et al., 1990). During those years, the incidence increased in every 4-year age group above 45 years. From 1999 to 2003, the age-specific incidence of breast cancer decreased in every age group over 45 years (Jemal et al., 2007). Jemal and colleagues (2007) con-

|

4 |

Data are from US Mortality Files, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rates are age-adjusted to the 2000 US Standardized Population (19 age groups—Census P25-1130). |

|

5 |

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in women; cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death overall in women (see Appendix B for data). |

cluded that part of the decrease is “consistent with saturation in screening mammography.” The large decreases in invasive estrogen-positive breast cancers seen after July 2002 have been attributed to the identification, through the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), of an increased risk of breast cancer associated with the use of menopausal hormone therapy and a precipitous decline in the number of hormone prescriptions filled after the rapid dissemination of that finding to women who were on hormone therapy (Chlebowski et al., 2009; Hausauer et al., 2009; Ravdin et al., 2007). Sharp decreases in breast cancer from 2002 to 2003 were seen in estrogen-positive tumors in women 50–69 years old (Jemal et al., 2007) and, in a study of white women, were largest in urban counties and counties that had low poverty rates (Hausauer et al., 2007).

Disparities Among Groups

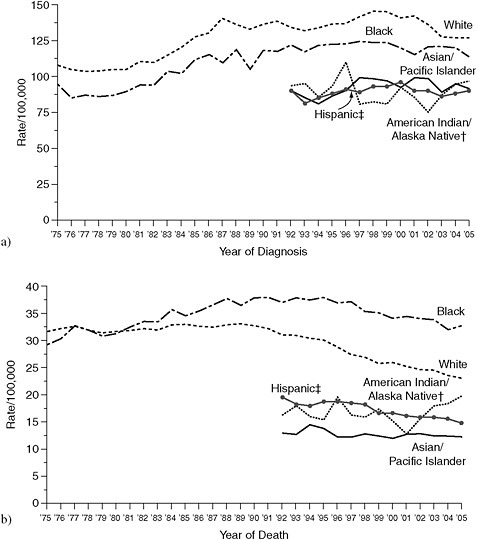

Large disparities in breast-cancer incidence and mortality exist among different demographic groups (see Figure 3-1). Breast cancer is one of the few diseases whose incidence is higher in white women than in other ethnic groups; however, black women have higher mortality. Breast-cancer mortality increased in black women from 1975 to 1995—a period when breast cancer mortality in white women decreased (NCI, 2010b). Mortality in black women leveled off and began to decrease in 1995 (see Figure 3-1), but in 2005 mortality in black women (32.8 per 100,000) was still higher than in white women (23.3 per 100,000). The disparity is particularly high in black women under 50 years old (Baquet et al., 2008; DeSantis et al., 2008; Ghafoor et al., 2003; Grann et al., 2006). Both incidence and mortality are lower in Hispanic, Asian and Pacific Islander, and American Indian and Alaskan Native women than in white or black women (Ghafoor et al., 2003). Recently, Kinsey and colleagues (2008) examined breast-cancer mortality in black and white women in 1993–2001 as related to 4 levels of education. Mortality decreased by 1.4% in white women who had less than 12 years of education and by 4.3% in white women who had more than 16 years of education. In black women, a decrease (3.8%) was seen only in women who had more than 16 years of education; this shows an association of both race and education with breast-cancer mortality. American Indian and Alaskan Native women are also more likely to receive a diagnosis of late-stage disease than non-Hispanic white women (Wingo et al., 2008). Research has documented that Ashkenazi Jewish women have a genetic susceptibility to breast cancer (Rubinstein, 2004).

The high case-fatality rate from breast cancer in black women had been hypothesized as being due to differences in biologic factors and in access to timely screening and care (Ademuyiwa and Olopade, 2003; Shavers and Brown, 2002). The Carolina Breast Cancer Study showed that basal-like breast tumors were more prevalent among premenopausal African American women than among postmenopausal African American and non–African American women. That suggests a biologic cause of the excess mortality in young black women and leads

FIGURE 3-1 Annual breast cancer (a) incidence and (b) mortality in the United States by race or ethnicity. Incidence source: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, National Cancer Institute (NCI)—1975–1991, SEER 9; 1992–2005, SEER 13. Mortality source: US Mortality Files, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rates age-adjusted to the 2000 US standard population (19 age groups—Census P25-1130).

†Rates for American Indians and Alaska Natives based on Contract Health Service Delivery Area counties.

‡Hispanics are not mutually exclusive from whites, blacks, Asians and Pacific Islanders, and American Indians and Alaskan Natives. Incidence data on Hispanics are based on the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries Hispanic Identification Algorithm and exclude cases from the Alaska Native Registry. Mortality data on Hispanics do not include cases from Connecticut, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Vermont.

SOURCE: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/statistics/race.htm (accessed May 3, 2010).

to the option of more aggressive therapies for this patient cohort (see below for discussion of treatment options) (Carey et al., 2006). Issues related to access to screening and care are discussed in Chapter 2; more details on the biology of breast cancer are discussed below.

Research Advances in Knowledge of Biology

Epidemiologic research has identified a variety of factors that are associated with changes in reproductive hormones that are also associated with breast cancer, such as age at first full-term pregnancy, number of full-term pregnancies, breastfeeding, and age at menarche and menopause. Through many types of studies, research has uncovered the role of estrogen in breast-cancer pathogenesis. It is known that estrogen binds to nuclear estrogen receptor α and, with the addition of cofactors, stimulates cell proliferation (Hall and McDonnell, 2005), and it is thus a risk factor for breast cancer. During the last decade, a second estrogen receptor, estrogen receptor β was identified (Kuiper et al., 1996; Mosselman et al., 1996). It is thought that estrogen mediates estrogen–receptor–signaling cross-talk with insulin-like growth-factor receptors to mediate breast-cancer pathogenesis (Clemons and Goss, 2001; Lee et al., 1999).

A family history of breast cancer is also a risk factor for breast cancer, and genetic research has provided an understanding of many of the mechanisms that underlie breast cancer (Hua et al., 2008; Olopade et al., 2008). Mutations in two tumor-suppressor genes—BRCA1 and BRCA2—are associated with breast cancer (Antoniou et al., 2008; Claus et al., 1998; Collins et al., 1995; Easton et al., 1993; Hall et al., 1990; Schubert et al., 1997) and responsible for 5–10% of breast cancers (ACS, 2010a). The germ-line BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are highly penetrant and greatly increase a person’s risk of breast cancer (Easton et al., 1993; Rowell et al., 1994). BRCA1 breast cancers are typically poorly differentiated, high-grade, infiltrating ductal carcinomas and are usually estrogen-receptor (ER)–negative, progesterone-receptor–negative, and Human Epidermal Receptor type 2 (HER2)/neu–negative (Bordeleau et al., 2010). BRCA2 breast cancer is characterized by early age of onset, bilaterality, and association with a risk of ovarian cancer (Frank et al., 1998; Krainer et al., 1997). Later research has identified other gene mutations that are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, including TP53 (the human gene that encodes P53), PTEN, CASP8, FGFR2, MAP3K1, and LSP1 (see Garcia-Closas and Chanock, 2008, for review). Most of those mutations are low-penetrance variants, and much of the genetic component of breast cancer is not accounted for by known gene mutations.

The understanding of the cellular biology of breast cancer has improved over the past 2 decades, contributing to the development of a number of therapies directed toward interrupting pathways in breast-cancer cells for the prevention and treatment of breast cancer. In particular, the roles of a number of receptors in breast-cancer cells have been identified. Approximately two-thirds of breast cancers express ER. There are two types of estrogen receptors (α and β), but at

present only ERα has any known clinical significance. Withdrawal of estrogen (by oophorectomy) was shown to be an effective treatment for breast cancer in the 1890s (Beatson, 1896). Subsequently developed therapies directed toward interrupting the estrogen/ER pathway have been prime tools in treatment and prevention of breast cancer (see below).

HER2, also know as erbB2 and c-neu, is a member of the epidermal growth factor receptor family. Approximately 20–30% of breast cancers have amplified HER2 gene and/or over-express the protein (Cooke et al., 2001; Press et al., 1993; Slamon et al., 1987, 1989; Wolff et al., 2007; Zell et al., 2009). HER2 has been shown to be associated with poorer prognosis in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer, but it is also the target of specifically designed therapeutics directed toward it.

In addition to the ER and HER2 systems, several other important biologic pathways have been identified that have been shown or might serve as therapeutic targets in breast cancer. These include neo-angiogenesis, as mediated by the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). This molecule is the target for bevacizumab, which has activity in the metastatic setting (Miller et al., 2007). Other investigational pathways include, but are not limited to, the insulin-like growth factors (IGFRs), mammalian target of rapamycin (M-TOR), AKT, PI3K, and MEK.

Research Advances in Prevention

Many factors and exposures that are associated with both increasing and decreasing risk of breast cancer can be addressed to help to decrease the incidence of breast cancer, including those presented in Box 3-3.

A major research finding from the WHI was the confirmation of an increased risk of breast cancer associated with the use of conjugated equine estrogen plus progestin (Prempro™) but not with estrogen alone (Premarin™) (Chlebwski et al., 2003; Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators, 2002). The dissemination of that finding resulted in a rapid decrease in the use of menopausal hormone therapy (Haas et al., 2004; Hersh et al., 2004) and a later decrease in breast cancer incidence (Krieger et al., 2010; Ravdin et al., 2007). That decline, however, was not seen equally across all socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic groups (Krieger et al., 2010).

Alcohol, even in moderate amounts, can increase the risk of breast cancer6 (see Suzuki et al., 2008, for meta-analysis), as can poor diet (see Norman et al., 2007, for review), and more specifically, obesity (Brown and Simpson, 2010; Schapira et al., 1994; Vainio and Bianchini, 2002a). Evidence suggests that the common mechanism whereby alcohol and obesity increase the risk of breast can-

|

6 |

Both the adverse and beneficial effects of alcohol consumption are discussed further in Chapter 2. |

|

BOX 3-3 Factors Associated with Breast Cancer Factors Associated with Increased Risk of Breast Cancer Hormone therapy Ionizing radiation Obesity Alcohol Genetic factors Factors Associated with Decreased Risk of Breast Cancer Exercise Early pregnancy Breastfeeding Treatments Associated with Risk of Breast Cancer Selective estrogen-receptor modulators Aromatase inhibitors or inactivators Prophylactic mastectomy SOURCE: National Cancer Institute. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/prevention/breast/HealthProfessional (accessed August 3, 2010). |

cer is an increase in estrogen, which stimulates the proliferation of breast tissue (Brown and Simpson, 2010; Cleary et al., 2010; Ginsburg et al., 1996). The relationship between smoking and breast cancer is not clear. As reviewed by Coyle (2009), although data on deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) adducts provide biological plausibility for an association between smoking and breast cancer, epidemiology studies have either shown no association or an inverse association. There is some evidence, however, that smoking during a first pregnancy (Innes and Byers, 2001) and secondhand-smoke exposure are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (Cal EPA, 2005). The research on relevant behavioral factors is discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.

Exposure to ionizing radiation can increase the risk of breast cancer, especially if it occurs before the age of 20 years (Ronckers et al., 2005). Most studies that showed an increased risk of breast cancer in association with exposure to ionizing radiation looked at radiation levels higher than occur in mammography (Nelson et al., 2009a).

However, exercise, early pregnancy, and number of pregnancies predict a decrease in breast cancer, again with some evidence of a role of estrogen in the altered risk (Bernstein, 2008; Britt et al., 2007; Monninkhof et al., 2007; Pines, 2009).

Preventive measures apart from modifying risk factors have been developed for people at high risk for breast cancer. Recommendations for preventive options for breast cancer depend on a person’s risk (Guarneri and Conte, 2009; Sparano

et al., 2009). In very high-risk people—those who have a germ-line mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2 with lobular carcinoma in situ and a strong family history of breast cancer—prophylactic mastectomy is an option to consider to reduce the risk of breast cancer (Bermejo-Pérez et al., 2007; Kaas et al., 2010; Nusbaum and Isaacs, 2007; Zakaria and Degnim, 2007), as is prophylactic oophorectomy (Metcalfe, 2009; Rebbeck et al., 2009). For people who have a high risk because of family history, chemoprevention is available. During the last 2 decades, 2 large sequential breast-cancer-prevention trials of healthy women at high risk for breast cancer demonstrated that treatment with tamoxifen (a selective estrogen receptor modulator) for 5 years could reduce the risk of invasive breast cancer by at least 50% (Fisher et al., 1998; Veronesi et al., 2007). Tamoxifen also reduced the risk of recurrent breast cancer after treatment in both younger and older women (Cuzick et al., 2003; Lewis, 2007; Schrag et al., 2000). In a study of postmenopausal women with a mean age of 58.5 years, tamoxifen and raloxifene (a selective estrogen receptor modulator approved for prevention of osteoporosis) had similar efficacy in reducing the risk of invasive breast cancer (Vogel et al., 2006). As a result of that research, older women at high risk for breast cancer now have two US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved medications that reduce the risk of breast cancer and of osteoporosis. Side effects, however, contribute to low acceptance and use of tamoxifen (Fallowfield, 2005). In addition, identifying at-risk people can pose a problem.

Research Advances in Diagnosis

A number of diagnostic and screening methods—screen-film mammography, digital mammography, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and biopsy—can identify breast cancer at earlier stages and facilitate early treatment.

The most widely used imaging technology for breast-cancer screening is mammography. Eight randomized trials evaluated the effectiveness of screening mammography in the United States (Shapiro, 1988; Shapiro et al., 1988), Sweden (Andersson and Janzon, 1997; Bjurstam et al., 2003; Frisell and Lidbrink, 1997; Nystrom et al., 2002; Tabar et al., 1995), Canada (Miller et al., 2000, 2002), and the United Kingdom (Alexander et al., 1999). Although criticisms of those trials have been published (Gotzsche and Olsen, 2000; Olsen and Gotzsche, 2001), independent review concluded that there was strong evidence of the effectiveness of mammography for women over 50 years old (Fletcher and Elmore, 2003; Health Council of the Netherlands, 2002; US Preventive Services Task Force, 2002; Vainio and Bianchini, 2002b). According to a meta-analysis that included all the trials, 15-year mortality from breast cancer in women 50–69 years old was decreased by 20–35%, and the reduction was statistically significant; it was reduced in women between 40–49 years old by about 20% (Fletcher and Elmore, 2003). Results of individual trials and another meta-analysis suggest statistically

significant reductions of 29–44% in the population 40–49 years old (Andersson and Janzon, 1997; Bjurstam et al., 2003; Hendrick et al., 1997). Some researchers have noted that screening mammography is associated with a high rate of false positives and overdiagnosis (that is, diagnosis of and treatment for some cancers that might not progress and cause morbidity or death) (Esserman et al., 2009). Such overdiagnosis results in patients being subjected to adverse effects of breast-cancer treatments and being labeled as having a “preexisting condition,” which can affect insurance coverage7 and raise emotional issues (Esserman et al., 2009). This points to the need to be able to differentiate between tumors that will progress and metastasize from those that will not. Recently, the US Preventive Services Task Force (2009) recommended “against routine screening mammography in women aged 40 to 49 years.” Instead, the task force said the decision to have mammography before the age of 50 years should be an individual choice and take into account individual risks and “the patient’s values regarding specific benefits and harms.” Those guidelines, however, are very controversial, “have had a polarizing effect in the breast-cancer community,” and have led to “confusion, fear, and anger on the part of patients with breast cancer, their families, and women’s health advocates” (Partridge and Winer, 2009). The communication of those guidelines is discussed further in Chapter 5.

The technology associated with mammography has improved substantially since the first studies of its efficacy. Major developments included more-sensitive high-resolution image intensifiers and film, low-absorption cassettes, and dedicated film processors, all of which contributed to radiation-dose reductions for women (Price and Butler, 1970). Changes in mammography tubes (for example, the use of molybdenum targets and filters with beryllium windows and smaller focal spots and the use of moving grids) improved image quality (Haus, 1990; Muntz and Logan, 1979).

Digital mammography was developed to overcome the limitations of screen-film mammography, such as difficulty visualizing low-contrast objects against dense backgrounds (Pisano and Yaffe, 2005; Shtern, 1992). Clinical trials (without death as an end point) have demonstrated that its diagnostic accuracy is equivalent to that of film mammography for the general population (Lewin et al., 2002; Pisano et al., 2005; Skaane et al., 2007; Vinnicombe et al., 2009), but that digital mammography has better accuracy than film in premenopausal and perimenopausal women, women who have dense breasts, and women less than 50 years old (Pisano et al., 2005). As of August 2010, 68.5% of accredited US mammography units were digital (FDA, 2010)—up from 36% in January 2008

(Karellas and Vedantham, 2008)—despite the high relative cost8 (Tosteson et al., 2008). Individualized screening strategies with such technologies as MRI and ultrasonography are being developed for women who are at high risk for breast cancer (Berg, 2009).

MRI provides three-dimensional images of the breast and outstanding soft-tissue contrast. Nine studies (Hagen et al., 2007; Hartman et al., 2004; Kriege et al., 2006; Kuhl et al., 2005; Leach et al., 2005; Lehman et al., 2005, 2007; Sardanelli et al., 2007; Warner et al., 2004) of women who were at very high risk for breast cancer collectively showed an increase in the detection of tumors by combining mammography and MRI for an overall sensitivity of 92.7% and greater detection of smaller, node-negative tumors (see Berg, 2009, for review; Kriege et al., 2004). Those results and others led the American Cancer Society to issue new guidelines for breast-cancer screening with MRI for women who have a 20% or greater lifetime risk of breast cancer9 (Saslow et al., 2007). Many women, however, cannot undergo MRI because of claustrophobia, obesity, renal insufficiency, or the presence of metallic implants (Berg, 2009). In addition, the false-positive MRI results that lead to unnecessary biopsy may limit its acceptability (Tillman et al., 2002).

Sonography is more available, better tolerated, and less expensive than is MRI as a supplemental tool to mammography (Berg, 2009). In high-risk women, mammography combined with sonography has a sensitivity of only 52% compared with 92.7% for mammography with MRI (Berg, 2009; Buchberger et al., 2000; Crystal et al., 2003; Gordon and Goldenberg, 1995; Hartman et al., 2004; Kaplan, 2001; Kelly et al., 2009; Kolb et al., 2002; Kuhl et al., 2005; Leconte et al., 2003; Lehman et al., 2005; Sardanelli et al., 2007; Warner et al., 2004). The supplemental breast-cancer detection rate of sonography in several studies has been consistently reported as 2.7–4.6 per 1,000 women screened (see Berg, 2009; Berg et al., 2008). Cancers found with screening sonography were almost always invasive and node-negative and had a median size of 9–11 mm (Buchberger et al., 2000; Corsetti et al., 2008; Crystal et al., 2003; Gordon and Goldenberg, 1995; Kaplan, 2001; Kolb et al., 2002; Leconte et al., 2003).

Newer technologies—such as tomosynthesis (Gur et al., 2009; Niklason et al., 1997; Poplack et al., 2007), digital subtraction mammography (Diekmann

et al., 2005; Dromain et al., 2006; Jong et al., 2003), dedicated breast computed tomography (Boone et al., 2001, 2006; Yang et al., 2007), positron-emission mammography (Berg et al., 2006), scintimammography (Khalkhali et al., 2000; Liberman et al., 2003), and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (Bartella et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2004; Meisamy et al., 2005)—have not yet been evaluated well enough in a screening setting to warrant their widespread adoption either adjunctively or as replacements for mammography.

It is important to note that all studies of screening with new technologies assess imaging end points, not mortality. The presupposition is that finding more cancers than are found with film mammography (at a less advanced stage) will lead to reduced mortality if implemented on a population-wide basis (Smith et al., 2004). As with other screening methods, there are adverse outcomes associated with false positives and overdiagnosis. In addition to stress and unnecessary biopsies conducted because of false positives, there is evidence that some breast tumors that would not progress to breast cancer are diagnosed as breast cancer through screening programs (Esserman et al., 2009).

Research Advances in Treatment

One of the earliest treatments for breast cancer, surgery with radical mastectomy and complete lymph-node removal, is disfiguring. A randomized clinical trial comparing 5-year survival after mastectomy, lumpectomy (tumor removal only), and lumpectomy with radiation showed that patients who underwent lumpectomy plus radiation had the same survival as those who underwent radical mastectomy (Komaki et al., 1990). Those results gave women options for breast cancer surgery.

Assessing breast-cancer metastases with sentinel lymph-node biopsy (SLNB) began in the middle 1990s, has replaced axillary lymph-node dissection (ALND) for determining the extent of spread of breast cancer, and has shown decreased posttreatment morbidity (Kell and Kerin, 2004; Lyman et al., 2005; Olson et al., 2008; Quan and McCready, 2009; Schrenk et al., 2000). A number of studies have demonstrated that SLNB is as accurate for staging breast cancer and is followed by similar short-term survival alone as in conjunction with ALND (Quan and McCready, 2009); large randomized controlled trials with longer followup are underway to evaluate SLNB further (Quan and McCready, 2009).

Surgery (lumpectomy or mastectomy) remains the primary treatment for breast cancer. Before and after surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy is an important component of breast-cancer treatment (NCI, 2009a). There has been development of many agents and combinations of agents and testing in clinical trials to assess survival and side effects in women who have breast cancer at different stages. The development of effective adjuvant therapies for early-stage breast cancer has greatly improved survival rates.

Several chemotherapeutic agents are available to treat patients with meta-

static breast cancer, resulting in substantial palliation and some survival benefits (Chia et al., 2007). More importantly, several trials have demonstrated that using chemotherapy to prevent recurrences in women with early-stage disease has had an enormous impact on mortality (Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group, 2005). Early trials were principally focused on cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and 5-flourouracil (Buzdar et al., 1988). Later studies demonstrated that the addition of the anthracyclines (doxorubicin and epirubicin) and the taxanes (paclitaxel and docetaxel) improve outcomes even further (Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group, 2005; Henderson et al., 2003; Martin et al., 2005).

As mentioned previously, therapies that interrupt the estrogen/ER pathway have been prime tools in treatment and prevention of breast cancer. Of these, the selective ER modulator (SERMs), tamoxifen, has been most influential in much of the decline in breast cancer mortality observed in the Western world over the last 25 years (Osborne, 1998). More recently, complete inhibition of estradiol synthesis in postmenopausal women has been affected by specific aromatase inhibitors (AIs), which are now known to be slightly more effective than tamoxifen in both the metastatic and adjuvant settings (Winer et al., 2005). Tamoxifen, and a similar SERM compound, raloxifene, have both been proven to prevent new ER-positive breast cancers in women at modestly high risk for the disease, and studies are underway to test the worth of AIs in this setting (Fisher et al., 1998; Vogel et al., 2006).

Trastuzumab is a monoclonal antibody that interferes with HER2 and has been shown to reduce mortality in both metastatic and adjuvant settings (Mariani et al., 2009). More recently, studies have demonstrated that a small molecular weight tyrosine kinase inhibitor, lapatinib, has activity in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer who have progressed on trastuzumab (Di Leo et al., 2008; Geyer et al., 2006). These two agents are now being compared, alone or in combination, in ongoing randomized adjuvant clinical trials.

Increased understanding of the genotypes and phenotypes of different breast cancers has allowed clinicians to individualize treatment in many ways. Studies in the 1970s and 1980s demonstrated that women with ER-positive breast cancer benefit from endocrine treatments, like tamoxifen and, therefore, those treatments should be used in those women (Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group, 2005). In contrast, patients with HER2-negative breast cancers appear to gain little, if any, benefit from trastuzumab or lapatinib (Press et al., 2008; Slamon and Pegram, 2001). More recently, gene or protein expression assays combining ER, HER2, markers of proliferation, and other factors, have been shown to identify women who might forego chemotherapy or for whom chemotherapy might not work (Albain et al., 2010; Fong et al., 2009; van’t Veer et al., 2005). More recently, studies of tumors that do not express either ER or HER2 have demonstrated that another pathway, the poly (adenosine diphosphate [ADP]–ribose) polymerase pathway, is involved in DNA repair and, therefore, in tumor survival

and in resistance to chemotherapy. In early trials inhibitors of this pathway have been reported to have antitumor activity, and large prospective randomized trials to determine their clinical utility are now underway (Fong et al., 2009).

Genetic research has also helped to move toward personalized medicine for women who have breast cancer. Women with low cytochrome P450 2D6 activity do not effectively metabolize tamoxifen to its active metabolite, and identification of those poor metabolizers helps assess the benefits of tamoxifen in individual breast-cancer patients (Desta et al., 2004; Kiyotani et al., 2010; Rooney et al., 2004). In additional, gene-expression profiles can identify women who will or will not benefit from the use of anthracyclines and other therapies, thus avoiding exposure of women who would not benefit from that toxic class of drugs.

More recently, other agents—such as AIs, which interfere with postmenopausal women’s ability to produce the estrogen—have been shown in large-scale clinical trials to be superior to tamoxifen in extending survival in women who have metastatic disease and in preventing recurrence when used as primary adjuvant therapy (Sparano et al., 2009). In addition, treatment with AIs after a full course of tamoxifen continues to improve recurrence-free survival compared with cessation of hormone therapy (Goss et al., 2003; Winer et al., 2005), and they are approved to treat postmenopausal women for breast cancer (Winer et al., 2005).

Another significant advance was discontinuing the use of an ineffective treatment. Before 2000, bone-marrow transplantation was commonly used in combination with high-dose chemotherapy despite the absence of a randomized controlled trial that demonstrated its efficacy. A randomized controlled trial showed that the combined treatment did not improve survival in women who had metastatic breast cancer (Stadtmauer et al., 2000; Weiss, 1999); the finding was confirmed in other studies (Farquhar et al., 2003). The use of bone-marrow transplantation was abandoned in the late 1990s (Welch and Mogielnicki, 2002).

Knowledge Gaps

Scientific research, spurred by demands by and involvement of breast-cancer survivors and advocates, has improved survival of women who receive a diagnosis of breast cancer (IOM, 2006). There are now about 2.5 million women with a history of breast cancer either living disease free or undergoing treatments (ACS, 2010a). Although research has demonstrated that generally these women recover and lead relatively normal lives, some of the survivors may suffer serious sequelae, such as persistent fatigue, cognitive changes, musculoskeletal aches and pains, sexual difficulties, and secondary malignancies. Sequelae arise from the toxicity of therapies, from the psychological and emotional aspects following treatment (for example, mastectomies), and from concerns over recurrence. Leading-edge research is now focused on understanding the biopsychosocial mechanisms that underlie these persistent problems, and new therapies are being developed to help in their management with a goal of improving the survivors’

lives (Bower, 2008; IOM, 2006, 2008; Miller et al., 2008). Despite those gains, more than 40,000 US women died in 2009 from breast cancer (see Table B-2). In addition, the gains against breast cancer have not been seen among all demographics groups, and the reasons for the higher mortality in black women needs to be better understood and addressed. The ability to differentiate between tumors that will progress and metastasize from those that will not is needed.

Lessons Learned

Breast cancer is an example of a serious disease for which the risks, and consequences have been decreased through advances in scientific research. Research has led to improved overall prevention, detection, survival of, and treatments for breast cancer, but there is a need to focus research programs on quality-of-life issues as well as mortality. If one looks at the overall progress made in the health of women who have breast cancer and at the research findings, the successes can not be attributed to a single aspect of the research but rather to multi-pronged research, including molecular, cellular, and animal experiments; improving diagnostic techniques; implementation of widespread screening programs; observational studies; and clinical trials. The disparities that remain highlight the need to focus research on groups that have the highest risks and burdens of disease. In addition, the increased risk of breast cancer from the use of hormone therapy (conjugated equine estrogen plus progestin) and the lack of efficacy of bone-marrow transplantation point to the need to conduct clinical research to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of treatments before widespread public use.

Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease—considered here as a group that includes heart disease and stroke—has seen major progress in women, as reflected in a decrease in mortality. Despite that progress and all that has been learned over the last 2 decades about cardiovascular disease in general, and about the potential differences in cardiovascular disease between women and men, in the United States cardiovascular disease is still the leading cause of death among women of almost all races and ethnicities,10 and it is a major contributor to morbidity and a decrease in quality of life in women (AHA, 2009).

|

10 |

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in white, black, and Hispanic women. It is the second-leading cause of death in Asian and Pacific Islander and in American Indian and Alaska Native women (see Appendix B). |

Incidence, Prevalence, and Mortality in Women

Cardiovascular disease in general used to be thought of more in relation to men than women, and most of the earlier cardiovascular research focused solely on men (AHRQ, 2009), which could be why some women underestimate their risk of cardiovascular disease and overstate their risk of breast cancer (Erblich et al., 2000). Statistics, however, show that cardiovascular disease has been the leading cause of mortality in US women since 1989 (see Appendix B). In 2006, one-third of US women had cardiovascular disease (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2009) and over 3 million women were discharged from short-stay hospitals with their first listed diagnosis as cardiovascular disease (AHA, 2009).

Since 1984, the non–age-adjusted number of deaths in women due to cardiovascular disease has exceeded the number in men; in 2005, nearly 0.5 million women died from cardiovascular disease—52.6% of all people who died from cardiovascular disease (AHA, 2009). Taking age into account, however, shows a different picture. The incidence is lower in women than in men in all age groups, and the prevalence is lower in women than men or the same in women as men between 20–79 years old, but higher in women 80 years old or older (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2009). Although cardiovascular disease in women remains a substantial problem, success can be seen in the recent decreases in mortality from cardiovascular disease. The age-adjusted rate fell by 48.9% in women (from 263.3 to 134.4 per 100,000) and by 50.8% in men (from 542.9 to 266.8 per 100,000) (Ford et al., 2007).

Cardiovascular disease can be classified as coronary heart disease,11 stroke, and non-ischemic heart disease (for example, mitral valve disease). Coronary heart disease and stroke are discussed here as examples of cardiovascular disease in women. The majority of cardiovascular disease in women is coronary heart disease, most of which is caused by atherosclerotic coronary disease or atherosclerosis. Coronary heart disease can manifest as angina (chest discomfort), ischemic heart disease (reduced blood supply to the heart) or acute myocardial infarction (heart attack). In 2006, about 8 million women in the United States were living with coronary heart disease (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2009). Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) indicate that the prevalence of acute myocardial infarction in women has increased over the last 2 decades but decreased in men (Towfighi et al., 2009). Of women 40 years old or older who have a recognized myocardial infarction, 23% die within a year compared with 18% of men (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2009). Younger, but not older, women have higher mortality during hospitalization after myocardial infarction than do men of the same age. The younger the patients, the higher is women’s mortality relative to men’s (Vaccarino et al., 1999).

Chronic coronary heart disease is a major contributor to heart failure in women. Almost 600,000 women are discharged from short-stay hospitals each year, and 2.5 million women are living with heart failure (AHA, 2009). The number of women living with chronic heart conditions is rising and is expected to continue doing so because of improved acute treatments for coronary heart disease, the aging of the population, and other advances in medical therapies.

Stroke, when considered separately from other cardiovascular conditions, is the third-leading cause of death among women, and about 4 million women survivors are estimated to be alive today (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2009). Each year, about 55,000 more women than men have strokes (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2009). Although it is attributable primarily to women’s longer life expectancy (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2009), more women have strokes even when compared with men in the same age group. One study analyzed NHANES data from 1999–2004 and found that self-reported stroke prevalence in women 45–54 years old was double that of men in the same age group (Towfighi et al., 2007).

Disparities Among Groups

With respect to cardiovascular disease as a group, 46.9% of black women 20 years old and older and 34.4% of white women had cardiovascular disease in 2006 (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2009).

Mortality from coronary heart disease was higher in black women than in white women (141 vs 110 per 100,000 age-adjusted population) in 2005. Black women in all age groups had a higher incidence of first heart attacks and overall heart attacks than white women. In 2006, the prevalence of coronary heart disease in women 20 years old or older was 6.9% in white women, 8.8% in black women, and 6.6% in Mexican American women (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2009).12

Data from 1998 indicate that the age-adjusted mortality rate from coronary heart disease and specifically from acute myocardial infarction is lower in Hispanic, Asian and Pacific Islander, and American Indian and Alaskan Native women than in either black or white women (CDC, 2001). Like mortality from most other cardiovascular diseases, mortality from stroke is substantially higher in black women than in white women (60.7 vs 44.0 per 100,000 age-adjusted population) (AHA, 2009). Low socioeconomic status is also related to higher mortality. Among women 60 years old or older with cardiovascular disease, those without a high school degree were twice as likely to die from their disease as were high school graduates (Lee et al., 2005). In one study that looked at age-adjusted death rates from cardiovascular disease in both black and white women, death rates are higher in those with less education and in those with less income (Pappas et al., 1993).

Research Advances in Knowledge of Biology

Research over the last 20 years has demonstrated that women have cardiovascular disease, and determining whether there are sex differences in cardiovascular disease and underlying biologic differences between women and men that could underlie the differences in disease is an active area of research (Rosenfeld, 2006; Shaw et al., 2009). A recent pooled analysis of data from 11 studies of acute coronary syndrome concluded that women have higher 30-day mortality; this may be largely explained by clinical differences on presentation (for example, women are older and have more comorbidities and risk factors than men) and differences in the severity of angiographically documented disease (Berger et al., 2009).

The Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study, sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, was conducted to evaluate diagnostic tests for heart disease in women and to determine whether evidence of myocardial ischemia occurs in the absence of obstructive coronary disease in women. Data from WISE highlight the role of microvascular dysfunction, subendocardial ischemia, inflammation, genetic predisposition, and neurohormonal imbalance in imparting risk in women (Bairey Merz et al., 2006; Quyyumi, 2006). Of the 7,603 women with symptoms screened, however, 936 (less than 5%) were enrolled in the study; women with a diagnosis of coronary artery disease on angiography and women with a previous coronary event (i.e., myocardial infarction, stroke, or revascularization) were excluded (Gulati et al., 2009). The WISE study only included females so sex-differences cannot be directly assessed. Differences in responses to ischemia are seen at the cellular level; different pathways trigger programmed cell death after ischemia in male and female rats and mice from birth (Bae and Zhang, 2005; Elsasser et al., 2000; Lang and McCullough, 2008; Vannucci et al., 2001). The clinical implications of those findings in humans and animals are unknown.

Research Advances in Prevention

Two-thirds of women who die suddenly from coronary heart disease had no previous symptoms (compared with half of men) (AHA, 2009). That suggests that primary prevention must be a key strategy to reduce the burden of coronary heart disease in women.

Smoking is the leading cause of cardiovascular disease, and the risk decreases quickly on smoking cessation. Hormone therapy (estrogen alone and estrogen plus progestin), as well as the selective estrogen-receptor modulators tamoxifen and raloxifene have been shown in a number of studies—the WHI, the Raloxifene Use for the Heart (RUTH) trial, and the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) trial—to increase the risk of stroke or fatal stroke in women (Nelson et al., 2009b; Stefanick, 2006; Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators, 2002). On the basis of the findings of the WHI, which was

designed to study the use of menopausal hormone therapy for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, menopausal hormone therapy is not recommended to prevent cardiovascular disease (Wassertheil-Smoller et al., 2003; Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators, 2002). Behavioral factors (for example, smoking, eating habits, physical activity) that affect the risk of cardiovascular disease are discussed in Chapter 2.

An important sex difference in the prevention of stroke is the use of aspirin. Aspirin has been shown to prevent ischemic strokes in women (primarily among those over age 65) but not in men (Bailey et al., 2010; Ridker et al., 2005). The risk of hemorraghic stroke and gastrointestinal bleeding, however, may be increased by aspirin use, and because women often have uncontrolled blood pressure and stroke as they age, stroke and bleeding are particularly important health issues for older women (Bailey et al., 2010; Ridker et al., 2005). National guidelines recommend that those risks be weighed against the benefits of aspirin, and that age be taken into account in decisions about aspirin chemoprevention (Mosca et al., 2007).

In an early clinical trial, statins (3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors) were shown to be effective in lowering cholesterol in a Scottish trial in men (Shepherd et al., 1995). The absence of women in that and other statin trials led to questions about extrapolating the data to women and thus a delay in their use in women, even those who had previously had a coronary event. A meta-analysis of data from those trials later demonstrated the efficacy of statins in women (LaRosa et al., 1999). A large-scale trial (JUPITER) showed that primary prevention benefits from statins are similar in women 60 years old or older and men 50 years old or older (Mora et al., 2010), however, the number needed to treat (that is, the number of patients who would have to be treated to prevent a single outcome event) and side effects might be higher in women than men (Ridker et al., 2009). A 2009 meta-analysis showed benefits of statin therapy in both women and men at risk for cardiovascular disease (Brugts et al., 2009), and a meta-analysis of trials (not specifically in women) comparing early statin therapy after acute coronary syndrome with placebo or usual care at 1 and 4 months following showed no reduction in deaths, myocardial infarction, or stroke with statin therapy (Briel et al., 2006). A prospective cohort study showed an increased risk of cataracts, kidney failure, and liver dysfunction in both men and women with statin treatment (Hippisley-Cox and Coupland, 2010). Further research is needed to define the risk–benefit ratio of statins for primary prevention in diverse populations of women with varying risks of cardiovascular disease.

Patient, physician, health-system, and societal factors can all contribute to gender and racial disparities in cardiovascular-disease outcomes, but their relative contribution is not known. In a survey of 500 physicians (300 primary care physicians, 100 obstetricians/gynecologists, and 100 cardiologists), primary care physicians were significantly more likely to place women, who according to their Framingham risk score were in an intermediate-risk category, in a lower risk category than they did for men (Mosca et al., 2005). That rating affected the

recommendations the physicians provided for lifestyle and preventive pharmacotherapy. Earlier studies also indicated that physicians may manage women’s chest pain less aggressively, particularly black women (Schulman et al., 1999). Gender-based disparities in cardiovascular care have been documented in commercial health plans and the greatest disparity is present among those who had recent acute cardiac events (Chou et al., 2007a,b).

The American Heart Association (AHA) reviewed what is known about the use and effectiveness of percutaneous coronary interventions and adjunctive pharmacotherapy in men and women and concluded that invasive percutaneous coronary interventions are “performed less frequently and with greater delays in women” (Lansky et al., 2005). Rates of reperfusion therapy are also lower in women than in men, and “there is no evidence that the gap has narrowed in recent years” (Vaccarino et al., 2005). Greater complications and early mortality have been detected in women as compared to men following revascularization (bypass surgery and percutaneous coronary interventions) and, therefore, the lower number of procedures might be beneficial to women (Kim et al., 2007).

Studies have shown a higher risk of death or acute myocardial infarction in women who have unstable angina and an increase in non–ST-segment myocardial infarctions in women after invasive treatment than in women after conservative treatment.13 A meta-analysis of eight trials indicated that invasive strategies benefit high-risk women—that is, those who have increased concentrations of the biomarkers creatine kinase MB or troponin—but do not benefit and possibly increase risk in women who do not have increased concentrations of those biomarkers (O’Donoghue et al., 2008). Similarly, invasive treatment has been shown to benefit high-risk women who have acute coronary syndrome, but study results indicate no benefits of and even harm after invasive treatment in non–high-risk women who have acute coronary syndrome (Lansky et al., 2005).

AHA published sex-specific evidence-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women in 2004 (Mosca et al., 2004), but the extent to which they have changed practice is not established. Most physicians are aware of the guidelines, but few state that they implement the guidelines (Mieres et al., 2005).

Research Advances in Diagnosis

Sex and gender differences in the presentation of cardiovascular disease have been studied over the last 2 decades, including studies looking for differences in clinical features (Canto et al., 2007; Correa-de-Araujo, 2006; Correa-de-Araujo and Clancy, 2006; DeCara, 2003; Dracup, 2007). The initial presentation of coronary heart disease is about 10 years later in women than in men (Mikhail, 2005). For myocardial infarction, the most common symptom for women is chest

pain, although myocardial infarction in women does occur in the absence of chest pain (AHA, 2010). Other symptoms of myocardial infarction include feeling out of breath; pain that runs along the neck, jaw, or upper back; nausea; vomiting or indigestion; unexplained sweating; sudden or overwhelming fatigue; and dizziness (AHA, 2010). Statistically, women who have myocardial infarctions are less likely than men to have coronary disease (Shaw et al., 2009). That chest pain is more common in men and is considered a “typical” symptom of heart disease may contribute to the finding that women are less likely to undergo diagnostic evaluation for symptoms and may have their conditions misdiagnosed (Brieger et al., 2004; Canto et al., 2007). Some evidence suggests that women and men experience cardiac pain differently, and that this affects the diagnosis of cardiovascular conditions and events (O’Keefe-McCarthy, 2008).

Women who have coronary heart disease are more likely to present with angina and fatigue, nausea and vomiting, and shortness of breath, whereas men are more likely to present with acute myocardial infarction or coronary heart disease death (DeCara, 2003). Women also have more atypical chest pain related to angina than men and more nausea, back pain, and jaw pain (Brieger et al., 2004; Canto et al., 2007; Kudenchuk et al., 1996; Milner et al., 1999).

Women and men vary in the predictive strength of risk factors, and this complicates the diagnosis of coronary arterial disease in women. Diabetes has been shown to be a stronger predictor of risk in women than in men (Scheidt-Nave et al., 1991). In a study of premenopausal women who underwent coronary angiography for suspected ischemia, diabetes was associated with hypothalamic hypoestrogenemia, increased prevalence and severity of angiographic coronary artery disease, and a slight increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (Ahmed et al., 2008). Isolated systolic hypertension is more common and more predictive in women than in men (Rich-Edwards et al., 1995), whereas a high concentration of low-density lipoproteins is more predictive of coronary arterial disease in men than in women (Rich-Edwards et al., 1995). An increase in triglycerides is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in women (Evangelista and McLaughlin, 2009).

C-reactive protein has been suggested for use as a risk marker, particularly in women (Cook et al., 2006; Ridker et al., 2003). Research on the clinical relevance of C-reactive protein is ongoing. The US Preventative Task Force concluded that although data are convincing that C-reactive protein is associated with coronary heart disease, evidence that its use as a risk marker improves risk estimates is weak, and evidence that reducing C-reactive protein levels protects against coronary heart disease is lacking for either women or men (Buckley et al., 2009).

Sex differences have sometimes been reported in the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic tests for cardiovascular disease. Kim and colleagues (2001) conducted a meta-analysis and found sex differences in the diagnostics. An AHA consensus statement in 2005 concluded that the present approach to diagnostic testing may require some variation when applied to women (Mieres et al., 2005). DeCara (2003) reviewed noninvasive cardiac testing in women and found a high

rate of false positives for coronary arterial disease with exercise electrocardiographic (ECG) stress testing in women (Hung et al., 1984; Mieres et al., 2005) and female-specific outcomes have been developed for exercise ECGs (Gulati et al., 2005). A systematic review for AHRQ, however, did not find sex differences in the accuracy of exercise myocardial perfusion imaging for diagnosis of coronary heart disease and found little difference in the accuracy of exercise myocardial perfusion imaging and exercise echocardiography for diagnosis of coronary heart disease in women (Grady et al., 2003).

Differences in the diagnosis of cardiovascular disease in women, if present, could bias the results of clinical trials. If trials are based on symptoms of coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease that are more commonly seen in men than in women, and female cases will be missed.

Research Advances in Treatment

Research laid the groundwork for a number of important pharmacologic breakthroughs in treating patients with cardiovascular disease. The use of beta-blockers and aspirin as soon as possible after a myocardial infarction quickly became the standard of care for men; however, women were not receiving that care and it took a few years for the use of beta-blockers and aspirin in women to approach that in men (Berger et al., 2009). The use of stents in women lagged behnd their use in men because the size of the stent was based on male blood vessels, which are typically larger than in women (Lansky et al., 2005).

As summarized by Lansky and colleagues (2005), the current use of stents does not appear to differ between the sexes. In addition, the mortality associated with their use is similar in women and men unless confounding risk factors are present in women (Chauhan et al., 2005; Mehilli et al., 2000).

Research has demonstrated that adjunctive pharmacotherapy is beneficial in women who are undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention as secondary prevention, including the use of aspirin, ADP–receptor antagonist antiplatelet agents (clopidogrel and ticlopidine), glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIa inhibitors, the antithrombin agents unfractionated heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin, and direct thrombin inhibitors (Antithrombotic Trialists Collaboration, 2002; Braunwald et al., 2002; Fernandes et al., 2002; Kong et al., 2002; Steinhubl et al., 1999; Stone et al., 2002; Wong et al., 2003; Yusuf et al., 2003). Because of women’s risk of bleeding complications at baseline (Lenderink et al., 2004), and because of risks of overdosing with GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors in women, care must be taken to avoid complications (Alexander et al., 2006).

Knowledge Gaps

Despite research advances in scientific knowledge related to diagnosis, risk factors, preventive interventions, and effective therapies for coronary heart disease in women, progress might have happened sooner if women had been better

represented in earlier studies of cardiovascular disease. More recently women have been enrolled in cardiovascular trials; however, a lack of knowledge about sex differences remains, in part because of a lack of sex-specific analysis and reporting of sex-specific results, with only 25% of trials of cardiovascular disease reporting on sex-specific results (Blauwet and Redberg, 2007; Blauwet et al., 2007; Grady et al., 2003). Because women have been consistently under-enrolled in cardiovascular-disease clinical trials (Grady et al., 2003; Kim and Menon, 2009; Sharpe, 2002), studies were not powered sufficiently to provide statistical significance on data for women, so meta-analyses have been used to determine whether the results obtained in men can be extrapolated to women (Grady et al., 2003). Because of their limitations, however, meta-analytic methods can not overcome a lack of enrollment or data on women, and they are not optimal for addressing the leading cause of mortality in women. A major limitation of evaluating data from eligible studies was that findings were often not stratified by sex, and little evidence was available to answer key questions about the disease in women (and in racial and ethnic minorities). Women continue to be inadequately represented in cardiovascular-disease clinical trials; this could be due in part to entry criteria that are based on symptoms seen more commonly in men (Grady et al., 2003). Cardiovascular disease may be a category in which sex-specific studies can be used to fill in the gaps (Lansky et al., 2005; O’Donoghue et al., 2008; Shaw et al., 2009).

Much also remains both to be learned about the biologic sex differences that underlie cardiovascular disease in men and to be done to use the information to develop sex-specific diagnostic, preventive, therapeutic, and rehabilitative approaches. Sex-specific diagnostic tools, especially for identifying subclinical disease, are needed as is a strategy for avoiding the delay in screening for, diagnosis of, and treatment of cardiovascular disease in women. Furthermore, the reasons for the disparities in mortality in different groups of women and how to address those disparities are also needed.

Although awareness of cardiovascular disease as the leading cause of death has nearly doubled among women since national educational programs, such as the Heart Truth and Red Dress campaigns, have been targeted to women—in 1997, only 30% of women recognized cardiovascular disease as the leading killer of women, significantly less than the 57% and 54% of women who recognized cardiovascular disease as the leading killer of women in 2006 and 2009, respectively (Mosca et al., 2010)—but awareness continues to lag among racial and ethnic minorities. Work is needed to raise awareness of the problem of cardiovascular diseases among women and their health-care providers, especially because awareness of cardiovascular-disease risk has been linked to the taking of preventive action (Christian et al., 2007; Mosca et al., 2006). Translation and communication issues are discussed in Chapter 5.

Lessons Learned

A major lesson was the recognition, not only by researchers but also by clinicians and the public, that cardiovascular disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in women. Part of the delay in recognizing that was lack of awareness, but other factors in the delay might be related to potential sex differences in the presentation (for example, age at presentation) of cardiovascular disease in women and men. That highlights the importance of recognizing the signs and symptoms of a disease in women, and ensuring that health practitioners and women are aware of those signs and symptoms. Sex-specific research on cardiovascular disease has shown potential sex-specific differences that affect everything from risk factors to diagnosis to treatment. Evidence indicates that behavioral factors are important for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (see Chapter 2 for a more detailed discussion), so research needs to go beyond the pathophysiology of the disease to the level of identifying effective interventions to modify people’s behaviors to prevent disease. Comorbidities with cardiovascular disease have also been seen and highlight the impact that comorbidities can have on diagnosis and treatment. Another major lesson is the importance of the translation of research findings into practice and policies to benefit all.

Cervical Cancer

The committee considered cervical cancer to be a disease where research findings have led to major advances in prevention and detection of the disease. There have been large decreases in incidence of and mortality from cervical cancer in the United States, mostly because of the use of the Papanicolaou (Pap) smear and the Bethesda rating system, both of which were developed before the period of our review. Cervical-cancer incidence and mortality continued to decrease during the last 20 years, and there are now improved treatment options for early-stage cervical cancer. Cervical-cancer research has also resulted in the development of a vaccine against human papilloma virus (HPV), an infectious agent that causes most cases of cervical cancer. The vaccine has the potential to protect women against cervical cancer, the leading cause of cancer death in women worldwide.

Incidence, Prevalence, and Mortality in Women

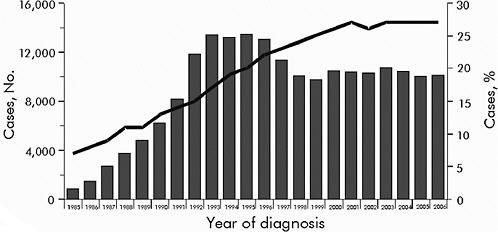

Cervical cancer was once one of the leading causes of cancer death in women in the United States, but its incidence and mortality in the United States decreased by about 74% from 1955 to 1992 and continues to decrease (ACS, 2009b). In the United States in 2010, it is estimated that 12,200 women will be diagnosed with cervical cancer, and 4,210 women will die from it (NCI, 2010c). The decreases in incidence and mortality are attributed mainly to regular cytology-based cervical-

cancer prevention programs, which were introduced in the United States in the 1960s (Wright, 2007; Zeferino and Derchain, 2006). In 2002–2007, the median age at diagnosis in the United States was 48 years; the median age at death was 57 years (NCI, 2010c).

Disparities Among Groups

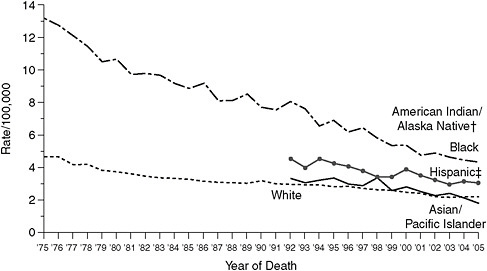

Cervical-cancer incidence and mortality decreased in the United States from 1996 to 2005 in all races and ethnicities on which there are surveillance data (see Figure 3-2) (NCI, 2008). Disparities among races and ethnicities persist despite those gains (Barnholtz-Sloan et al., 2009). The age-adjusted average incidence (cases per 100,000) in 2001–2005 was highest, at 13.7, in Hispanic women, followed by 10.8 in black women and about 8 in white and Asian and

FIGURE 3-2 Cervical-cancer mortality in 1975–2005 by race.

Mortality source: US Mortality Files, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Rates per 100,000 and age-adjusted to 2000 US standard population (19 age groups—Census P25-1130).

†Rates for American Indians and Alaska Natives not displayed, because fewer than 16 cases were reported for at least 1 year within interval.

‡Hispanics not mutually exclusive from whites, blacks, Asians and Pacific Islanders, and American Indians and Alaska Natives. Mortality data on Hispanics do not include cases from Connecticut, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Vermont.

SOURCE: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/statistics/race.htm (accessed May 5, 2010).

Pacific Islander women. In contrast, the average mortality (deaths per 100,000) in the same years was highest in black women at 4.7, followed by 3.2 in Hispanic women and 2.0 in white and Asian and Pacific Islander women. Possible reasons why advances are not translated to decreased mortality among all populations of women are discussed in Chapter 5. Incidence varies within racial and ethnic categories. For example, although overall Asian women are less likely to receive a diagnosis of cervical cancer than white women, within this subgroup Vietnamese American women are approximately 5 times more likely to be diagnosed with cervical cancer than white women (Taylor et al., 2004).

Research Advances in Knowledge of Biology

Epidemiologic, animal, and molecular studies have elucidated the role of HPV in cervical cancer and laid the groundwork for the novel diagnostic techniques and development of a vaccine discussed below and, ultimately, for the prevention of cervical cancer (Lehtinen and Paavonen, 2004; Olsson et al., 2009; zur Hausen, 2009).

The association between HPV type 16 and cervical cancer was found over 2 decades ago (Dürst et al., 1983, 1987). Research during the 1990s and early 2000s demonstrated that HPV is present in over 90% of premalignant cervical lesions and over 95% of cervical cancers and confirmed HPV as causal and necessary for cervical cancer (Bosch et al., 2002; Ferenczy and Franco, 2002; Franco et al., 2001; Muñoz, 2000; Muñoz et al., 2003; Walboomers et al., 1999). HPV 16 and 18 are responsible for cervical cancer (Schlecht et al., 2001; Woodman et al., 2007). Muñoz and colleagues (2003) demonstrated that HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 45, 52, and 58 account for 95% of squamous-cell carcinomas that are positive for HPV. Researchers also examined the structure of the virus particles; engineered proteins, called the L1 proteins, that reform to virus-like particles (or capsids); and demonstrated that the reformed L1 virus-like particles trigger an immune response in animals (Breitburd et al., 1995; Campo, 2002; Kirnbauer et al., 1992, 1993; Suzich et al., 1995; Zhou et al., 1991). The improved understanding of the relationship between HPV and cervical cancer laid the groundwork for the development of an HPV vaccine.

Research Advances in Prevention

It has been noted for centuries that cervical cancer is associated with sexual activity and sexual contacts (see Chapter 2 for discussion of sexual risk behavior) (zur Hausen, 2009), and limiting the number of sexual partners and using condoms have long been recommended for primary prevention of cervical cancer. Because sexual activity is a risk factor for cervical cancer, behaviors during teenage years and early adulthood can affect the risk of cervical cancer later in

life. There is recent evidence that condom use greatly reduces the risk of genital HPV infections (Winer et al., 2006).

The identification of the HPV virus as the causative agent in cervical cancer and the characterization of the virus and its components provided the basis of the development of a vaccine for the primary prevention of HPV infection and cervical cancer (Kulski et al., 1998). After trials to test safety (Harro et al., 2001) and antibody response (Carter et al., 2000; Petter et al., 2000), Koutsky and colleagues (2002) conducted a randomized controlled trial of an HPV 16 L1 virus-like particle vaccine in 2,392 women. A median of 17.4 months later, the vaccine had 100% efficacy in protecting against HPV 16 infection.14 Harper and colleagues (2004) conducted a randomized controlled trial of the efficacy of a bivalent HPV 16/18 virus-like particle vaccine against HPV 16 and HPV 18 infections in 1,113 women 15–25 years old. The vaccine was over 90% effective against incident and persistent infection with HPV 16/18. Relatively few minor and no serious adverse events were reported.

Gardasil®, a prophylactic vaccine containing the virus-like particle for HPV 6/11/16/18, has since been approved by FDA for girls and women 9–26 years old (FDA, 2008). Studies with the vaccine demonstrated safety; relatively few adverse events were reported. In one study the vaccine prevented 100% of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), adenocarcinoma in situ or cancer, and vaginal, vulvar, perineal, and perianal intraepithelial lesions associated with vaccine-type HPV in women with no evidence of previous HPV infection (Garland et al., 2007). When the vaccine was administered to subjects who had no evidence of previous exposure to either HPV 16 or 18, the prophylactic HPV vaccine was 98% effective in preventing HPV 16– and 18–related CIN 2/3 and adenocarcinoma in situ (FUTURE II Study Group, 2007). In women with evidence of HPV infection, regardless of the type of HPV infection, the vaccine reduced the incidence of vulvar, vaginal, and perianal lesions by 34% and of cervical lesions by 20% (Garland et al., 2007). The efficacy of the vaccine in preventing HPV 16– or 18–related CIN2/3 and adenocarcinoma in situ was lower (44%) in women who had been previously exposed to HPV types 6/11/16/18. The estimated efficacy of the vaccine against all high-grade cervical lesions regardless of the causal HPV type was 17% (FUTURE II Study Group, 2007). In October 2009 FDA approved Cervarix™ an additional accine to prevent cervical cancer and precancerous lesions caused by HPV types 16 and 18 (FDA, 2009a).

In October 2009 FDA approved one form of the vaccine in boys and men aged 9–26 for prevention of genital warts (HHS, 2009). The approval did not address the prevention of transmission of HPV to girls and women, and there has been much debate on whether boys and men should be vaccinated to decrease the prevalence of HPV in girls and women (Campos-Outcalt, 2009; Cuschieri, 2009; Hibbitts, 2009; Hull and Caplan, 2009).

Despite the evidence indicating safety and efficacy, a number of controversial issues have arisen around the implementation of HPV vaccination programs. Those issues are discussed in Chapter 5.

Although HPV infection is the major risk factor for cervical cancer, other risk factors have been studied. In general, diet does not appear to modify risks greatly. Diets rich in beta-carotene, or high in vegetables, however, have been linked to lower risk in a few studies (Hirose et al., 1998; La Vecchia et al., 1988), and antioxidants, such as carotenoids, have been shown to decrease HPV persistence in women (Giuliano et al., 1997, 2003). Smoking is associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer, although the extent to which the association is independent of HPV is not known (CDC, 2002a). Some research studies have shown an increased risk of cervical cancer associated with exposure to second-hand smoke (Tay and Tay, 2004; Trimble et al., 2005), but most reviews have concluded that there is inadequate or only suggestive evidence of an association (Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, 2005; Office of the Surgeon General, 2006).

Research Advances in Diagnosis